Contents

- Etymology

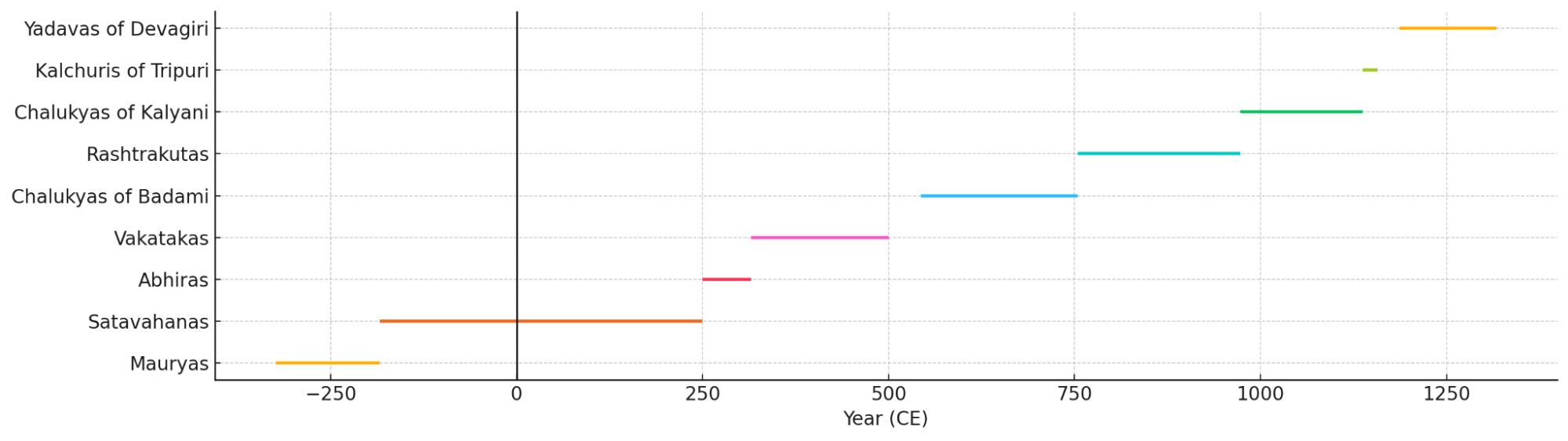

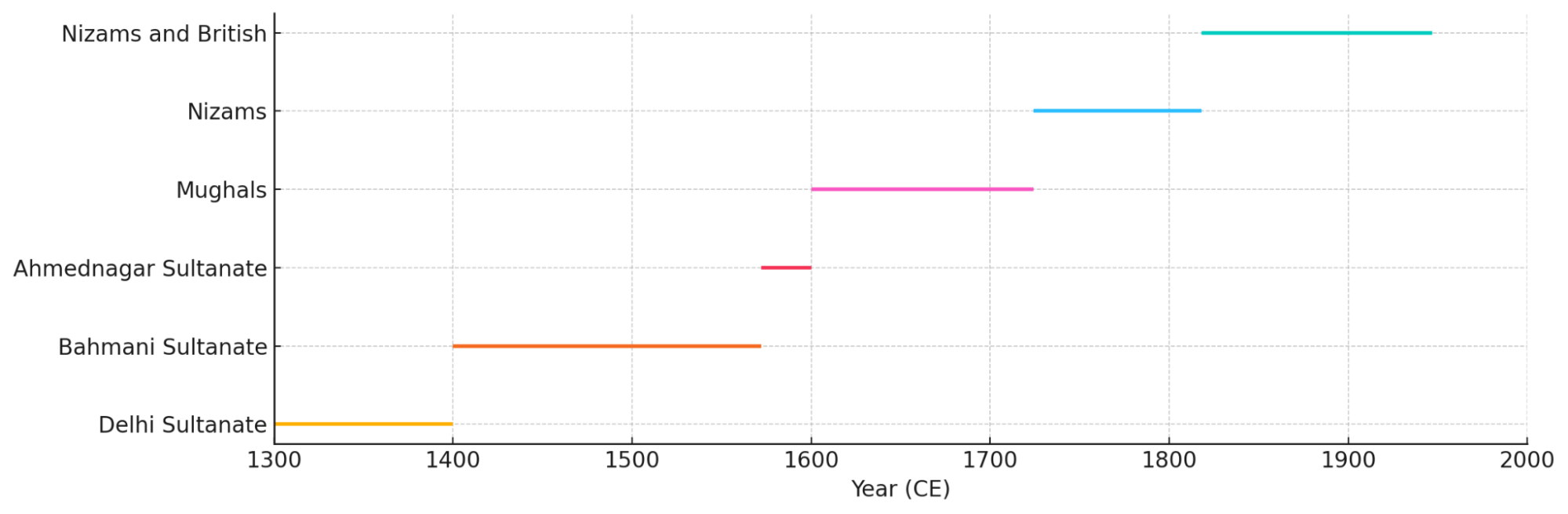

- Ancient Period

- Associations with the Ramayan

- Beed as part of the Sixteen Mahajanapads

- Rashtrakuta Presence and Inscriptions

- Yadava Rule and the Rise of Ambajogai

- Kholeswar Mandir

- Sakleshwar Mandir

- Kankaleshwar Mandir

- Mukundraj and the Literary Heritage of Ambajogai

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate

- Tughlaqs

- Muhammad bin Tughluq’s Lost Tooth

- Juna Khan and his Reforms

- Transition to Bahmani Rule

- The Battle near Kankaleshwar Mandir

- The Dhonde Raja of Ashti

- Mughal Rule in Beed

- Jama Masjid

- Sadar Shah and Urban Expansion in Beed

- A Hub for Chhagal Making

- The Maratha Offensive under Rajaram I

- Rise of the Nizam Shahis of Hyderabad

- Dharur Fort & Its Role in the Battle of Udgir

- Battle of Rakshasbhuvan, 1763

- Mahadji Scindia and the Sufi of Beed

- The Nizams of Hyderabad Under the British Paramountcy

- Dharmaji Pratap Rao’s Rebellion (1818)

