Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Early Human Settlements in Kaundanyapur

- The Capital of Vidarbha and Kundinapuri in the Mahabharat

- Bhimkund and the Memory of the Pandavas

- Mauryan Administration and the Bhoja Line

- The Vakatakas and their Grant at Chammak Village

- Ellichpur as an Administrative Centre

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate

- Bahmani Sultanate

- Achalpur as the Capital of the Imad Shahi dynasty

- Ahmadnagar Sultanate and the Annexation of Berar

- Mughal and Maratha Rule

- Marathas

- Raghoji I Bhosale

- Maratha Revenue System

- Colonial Period

- Colonial Administrative Reorganization

- Struggle for Independence

- Sant Tukdoji Maharaj

- Local Newspapers

- Post-Independence

- Sources

AMRAVATI

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

The district of Amravati occupies a central position in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra and lies within the Amravati Division.It is a region of considerable antiquity and notably many references to the area are believed to appear in early literary sources such as the Mahabharat. It is popularly believed that, in ancient times, the district was part of the legendary Vidarbha kingdom which is mentioned in the epic to be a significant political entity. The Puyshni (modern Purna) River, which flows through the district, is also named in the epic. The ancient town of Kaundinyapur, situated on its banks, is also notably identified by scholars as the capital of that kingdom.

In the historical period, the district passed under various ruling powers. The fortified town of Achalpur (formerly Ellichpur) held importance under the Bahmani and later the Berar Sultanate, eventually serving as the latter’s capital. The Gawilgad Fort, commanding the Melghat hills, was successively fortified by Gond, Mughal, and Maratha rulers, indicating the region’s military value. Under British rule, the area formed part of Berar Province and later the Central Provinces and Berar. In the twentieth century, Amravati was active in the nationalist movement and produced several local leaders who took part in the struggle for independence.

Etymology

The name Amravati is generally believed to derive from the Ambadevi Mandir, located near the present-day Gandhi Square in Amravati town. The Mandir is dedicated to the goddess Amba Devi, regarded in local tradition as a form of Durga. Earlier variants of the name include Udumbravati, which appears to have been used in Sanskrit sources, and its Prakrit form Umbravati.

In modern usage, the name Amravati has remained consistent and continues to refer both to the district and its principal town. It is occasionally confused with Amaravati, the present capital of Andhra Pradesh, though the two are historically and geographically distinct.

Ancient Period

The region now forming Amravati district has, over time, fallen under the influence of different political and cultural powers. Although much of its early history remains unknown, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These traces are best understood in the context of the wider Berar and Vidarbha regions, with which Amravati has long shared geographic, political, and cultural ties.

Early Human Settlements in Kaundanyapur

However, it is important to note that, long before dynasties marked the region with inscriptions or built fortifications, some parts of the present-day Amravati district were already inhabited by early communities. The basin of the Purna River, which today traverses the district, provided fertile grounds and water for settlement. The river is identified by many scholars with the Payoshni or Payasvini mentioned in early Sanskrit literature and in the Mahabharat, suggesting that this geography was already important and known in ancient times.

The village of Kaundanyapur, situated on the banks of this river, has yielded archaeological evidence pointing to human activity dating back several millennia. Excavations conducted at the site revealed microlithic tools, polished stone implements, and red or orange pottery adorned with black bands.

Of special note is the variety of trap-rock tools recovered from the site—cleavers, scrapers, and hand-axes—implying that the inhabitants engaged in hunting and perhaps farming. Perforated hammer stones and polished celts also suggest that tool-making had become an agrarian settlement by this period.

The Capital of Vidarbha and Kundinapuri in the Mahabharat

The significance of Kaundanyapur appears to have continued through the centuries. Notably, many scholars identify it to be the site of Kundinapuri, the capital city of King Rukmin of Vidarbha who is mentioned in the Mahabharat. It is important to note that Vidarbha was believed to be a legendary and prosperous Kingdom in ancient times. In the first English translation of the Mahabharat by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (1896), the kingdom’s location is described as such, “this road leadeth to the country of the Vidarbhas– and that, to the country of the Kosalas. Beyond these roads to the south is the southern country.” The Vana Parva of the epic refers to Kundina as the seat of the Vidarbha kingdom, situating it as a notable realm in the wider politics of the epic period.

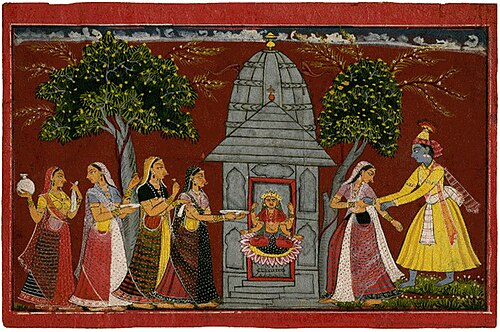

Among the most prominent stories linked to this city is that of Rukmini, the daughter of King Bhishmaka. As the narrative goes, Rukmini was pledged in marriage to Shishupala, a powerful ruler of Chedi, against her will. Secretly in love with Bhagwan Krishna, she sent him a message imploring him to rescue her. Krishna is said to have arrived at the mandir where Rukmini was praying, and carried her away to be wed in Dwarka.

