Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Satavahana Influence and the Tarhala Coin Hoard

- Spread of Buddhism and the Patur Caves

- Vakatakas and their Connection to Patur

- Yadava Rule and the Hemadpanthi Mandirs of Akola

- Akola Town and Akol Singh

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate

- Bahmani Rule and Narnala Fort

- Imad Shahi Rule and the Berar Sultanate

- Siege at Naranala and the Campaigns Under Murtaza Nizam Shah I

- Mughal Advance and Establishment of Rule

- Turbulence and the Campaigns of Malik Ambar

- The Treachery of Khan Jahan Lodi

- The Great Famine of 1630

- Maratha Expansion and the Rise of Raghuji Bhosale I

- Battle of Kumbhari, 1773

- The Battle of Argaon (1803) and the Second Anglo-Maratha War

- Sant Gajanan Maharaj

- Colonial Period

- Local Dissent and the Warhad Samachar

- The Forest Satyagraha at Dahihanda

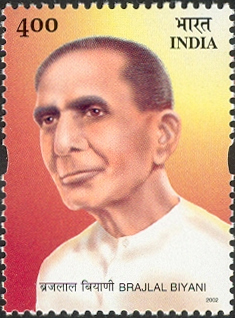

- Brijlal Biyani and the Freedom Struggle in Akola

- The Akola Pact and the Demand for Regional Autonomy

- Post-Independence

- Sources

AKOLA

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Akola district is situated in the north-central portion of Maharashtra and forms part of the Vidarbha region within the Amravati Division. Over the course of its history, Akola has come under the rule of various political powers, traces of which remain scattered across the region.

Under Mughal rule, the town of Balapur, which lies in the district, briefly served as a fortified military post of much significance. In 1697 CE, the town of Akola was granted to Asad Khan, a nobleman in the court of Aurangzeb, who constructed the fort known as Asadgad. During the late 19th century, portions of Akola’s territory were reorganised among neighbouring districts as part of broader administrative reforms in Berar Province. In 1956, with the States Reorganisation Act, the taluka of Washim and Mangrulpir were joined to Akola. These remained part of the district until 1998, when Washim was constituted as a separate district, thereby bringing Akola to its present configuration.

Etymology

The origin of the name Akola is explained through several local traditions. One of which attributes the name to a local figure known as Akol Singh, who is said to have fortified the village with mud walls after witnessing a hare chase a dog; an event regarded as a favourable omen. According to this account, the settlement was named after him.

Alternative etymologies have also been proposed. One theory suggests a derivation from the word "adka," meaning marketplace, implying that the town may once have served as a commercial centre. Another explanation links the name to the Marathi word Akol, meaning end or boundary, possibly referring to the town's position in earlier territorial arrangements.

Ancient Period

The territory that now forms the Akola district has, at various times, fallen under the authority of different kingdoms. Its early history is difficult to reconstruct in full due to the scarcity of information. However, available archaeological findings and a few literary references allow for a general outline, particularly when considered in relation to the broader histories of Vidarbha and Berar (the cultural and political spheres to which Akola has historically belonged).

Satavahana Influence and the Tarhala Coin Hoard

One of the earliest dynasties to leave a lasting imprint on the Akola region was the Satavahanas, who ruled large parts of the Deccan region between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE. Their presence in this area is attested by the discovery of a hoard of potin coins at Tarhala in 1939, a village which at that time was part of Akola but now lies in Washim district. Fascinatingly, the hoard contained over 1,200 potin coins, many of which featured an elephant with an uplifted trunk on the obverse and the Ujjayini symbol on the reverse. Notably, both of these motifs are regarded to be common in Satavahana numismatics.

The coins bear the names of rulers like Gautamiputra Satakarni, Pulumavi, Vasishthiputra Satakarni, and Skanda Satakarni. What is more striking, however, is that some names found in the coins, such as Kumbha and Shaka Satakarni, do not appear in the traditional Puranic lists of Satavahana rulers. This has led many historians to suggest the existence of regional Satavahana rulers specific to the Vidarbha region. Akola’s place within this region, and close proximity to Washim, in many ways, implies that it might have been ruled by a decentralised Satavahana polity during ancient times.

Spread of Buddhism and the Patur Caves

The influence of the Satavahanas in Akola is not confined to numismatic discoveries. The period is also widely known for the encouragement and dissemination of Buddhism across the Deccan, and architectural evidence within the district affirms its place within this broader cultural movement. One such site in the district is the Patur Caves, located near the Renuka Mata Mandir along the Patur–Balapur road.

These rock-cut chambers, hewn from the basaltic rock of the Deccan plateau, consist of simple viharas believed to have served as monastic residences. Their architectural features, such as a verandah with square pillars and a now-damaged seated figure, are consistent with early Buddhist cave traditions elsewhere in Maharashtra. Notably, the site was brought to the notice of the wider academic world in 1730 by the English antiquarians Edmund Lyon and Robert Gill, both of whom undertook exploratory surveys across the Deccan. Later, Henry Cousens, in his systematic fieldwork during the late nineteenth century, classified the caves as Buddhist in character. Its presence here, in many ways, attests to Akola’s participation in the broader Buddhist religious and trade networks of the time. It also suggests that Buddhist communities were active in the district during the early centuries CE.