- The Rang Rao Conspiracy (1858–1859)

- Early Reforms under the Fifth Nizam (1865–1866)

- Sant Bhagwan Baba

- Birth of Beed District (1883)

- Land Revenue System

- The Insurrection of Baba Saheb (1898–1899)

- The Great Famine of 1900

- Struggle for Freedom

- Cotton and Oil Seed Production

- Post-Independence

- Sources

BEED

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Beed, historically known as Bhir, is a district in central Maharashtra that lies along the banks of the Bindusara River, a tributary of the Godavari. The region has a long history, with local tradition holding that it was here where Jatayu, the eagle who is mentioned in the Ramayan, fell after attempting to prevent Ravan’s abduction of Sita.

Over the centuries, Beed came under the control of several dynasties and empires. In the 14th century, Beed came under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate, first under the Khilji dynasty and later under Muhammad bin Tughluq. Interestingly, a local legend from this time recounts that Tughluq lost a tooth in the region, and a tomb near the village of Karjani is associated with this story. The district later became part of the Hyderabad State under the Nizams of Hyderabad and remained so until it was integrated into India in 1948.

Etymology

The name of the district has changed several times over the centuries. According to local traditions, it is said that the region was known as Durgavati during the epic period and was later renamed Balni. Later, the area came to be known as Campavatinagar, and there is a very interesting story behind it. It is said to have been named by Champavati, sister of Vikramaditya of Ujjain, after she seized control of the region.

In the 14th century, during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the town was renamed Bir, as recorded in the historical text Tarikh-e-Bir. The name is believed to derive from the Arabic word bi’r (well), referring to the region’s shallow groundwater. Tughluq is said to have built a fort and several wells, which may have inspired the new name. Over time, the name evolved phonetically into Beed. An alternative theory, noted in the district Gazetteer (1960), suggests that the name Beed may derive from the word Beel, meaning a hole or depression, possibly in reference to the town’s geographical location at the base of the Balaghat range.

Ancient Period

The region now forming Beed district has, over time, fallen under the influence of different political and cultural powers. Although much of Beed’s early history remains unknown, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These traces are best understood in the context of the wider Deccan and Marathwada regions, with which Beed has long shared geographic, political, and cultural ties.

Associations with the Ramayan

One of the earliest accounts linked to Beed’s early history is tied to the Ramayan, lending the region a sense of antiquity. In the Aranya Kanda, i.e., the Book III of the epic, there is an episode in which Jatayu, the eagle king (Gradhraraja), attempts to rescue Sita from Ravan as he carries her toward Lanka.

As the story goes, Jatayu valiantly attempts to stop him, and in the ensuing battle, Ravan severs Jatayu’s wings. Gravely wounded, Jatayu remains alive long enough to inform Ram of Sita’s abduction.

Many locals believe that this episode occurred in the present-day Beed region. The Jatashankar Mandir, located in Bhandar Galli in Beed town, is traditionally regarded as the place where Jatayu drew his last breath. Although the epic does not name a specific location, this identification has persisted through oral transmission. The Mandir remains a site of cultural importance and is often cited in connection with Beed’s early history.

Beed as part of the Sixteen Mahajanapads

The early political history of Beed district is difficult to reconstruct, as little is known about it. However, when considered within the broader territorial and administrative shifts of the Deccan, a general outline can be drawn. Its history likely has been shaped by its location within larger territorial units of the Deccan, which, according to the Beed District Gazetteer (1969), “was then divided into several countries known by different names.”

It is described in the District Gazetteer (1969) that Beed was once part of Asmaka, one of the sixteen Mahajanapads referenced in ancient Buddhist texts, which is believed to have encompassed parts of modern-day Ahilyanagar and Beed. Later, Beed is said to have become part of Kuntala, a larger territorial-cultural unit that stretched across northern Karnataka and southern Maharashtra.

During the 3rd century BCE, the Mauryas were among the dominant powers whose influence extended into the Deccan under the reign of Emperor Ashoka. Following their decline, the Satavahanas established control over much of the Deccan. With Pratishthana (which lies nearby in Sambhaji Nagar) as their capital, their influence likely extended into Beed district. The Gazetteer notes: “The Bid district was undoubtedly included in the dominion of Satakarni I,” suggesting a clear incorporation into the early Satavahana realm. The Satavahanas ruled with the support of local chieftains known as Maharathis, some of whom may have governed Beed as feudatories.

By the 3rd century CE, the Abhiras, under Ishwarsena, succeeded the Satavahanas in some parts of Maharashtra. Inscriptions found in Nashik point to their control of western Maharashtra, and their presence may have extended into the former Asmaka region, possibly reaching Beed.

Around the same time, the Vakatakas, a major dynasty of central India, rose to prominence in Vidarbha. From the 3rd to 5th centuries CE, the Beed region likely came under their wider influence. It is suggested in the Gazetteer (1969) that they “may have conquered the northern part of Kuntala comprising Poona, Ahmadnagar, Satara, Solapur, Bid, and some other districts.” Their presence in Washim, Bhandak (Chandrapur district), and Sambhaji Nagar, as evidenced in their role in Ajanta Caves, suggests that their authority or influence plausibly extended into Beed’s territory.