Local tradition in Amravati firmly locates this episode at the Ambadevi Mandir, situated in the heart of the modern city. According to belief, this was the very Mandir where Rukmini prayed for divine intervention. Over the centuries, the Ambadevi Mandir has come to occupy a central place in the spiritual and cultural life of the region. Dedicated to Ambadevi, an incarnation of Durga, the Mandir is regarded by many as the gramdevi of the city. Its prominence is such that the name of the district itself is widely believed to be derived from this Mandir.

To this day, the Ambadevi Mandir continues to attract devotees, particularly newlyweds and those seeking blessings before major life events. The legend of Rukmini and Krishna’s union, preserved through generations, thus lends not only religious significance but also deep historical continuity to the Mandir and the city.

Bhimkund and the Memory of the Pandavas

Further north, at the edge of the Satpuda plateau, lies another site of enduring local memory—Bhimkund, also known as Neelkund, situated approximately one and a half kilometres from the town of Chikhaldara. The site consists of a strikingly deep natural spring whose waters are famed for their clear, indigo hue. The spring is located at the beginning of a steep valley that plunges over 3,000 ft.

Regional traditions associate this site with Bhima, the second of the Pandava brothers, who is said to have slain a rakshasa named Keechak at this very spot. After the battle, it is believed, Bhima washed his hands in the spring. This act of purification is said to have conferred significance to the waters, which are now visited by pilgrims and tourists alike. The surrounding area is still referred to as Keechakdara, a name that, in the view of many locals, evolved into Chikhaldara. An alternative explanation, however, links the name to the region’s characteristic mud and swampiness, derived from the Marathi and Hindi word chikhal.

Mauryan Administration and the Bhoja Line

The earliest indications of any political influence in the region now forming Amravati district appear during the Mauryan period in the 3rd century BCE. While no Mauryan inscriptions have yet been found in the district itself, a small number of references from nearby areas suggest it may have fallen within the wider sphere of Mauryan influence.

Notably, an inscription issued by a dharmamahāmātra under Ashoka, found at Deotek in Chandrapur district, indicates the presence of Mauryan administration in the nearby eastern Vidarbha region. Other insights into their presence here come from Ashoka’s fifth and thirteenth rock edicts, which mention the groups such as the Rashtrikas, Petenikas, and Bhojas; they are later associated by scholars to have held much hold over western Maharashtra, Paithan (in present-day Sambhaji Nagar), and the Vidarbha region (where Amravati lies) respectively. These were likely local ruling houses, some of whom possibly acknowledged or served as chieftains under the Mauryan authority.

Whether Amravati was directly administered by Mauryan governors or governed through local intermediaries remains uncertain, however these details provide some glimpse into the political happenings of the era in the wider region in which Amravati lies.

After the decline of Mauryan power around 185 BCE, the region witnessed the emergence of new political entities. The Sunga dynasty, founded by Pushyamitra Shunga, is known to have faced resistance from a Raja of Vidarbha, indicating that the local kingdom retained political prominence. Though the dynasty of this Raja is not definitively known, the fact that Pushyamitra—once commander-in-chief of the Mauryan army—had to engage in military campaigns against Vidarbha suggests that the region was far from a passive frontier. This period, while poorly documented in inscriptions, hints at the presence of an indigenous political authority.

By the 1st century BCE, the Vidarbha region had come under the control of the Satavahana dynasty, whose rule over the Deccan would endure for over four centuries. The Satavahanas played a central role in establishing trade routes, minting coinage, and promoting religious and civic institutions. Amravati was likely part of the inner territory of this empire.

However their reign was also marked by many incursions. According to the Gazetteer (1909), the region endured periodic incursions by the Sakas, Pallavas, and Yavanas. However, Satavahana control was largely restored by Vilivayakura II in the mid-2nd century CE, who consolidated power and extended dynastic influence once more over the Vidarbha region.

The Vakatakas and their Grant at Chammak Village

Following the decline of the Satavahanas, the Vakataka dynasty emerged as the principal power in the region during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. Their dominion covered large portions of Berar, including Amravati district. The dynasty’s rulers maintained close alliances with the Guptas and were known for their patronage of Vedic learning and temple architecture.

The capital of the Vakatakas is believed to have been located at Bhandak (near Chandrapur), but their influence is confirmed through a copper-plate grant of Pravarasena II discovered at Chammak village (which lies in the Achalpur taluka of Amravati district). This grant establishes the Vakataka presence in the Amravati region and situates the district firmly within the network of Gupta-era polities.

Ellichpur as an Administrative Centre

Around 550 CE, the Chalukyas of Badami rose to power in the western Deccan and gradually extended their control northward into Berar. Pulakeshin I and his successors established administrative centres and built connections with existing trade routes.

