Contents

- Architecture of Prominent Sites

- Dhokeshwar Cave, Takli

- Ahmednagar Fort

- Bagh Rauza

- Farah Baksh Mahal

- Salabat Khan’s Tomb

- Vishal Ganpati Mandir

- Hume Memorial Church

- Shri Datta Mandir

- Residential Architecture

- A late 19th Century Residence at Shimpi Galli

- A 20th Century Residence at Khist Galli

- A Late-20th Century Residence at the Gulmohar Road of Savedi

- A Residential Building at Shrigonda Bypass

- Sources

AHILYANAGAR

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Ahilyanagar’s architecture reflects a layered history of religious, power, and cultural reinvention. Early sites like the Dhokeshwar Cave show how rock-cut forms shaped early medieval religious practice, while Nizam Shahi-era tombs, forts, and water palaces introduce Indo-Islamic styles tied to political control. Later Maratha and colonial structures, like the Vishal Ganpati Mandir and Hume Memorial Church, added new materials and forms, blending continuity with change. Across mandirs, palaces, and public spaces, Ahilyanagar’s built heritage reveals how belief and authority have continually reshaped its landscape.

Dhokeshwar Cave, Takli

The Takli Dhokeshwar Cave is a rock-cut Mandir carved into the hillside near Takli village, about 40 km from Ahilyanagar city. Believed to date back to the mid-7th century CE, the cave is located atop a hill, accessible by a long flight of stairs from Takli Dhokeshwar village along the Nagar-Kalyan road.

The Dhokeshwar Cave features a large hall with triple cells, measuring about 18.3 meters deep and 13.7 meters wide. The front façade includes two massive square pillars and two pilasters, supporting a large architrave that runs across the Mandir. Within this is the garbhagriha (sanctum), carved from a freestanding rectangular block of rock, surrounded by a dark circumambulatory passage. A square linga pitha, carved from the natural bedrock, sits at the center of the garbhagriha. The mandap (pillared hall) area includes two free-standing pillars, positioned parallel to the façade pillars. Dvarapalas are sculpted outside the garbhagriha in Abhanga pose.

![The garbhagriha houses a square linga pitha, surrounded by a dark circumambulatory path, with guardian Dvarapalas flanking its entrance.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/architecture/the-garbhagriha-houses-a-square-ling_IZb7VgV.png)

The cave walls display carved depictions of devtas and devis from the Pandavas’ era. These include Bhagwan Ganesh, Bhairav, Mahadev, Sahamata, Tandaveshwar, Ashtasiddhi, and others. A notable feature is the large Nandi murti, measuring about 10 ft long and 5 ft high, facing the garbhagriha.

Flanking the east-facing cave entrance are carvings of the river Devis, Yamuna to the south with Kurma beneath her, and Ganga to the north. Inside, a carving of the Saptamatrukas (seven mother Devis), flanked by Bhagwan Shiv-Virabhadra and Bhagwan Ganesh, adorns the south wall. The Dhokeshwar Caves reflect the technical skill of early medieval rock-cut architecture, with their spacious interior, detailed iconography, and experimentation with structural forms.

Ahmednagar Fort

The Ahmednagar Fort follows the architectural style of a Bhuikot fort, or ground fort, built on flat plains rather than a hilltop. The fort was constructed in 1490 CE by Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah, the founder of the Nizam Shahi dynasty, alongside the establishment of the city of Ahilyanagar. The Ahmednagar Fort is oval-shaped with a circumference of about 1.68 km, featuring 24 bastions and a large moat surrounding its stone walls. Originally built with mud, the fort was later strengthened with stone during the reign of Hussain Nizam Shah in the mid-16th century. Its defensive features included thick stone walls, a deep moat, and a drawbridge, making it one of the most well-planned and impregnable forts in Maharashtra.

![Ahmednagar Fort, an oval-shaped Bhuikot (ground) fort, features thick stone walls and 24 bastions.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/architecture/ahmednagar-fort-an-oval-shaped-bhuik_8qan7Hp.png)

Bagh Rauza

Bagh Rauza follows the Indo-Islamic architectural style, blending influences from late Bahmani and early Nizam Shahi styles. Located on the northeastern outskirts of Ahilyanagar, the mausoleum was built in the early 16th century as the resting place of Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I, founder of the Nizam Shahi dynasty and Ahilyanagar (previously Ahmednagar) city.

![Bagh Rauza is an Indo-Islamic tomb complex with a black basalt stone mausoleum featuring a white-plastered dome, enclosed within high boundary walls.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/architecture/bagh-rauza-is-an-indo-islamic-tomb-c_kfftiBQ.png)

Bagh Rauza is a square tomb complex enclosed by high boundary walls, with entrances on the north, east, and south sides. At the center stands the main mausoleum, raised on a high platform and constructed from black basalt stone. The building features a hemispherical dome made of brick and lime mortar, coated in white plaster. Inside the tomb, verses from the Quran are inscribed in gold lettering along the walls. The dome over Ahmad Nizam Shah’s shrine is the largest and most intricately detailed within the complex, reflecting Mughal and Persian stylistic influences.

