Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Lonar and its Legends

- Ram Gaya Mandir and its connection to Bhagwan Ram’s exile

- Mauryan Empire at Bhon Village

- Satavahana-Era Structures at Bhon and Paturda

- Yadavas and Hemadpanthi Mandirs

- Sant Chokhamela

- Medieval Period

- The Decline of the Yadavas and the Rise of the Delhi Sultanate

- The Bahmani Sultanate and the First Battle of Rohinkhed

- The Imad Shahis of Berar

- Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar and the Second Battle of Rohinkhed (1590)

- Buldhana Under the Mughals

- Lonar as Bishan Gaya

- Berar under Jahangir and Shah Jahan

- Sindkhed Raja & the Jadhav Family

- The Battle of Shakar Kheda, 1724

- Marathas and the Nizams

- The Battle of Sindhkhed

- Account of Sindkhed Raja by Lord Wellesley

- Under the Nizams

- Sant Gajanan Maharaj

- Colonial Period

- Khamgaon as a Prominent Commercial Centre

- Agrarian Crisis and Economic Hardship

- Gajanan Maharaj and Shegaon

- Struggle for Independence

- Post-Independence

- Sources

BULDHANA

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Buldhana district lies in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra and forms part of the Amravati division. It is known for several sites that give it a distinct place in the history and geography of Maharashtra, and in some cases, beyond. The most notable of these is the Lonar Crater, located in Lonar taluka. Formed by the impact of a meteorite on basalt rock, it is one of the few such craters in the world and continues to attract scientific interest.

Historically, the region is believed to be linked to the ancient Vidarbha kingdom mentioned in the Mahabharat. In later centuries, it came under the Maurya Empire and was subsequently ruled by a series of powers. During the eighteenth century, it became a contested area between the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad. The British later brought it under their control. The district is also known for the town of Shegaon, where Shri Gajanan Maharaj, a well-known 19th-century Sant, lived. His shrine remains an important yatra site in Maharashtra.

Etymology

The name Buldhana is believed to be derived from the words Bhil and Thana, meaning “place of the Bhils.” The Bhils are an indigenous community historically found in parts of western and central India. Local tradition, along with references in the Mahabharat, suggests that the Bhils once held control over regions such as Malwa, supporting the idea that the area may have been associated with them in earlier times. They continue to form a considerable part of the district’s population even today.

Ancient Period

Lonar and its Legends

One of the earliest glimpses into Buldhana’s history comes from the place named Lonar. The town derives its prominence from the presence of Lonar Lake, a large circular depression formed by the impact of a meteorite upon the Deccan basaltic plateau. Measuring approximately 1.2 km in diameter and over 150 meters deep, the crater is estimated to be over 50,000 years old. It remains as one of the few known impact craters in basaltic rock globally and has drawn consistent scientific interest on account of its geological profile.

Notably, the basalt surrounding the lake has been found to contain rare minerals not commonly present in terrestrial formations. A study conducted by researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai, in 2019 revealed a close mineralogical similarity between the rock samples from Lonar and those retrieved from the moon during NASA’s Apollo missions. The findings have served to further confirm the extraterrestrial character of the crater and its ecosystem. It has since been recognized as a National Geo-heritage Monument and designated a Ramsar site.

Yet, its geographical profile is not the only thing that attests to its antiquity. Interestingly, there is a very intriguing local legend that surrounds the town of Lonar. In one version of the legend, it is said that long ago, there was a rakshas (demon) named Launasur who would terrorize the sants and residents of the town. The residents of the village ardently prayed to the gods to protect them. Their prayers were answered one day by Bhagwan Vishnu, who came here, according to some versions, in the form of a child called ‘Bal Vishnu’ and in some in the form of ‘Daityasudan.’ These legends have notably been preserved in the Skanda Purana.

Other than this, the surrounding area is home to a collection of ancient mandirs, many of which are constructed in the Hemadpanthi style. Fourteen of these are traditionally said to have encircled the lake, twelve of which are dedicated to Shiva. While some of these structures lie in ruin, others remain in use, serving as enduring centers of local religious practice.

Ram Gaya Mandir and its connection to Bhagwan Ram’s exile

Another account associated with Lonar connects the area to events from the Ramayan, particularly to the period of Ram’s exile. According to local belief, he is said to have passed through this region and resided here for a time. During his stay, he is believed to have performed shraddha, ritual offerings to the dead, for his father, Dasharatha. The site identified with this event is a small Mandir known as the Ramgaya Mandir. Adjacent to it is a water tank, locally referred to as the Ramkund or Pushkar Tirtha, which is regarded as the location where the rites were carried out.

The practice continues in a ritual form to this day, which locals believe stems from this very story. The indigenous communities, who reside near the lake, often visit the kund to make pindas (rice balls) for their ancestors.

The name of the Mandir is understood to derive from this tradition. Its structure itself is notable too, as it is built in the Hemadpanthi style, which is commonly associated with the Yadava period. Though direct inscriptions are absent, it is locally believed that the mandir may have been constructed under the patronage of a Yadava ruler, possibly during the 13th or early 14th century. The Yadava dynasty, which held prominence in many parts of the Deccan between the late 12th and 14th centuries, is known to have commissioned numerous Mandirs across the region in this architectural style.

Mauryan Empire at Bhon Village

The territory that now forms the Buldhana district has, at various times, fallen under the authority of different kingdoms. Little is known of its early history; however, available archaeological findings and a few literary references allow for a general outline, particularly when viewed in relation to the broader historical developments of Vidarbha and Berar, the cultural and political regions to which Buldhana has historically belonged.

