AHILYANAGAR

Language

Last updated on 18 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Language has played a crucial role in shaping India’s social and political landscape, with pivotal moments such as the States Reorganization Act of 1956, which redrew the country’s states along linguistic lines. Ahilyanagar, formerly part of the Bombay Presidency, became part of Maharashtra in 1960 when Bombay State was divided to form Maharashtra and Gujarat. As a result, Marathi is the most widely spoken language in the district. The Marathi spoken in Ahilyanagar, however, carries regional characteristics, a distinct vocabulary, subtle pronunciation differences, and a distinct tone that, in many ways, makes it unique.

The district is also home to multiple speech communities (a group of people who use and understand the same language or dialect), who each maintain their own distinct linguistic traditions. Some of the lesser-known languages spoken include Thakaree, Bhilli, and Kolhati. In addition to its linguistic diversity, the district has safeguarded a variety of historical scripts, which are displayed in a local museum. This museum offers a glimpse into the region’s long history of languages through writing, showcasing scripts that have been in use for centuries.

Linguistic Landscape of the District

At the time of the 2011 Census of India, several languages were spoken as mother tongues in Ahilyanagar district. According to the 2011 Census, Ahilyanagar district had a total population of approximately 45,43,159. Of this population, 88.89% reported Marathi as their first language. Hindi followed at 4.79%, while Urdu and Marwari accounted for 2.74% and 0.82%, respectively. Smaller linguistic communities included Telugu (0.75%), Vadari (0.49%), Gujarati (0.25%), Punjabi (0.17%), Bhili/Bhilodi (0.15%), Sindhi (0.14%), Banjari (0.14%), Lamani/Lambadi (0.10%), Kannada (0.05%), and Paradhi (0.05%).

Language Varieties in the District

Nagari Marathi

Nagari Marathi, also often referred to as गावाकडची (Gavakadchi) or रानाची (Ranachi) Marathi is an informal variety of Marathi that is commonly spoken by the residents of Ahilyanagar district. This form of Marathi is distinct due to its unique vocabulary, pronunciation, and expressions, making it different from the Marathi from other variations of the language.

Nagari Marathi includes several words that differ from those commonly used elsewhere. These words reflect the conversational and colloquial nature of this variety.

|

Nagari Marathi Word |

Nagari Marathi Phonetic Transcription |

Marathi Equivalent |

Marathi Phonetic Transcription

|

Meaning |

|

पोरगा (Porga) |

/ˈpoːɾɡa/ |

मुलगा (Mulga) |

/ˈmʊlɡa/ |

Boy |

|

पोरगी (Porgi) |

/ˈpoːɾɡi/ |

मुलगी (Mulgi) |

/ˈmʊlɡi/ |

Girl |

|

लई (Lai) |

/ˈləɪ/ |

खूप (Khup) |

/kʰuːp/ |

Much |

|

व्हय की (Vhay ki) |

/'ʋʰəjə kɪ/ |

हो (Ho) |

/hoː/ |

Yes |

|

भेटला (Bhetla) |

/ˈbʱɛʈla/ |

मिळाला |

/'mɪɭaːla/

|

Met (used for things) |

As one can see above, in Nagari Marathi, the word “लई (Lai” often replaces “खूप (Khup).” Speakers might often use the word in sentences like “माझा लई डोका दुखू राहिला” (Mājhā lai ḍokā dukhū rāhilā) which means that “My head is hurting a lot.” The substitution of “खूप (Khup)” in Nagari Marathi represents what linguists might term a regional lexical preference, where other variants of a word are preferred to be used. This variation, notably, is what locals say sets Nagari Marathi apart from other forms of Marathi, such as Puneri Marathi, where “खूप (Khup)” usually remains the preferred term in both formal and informal contexts.

Nagari Marathi features unique expressions that are uncommon in other forms of Marathi. These phrases act as cultural markers, reflecting the informal and expressive nature of speech in the region.

- “अय्य भो” (Ayy bho) – An exclamation, often used for emphasis.

- “काय राव” (Kay rao) – An informal way of saying “Why?” or “What?”, similar to “Why, dude?”.

- “विषय का भो” (Vishay ka bho) – “What is the matter?,” used casually.

A speaker might say, “अय्य भो, पूर्वा, असं का वागतीयेस तू?” (Ayy bho, Prakash, asa kā vāgtiyes tū?), which translates to “Hey Purwa, why are you acting like this?”. Similarly, "काय राव, असं कसं?" (Kay rao, asa kasā?) is used in a way similar to “Why, dude? How come?”.