Farah Baksh Mahal

Farah Baksh Mahal (also Farakh Baksh jalmahal) is a water palace designed in the Indo-Islamic architectural style, blending Persian and Deccan Sultanate influences. The palace was completed in 1583 by Salabat Khan II during the reign of the Nizam Shahi dynasty. Located along the Solapur road, the octagonal palace was built at the center of a now-dry quadrangular lake and once formed part of a larger palace-garden complex known as Farah Bagh.

![Farah Baksh Mahal is a two-storey Indo-Islamic water palace built from basalt stone, with thick lime plaster blending stone, pottery, and natural fibers.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/architecture/farah-baksh-mahal-is-a-two-storey-in_dCOkXEy.png)

Farah Baksh Mahal is a two-storey structure built primarily from locally quarried basalt stone, joined with lime mortar and finished with thick lime plaster containing stone, pottery, jute fiber, and dry paddy stem for strength and flexibility. The palace is elevated on a five-foot-high platform and features a central domed hall, surrounded by flat-roofed upper chambers and nine arched openings on each side to facilitate cross-ventilation. The structure once included a system of fountains inside and around the palace, integrated with a subterranean water channel. The interior has recessed wall niches, carved teakwood lintels, and remnants of stucco ornamentation, reflecting the functional yet refined features of the Nizam Shahi architectural style.

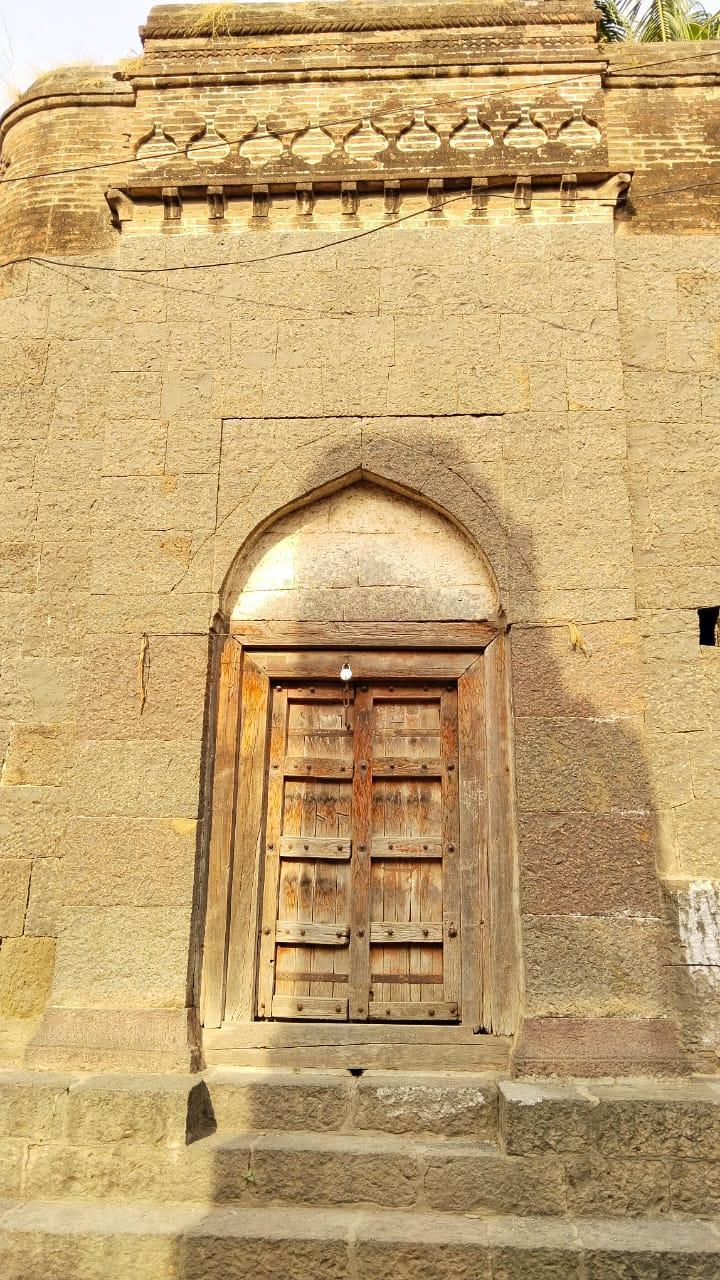

Salabat Khan’s Tomb

Salabat Khan’s Tomb, erroneously referred to as the Chand Bibi Mahal, follows the Indo-Islamic architectural style and is located atop the Shah Dongar plateau in Ahilyanagar. Built in the late 16th century, the tomb was commissioned for Salabat Khan II, the respected minister of Murtaza Nizam Shah I of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate.