Interestingly, among the few material traces of Buldhana’s antiquity, there are indications that it was once the site of copper mining activity. In his 1934 work on the early history of the Deccan, A.S. Altekar writes that “traces of more or less extensive workings of copper mines have been discovered in the districts of Cudappah, Bellary, Chanda, Buldhana, Narsingpur, Ahmadnagar, Bijapur, and Dharwar.” Although the precise period of these mining activities is not firmly established, their presence suggests the possibility of sustained early economic activity, which could have shaped the course of much of its ancient history.

Among the earliest political powers recorded in this part of Vidarbha were the Mauryas, and the district is believed to have come under the rule of Ashoka around 256 BCE. Though references are limited, some material evidence has been found within the present boundaries of the Buldhana district that supports this attribution.

Excavations carried out at Bhon village, situated in the present Sangrampur taluka, have yielded several stone artifacts, among which two dumbbell-shaped basalt mullers are of particular interest. These objects display the distinctive surface polish commonly attributed to Mauryan-period workmanship, and their presence may be taken to indicate a modest administrative or production-related outpost operating in the region during the third century BCE.

Following the decline of the Mauryas, about 184 BCE, the district appears to have passed, though perhaps only briefly, into the hands of the Shungas, under Pushyamitra Shunga. The historical record for this period is sparse, and the degree to which Shunga authority extended into Vidarbha remains uncertain. Contemporary accounts, however, suggest a time of shifting allegiances and unsettled governance. (Refer to Yavatmal for more, where similar conditions are recorded.)

Satavahana-Era Structures at Bhon and Paturda

Between the 2nd century BCE and the 3rd century CE, the Satavahana dynasty held sway over much of the western and central Deccan. Their influence extended into parts of Vidarbha, and Buldhana appears to have been included within this broader territorial ambit.

Notably, coins and architectural remains from this period have been uncovered within the present-day district. At Bhon and Paturda, both located in the present Sangrampur taluka, the remains of stupas and other religious structures have been recorded. These are generally assigned to the Satavahana period and may be taken to indicate the presence of Buddhist institutions in the area during this time. Though the Satavahana rulers are believed to have been personally adherent to Brahmanical traditions, the dynasty is noted for its support of Buddhist establishments, which they appear to have promoted across trade routes and settled areas. The site at Bhon, in particular, is believed to have functioned as a small center of religious activity and instruction.

The Satavahanas were succeeded in the Deccan by the Vakatakas, who rose to prominence in the 3rd century CE and remained active until the 6th. The present-day Washim district, lying to the east of Buldhana, was of special importance during this period, serving as the seat of one of the Vakataka branches. While no direct remains of their administration have been found in Buldhana itself, it is plausible that, given the proximity, the district lay within their area of influence.

The period of Vakataka rule in Vidarbha is generally recognized as one of cultural activity and development. Inscriptions from the time show an increased use of Sanskrit, and references to endowments suggest the patronage of learning, religious buildings, and literary production. While no such records have been found in Buldhana yet, the district may have shared in the broader currents of artistic and intellectual life that marked the region in this period.

The Vakatakas were followed, in succession, by a number of dynasties that exercised varying degrees of authority across the Deccan. These included the Vishnukundins, Kalachuris, and the Chalukyas of Badami (6th to 8th century CE), followed by the Rashtrakutas (8th to 10th century).

It was likely during the Rashtrakuta period that the copper deposits of the Buldhana region, noted earlier, came to be of administrative significance. Although the extent of mining in this period remains unclear, it is recorded and noted by many scholars that copperplate inscriptions were frequently issued by the Rashtrakuta court, and it is possible that the copper of this region contributed to that activity.

Yadavas and Hemadpanthi Mandirs

By the close of the 12th century, the political authority in many parts of the Deccan had passed into the hands of the Yadavas of Devagiri, whose rule extended across much of present-day Maharashtra. They remained in power until the early 14th century, and their period is marked, in the material record of Buldhana district, by the appearance of a distinctive style of mandir construction known as Hemadpanthi.

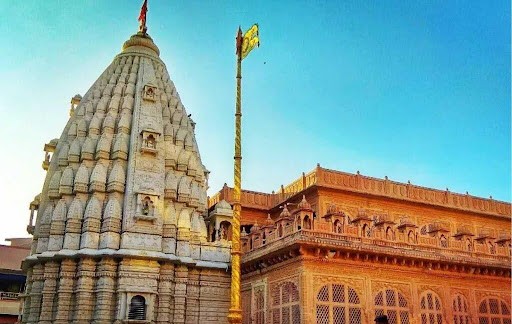

Named after Hemadpant, a minister in the Yadava court, the style is characterized by the use of black basalt, shaped and laid without mortar. Interestingly, mandirs built in this style are found throughout Buldhana. Among those noted in historical accounts are at Mehkar-Sonati, Sindkhed Raja, and Sakegaon along the Chikhli-Dhad road. Three Shiva Mandirs constructed in the Hemadpanthi style are located at Dhotra (Nandai) on the Deulgaon Raja–Chikhli road, and two further structures are found near Motala.

The most prominent of these is the Daityasudan Mandir, situated near Lonar Lake, within a cluster of fourteen mandirs that encircle the crater. The structure is executed in the Hemadpanthi manner and is of particular interest for its unfinished state. Writing in the colonial district Gazetteer (1910), Arthur Edward Nelson remarks that the work may have been interrupted “at the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century, when the Muhammadans first overran this part of the country.”

This Mandir is also connected to the legend of Launasur, the rakshas of Lonar (mentioned above). There is an image of Bhagwan Vishnu which can be found within the inner sanctum of the Mandir. There are many versions of Launasur’s legend; notably, in one it is said that Launasur lived with his sisters at this Mandir.

