Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Antiquity of Surpanath Hill

- Grishneshwar Jyotirlinga and Early Shaiva Traditions

- Pratishthana and the Early Legends of Paithan

- Pratishthana as the Capital of Satavahanas

- Paithani Weaving and Indo-Roman Trade in Ancient Paithan

- Ajanta and the Spread of Buddhism in the Region

- Ellora and the Patronage of the Rashtrakutas

- Devagiri as the Capital of the Seuna Yadavas

- Sant Nivruttinath, Sant Dnyaneshwar, and Muktabai

- Medieval Period

- The Yadava Capital of Devagiri and Its Fall

- The Jhatyapali Narrative and the Question of Royal Alliances

- Malik Kafur’s Reconquest and Yadava Rebellion (1313–1317)

- The Tale of Deval Devi and Prince Khizr Khan

- Daulatabad as a Short-Lived Capital under the Tughlaqs

- The Daulatabad Mint

- Himroo Fabric

- Mentions in the Travels of Ibn Battuta

- Fragmentation of the Sultanate and the Rise of Malik Ambar

- Sant Eknath

- Mughal Consolidation and the Deccan Headquarters

- The Maratha Presence and Shivaji’s Raids

- Aurangabad as the Southern Capital of Emperor Aurangzeb

- The Architectural and Sacred Legacy of Aurangzeb

- Nizams of Hyderabad and the Decline of Aurangabad

- Battle of Palkhed, 1728

- Treaty of Mungi Shevgaon, 1728

- Relocation of the Nizam’s Capital from Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar

- British Alliance and the End of Maratha Influence

- Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountacy

- Local Resistance and the Bhil Uprisings

- The First War of Independence, 1857

- Anant Laxman Kanhere and Revolutionary Networks

- Birth of Cotton Industry, 1889

- Development of Railway Communications

- Post-Independence

- Sources

CHH. SAMBHAJI NAGAR

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

The district of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar (formerly known as Aurangabad) occupies a place of considerable antiquity and historical importance in the Deccan region. Situated strategically on trade and pilgrimage routes, the area has, from early times, served as a center of commercial activity, religious movements, and intellectual endeavor. It is particularly noted for its contributions to the arts (particularly architecture, sculpture, and painting), many of which are preserved in the celebrated cave complexes of Ajanta and Ellora, now designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The urban centers of Paithan, Daulatabad, and the district headquarters itself have also long functioned as major centers of cultural development and are closely associated with a distinguished lineage of sants, poets, scholars, and craftsmen whose influence extended beyond the region.

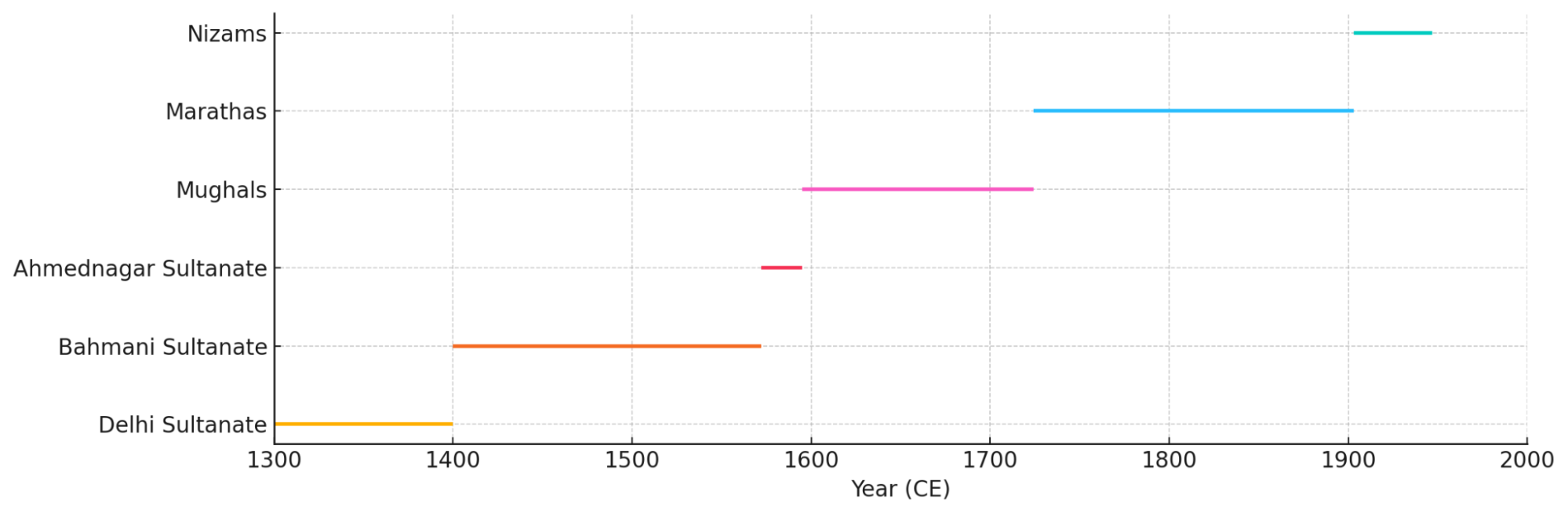

Administratively and politically, the district has passed through successive phases of control, beginning with the early Deccan polities and continuing under the dominion of the Delhi Sultanate, the Bahmani and Ahmadnagar Sultanates, the Mughal Empire, and the Marathas. The name of Malik Ambar, the influential minister of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, is particularly linked with the district’s development, notably in terms of its urban planning and military fortification. Under the Mughals, the region attained particular prominence during the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb, who resided here for an extended period during the later years of his rule. In the colonial period, the British governed the district indirectly as part of the princely Hyderabad State. During this time, the district was marked by periodic local resistance, the earliest documented instance dating to 1822. The historical layers of these varied regimes remain visible in the architecture, settlement patterns, and fortifications that define the landscape to this day.

