Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Lokapur and the Lunar Lineage

- Early Stone Age Occupation at Bhatala and Mowad

- Paleolithic and Microlithic Habitation at Papamiyan Tekdi

- Megalithic Monuments at Hirapur

- The Spread of Buddhism & Vijasan Tekdi Caves

- Vakataka Rule and Urban Growth at Bhadravati

- Mentions in the Writings of Hiuen Tsang

- Mana & Naga Kings

- Medieval Period

- Formation and Rise of the Gond Kingdom

- Foundation of Chandrapur City and the Anchaleshwar Mandir

- Later Gond Rulers and Shifts in Regional Power

- Establishment of Maratha Rule

- The End of Maratha Rule and British Annexation

- Colonial Period

- First War of Independence in 1857

- Early Administrative Changes

- Early Nationalism and the Chandrapur District Association

- The Chimur Kranti of 1942

- Aftermath and Inquiries

- Patru Bhusari and the Martyrs of Chimur

- Baba Amte and Anandwan Ashram

- Post-Independence

- Administrative Reorganisation

- Sources

CHANDRAPUR

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Chandrapur district, lying in the eastern tract of the present-day state of Maharashtra, possesses considerable antiquity. Traces of early human occupation have been discovered at various sites, indicating the presence of prehistoric communities. Though literary records from antiquity are scant, the region is believed by some scholars to correspond with the territory of the Haihaya rulers of Kosala, as referenced indirectly in the account of the Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang, who visited India in the 7th century C.E. Following the decline of early powers, the area appears to have passed through a period of political fragmentation, marked by the brief ascendancy of local chieftains.

Greater stability was introduced with the rise of the Gond rulers, who established their seat at Chanda (modern-day Chandrapur). The Kingdom of Chanda emerged as a principal Gond polity in the region, with its authority extending over a considerable portion of the surrounding forested and plateau terrain. Subsequently, the district came under the rule of the Maratha rulers from the Bhosale dynasty before falling under British control with the annexation by the East India Company. During the 20th century, several parts of the district became associated with nationalist activities; the village of Chimur, in particular, gained prominence during the disturbances of 1942. These areas became centres of local resistance and contributed to the broader national struggle.

Etymology

The origins of the district’s name are particularly interesting and linked to what is believed to be its ancient history. The district was previously called Chanda, denoting the moon and its association with the moon is deeply rooted in local folklore. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1909), it is recounted that “in the Treta Yuga Lokapur was governed by a king of the race of moon, who altered its designation to Indupur (city of the moon).”

Perhaps based on this, interestingly, the district was renamed as Chandrapur in 1964. It is a combination of two words with “Chandra” denoting the moon and the suffix “pur” signifying a town or an urban area.

Ancient Period

The early history of the region now forming the Chandrapur district is not extensively documented in classical sources. However, archaeological evidence and local traditions together offer important insights into its ancient cultural landscape, revealing continuous human presence from the Paleolithic era through the rise of urban centres under historical dynasties.

Lokapur and the Lunar Lineage

One of the earliest cultural references to the region now known as Chandrapur comes from oral traditions that speak of an ancient city called Lokapur, which is believed to be the seat of Devi Mahakali. These accounts suggest that the site predates formal human settlement and was ruled by a king belonging to the soma-vaṁśa (lunar lineage).

Interestingly, as mentioned earlier, this lineage is believed to be tied to the district’s etymology. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1909), it is said that “in the Treta Yuga Lokapur was governed by a king of the race of moon, who altered its designation to Indupur (city of the moon).”

Early Stone Age Occupation at Bhatala and Mowad

One of the earliest traces of human presence in Chandrapur district was recorded in 2023, when Lower Paleolithic stone tools were discovered at Bhatala and Mowad. Documented by researcher Tushar Begade, the finds included hand-axes, cleavers, picks, and scrapers made from locally available materials such as red sandstone, quartzite, and chert.

Preliminary analysis suggests that these tools belong to the Acheulian tradition, placing them within a timeframe of approximately 15 lakh to 2 lakh years ago. If further confirmed, they would represent some of the oldest known evidence of human activity in this part of eastern Vidarbha.

However, the integrity of the sites has been significantly compromised. Begade reported that over 75 percent of the locations documented in early 2023 had already been damaged or destroyed within a few months of discovery, underscoring the need for urgent conservation measures.