The Chalukyas of Badami rose to power in the mid-6th century. During the reign of Pulakesin II, they are said to have annexed Asmaka, which likely included parts of modern Beed.

Rashtrakuta Presence and Inscriptions

Following the decline of the Chalukyas of Badami, the Rashtrakutas rose to prominence in the Deccan during the mid-8th century CE. Their influence over Beed is well attested through epigraphic records, and a significant copper-plate inscription issued by the Rashtrakuta emperor Govinda III in 806 CE was discovered in Dharur, which lies within the present-day Beed district. This grant mentions the donation of land in several villages, such as Avasgaon and Dhanegaon.

Further inscriptions, cited in the Beed District Gazetteer (1969), have been found in Ambajogai. It notes that “one inscription of the time of Rastrakuta king Mahdmandalesvar Udayaditya, dated in Saka 1066, speaks of the grant of the villages of Sailu, Kumbhephal, Javalganv, and a few others by the king to the Siva temple.” These epigraphs highlight both the territorial extent of Rashtrakuta governance and their patronage of religious institutions.

In the late 10th century, the Later Chalukyas of Kalyani regained prominence in the region. Beed likely remained part of their western Deccan territory. Their rule was briefly interrupted in the 12th century by the Kalachuris of Kalyani, who held sway over parts of the region during this period.

Yadava Rule and the Rise of Ambajogai

By the late 12th century, Beed came under the rule of the Seuna Yadavas, who ruled from Devagiri (modern Daulatabad). It appears that this period marked considerable prosperity for the region. It is noted in the District Gazetteer (1969), “In the Yogesvari Mahatmya, a reference to a certain Jain king by the name of Jaitrapala is to be found. The Yogesvari Mahatmya refers to him as a Yadava king. During the reign of Jaitrapala, Ambajogai enjoyed the status of a capital.” Under King Singhana, Yadava rule reached its zenith, and many significant monuments architecturally linked to them can be found in the region.

Kholeswar Mandir

The Kholeswar Mandir is located in the town of Ambajogai and is believed to be one of the oldest surviving mandirs in the area, which is tied to the Yadavas.

It is mentioned in the district Gazetteer (1969) that according to a Sanskrit inscription dated to Saka 1162, the mandir was commissioned by Laksmi, daughter of Kholesvar, a general under King Singhana. It was constructed in memory of her brother Rama, who had died in battle.

Sakleshwar Mandir

The Sakleshwar Mandir, also locally referred to as the Bara Khamba Mandir, is located on the outskirts of Ambajogai in Beed district. Dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv, the mandir is among the few surviving architectural remains linked to the Yadava period.

The earliest known reference to the Sakleshwar Mandir appears in a Nagari-script Sanskrit inscription dated to 1228 CE. The inscription records donations made by General Kholeshvara, a military commander under King Singhana. It identifies Kholeshvara as a patron of the Mandir and offers insight into the temple-building activity under Singhana’s reign.

The mandir is particularly known for its twelve intricately carved stone pillars, which support its outer sabha mandap and give the site its local name, Bara Khamba. Each pillar is detailed with ornamental carving, representing the high level of craftsmanship associated with Yadava-era architecture.

Kankaleshwar Mandir

Among the most well-known structures from the Yadava period in Beed district is the Kankaleshwar Mandir, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv. Situated in the heart of Beed town, the Mandir is distinct due to its architectural form and setting. Constructed entirely in black basalt, the Mandir stands at the center of a water reservoir, giving it a unique appearance that continues to draw much interest. Though the Mandir bears no surviving inscription, its stylistic features strongly suggest that it could have been built between the 10th and 12th centuries CE.

Mukundraj and the Literary Heritage of Ambajogai

Beed, more particularly Ambajogai, also holds much importance for its association with early Marathi literary figures. It is closely associated with Shri Mukundraj Maharaj, who is widely regarded as one of the first poets to write in Marathi. Today, his connection in the town is commemorated through a samadhi (memorial) that remains an important site for followers and literary enthusiasts alike.

Mukundraj is known for his seminal work Vivekasindhu, a text composed in a mix of Marathi and Sanskrit, which engages deeply with philosophical themes from the Advaita Vedanta tradition. Although debated, this text is believed by many scholars to be the first work of literature in Marathi language, written around the 12th century.

Medieval Period

Delhi Sultanate

By the late 13th century, the Yadava dynasty, which had ruled from Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district), faced increasing pressure from northern powers. In 1294, Alauddin Khilji led a military campaign into the Deccan during King Ramachandra’s absence in Gujarat. Exploiting this moment, Alauddin plundered Achalpur (Amravati district), forcing Ramachandra to retreat and eventually agree to a treaty. The Yadava king retained control but had to pay annual tribute and cede parts of his territory.

Later, in 1308, Ramachandra provided military assistance to Alauddin’s general, Malik Kafur, during campaigns in the south. However, this alliance was short-lived; by 1313, the Delhi Sultanate had annexed Devagiri, effectively ending Yadava rule. Malik Kafur assumed control of the Deccan, bringing regions like Beed under Delhi's authority.

Tughlaqs

After the Khiljis, the Tughlaq dynasty rose to power in Delhi. In 1327 CE, Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq famously shifted his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad (present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district), marking a significant turn for the Deccan region. According to the chronicler Ferishta, Beed district subsequently became a resting place en route for Muhammad bin Tughluq and his troops, and there was a distinct connection that they shared with the district.