Etymology

The erstwhile name of the district, Aurangabad, has historical significance and is derived from its association with the 6th Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb. The first part of the name, Aurang, is derived from the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, who was the ruler of the Mughal Empire from 1658 to 1707. The suffix -abad is of Persian origin and means ‘city’ or ‘place,’ which was commonly used in the names of cities and regions that were influenced by Persian culture and administration.

The district has officially been renamed as Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, and its current designation is derived from the second Chhatrapati (16 January 1681–11 March 1689) of the Maratha Empire. He was the eldest son of Chhatrapati Shivaji, the founder of the Maratha Empire.

Ancient Period

Antiquity of Surpanath Hill

Among the earliest references to the area now forming Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district are those preserved in the traditions associated with the Ramayan and Mahabharat. According to local accounts, the Paṇdavas are believed to have traversed this region during their exile and contributed to fortifying the hill of Devagiri, later known as Daulatabad.

To the northwest, near the village of Kanhar, lies Surpanath Hill. It is locally regarded as the residence of Surupnakha, sister of Ravan, who is said to have dwelt here in solitude following her encounter with Ram. The hill remains a place of regional memory, connected with ancient wanderings and events that continue to form part of the district’s oral traditions.

Grishneshwar Jyotirlinga and Early Shaiva Traditions

Not far from the basalt ridges of Daulatabad lies the village of Verul, an ancient settlement where the well-known Grishneshwar Mandir lies. It is one of only twelve mandirs in India that are considered sacred Jyotirlinga mandirs, where devotees believe Bhagwan Shiv revealed himself. Because of this, it is one of the most important Shaiva mandirs in the country and has been a major yatra center for many centuries.

There is a well-known story behind the Mandir’s origin. According to a traditional account from the Shiva Purana, a sage named Sudharma lived in this area with his wife, Sudeha. The couple had no children. Sudeha, hoping to have a child in the family, asked her husband to marry her younger sister, Ghushma, who was deeply devoted to Lord Shiva. Ghushma followed a regular practice of worship; each day, she made 101 small Shiva lingas and placed them in water as part of her prayers. In time, she gave birth to a son.

As the years passed, Sudeha became jealous and, in secret, killed the child. But Ghushma, even in her grief, did not lose her faith. She continued her prayers as usual. Then, one day, her son returned alive, unharmed. It is believed that Shiv himself appeared and offered to punish Sudeha. But Ghushma forgave her sister and asked Shiv to do the same. Pleased by her devotion and kindness, Shiva declared that he would remain at that spot forever, in the form of a Jyotirlinga. That place became known as Ghushmeshwar, which over time came to be called Grishneshwar.

The Mandir, which lies today, has gone through many changes. It was destroyed more than once, first during invasions by the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century, and again during conflicts between the Mughals and the Marathas. In the 16th century, Maloji Bhosale, grandfather of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, took up the task of restoring it. A later rebuilding was done in the 18th century by Queen Ahilyabai Holkar of Indore, who supported many temple restorations across India. Though the current temple is not ancient in its structure, it stands on a site that has been sacred for over a thousand years. Its location, near the famous Ellora caves and along what was once an old southern trade route (Dakshinapath), shows how this part of the district has long been connected to spiritual life and pilgrimage.

Pratishthana and the Early Legends of Paithan

The town now known as Paithan, located on the banks of the Godavari River, is another such place in the present-day district that has long been held in regarded as one of the oldest settlements in the Deccan region. In early Sanskrit texts, it appears under the name Pratishthana and is remembered both as a center of political rule and as a place linked to the beginnings of an ancient royal lineage.

A well-known account of its origin is found in traditional sources. It tells of a King named Sudyumna, said to be the son of Manu, who is regarded as the first man in Hindu tradition. One day, while hunting, Sudyumna entered a forest that was sacred to Bhagwan Shiv. It is said that anyone entering this forest would be transformed into a woman. Sudyumna was no exception, as he was changed into a woman and took the name Ila.

While living as Ila, she met Buddha, the son of Chandra (the moon god), and the two were married. They had a son named Pururavas. Later, Sudyumna prayed to be restored to his original form, and after performing the Ashvamedha Yajna, a royal ritual involving the symbolic sacrifice of a horse, he regained his male form. The Rishi Vasishtha then advised him to establish a new city. That city became Pratishthana, and Sudyumna’s descendants were said to belong to the Somavamsa, or Lunar Dynasty, through their connection to Chandra.

Whether taken as legend or cultural memory, this story reflects the longstanding significance of Paithan in early traditions. It was regarded as a place where royal dynasties began and where rulers established their seats of power. For many centuries afterwards, Paithan remained an important center of rule, religion, and trade. It is one of the most frequently mentioned towns in the early history of the Deccan, and its name has carried importance through many different periods.

Pratishthana as the Capital of Satavahanas

By the 3rd century BCE, Paithan came under the expanding rule of the Mauryan Empire. Though no major Mauryan inscriptions have been found directly within the district, the area likely formed part of the empire during the reign of Emperor Ashoka. With the decline of the Mauryas, power shifted to the Satavahanas, one of the earliest dynasties native to the Deccan. The Satavahana kings are said to have chosen Paithan, which was then still known as Pratishthana, as their capital.

The first ruler of the dynasty, Simuka, is credited with establishing his seat here. From Paithan, the Satavahanas extended their rule over a vast portion of western and central India. They played a vital role in promoting trade, particularly along inland routes and river networks, and were important patrons of Buddhist institutions. Though many of their cultural contributions survive in places beyond the town itself, Paithan’s role as a political and administrative center during their rule remains one of the key markers of its ancient importance.

