Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- The Caves of Sitamai Dongri and Early Human Settlement

- Iron Age Cultures in the Wainganga Valley

- Pauni as an Urban and Religious Centre

- Satavahana Rule and Economic Prosperity

- Western Kshatrapas and the Inscription of Mahakshatrapa Rupiamma

- Vakataka Dynasty and the Shift of their Capital to Padmapura

- Yadava Rule and Hemadpanthi Mandirs in Korambi and Pinglayee

- Medieval Period

- The Mughal Incursion into Garha and the Fate of Deogarh

- Jatba and the Rise of the Deogarh Kingdom

- Conflict with the Mughals

- Bakht Buland Shah and the Revival of the Deogarh Kingdom

- Decline of the Deogarh Kingdom and the Rise of Raghuji Bhosale I

- Internal Conflict Among the Marathas

- The Treaty of Deogaon and the British

- Pindari Raids and the Fortification of Pauni

- Appa Saheb’s Revolt and Resistance in Bhandara

- Colonial Period

- First War of Independence, 1857

- Formation of the Central Provinces

- Famines

- Local Political Dissent and Repression

- Quit India Movement and the Tumsar Smarak

- Post- Independence

- Sources

BHANDARA

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Bhandara district lies at the eastern limit of Maharashtra and forms a part of the Nagpur Division. It is bounded on the east by the State of Chhattisgarh and on the north by Madhya Pradesh, with which it has long maintained historical and geographical associations. Notably, the district has yielded evidence of human occupation from a very early period. Stone tools, pottery fragments, and traces of early settlement have been recorded at several locations. Among these, the site of Pauni, on the banks of the Wainganga River, is of particular antiquity. Excavations there have uncovered Buddhist stupas, gateways, and sculptural fragments, indicating the presence of a settled and religiously active community during the early centuries of the Common Era.

In the medieval period, the region formed part of the larger Gondwana tract and was brought under the rule of the Kalachuris of Ratanpur, with inscriptions under the reign of Jajalladeva hinting at their presence. The area later passed successively to the Mughals, the Bhosales of Nagpur, and to the British in the early 19th century. Under British administration, Bhandara was included within the Central Provinces and Berar, and following the reorganisation of Indian states in 1950, it was transferred to Bombay State. It has remained part of Maharashtra since the state's formation in 1960.

Etymology

The origin of the district’s name is generally believed to lie in the term Bhanara, which appears in an inscription dated to 1114 CE, found at Ratnapura (present-day Ratanpur, in Bilaspur district, Chhattisgarh). The inscription was issued during the reign of Jajalladeva, the fifth ruler of the Kalachuri line based at Ratnapura. This dynasty was a regional branch of the Kalachuris of Tripuri, who held greater political prominence in central India during this period.

The record states that the ruler received annual tribute or customary gifts from the chiefs of several mandalas (which are outlying territories owing varying degrees of allegiance). Among those listed are Kosala, Andhra Khimidi, Vairagara, Lanjika, Bhanara, Talahari, Dandakapura, Nandavali, and Kukkuta. The name Bhanara has been identified by scholars such as Dr. Georg Bühler and Dr. A. F. Kielhorn with the area comprising the present-day Bhandara district.

Ancient Period

The Caves of Sitamai Dongri and Early Human Settlement

The earliest traces of human activity in the present-day Bhandara district come from the prehistoric caves of Sitamai Dongri, which is located along the Bawanthadi River. Uncovered by the Archaeological Department of Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University, these caves are believed to be nearly 40,000 years old, making them among the oldest archaeological sites in the region.

The caves contain rock paintings rendered in reddish-brown, grey, and white pigments, featuring stylised human forms, animal figures, and geometric patterns. Scholars date these artworks to both the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods, suggesting a continuity of habitation and ritual expression over millennia.

What makes Sitamai Dongri particularly significant is its resemblance to cave sites in nearby Balaghat region of Madhya Pradesh, which all in all, points to a shared cultural sphere across the Wainganga-Bawanthadi basin in prehistoric times.

Iron Age Cultures in the Wainganga Valley

Moving forward in time, the Wainganga river valley, which cuts across Bhandara district from north to south, became a cradle for Iron Age habitation. Archaeological surveys have revealed that the region was densely occupied during the 2nd millennium BCE, marked by the presence of megalithic burials, early settlements, and ceramic assemblages.