Vakatakas and their Connection to Patur

With the decline of Satavahana authority in the Deccan, political power in the Vidarbha region gradually passed into the hands of the Vakatakas. Of the several branches into which this dynasty came to be divided, the Vatsagulma line is of particular relevance to the present Akola district. Their capital, Vatsagulma, is now identified with modern Washim, which lay not far from the eastern boundary of Akola, suggesting that the district may have fallen within their immediate sphere of influence. Among the traces that hint at this reach, notably, the Patur Caves within the district have been reconsidered by recent scholars as bearing signs of Vakataka patronage during a later phase of development.

Though the caves are generally believed to have been initiated during the Satavahana period, A. Jamkhedkar (2011), in his Marathi work Kon Hote Vakataka?, argues that their completion may be attributed to the reign of Vakataka king Harishena (c. 480–510 CE) and his minister Varahadeva. Both figures are more commonly associated with the Ajanta caves in present-day Sambhaji Nagar, which received substantial patronage under their rule. This suggestion, if accepted, would place the Patur Caves among the sites linked to the Vakataka revival of rock-cut architecture in the 5th century CE.

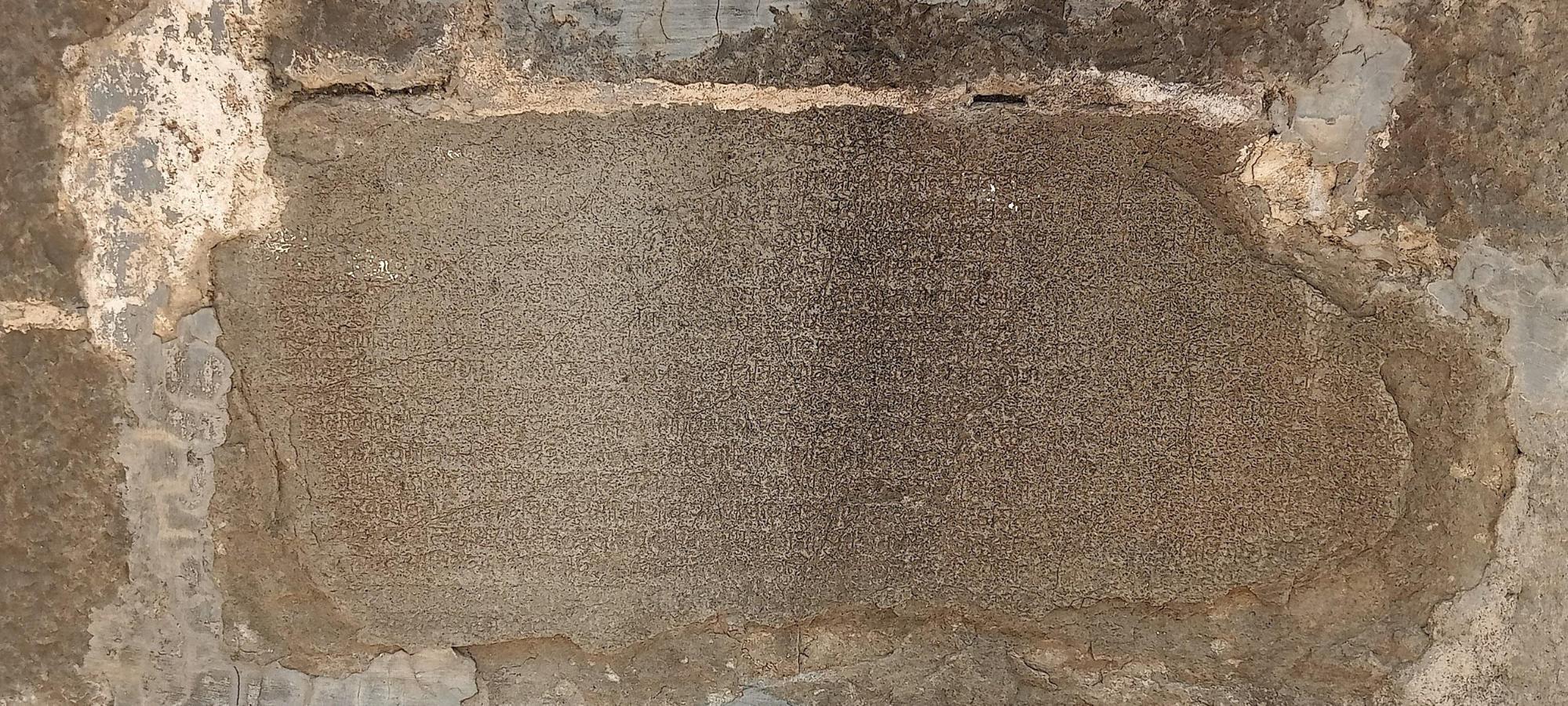

In recent years, further evidence has led to the proposition that the caves may have had Shaiva associations. A Parvati sculpture, reportedly dating to around 450 CE and recovered from Cave No. 2, is now housed in the Nagpur Central Museum. The main cave features a square sanctum, where people say that a structure suggestive of a shivling lies. This, along with two inscriptions in Petikashirsha Brahmi found outside the caves, has been tentatively dated to the Vakataka period.

By the mid-6th century CE, Vakataka authority had waned, and the region came under the rule of the Early Chalukyas of Badami, who had established their capital in northern Karnataka. Their influence extended into the Vidarbha region and likely included parts of present-day Akola.

In the mid-8th century, Dantidurga, founder of the Rashtrakuta dynasty, overthrew the Badami Chalukyas and rose to power across the Deccan. The Rashtrakutas retained control over Vidarbha and Berar for nearly two centuries, until their decline in the late 10th century.