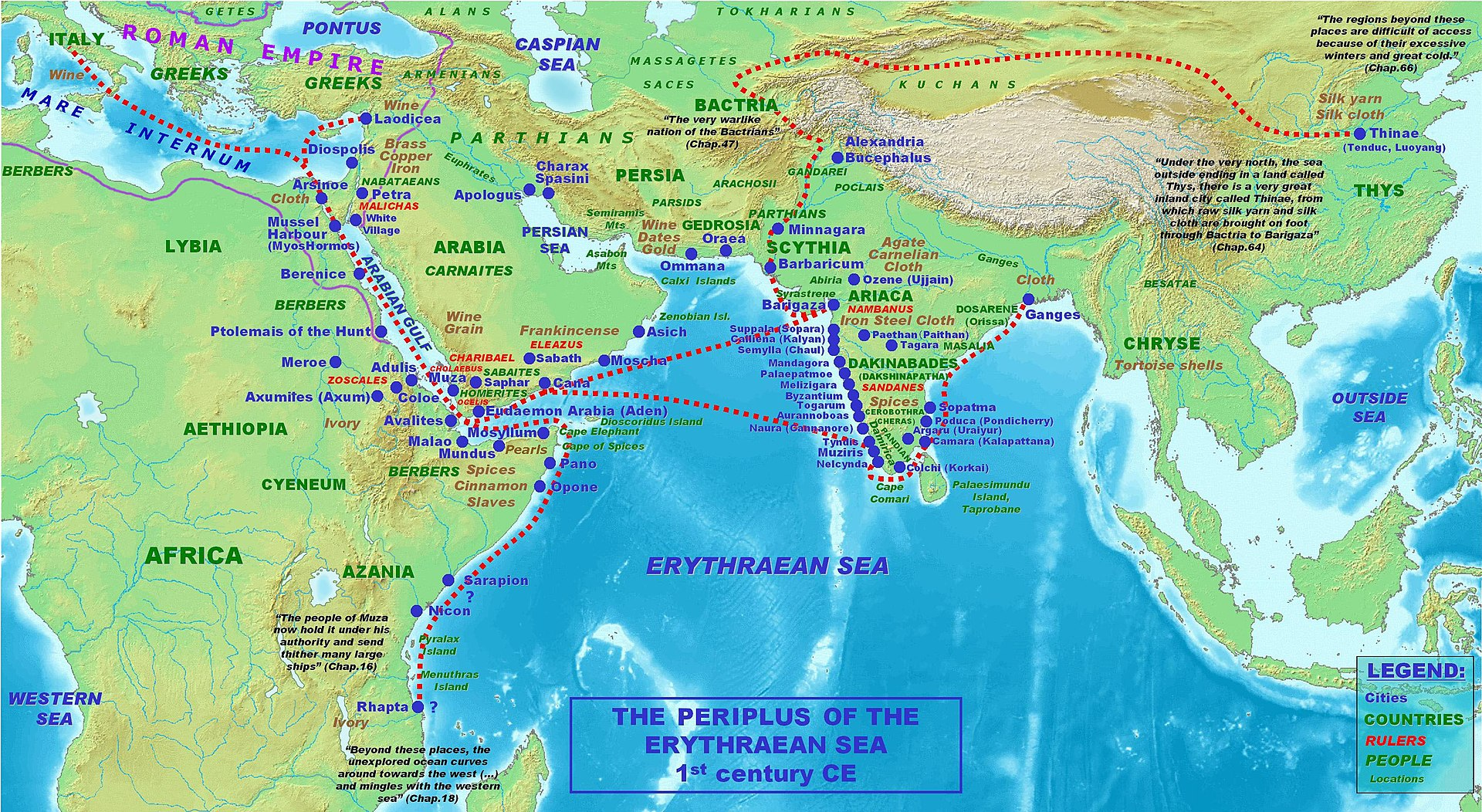

Paithani Weaving and Indo-Roman Trade in Ancient Paithan

During the centuries between 200 BCE and 200 CE, Paithan emerged not only as a political capital but also as a thriving center of commerce. Known for its fine textiles, especially the richly woven Paithani fabric, the town became an important stop on ancient trade routes linking inland India to coastal ports and overseas markets. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a first-century Greek trading manual, refers to Pratisthana as a significant commercial hub connected to other parts of India and the western world.

The most prized product of the region was the Paithani sari, known for its delicate use of gold and silver thread on cotton or silk. Historians note that these garments were so highly valued that Roman merchants exchanged gold for them. In fact, such luxury imports became so popular in Rome that the Senate was eventually compelled to ban their purchase to curb excess spending.

Crafted with extraordinary skill, these textiles were usually reserved for royalty and were considered symbols of status and refinement. The reputation of Paithani weaving continued well into the later periods of history. Even in the 18th century, figures like Peshwa Madhavrao are recorded as admirers of this tradition, which speaks to the long-standing fame of Paithan as a center of luxury and artisanal excellence.

Ajanta and the Spread of Buddhism in the Region

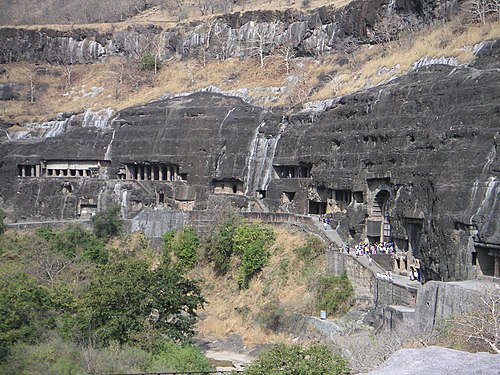

While Paithan was known for trade and fine textiles, another development was taking place not far to the north, one that reflected the region’s growing importance in the religious and cultural life of early India. This was the making of the Ajanta Caves.

The caves are located near the Waghur River, carved into a cliff that curves like a horseshoe. The earliest work at Ajanta began around the 2nd century BCE, during a time when Buddhism was spreading across the Deccan. Monks from the Hinayana tradition began using the site to create simple rock-cut dwellings and prayer halls. These spaces were not meant for large gatherings but rather for quiet living, study, and meditation.

Ajanta's location was not accidental. The site was close to well-travelled trade routes, and this made it easier for monks, pilgrims, and patrons to support the work being done there. The Satavahana rulers, based at Paithan, are believed to have supported many such Buddhist communities by offering them land or grants. In this way, religious activity and trade moved together, shaping the cultural landscape of the region.

By the 5th century CE, the caves had begun to change. During this period, the influence of the Vākāṭakas was spreading across much of present-day Maharashtra, and the region around Sambhaji Nagar came under their control. Under the patronage of the Vakataka kings, especially Harishena, Ajanta entered a new phase of construction. Notably, several inscriptions found at Ajanta record the names, genealogy, and deeds of Harishena’s vassals and ministers, offering rare insight into the administrative and courtly life of the Vakaṭaka period.