![Salabat Khan’s Tomb is an octagonal, three-storeyed stone structure in the Indo-Islamic style.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/architecture/salabat-khans-tomb-is-an-octagonal-t_XllujWD.png)

Architecturally, the tomb is simple, with minimal ornamentation. It is an octagonal, three-storeyed stone structure, measuring approximately 939m above sea level. Each storey is surrounded by verandahs with large casement openings, allowing light and air to enter from all directions. A popular local belief claims that the tomb was originally intended to be eight storeys tall, allowing one to see Delhi or Daulatabad from its highest point. However, only three storeys were completed.

Vishal Ganpati Mandir

The Vishal Ganpati Mandir follows the traditional Maratha architectural style, characterized by its ornate yet sturdy design. Located in the Maliwada area of Ahilyanagar, the Mandir is estimated to be around 400 to 450 years old and is locally regarded as the gram devta of the district. Originally constructed from wood, the current structure was later rebuilt using Makrana marble (a type of marble notably used to build the Taj Mahal), lending it a striking white appearance.

The Vishal Ganpati Mandir stands approximately 70 feet tall, with its prominent shikhara and kalash visible from surrounding neighborhoods. The Mandir’s exterior features decorative arched windows (jharokhas), finely carved stone panels, and a domed shikhara typical of Maratha mandir architecture.

Hume Memorial Church

The Hume Memorial Church draws inspiration from Gothic Revival architecture. This Presbyterian church was constructed between 1902 and 1906 in the Khisti Galli area of Ahilyanagar and was named after Rev. Dr. Robert Allen Hume, one of the first American missionaries to settle in the region.

The Hume Memorial Church is built using locally sourced stone and features a pitched roof supported by a wooden truss system. The church’s stained-glass windows, designed with lotus flower motifs, introduce soft colored light into the space and are representative of European Gothic cathedrals. The interior showcases extensive use of teak (Sangwan) wood in the pews, balconies, and ceiling, reflecting skilled timber craftsmanship.

Shri Datta Mandir

Shri Datta Mandir follows the architectural style of a modern Navaratna mandir, blending traditional Indian mandir design with contemporary construction methods. The Mandir, located near Premdan Chowk in Savedi, was constructed in the early 21s century and is believed to be one of the largest Datta mandirs in India. Built entirely from Gulabi Bansi Paharpur Dagad (pink Rajasthani stone), the structure stands as a significant architectural landmark in the city.

Shri Datta Mandir is notable for its use of pink sandstone and the absence of iron in its construction. The Mandir measures approximately 160 ft. in length, 90 ft. in width, and rises to a height of 90 ft. A team of Rajasthani artisans crafted the intricate stone carvings that adorn the temple walls. Along the sides of the staircase leading to the main sanctum, sculptural panels depict Bhagwan Krishna lifting Mount Govardhan and Bhagwan Hanuman with the Vanar Sena building the stone bridge to Lanka, adding rich narrative elements to the Mandir's design.