Muhammad bin Tughluq’s Lost Tooth

An unusual incident from this period stands out. As recorded in the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), while travelling through Beed, Muhammad bin Tughluq lost one of his teeth near the village of Karjani (Beed district). The Sultan ordered a ceremonial burial for the tooth, and a tomb was built at the site to mark the event.

Today, the Tomb of the Tughluq’s Tooth still stands on a hill near Karjani. Remarkably, it is the only known resting place of Muhammad bin Tughluq’s remains outside of Delhi’s Tughlakabad. Unfortunately, the structure is now in a state of neglect and disrepair.

Juna Khan and his Reforms

During the first half of the 14th century, the Deccan governor Juna Khan is believed to have resided in Beed. His administration introduced several changes that reshaped the local geography and settlement pattern.

Among the most notable was the re-routing of the Bindusara (Bensura) river, shifting its flow from west to east, likely to protect the settlement from invasions and flooding; he also constructed a defensive wall on the eastern bank. These urban interventions resulted in the relocation of a significant part of the population to the western part of Beed, laying the foundation for the city’s later layout.

Transition to Bahmani Rule

In 1347 CE, Beed became part of the newly formed Bahmani Sultanate, established by Hasan Gangu, who declared independence from the Delhi Sultanate and took the title Alauddin Bahman Shah. Muhammad bin Tughluq attempted to suppress the rebellion and recaptured Daulatabad and the surrounding regions, including Beed. However, Gangu and his followers retreated to forts in Bidar and Gulbarga (both in present-day Karnataka).

As unrest continued in Gujarat, the Sultan withdrew. Imad-ul-Mulk was left in charge of the Deccan, but Gangu seized the opportunity, attacked Daulatabad again, and reclaimed Beed for the Bahmani Sultanate.

Under Firuz Shah Bahmani (r. 1397–1422), Beed saw renewed development. However, conflict erupted during the reign of Humayun Shah Bahmani (also known as Jalim or “the cruel”), when his brother Hasan rebelled and took shelter in Beed, marking another significant chapter in the district's history.

The Battle near Kankaleshwar Mandir

A notable conflict tied to the rebellion occurred near the Kankaleshwar Mandir (present-day Momin Pura Road, Beed), where local jagirdar Habibullah Shah, who supported Hasan, clashed with Sultan Humayun Shah Bahmani.

According to the Beed District Gazetteer (1988), both sides suffered heavy casualties. Habibullah Shah was killed, and Hasan Shah was captured and executed. The confrontation, set near a prominent Mandir site, underscores how Beed’s local power structures were actively involved in regional politics and resistance. However, it also indicates that the battle would have left lasting impacts on the local populace. Perhaps, beyond the immediate loss of lives, such conflicts could have led to displacement, demographic shifts, and societal upheaval.

Following the Bahmanis’ decline, control of Beed passed successively to the Ahmadnagar Sultanate (Nizam Shahis) and the Bijapur Sultanate (Adil Shahis). The Nizam Shahis retained control until 1600 CE when they were defeated by the Mughals under the reign of Akbar.

The Dhonde Raja of Ashti

In the 16th century, the town of Ashti (Beed district) was granted as a jagir to the Dhonde Raja, possibly by the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. The Dhonde family, known for both their military service and administrative capabilities, was instrumental in transforming the rocky and barren landscape of Ashti into a thriving trade hub. They later supported the Maratha Empire, earning renown for their valor and loyalty.

Mughal Rule in Beed

In the 16th century CE, the Mughal Empire extended much control over many parts of the Deccan region after Emperor Akbar defeated the Nizam Shahi forces at Ahmadnagar Fort, ending the reign of Chand Bibi, regent of the Sultanate. They had a strong presence in Beed under Mughal control, and it appears to have remained so until the rise of the Marathas, which was strategically significant due to its location.

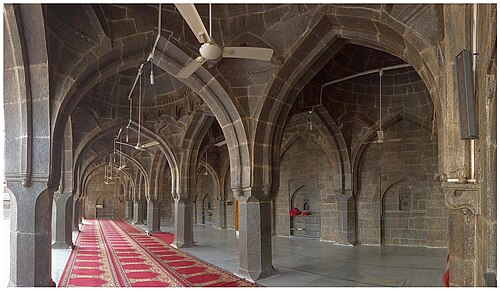

The district came under the administration of Jan Sipar Khan during the reign of Akbar’s son Jahangir (1569–1627), who is known for his contributions to art and culture. It was during his tenure that the Jama Masjid in Beed city was built in 1627.

Jama Masjid

The Jama Masjid is a prominent landmark in the district. It is one of the largest mosques, crafted entirely from stone with an impressive array of ten distinctive domes. Each dome boasts a unique design, creating an architectural masterpiece where no two domes mirror each other in form or style.

Sadar Shah and Urban Expansion in Beed

In the latter half of the 17th century, when Aurangzeb, before becoming the emperor, served as the Subhedar of the Deccan, he appointed Sadar Shah as Nayab Subba (Assistant Governor) of Beed. Under Sadar Shah’s leadership, the town underwent a significant urban transformation.

The historical chronicle, Tarikh-E-Bir (1989), records that in the year 1702, Sadar Shah laid the foundation for the Eid Gah, a sacred space for Eid prayers. He then developed a new residential quarter, Ghazi Pura (now Islam Pura), in 1703. He also restored and fortified the old Tughlaq-era fort, adding a citadel and leaving a Persian-inscribed stone plaque at the Jama Masjid to commemorate his efforts. Under his oversight, not only did the district gain in strength, but its economic prosperity flourished as well.