Sant Chokhamela

Chokhamela was a 13th–14th century saint from Maharashtra, India. He was born in Mehuna Raja, a village in Deulgaon Raja Taluka of Buldhana district, and belonged to the Mahar community, which was considered a low caste at the time. He later lived in Mangalvedha, Maharashtra. Chokhamela was introduced to the bhakti (devotional) path by the poet-saint Namdev (1270–1350 CE).

During a visit to Pandharpur, he heard Namdev’s kirtan (devotional singing), which deeply inspired him. Profoundly influenced by Namdev’s teachings, Chokhamela later made Pandharpur his home. A devoted follower of Lord Vitthal (Vithoba), Chokhamela composed numerous Abhangas (devotional poems), among which “Abir Gulal Udhlit Rang” is especially well known. He is regarded as one of the earliest poets from the lower castes in India.

Medieval Period

The Decline of the Yadavas and the Rise of the Delhi Sultanate

Towards the end of the 13th century, when the Yadavas still held significant power in the Deccan, a momentous shift occurred in the political history of Vidarbha as the Delhi Sultanate began moving southwards to the Deccan. In 1296, Alauddin Khalji, then a provincial governor under the Delhi Sultanate, led an expedition into the Deccan region. His forces reached Devagiri, the Yadava capital, and compelled its ruler, Ramachandra, to pay tribute. Although the city was not annexed at the time, the raid marked the beginning of the Sultanate's involvement in the region.

Though Devagiri remained nominally independent for a time, its subordination to Delhi was now a settled matter. In 1312, during the reign of Alauddin’s son, Qutb-ud-din Mubarak Shah, the Yadavas made an unsuccessful attempt to throw off this dependency. The rebellion was suppressed, and Devagiri was annexed in the same year. Over the following years, the political and administrative landscape of the Deccan began to change. Notably, during this period, Berar began to appear as a distinct administrative province under the Sultanate, of which Buldhana district became a constituent part.

After Alauddin Khilji's death in 1316, the Delhi Sultanate entered a politically unstable phase characterized by numerous assassinations and power struggles. In 1320, the Tughlaqs came to power in Delhi, marking a significant shift in the ruling dynasty. Unfortunately, this change of power likely brought economic hardship to Berar, including Buldhana, as many Tughlaq rulers imposed heavy and oppressive taxes to fund their wars.

The Bahmani Sultanate and the First Battle of Rohinkhed

By the mid-14th century, the authority of the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan had weakened. In 1347, a military commander named Alauddin Bahman Shah declared independence and established the Bahmani Sultanate, marking a new phase in the political history of the region. The newly formed kingdom, with its court at Gulbarga, brought under its control large parts of the Deccan, including the province of Berar, as mentioned above, within which the present-day Buldhana district is situated.

Under the Bahmani rulers, Berar was administered as one of the kingdom’s major provinces. While specific references to Buldhana remain limited, its location along major overland routes made it a passage zone for armies and supply lines. It appears that the district, during this period, served primarily as a military and transit zone, its towns and villages likely drawn into the logistical demands of conflict.

One such conflict occurred in 1437, when Nasir Khan Faruqi, the ruler of Khandesh, entered Berar in response to a personal grievance, as his daughter, married to a Bahmani prince, was said to have been mistreated. The Bahmani governor of Daulatabad, Khalaf Hasan Basri, was dispatched to intercept the invasion. The two forces met at Rohinkhed, a town located in the present-day Buldhana district. Nasir Khan’s army was defeated and driven back to Burhanpur, the capital of Khandesh, which was then sacked.

The Imad Shahis of Berar

By the closing decades of the 15th century, the Bahmani Sultanate had begun to fragment into smaller successor states. One of these was the Imad Shahi dynasty of Berar, founded by Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk, a former Bahmani governor who declared independence around 1490. The new kingdom was based at Ellichpur (present-day Achalpur, in Amravati district), and Berar became a distinct regional polity under his rule.

The Imad Shahi period was marked by frequent conflicts with neighboring powers, including the Ahmadnagar, Bijapur, and Golconda Sultanates. In 1563, Burhan Imad Shah allied with several of these kingdoms against Ahmadnagar. However, soon after, he was overthrown by Tufal Khan, a powerful noble within his court. This internal power shift left Berar vulnerable.

In 1565, Murtaza Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar invaded Berar, citing Tufal Khan’s refusal to join his military alliance. The invasion was marked by considerable violence. Contemporary records suggest large-scale slaughter, and in 1572, Ahmadnagar forces completed their conquest of Berar, bringing the territory, including Buldhana, under the rule of the Nizam Shahi dynasty.

Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar and the Second Battle of Rohinkhed (1590)

By the late 16th century, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate had entered a period of internal instability. A succession dispute arose with Burhan Nizam Shah, son of Husain Nizam Shah and brother of Murtaza, at its center. Years before, he had taken refuge at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar and returned to the Deccan in 1590, supported by Raja Ali Khan of Khandesh, a vassal of the Mughal court. He aimed to challenge the legitimacy of his nephew, Ismail Nizam Shah, who had been elevated to the throne by a powerful faction led by a noble named Jamal Khan.

The opposing forces met at Rohinkhed (Buldhana district), and the engagement resulted in Burhan’s victory with Jamalkhan slain and the young Ismail taken captive. This battle marked a significant turning point in the power dynamics of the region and placed Buldhana momentarily at the center of the contest for the Ahmadnagar throne.