Tilotha Khairi, a small village in Bhandara is among the first sites where vestiges of megalithic cultures were uncovered and the most significant discovery came in 1994, when the Archaeological Survey of India excavated parts of Pauni, unearthing remains of Early Iron Age culture. The finds included diagnostic pottery types such as Micaceous Red Ware, Black-on-Red Ware, and Black-and-Red Ware, which are typically associated with pre-Mauryan cultures across the Deccan.

Subsequent explorations recorded in the Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute identified additional Early Iron Age habitations at Katangdhara, Sasara, and Korambhi. These settlements, situated close to the Wainganga river and its tributaries, revealed not only ceramic remains but also evidence of permanent occupation. The discovery of multiple such sites, in many ways, establishes Bhandara as a significant region for studying the evolution of early agrarian and metallurgical communities in central India.

Pauni as an Urban and Religious Centre

The present-day Pauni seems to have remained important throughout the early history of the district. Even as the broader region passed under the influence of various political and cultural powers, Pauni itself remained an active centre of settlement. It is generally believed to have formed part of the Mauryan Empire, and archaeological findings confirm its occupation during this period.

It is important to note that by the 6th century BCE, the town of Pauni had begun to emerge as a major urban centre in eastern Vidarbha. Excavations carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) have revealed a fortified settlement at the site. Thick ramparts and habitation layers have been dated to the pre-Mauryan period (6th–3rd centuries BCE). Archaeologist SB Deo contends that the fortifications appear to have been strengthened under the Mauryas, likely to secure access to trade routes and natural resources in the surrounding region.

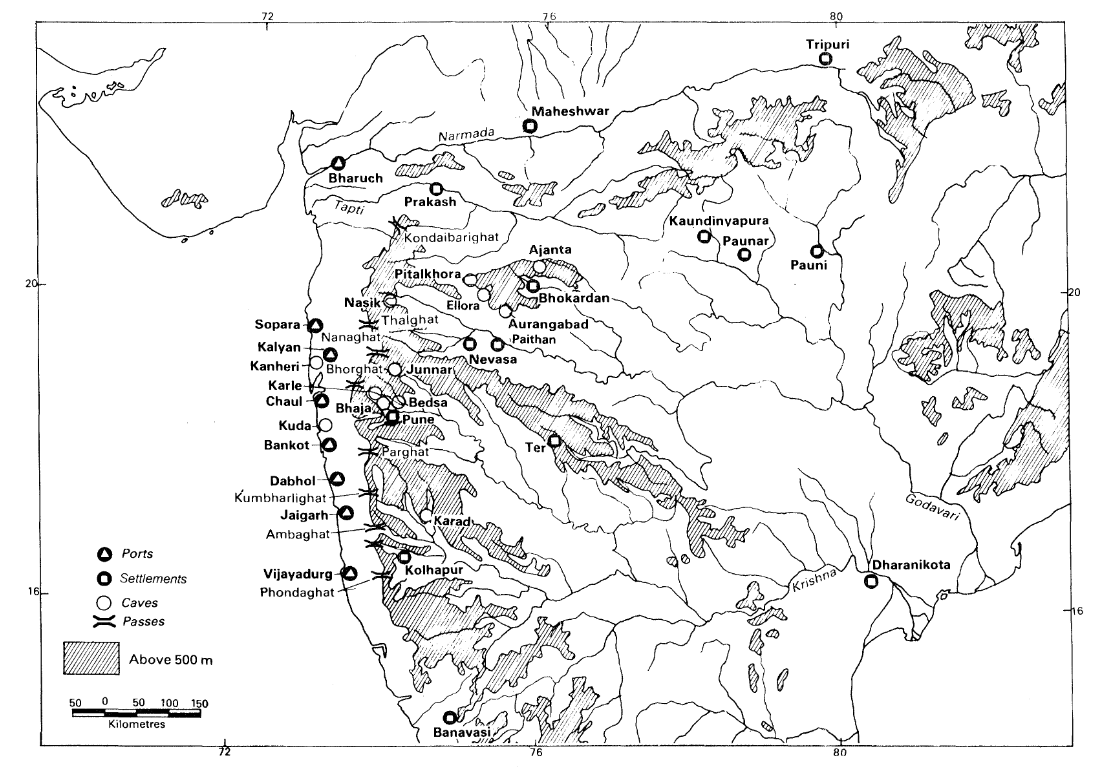

This early urban growth was closely linked to Pauni’s location. Positioned at the intersection of routes connecting the Narmada valley, the Wainganga basin, and the eastern Deccan, the town occupied a key point along regional trade networks. Its strategic placement not only enabled commercial expansion but also contributed to the rise of religious institutions. As Deo observes, “the strategic location of Pauni and better resource management of the transpeninsular trade route led to the establishment of the first Buddhist order in the entire Wardha–Wainganga divide.”