Paleolithic and Microlithic Habitation at Papamiyan Tekdi

Another major prehistoric site and perhaps one of the first to be discovered in the district lies at Papamiyan Tekdi, near the Jharpat River, about 12–15 km east of Chandrapur town. Excavated in the 1960s by the Archaeological Survey of India, the site has yielded tools representing all three phases of the Paleolithic period.

The earliest tools belong to the Acheulian and Oldowan traditions (ca. 1,50,000–1,00,000 BCE), and include bifacial hand-axes, cleavers, and scrapers. Middle Paleolithic tools show improved shaping techniques, while microlithic tools from the later phase (ca. 30,000–10,000 BCE) were made from materials such as chert, chalcedony, agate, and jasper.

The site, situated between two perennial rivers, appears to have served as a strategic habitation zone throughout the Stone Age. Seasonal streambeds in the area still expose artifacts today, and archaeologists believe that further excavations may uncover fossil remains linked to early human occupation.

Megalithic Monuments at Hirapur

Another important archaeological site lies at Hirapur village in Chimur taluka, where four large megalithic dolmens have been documented. Dolmens are burial structures made from large stone slabs, typically used as tomb markers or memorials. At Hirapur, they were constructed using locally available laterite and are among the largest of their kind in Maharashtra. Based on typology and associated material, the site is dated to around the 2nd or 3rd century BCE, during the late Satavahana or Asmaka period.

The site is notable for several reasons. Fragments of iron slag found in the vicinity suggest early knowledge of iron-smelting, a relatively uncommon feature at megalithic burial sites in the region. Unlike most dolmens, which are typically associated only with funerary use, those at Hirapur appear to have served both ritual and burial functions. The location continues to be used as a cremation ground by local tribal communities, indicating a long-standing continuity of practice. Although interest in the site has grown since 2012, it is said that formal protection and documentation remain limited.

The Spread of Buddhism & Vijasan Tekdi Caves

Over time, Chandrapur district gradually became part of larger political formations and was drawn into broader patterns of administration, trade, and religious exchange that connected it to neighbouring parts of Vidarbha and the Deccan. The spread of Buddhism appears to have been one of the most prominent developments during this period. One of the earliest archaeological markers of this influence is found at Vijāsan Tekdī, located in Bhadravati taluka.

The site consists of a group of rock-cut caves carved into a laterite hill, and is considered one of the earliest and largest Buddhist cave complexes in the Vidarbha region. Based on structural features and stylistic elements, the caves are dated to the 1st century CE, during the reign of Satakarni of the Satavahana dynasty, who is known for patronising Buddhist institutions across the Deccan.

In the 19th century, the caves were repurposed as cattle shelters and were briefly recorded by Alexander Cunningham during his surveys. In recent decades, the site has regained religious importance and has hosted International Buddha Dhamma conventions attended by monks and representatives from across India and abroad. The largest cave at Vijasan Tekdi has been designated a Monument of National Importance by the Archaeological Survey of India.

Vakataka Rule and Urban Growth at Bhadravati

Between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE, the region now comprising Chandrapur district appears to have come under the influence of the Vakataka dynasty, which ruled much of Vidarbha and central India. Although no direct inscriptions from the dynasty have been yet found within the district, Bhadravati (historically referred to as Bhandak) is often speculated to have developed as an urban settlement during this period.

Among the early proponents of this connection was Alexander Cunningham, who suggested that the name "Bhandak" may be a later corruption of "Vakataka." However, the site has long been known for Shaiva worship, and other scholars such as R. V. Russell argued that the town’s name derives instead from Bhadra, an epithet of Shiva. According to this interpretation, the settlement may have taken shape around the Bhadranag Mandir, a local temple dedicated to Shiva.

Russell further speculated that Bhadravati may once have extended from Bhatala in the north to Chandrapur city in the south, a distance of nearly 45 km with the presence of ruins of Mandir and deep, rock-cut stepwells supporting its identification as a prominent early settlement.