Around 973 CE, the Rashtrakutas were overthrown, and the Western Chalukyas, also known as the Chalukyas of Kalyani, attempted to establish their authority in the region. However, Vidarbha initially fell under the influence of the Paramaras of Malwa. It was not until 995 CE that the Western Chalukyas finally reconquered Vidarbha and re-established their dominion.

Yadava Rule and the Hemadpanthi Mandirs of Akola

By the 12th century CE, the region came under the rule of the Yadava dynasty, whose capital was Devagiri (modern Daulatabad). Originally vassals of the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani, the Yādavas declared independence under Bhillama V and further consolidated their rule under his successor, Singhana II (r. c.1200–1247 CE). Interestingly, epigraphic and local accounts suggest that parts of Akola were integrated into this administrative apparatus during this phase of regional conquest and stabilisation.

Their advance into the region is locally remembered through figures such as General Kholeshwar, who, according to tradition, subdued Tekkali (modern Barshi Takli) on behalf of King Singhana II. An inscription found inside the Kalanka Devi Mandir, built in 1177 CE (Śaka 1098), refers to the rule of Hemadrideva, a local chief later defeated by Kholeshwar. While Hemadrideva’s precise political status remains debated, his defeat is taken to signify the firm establishment of Yadava authority in the region.

Fascinatingly, to this day, the figure of Kholeshwar remains etched in the landscape of Barshi Takli, most notably through a Mandir that bears his name.

Situated on the outskirts of the town, on the banks of the Vidrup River, stands the Kholeshwar Mandir, a structure of considerable antiquity and distinct character. It is important to note, however, that the origin of the Mandir’s name is subject to multiple interpretations. The garbhagriha of the Mandir notably can be accessed by descending a steep flight of steps into a narrow cavity which has led some to suggest that the name derives from khol, the Marathi word for depth. Whether the nomenclature refers directly to a Yadava general or is merely coincidental, it nonetheless evokes the memory of the dynasty’s northern campaigns in this region.

However, what can be said with certainty is that the Mandir, built from locally quarried black stone and constructed without mortar, adheres to the stylistic conventions popularised under the Yadava regime. Notably, beyond their political role, the Yadavas left a lasting architectural legacy in Maharashtra through their minister Hemadri, also known as Hemadpant. He is widely credited with popularising a distinctive style of temple construction that later came to be known as Hemadpanthi architecture.

Characterised by the use of locally available black stone and lime without mortar, Hemadpanthi Mandirs are found across present-day Maharashtra and often attributed to Yadava patronage, either directly or through local chieftains under their suzerainty. In Akola district, several mandirs built in this style, especially in areas like Balapur and Akot, attest to Yadava influence.

Among the enduring remains attributed to this era is the Choubari Barav, a stepped well located in the village of Pinjar (Barshi Takli taluka). Believed to have been constructed in the 12th century in Hemadpanthi style, the well retains water through the year and is said to have served ritual purposes. Notably, Devotees and local royalty are believed to have bathed here prior to entering the Mandir.

At Pinjar, in Barshi Takli taluka, stands the Mahadev Mandir, also referred to as the Kapileshwar Mandir, constructed in the Hemadpanthi style with black stone. According to local accounts documented by RJ Dipak Wankhede, a partially legible inscription inside the nandi mandapa preserves the word Vdiptiprashasti, though the rest remains too weathered to interpret.

Akola Town and Akol Singh

It is likely that Akola town had already begun to take shape, perhaps even as a fortified settlement, during or slightly before the Yadava period. While the Yadavas left behind a clear architectural legacy in the region, the early history of Akola town remains uncertain, owing to the absence of archaeological or textual evidence.

What is known, however, is that a ruler (about whom little is known) is believed to have fortified the town in its early days. He is credited with constructing the first protective wall around the village. Interestingly, there is a rather peculiar story behind this. According to local tradition, Akol Singh witnessed a hare chasing a dog, an unusual and auspicious sign, and took it as a divine indication to fortify the area with an earthen wall. He is believed to have been a Rajput ruler, though little historical evidence survives to confirm his identity or the period in which he lived. The town’s very name, Akola, is often associated with him, though whether this is rooted in fact or folklore remains open to interpretation.

Medieval Period

Delhi Sultanate

Following the decline of the Yadava dynasty, Akola, along with the rest of Berar region, was annexed by the Delhi Sultanate under the Tughlaq dynasty. In 1298 CE, Alauddin Khilji, son-in-law of the Sultan of Delhi, launched a successful military campaign into the Deccan against King Ramachandra of the Yadavas. This invasion was part of a broader effort by the Delhi Sultanate to extend its control southward.

By around 1311 CE, the Yadava territories were fully annexed into the Delhi Sultanate, and governance of the Deccan was entrusted to imperial officers stationed at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad). It is likely that parts of present-day Akola were brought under the administrative and military influence of these northern rulers during this period of expansion and consolidation.

Bahmani Rule and Narnala Fort

The authority of the Delhi Sultanate began to wane by the mid-14th century, and the wider Deccan region witnessed the rise of new regional powers. Among them, the Bahmani Sultanate, established in 1347 by Ala-ud-Din Bahman Shah, rapidly expanded its influence across large parts of the plateau. The area that now forms Akola district, then part of a loosely held frontier zone, gradually came under Bahmani control in the decades that followed.