Notably, during the early centuries BCE, the town also emerged as a prominent Buddhist centre. Excavations unearthed three prominent mounds, Jagannatha Tekdi, Chandakapur Tekdi, and Hardolala Tekdi, of which the first two were confirmed as Buddhist stupa sites.

At Jagannatha Tekdi, remarkably, three major occupational layers were uncovered. The earliest, dated to the 4th–3rd century BCE, contained Northern Black Polished Ware and punch-marked coins. The second phase, associated with the Maurya–Shunga period (3rd–1st century BCE), revealed additional pottery types, inscriptions in early Brahmi script, and fragments of Shunga-era sculptures. Structural remains included parts of the stupa’s boundary wall (pradakshina patha) and gateway bases. These remains, in many ways, suggest that Pauni served as a significant Buddhist centre through both the Maurya and Shunga periods.

Satavahana Rule and Economic Prosperity

After the decline of Mauryan authority, control over the wider Vidarbha region, where Bhandara lies, gradually passed to the Satavahana dynasty, who ruled the Deccan for nearly four centuries. Under the Satavahanas, Pauni retained its importance and expanded further as a trade and cultural centre.

Excavations at Pauni have yielded a wide range of coinage, including Satavahana coins, Taxila coins, Masa coins, and several portrait-type coins, which all point to long-distance trade connections. This evidence confirms that the region was well integrated into both northern and southern trade circuits during the early historic period.

The economy of Vidarbha appears to have reached its zenith during this period, with Pauni serving as a regional node in the broader urban network of the Satavahana state.

Western Kshatrapas and the Inscription of Mahakshatrapa Rupiamma

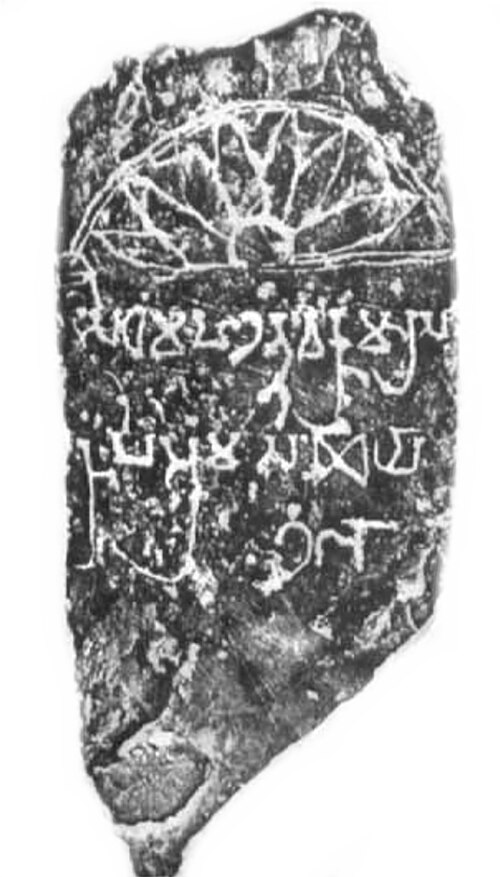

Toward the end of Satavahana rule, Pauni appears to have come briefly under the control of the Western Kshatrapas, a dynasty of Saka origin that controlled parts of Gujarat and western Maharashtra. This is supported by the discovery of a memorial pillar bearing the name of Mahakshatrapa Rupiamma, located near Pauni.

Though the duration of Kshatrapa control is unclear, the inscription suggests their presence in the region in the early 3rd century CE, indicating continued contestation over key urban centres like Pauni.

Vakataka Dynasty and the Shift of their Capital to Padmapura

In the later half of the 3rd century CE, the Vakataka dynasty succeeded the Satavahanas and ruled Vidarbha for over 250 years. During this period, Bhandara remained a politically important region, partly due to its proximity to the Narmada trade routes and partly due to strategic exigencies.