Mentions in the Writings of Hiuen Tsang

Buddhism appears to have played a significant role in Chandrapur’s early history. The earliest known literary reference to the region is tied to this tradition. In 639 CE, the Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang) visited the kingdom of Kosala and described its capital as a major centre of Buddhist learning. He wrote that the “King is of the Kshatriya caste deeply reverences the law of Buddha and is well affected towards learning and the arts. There are one hundred Sangharams (Buddhist monasteries) here and ten thousand priests (monks).”

Interestingly, three sites have been suggested as the possible location of this capital. General Cunningham proposed Chandrapur, while others identified Vairagadh in the neighbouring Gadchiroli district. The colonial district Gazetteer (1909), however, favours Bhandak (present-day Bhadravati), citing the presence of Buddhist cave temples and local traditions of its former extent (see Visajan Tekdi Caves above).

If true, this would make Bhadravati one of the earliest documented centres of Buddhist activity in the region and a prominent seat of this Kingdom.

Mana & Naga Kings

By the 9th century CE, the region comprising present-day Chandrapur and adjoining parts of Gadchiroli came under the rule of the Mana kings. According to oral traditions recorded by Major Lucie Smith in the Settlement Report of 1869, the Manas held authority over Wairagarh and surrounding areas, including forts at Rajoli and Manikgarh.

According to some scholars, the Mana rulers may have been associated with the Nagvanshi lineage of Bastar, possibly functioning as a branch of the broader Kshatriya clan. While this connection remains speculative, the presence of Naga iconography and shared religious motifs has been cited to support this theory.

The influence of the Mana kings is reflected in several structures across the region. One oral tradition attributes to them the restoration of the Bhadrabagh shrine at Bhadravati, considered the only Shaiva shrine in the district from that period. Another significant site associated with their legacy is Manikgad Fort, also known as Gadchandur, situated in present-day Chandrapur district.

The fort was originally called Manikagad, named after Manikadevi, the tutelary deity of the Mana Nagas. It is widely believed that the fort was initially constructed in the 9th century CE, likely under Mana or Naga patronage.

Built using large blocks of black stone, Manikgad was a formidable defensive structure in its time. The rampart walls enclose a central valley, within which lie the remains of old buildings and storehouses. Traces of residential apartments can still be seen against the fort walls.

Medieval Period

The medieval history of Chandrapur is closely intertwined with the emergence and expansion of the Gond polity of Chanda, one of the four principal Gond kingdoms that came to define the central Indian landscape between the 13th and 18th centuries. The Gonds, an indigenous community with deep roots in the forested plateaus of central India, developed a socio-political order that resisted external conquest for centuries and left a lasting imprint on the region’s cultural and administrative structures.

Formation and Rise of the Gond Kingdom

The earliest traditions regarding Gond rule in the region are preserved in Major Lucie Smith’s 1869 Settlement Report and in the Chandrapur District Gazetteer (1909), which record oral narratives and genealogical accounts now lost. According to legend, the fragmented Gond tribes were first united under a wise and powerful leader named Kol Bhil. He is said to have taught his people iron smelting and to have led them in revolt against the ruling Mana or Nagvanshi kings of Wairagarh, eventually toppling their two-century-long dominion.

With the decline of the Manas, the Gonds consolidated their power and established their first stronghold at Sirpur (Telangana) on the right bank of the Wardha River, while retaining control over the ancient fortress of Manikgad (mentioned above), previously held by the Mana kings. The Sirupr-Chanda Gond dynasty (later the Chanda polity) ruled uninterrupted for nearly five centuries, and oral tradition lists a total of nineteen kings. According to the colonial district Gazetteer, they are:

- Bhim Ballal Singh (870–895 CE): The first known king in the dynasty. Tradition credits him with founding Gond power in the region.

- Khurja Ballal Singh (895–935 CE)

- Hir Singh (935–970 CE)

- Andia Ballal Singh (970–995 CE)

- Talwar Singh (995–1027 CE)

- Keshar Singh (1027–1072 CE)

- Dinkar Singh (1072–1142 CE): Remembered in local lore as a learned ruler; encouraged cultural exchanges.

- Ram Singh (1142–1207 CE)

- Surja Ballal Singh or Sher Shah Ballal Shah (1207–1242 CE)

- Khandkia Ballal Shah (1242–1282 CE): Founded the city of Chandrapur and moved the capital from Sirpur.