Interestingly, the town of Rohinkhed had already held some political and religious standing in the years preceding this battle. In 1582, a mosque was commissioned there by Khudavand Khan Mahdavi, a follower of Jamal Khan. Though now in ruins, the structure once bore an inscription noting its construction in A.H. 990 (1582 CE). The mosque was, at the time, held in high regard, said by some to be second only to Mecca in sanctity, perhaps pointing to the aspirations and prominence of the Jamal Khan faction before its fall. It also stands as a testament to the religious and political prominence Rohinkhed once held.

The victory at Rohinkhed allowed Burhan to assert his claim over Ahmadnagar. But dynastic conflict within the Sultanate continued to weaken its stability. In 1596, taking advantage of the disorder, Prince Murad, son of Akbar, launched a strategic campaign against Ahmadnagar. Facing pressure, Chand Bibi, acting as regent, was compelled to cede Berar to the Mughals in exchange for a temporary reprieve.

Buldhana Under the Mughals

With the cession of Berar to the Mughals in 1596, the territory comprising the present-day Buldhana district was formally integrated into its administrative structure. Berar was designated one of the Subahs (provinces) of the Deccan under Emperor Akbar, and the broader region was divided into Sarkars, or revenue districts.

Within this framework, Buldhana was split among three such Sarkars: Mehkar, Narnal, and Baithalwadi. Notably, several talukas of the present district—including Mehkar, Deulgaon Raja, Chikhli, Malkapur, Nandura, and Jalgaon Jamod—are listed under these divisions in the Ain-i-Akbari, the administrative compendium compiled by Abu’l Fazl, Akbar’s court historian. The following figures from the Ain-i-Akbari provide a glimpse into revenue assignments under the Mughal regime:

|

Current Talukas of Buldhana |

Akbar Sarkar |

Revenue under Akbar’s sarkar (in dams) |

|

Chikhli |

Baithalwadi |

20,00,000 |

|

Mehkar |

Mehkar |

25,60,000 |

|

Deulgaon Raja |

Mehkar |

56,00,000 |

|

Malkapur |

Narnala |

1,12,00,000 |

|

Nandura |

Narnala |

12,00,000 |

|

Jalgaon Jamod |

Narnala |

1,00,00,000 |

Land revenue formed the principal source of state income in the province. The revenue reforms associated with Raja Todar Mal, Akbar’s finance minister, were introduced in Berar and aimed at standardizing assessment and collection. Known as the bandobast system, this scheme sought to establish a rational basis for revenue demands by surveying and classifying land according to productivity.

While assessments were high, Mehkar alone was assessed at over 25 lakh dams, and Malkapur even more; it is doubtful whether these sums were ever fully realized. The region’s political volatility, alongside its geographic remoteness from Delhi, presented ongoing difficulties in collection. Yet, Buldhana’s contribution to Berar’s fiscal structure was significant.

Lonar as Bishan Gaya

Another brief but telling reference to Buldhana appears in the Ain-i-Akbari, where the town of Lonar, located in the sarkar of Malkapur, is described as "Bishan Gaya" by Brahmans of the time. The name, meaning the Gaya of Vishnu, draws a parallel with the sacred site of Gaya in Bihar and reflects Lonar’s longstanding religious significance in Hindu tradition.

The recognition of Lonar in the Mughal record, albeit brief, attests to its spiritual importance well beyond the confines of the district.

Berar under Jahangir and Shah Jahan

Following the death of Emperor Akbar in 1605, his son Jahangir ascended the throne of the Mughal Empire. During his reign, Berar, including the territory now comprising Buldhana district, faced continued unrest. The neighboring Ahmadnagar Sultanate remained a persistent adversary, and the contest over Berar led to shifting control between regional and imperial authorities.

A significant turning point came in 1626, when Berar was ceded to the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar for a sum of twelve lakh rupees. This transfer of territory led to the withdrawal of Mughal authority in parts of the province, including sections of Buldhana. The region soon fell into administrative disarray.

The following year, in 1627, Jahangir died, and his death precipitated further uncertainty. The Mughal succession crisis, coupled with declining central control, contributed to instability throughout the Deccan. Shah Jahan, Jahangir’s son, ascended the throne in 1628 and quickly moved to reassert control over the region. His efforts culminated in a prolonged conflict with the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, which lasted until 1633. Armies from both sides are known to have passed through Balaghat, a term historically applied to the upland areas of the Deccan, including parts of southern Buldhana.

The Mughal campaign ultimately succeeded in restoring Berar to Mughal authority. However, the district likely suffered from the logistical demands of war. Further compounding the hardship, the famine of 1630, which affected much of the Deccan, is reported to have had a devastating effect on Berar’s otherwise fertile lands.

In the wake of military consolidation, the Mughal administration introduced a series of territorial reorganizations. In 1634, Shah Jahan divided the Deccan into two broad administrative divisions: Balaghat (southern) and Payanghat (northern). Of the present-day talukas in Buldhana, Malkapur, Jalgaon Jamod, and Khamgaon were assigned to Payanghat, while Chikhli and Mehkar were placed under Balaghat. This system, however, was short-lived. By 1636, the province was once again unified, and Berar, including all parts of the present Buldhana district, was consolidated under Mughal authority.

The relative peace that followed allowed for more stable administration, but the balance of power in the Deccan was already beginning to shift. The death of Shah Jahan and the rise of Aurangzeb coincided with the emergence of a new political force: the Marathas, under Chhatrapati Shivaji, whose influence would grow significantly in the decades to follow.