In the mid-8th century, the Chalukyas were overthrown by Dantidurga, founder of the Rashtrakuta Empire. Under the Rashtrakutas, Amravati was incorporated into its wider administrative framework. The city of Ellichpur (present-day Achalpur), located within the district, served as a provincial headquarters. Rashtrakuta rule over the region continued until 973 CE and is remembered for its contributions to temple architecture and literary culture.

After the fall of the Rashtrakutas, Taila II revived the Chalukya dynasty under the Kalyani branch. The Godavari River briefly served as a frontier between the Chalukyas and the Paramaras of Malwa, during a period of military conflict. Although Berar was temporarily held by the Paramaras, Taila II succeeded in reasserting Chalukya control by the close of the 10th century.

By the late 12th century, the Chalukyas had declined, and the Yadavas of Devagiri had risen to prominence. Under King Singhana, much of Vidarbha, including Amravati, came under their authority. The district of Amravati seems to have held much administrative importance during this period. Chroniclers like Barani and Ferishta record that Ellichpur was among the prominent provincial capitals under the Yadava rulers. This period marked the end of what might be termed the ancient era of Amravati, as the region entered a new phase of military contest and political realignment during the 14th century.

Medieval Period

Delhi Sultanate

Amravati, encompassing its expansive domain, possessed a wealth of resources in terms of its economy, military significance, and strategic importance. This abundance had attracted various powers to engage in fierce conflicts for its possession.

From the late 1200s, the expansion of the Delhi Sultanates in the region led to a series of recurrent incursions, culminating in the establishment of a vassalage in Deccan by emperor Alauddin Khilji. In 1296, Alauddin, who was the son-in-law of the ruling emperor Jalal ud-din Firoz Shah Khilji, independently advanced to the Deccan region. During this period, the ruling authority governing Amravati was held by the Yadavs of Devagiri. Although the territory was not annexed, substantial treasures were seized, including from Achalpur that lay within Amravati. Alauddin was stationed at Achalpur for two days before he expanded his raid to nearby areas. Highlighting the unprecedented external intervention and the vast wealth accumulated by him, the medieval chronicler Ziauddin Barani observed that:

“The people of that country had never heard of the Musulman; the Maratha land had never been punished by their armies; no Musulman king or prince had penetrated so far. Deogir was exceedingly rich in gold and silver, jewels and pearls and other valuables…On the first day he took thirty elephants and some thousand horses. Ram-deo came in and made his submission. Alauddin carried off an unprecedented amount of booty.”

The accumulated wealth was so substantial that, according to Barani, it endured until the era of Firoz Shah Tughlaq. Enchanted by the riches of Devagiri (present Daulatabad in Aurangabad district), Alauddin was determined to annex the territory. Around 1306, the second expedition to Devagiri was carried out under the leadership of Alauddin’s commander, Malik Kafur. With the pretext that the reigning king Ramachandra had halted tribute payments to the Sultan, Malik Kafur advanced to Devagiri. Subsequently, along with Devagiri, Amravati was integrated into the Sultanate's realm.

After the death of Alauddin, Harpal, son-in-law of the king Ramachandra, for a brief period, reclaimed the region including Amravati, from the control of the Sultanate.

Bahmani Sultanate

The rise of the Bahmanis posed a challenge to Delhi's dominance in the Deccan region. The formation of the Bahmani Sultanate (1347) marked the breakaway of the Deccan from Delhi Sultanate control. This new Deccan-based kingdom expanded into the surrounding regions — including Berar, where Amravati was a key province.

After Alauddin Bahman Shah (Hasan Gangu) founded the Bahmani Sultanate, the Berar region (including Amravati) became part of the new power structure. Eventually, Berar emerged as one of the five provinces (tarafs) of the Bahmani kingdom. Over time, Berar became a separate Bahmani province. During the rule of the Bahmani Sultanate, Achalpur (formerly Ellichpur) emerged as a prominent administrative and military centre in the northern part of Berar. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1911), Ellichpur served as the headquarters of the tarafdar (provincial governor) of Berar, whose jurisdiction extended well beyond the limits of the present-day district—reaching the Godavari in the south and beyond Baitelwadi in the west.

The tarafdar operated with considerable autonomy. He commanded provincial forces, collected revenues, and appointed key officials, including fort commanders. His main obligations to the Bahmani central government were to forward a share of revenue and provide military support when summoned. The region was effectively governed as a semi-independent province.

To consolidate northern control and respond to regional disturbances—particularly in areas where local rulers and the Gonds had gained ground—the Bahmani ruler Ahmad Shah Wali marched north in 1425 CE. He spent nearly a year at Achalpur, reinforcing its role as the administrative and military headquarters of the northern province. During this campaign, he fortified the Gawilgad Fort in the Satpuda range and is also believed to have repaired the Narnala Fort, both located within present-day Amravati district.