This period was linked with Mahayana Buddhism, which allowed for the use of human images of the Buddha and supported elaborate forms of worship. The newer caves were larger and more decorative. They included finely carved stone pillars and detailed wall paintings that told stories from the Jataka tales and legends about the Buddha’s earlier lives. These paintings showed not just religious scenes but also everyday moments, such as people in conversation, musicians, animals, and buildings, which were also painted with color!

The activity at Ajanta seems to have ended by the 7th century. For many centuries, the caves were hidden in the forest and gradually forgotten. They were rediscovered in 1819 by a British officer. Since then, Ajanta has been recognized for its historical and artistic value. In 1983, the site was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.

In many ways, Ajanta provides a clear picture of how Buddhism was practised and supported in this part of the Deccan. It also shows how religion, art, and trade often moved together, each shaping the life of the region in its own way.

Ellora and the Patronage of the Rashtrakutas

While Ajanta saw its final phase around the 7th century, another site nearby was entering its most active period. This was Ellora, located not far from Verul village in the present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district. Over the next three centuries, it developed into one of the most important rock-cut cave complexes in India, notable for bringing together three religious traditions (Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism) within a single landscape.

The earliest caves at Ellora were Buddhist, carved during the 6th and 7th centuries. These included monastic halls and shrines, many of which reflect the influence of the Mahayana school. Large images of the Buddha began to appear, along with sculpted pillars and narrative panels. The design of these caves marked a shift toward more elaborate and expressive spaces, intended not just for meditation but for ritual and teaching as well.

From the 8th century onwards, Hindu Mandirs began to appear at the site. It was during this period that the Rashtrakutas, a powerful dynasty based in the Deccan, became active patrons at Ellora. Among their contributions, the most extraordinary is the Kailash Mandir, a rock-cut mandir dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv, which is said to have been commissioned by King Krishna I. The Baroda inscription of 812 CE, most notably, references that this “great edifice was built on a hill by Krishnaraja at Elapura,” with Elapura being a name scholars associate with Ellora.

The scale and ambition of the project are difficult to overstate. This temple was carved from a single piece of rock, top-down, and designed to represent Mount Kailash, which is believed to be the home of Bhagwan Shiv in Hindu traditions. The work involved removing thousands of tons of stone and required both engineering skill and artistic vision. The result was a multi-story structure complete with inner shrines, open courtyards, and detailed sculptures of devis and devtas, animals, and epic stories. Nothing quite like it had been attempted before, and even today it remains a point of admiration for visitors and scholars alike.

Later, in the 9th century, Jain craftsmen added their own group of caves to the site. These are fewer in number but noted for their delicate carvings and calm interior spaces. Their presence at Ellora suggests that Jainism, too, was gaining followers and patronage in the region during this period, alongside the older traditions of Buddhism and Shaivism.

Devagiri as the Capital of the Seuna Yadavas

By the 12th century, a dynasty known as the Seuna or Yadavas had begun to rise in the western Deccan. They were originally feudatories under the Western Chalukyas, but as Chalukya power declined, the Yadava ruler Bhillama V declared independence around the middle of the century. He shifted his capital to Devagiri, a steep hill-fort located in what is now the Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district.

The fort at Devagiri was not only well-positioned but also naturally defensible. Rising sharply from the surrounding plains, it allowed the Yadavas to control key routes across the Deccan. Over time, they transformed the site into a fortified capital, cutting sheer walls into the rock, building gates at sharp angles, and adding defensive outworks that made it difficult for invading forces to approach unnoticed or unchallenged.

Under Bhillama’s successors, especially Simhana II (reigned c. 1200–1247 CE), the dynasty reached the height of its power. From their base at Devagiri, the Seunas ruled over a territory that stretched from the Narmada River in the north to the Tungabhadra (which flows through the State of Karnataka) in the south. Their domain covered much of present-day Maharashtra, northern Karnataka, and parts of Madhya Pradesh.

During this period, Devagiri grew into a well-established capital, not only of military importance but also as a center of administration, learning, and temple-building. Inscriptions from the Yadava period reflect the use of both Sanskrit and Marathi in royal charters and point to a growing regional identity in the western Deccan.

Sant Nivruttinath, Sant Dnyaneshwar, and Muktabai

Sant Nivruttinath, Sant Dnyaneshwar, and Muktabai were prominent saints, children of Vitthalapant Kulkarni and Rakhumabai, were all born in Apegaon, in Chh. Sambhaji Nagar district of Maharashtra. One of the siblings, Sant Sopan, was born in Alandi. Later on, each of these saints, travelled to various places, followed warkari sampraday and wrote several abhangas in their devotion for Vithhal of Pandharpur.

Medieval Period

The Yadava Capital of Devagiri and Its Fall

At the close of the 13th century, the fortified city of Devagiri, modern-day Daulatabad, stood as the stronghold of the Yadava dynasty in the Deccan. Its strategic location, affluence, and commanding fortifications had long rendered it a center of regional power. Yet it was this very prosperity that attracted the attention of Alauddin Khilji, the ambitious general of the Delhi Sultanate, who in 1296 undertook a bold and unexpected raid deep into the south. This invasion was described by historian Kishori Saran Lal to be the first successful military incursion by a northern Muslim ruler into peninsular India.

The Yadava ruler Ramachandra was caught entirely off guard. Devagiri’s defenses were undermanned, and the king was unprepared for the rapid assault. Seeking to avoid destruction, he negotiated a peace settlement. While Alauddin agreed to withdraw, he imposed a punishing indemnity. Chroniclers describe the scale of loot in astonishing terms. Ziauddin Barani, writing a generation later, claimed that the wealth acquired by Alauddin lasted through the reign of Firuz Shah Tughlaq, over fifty years later. Firishta, a 16th-century historian, provided a more detailed account: 600 mann of gold, 1,000 mann of silver, 7 mann of pearls, 2 mann of rubies, sapphires, diamonds, and emeralds, along with 4,000 silk garments.