Sindkhed Raja & the Jadhav Family

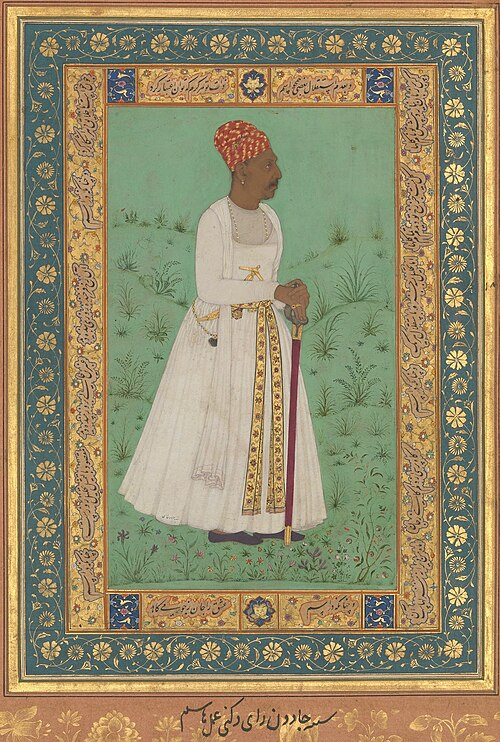

Interestingly, there is a town in Buldhana district that holds particular historical significance, named Sindkhed Raja. It is known today largely because of its connection to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, but it was also a place of considerable prominence in its own right. This settlement became the seat of a powerful local family, the Jadhavs, whose influence extended across both the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and the early Mughal presence in the Deccan.

The rise of the family is most often associated with Lakhauji Jadhav Rao, whose name appears frequently in both tradition and historical record. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1910), he is said to have “lived by tilling land under the village of Sindkhed” until his “extraordinary talent and bravery” brought him the watan of the Deshmukhi of Sindkhed, sometime around the mid-16th century.

By the final decades of the 1500s, Lakhauji had emerged as an important cavalry commander. He is recorded as having held a jagir to support 10,000 horses under the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and later 15,000 under the Mughals. His service appears to have been pragmatic, adapting to the shifting balance of power between regional and Mughal interests in the Deccan. Notably, he also played a supporting role in the career of Maloji Bhosale, grandfather of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj.

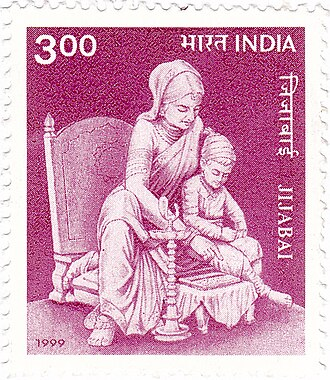

Notably, it was here, in Sindkhed, that Jijabai, the daughter of Lakhauji and mother of Shivaji, was also born and raised. The town thus occupies a central place in the early social and political history of the Maratha Empire.

Several remnants of the Jadhav family’s presence remain. Among them is the Bhuikot Palace, where Jijabai is said to have spent her childhood. Another structure is the Shri Balaji Mandir, a historic religious site that is situated in Deulgaon. The Mandir is often referred to as the ‘Tirupati of Maharashtra’ and was originally built by Raja Jagdevrao Jadhav, the great-grandson of Lakhuji Jadhav, in the 17th century.

There is also an old fort in the town, which lies “half-finished” and “uncompleted.” Notably, the fort belonged to and was established by the Jadhav family. A.E. Nelson (1910), in the district colonial Gazetteer, mentions a very interesting anecdote on why this fort was left “uncompleted.” The condition of the fort, in many ways, is correlated to the fall of the family from prominence. He mentions that, in 1650, an envoy from the Mughal Empire named “Murshid Ali Khan, being displeased with the reception given him by the Jadhavs, restored the jagir to the Kazi…the construction of which was stopped by this envoy.”

The Battle of Shakar Kheda, 1724

In the century that followed, the district became entangled in the political rivalries that would leave a considerable impact on the region. In the early 18th century, the decline of Mughal authority was becoming increasingly visible in the Deccan. Local governors and military commanders, once loyal to the Mughal court, began asserting greater independence. One such figure was Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, who had served as the Mughal Viceroy of the Deccan since 1714. His growing power, however, unsettled the court at Delhi.

In 1724, Mubariz Khan, a rival officer, was dispatched by Emperor Muhammad Shah to challenge Asaf Jah’s authority. The two forces met near the town of Shakar Kheda in what is today the Buldhana district. The engagement ended decisively: Mubariz Khan was defeated and killed, and Asaf Jah emerged as the new power in the region.

With this victory, Asaf Jah declared his independence and founded the Asaf Jahi dynasty, marking the beginning of the Hyderabad State. Berar, including Buldhana, now came under the nominal authority of this new regime, though its administration would remain contested.

Marathas and the Nizams

Over the following decades, the balance of power in the Deccan continued to shift. The Marathas, long expanding their influence under Chhatrapati Shivaji’s successors, began asserting their claim over Berar through the collection of chauth and sardeshmukhi taxes, extracted from territories under notional Mughal control.

At the same time, the Nizams of Hyderabad maintained their own claim over the region. In 1728, following the Battle of Palkhed, a treaty was concluded between the Nizam and the Marathas. Under its terms, while Berar remained formally under the Nizam’s dominion, all administrative and diplomatic affairs in the six subahs, including Berar, would now be conducted through the agency of the Marathas.

This compromise, however, did not ease tensions. Instead, it laid the groundwork for prolonged rivalries, in which Buldhana would find itself frequently drawn in.

The Battle of Sindhkhed

By the middle of the century, tensions between the Marathas and the Nizam boiled over once again. In 1758, the district became the scene of another significant confrontation: the Battle of Sindkhed, which was fought near the present-day town of Sindkhed Raja.