The fort at Gawilgad, believed to have earlier origins tied to the Gawli (cowherd) community, was extensively rebuilt by the Bahmanis. Its name is thought to derive from these pastoralist communities who had long inhabited the Berar region.

Achalpur as the Capital of the Imad Shahi dynasty

Following the decline of central Bahmani authority, Berar emerged as an independent sultanate under Fateh-ullah Imad-ul-Mulk, the former governor of the province. Around the early 16th century, he declared his independence and established the Imad Shahi dynasty, choosing Achalpur (Ellichpur) as the capital of the new state. The city retained its earlier role as a political and military hub, overseeing the administration of the Berar region.

One of Imad-ul-Mulk’s most enduring architectural contributions was the strengthening of the Gawilgad Fort, which continued to serve as the principal fortress of the northern plateau. As a symbolic assertion of sovereignty, he is said to have adorned the Delhi Gate of the fort with carvings of the ganda-bherunda—a two-headed bird emblem borrowed from the emblems of the Vijayanagara Empire. This act possibly served to legitimize the new dynasty through visual claims of strength and continuity.

The importance of Gawilgad is further affirmed by the Mughal chronicler Abul Fazl, who in the Ain-i-Akbari describes it as “a fortress of almost matchless strength. In it is a spring at which they water weapons of steel.” Its formidable construction, elevated location, and secure water sources made it one of the strongest hill forts in the Deccan.

During the early 17th century, Berar became the subject of competing claims by the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and the Mughal Empire. After a series of conflicts and negotiations, the region was formally annexed to the Mughal dominion in 1595, under Akbar, when Chand Bibi, acting as regent of Ahmadnagar, ceded it to the empire.

Ahmadnagar Sultanate and the Annexation of Berar

By the mid-16th century, the Imad Shahi dynasty of Berar had weakened under internal power struggles. The effective control of the state had passed into the hands of Tufail Khan, a powerful noble who acted as regent, while the reigning Sultan of the time Burhan Imad Shah was reduced to a nominal figurehead.

In 1572, Murtaza Nizam Shah I of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate launched an expedition into Berar. While the declared purpose was to rescue Burhan Imad Shah from Tufail Khan’s control, the actual aim was the annexation of Berar. The Ahmadnagar forces, which included both African and foreign mercenary troops, engaged in a series of military confrontations with the forces of Tufail Khan and his son Shamshir-ul-Mulk. Despite resistance, Berar was eventually subdued, and the Imad Shahi dynasty came to an end.

With the incorporation of Berar, Ellichpur (Achalpur)—formerly the capital of the Imad Shahis—was brought under Ahmadnagar's rule. The province was then reorganised administratively. Prominent nobles of Ahmadnagar, including Khudiwand Khan and Khurshid Khan, were appointed to oversee the newly acquired territories. This restructuring displaced former elites and generated widespread unrest, as loyalties to the deposed dynasty persisted in parts of the region. The transition was marked by conflict and rebellion, and Ahmadnagar’s hold over Berar remained contested for several decades.

Ahmadnagar’s control over the Amravati region, part of northern Berar, continued until the end of the 16th century. In 1595, amid the growing pressure of Mughal expansion, the regent of Ahmadnagar, Chand Bibi, formally ceded Berar to the Mughal Empire as part of a political settlement during Emperor Akbar’s reign. Despite this, actual control remained in dispute for a few more years.

In 1598, after a series of campaigns, Mughal forces captured key forts in the region, including Gawilgarh and Narnala, both located in or near present-day Amravati district. These strongholds had strategic importance, and their capture marked the end of Ahmadnagar’s authority in northern Berar.

Mughal and Maratha Rule

For the Mughals, Berar's annexation was more than a territorial conquest. It was an opportunity to shape the empire's narrative. Berar was more than a landmass; it held stories, resources, and a unique identity of its own. Akbar decided to integrate a comprehensive record of Berar in the Ain-i-Akbari during 1596-97, highlighting its significance in governance, resources, culture, and its role within the empire's administrative structure.

Ain-i-Akbari indicates that Berar Subah (or province) was administratively divided into 13 sequential revenue districts, Amravati being encompassed in Sarkar of Kallam (present Kalamb town in Dharshiv). Highlighting the inherent richness of the province and its remarkable capacity to yield productive crops, Abul Fazl observes that, “the climate and cultivation practices within this province are remarkably good.”

However, the region continued to face renewed hostilities and new threats from the emergence of Maratha powers, Nizam Shahs, and the East India Company later on. In 1634 Shahjahan reorganized the region. During Shah Jahan's administrative reforms, there was a major reorganization of Mughal territories in the Deccan. Earlier, Khandesh, Berar, and parts of the Ahmadnagar territory were all governed together as one province, usually from Burhanpur. But Shahjahan decided to restructure this arrangement. He shifted some areas south of the Narmada River from Malwa into Khandesh and Berar, and then divided the entire region into two parts: Balaghat (southern division) and Payanghat (northern division).