To bring order and stability to their growing dominion, the Bahmani rulers undertook a major administrative reorganisation. They divided their territories into five provinces, one of which (Berar) was newly carved out to administer the northern reaches. This new province included the Akola region and was strategically important due to its fertile land, frontier location, and access to trade routes leading towards Khandesh and Malwa.

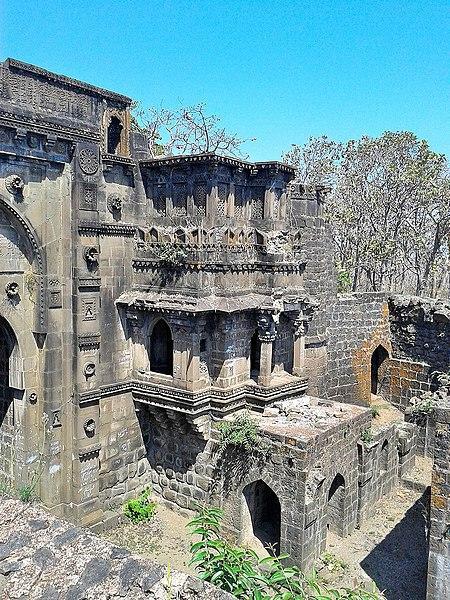

Though distant from the Sultanate's early capitals at Gulbarga and later Bidar (both of which lie in Karnataka), Berar's fertile plains and frontier position between northern and southern India rendered it strategically valuable. To secure their northern approaches, the Bahmani rulers established a regional headquarters at Ellichpur (now Achalpur in Amravati district) and fortified key passes and hilltops along the Satpura ranges. It was during this period that Narnala, a rugged hill fort near present-day Akot taluka, assumed heightened importance. Its location, in many ways, made it an ideal watchpoint over the plains of eastern Berar and a stronghold against incursions from the east (a feature which perhaps contributed to its sustained prominence under successive dynasties in the centuries that followed, as will be seen in the ensuing sections).

By the early 15th century, as threats from Gond rulers grew more frequent, Sultan Ahmad Shah I Wali of the Bahmani dynasty took personal interest in the region. In 1425, following an expedition to quell disturbances in eastern Berar, he temporarily established his camp at Ellichpur. Recognising the vulnerability of the province’s open terrain, he ordered the strengthening of nearby forts, among them Narnala. Contemporary accounts suggest that extensive fortification works were undertaken here under his direction. In time, it would become the base for further developments under the Imad Shahi dynasty, but its political emergence began firmly under Bahmani authority.

Imad Shahi Rule and the Berar Sultanate

As the Bahmani Sultanate weakened in the late 15th century, its provincial governors began asserting independence. In 1490, Fatehullah Imad-ul-Mulk, governor of Berar, declared himself sovereign and established the Imad Shahi dynasty, ruling from Ellichpur. Akola and its surrounding forts, including Narnala, continued to serve as important military and administrative centres under his dominion.

The dynasty maintained its independence precariously amidst growing pressure from neighbouring states. The later years of its rule were marked by internal dissension and declining authority. In the mid-16th century, Burhan Imad Shah, the last ruler of the line, faced open rebellion from his minister Tufail Khan, who laid siege to Narnala Fort. The betrayal proved fatal to the dynasty, and Berar was soon annexed by the Ahmadnagar Sultanate.

Siege at Naranala and the Campaigns Under Murtaza Nizam Shah I

With the weakening of the Imad Shahi dynasty, which had until then governed Berar from its regional seats of power such as Ellichpur and Narnala, the sultans of Ahmadnagar turned their attention northward. What followed was a prolonged and calculated campaign by Murtaza Nizam Shah I of Ahmadnagar, which culminated in the absorption of Berar, Akola included, into the Ahmadnagar Sultanate.

In 1572, according to the Maharashtra State Gazetteers (The Imadshahi of Berar, Chapter XI), Murtaza entered into a treaty with Ali Adil Shah of Bijapur, whereby Ahmadnagar would annex the territories of Berar and Bidar, while Bijapur would expand into the present-day Karnataka region. Though this alliance served to partition the Deccan between the two major powers, it also unleashed a wave of ambition and rivalry. Ahmadnagar’s claim over Berar rested on the pretext of restoring authority to the young Burhan Imad Shah, then under the regency of his minister Tufail Khan.

An envoy was dispatched from Ahmadnagar to demand that Tufail return power to Burhan. Tufail, however, rightly suspected a veiled threat of invasion. His son, Samser-ul-Mulk, advised against compliance, and the envoy was turned away. Even as the diplomatic exchange unfolded, Murtaza I had already begun his military advance. Berar was overrun and its lands distributed among Ahmadnagar’s nobles, marking the beginning of the end for the Imad Shahis.

The confrontation quickly reached Akola’s and the fort of Narnala became the last major seat of contention. After failed negotiations and minor engagements near Bidar and Mahur, Tufail Khan withdrew to Narnala, while Samser-ul-Mulk retreated to Gavilgad. Murtaza launched an aggressive siege of Narnala under his vizier Asad Khan.

The siege extended for more than a year, from 1573 into early 1574. Despite heavy bombardment, the garrison resisted fiercely. An attempted betrayal from within was thwarted by the defenders. Eventually, in April 1574, Ahmadnagar’s troops breached the gates, and Tufail Khan fled, only to be captured shortly thereafter. With Narnala lost, the remaining defenders at Gavilgad lost heart. Samser-ul-Mulk was arrested by his own men and handed over to Murtaza.