The district Gazetteer (1979) mentions that land grants issued during Vakataka rule likely led to increased settlement in areas such as Pauni. Moreover, a key episode occurred during the reign of Narendrasena, the sixth Vakataka ruler. When the Nala king Bhavadattavarman invaded Vidarbha, the capital was temporarily shifted from Nandivardhan (Nagardhan, Nagpur) to Padmapura, near modern-day Amgaon, which today lies in the nearby Gondia district. It is possible that this shift contributed to increased prosperity and prominence in Bhandara.

Following the decline of Vakataka power around the mid-6th century CE, the Kalachuris of Mahishmati, ruling from present-day Maheshwar in Madhya Pradesh, extended their authority over parts of Vidarbha, including Bhandara. Their rule appears to have lasted until the early 7th century.

By the first half of the 7th century, the Chalukyas of Badami had advanced northward into the Deccan, incorporating Vidarbha into their realm. Although their control remained largely unchallenged in western parts of the region, the eastern tracts—including Bhandara—appear to have come under the influence of a separate branch of Kalachuris based in Tripuri (modern-day Tewar, Madhya Pradesh) by the 8th century. This transfer of power is affirmed in the colonial district Gazetteer (1908).

Meanwhile, other parts of Vidarbha and the broader Deccan plateau witnessed the rise of the Rashtrakutas around 715 CE. The Rashtrakutas and the Kalachuris of Tripuri ruled contemporaneously for several generations, often controlling adjacent or overlapping territories. The Gazetteer (1908) suggests that by the 10th century, the Rashtrakutas had likely annexed eastern Vidarbha, thereby bringing Bhandara within their sphere of influence.

Toward the close of the 10th century, the region may have briefly fallen under the dominion of the Panwars (Parmars), although this remains speculative. By the 12th century, the Kalachuris of Ratnapur had reasserted control over this tract. It is during this period, in 1114 CE, that the name "Bhanara" appears in a Kalachuri inscription, marking one of the earliest epigraphic references to the region. As discussed earlier (see Etymology above), this term is considered a possible origin for the present-day name Bhandara and may reflect the district’s recognition as a distinct territorial unit or mandala under Kalachuri administration.

Yadava Rule and Hemadpanthi Mandirs in Korambi and Pinglayee

By the mid-13th century, Bhandara was incorporated into the kingdom of the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, whose rule extended across much of Maharashtra. This period saw a revival in temple architecture, especially in the Hemadpanthi style, named after the Yadava minister Hemadpant.

Remains of such mandirs have been recorded in the villages of Korambi, Pinglayee, Gaimukh, and Roha. Constructed without mortar and featuring precise stonework, the presence of these mandirs, in many ways, reflect the artistic and cultural imprint of the Yadava state on Bhandara.

Medieval Period

The early 14th century marked a political turning point in the Deccan. Following Alauddin Khilji’s conquest of Devagiri in 1294 CE, the Delhi Sultanate extended its authority into much of present-day Maharashtra. Bhandara, too, like many other regions, would have fallen within the broader territory nominally under the Sultanate's rule. Their hold on the Deccan region, however, remained tenuous. Governance was fragmented and their tenure was marked by frequent rebellions and resistance from local powers.

By the mid-14th century, this instability led to the rise of new regional kingdoms, including the Bahmani Sultanate in the western Deccan and the Gond kingdoms across the central Indian plateau. In eastern Vidarbha, which includes present-day Bhandara, the Gonds began consolidating power. They primarily ruled over the region named Gondwana, which was named after the Gond people. They gradually emerged as a loose confederation of powerful tribal kingdoms. This region included present-day eastern Vidarbha in Maharashtra, large portions of Madhya Pradesh, and western Chhattisgarh.

The major Gond polities that developed between the 14th and 17th centuries included the Garha-Mandla kingdom (centered in present-day Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh), the Deogarh kingdom (in parts of Madhya Pradesh and Nagpur, Maharashtra), and other smaller principalities such as Kherla (Madhya Pradesh), Chhindwara (Madhya Pradesh), Chandrapur (Maharashtra). Of these, the Deogarh kingdom would come to dominate eastern Vidarbha, and Bhandara district was an integral part of this territory. Over the next two centuries, their influence would come to define the political history of the district.

The Mughal Incursion into Garha and the Fate of Deogarh

In the second half of the 16th century, the Mughal Empire under Emperor Akbar sought to consolidate its hold over the Deccan and central Indian plateau. This expansion brought it into conflict with the Gond kingdoms, which had begun to emerge as significant regional powers across present-day Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Chhattisgarh.