A Hub for Chhagal Making

Beed emerged as a regional center for skilled craftsmanship, particularly noted for the production of Chhagals, durable water containers crafted from animal hide, usually goat or sheep. These containers were designed to be both functional and portable, ideal for the arid climate and the needs of travelers, traders, and soldiers alike.

According to the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), Beed was historically recognized for this unique craft, with Chhagals being one of the town’s signature exports. The leather was specially treated and stitched to ensure durability and water resistance.

The Maratha Offensive under Rajaram I

While the Mughals maintained their hold on Beed for several years, it was soon challenged. After the execution of Sambhaji Maharaj in 1689, his younger brother, Chhatrapati Rajaram I, led the Maratha resurgence. In 1691, Rajaram launched campaigns targeting key Mughal outposts such as Jalna, Paithan, and Beed. The successful plundering of Beed weakened Mughal control and revitalized Maratha momentum in the region.

Rise of the Nizam Shahis of Hyderabad

By the early 18th century, Mughal authority was in steep decline. In 1724, Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, the Mughal governor of the Deccan, declared autonomy, founding the Asaf Jahi dynasty, the Nizams of Hyderabad. Beed came under the rule of this new polity and remained within the Hyderabad State until India's independence in 1947.

Throughout the 18th century, tensions simmered between the Nizams and the Marathas, resulting in multiple alliances and conflicts. While treaties were sometimes signed to divide spheres of influence, territorial disputes led to military clashes that reshaped the Deccan region’s political map.

Dharur Fort & Its Role in the Battle of Udgir

Dharur Fort is a hill fort located in the town of Dharur in Beed district. Positioned atop the Palghat Hills, the fort served as a military outpost through several historical periods and frequently changed hands during the political and military upheavals in the Deccan region.

The fort’s topography offered natural defenses, with steep valleys on three sides and a constructed moat (khandak) on the fourth, likely intended to deter frontal assaults. The terrain at the summit is relatively flat, and a double line of fortification appears to have been constructed to improve its defensibility.

It is said that the fort’s origins trace back to the ancient Rashtrakutas. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Dharur formed part of the Barid Shahi state, established by Qasim Barid during the disintegration of the Bahmani Sultanate. The Barid Shahi capital was at Bidar, and Dharur, along with Udgir, Ausa, and Kandahar, served as key military posts for the dynasty.

Surrounded by the rival Adil Shahi, Nizam Shahi, and Qutb Shahi states, the region saw frequent conflict. After the Barid Shahis lost control, the territory was contested mainly between the Adil Shahis of Bijapur and the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, during which it was reconstructed. Dharur later came under Mughal authority during their campaigns in the Deccan but was eventually absorbed into the Hyderabad State after the foundation of the Asaf Jahi dynasty in 1724.

The fort remained a secondary military post during the 18th century, particularly during periods of conflict between the Nizams and the Maratha Confederacy. One such conflict was the Battle of Udgir in 1760, during which it played a noteworthy role.

As the Maratha forces under Sadashivrao Bhau confronted the Nizam, a detachment of Nizam-aligned commanders, such as Sultanji Nimbalkar, Momin Khan, and Lakshmanrao Khandagale, attempted to march from Sambhaji Nagar with reinforcements. Intercepted by Maratha forces under Ranoji Gaikwad, they retreated into Dharur Fort, where they remained isolated and unable to support the Nizam’s main army. The subsequent Maratha victory at Udgir forced the Nizam to withdraw, with Dharur serving briefly as a point of retreat.

Dharur Fort remained under the Hyderabad State through the remainder of the 18th and 19th centuries, eventually becoming part of the Indian Union after Hyderabad’s integration in 1948.

Battle of Rakshasbhuvan, 1763

Another major engagement between the Marathas and the Nizam took place three years later at Rakshasbhuvan, a village in Georai taluka of Beed district near the Godavari River. In the battle, the Maratha forces were led by the young Peshwa Madhavrao I, supported by his uncle Raghunathrao, while the Nizam's army, commanded by Nizam Ali Khan, included key generals such as Vithal Sundar and Vinayak Dasrao. Notably, Vithal Sundar had previously served the Marathas before aligning with the Nizam.

The battle ended in a decisive Maratha victory, with Vithal Sundar killed and Nizam’s troops severely weakened. This victory helped the Marathas reassert authority in the region after their setback at Panipat (1761).

Mahadji Scindia and the Sufi of Beed

The aftermath of the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761 marked a turning point in Maratha history. Fought between the Maratha Confederacy and the Durrani Empire under Ahmad Shah Durrani, the battle ended in a devastating defeat for the Marathas and led to a period of political fragmentation and uncertainty across the confederacy.

One of the major Maratha figures injured in the battle was Mahadji Scindia, the influential ruler of Gwalior and a prominent leader within the Scindia dynasty. For a time following the battle, his condition and whereabouts were uncertain, giving rise to various accounts and local traditions concerning his recovery. According to local tradition in Beed, during this period of distress, Mahadji's wife, who is believed to have hailed from Beed, sought solace from Mansur Shah, a revered Sufi saint residing in the town. Desperate for news and healing, she entreated him to pray for her husband’s safe return.