These expressions are rarely heard in regions like Pune, where Marathi tends to follow a more formal structure, giving the variety its own distinct identity.

Thakaree

Thakaree is a language spoken by the Thakar community, who live in various regions across Maharashtra, including Ahilyanagar district. Like many communities, the Thakars have different subgroups spread across different areas. Each subgroup has developed slight variations in how they speak, different pronunciations, words, or grammar patterns, influenced by where they live and who they interact with.

There has been much discussion about the origins of Thakaree. Mohan Ransingh, in Languages of Maharashtra (2017), notes that scholars suggest Thakaree and Marathi both likely developed from an older language called Apabhramsha Prakrit. This shared ancestry is why they are said to have so many similarities. Govind Gare (2002) notes that the way Thakaree speakers pronounce words shares patterns similar with Marathi pronunciation.

Aspiration Sounds

One of the most distinctive features of Thakaree is how it handles certain sounds. Many Indian languages, including Marathi, have what linguists call “aspirated” sounds—consonants pronounced with a small puff of air. This puff of air can be felt if one places their hand in front of their mouth while saying the English word “pin” (which has the puff) compared to “spin” (which doesn't).

In Marathi, several letters have this breathy quality (written as /ʰ/ by linguists), including भ (bh), थ (th), ध (dh), फ (ph), and ह (h). Thakaree, however, tends to drop this breathiness in pronunciation.

|

Marathi |

Thakaree |

Meaning |

|

आम्ही (ãːmʰi) |

आमी (ãːmi) |

we |

|

तुम्ही (tumʰi) |

तुमी (tumi) |

you |

This pattern—removing the breathy quality from consonants—is a major way that Thakaree developed its own sound.

Demonstrative Pronouns

Thakaree also simplifies some of the words used for pointing things out:

|

Marathi |

Thakaree |

Meaning in English |

|

हे (he) |

ये (je) |

"this" |

|

ते (te) |

ये (je) |

"that" |

Where Marathi uses different words for "this" and "that," Thakaree uses the same word for both, which creates a simpler system.

Other than these similarities, Thakaree also has its own distinct vocabulary. Interestingly, Mohan Ransingh notes that in Thakaree, there is no separate verb for “to drink.” Instead, speakers say phrases like “eats water” or "eats wine" instead of “drinks water” or “drinks wine.” Thakaree also contains unique words that reflect the culture and daily life of speakers:

|

Thakaree |

English Transliteration |

Phonetic Transcription |

Meaning in English |

|

कामरून |

kamrun |

Kamrun |

blankets |

|

गुळमी |

gulmi |

guɭmi: |

bowl |

|

माल्टी |

malti |

malʈi: |

earthen bowl |

|

Thakaree |

English Transliteration |

Phonetic Transcription |

Meaning in English |

|

मावा |

mava |

maʋa |

father-in-law |

|

भैन |

bhen |

bʰɘin |

sister |

|

आये |

aaye |

aːje |

Mother |

Kolhati

The Kolhati language is spoken by the Kolhati community, a group historically associated with performance arts such as acting, dancing, singing, and gymnastics. Their language, like their traditions, has evolved through generations, reflecting both their unique cultural identity and social history.

There is a very interesting legend which is tied to the origins of this community. According to this story, when Bhagwan Shiv narrated the origins of mankind to Devi Parvati, he described eighty-four different yonis (species) on Earth, with humans being one of them. Curious about the origins of different castes, Parvati inquired further, to which Shiva explained that every caste descended from a rishi. One particular verse, “Kumbhak Rushi prasidha jagati, Kolhati garbhaj,” (transliterated as ‘Kumbhak Rishi is renowned in the world; the Kolhati community is born from him) he says suggests that Kumbhak Rishi is regarded as the progenitor of the Kolhati community. This legend is one of the reasons why many perceive the Kolhatis to be an ancient community. This perception, in many ways, adds to the richness and history of their linguistic traditions.

The Kolhati community is spread across various regions of Maharashtra. According to Arun Gajanan Musle in Languages of Maharashtra (2017), Kolhati speakers can be found in districts such as Ahilyanagar, with notable settlements in Ahilyanagar city, Jamkhed, Shrigonda, Parner, Akole, Shrirampur, and Sangamner.