One of the earliest confrontations between the two occurred around 1564 CE when Akbar’s general, Asaf Khan, launched an attack on the Garha kingdom. The Kingdom was then ruled by Rani Durgavati, the widow of Dalpat Shah who served as the regent for her minor son. Her valiant resistance, lasting several years, became a celebrated episode in central Indian history. However, she was ultimately defeated and killed in battle. The Mughal Empire then annexed Garha, however, Akbar restored a portion of the kingdom to Chandra Shah, her brother-in-law, in 1567 CE.

Importantly, this campaign did not extend to the eastern Gond territories around Deogarh, which included present-day Bhandara. The region remained outside direct Mughal control and was instead treated as semi-independent after the Deogarh kingdom was formed. The rulers of Deogarh were expected to pay annual tribute to the Mughals; which was a practice that both preserved their autonomy while acknowledging Mughal authority.

Jatba and the Rise of the Deogarh Kingdom

Around 1590 CE, the Deogarh kingdom was formally established by a Gond leader named Jatba. He is widely regarded as the first sovereign ruler of the Deogarh branch of the Gonds and his reign marked a decisive phase in the consolidation of Gond power in eastern Vidarbha.

Historical details about Jatba’s early life remain uncertain, but his reign is well documented. One can find his mentions in the popular Mughal-era record, Ain-i-Akbari, which reveals that Jatba, during Akbar’s reign, was recognized as a semi-independent ruler. He is said to have maintained a force of 2,000 cavalry, 50,000 infantry, and 100 elephants. It also mentions that he extended his kingdom to the west and towards the south and included in his territory the present-day districts of Betul (district in Madhya Pradesh), Chhindwada (district in Madhya Pradesh), Nagpur and portions of Seoni (district in Madhya Pradesh), Bhandara and Balaghat districts.

The Kingdom of Deogarh was likely very prosperous under Jatba’s rule. However, it is again important to note that the kingdom was semi-autonomous. Jatba acknowledged Mughal overlordship through the payment of annual tribute and he retained full control over internal administration and military affairs. Over time, however, the burden of tribute would place increasing strain on Jatba’s successors,

Conflict with the Mughals

By the early 17th century, relations between the Deogarh Kingdom and the Mughal Empire had deteriorated. Successive Gond rulers struggled to meet the financial demands imposed by Delhi. This led to repeated Mughal campaigns against Deogarh between 1637 and 1669 CE, ordered under the reign of Shah Jahan.

While these invasions did not result in direct annexation, they inflicted considerable damage. Bhandara, an agrarian district with forested interiors and fertile riverine tracts, likely suffered from resource depletion and instability.

Bakht Buland Shah and the Revival of the Deogarh Kingdom

A new phase in the history of the Deogarh Kingdom began with the rise of Bakht Buland Shah, a descendant of Jatba, who sought to restore the Kingdom’s power through strategic diplomacy. In 1986, in his early years, he travelled to the Mughal court in Delhi in 1686 to seek support in a succession dispute. There he converted to Islam to gain favour with the Mughals and was rewarded with the title of ‘Bakht Buland Shah’ by Emperor Aurangzeb. This alliance was tactical and Bakht Buland gained recognition as Raja of Deogarh and used his position to strengthen the kingdom.

By the early 18th century, Bakht Buland shifted his allegiance away from the Mughals and aligned with the Marathas. This shift was not sudden, it came at a time when the Deccan region was embroiled by intensifying conflict. Mughal authority was weakening, and the Marathas were on the rise. Bakht Buland, sensing opportunity, broke with Aurangzeb and joined hands with the Marathas to launch campaigns into Berar.

In 1702, he moved the capital of the Deogarh kingdom from the hills to the plains, founded the city of Nagpur and established it as his new seat. This shift likely increased the political importance of the Bhandara region, which lay close to the new administrative centre and along key transit routes.

During his reign, Bakht Buland introduced measures to promote settlement and economic activity within Bhandara and the wider Gondwana region. It is noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1908) that:

“Industrious settlers from all quarters were invited to Gondavana, many towns and villages were founded and agriculture, manufactures and even commerce made a considerable advance. Bhandara was not at this time a valuable appanage. There were some fertile lands in the alluvial tracts of the Wainganga and Bagh rivers and the town of Pauni was even then celebrated for the excellence of its cotton fabrics. But the centre and east of the district were covered by dense forest and tenanted only by wild animals and forest tribes. The large and valuable Zumindari of Kamtha was first granted in the middle of the eighteenth century on a payment of Rs. 60 annually.”