The impact of the battle on the region was likely considerable. As the site of direct conflict, Buldhana would have borne the strain of troop movement, resource extraction, and local disruption. The economy and demography of the area may have been deeply affected as military activity drained supplies and unsettled daily life.

At the same time, events in the broader subcontinent were taking a new turn. The English East India Company, which had until recently remained a coastal trading power, was beginning to insert itself into the politics of the interior. Its interest in Berar, and in the fragile balance of power in the Deccan, would grow in the years to come.

Account of Sindkhed Raja by Lord Wellesley

The closing decades of the 18th century were marked by a rising contest between the English and the Marathas. These conflicts culminated in the Treaties of Deogaon and Anjangaon, signed in 1803, which aimed to resolve a protracted struggle. As part of the agreement, the Marathas retained control of Berar to the east of the Wardha River, which included Buldhana.

It is from this period that a stark description of the Sindkhed Rajas’s condition can be found. Writing as Governor-General of Fort William, Lord Wellesley remarked, “Sindkhed is a nest of thieves. The situation of this country is shocking; the people are starving in hundreds, and there is no government to afford the slightest relief.”

Under the Nizams

A year later, in 1804, the political map of Berar shifted again. In 1804, the Partition Treaty of Hyderabad was once again signed between the Nizams of Hyderabad and the Marathas, which redrew the boundaries of Berar. Under its terms, territories including Sindkhed and other parts of Buldhana were transferred to the Nizams.

But the treaty did not bring peace. Political instability persisted well into the early 19th century. In 1822, yet another treaty was signed between the Nizams and the Marathas, and the provinces lying west of the Wardha River, consisting of the Buldhana district, were ceded to the Nizams.

Governance under the Nizams appears to have been highly decentralized, with real power often resting in the hands of local elites and monopolists. Rebellions, factional disputes, and lawlessness were recurrent, and the burden of mismanagement was frequently borne by the rural population. Over time, Berar’s agricultural productivity declined, and many parts of the province, including Buldhana, experienced periods of marked instability. These conditions, coupled with the growing interests of the East India Company in the Deccan, set the stage for yet another shift.

Sant Gajanan Maharaj

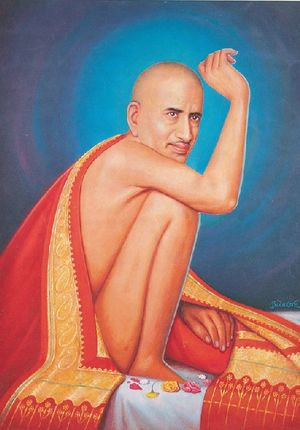

Sant Gajanan Maharaj made a profound contribution to the spiritual heritage of Maharashtra, revitalising faith through his enigmatic presence as a perfect Avadhuta (a saint beyond all worldly conventions).

His origins are a celebrated mystery, as he was first seen as a young man on February 23, 1878, in Shegaon. This town, then a part of Akola district (and now in Buldhana district), became his karmabhoomi and a major pilgrimage centre. He was discovered picking leftover food grains, a sign of his complete detachment from ego and social norms.

Unlike saints with known lineages, Gajanan Maharaj had no known birth name, family, or external Guru; he was widely regarded as a self-realised Paramahansa and an incarnation of Lord Ganesha. He spent his entire life in and around Shegaon, guiding devotees through his simple, often cryptic, actions rather than long discourses. He performed countless miracles to bolster the faith of the common people, teaching the unity of God and the importance of selfless service, summed up in his famous mantra "Gan Gan Ganat Bote." His legacy continues through the massive charitable, educational, and spiritual work of the Shegaon Sansthan.

Colonial Period

The formal advent of British administration in Berar occurred in 1853 through a treaty between the East India Company and the Nizam of Hyderabad. Though the territory remained nominally under the suzerainty of the Nizam, effective control now passed into the hands of the Company. This reorganization divided Berar into North and South divisions, with Buldhana notably becoming the administrative headquarters of the former.

In 1864, a further political rearrangement took place. The talukas of Malkapur, Mehkar, and Chikhli were separated from West Berar and formed into a new district known as the Mehkar district. A few years later, in 1867, Buldhana was designated as the district’s headquarters, a position it retains to this day.

In 1903, the British Government of India entered into a new agreement with the Nizam, whereby Berar was permanently leased to the British for administrative purposes. As a result, Berar was brought into closer alignment with the British Indian administrative framework. Further territorial adjustments occurred in August 1905, when the talukas of Khamgaon and Jalgaon were transferred from Akola district to Buldhana district. With these changes, Buldhana now became part of the Central Provinces and Berar.

Khamgaon as a Prominent Commercial Centre

Among the talukas brought under the jurisdiction of Buldhana, Khamgaon occupied a position of particular note. Situated along established inland trade routes, the town had, by the latter half of the nineteenth century, developed into a principal market for raw cotton. Contemporary accounts describe it as one of the most active trading centers in the region. Interestingly, it is mentioned in the District Gazetteer (1971) that in 1870, Khamgaon was regarded as “the largest cotton mart in India.”

The commercial prominence of the city, however, stretches even further back. What many might not know is that, during the medieval period, Khamgaon was located along an ancient trade route and was famous for its thriving silver trade.The built remains of this earlier prosperity are few, but some structures survive as a marker of the town’s fortified past.

Agrarian Crisis and Economic Hardship

Notably, the emergence of Khamgaon as a center of the cotton trade corresponded with changes in the agrarian landscape of the district. From the mid-nineteenth century, the cultivation of cotton expanded steadily across rural Buldhana, supported by administrative policies that encouraged the extension of tillage and the reorganization of cropping patterns.