Residential Architecture

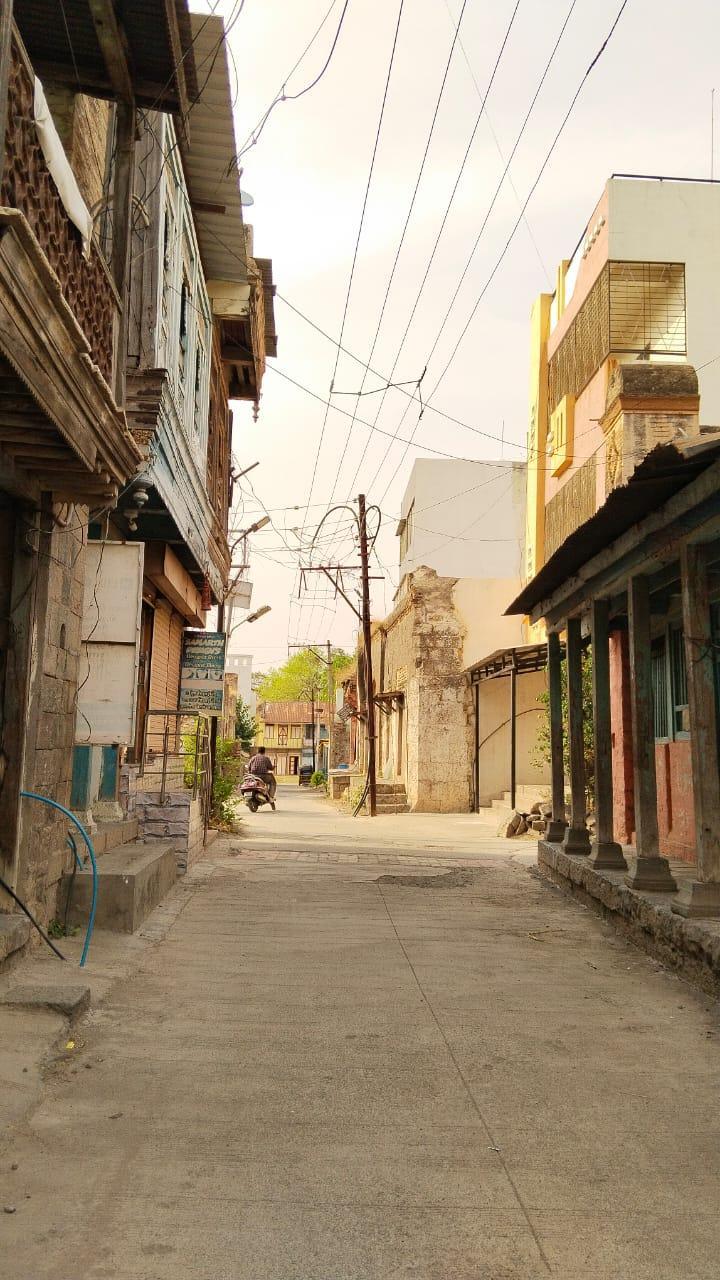

A late 19th Century Residence at Shimpi Galli

Shimpi Galli is a narrow lane situated in the Shrigonda taluka of Ahilyanagar. This area contains a settlement that according to local accounts was formed in the 1880s. Notably, there are many old residential structures which can be found within this galli. Among these structures stands a two-storey residence believed to have been built in 1882.

The architectural character and design of this residence is very distinctive. The composite structure (a technical term used to describe the materials that make up the house) of the house consists of both stone and brick. The ground floor is constructed from black basalt stone blocks, while the upper floor consists of exposed brick.

The architectural details and elements of the residence are striking. The doors are constructed from wooden planks arranged in panel patterns. The main entrance features a distinctive turmeric yellow color scheme and includes a small niche above the doorway. The small niche, notably, is tied to a cultural belief. It is traditionally used for placing devis and devtas that the home’s inhabitants revere as their guardian deities. The interior doors are around 5 ft. in height.

The windows feature iron rods arranged horizontally in a style regionally known as “Gajachya khidkya.” Each window is divided into two sections, an upper portion for ventilation and lower panes that open inward to allow light entry. The windows are relatively small due to the stone construction and load-bearing design. Set within niches with rounded tops (a characteristic element which can be found in Maharashtra) these windows are accentuated with contrasting colors.

The external railings are a distinctive architectural feature of the residence. These decorative elements extend around the residence’s perimeter with a cornice displaying geometric and floral motifs. The railings consist of metal square pipes arranged horizontally, supported by a wooden cornice. Interior railings incorporate precast iron panels painted white, supported by wooden columns, with a half-round wooden top rail finished in blue.

The residence includes an internal courtyard with wooden rafters supporting a metal sheet covering, which was most likely added later. The interior walls contain wooden columns that provide structural support, with rafters holding the roofing planks.

The ground floor ceiling consists of wooden members covered with planks that serve as the floor for the upper level. Throughout the house, there are various spaces that reveal the contrast between original construction and subsequent additions. Still today, the house stands as a remnant of the architectural styles that were once commonly found across the district.