Bakht Buland also commissioned the construction of strategic fortifications across his territory. Among these was the Ambagarh Fort, located in present-day Tumsar taluka of Bhandara district. Built around 1700 CE, the fort occupied a commanding position along the northern routes into Bhandara and served as a key military outpost of the Deogarh kingdom.

Decline of the Deogarh Kingdom and the Rise of Raghuji Bhosale I

The death of Bakht Buland led to a period of instability. His son Chand Sultan succeeded him, but internal disputes over succession invited outside intervention. In 1738, Raghuji Bhosale I, a Maratha general based in Berar, was called upon by Chand Sultan’s widow, Rani Ratan Kuvar, to support her son’s claim.

Seizing the opportunity to expand Maratha influence eastward, Raghuji entered the region with military force. He first captured Pauni, a key commercial centre in Bhandara, before advancing towards the Bhandara fort. The fort, heavily garrisoned, withstood a 22-day siege before surrendering. On why the fort and the present-day district was important to Raghuji, the Gazetteer (1908) makes a few notes, “Bhandara was a place of strategic importance and its capture was of immense importance in the context of Raghuji's plan of eastward expansion.”

Following the annexation of the fort, Raghuji marched towards Deogarh. A fight took place between Raghuji and the then ruler of Deogarh, Wali Shah (one of the brothers of Chand Sultan, who usurped the throne upon Chand Sultan’s death). Raghuji, emerging victorious, restored the Rani’s son to power.

In gratitude, the Rani, granted him a sanad (a charter). The Sanad, as cited in the district Gazetteer (1908) states that “the fort of Pauni alongwith Balapur, Paragan Mulatai with Chikhali and 156 villages under the said paragana, the whole of pargana Marud were granted to Raghuji I and his successors in perpetuity.” Bhandara was thus formally integrated into the Maratha sphere.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Bhandara had become an important district on the eastern frontier of the Maratha Confederacy, especially for the Bhosales of Nagpur. Raghuji Bhosale I and Peshwa Baji Rao I shared the goal of expanding Maratha influence eastwards, launching campaigns into Bengal and Odisha. The district’s heavily forested terrain provided a vital route for these expeditions. The significance of the district in Maratha territorial policy is further indicated by the agreement of 1743, whereby all lands east of Berar, inclusive of Bhandara, were assigned to Raghuji’s sphere of influence.

Internal Conflict Among the Marathas

Following Raghuji’s death in 1755, succession disputes plagued the Bhosale kingdom. His son Janoji Bhosale eventually assumed control, taking the title Sena-Sahib-Subha. However, his reign was marked by tensions with the Peshwas, as competing Maratha factions jostled for control over the Deccan.

Bhandara, lying within the contested Nagpur dominion, bore the brunt of this instability. Military movements, disrupted taxation, and the uncertainty of leadership affected the local economy.

Subsequent rulers, including Mudhoji Bhosale I and later Raghuji II, restored some order, but the kingdom remained vulnerable. By the late 18th century, British influence in central India had begun to alter the balance of power.

The Treaty of Deogaon and the British

The early 19th century saw the British East India Company rapidly expand its reach through diplomacy and war. In 1803, during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, Raghuji II was forced to sign the Treaty of Deogaon after the British defeated the Maratha forces at the Battle of Argaon (modern-day Adgaon in Akola).

Under this treaty, the Bhosales ceded large tracts of territory, including Cuttack, Balasore (which both lie in Odisha), and parts of Bengal. Though Nagpur and Bhandara remained under Bhosale rule, the treaty marked a significant erosion of their autonomy. Economic decline must have likely followed, as warfare and territorial losses disrupted trade and agriculture across the region.

Pindari Raids and the Fortification of Pauni

The rising power of the British saw grave unrest in the region. As the Holkars and Scindias lost their sovereignty, there was an upsurge in violence from the Pindari (an irregular military group who had support from Holkars and Scindias) who turned to plundering towns and villages.

Pauni, which had become a flourishing textile and market town during this time is noted to have become a repeated target. The Gazetteer (1908) mentions, “Thrice the Pindaris, attracted by the fame of Pauni, swarmed to its plunder… On their second coming, the Pindaris had it all their own way. Again they came…”

To deter such attacks, Chimna Bhosale, a local commander, fortified the western face of Pauni. Portions of the bastion still stand today.