Thus, the rule of the Imad Shahis in Akola came to a close. Tufail Khan, his sons, Burhan Imad Shah, and other members of the dynasty were imprisoned in Lohagad Fort (in Pune district, Maharashtra), where they passed away soon after, it is said, by poisoning. Akola, along with the rest of Berar, was now brought firmly under Ahmadnagar control, where it would remain until the Mughal invasion of 1596.

Mughal Advance and Establishment of Rule

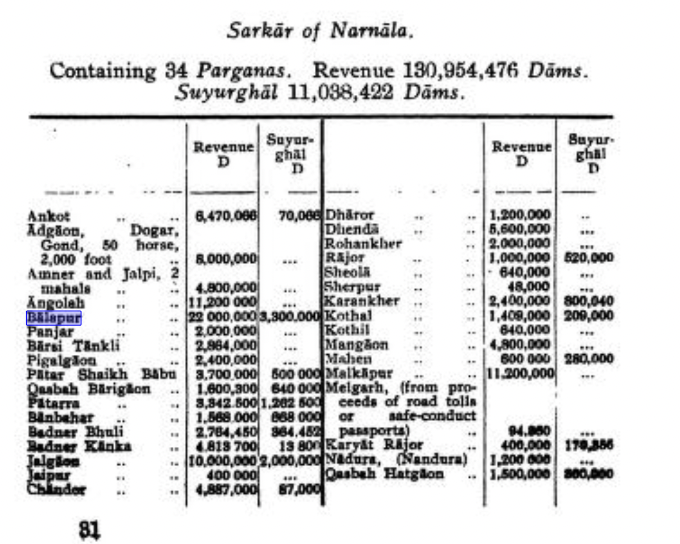

The closing years of the sixteenth century witnessed a marked decline in the authority of the Ahmadnagar rulers in Berar. This circumstance was not long unexploited. Khan-i-Azam, the foster-brother of Emperor Akbar and then governor of Malwa, led a northern force into Berar, sacking Achalpur and advancing through what is now the Akola district. In 1595, the province was annexed to the Mughal Empire. The following year, Prince Murad, Akbar’s fourth son, assumed governorship of the region and established his headquarters at Balapur, which henceforth grew into a seat of administration and military control.

It is notably recorded in the Mughal record Ain-i-Akbari that many parts of the present-day district during this time fell under the sarkar of Narnala, with Balapur and Shahpur marked as principal towns. Abul Fazl makes mention of streams near Balapur said to yield small precious stones, which were collected and preserved as curiosities. Near the vicinity of Balapur, arose the settlement of Shahpur, where Prince Murad was also known to have resided.

Turbulence and the Campaigns of Malik Ambar

Despite nominal control, Mughal possession of Berar remained far from secure. Resistance to Mughal authority persisted under the leadership of Malik Ambar, a capable and restless general of the Nizam Shahi dynasty of Ahmadnagar. Throughout the early seventeenth century, Malik Ambar conducted a series of incursions into Berar, at times occupying it in its entirety, Akola included, and establishing his own administrative arrangements.

Emperor Jahangir, upon ascending the throne in 1605, endeavoured to stabilise the region by appointing Prince Parvez as viceroy in 1609. The prince’s administration, however, lacked vigour, and Berar continued to be a theatre of contest between Mughal officers and the forces of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. The instability rendered Akola a frequent frontier in this prolonged conflict.

The Treachery of Khan Jahan Lodi

The political climate worsened during the years of Shah Jahan’s rebellion against his father. Though Mughal control over Balapur and Akola was not entirely lost, it grew precarious. Khan Jahan Lodi, a noble of Afghan descent who had been entrusted with the governorship of Berar, entered into secret negotiations with the Nizam Shahi court. He sold the Balaghat region, including Akola and its dependencies, for a consideration of lakhs of rupees to Murtaza Nizam Shah II. Consequently, the Mughal garrisons withdrew, and the Ahmadnagar Sultanate’s influence expanded over the district.

Upon accession to the throne in 1628, Shah Jahan repudiated the sale and issued a firm demand for the restoration of all military outposts. When the Nizam refused to surrender Lodi, who had sought refuge in his court, the emperor initiated a campaign, marching from Burhanpur to reassert dominion over Berar. Akola was brought once again under firm Mughal control following this expedition.

It is important to note that under Mughal administration, Berar was divided into Balaghat (the southern upland) and Payanghat (the northern plain), with the two separated by the natural edge of the Deccan plateau. Within this framework, Akola, Balapur, Akot, and Murtizapur fell within Payanghat, while Basim (Washim) and Mangrul belonged to Balaghat. Balapur emerged as the chief centre of Mughal authority in the region, and a permanent garrison was maintained there.

By the latter part of the seventeenth century, the town of Akola itself was held as a jagir by Asad Khan, the prime minister of Emperor Aurangzeb. His local representative, Khwaja Abdul Watif, is credited with the construction of the fortification walls, thereafter known as Asadgarh, a structure which, though now largely in ruins, long served to protect the town and assert Mughal presence in the district.

The Great Famine of 1630

This phase of Mughal administration was, however, soon overshadowed by natural calamity. In the year 1630, Akola and the greater part of Berar suffered the effects of a devastating famine, which was brought on by the failure of the monsoon and exacerbated by military operations. Contemporary accounts record unspeakable misery, people bartered their lives for a morsel of food, and in their desperation, turned to the flesh of dead animals and, at times, of one another. Cannibalism, though unspeakable, is repeatedly mentioned in records later compiled in the district Gazetteer. Even the bones of the deceased were said to have been ground into flour. Depopulation followed, and the effects of the calamity lingered long after the rains returned.