As part of the treaty, Ramachandra agreed to divert the revenue of Achalpur province (in present-day Amravati district) to Alauddin. In exchange, the surviving prisoners were released, and Alauddin departed from Devagiri within five days.

The Jhatyapali Narrative and the Question of Royal Alliances

Among the lesser-known but widely circulated traditions of the Devagiri court from this tumultuous period is the tale of Jhatyapali, a daughter of Raja Ramachandra Yadava, whose name appears in varying forms across sources in Chhitai, Jhitai, Jethapali, or Kshetrapali. Though her historicity remains debated, multiple accounts from the 16th to 17th centuries suggest that she played a role in the political entanglements that followed the Delhi Sultanate’s incursions into the Deccan.

According to the historian Firishta, Alauddin Khilji is said to have married Ramachandra’s daughter following the 1296 raid on Devagiri, in a gesture meant to stabilize relations. Other versions, however, claim that Malik Kafur, Alauddin’s general and later viceroy of the Deccan, married her after Alauddin’s death. These contradictory traditions suggest not a single confirmed event, but rather a persistent memory of an alliance, whether real or symbolic, between the Yadava dynasty and the Delhi Sultanate.

The most enduring literary expression of this legend appears in the Hindi poem Chhitai Varta, dated to circa 1440 CE and attributed to the poet Narayan Das. The poem recounts the journey of a princess named Chhitai who, after her father’s defeat, is taken to Delhi and married into the Sultan’s household. Whether the poem reflects a historical reality or merely a cultural allegory remains uncertain. Yet its survival in oral and literary form signals the deep impression left by the Delhi conquest on local traditions.

Malik Kafur’s Reconquest and Yadava Rebellion (1313–1317)

Devagiri remained nominally under Yadava rule following Alauddin Khilji’s raid in 1296, and the kingdom’s tributary obligations to the Delhi Sultanate, in the years to come, were firmly established. However, over time, the arrangement frayed. By 1313, citing non-payment of the agreed tribute, Alauddin dispatched his trusted general Malik Kafur to enforce compliance.

The second expedition was far more decisive. Kafur advanced swiftly and launched an attack that resulted in the death of the ruling Yadava, likely a successor to Ramachandra, and the formal annexation of Devagiri into the Delhi Sultanate. Kafur was appointed governor of the Deccan territories, and from his seat at Devagiri, he oversaw administrative consolidation for the next two years.

However, the arrangement was short-lived. In 1315, Kafur was urgently recalled to Delhi owing to Alauddin Khilji’s declining health. His absence created a power vacuum that the Yadava elite quickly sought to exploit. Harpaladeva, a nobleman widely believed to have been Ramachandra’s son-in-law, seized the moment and declared independence. With the support of his prime minister, Raghava, he reoccupied Devagiri and reestablished a local regime, however briefly.

The rebellion was quickly met with force. On April 13, 1317, Alauddin’s son and successor, Qutb-ud-din Mubarak Shah, led a new military campaign into the Deccan region. According to historian Banarasi Prasad Saksena, most local chiefs in the region submitted to the Sultan’s authority without resistance, with the sole exceptions of Raghava and Harapaladeva. The two rebels were defeated, captured, and executed shortly thereafter.

With this, Yadava political power came to a definitive end, and Devagiri was brought fully under the administrative structure of the Delhi Sultanate.

The Tale of Deval Devi and Prince Khizr Khan

While the political history of Devagiri during the early 14th century is marked by conquest and annexation, a more personal and poignant episode survives from this period. This is the tale of Deval Devi, daughter of Raja Karan Vaghela, the last Rajput ruler of Gujarat, and her fateful union with Prince Khizr Khan, son of Alauddin Khilji.

According to multiple accounts, following the fall of Gujarat in 1299, Deval Devi was sent toward the Yadava capital at Devagiri, where she was to be married into the local royal family—possibly to the son of Raja Ramachandra. However, as her wedding procession passed near the Ellora region (which lies in present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district), she was intercepted by Delhi troops and brought to the Delhi court. There, she eventually became the consort of Khizr Khan, Alauddin’s heir.

The narrative was famously immortalized by Amir Khusrau, the celebrated Sufi poet and court chronicler, in his Persian masnavi Ashiqa. In Khusrau’s retelling, Deval Devi and Khizr Khan are portrayed as star-crossed lovers, caught between dynastic duty and personal emotion. Their union, in this view, becomes a symbol of cultural fusion and tragic romance, set against the backdrop of Delhi’s expanding empire.

The story gained renewed attention centuries later through the Gujarati historical novel Karan Ghelo (1863) by Nandshankar Mehta, which retells the fall of the Vaghela dynasty with a critical lens. In Mehta’s version, Raja Karan’s political missteps and his inability to protect Deval, are seen as emblematic of princely decline. The title itself, Karan Ghelo (“Karan the Foolish”), underscores the moral judgment embedded in the narrative.

Daulatabad as a Short-Lived Capital under the Tughlaqs

With the fall of the Yadavas in the early 14th century, Devagiri became a provincial stronghold of the Delhi Sultanate. But in the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq (1325–1351), the city’s role would change dramatically. In 1327, the Sultan made a bold and controversial decision: he ordered the transfer of the Sultanate’s capital from Delhi to Devagiri and renamed the city Daulatabad, meaning “City of Fortune.”

This was no ordinary administrative shift. The Sultan’s goal was to establish a central seat of power that could better control both northern and southern India. Devagiri’s location, far from the political intrigues of Delhi and closer to the new conquests in the Deccan, was seen as ideal. The change was sweeping. Officials, nobles, craftsmen, and large sections of the Delhi population were ordered to migrate to the new capital. Yet the grand experiment soon proved unsustainable.

Many are said to have perished during the forced migration, and those who survived struggled to adapt to the unfamiliar landscape. The logistics of governance suffered, and within a few years, the capital was quietly shifted back to Delhi. But the episode left a lasting imprint on the city and on the district’s place in history.