Appa Saheb’s Revolt and Resistance in Bhandara

After Raghuji II’s death in 1816, his brother Appa Saheb Bhosale (Mudhoji II Bhosale) assumed control. Though he initially entered into a subsidiary alliance with the British, tensions soon escalated. Appa Saheb, resentful of British dominance, led a brief but significant rebellion.

The revolt found support in Bhandara, especially from the zamindar of Kamtha (now part of the nearby Gondia district) and Ambagarh Fort who launched raids across the region.

The British response was swift. They defeated Appa Saheb’s forces at Pauni, with Major Wilson, in the district Gazetteer noting, “Their entire loss was estimated at about one hundred and fifty, while that of the detachment amounted to twelve killed and wounded.”

Appa Saheb fled, and British civil servant Richard Jenkins adopted Bajiba, son of Raghuji II’s daughter, as the heir. From 1818 to 1830, Jenkins governed Nagpur, which then included Bhandara, as regent for the minor king.

In 1830, Raghuji III came of age and assumed power, but his reign remained under British oversight. Upon his death in 1853 without a male heir, the British invoked the Doctrine of Lapse to annex the Nagpur kingdom and with this, Bhandara district formally came under British rule.

Colonial Period

First War of Independence, 1857

In the year 1857, a revolt, which is today widely regarded as India’s First War of Independence, swept across large parts of northern and central India as soldiers and civilians rose in defiance of British authority. Yet, in Bhandara — part of the Nagpur territories at the time — the rebellion found little traction. Contemporary interpretations attribute this absence of revolt to several factors. Some suggest that the influence of Rani Baka Bai, the second wife of Raghuji Bhosale II, played a stabilizing role; others point to the administrative vigilance of British officials, who maintained firm control over the district during a period of widespread unrest elsewhere.

Formation of the Central Provinces

In 1861, in the aftermath of the uprising and as part of a broader administrative reorganization, the British established the Central Provinces. This new entity was formed by merging the Sagar-Narmada territories with the former domains of the Nagpur Kingdom. Bhandara, being one of these Nagpur territories, was absorbed into the Central Provinces. From this point forward, the district became a part of the colonial administrative system — subject to new laws, land revenue systems, and bureaucratic structures.

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, a number of legislative and bureaucratic measures were introduced in the region. These included the enforcement of the Vernacular Press Act, increased military expenditure (especially during the Second World War), and changes to the eligibility criteria for Indian candidates entering the Indian Civil Service. While aimed at consolidating control, these policies were met with sporadic public resistance and gave rise to many local unrests and politically motivated movements.

Famines

Between 1890 and 1900, the Bhandara district experienced a period of severe agrarian distress. A succession of poor monsoons, beginning in 1892, led to recurring famines. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1908), these famines had a notable demographic impact, particularly on poorer communities. Birth rates declined sharply, while mortality rates increased significantly. In 1897, the birth rate in Bhandara as documented in the gazetteer (1908) fell to 26 births per thousand people and the death rate increased to 61 deaths per thousand people.

Local Political Dissent and Repression

In the early decades of the 20th century, as nationalist sentiment gained momentum in various parts of British India, the Central Provinces also became sites of agitation and protest. The British administration in the Central Provinces maintained a close watch on individuals suspected of involvement in political agitation. Measures taken to suppress nationalist activity included restrictions on association, press censorship, and administrative penalties. Bhandara, while not a major political centre, was nonetheless subject to these wider patterns of control.

One recorded instance from the district involved Shivraj Singh, a pensioned tehsildar residing in Rampailli. He was found to have participated in activities deemed politically inappropriate by the colonial authorities. Despite receiving a formal warning, his continued involvement led to the revocation of his pension. As a consequence, the Chief Commissioner ordered the forfeiture of his pension. The directive read:

"It is notified that whereas Shivraj Singh, a pensioned tehsildar now a resident of Rampailli in the Bhandara district, has in spite of warning participated in political agitation directed against the Government... the Chief Commissioner hereby directs that with effect from the date of this order, the pension... is forfeited."

Quit India Movement and the Tumsar Smarak

In August 1942, the Quit India Movement, a mass civil disobedience campaign led by the Indian National Congress, spread rapidly across the country. The movement found resonance in Bhandara and its adjoining areas, particularly Tumsar (now a taluka within Bhandara district) and led to a notable episode of political unrest in the district.