In the weeks that followed, Mahadji is said to have made a remarkable recovery and returned to Gwalior. As a gesture of deep gratitude, he sent an invitation to Mansur Shah to visit his court. The saint, however, declined the invitation, choosing instead to send his son Habib Shah to represent him. Touched by the saint’s humility and the miracle that followed, Mahadji is believed to have continued expressing his gratitude throughout his life. Notably, it is believed that the tomb of Mansur Shah, located in the eastern part of Beed city, may have been constructed or patronized by the Scindias in his honor.

The Nizams of Hyderabad Under the British Paramountcy

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the political landscape of India was changing. The British East India Company had become highly influential, and many Indian princely states, including Hyderabad, entered into formal agreements with the British. In 1798, the Nizam of Hyderabad entered into a formal alliance with the British, known as the Subsidiary Alliance. This relationship allowed Hyderabad to remain an independent princely state within the British Empire, where it gained a semi-autonomous status. Notably, Hyderabad later became one of the largest princely states, and Beed remained part of its territory.

The Hyderabad State remained under the rule of the Nizams, but over time, the British came to influence areas such as foreign policy, defense, and finance. This growing British presence coincided with the decline of Maratha power; as a result, the political environment changed in several ways, and many tensions also followed. Many tensions followed. With this change, the Beed region, as part of the Hyderabad State, was gradually drawn into these broader shifts.

Dharmaji Pratap Rao’s Rebellion (1818)

The year 1818 marked a pivotal juncture in the history of the Deccan, for it witnessed the definitive downfall of the Maratha Confederacy and the consequent consolidation of British rule in the region. The fall of the Marathas ushered in a brief yet turbulent period of instability, which eventually gave rise to various localized uprisings and acts of resistance throughout the Deccan region (see Yavatmal & Nagpur). Notably, in 1818, Beed emerged as the focal point of what is widely considered to be the first coordinated instance of political unrest in the Marathwada region.

The rebellion was led by Dharmaji Pratap Rao, who is described as a longstanding adversary of the Nizam’s government. It is described in the District Gazetteer (1969) that to suppress the rebellion, a combined force of British officers and Nizam troops under Lieutenant John Sutherland was dispatched to Beed. Acting on intelligence, Sutherland launched a surprise assault on a fortified village on 31 July 1818. Despite heavy rain and difficult terrain, the village was surrounded and stormed with a small but organized force, and after intense fighting, Dharmaji and his brother were captured. The operation was aided by local support, notably from Nawab Muhammad Azim Khan, whose knowledge of the area proved critical.

Though the rebellion was ultimately suppressed, the incident remains significant, as it provides an early indication of political dissent in Beed during the early 19th century.

The Rang Rao Conspiracy (1858–1859)

Years later, in the wake of the 1857 Revolt, which is widely regarded as India’s first war of independence, continued discontent against British rule could be seen across various parts of India. The suppression of the revolt did not mark the end of resistance, as many parts of India, including the Deccan region, remained rife with political unrest. This discontent gave way to several localized uprisings, such as the Rang Rao Conspiracy, which occurred in Beed during the years 1858–1859.

In 1858, Rang Rao, a patwari (village official) from Talkhed in Beed district, emerged as the key figure behind a conspiracy to initiate a coordinated uprising in the region.

According to the district Gazetteer (1969), Rang Rao had travelled to the north to meet Nana Saheb Peshwa, one of the leaders of the 1857 uprising. He returned with proclamations and instructions urging local officials, soldiers, and community leaders in the Deccan to rise against British rule. For several months, he moved across villages in Nanded, Beed, and Aurangabad (now Sambhaji Nagar), attempting to recruit allies, raise funds, and mobilize fighters.

Despite his efforts, it is noted that due to logistical issues, lack of resources, and support from several local leaders declining to support the cause, his plan failed. By early 1859, British intelligence uncovered the conspiracy. Rang Rao and several of his associates were arrested. Tried for treason, Rang Rao was sentenced and exiled to the Andamans, where he died in 1860.

Early Reforms under the Fifth Nizam (1865–1866)

It is important to note that the Rang Rao Conspiracy took place against a backdrop of widespread volatility in the Hyderabad State. During the time of Nizam Nasir-ud-Daulah’s rule (1829–1857), Hyderabad State had been facing mounting financial pressures. To raise funds, the government turned to revenue farming. Under this system, the rights to collect land revenue were leased to private individuals, who, it is said in numerous instances, exercised their authority with little restraint. The prevalence of excessive demands and coercive practices by these contractors led to considerable hardship among the agrarian population. In the Beed District Gazetteer (1969), it is recorded that “the revenues of the State were farmed to contractors…the grossest oppressions prevailed.” It is likely that, being a part of the Hyderabad State, the farmers and locals of Beed were subject to the same extractive practices seen elsewhere.

In many areas, it is noted that these conditions gave rise to unrest. Protests broke out, law and order deteriorated, and the Nizam’s forces often failed to contain the chaos, prompting the British to step in militarily. Eventually, growing debts and disorder forced the Nizam to cede control of Berar, Dharashiv (then Osmanabad), and Raichur Doab to the British in 1853.

However, many administrative changes began to take shape following his reign. The fifth Nizam, Afzal-ud-Daulah (r. 1857–1869), introduced a series of reforms aimed at improving the efficiency of state governance. A major development that came was the shift from feudal to bureaucratic control, which replaced the earlier system of jagirdars with formally appointed Awwal Taluqdars (chief revenue officials). In 1865, Jivanji Ratanji assumed the position of the first collector of Beed, introducing a new era of governance.

The following year, in 1866, the system of tax payments was also changed. Farmers, who had previously paid their dues in kind (such as grain), were now required to pay in cash. This reform paved the way for the introduction of the Ryotwari system, where cultivators (ryots) were treated as individual taxpayers, responsible for paying the state directly.