Every language evolves uniquely, influenced by its speakers’ history, environment, and social interactions. The Kolhati language, like many others, has a vocabulary enriched by indigenous words as well as borrowings from surrounding languages.

The vocabulary of the Kolhati language reflects the community’s unique cultural and linguistic identity. Kinship terms, or words used to describe family relationships, vary widely across languages and cultures. In Kolhati, these terms carry distinct phonetic features and reflect cultural nuances in how family relationships are expressed.

|

Kolhati |

English Transliteration |

Phonetic Transcription |

English Meaning |

|

फप्फी |

Phaphphi |

/pʰəppʰi:/ |

Aunt |

|

माव |

Mav |

/mav/ |

Mother |

|

बप |

baeep |

/bɘp/ |

Father |

They demonstrate the phonetic distinctiveness of Kolhati, particularly through aspirated consonants like /pʰ/ and vowel variations, which shape the rhythm and articulation of the language.

The way seasons are named in Kolhati offers insight into the community’s deep-rooted connection with nature.These seasonal terms, while distinct, exhibit similarities to those in Marathi and Hindi. This suggests a process linguists refer to as ‘borrowing’, which occurs when one language adopts words or structures from another.

|

Kolhati |

English Transliteration |

Phonetic Transcription |

English Meaning |

|

घम |

Gham |

/gʰəm/ |

Summer |

|

पाणी के दिन |

Paani ke Din |

/paɳiː ke di̪n/ |

Monsoon |

|

थंड |

Thand |

/tʰɘ̃d/ |

Winter |

The phrase "पाणी के दिन" (Paani ke Din) literally translates to “Days of Water,” capturing the essence of the monsoon season in a way that is unique to Kolhati culture. This construction is likely influenced by Hindi, yet it reflects how Kolhati speakers conceptualize and express their environmental cycles. Such expressions, in many ways, reveal how language preserves cultural perspectives and unique ways of understanding the world through words.

Ancient Scripts & Writings

Language is not only preserved through speech but also through writing, which has played a crucial role in documenting and transmitting knowledge across generations. As noted in Languages of Maharashtra (2017), “The invention of linguistic scripts is one of the most important developments in human civilization. These scripts have helped humanity establish, develop, and refine culture while facilitating the compilation and continuous expansion of knowledge.”

Writing serves as more than just a tool for recording speech; it has become a repository of cultural memory and history through different eras. Many scripts have been used by different dynasties over time, revealing stories of migration, conquests, and linguistic traditions. The presence of multiple scripts in a single region reflects the layers of migration, administration, and cultural synthesis. Interestingly, variations exist not only in the scripts themselves but also in the forms and materials used for writing. In Ahilyanagar district, the Ahmednagar Historical Museum houses a wealth of inscriptions and documents, offering a glimpse into Ahilyanagar’s history through its written records.