The Daulatabad Mint

During his time here, Muhammad bin Tughlaq introduced many major reforms. One of these was the use of token currency. In 1329, according to the colonial district Gazetteer, a mint was established at Daulatabad to produce copper and brass coins known as tankas, which were meant to represent equivalent values in gold and silver. The idea, though innovative, quickly collapsed. The coins were easy to forge, and counterfeit currency flooded the markets. Inflation soared, and trade suffered. The Sultan was forced to withdraw the scheme. For years afterwards, the remains of these fake coins were said to lie in heaps outside Daulatabad Fort, a lasting reminder of the failed experiment.

Himroo Fabric

Despite these troubles, the period saw the arrival of skilled artisans and weavers who had migrated along with the Sultan’s entourage. Among their legacies was a distinctive textile craft known as Himroo. The term comes from the Persian hum-ruh, meaning “similar” (referring to its resemblance to royal silk brocade). Himroo fabric, woven from a blend of local cotton and silk, featured intricate floral and geometric motifs inspired by Persian designs. Though the capital eventually returned to Delhi, many of the weavers chose to remain in Daulatabad, making the city a center for textile craftsmanship.

Mentions in the Travels of Ibn Battuta

In 1334, the famed Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited the city. His writings offer a rare glimpse into Daulatabad at the height of its splendor. He described a thriving bazaar filled with music, dancing, and colorful fabrics. The city’s pleasure district, known as Tarababad, which literally means “the place of joy,” captivated him with its lively atmosphere. To Battuta, Daulatabad was not only a formidable fortress but also a flourishing cultural center.

Fragmentation of the Sultanate and the Rise of Malik Ambar

In the decades following Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s retreat from the Deccan, the Delhi Sultanate’s grip on the region weakened. By 1347, its Deccan provinces had broken away entirely, and a new state, the Bahmani Sultanate, emerged under Alauddin Bahman Shah, with its capital first at Gulbarga and later at Bidar. While no clear evidence places Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district directly under early Bahmani administration, the broader region remained within the political orbit of the new sultanate.

The Bahmani state eventually fragmented, and in 1490, one of its provincial governors, Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I, declared independence. He established the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, with its initial power base not far from present-day Aurangabad. Within a few years, the city of Daulatabad, formerly the Tughlaq capital, was absorbed into this expanding kingdom.

At the turn of the 17th century, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate came under the de facto leadership of a remarkable figure: Malik Ambar. Born in Ethiopia and sold into slavery as a child, Ambar rose through military ranks to become the most powerful statesman in the Deccan. A brilliant tactician and astute administrator, he revitalized the Sultanate during a period of Mughal pressure and internal instability.

In 1610, Ambar founded a new city near Daulatabad called Khadki, which would later evolve into Aurangabad (see more on it below). Designed with fortified walls, planned roads, and civic infrastructure, Khadki was conceived as both a military base and an administrative center. It was during his tenure that the weavers and artisans who had once migrated to Daulatabad during Tughlaq’s reign found renewed patronage. The production of Himroo fabric, already established in the region, expanded significantly under his rule.

Later, Ambar’s son, Fateh Khan, succeeded him and renamed the city Fatehnagar, giving it a new identity while continuing its role as the capital of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. This renaming marked a brief transition before the region once again shifted hands—this time, into the expanding territory of the Mughal Empire.

Sant Eknath

Sant Eknath made a profound contribution to Marathi spirituality by acting as a bridge between the philosophy of Sant Dnyaneshwar and the mass devotion of Sant Tukaram. He was born around 1533 in Paithan (now in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district), a revered scholar and poet of the Warkari tradition.

Under the guidance of his Guru, Janardan Swami (a devotee of Dattatreya), he mastered both spiritual and worldly duties. His entire life and karmabhoomi were centred in Paithan.

Sant Eknath’s greatest social reform was his radical challenge to caste discrimination. He famously practised Bhagavat Dharma (seeing God in all beings) by dining with the "untouchables" and showing compassion to all, which angered the orthodox Brahmins of his time. He popularised philosophy through a unique folk-art form called Bharud, a dramatic and musical song that delivered spiritual messages. He also edited and standardised the definitive version of the Dnyaneshwari and wrote the Eknathi Bhagwat, making profound spiritual knowledge accessible to every level of society.

Mughal Consolidation and the Deccan Headquarters

By the end of the 16th century, the Mughal Empire, under Emperor Akbar, had begun asserting its dominance over the Deccan. In 1595, the Mughal court demanded that the four Deccan sultanates recognise Mughal suzerainty. When the Ahmadnagar Sultanate resisted, it became the immediate target of military intervention. In 1600, the Mughals captured Ahmadnagar Fort (which lies in Ahilyanagar) and annexed much of the surrounding territory, including Daulatabad and the present-day district region.

As the empire extended southward, the region’s strategic importance increased. In 1636, the young Mughal prince Aurangzeb was appointed viceroy of the Deccan and initially took up residence at Daulatabad. Soon after, he shifted his headquarters to nearby Fatehnagar, the city founded earlier by Malik Ambar’s son. Renaming it Aurangabad (present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar city), Aurangzeb began developing it into a full-fledged administrative and military center.

Aurangzeb’s association with the city would deepen over time. In 1653, after a period in the north, he returned to the Deccan as emperor and reinstated Aurangabad as the imperial headquarters for his southern campaigns. For over two decades, the city served as the base from which Mughal operations across the Deccan were conducted, reshaping the urban and political geography of the region.

The Maratha Presence and Shivaji’s Raids

Although Aurangabad (present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar) had emerged as the principal Mughal base in the Deccan, it remained exposed to the rising force of the Maratha Empire. Under Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the Marathas launched a series of daring campaigns that repeatedly penetrated Mughal-controlled territory, including the environs of Aurangzeb’s Aurangabad itself. Shivaji’s connection to the district was not incidental. His grandfather, Malhoji Bhonsle, had served as a military commander under Malik Ambar and held the jagir of Verul (modern Ellora).