- Hir Shah (1282–1342 CE)

- Bhuma and Lokba (jointly, 1342–1402 CE)

- Kondia Shah (1402–1442 CE)

- Babaji Ballal Shah (1442–1522 CE)

- Dhundia Ram Shah (1522–1597 CE)

- Krishna Shah (1597–1647 CE)

- Bir Shah (1647–1672 CE)

- Ram Shah (1672–1735 CE): Adopted in infancy; reigned for 63 years. His rule represents the last phase of independent Gond strength before external threats grew.

- Nilkanth Shah (1735–1751 CE): The final sovereign Gond king. He was defeated and imprisoned by Raghoji I Bhosale, marking the end of Gond rule and the beginning of Maratha control over Chanda.

Foundation of Chandrapur City and the Anchaleshwar Mandir

It wasn’t until the reign of King Khandkia Ballal Shah, the 10th ruler in the Gond lineage, that the political centre of the kingdom was moved from Sirpur to Chandrapur and founded Chandrapur City. There is a very interesting story that is tied to its foundation. According to legend, King Ballal Shah suffered from a chronic skin disease, described as a condition marked by tumours. On the advice of his queen, he left Sirpur and settled on the opposite bank of the Wardha River, where he constructed the fort of Ballalpur (which lies in Chandrapur district).

Some time after, during a hunting expedition near the dry bed of the Jharpat river, he discovered a waterhole and bathed in it. That night, he is said to have slept soundly for the first time in years, and the next day many of his ailments had vanished.

Upon investigating, the royal couple uncovered five cow footprints in rock, each miraculously filled with water. The site was believed to be sanctified by Achaleshwar, a manifestation of Bhagwan Shiv, who is said to have remained fixed to that spot since the Treta Yuga. In a dream, the deity instructed the king to build a mandir over the sacred waters. Obeying this divine command, Ballal Shah commissioned the construction of the Anchaleshwar Mandir, which still stands today as a major religious and cultural landmark in Bazar Ward, Chandrapur.

The same legend also tells of an unusual omen that followed shortly after. A white-spotted hare was seen chasing the king’s hunting dog in an erratic, zigzag path around the sacred site. The queen interpreted this reversal of roles as a highly auspicious sign and advised the king to found a new city following the path of the hare’s chase.

He accepted the advice, and Chandrapur was established along that very trajectory. The city was fortified accordingly, with bastions placed at strategic points mirroring the movement of the hare. Supervision of the construction was entrusted to Tel Thakurs, Rajput officers in service to the Gond king.

Later Gond Rulers and Shifts in Regional Power

Following the death of Babaji Ballal Shah around 1597, the Gond kingdom of Chanda saw a gradual weakening of royal authority. His successor, Dhundia Ram Shah, is remembered unfavourably in the Gazetteer (1909), which describes him as “foolish, drunken, untruthful, and treacherous.” Despite these criticisms, his reign marked an important architectural milestone which is the completion of the fortified walls around Chandrapur city. These fortifications were inaugurated with elaborate ceremonies, during which thousands of Brahmans were fed, and large tracts of land were granted to loyal subjects.

He was succeeded by Krishna Shah (r. 1597–1647), who is credited with restoring administrative order. His policies focused on civil consolidation rather than military expansion. Krishna Shah is noted for reducing the army and granting land to many of its leaders, particularly in the eastern and southern tracts of the kingdom. During his reign, the longstanding political relationship with Deogarh underwent a significant shift. The Gond rulers of Deogarh, who had previously been subordinate to the Chanda kings, were formally recognised as independent. While the Gazetteer notes this was likely a formal acknowledgment of an existing reality—Deogarh under Jatba had grown considerably stronger—it marked a key moment in the regional decentralisation of Gond authority.

Despite these internal changes, the Gond kingdom of Chanda remained relatively independent and was never fully incorporated into the Mughal Empire. Their rule, however, came to an end in 1751 when Raghoji I Bhosale of Nagpur seized Chanda, marking the beginning of Maratha dominance.

Establishment of Maratha Rule

According to the Gazetteer (1909), earlier Maratha interest in the region is recorded as early as 1718, when the Raja of Satara attempted to annex Chandrapur. He dispatched Kanhoji Bhosale to invade Gondwana, but the campaign is said to have failed.