Maratha Expansion and the Rise of Raghuji Bhosale I

Following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Mughal Empire’s authority over the Deccan steadily waned. In 1724, Chin Qilich Khan, the Mughal Subahdar of the Deccan, declared independence and founded the Hyderabad State under the title Asaf Jah I. While Berar, including Akola, nominally passed into the Nizam’s dominion, the ground reality was more complex. The Marathas were asserting increasing influence over the region.

As early as 1719, Emperor Farrukhsiyar had formally conferred upon the Marathas the rights of chauth and sardeshmukhi over Berar. The recognition forced the Nizam to tolerate Maratha fiscal claims even while he continued to claim administrative control. In practice, Akola and the surrounding parganas were subjected to overlapping revenue claims by both the Nizam’s jagirdars and the Maratha revenue officers.

It is noted in the district Gazetteer that during this period, peasants were often forced to make dual payments, leading to widespread discontent. Numerous villages in Akola taluka were abandoned, reflecting the economic strain of this contested sovereignty.

The principal Maratha figure to assert control over Berar during this period was Raghuji Bhosale I, originally raised in the household of Kanhoji, a military officer of some standing in Gondwana. Though Kanhoji treated Raghuji as an adopted heir for a time, the birth of his own son Rayaji created tensions, eventually prompting Raghuji to seek the support of Chhatrapati Shahu I. With Shahu’s backing, Raghuji overthrew his former guardian and consolidated his hold over Nagpur, Berar, and Gondwana by the 1740s.

As Raja of Nagpur, Raghuji Bhosale I firmly established Maratha sovereignty over Berar, and Akola became part of this expanding eastern domain. His authority was later recognised even in the Treaty of Deogaon (1803), where the British referred to the Nagpur Bhosales as the ruling house of Berar.

Battle of Kumbhari, 1773

By the latter half of the 18th century, the Akola district became a site of military and political consequence in the succession dispute within the Nagpur branch of the Bhosale dynasty. The death of Raja Janoji Bhosale in 1772 left the question of succession unresolved. His brother, Sabaji Bhosale, supported by Peshwa Madhavrao I of Pune, advanced his claim to the Nagpur gadi. In opposition stood Mudhoji Bhosale, father of the minor Raghuji Bhosale II, who had previously been adopted by Janoji. Mudhoji, though initially operating from a position of relative weakness, secured the covert support of the Nizam of Hyderabad.

The conflict culminated in the Battle of Kumbhari, fought in January 1773 near the village of Kumbhari, situated within the present-day Akola district. Owing to its proximity to the boundary between Maratha-held Berar and areas influenced by the Hyderabad State, the location bore strategic significance.

Contemporary records suggest the engagement was prolonged and hard-fought. Despite setbacks in the early stages of the battle, Mudhoji Bhosale ultimately prevailed, securing control over Nagpur and its dependencies, including Berar. His assumption of power was followed by a realignment in the region’s political relations, particularly with the Hyderabad State.

The Battle of Argaon (1803) and the Second Anglo-Maratha War

Following the succession conflict at Kumbhari in 1773, which secured Mudhoji Bhosale’s control over the Nagpur State, the region around Akola remained under Maratha rule for several decades. However, internal divisions among the Maratha Confederacy, particularly between the Bhosales of Nagpur, the Scindias of Gwalior, and the Peshwas of Pune, grew more pronounced over time. Meanwhile, the British East India Company, backed by its longstanding alliance with the Nizam of Hyderabad, was steadily expanding its presence across the Berar region.

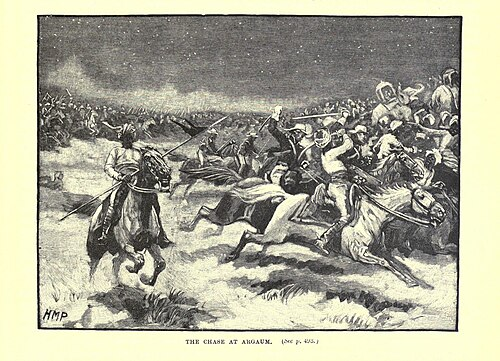

It was in this atmosphere that the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805) broke out. The district of Akola became the site of one of its key engagements. On 28 November 1803, British forces under Major-General Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) marched into the area near Argaon (now Adgaon village in Telhara taluka). Facing them was a joint army of the Bhosales of Nagpur, under Raghuji Bhosale II, and the Scindias of Gwalior, under Daulat Rao Scindia. The two factions had formed an alliance in a last attempt to resist British expansion.

The next day, 29 November, a major battle unfolded near Sirsoli, a village about three miles south of Argaon. Early in the encounter, part of the British line gave way under heavy cannon fire, raising fears of a defeat. However, Wellesley quickly reorganised his troops and launched a counterattack. The Maratha forces were soon overwhelmed. Their artillery and baggage were seized, and the defeat marked a turning point in the campaign.

The outcome of the battle effectively ended Maratha resistance in Berar, and soon after, Raghuji Bhosale II signed the Treaty of Deogaon (December 1803). Under the treaty, he ceded large territories such as Cuttack (present-day Cuttack, Odisha) and Balasore (present-day Balasore, Odisha), and agreed to limit diplomatic engagement with other powers. Though the Nagpur State remained under Bhosale rule, it now operated under British supervision, with diminished sovereignty.