On 14 August 1942, a protest was organised in Tumsar town as part of the wider national campaign against British rule. A procession began near the railway station and moved toward the local police station, with participants chanting patriotic slogans such as “Bharat Mata Ki Jai.” As the group approached the station, tensions escalated. According to official reports, it is said that members of the crowd began throwing stones. In response, the police opened fire. Nine individuals were killed in the incident. On the following day, 15 August, additional demonstrations took place in Bhandara town. These, too, ended in violence, resulting in four more deaths and the arrest of eighteen people.

To commemorate those who lost their lives during the movement, a memorial which is locally known today as the Mohadi Hutatma Smarak, was erected in Tumsar at the site of the protest. This monument stands as a solemn reminder of the district's contribution to India's independence struggle.

Post- Independence

Following India’s independence in 1947, Bhandara district remained part of the Central Provinces until 1956. During that year, the implementation of the States Reorganisation Act led to the transfer of Bhandara, along with other districts of the Vidarbha region, to the newly created bilingual Bombay State. Subsequently, with the formation of the state of Maharashtra in 1960, Bhandara became part of the state’s eastern division. In 1999, Gondia district was carved out of the eastern portion of Bhandara. The district had 13 talukas before then, of these seven were transferred while Bhandara, Tumsar, Sakoli, Pauni, Lakhani, and Mohadi remained in Bhandara district.

Agriculture continued to dominate the local economy in the decades after independence. The colonial district Gazetteer (1908) recorded rice as the staple crop, and the district has long been noted for the Chinnur variety. The cultivation of this variety has persisted since many centuries, and in recent years it has received a Geographical Indication tag, affording legal protection to its association with the district.

Alongside its agricultural base, the post-independence period saw efforts to diversify the district’s economy through legislative and policy measures. These include the Industrial Disputes Acts (1947 and 1956), the Trade Unions Act (1950), and the Labour Welfare Fund Act (1953), among others. In recent years, the government has placed increased emphasis on industrial growth within the district. Initiatives include the proposed establishment of a Greenfield Power Equipment Fabrication Plant, alongside efforts to promote small and medium-scale manufacturing enterprises. Under the ‘One District One Product’ programme, local industries have received targeted support to strengthen rural entrepreneurship and develop region-specific economic potential.

Sources

Akash Prasad. 2017.Gondwana Movement in Post-Colonial India: Exploring Paradigms of Assertion, Self-Determination and Statehood. Journal of Tribal Intellectual Collective. Vol. 3.Issue 1.

Amarendra Nath. 1994.Further Excavations at Pauni.Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi.

Behram H. Mehta. 1984. Gonds of The Central Indian Highlands. Volume 1. Consent Publishing Company.

Economic Times. 2013. “BHEL to Invest Rs 5,000 Million for Greenfield Power Equipment Fabrication Plant at Bhandara.”The Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/bhel-to…

Hemant Sane. The Deogad-Nagpur Gond Dynasty.https://www.academia.edu/38055455

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1979. Bhandara District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Nupur Uppal eds. 2023. ‘History of 40,000 years ago, 32 murals, stone weapons, treasure found by the Archeology Department’. Maharashtra Times.https://marathi.indiatimes.com/maharashtra/n…

R.V Russel. 1908.Central Provinces District Gazetteer: Bhandara District, Vol A, Descriptive. Pioneer Press.

Rai Bahadur Hiralal. Inscriptions in the Central Provinces and Berar / by Rai Bahadur Hira Lal. Originally published: 2nd ed. Nagpur: Govt. Print., C.P., 1932.

Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalaya. n.d. About Durgavati.http://www.rdunijbpin.org/1317/About-Rani-Du…

Ray, H. P. 1987. Early Historical Urbanization: The Case of the Western Deccan.World Archaeology, Vol 19.

Shantanu V, Riza A, Virag S, Michael W. 2015. Recent Findings on the Early Iron Age in the Bhandara District and Wainganga Basin, Vidarbha.Bulletin of the Deccan College. Vol. 75.

Sitaram Toraskar. 2020. Pauni - An Important Early Historic Fortified Settlement and a Major Hinayana Centre on Wainganga. Indian Numismatic, Historical and Cultural Research Foundation.

TNN. 2012. Hemadpanthi temple found in Roha..https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/na…

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.