This division effectively split the old Berar province, with the dividing line running roughly from Rohankhed in the west to Siwargaon on the Wardha River in the east. As a result, Amravati District came under the Payanghat division, which was governed by Khan-i-Daurin, while Sipahdar Khan was stationed at Ellichpur under his authority.

Shahjahan made another administrative reorganization in 1636, just two years after the earlier reorganization of 1634. Now, the Mughal Deccan territories were formally divided into four separate subahs (provinces):

Daulatabad and Ahmadnagar – administrative center was Daulatabad, but Aurangzeb resided at Khirki (renamed Aurangabad).

- Telingana – including Mughal-conquered areas of north-western Telangana.

- Khandesh – administrative capital was Burhanpur, with Asirgarh as the main military post.

- Berar – capital was Ellichpur, and Gawilgarh fort nearby was an important stronghold.

This clearly shows that Berar, including Amravati, was fully formalized as a separate subah (province) under Mughal rule, with its own governor (Khan-i-Dauran) and a deputy governor (Sipahdar Khan) stationed at Ellichpur.

Aurangzeb became the Mughal emperor in 1658 after a war of succession following the death of his father, Shah Jahan. Aurangzeb’s rule extended over a vast empire, and his focus on the Deccan and conflicts with Chhatrapati Shivaji (founder of the Maratha Empire) and other Deccan sultans became prominent in the latter half of the 17th century, particularly during the 1660s and 1670s. Simultaneously, Chhatrapati Shivaji ascended to prominence in the Deccan, notably in the 1640s and 1650s, when he claimed several forts and paved the way for the establishment of his Maratha kingdom. Upon his coronation as Chhatrapati in 1674, Shivaji had already become a substantial regional power.

During this period, a protracted conflict unfolded between the Mughals and the Marathas in Deccan including Berar, spanning the years from 1680 to 1707. Amidst these hostilities, Achalpur, serving as a provincial seat of power, must have witnessed its fair share of turmoil. However, with the demise of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire began to experience a gradual decline.

Marathas

Berar—including the present-day Amravati district —continued to face conflict and instability even under Mughal rule in the late 17th century, as Maratha power was rising and Mughal authority was under strain. In 1699, during the later years of Aurangzeb's reign, the Marathas under Rajaram, the younger brother of Sambhaji, invaded Berar with the aim of capturing the province. Rajaram, who had been a fugitive from Mughal forces after his brother’s execution, gathered a large army and entered Berar, following the usual Maratha pattern of plunder and destruction—raiding, burning villages, and disrupting administration.

He also gained support from Bakht Buland, the Gond Raja of Deogarh, who had earlier been part of their court but was not fully loyal to the Mughal empire. In response, Bedar Bakht, son of Prince Muhammad Azam, was sent by Aurangzeb to suppress the Maratha raids. He succeeded in driving Rajaram and his forces out of Berar, at least temporarily.

Under the astute leadership of Maratha Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath, the Maratha’s claims to Chauth and Sardeshmukh were also recognised under Farrukhsiyar. In the Maratha administration, the position of the Peshwa is second only to that of the king. After 1707, Berar was one of the provinces where Marathas gained governorship and collected Chauth and Sardeshmukh which were sources of tax revenue for the kingdom. Chauth was an annual tax nominally levied at 25% on revenue or produce on lands that were under nominal Mughal rule. The Sardeshmukhi was an additional 10% levy on top of the Chauth as a tribute paid to the king.

In the early 18th century, the Marathas, under the leadership of Chhatrapati Shivaji’s grandson Shahu Maharaj, regained their power and claimed vast territorial expanse. On 9th October 1722, after his return from Mughal captivity, Shahuji took a momentous decision. He granted the territories of 43 villages, including Amravati and Badnera (both in Amravati district), to Shri Ranoji Bhosale. This act of bestowing these lands upon Bhosale was a significant chapter in the district’s history, further solidifying the Bhosale legacy in the district and marking the course of its development in the years to come.

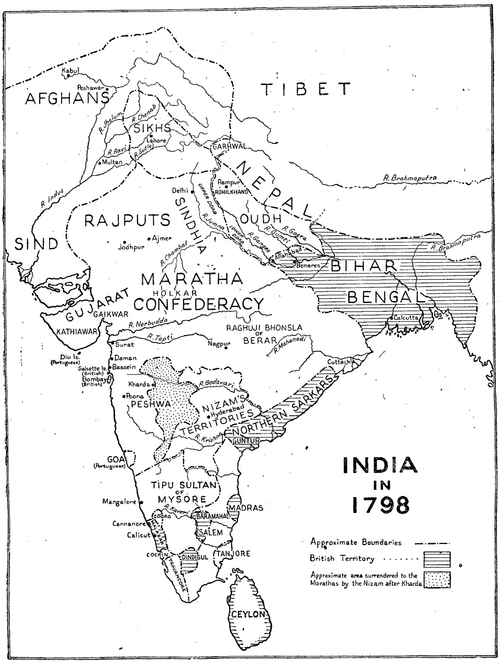

The emergence of the Nizams of Hyderabad in 1724 and their claim to Berar resulted in both of these formidable powers engaging in internecine warfare, further ravaging the already tumultuous region. In 1795, the Battle of Kharda, occurred between the Nizams of Hyderabad and the Maratha Confederacy, resulting in the defeat of the Nizam. Following the conflict, the treaty stipulated that Berar, initially relinquished to the Nizam, was restored to the Marathas.