It was Raghoji I Bhosale who finally succeeded in 1751. After capturing Chanda, he imposed a treaty of partition, requiring the surrender of two-thirds of the kingdom’s revenue to the Marathas. He then imprisoned Nilkanth Shah—the last Gond ruler—and his son Ballal Shah in Ballarpur Fort, formally ending the Gond dynasty.

Following his death in 1755, a power struggle broke out among his four sons: Janoji, Sabaji, Mudhoji, and Bimbaji. Janoji, the eldest, initially succeeded him as ruler of Nagpur, but his brother Mudhoji, with support from the Peshwa’s court in Pune, challenged his authority.

This conflict escalated over several years. In 1769, Peshwa Madhavrao led a military expedition into Chanda, intensifying the rivalry. Eventually, a political compromise was reached: the Peshwa confirmed Janoji as the ruler of Nagpur, while Mudhoji was granted control over Chanda.

After Mudhoji’s death in 1788, his son Raghoji II assumed power in Nagpur. Meanwhile, Venkoji, Raghoji II’s younger brother, was given the title Sena Dhurandhar and placed in charge of Chanda and Chhattisgarh. Venkoji, also known as Nana Sahib, is remembered for a brief period of prosperity during which he rebuilt forts, constructed a palace, and commissioned temples in the city of Chandrapur.

However, the region soon entered a period of hardship. In 1789, the Erai River flooded, causing widespread damage to the town and its surrounding areas. A more serious shift occurred during the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803), when British forces allied with Raghoji II Bhosale captured Cuttack, as well as key areas west of the Wardha River, including Manikgarh and Sirpur. This marked the beginning of British territorial expansion in the region.

At the same time, Pindari raiders—loosely organized armed groups—emerged and plundered villages across the district.

The End of Maratha Rule and British Annexation

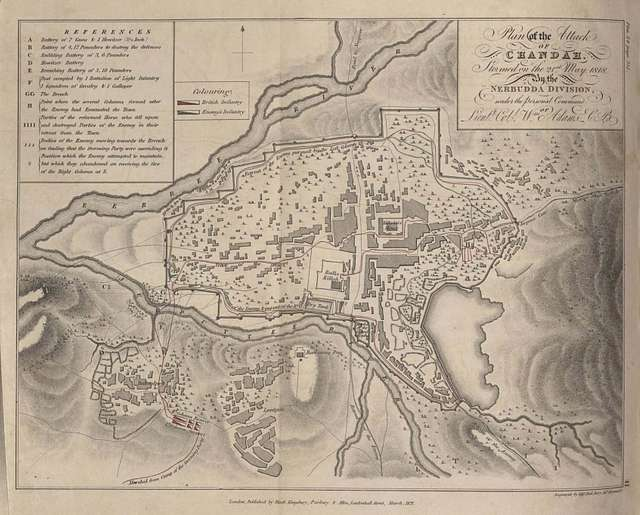

Following the death of Raghoji II in 1816, a new power struggle unfolded. His son, Parsaji, was quickly overthrown and killed by Mudhoji II, also known as Appa Sahib. Just two years later, in 1818, the Third Anglo-Maratha War broke out. In Chandrapur, the British troops attacked and captured Chanda Fort — a strategic victory that symbolised the final collapse of Maratha military control in the region. Appa Sahib was defeated by the British and forced to sign a subsidiary alliance, making Nagpur (and by extension, Chandrapur) a princely state under British suzerainty.

Although the Bhosale dynasty remained in place as nominal rulers, actual governance was handed over to a British commissioner, who reported directly to the Governor-General of India. Chandrapur, once ruled by independent Gonds and then by the Bhosales, was now part of the British imperial system.

In 1830, Raghoji III, a young member of the Bhosale family, was installed as ruler under British oversight. However, when he died without a male heir in 1853, the British annexed the kingdom outright under the Doctrine of Lapse, a policy used to absorb Indian princely states into the empire. This officially ended Maratha rule and made Chandrapur a part of British India.

Colonial Period

Following annexation, Chandrapur became part of British India, and a British commissioner was appointed to govern the district. The first to assume this role was Mr. R. S. Ellis of the Madras Civil Service, who took office on 15 December 1854. That same year, Chandrapur was designated as an independent district, and it was eventually integrated into the Central Provinces (a large administrative region under British control). Chandrapur remained within this structure until India’s independence in 1947.