The Battle of Argaon, thus fought within the bounds of the present-day Akola district, was, in many ways, a significant moment in the district's political history. It marked the final collapse of Maratha power in the region and the formal commencement of British political influence in the region.

Sant Gajanan Maharaj

Sant Gajanan Maharaj made a profound contribution to the spiritual heritage of Maharashtra, revitalising faith through his enigmatic presence as a perfect Avadhuta (a saint beyond all worldly conventions). His origins are a celebrated mystery, as he was first seen as a young man on February 23, 1878, in Shegaon. This town, then a part of Akola district (and now in Buldhana district), became his karmabhoomi and a major pilgrimage centre. He was discovered picking leftover food grains, a sign of his complete detachment from ego and social norms.

Unlike saints with known lineages, Gajanan Maharaj had no known birth name, family, or external Guru; he was widely regarded as a self-realised Paramahansa and an incarnation of Lord Ganesha. He spent his entire life in and around Shegaon, guiding devotees through his simple, often cryptic, actions rather than long discourses. He performed countless miracles to bolster the faith of the common people, teaching the unity of God and the importance of selfless service, summed up in his famous mantra "Gan Gan Ganat Bote." His legacy continues through the massive charitable, educational, and spiritual work of the Shegaon Sansthan.

Colonial Period

The formal involvement of the British in the administration of Akola began in 1853, when the Nizam of Hyderabad, under pressure from mounting debts, consented to cede the Berar province to the East India Company for its management. While nominal ownership remained with the Nizam, real authority was exercised by British officials appointed under the Resident at Hyderabad.

Berar, until then governed as a frontier zone under the dominion of the Hyderabad State, was now subject to reorganisation. The British divided the territory into East Berar, with its headquarters at Amravati, and West Berar, which included the area now constituting Akola district.

As part of the ensuing administrative restructuring, the district of Akola was formally established in 1864, along with Amravati district. In the same year, the region of Wun (now Yavatmal district) was also constituted as a separate administrative unit. Additional changes followed: the sub-divisions of Malkapur, Chikhli, and Mehkar, earlier part of West Berar, were separated and grouped into a new district called South-West Berar. This unit was renamed Mehkar district in 1865. Subsequently, in 1867, Buldhana was selected as the district headquarters for the reorganised tract.

The following year, in 1868, further reorganisation led to the creation of Bashim district (present-day Washim district as it was called then), while the earlier districts of Achalpur and Mehkar, both of which had functioned briefly, were dissolved. Throughout these developments, the British maintained oversight through the office of the Agent of the Resident, stationed at Amravati, who was tasked with supervising the administration of Berar, including Akola. By the late nineteenth century, the Berar region was merged with the adjoining Central Provinces, giving rise to the larger political entity known as the Central Provinces and Berar. Akola thus came to be incorporated within this expanded colonial framework.

Some further changes came in 1905, when the district was comprehensively reconstituted. Of the original talukas, Akola, Balapur, and Akot were retained. In contrast, Khamgaon and Jalgaon were transferred to other units. In their place, the talukas of Murtizapur, Basim (Washim), and Mangrul were brought under Akola's jurisdiction.

The 1901 Census recorded the total population of Akola district at 7,54,804, across an area of 4,110 square miles. In comparison to other districts in the Central Provinces and Berar, Akola ranked 10th in area and 4th in population, with a population density of 184 persons per square mile, exceeding the regional average of 120.

Local Dissent and the Warhad Samachar

In parallel with these developments, Akola also witnessed the emergence of regional journalism as a channel for civil expression. Among the earliest such publications was the Warhad Samachar, an Anglo-Marathi weekly published from Akola between 1865 and 1918. It served as a forum for articulating public grievances and reporting on matters of local concern.

An edition dated 6 May 1877 notably criticised the conduct of British officials, drawing attention to the alleged murder of Ramdayal, a municipal peon from Akola, and the arrest of a local resident by Chief Commissioner Mr. Morris for accessing a public well. Such reports marked the growing presence of a local print culture that engaged critically with colonial administration and reflected the stirrings of political awareness in the district.

The Forest Satyagraha at Dahihanda

By the early 20th century, discontent against colonial forest policies began to take organised shape in parts of Akola district. One of the earliest expressions of this discontent occurred in the village of Dahihanda, where locals resisted the restrictions imposed under British forest laws that curtailed access to grazing, firewood, and minor forest produce.

The Forest Satyagraha, as it came to be known, emerged as part of a larger campaign in the Vidarbha region, led by Bapuji Ane and other Gandhian activists. In Dahihanda, villagers defied the colonial regulations, asserting traditional rights over forest use. Although non-violent in method, the protest marked a visible challenge to British authority and contributed to the broader civil disobedience movement that was gathering momentum across the country.

Brijlal Biyani and the Freedom Struggle in Akola

Among the leading figures in Akola’s nationalist activity was Brijlal Biyani (1896–1968), often referred to as Vidarbha Kesari for his contributions to public life and the freedom struggle. Born in Akola, Biyani was educated at Morris College, Nagpur, where he came under the influence of Gandhian ideals.

He played an active role in the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920) and was imprisoned for participating in protests against British-imposed salt laws and forest regulations. His leadership in movements such as the Dahihanda Salt Satyagraha and the Jungle Satyagraha cemented his reputation as a key regional figure in Vidarbha’s resistance to colonial rule.