Raghoji I Bhosale

The Bhosale dynasty of Nagpur, a powerful Maratha ruling family, played a crucial role in shaping the political, military, and cultural landscape of the Vidarbha region, including Amravati. Their influence evolved over several decades, particularly under the leadership of Raghoji I Bhosale, who founded the dynasty’s rule in the early 18th century.

The Marathas, under Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, had already established dominance in western Maharashtra by the late 17th century. However, Vidarbha, including Amravati, was under the control of the Mughals and the Gond kingdoms during this period. It was Raghoji I Bhosale, originally a Maratha general under Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, who expanded Maratha influence into Berar (modern-day Vidarbha) and Central India by the early 18th century. Around 1734, Raghoji I Bhosale took control of Nagpur and made it his capital, marking the beginning of Maratha rule over Vidarbha, including Amravati.

Amravati was strategically located along trade routes and fertile lands, making it an important administrative and economic center. As part of his broader military campaigns, Raghoji I Bhosale annexed Amravati and the surrounding areas from local rulers, integrating them into his growing kingdom. The Marathas used Amravati as a regional administrative center and a military outpost, strengthening their control over the region.

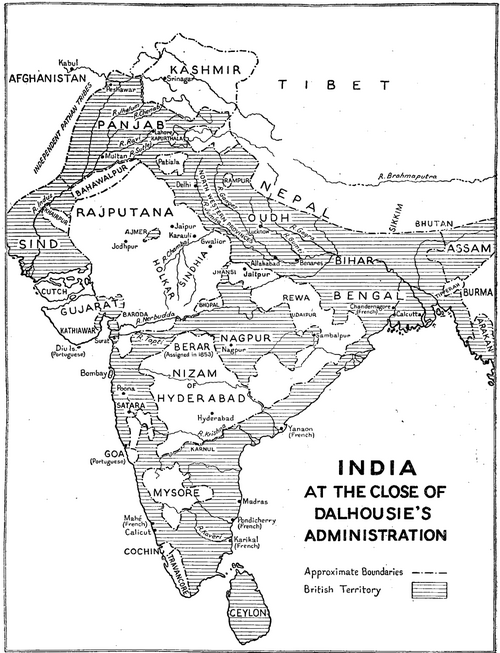

The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) led to the defeat of the Nagpur Bhosales, including their forces in Amravati. The British annexed Amravati and surrounding areas, incorporating them into the Berar province, officially ending Maratha rule in the region.

Maratha Revenue System

The Bhosales introduced the Maratha revenue system (Chauth and Sardeshmukhi taxes), which replaced Mughal revenue policies in the region. Amravati became a part of the Nagpur Bhosale’s revenue and governance structure, contributing to the economic framework of the empire. Local zamindars and village headmen were integrated into the Maratha administration, ensuring better control over tax collection and law enforcement.

Colonial Period

Berar, including the district of Amravati, experienced a profound administrative transformation during the rule of the British East India Company. This period marked a pivotal shift in the governance and structure of the region, shaping its destiny in ways that continue to influence the present-day administrative landscape.

In 1724, Asaf Jah, who had previously served as a Mughal official in the Deccan, sought independence by establishing an autonomous Nizam lineage in Hyderabad and began asserting his claim over Berar. In his quest to expand his territorial control in Berar, he formed an alliance with the British and, through a series of battles and treaties, successfully acquired Berar in 1804 (the Second Anglo-Maratha war). British Major General Arthur Wellesley's victory in the battles of Assaye (present village in Jalna district) and Argaon (present village in Ratnagiri district) in 1803, compelled the Bhosale raja to relinquish his lands situated to the south of Gawilgad and Narnala Fort, as well as those on the eastern side of the Wardha River.

After the British victory in the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1805), the Nizam of Hyderabad received administrative control of the Berar province for nearly four decades, managing it as Hyderabad’s Assigned Districts. This arrangement did not last long. The modification of the arrangement in 1853, Amravati with the rest of Berar, was held in “trust” by the East India Company.

When the company took the “trusteeship” of Berar, the province was divided into two districts: South Berar with its headquarters at Hingoli (present Hingoli district) and North Berar with headquarters at Buldhana (present Buldhana district). The latter included Amravati District.

In 1903, the rule of the Nizam came to a close in this region. It marked a significant turning point in the historical landscape of Berar. The Nizam leased Berar to the British Government under the viceroyalty of Lord Curzon in perpetuity, in return for an annual rent of 25 lakhs. Thereafter, the governance of Berar was transferred from the Resident at Hyderabad to the Chief Commissioner of the Central Provinces. Then, in 1936, following the establishment of the legislative assembly for the Central Provinces and Berar, the region underwent a renaming. It was henceforth known as the Central Provinces and Berar, and Berar itself became recognized as the Berar Division that included present Amravati district.