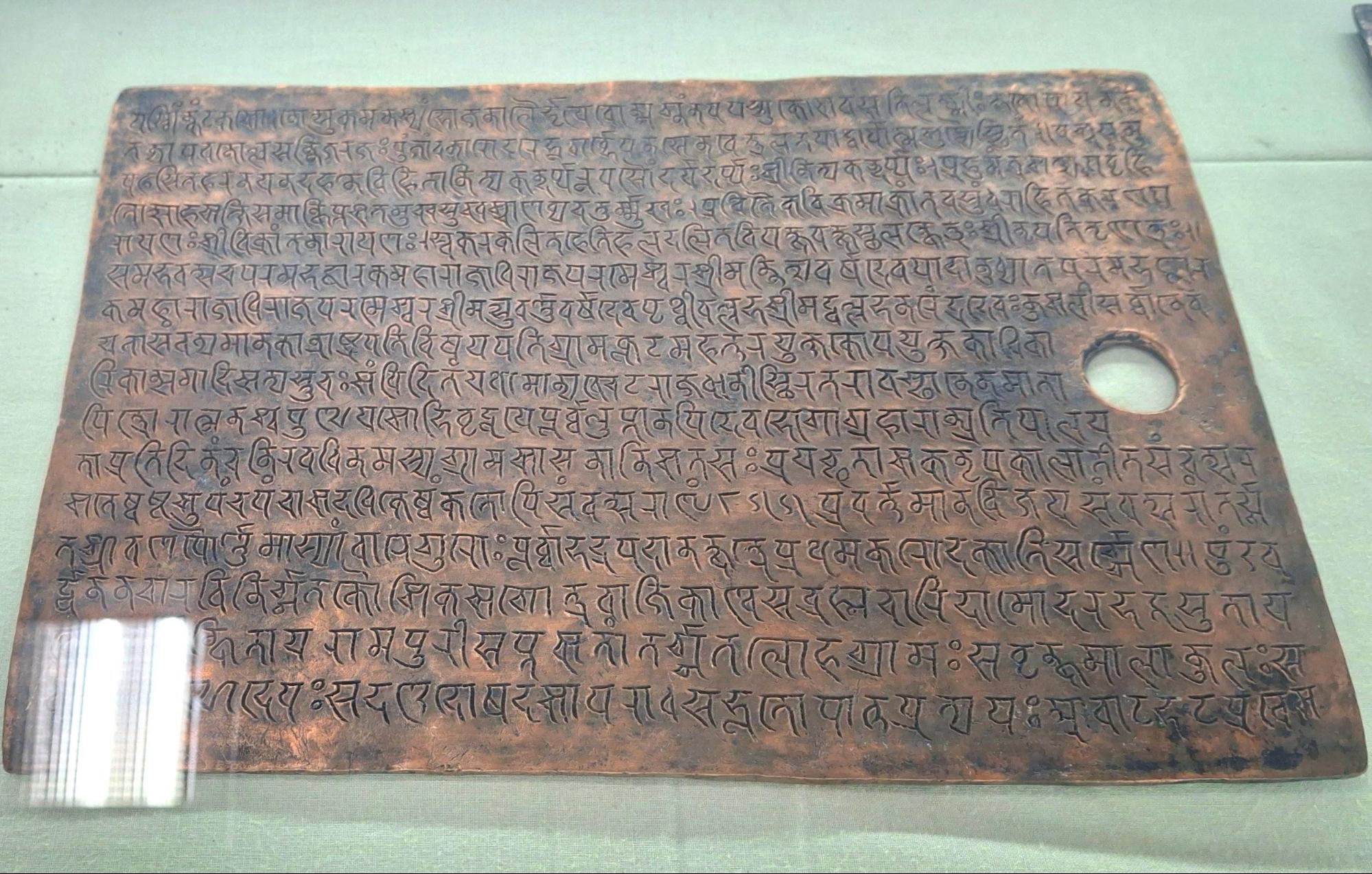

Devanagari Script

Devanagari is an Indic script primarily used for writing Marathi, Hindi, Sanskrit, and several other languages. It is widely employed in literary and official texts across various regions. The script consists of 48 fundamental characters, including 14 vowels and 34 consonants.

A notable example of the early use of Devanagari or related scripts is the Tamrapatra (copper engraving) from the reign of Rashtrakuta King Govinda IV (c. 930–936 CE). This inscription, written in Sanskrit, highlights the administrative and cultural significance of epigraphic records during that period.