Biyani’s influence extended beyond activism. He served in the Central Provinces and Berar Legislative Council (1927–1930), later becoming Finance Minister of the erstwhile Madhya Pradesh State after independence. His contributions were memorialised through the founding of the Shri Brijlal Biyani Shiksha Samiti (1969) and the naming of educational institutions, including the Brijlal Biyani Science College in Amravati.

The Akola Pact and the Demand for Regional Autonomy

In the final years of British rule, questions concerning the future organisation of provinces and the representation of diverse linguistic communities came to occupy the attention of political leaders across India. In regions such as Berar, which had long been administratively tied to the Central Provinces but was culturally and linguistically aligned with Marathi-speaking Maharashtra, this issue became particularly significant.

It was during this time that the town of Akola acquired prominence as the venue for a political agreement that sought to reconcile these regional aspirations. On 8 August 1947, a meeting was held in Akola between representatives of Western Maharashtra and those of Vidarbha, then still part of the Central Provinces and Berar. The outcome was the Akola Pact, an understanding aimed at ensuring equitable political and administrative treatment for Marathi-speaking regions after independence.

The pact proposed the formation of two distinct sub-provinces within a unified administrative framework—Mahavidarbha in the east and Western Maharashtra in the west—each with its own executive, legislature, and judiciary. Among the key figures associated with the pact was Barrister Ramrao Deshmukh, a senior leader from the Berar region.

The roots of this proposal lay in earlier demands dating back to the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms (1918), during which Marathi leaders had petitioned for a unified Marathi linguistic province. These demands were carried forward by organisations such as the Mahavidarbha Samiti, formed under the leadership of M. S. Aney, which actively campaigned for a state comprising Marathi-speaking areas from Berar, Nagpur Division, and parts of Bombay Presidency. Although the Akola Pact did not result in immediate administrative changes, it in some ways laid the foundation for future debates on linguistic state formation.

Post-Independence

After India attained Independence in 1947, the Central Provinces and Berar, which included Akola district, were integrated into the newly formed Indian Union. In the initial phase of reorganisation, this region became part of the state of Madhya Pradesh. However, Among the Marathi-speaking districts of the former Berar, including Akola, the idea of a Marathi linguistic state began to gather force in the years that followed.

In response to such demands growing across the country, a States Reorganisation Commission was organized and appointed by the Government of India in 1953 under the chairmanship of Justice Fazal Ali; they undertook a comprehensive review of state boundaries across the country. In its report submitted in 1955, the Commission recommended the formation of a separate Vidarbha State, comprising the districts of Akola, Amravati, Buldhana, Yavatmal, Wardha, Nagpur, Bhandara, and Chandrapur. However, the recommendation did not find favour with the Union Government of the time, which feared that the creation of multiple new states on linguistic lines, so soon after Partition, might endanger national cohesion.

In lieu of the Commission’s recommendation, the Berar regions were, in 1956, transferred from Madhya Pradesh to the Bombay State, as part of the broader reorganisation of state boundaries enacted that year. This administrative arrangement placed Akola district within a larger Marathi-speaking unit, though not as a separate state. A few years later, in 1960, the Bombay State was divided along linguistic lines, resulting in the formation of the modern states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. Akola remained within Maharashtra, where it continues to form a significant part of the Vidarbha region.

In the later decades of the 20th century, the administrative map of Akola underwent further reorganization. On 1 July 1998, the district of Washim was constituted as a separate administrative unit. This reorganisation involved the transfer of several talukas from the erstwhile Akola’s eastern portion, notably Washim, Mangrulpir, and Malegaon, to the newly formed district. Following the bifurcation, Akola district comprised seven talukas: Akola, Balapur, Patur, Barshitakli, Murtizapur, Akot, and Telhara.

Sources

Bipan Chandra, Mridula Mukherjee, and Aditya Mukherjee. 1999. India After Independence 1947-2000. Penguin Books, New Delhi.

C. Brown, A.E. Nelson ed. 1910. Central Provinces and Berar District Gazetteers Akola District. Vol. A - Descriptive. Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta.

Government of India. 1955. Lok Sabha Debates: Part I - Questions and Answers. Vol. 7. No. 1-26, Session 11. Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi.

Government of Maharashtra. 1977. Maharashtra State Gazetteer: Akola District. Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Gunakar Muley. 2015. Forts of Maharashtra. Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT).

Jadunath Sarkar. 1949. Ain-i-Akbari Of Abul Fazl - I - Allami. Vol. 2. Ed. 2. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta.

Kishori Saran Lal. 1950. History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Asia Pub. House.

Krishna Mohan Ganguly, tr. 1883-96. The Mahabharata: Vana Parva. Book 3, Section XCVI-VII.

Maharashtra State Gazetteer. History, Part II, Chapter 6: The Imadshahi of Berar. Directorate of Government Printing, Mumbai.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

Meadows Taylor. 1863. Sketch of the Topography of East and West Berar, in Reference to the Production of Cotton. Vol. 20. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25581242.pd…

Pranab Kumar Bhattacharya. 2010. Historical Geography of Madhya Pradesh: from Early Records. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Delhi.

Ramachandra Guha. 2008. India after Gandhi. Macmillan Publication, London.

The Economic Weekly. 1955. Reorganization of States: The Approach and Arrangements.https://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/1955_7/4…

W. W. Hunter. 1886. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India. Vol. 6. Ed. 2. Morrison & Gibb, Edinburgh.

Wikipedia, Akola District Website, Narnala.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.