Colonial Administrative Reorganization

Under British rule, especially after it came under the control of the British East India Company they made several administrative and territorial changes to better manage the region for revenue collection and governance: South Berar (Balaghat) — headquartered at Hingoli; North Berar (Payanghat) — headquartered at Buldana, and included Amravati, northern Akola, and part of Buldhana district.

After the 1857 Mutiny, Hingoli and its surrounding region were returned to the Nizam, and the province was reorganized into: East Berar with headquarters at Amravati; West Berar with headquarters at Akola.

Further changes happened over time:

- In 1864, Yavatmal District (initially called South-East Berar, later Wun District) was carved out of Amravati. In 1867, Ellichpur/Achalapur District was created, initially including Morsi taluk, which was later returned to Amravati.

- In 1903, a significant shift happened: the Treaties of Assignment were replaced by a perpetual lease agreement under which the Nizam leased Berar to the British Government in return for an annual rent of 25 lakhs. The administration was transferred from the Resident at Hyderabad to the Chief Commissioner of Central Provinces.

- In 1905, another reorganization took place: Ellichpur District was merged back into Amravati, and Murtizapur taluk was moved from Amravati to Akola.

Struggle for Independence

During the period of colonial rule, Amravati district became an active centre of political awakening and nationalist mobilisation. It was home to several prominent figures who contributed to India’s struggle for independence, including Ganesh Srikrishna Khaparde (popularly known as Dadasaheb Khaparde), Ranganath Pant Mudholkar, Sir Moropant Joshi, and Pralhad Pant Jog.

Among these, Dadasaheb Khaparde played a particularly influential role. A scholar of both Sanskrit and English, Khaparde held a degree in law and practised in Amravati. His political career developed in close association with leaders of the nationalist movement, especially Bal Gangadhar Tilak, with whom he maintained a longstanding relationship. In 1897, Khaparde served as chairman of the reception committee during the Amravati session of the Indian National Congress. Later, in 1916, he presided over the 18th session of the Bombay Provincial Conference held at Belgaum.

Khaparde was also closely associated with the Berar Sarvapakshiya Samiti, a political forum that opposed the merger of Berar with the Central Provinces under British administrative reforms. Representing the interests of the Marathi-speaking population, the Samiti petitioned Lord Montague, demanding the recognition of Berar as a separate sub-province. These efforts culminated in a formal resolution in 1933 to separate Berar from the Central Provinces. However, the onset of the Second World War delayed implementation, and political focus shifted towards larger national concerns. Still, Khaparde’s efforts, in many ways, reflect a strong commitment to preserving the cultural and linguistic identity of the Marathi-speaking population in the region.

Sant Tukdoji Maharaj

Tukdoji Maharaj made a significant contribution to India’s freedom movement through his patriotic bhajans, which awakened rural consciousness. He was born as Manik Namdeo Ingle in 1909 in Yavali village of Amravati district, Maharashtra, and was a sant, philosopher, and social reformer. The son of a poor tailor, he showed little interest in formal education and was drawn to devotional singing and playing the khanjiri. Under the guidance of his Guru, Shri Akdoji Maharaj of Varkhed, he was renamed “Tukdoji.” He spent years meditating in the forests of Ramtek, Salburdi, and Gondoda in pursuit of spiritual enlightenment (Atmadnyan).

In Amravati and nearby regions, Tukdoji Maharaj inspired people through his bhajans and spiritual discourses. He encouraged self-reliance, cleanliness, and village unity. He personally participated in building roads, promoting sanitation, and uplifting the moral and social life of the villagers. His simple, locally inspired songs became a medium for spreading values of brotherhood, devotion, and social service.

As a bachelor devoted to the welfare of humanity, Tukdoji Maharaj opposed the priesthood and promoted the belief that God exists everywhere, not just in mandirs. His unique prayer gathering system united people of all religions. Through his teachings, writings, and service, he became a true symbol of devotion, humility, and national unity. His work, Gramgita, became a guide for village development and moral living. He was admired by Mahatma Gandhi and represented India at the Vishwadharma Parishad in Japan in 1955, spreading India’s message of universal brotherhood.

Local Newspapers

The district in 1909 was an active center of nationalist journalism and resistance. The region had an intellectually vibrant and politically conscious population that used the press as a tool against colonial rule, making it a significant part of India’s struggle for freedom. However, in 1909, several newspapers from the district were deemed seditious by the British authorities due to their nationalist stance and criticism of colonial rule.