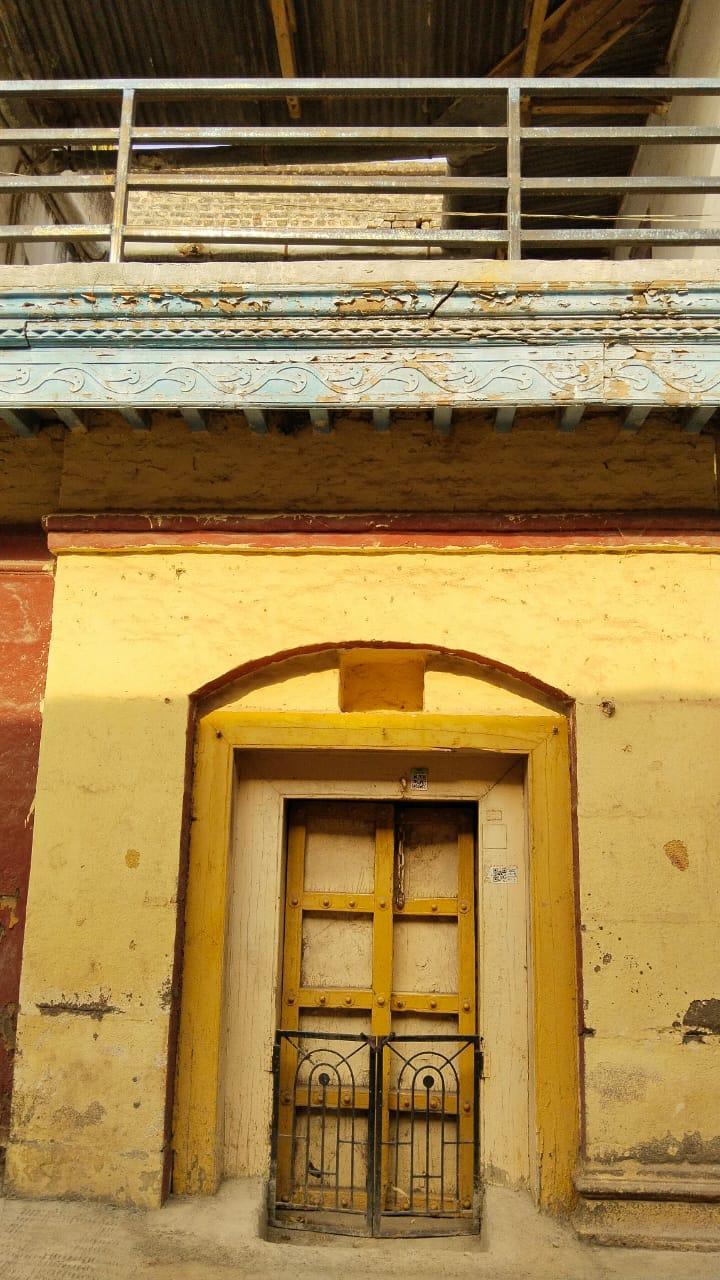

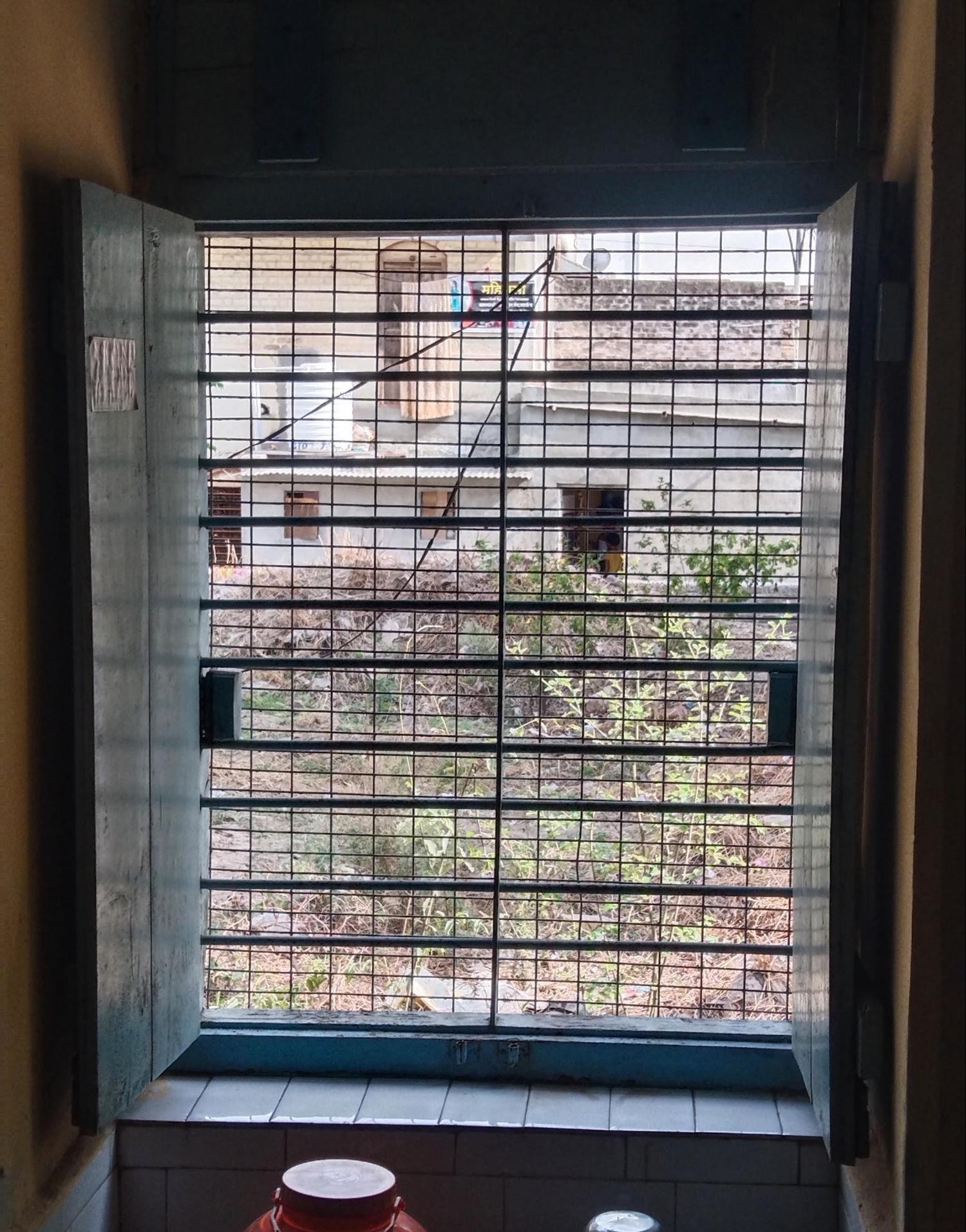

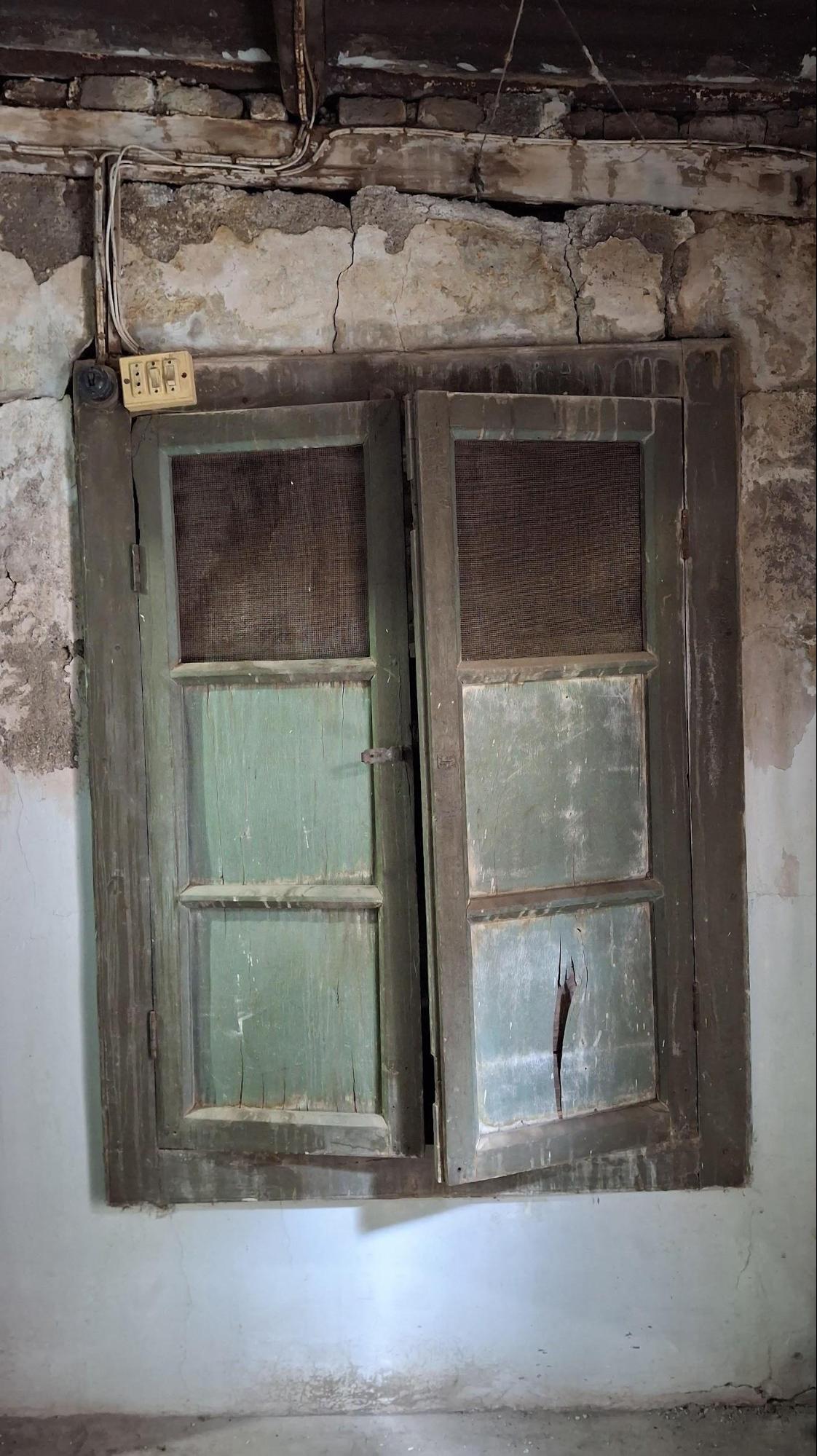

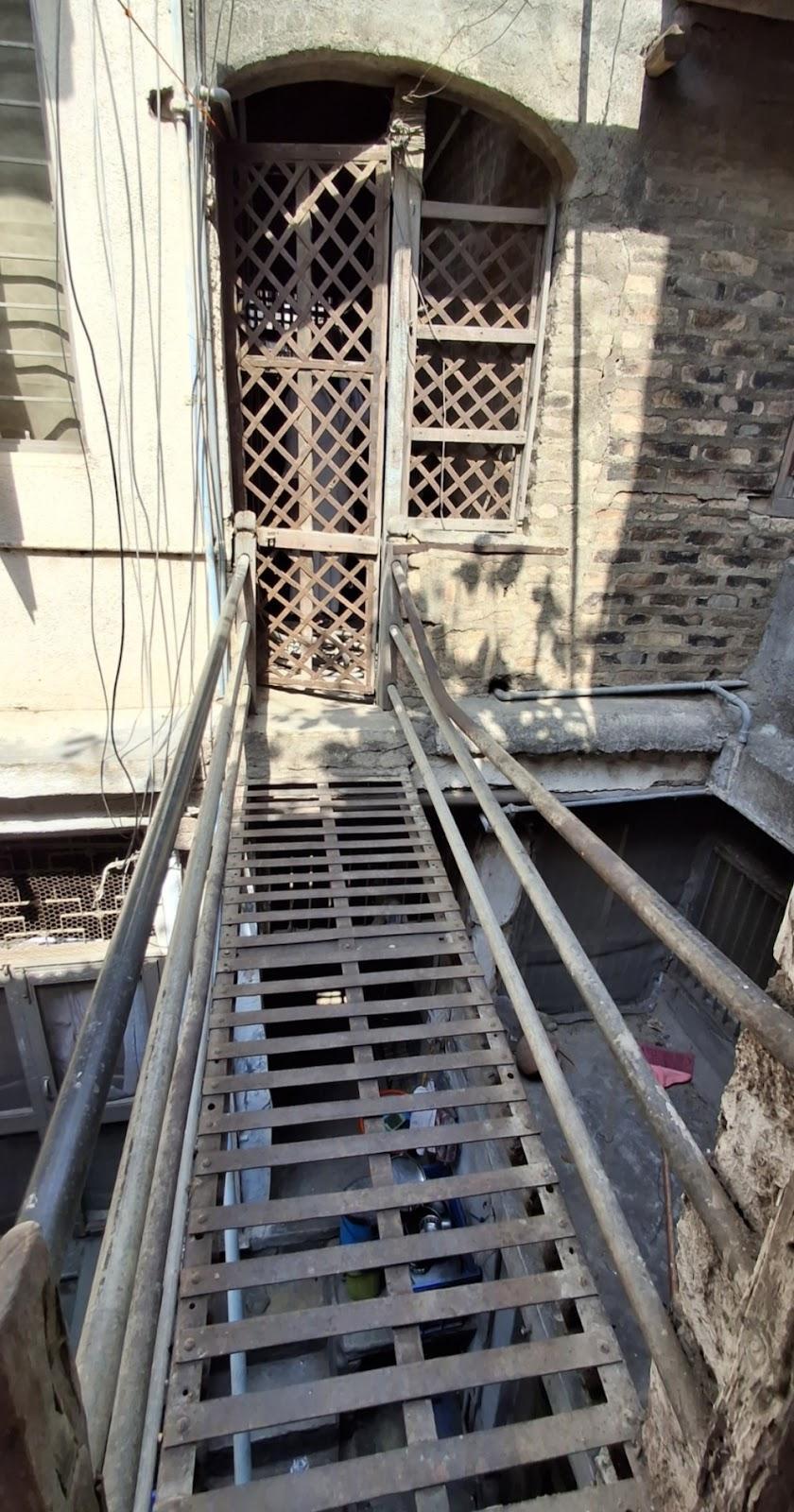

A 20th Century Residence at Khist Galli

Khist Galli is a residential area within Ahilyanagar City. The locality is approximately 100 years old, with the Maliwada Mandir serving as a notable landmark. Within this area stands a one-storey residential structure, estimated to have been built in 1931, which strikingly has a very distinct architectural character.

This residence is part of a cluster of older homes in the galli. These structures, designed in a historical architectural style, offer a striking contrast to the new concrete buildings that now define much of the locality’s street character. Yet, in this quiet juxtaposition, they offer a rare, and increasingly important, insight into the architectural heritage of the locality.

The residential building features a plinth (a technical term used for the base of the structure) constructed of random course stone masonry finished with plaster and paint. The composite structure is primarily made up of brick which is both plastered and painted. The house stands approximately 2.5 times the human height.

The house has two entrances, with the front door positioned at the center of the facade on an elevated surface.

The main entrance sits on a small plinth with central steps, known locally as ‘payrya.’ The entrance features two doors, an iron safety door and a wooden paneled door with decorative carvings. The doors of the house each have a very distinct design.

Many doors at the back entrance of the house are wooden and painted in pink and cream white. The main door includes ring knockers on both panels and is flanked by two foldable wooden ledges used as ‘devli’s’ for placing oil lamps during festivals.

The doors utilize a traditional chain (‘Kadi’) locking system. The wooden panel doors are approximately 6 ft. tall.