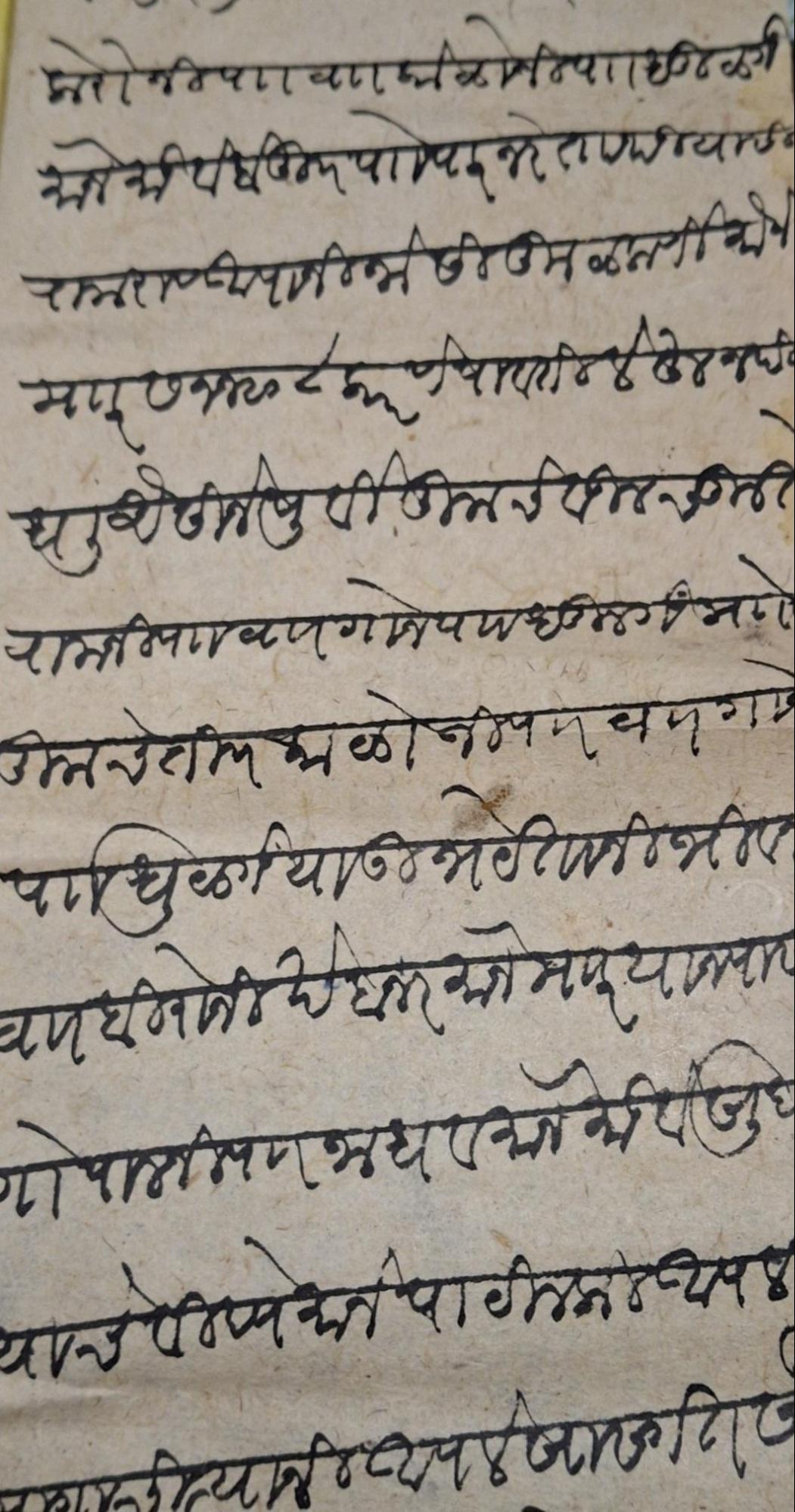

Modi Script

The Modi script, displayed at the Ahmednagar Historical Museum and Research Centre, was historically used to write Marathi. Until the early 20th century (circa 1915–1920), Modi was widely employed in administrative documents and social commentaries and was even taught in schools up to the fifth standard.

Modi gained prominence under the Maratha Empire, used by rulers such as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, Shahu Maharaj, and the Peshwas for military communication and confidential political correspondence. Its distinct cursive style allowed for continuous writing without lifting the pen, making it efficient for record-keeping. Today, documents written in Modi are rare, and even fewer people can read the script, making it an invaluable part of Maharashtra’s linguistic heritage.