Berar’s black soil and dry climate were considered well-suited to cotton, and the region gained renewed importance following disruptions to overseas supply during the American Civil War. Notably, Laxman Satya (1998), in his paper, mentions how the province was noted by contemporary British observers as offering “the most suitable climate and soil for cotton” and was popularly referred to as “the navel of India.”

To support this expansion, many changes took place. Uncultivated land was gradually brought under cultivation, and new roads were laid to connect producing areas with depots and railheads. We know from Satya's paper that the Deputy Commissioner of Buldhana wrote that, “The cultivation had extended during the settlement term so much that there was practically no cultivable land left unoccupied. In 1869, when the original revenue settlement was introduced into almost the whole taluk, the area of culturable and assessed land lying unoccupied was about 67,100 acres. In 1896-97, the unoccupied area was only 11 acres.”

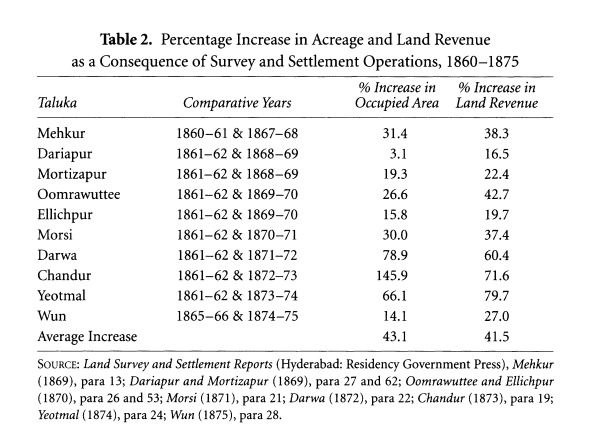

Increase in occupied area and land revenue in selected Berar talukas, 1860–1875, consequent on survey and settlement. The figures illustrate the rapid extension of cultivation and the enhanced revenue assessment imposed during the period.

The emphasis on commercial cropping, however, also brought many dire consequences to the local farming community. The emphasis on cotton also seems to have reduced the share of food crops in many areas, diminishing food security at the household level. At the same time, access to basic agricultural inputs deteriorated. Livestock became harder to maintain due to the loss of pasture and the rising costs of fodder and firewood. One official inquiry in 1881 remarked that the cultivator could “no longer fell a tree… or get grass to thatch his hut without cost.” At the same time, patterns of payment suggest a growing reliance on moneylenders. Revenue was often paid in lump sums, not directly by the cultivators themselves but through advances made on their behalf, an arrangement which, as Satya (1998) notes, led to rising levels of indebtedness across the region.

Gajanan Maharaj and Shegaon

Amid the broader changes taking place in the late nineteenth century, Shegaon, a small town which lies within the district, began to emerge as a significant religious site. This was largely due to the arrival of Gajanan Maharaj in 1878, a spiritual figure who would come to be widely revered across the Vidarbha region.

Gajanan Maharaj came to Shegaon at the age of 30 in 1878 and lived here until he attained Sanjeevan Samadhi (voluntary withdrawal from the physical body) in 1910. Despite being a very popular figure, much about the Sant’s life, notably, remains unknown. It is mentioned in the district Gazetteer (1976) that “as per the information given by the residents, no one has heard him speaking about himself.” The mystery surrounding him, it is noted, made many locals regard him as a miraculous figure.

However, there are a few interesting stories that surround his early life. It is recorded in the district Gazetteer (1976), that some believe that the sant “must have been the descendant of the Peshwa Nanasaheb who led the War of Independence of 1857.” According to this story, Gajanan Maharaj may have been “living in obscurity after his defeat at the hands of the British.” There is another story, which says that the Maharaj was a patriot who fought alongside the Peshwas in the Vidarbha region.

Many of the speculations of his involvement in the tumultuous political scenario at the time are due to his association with pivotal figures such as Lokmanya Tilak and Dadasahab Kharpade, who played an important role in India’s independence movement. It is noted that Gajanan Maharaj met Lokmanya Tilak in 1907 in Akola and, after hearing of his imprisonment, “blessed the great patriot of India and prophesied that the cause for which Tilak was fighting would meet with success.”

By the early 20th century, efforts were underway to formally commemorate the Maharaj’s presence in Shegaon. In 1908, the Shri Gajanan Maharaj Samadhi Mandir was constructed around the site of his samadhi (final resting place).

The Mandir, which stands today, is perhaps the first that was dedicated to the Sant. It was, notably, commemorated in the presence of Gajanan Maharaj in 1908 at the same time as when the parent body of the Mandir, Shri Sant Gajanan Maharaj Sansthan was first formed. Over time, the Mandir has become one of the most prominent religious sites in Vidarbha and is often referred to as the ‘Pandharpur of Vidarbha,' a reference to which indicates both its spiritual importance and the scale of yatris it continues to attract.

Struggle for Independence

By the early 20th century, the political environment in Buldhana was increasingly influenced by national developments. Events such as the partition of Bengal (1905), the formation of the Indian National Congress, and the administrative unification of Berar with the Central Provinces contributed to a broader political awakening in the district.

A number of individuals from Buldhana participated in the independence movement, though many of their contributions remain underrepresented in wider accounts. Among the more widely remembered figures is Narayan Jaware, who is locally known as the “Mahatma Gandhi of Buldhana.” In an early act of protest, he removed the British flag from a government building in Khamgaon and hoisted the Indian tricolor in its place. He was thirteen years old at the time.