First War of Independence in 1857

The uprising of 1857–58, often referred to as the First War of Independence, marked the first widespread challenge to British authority in India. Although its principal centres lay in the northern and central parts of the country, its effects extended to other regions, including Chandrapur. At the time, British administrative control in Chandrapur district had only recently been established, beginning in 1854. Within three years, signs of discontent and resistance began to surface, particularly in the zamindari and forested areas of what are now Chandrapur and Gadchiroli districts. These areas, governed by local landholding families and inhabited by indigenous communities, became sites of organised opposition to British presence and policy.

The most prominent instance of this resistance was led by Baburao Sedmake, zamindar of Molampalli (Etapalli taluka in Gadchiroli district), who mobilised armed support in the interior areas of the district.

In early 1858, he assembled a force of approximately 500 men, drawn from the Gond, Maria, and Rohilla communities, and initiated engagements against British detachments. On 13 March 1858, his forces encountered and repelled British troops near Nandgaon (present-day Chandrapur district). Subsequently, he was joined by other zamindars, including Vyankat Rao of Adpalli and Ghot (both now in Gadchiroli district), increasing the strength of the force to over 1,200 men.

Engagements continued into April, with recorded confrontations at Saganapur on 19 April and Bamanpet on 27 April (both in present-day Chamorshi taluka, Chandrapur district). A telegraph camp at Chinchgundi, located on the Pranhita River (near the present-day Telangana–Maharashtra border), was also attacked during this period.

Unable to defeat Sedmake through direct confrontation, Deputy Commissioner Crichton turned to local intermediaries. He issued a warning to Rani Lakshmibai of Aheri (present-day Aheri, Gadchiroli district), a zamindarini in the area, that punitive measures would follow if she did not assist in Sedmake’s capture. She complied, and Sedmake was taken into custody in July 1858. He briefly escaped but was recaptured on 18 September 1858.

He was brought to Chandrapur, tried under Act XIV of 1857, and executed on 21 October 1858 in front of the Chandrapur Jail. A memorial at the site of his execution continues to commemorate his role in India’s early resistance to British rule.

Early Administrative Changes

In the year 1874, the district saw a number of administrative changes as three tehsils, Mul, Warora, and Brahmpuri, were officially established, marking an early step in defining the internal boundaries of the district. Around the same time, the Upper Godavari district of the Madras Presidency was dissolved, and four of its tehsils were merged into Chandrapur. These were reorganised into a single unit with its headquarters at Sironcha (now part of Gadchiroli district).

A crucial shift occurred in 1895 when the administrative headquarters was relocated to Chandrapur, highlighting the growing prominence of this strategic location. Subsequently, in 1905, a new tehsil was created at Gadchiroli, comprising zamindari estates transferred from the existing tehsils of Brahmapuri and Chandrapur. In 1907, a portion of territory was detached from Chandrapur district and reassigned to neighbouring districts as part of wider boundary adjustments.

Early Nationalism and the Chandrapur District Association

By the early 20th century, Chandrapur and Gadchiroli began to see the early stirrings of Indian nationalism. In 1913, the Chandrapur District Association was founded as a non-violent political platform that brought together emerging middle-class leaders from both urban and rural communities, including zamindars, merchants, and peasants. The Association served as a voice for the region, advocating for political rights and fair governance.

Some of its key activities included:

- Petitions for tax relief during famines or surplus years

- Demands for fair crop assessments, especially when revenue officials were accused of overcharging

- Formal complaints by merchants seeking redress from colonial authorities

While operating within legal and constitutional limits, the Association helped build political awareness in the district and served as a precursor to later nationalist movements, especially those influenced by Lokmanya Tilak and the early Indian National Congress.

The Chimur Kranti of 1942

Years later, one of the most significant anti-colonial uprisings in Chandrapur’s history occurred during the Quit India Movement in 1942. This was a nationwide civil disobedience campaign led by Mahatma Gandhi, who issued the famous “Do or Die” call to action. In Chandrapur district, the movement took a dramatic turn in the village of Chimur, where it became known as the Chimur Kranti.