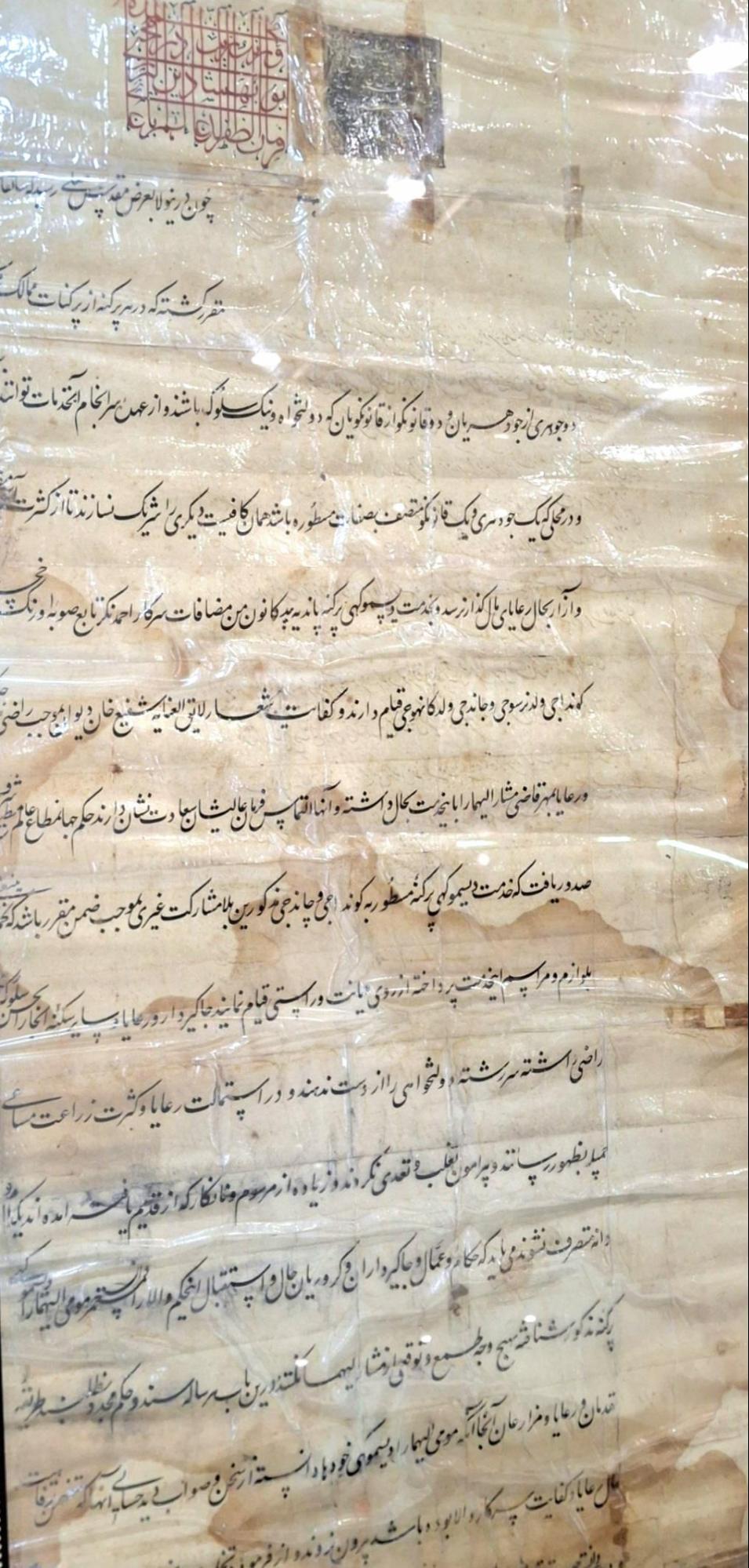

Perso-Arabic Script

The Perso-Arabic script was widely used in South Asia, particularly during the Mughal era, when Persian served as the language of administration. Official documents, including sanads (charters or grants), were meticulously written in Persian calligraphy on parchment or handmade paper, often adorned with imperial seals in wax or gold.

The Ahmednagar Historical Museum houses an impressive collection of manuscripts from the Mughal Era. Among these notable artifacts is a remarkably preserved 17th-century sanad (charter) issued in 1669 at Bhingar, Alamgir. This significant document, meticulously written in Persian script, bears the distinctive gold seal of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Emperor. It was formally granted to Kondaji Vlad Narsoji. Very remarkably, Sanads functioned as essential official decrees for land grants, titles, and tax exemptions, serving as crucial administrative records. This manuscript, in many ways, provides valuable insights into linguistic shifts, evolving documentation styles, and the local history of Alamgir in the district.

Sources

A. Teemant, & S. Pinnegar. (2007). Understanding Language Acquisition Instructional Guide. Brigham Young University-Public School Partnership. Language Acquisition: An Overview, EdTech Books.https://edtechbooks.org/language_acquisition…

Arun Gajanan Musle. 2017. Kolhati.In G.N. Devy and Arun Jakhade (eds.).The Languages of Maharashtra, People’s Linguistic Survey of India Vol. 17, part 2. Orient Blackswan: Hyderabad.

Luke Koshi. 2016. Explainer: The reorganization of states in India and why it happened. The News Minute. https://www.thenewsminute.com/news/explainer…

Mohan Ransing. 2017. Thakaree. In G.N. Devy and Arun Jakhade (eds.). The Languages of Maharashtra, People’s Linguistic Survey of India Vol. 17, part 2. Orient Blackswan: Hyderabad.

Muzaffar Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. 2012. Writing the Mughal World. Columbia University Press.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011. Census of India 2011: Language Census. Government of India.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

ScienceDirect. "Devanagari." ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochem…

Last updated on 18 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.