Namdev Punjaji Pawar was another participant in the anti-colonial movement. He played an active role in spreading nationalist ideas in the district and remained involved in various forms of local resistance. In Chikhli, Ramakrishna Khatri was associated with revolutionary activity and is believed to have contributed to the iconic song Rang De Basanti Chola, written by Ram Prasad Bismil. Khatri was also involved in the Kakori train robbery case, which was a significant event in the revolutionary phase of the movement.

Educational institutions were also part of the district’s contribution to the nationalist cause. The Tilak Rashtriya Vidyalaya, established in Khamgaon in 1921 by Dr. Parsanis and his associates, was founded to promote Swaraj, Swadeshi, and National Education and encourage the boycott of foreign goods. The school became a center for spreading nationalist ideas at the local level and continues to function to this day.

Other figures such as Vitthal Laxman Ingle were also involved in the movement, though their names are less widely recognized. Further documentation of such contributions is available through the Digital District Repository of Buldhana, which preserves archival records and accounts of the district’s role in the freedom struggle.

Post-Independence

From 1947 to 1956, Buldhana and other districts in the Vidarbha region remained part of the Central Provinces and Berar. After independence, this territory became part of the newly formed state of Madhya Pradesh, with Nagpur as its capital. Following the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, Buldhana, along with other Marathi-speaking areas of Vidarbha, was transferred to Bombay State. When Maharashtra was created in 1960, the district became part of the new state.

Today, Buldhana district is administratively divided into 13 talukas, namely, Buldhana, Chikhli, Deulgaon Raja, Malkapur, Motala, Nandura, Mehkar, Sindkhed Raja, Lonar, Khamgaon, Shegaon, Jalgaon Jamod, and Sangrampur. These talukas are grouped under six revenue subdivisions for ease of administration, which are Buldhana, Mehkar, Khamgaon, Malkapur, Jalgaon Jamod, and Sindkhed Raja. Each taluka functions as a key unit of local governance and revenue administration within the district.

Sources

A.E. Nelson, I.C.S. 1910. Central Provinces District Gazetteer: Buldhana District. Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta.

A.P. Crósta et al. 2019. Impact cratering: The South American record – Part 1. Geochemistry. Vol.79. Issue 1. Science Direct.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

B.C. Deotare. 2006. Late Holocene Climatic Change: Archaeological Evidence from the Purna Basin, Maharashtra. Geological Society of India. Vol 68. Issue 3.https://www.geosocindia.org/index.php/jgsi/a…

Bhartiya Touring Party. 2023. Mystery of Lonar Lake. Youtubehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yKXFezkaBAQ

Bhaskar C. Deotare. 2007. Discovery of Structural Stupa at Bhon, District Buldana, Maharashtra. Vol. 37, Puratattva.https://www.academia.edu/75220678/Discovery_…

Buldhana District: Official Website, Digital District Repository Detail, Wikipedia.https://buldhana.nic.in/en/

Gajanan Maharaj. Shri Gajanan Maharaj Sansthan, Shegaon. Gajanan Maharaj. https://www.gajananmaharaj.org/sgmsenglish/a…

IGNOU. n.d."Unit 27: Early State Formation in the Deccan."eGyanKosh. Indira Gandhi National Open University.https://egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/…

Jadunath Sarkar. 1949. Ain-i-Akbari of Abul-Fazl-Allami. Volume 2. Ed.2. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta.

Laxman D Satya. 1998. Colonial Encroachment and Popular Resistance: Land Survey and Settlement Operations in Berar (Central India),1861-1877. Vol. 72, no. 1, Agricultural History.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3744291.pdf

Laxman D. Satya. 2016. The Political Economy of Famines In the 19th Century: A Case Study of Berar Deccan in a Comprehensive Perspective. Vol. 77. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/e26552610

Lokmat. 2015. टिळकांच्या प्रेरणेने स्थापन झाले टिळक राष्ट्रीय विद्यालय. Lokmat.https://www.lokmat.com/buldhana/tilak-nation…

Maharashtra State. 1976. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Buldhana. Directorate of Government Print. Stationery and Publications. Maharashtra State.

Manappa Bheemappa. 2014. Economic conditions of Karnataka during Rashtrakuta Rule. Vol. 4, no 4. Indian Journal of Applied Research.https://www.worldwidejournals.com/indian-jou…

P.D. Sabale et al. 2010. Geomorphological Studies Around Early Historic Site Of Bhon, Dist. Buldhana. Vol 70, no. 71. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute.https://www.jstor.org/stable/42931238?seq=5

Raka Das. 2023. Expansion of Buddhism in Early Deccan.Vol. 9. no 6, International Journal for Innovative Research in Multidisciplinary Field.https://www.ijirmf.com/wp-content/uploads/IJ…

Sahapedia. In Conversation with Hans Bakker. Sahapedia.https://www.sahapedia.org/conversation-hans-…

Santosh Unecha. 2014. Gomukh Temple, Lonar Crater Lake, Maharashtra. Pune to Pune.https://punetopune.com/gomukh-temple-lonar-c…

Shiv Kumar Tiwari. 2002. Tribal Roots of Hinduism. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi.

Snehal Fernandes. 2019. Mineral Contents of Buldhana’s Lonar Lake Similar to Moon Rocks: IIT Bombay Study. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/m…

Stewart Gordon. 2003. The Marathas - Cambridge History of India.Vol. 2. Part 4. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Times of India. 2024. The Mysterious Lonar Crater Lake: The Indian Lake That Surprises Even NASA.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/etimes/t…

UNESCO. Lonar Lake - A Natural Wonder.https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5575/.https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/557…

Vidya Nesarikar. 2023. Mystery of the Crater Lake. The Hindu.https://www.thehindu.com/children/mystery-of…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.