According to historian Amit Bhagat, the revolt began on the night of August 15, 1942, during a Khanjari Bhajan (devotional gathering) led by Sant Tukdoji Maharaj, a spiritual leader from Vidarbha. Just days after Gandhi’s arrest, the people of Chimur rose in protest. Riots erupted, leading to attacks on the police and the burning of ten forest depots. Several British officials were killed, and communication to Chimur was cut off by destroying a road bridge.

To suppress the revolt, the British dispatched 200 European soldiers and 50 Indian constables from Wardha. The crackdown was brutal. Women in the village suffered heavily, with reports of rape, pillaging, and violent repression.

One elderly woman, Dadibai Begde, is said to have courageously approached the District Magistrate and pleaded for mercy, which helped bring an end to the violence. However, atrocities had already occurred.

Aftermath and Inquiries

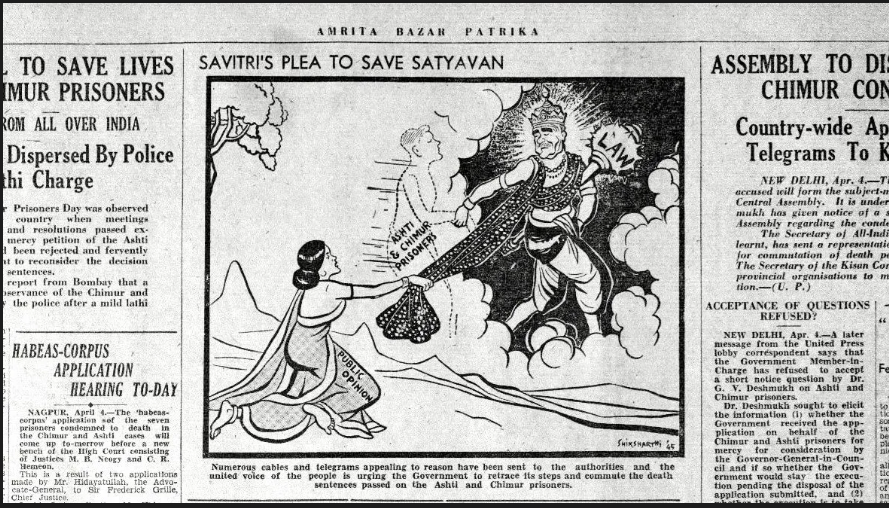

In late August 1942, the Bar Association of Chanda demanded an official inquiry into the violence. Though the government initially ignored these appeals, women’s rights activists from Nagpur such as Vimlabai Deshpande, Dwarkabai Deoskar, Vimal Abhyankar, Ramabai Tambe, and Durgabai Wazalwar—visited Chimur and investigated the sexual violence.

Their findings were publicised by leaders like Usha Mehta, who broadcast the news on October 28, 1942, through Azad Hind Radio, run by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose from Berlin. The reports caused national outrage.

Under public pressure, a commission of inquiry was finally appointed. The inquiry revealed that 13 women had been raped by European soldiers, and four minor girls had been assaulted. Women were also robbed of their jewelry and possessions. About 400 individuals in Chimur were charged with violence, leading to trials where 29 people were sentenced to death, and 43 received life imprisonment. These events remain a dark chapter in the district’s colonial history.

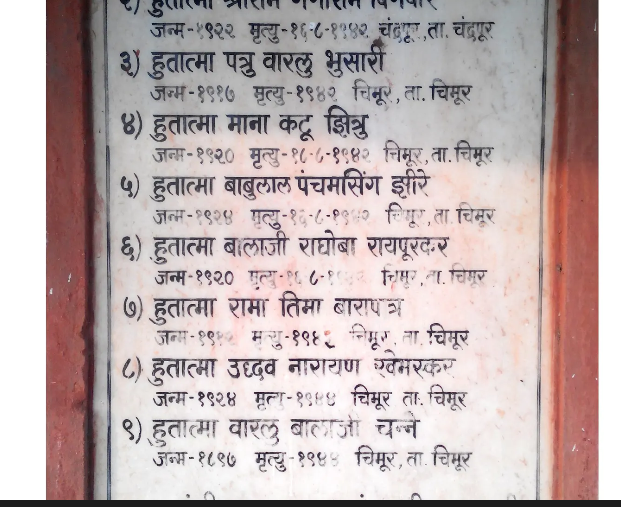

Patru Bhusari and the Martyrs of Chimur

Among the many who rose during the Chimur Kranti was Patru Bhusari, born in 1917 in Chimur. A labourer by trade, he became a key figure in the movement. He was one of the 29 individuals sentenced to death after the revolt, though his sentence was later reduced to life imprisonment after widespread appeals by civil rights groups.