According to Archival sources, Kartavya, a weekly published in Amravati and edited by Nilkant Sakharam Bhangle, had a circulation of 600 copies and played a significant role in spreading anti-British sentiment. Similarly, Pramod Sindu, another weekly edited by Ramchandra Yeshwant Keskar, with 100 copies, and Prabhat, published from Ellichpur (Achalpur) city by Govinda Sitaram, also with 100 copies, contributed to the growing wave of resistance against British rule. These newspapers provided a platform for patriotic expression, exposing colonial injustices and advocating for self-rule. As a result, they were targeted under oppressive laws like the Vernacular Press Act and Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, which aimed to curb dissent. Despite restrictions, such publications played a crucial role in mobilizing public opinion and fueling the Indian independence movement.

Post-Independence

After India’s independence in 1947, the Central Provinces and Berar, with some territorial adjustments, were merged into the newly formed state of Madhya Pradesh. Amravati district, which had been part of the Berar region, thus became part of this new administrative setup.

However, this arrangement did not align with the cultural and linguistic identity of the predominantly Marathi-speaking population of Amravati and surrounding districts. There was growing public demand for these areas to be integrated into a Marathi-speaking state that reflected their language and cultural heritage.

In 1956, a major restructuring of Indian states took place based on linguistic lines under the States Reorganisation Act. As a result, the Berar and Nagpur divisions, including Amravati, were transferred from Madhya Pradesh to Bombay State.

Just a few years later, in 1960, Bombay State was bifurcated to form two new states — Maharashtra for Marathi speakers and Gujarat for Gujarati speakers. Since that reorganization, Amravati has remained an integral part of Maharashtra, situated within the larger Vidarbha region.

Sources

About the Mundy Map. Famine and Dearth in India and Britain 1550 - 1800: Connected Cultural Histories of Food Securities.https://famineanddearth.exeter.ac.uk/aboutth…

Alexander Dow. 1772.The History of Hindostan. Ed. 1, London.

Bal Kamble. 2018.Movement for Independent Vidarbha State. Vol. 8, Issue 11. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences.https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/2018/IJRS…

Bipan Chandra, Mridula Mukherjee, and Aditya Mukherjee. 1999.India After Independence 1947-2000.Penguin Books, New Delhi.

Eugen Hultzsch. 1925.Inscription of Ashoka. Vol. 1, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Gazetteer of India. 1960.Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Amravati District. Directorate of Government Print, Stationery and Publications, Maharashtra State.

Government of Maharashtra. 1968.Amravati District Gazetteer, Revised Edition. Govt. Press, Nagpur, India.

Government of Maharashtra. History. District Amravati, India.

J. A. B. Van Buitenen. 1981.The Mahabharata. Vol. 2. University of Chicago Press.

Jadunath Sarkar tr.. 1949.Ain-i-akbari Of Abul Fazl I Allami. Vol. 2, Ed. 2. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, I Park Streat, Calcutta.

Jadunath Sarkar. 1949.Ain-i-akbari Of Abul Fazl I Allami. Vol. 2, Ed. 2. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, India.

Kishori Saran Lal. 1950.History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad, India.

Krishna Mohan Ganguly tr.. 1883-96.The Mahabharata: Vana Parva. Book 3, Sec. 96-7.

M.S. Naravane. 2014.Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi, India.

National Archives of India. 1909. “Selection from the Native Newspapers Published in the Central Provinces for the Week Ending 31st July 1909.“

P. V. Jagadisa Ayyar. 1993.South Indian Shrines. Asian Educational Services, India.

Pranab Kumar Bhattacharyya. 2010.Historical geography of Madhya Pradesh: From Early Records. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Delhi, India.

Ramachandra Guha. 2008.India after Gandhi. Macmillan Publication, London.

S. V. Fitzgerald and A. E. Nelson eds. 1911.Central Provinces District Gazetteers Amraoti District. Vol. A. The Caxton Works, Frere Road.

Sailendra Sen. 2013.A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Ratna Sagar P. Limited, India.

Sarojini Regani. 1988.Nizam-British relations, 1724–1857. Concept Publishing Company, India.

Satish Chandra. 2004.Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526) - Part One. Har-Anand Publications, India.

Shyam Narayan Lal. 2019.Understanding Changes in the process of transfer of agrarian settlements in the Vidarbha Plain. Vol. 80. Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27192874.pdf

Stanley A. Wolpert. 1989.Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reform in the making of Modern India.Oxford University Press, India.

Sven Beckert. 2014.Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, United States.

The Economic Weekly. 1955.“The Reorganization of State: The Approach and Arrangements.”https://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/1955_7/4…

The Hindu. 2011.Rukmini’s Love For Krishna. Chennai, India.https://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-rev…

Thomas Haig. 1907.. The Pioneer Press, Allahabad, India.https://archive.org/details/historiclandmar0…

Uday S. Kulkarni. 2021.The Maratha Century: Vignettes and Anecdotes of the Maratha Empire. Mula Mutha Publishers, Pune.

Vettam Mani. 1975.Puranic encyclopaedia : a comprehensive dictionary with special reference to the epic and Puranic literature.* Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, India.

Websites Referred:Amravati District: Official Website, Wikipedia.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.