The windows of the home feature iron grills set in wooden frames, with solid wood panel panes. The front-facing windows have devli’s on both sides for festival lighting. The windows are set within niches topped with curved arches and stone embellishments.

Some windows have mosquito mesh in their upper sections for ventilation. The ground floor includes small clerestory windows for air circulation.

The exterior railings of the residential structure consist of cast iron panels within wooden frameworks, while the interior courtyard railings are simpler metal rods in wooden frames. Both maintain a rustic finish. The interior railings include a top wooden section with square openings for ventilation.

The roof is supported by a wooden framework covered with metal sheets and Mangalore tiles.

As mentioned above, this house has a very distinctive architectural character. Perhaps this is because there are several notable elements within it that reveal a pattern of regional design practices and contribute to both its structural and cultural significance. One such feature is a small, old iron bridge on the first floor.

Another fascinating element which can be found in the house is an underground passage, locally referred to as “Balad.” According to residents, these tunnels were once common in homes across Khist Galli and were originally built as hidden refuge spaces during times of conflict. Though now sealed, they remain an important part of the area’s architectural history.

A Late-20th Century Residence at the Gulmohar Road of Savedi

Gulmohar Road in Savedi is a locality where residential spaces began to develop extensively in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. During this period, a housing society called the Mangal Housing Society was formed which featured a cluster of similar-looking residences. Among these residences, Devashish stands as a notable bungalow, constructed in 1993. Remarkably, it is said to be the first bungalow of the Mangal Housing Society.

As the first house in the housing society, Devashish plays a defining role in the layout of the area. The arrangement of homes follows a structured pattern, with this bungalow positioned at the entrance of the housing society.

One can find several distinct architectural features within the bungalow, which align very much with contemporary architectural trends and practices. Balusters (short, vertical decorative columns) are prominently used in the balcony railing, terrace parapet, and external enclosure wall, adding a decorative yet functional element to the design. The exterior also features a contrasting paint scheme and a curved structural form, making it visually striking.

All doors in the bungalow are uniformly crafted from teak wood, featuring decorative brass handles and traditional ‘Kadi’ locking systems. For added security, the main entrance is reinforced with an external mild steel grill door. While the main door has a polished finish, the interior doors have painted finishes that match the overall design.

The windows throughout the residence maintain a consistent design, featuring geometric patterned iron grills mounted externally. Each window is framed with teak (Sagwan) wood and fitted with glass panels.

The residence features two landscaped garden areas, one situated adjacent to the main entrance and another in the rear yard.

Various contemporary landscape design elements can be found throughout the residence. There are exposed concrete slabs that define the walkways of the residence and interlocking tiles in yellow which can be seen at the garden which lies at the entrance. In the backyard garden, an arrangement of flower pots suggests the homeowner’s keen interest in horticulture, adding a personalized touch to the green space.

A Residential Building at Shrigonda Bypass

As time passes, one can usually see how new architectural styles gradually begin to reshape the region’s landscape. In Shrigonda Bypass, a locality often described as a “developing area,” this transition is evident. Over the 21st century, mid-rise buildings have increasingly become part of the locality’s built environment (a technical term for the human-made surroundings that make up a community). Among them is a four-storey residential apartment building, whose construction was completed in 2019.

The building’s design significantly differs from older homes of the district. It features a larger scale and a relatively more contemporary architectural approach which can typically be seen across many semi-urban and urban regions of Maharashtra.

The composite structure of the building very much aligns with the mainstream practices of the current day. It uses reinforced cement concrete (RCC) with steel and cement for the main framework. Its walls are made of brick, while the floors have steel frameworks filled with concrete and covered with tiles.

The main entrance has a mild steel grill door outside the porch area. The inside doors are flush doors with veneer and polish.

The windows have mild steel grills with a simple pattern which is called the “Bombay design.” The windows slide open and have aluminum frames with glass panels.

Metal and glass are materials that have been commonly used in the windows and railings of the home. All of the features, all in all, showcase how the ‘residential spaces’ of this era have been reimagined so differently from the houses of the 19th and 20th century.

Sources

Government of India. Ahmednagar: Ahmednagar Fort. Maharashtra Tourism. https://maharashtratourism.gov.in/fort/ahmed…

M Singh and S Vinodh Kumar. 2019. Architechtural features and characterization of 16th century Indian Monument Farah Bagh, Ahmed Nagar, India. International Journal of Architectural Heritage. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332…

Shree Datta Devasthan Trust. Shree Datta Kshetra. Shree Datta Devasthan Trust. https://dattadevasthan.org/shree-datta-kshet…

Tour My India. Bagh Rauza Ahmednagar. Tour My India. https://www.tourmyindia.com/states/maharasht…

Tour My India. Salabat Khan Tomb Ahmednagar. Tour My India. https://www.tourmyindia.com/states/maharasht…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.