In August 1664, Shivaji plundered Ahmednagar (present-day Ahilyanagar district). His forces then moved toward Aurangabad, causing panic on its outskirts. In response, Emperor Aurangzeb entrusted command to Raja Jai Singh I of Amber, whose military campaign led to the Treaty of Purandar (1665). As part of the agreement, Shivaji agreed to send his son, Sambhaji, to the Mughal court at Aurangabad, accompanied by the Maratha general Prataprao Gujar.

While this temporary settlement held for a brief period, tensions soon reignited. By 1675, Shivaji had resumed his advance into Mughal territory. According to the 1884 District Gazetteer, he once again approached Aurangabad, where his army ravaged the surrounding countryside for three consecutive days. Mughal forces were dispatched from the city to push him back, and a dramatic episode unfolded near Sangamner [in Ahilyanagar district], where Shivaji was nearly captured. He managed to escape through a network of local allies and loyal retainers. Although he passed away in 1680, Shivaji’s raids had fundamentally altered the region’s political balance.

Aurangabad as the Southern Capital of Emperor Aurangzeb

In 1681, now Emperor, Aurangzeb shifted his entire imperial court from Delhi to Aurangabad [Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar], aiming to permanently subdue the Deccan. Though he left the city in 1684, it remained the Mughal Empire’s principal military base in the region until he died in 1707.

By the late 17th century, Aurangabad [Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar] had evolved into more than just a military capital. It had become a vibrant center of Persian and Urdu literature, courtly culture, and spiritual devotion. At its height, the city is estimated to have housed over 2,00,000 inhabitants, making it one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities of the Mughal Deccan.

The Architectural and Sacred Legacy of Aurangzeb

The prolonged presence of Emperor Aurangzeb in the Deccan left a lasting architectural and spiritual imprint on the region. At the heart of this legacy stands the Bibi ka Maqbara, a striking mausoleum located in the Begumpura tehsil of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar city. Commissioned in 1660 by Prince Azam Shah, Aurangzeb’s son, the structure was built in memory of his mother, Dilras Banu Begum, posthumously titled Rabia-ud-Daurani (“Rabia of the Age”).

Intended as a tribute to maternal devotion, the Bibi ka Maqbara echoes the design of the Taj Mahal, though it is more modest in scale and ornamentation. The mausoleum is constructed largely of locally sourced marble and features intricate latticework, carved panels, and a central dome set amidst a formal Mughal garden with flowing water channels. Designed by the architect Ataullah, it blends the architectural grammar of the north with subtle elements of Deccani style. Today, the monument is protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and remains a major symbol of the city’s historical identity.

Aurangzeb’s influence also extended to the sacred landscape of the district. In the nearby town of Khuldabad [approx. 25 km west of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar city, he chose to be buried in accordance with his austere beliefs. His tomb is striking in its simplicity, an unadorned grave under open sky, funded, as per his will, from the sale of cloth caps he had sewn with his own hands. The town itself, historically known as Rauza, meaning “shrine,” became a prominent Mughal burial site and by the late 17th century was referred to as Khuldabad, or the “Abode of Eternity.”

Khuldabad is also the resting place of Malik Ambar, the powerful Ahmadnagar statesman, as well as several Mughal nobles and Sufi saints. The town had long attracted mystics from across the Islamic world, particularly after Muhammad bin Tughlaq shifted his capital to nearby Daulatabad in the 14th century. During Aurangzeb’s rule, the area became a spiritual and funerary center for the empire’s elite.

Nizams of Hyderabad and the Decline of Aurangabad

With the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Mughal Empire began a steady decline. In the Deccan, this vacuum of power gave rise to a new polity. In 1724, Asaf Jah I, also known as Nizam-ul-Mulk, declared independence from the weakened Mughal court and established the Hyderabad State. A seasoned Mughal general and administrator, he retained the title of Subedar of the Deccan but ruled with autonomy.

Initially, the political and administrative center of this new dominion was Aurangabad. The city continued to serve as the capital of the Nizam’s dominion, and its forts, palaces, and administrative structures remained in active use. However, the grandeur and imperial funding that had characterized the Mughal era had already begun to recede.

During this time, the courtly economy began to decline. It is said that military campaigns and factional rivalries drained the state’s resources, and investment in urban infrastructure slowed. Though Aurangabad remained a second city of the new Hyderabad State, it no longer occupied the central place it had enjoyed under Aurangzeb.

Battle of Palkhed, 1728

The newly established Hyderabad State faced challenges from the growing power of the Marathas. A major confrontation took place in 1728 in what is now the Vaijapur taluka of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district. This was the Battle of Palkhed, in which the Maratha forces under Peshwa Bajirao I defeated the Nizam’s army using swift cavalry maneuvers. The battle is notable for Bajirao’s strategic use of encirclement, which outpaced the slower, Mughal-style formations of Asaf Jah I.

Treaty of Mungi Shevgaon, 1728

This victory led to the Treaty of Mungi-Shevgaon, signed later that year. Though the treaty was concluded in present-day Ahmednagar district, its implications directly affected Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar. The Nizam was required to acknowledge the Marathas’ right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi, forms of taxation, across the Deccan. In practice, this meant that the region experienced dual authority, with both Nizam and Maratha agents operating in parallel, often leading to tensions but also periods of cooperation. Revenue collection, land assessment, and local administration became zones of overlapping control.

Relocation of the Nizam’s Capital from Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar

A major political shift occurred in 1763, when Nizam Ali Khan Asaf Jah II, the son and successor of Asaf Jah I, formally transferred the capital from Aurangabad to Hyderabad city (in present-day Telangana). The move was prompted by both strategic concerns and economic opportunities: Hyderabad offered better access to revenue-rich areas and a more defensible geographic position.

For Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, this marked the beginning of a slow but visible decline. According to later British records, the population of the city decreased significantly in the early 19th century, and many administrative buildings fell into disrepair. Nonetheless, Sambhaji Nagar remained the second most important urban center in the Hyderabad State throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

British Alliance and the End of Maratha Influence

The final phase of these centuries, however, saw the decline of Maratha political strength following their defeat in the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761. Though the Marathas had once successfully negotiated with the Nizam and extracted revenue rights in the Deccan, these arrangements did not survive the changing political climate.