Sant Bhagwan Baba

Sant Bhagwan Baba made a significant contribution to Maharashtra by leading a powerful social and spiritual awakening, particularly in the rural areas of Marathwada. He was born as Abaji Tubaji Sanap on July 29, 1896, in Supe Savargaon Ghat, Beed district, and became a prominent kirtankar (devotional orator) in the Warkari tradition. After receiving spiritual initiation from his gurus, including Gitebaba Dighulkar and Bankatswami Maharaj, he established his primary karmabhoomi at Bhagwangad, near Beed. This fort-shrine became the epicentre of his movement.

Bhagwan Baba's kirtans were a revolutionary blend of devotion and social reform. He used them to attack deep-rooted superstitions, caste discrimination, and blind faith. He championed the cause of education and self-reliance for the poor and downtrodden, giving the Warkari tradition a modern, activist direction. His simple, direct teachings on humanity, equality, and devotion earned him millions of followers. His samadhi is at Bhagwangad, which continues to be a major pilgrimage centre.

Birth of Beed District (1883)

In 1883, Beed was formally recognized as a district within Hyderabad State. This was part of a wider administrative reorganization led by Salar Jung, the prime minister of Hyderabad during the reign of Mir Mahbub Ali Khan, the sixth Nizam (1869–1911). The goal of this reform was to divide the state into manageable districts with a more standardized system of governance.

According to the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), the district covered 3,926 square miles of directly administered land, which was divided between Khalsa (state revenue land) and Sarf-i-Khas (private estate of the Nizam). The remainder comprised jagir estates managed by nobles and former Mughal officials. Of the principal talukas, Kaij, Ambajogai, Beed (then known as Bhir), and Patoda occupied parts of the Balaghat range, known for its relatively elevated terrain, while others lay in the lower plains.

The district’s administration was structured into three subdivisions, each managed by officials known as Talukdars. Of these, two, namely Ambajogai and Majalgaon, were administered by second talukdars, while the remaining subdivision, consisting of Gevrai, Patoda, and Ashti, was placed under a third talukdar.

The taluka of Bhir was directly administered by the First Talukdar, who also exercised general supervision and bore responsibility for the coordination of revenue administration, judicial matters, and general supervision throughout the district. At the taluka level, day-to-day functions, including revenue assessment, law and order, and petty civil disputes, were managed by Tahsildars.

Land Revenue System

As Beed’s administrative structure became more defined in the latter half of the 19th century, changes were also introduced in the way land revenue was assessed and collected. A significant early step in this direction was the shift to cash-based tax payments in 1866 (noted earlier), which laid the foundation for the Ryotwari system. Under this system, cultivators (ryots) were treated as direct taxpayers to the state, reducing the role of intermediaries such as jagirdars.

A preliminary land survey was undertaken in 1880 to estimate the extent and productivity of cultivable land. According to the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), the survey revealed that over 1,78,000 acres of farmland had not been previously recorded. This was 11% more land than earlier estimates had shown. As a result, it is recorded that the government increased the total land tax by Rs. 1.5 lakhs, or 13% more than before.

This was followed in 1889 by a comprehensive land revenue settlement, conducted a few years after the formal establishment of Beed district. The settlement was declared valid for a period of fifteen years and brought the district’s revenue assessment into conformity with those prevailing in Sambhaji Nagar (then Aurangabad) and the Berar Province. This framework formed the basis of Beed’s revenue system well into the early 20th century.

Under the revised classification, land was assessed under two categories; to quote from the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), “The average assessment on ‘dry ’ land being Rs. 1-8 (maximum Rs. 1-14, minimum R. 1), and on ‘wet’ land Rs. 5 (maximum Rs. 6, minimum Rs. 4).”

The Insurrection of Baba Saheb (1898–1899)

Toward the end of the 19th century, Beed district became the site of a notable episode of armed resistance. In 1898, a mysterious figure known variously as Baba Saheb, Rao Saheb, Vithal Chate, or Balwant Jagdamb emerged as the leader of a planned uprising.

Described in intelligence records and cited in the district Gazetteer (1969) as a well-educated Brahmin fluent in English, Urdu, Marathi, and Kannada, Baba Saheb had ties to Maratha Sardar families (Sardar being a title used by senior Maratha nobles). His campaign began with covert meetings in Hyderabad, where he discussed plans to initiate an armed revolt to “drive out the British” from the region.

With assistance from sympathetic state employees and local officials, Baba Saheb shifted his base to Beed. Staying at the residence of a district clerk, he gradually built a network of supporters across Beed, Sambhaji Nagar (then Aurangabad), and parts of Dharashiv (then Osmanabad).

Baba sought to mobilize rural discontent, drawing in village leaders and promising future jagirs and high positions once power changed hands. To finance the campaign, his followers carried out a series of dacoities (armed robberies), and small weapons were reportedly distributed. Reports mention the distribution of small arms and the preparation of uniforms, flags, and silver waist plates bearing revolutionary slogans.

Later, in April 1899, according to the district Gazetteer (1969), a confrontation between Baba’s followers and state forces ended in the deaths of several insurgents and the arrest of 60–70 participants. Baba escaped and was last seen in Amravati in 1902. His associates, some of whom were village patels or low-level officials, were tried and sentenced to prison.

The Great Famine of 1900

The closing years of the 19th century brought a severe crisis to the Deccan. From 1897 to 1899, the region received poor rainfall, which led to the Great Famine of 1900. The consequences were devastating: thousands of cattle perished, and many human lives were lost to starvation. Villages were emptied as large numbers of people migrated to nearby regions in search of food and work. The 1901 Census, as recorded in the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), noted a dramatic population decline of 1,50,464 in Beed district alone.