Patru endured severe torture in jail and was released to avoid fatalities among political prisoners. Though his exact date of death is unknown, his story remains a symbol of the resistance and suffering of Chandrapur’s people during the freedom struggle.

Today, his memory is honoured through a memorial and a library in Chimur named Hutatma Patru Varalu Bhusari. The names of other Chimur martyrs are also preserved in the village as a reminder of the sacrifices made.

Baba Amte and Anandwan Ashram

Baba Amte, revered as a modern Gandhian saint, made a monumental contribution to humanity by dedicating his life to the service and empowerment of people afflicted with leprosy. He was born as Murlidhar Devidas Amte on December 26, 1914, in Hinganghat, Wardha, to a wealthy land-owning family.

Trained as a lawyer, he abandoned his successful practice to join India's freedom struggle. His life's mission, however, was sealed by an encounter with a leprosy patient, which inspired him to fight the social stigma, which he called "Mental Leprosy." It was here, on barren, rocky land, that he founded the Anandwan ("Forest of Joy") ashram in 1949. This was not a charity home but a revolutionary centre for social reform, where patients were treated and rehabilitated, building a self-sufficient community with their own hands. His philosophy, "Work Builds, Charity Destroys," restored dignity and purpose to thousands who had been outcast, creating a thriving model of creative humanism and selfless service.

He passed away in 2008 in Anandwan in Chandrapur District.

Post-Independence

Administrative Reorganisation

Prior to Indian independence, Chandrapur formed part of the Central Provinces and Berar under British administration. In 1950, this area was reorganized as the state of Madhya Pradesh, with Nagpur designated as its capital. Following the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, the Marathi-speaking areas of Madhya Pradesh (including Chandrapur) were transferred to Bombay State.

This arrangement remained in place until 1960, when Bombay State was bifurcated to create the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. Chandrapur became part of Maharashtra and was placed under the administrative jurisdiction of the Nagpur Division, where it continues to remain.

The present boundaries of the district were shaped by further changes in the post-Independence period. Rajura taluka, previously part of Adilabad district in Hyderabad State, was transferred to Nanded district following the reorganization of Hyderabad in 1948, and later reassigned to Chandrapur district in 1959. A subsequent reorganization followed the 1981 Census, during which the talukas of Gadchiroli and Sironcha were carved out to form the separate Gadchiroli district in 1982.

At present, Chandrapur district comprises the following talukas: Chandrapur, Ballarpur, Bhadravati, Warora, Chimur, Nagbhid, Brahmapuri, Sindewahi, Mul, Gondpipri (also spelled Gondpimpri), Pombhurna, Saoli, Rajura, Korpana, and Jivati (sometimes spelled Jiwati). These boundaries reflect administrative adjustments carried out over several decades.

Sources

Amit Bhagat. 2019. Baburao Sedmake: Adivasi Hero of 1857. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Amit Bhagat. 2019. Saving Maharashtra’s Stone Age Legacy. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Amit Bhagat. 2020. Chimur Kranti: A village rises to ‘the Quit India’ call. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

B.G Kunte. 1973. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Chandrapur District. Government Printing, Stationary and Publications, Mumbai.

bat400. 2012.Megalithic burial site, also a place of worship, unearthed. The Megalithic Portal.https://www.megalithic.co.uk/comments.php?si…

Indian Culture Portal. Chanda Fort.https://indianculture.gov.in/digital-distric…

Russel V. ed. 1905. Central Provinces District Gazetteers: Chanda District. Pioneer Press, Allahabad.

Sarfaraz Ahmed. 2025. Prehistoric Sites Bhatala, Mowad Dating 2 Million Years on the Brink of Destruction. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

Shashishekhar Deogaonkar. 2007. The Gonds of Vidarbha. Concept Publishing Company.

William Wilson Hunter. 1908. Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1908-1931. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.