Struggle for Freedom

In the early decades of the 20th century, political developments in the rest of India began to influence events within Hyderabad State, including Beed district. The post-First World War period saw a rise in political awareness, participation, and activism. National movements such as the Khilafat agitation and the Civil Disobedience Movement resonated with the people of the Hyderabad State.

Beed played a role in this broader awakening. The 5th Session of the Maharashtra Conference, which focused on social reform in Hyderabad, was held in Beed, where Shri Manikchand Pahade of Sambhaji Nagar presided.

The formation of the Hyderabad State Congress in 1938 was another major development. Although it mirrored the rise of the Indian National Congress in British India, its progress was slowed by local opposition, particularly from the Razakars, a paramilitary group organized under the leadership of Bahadur Yar Jung, associated with the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen. The Razakars emerged as a powerful force in Hyderabad politics, advocating for the preservation of the state’s autonomy under the Nizam. This paramilitary force played a significant role in the complex political dynamics of the region during a crucial juncture in India's history.

Cotton and Oil Seed Production

Amidst these political and social changes, agriculture remained the backbone of Beed’s economy. Historical records show that cotton has long been the district’s principal crop. According to the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), cotton was grown in all talukas of the district, covering an area of 318 square miles. This widespread cultivation underscores its central role in shaping Beed’s agrarian structure and trade profile.

Alongside cotton, oilseeds were also a major crop, cultivated on 118 square miles of land. The prominence of these two crops points to a diversified agricultural system, one that supported local livelihoods and contributed to the region’s economic standing. The legacy of cotton cultivation, from the past to the present, stands as a testament to the agricultural contribution that has defined the district’s economic identity over the years.

Post-Independence

Following the end of British colonial rule in 1947, the future of Hyderabad State, which included the Beed district, remained unresolved. While the Indian subcontinent was partitioned into India and Pakistan under the Mountbatten Plan, the question of princely states like Hyderabad was left open. On 1 June 1947, British paramountcy over Hyderabad was officially withdrawn, leaving the Nizam of Hyderabad with the choice to accede to either India or Pakistan or to remain independent.

The Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, expressed an interest in pursuing independence. His position was further underscored during the Cripps Mission in 1942, when he is said to have declined to fully align with the Allied war effort, signaling his broader political aspirations. In the years following independence, Hyderabad's position became increasingly untenable, especially amid rising political unrest and communal tensions in several parts of the state, including Beed.

By 1948, the situation had escalated, and the Indian government initiated a military operation known as "Operation Polo", also referred to as the "Police Action," to integrate Hyderabad into the Indian Union. Subsequently, a plebiscite was conducted, revealing an overwhelming majority in favor of joining the Indian Union.

While the operation was swift, its aftermath was marked by significant disturbances. In 1948, the Pandit Sunderlal Committee conducted a fact-finding mission, documenting the impact of the “Police Action” in the region. Their report, though debated, recorded significant loss of life and various incidents that occurred in the aftermath.

In the midst of political uncertainty, institutional rebuilding began. In 1952, the Beed Nagar Palika (Municipal Council) was formally established, functioning under the then Hyderabad State (1948–1956). Infrastructure development was also prioritized. In 1949, the Bindusara Project was initiated to provide irrigation and drinking water to Beed and its surrounding villages. This project reached completion in 1956. In the same year, the Hyderabad state was dissolved and amalgamated with Andhra Pradesh until the state reorganization took place in 1960.

Following the linguistic reorganization of the state in 1960, the new district of Beed was formed, which became an integral part of the newly formed state of Maharashtra. The formation of the Beed Zilla Parishad (District Council) soon followed, replacing earlier municipal structures.

Sources

Arjun. 2022. Explore the Mysterious Centuries-Old Kankaleshwar Temple in Beed! Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8y0vFDBRx90

Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf. 2006. A Concise History of India (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bipan Chandra et al. 2008. India Since Independence. Penguin Books India.

Directorate of Census Operations, Maharashtra. 2011. District Census Handbook, Beed District. Part 12 A, Series 28.

Frontline. 2001. From the Sundarlal Report.https://frontline.thehindu.com/other/article…

Government of Maharashtra. 1969. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Bhir District. Directorate of Govt. Printing, Mumbai.

Lucien D. Benichou. 2000. From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938–1948. Orient Blackswan, India.

Motiram Aware. 2024. मो.तुघलकचे बीड कनेक्शन, जिल्हा इतिहास. YouTube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLF8wXDIQ3Q

Quazi M. Q. Bīri. 1898.Tārīkh e Bīr (History of Beed) (in Urdu).

Sarkar Express News Channel. 2021. Beed के इस निसर्गरम्य वातावरणमे है दिल्ली के Sultan Muhammad Tughlaq के दांत Teeth का मकबरा. YouTube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAe7wORatM8

V.N. Gurav; S.K. Khilare; P.N. Narkhede; B.M. Kausal; R.S. Kumbhar; G.D. Dhond; K.K. Chaudhari. 1988. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Beed District (Supplement).Gazetteers Department, Bombay.

W. W Hunter. 1909. Bhīr District. In the Imperial Gazetteer of India.Volume 8. Oxford, Clarendon Press.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

Waltraud Ernst and Biswamoy Pati. 2007. India's Princely States: People, Princes and Colonialism. Routledge.

Wikipedia, Beed District.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beed_district

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.