During the Second (1803–1805) and Third (1817–1818) Anglo-Maratha Wars, the British East India Company dismantled the Maratha Confederacy. The Nizam, having sided with the British, gained politically from this outcome. The tax rights previously granted to the Marathas were annulled. By 1818, chauth and sardeshmukhi collections ceased in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district, and the region came fully under the administrative authority of the Nizams of Hyderabad.

Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountacy

At the turn of the 19th century, the East India Company (EIC) consolidated its presence in the Deccan through a series of strategic treaties. Chief among these was the Treaty of 1800, concluded with the Nizam of Hyderabad, which brought vast tracts of territory, including the present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district, under the practical control of the British without direct annexation.

Under the terms of this subsidiary alliance, the Nizam ceded territory instead of maintaining a British-controlled subsidiary force. This allowed the British to garrison troops in key locations across the Nizam's dominions. A major cantonment was established in Aurangabad (present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar) in 1816, from which the British oversaw the surrounding region while maintaining the formal sovereignty of the Nizam. Although the territory remained legally part of the Hyderabad State, its governance increasingly reflected British military and administrative preferences.

During this period of indirect British rule, internal affairs remained under the authority of the Nizam and his officials. One of the most influential figures in this arrangement was Raja Chandu Lal, who served as the Prime Minister of Hyderabad State from 1833 to 1844. The district Gazetteer (1977) mentions that the British authorities found significant support from Chandu Lal, and it was through his influence that the contingent, known as the Hyderabad Contingent, was sanctioned in Hyderabad under the command of British officers.

Local Resistance and the Bhil Uprisings

Not all accepted this new order quietly. From the early 1820s, the forested and hilly tracts to the north and west of the district, particularly around Ajanta, became the scene of fierce resistance led by local Bhil communities. These groups, long accustomed to relative autonomy, viewed British incursions and the tightening of revenue policies as intolerable disruptions.

Of the early leaders, the district Gazetteer (1977) mentions the figures of Chil Naik, Jandhula, and Jakira, who galvanized opposition to the Hyderabad Contingent's presence in the hills surrounding Ajanta and Ambad. They became notorious for ambushing British patrols and disrupting administrative control. Their familiarity with the rugged terrain made suppression difficult. British military expeditions were repeatedly dispatched into the Ajanta ranges, and several temporary cantonments were erected in an attempt to secure the area.

It is noted that the British were compelled to deploy troops for six months to subdue the region, eventually appointing a Bhil Agent to monitor local tensions. Attempts were made to co-opt the Bhils into the Bhil Corps and settle them into agricultural routines, but resistance persisted in varied forms until the mid-19th century.

The First War of Independence, 1857

When the great revolt of 1857 broke out across northern and central India, its tremors reached the Deccan region as well. Though the Nizam of Hyderabad remained loyal to the British, discontent within his army was harder to contain. One of the most significant episodes in this region occurred in present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, where the 1st Hyderabad Contingent mutinied in June 1857.

The revolt unfolded between 9 and 19 June, centered around the Kham River and the area now known as Kranti Chowk. Contemporary accounts and local memory suggest that the uprising drew inspiration from the broader rebellion led by Peshwa Nana Saheb and Tatya Tope. In response, British officers, including Captain Abbott, then stationed at Nashik, and General Woodburn, operating within the district, arrived to quell the disturbance.

The reprisals were swift and severe. Twenty-four sepoys were court-martialed. One among them, Head Constable Amir Khan, attempted to shoot Captain Abbott but missed. Three rebels were executed by cannon fire at Kranti Chowk, while the remaining twenty-one were hanged at a location later called Kala Chabutra, literally “Black Platform.” Over time, this site would come to be remembered as one of the earliest symbols of sacrifice in the district’s participation in the freedom struggle.

Anant Laxman Kanhere and Revolutionary Networks

In the decades that followed, nationalist sentiments continued to grow in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, despite the region’s formal inclusion in the princely Hyderabad State. The Swadeshi movement, launched in response to the 1905 partition of Bengal, found active support among residents of the district. Local newspapers reflected the mood of protest, while public meetings and student-led demonstrations became increasingly common.

The influence of Bal Gangadhar Tilak was strongly felt during this period. Though not from the region, Tilak’s ideas and political message spread widely across the Deccan. In 1908, his arrest sparked student protests in the city. At this time, one of the most significant revolutionary networks operating in the district was a local secret society founded by Gangaram Marwadi. This group maintained links with a larger circle of revolutionaries based in Nashik. Among its members was Anant Laxman Kanhere, originally from Ratnagiri, who had come to study at the Arts School in Sambhaji Nagar. It was during his time in the city that Kanhere became involved with political circles and committed to the cause of Indian independence.

Kanhere would later go on to assassinate A.M.T. Jackson, the British Collector of Nashik, in 1909. While this act took place outside the district, the planning and ideological groundwork were laid during his time in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar.

Birth of Cotton Industry, 1889

In the late 19th century, industrial activity began to grow in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, most notably with the founding of the city’s first cotton mill in 1889. Situated in the heart of the Deccan plateau, the district benefited from fertile black soils conducive to cotton cultivation, and the emergence of textile manufacturing was a natural corollary. Several ginning and pressing factories were established in quick succession, further consolidating the city’s position as an industrial center.

Yet this period of progress was not without interruption. The famines of 1899–1900, followed by those of 1918 and 1920, severely affected agricultural output and labor conditions. Nevertheless, the cotton industry endured and, in later decades, continued to form the backbone of the district’s manufacturing sector.

Development of Railway Communications

The need to support expanding cotton trade and agricultural surplus brought attention to transportation infrastructure. In 1900, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar was connected by rail through the Hyderabad–Manmad line, built under the Godavari Valley Railway Company, a subsidiary of the Nizam’s Guaranteed State Railway.

Preliminary groundwork for this line had begun under Mir Mahbub Ali Khan, the 6th Nizam of Hyderabad, with the construction of a line from Hyderabad to Bezwada (Vijayawada) in the 1870s. By 1885, the broad-gauge line between Secunderabad and Wadi had been completed. These developments laid the foundation for connecting the interior Deccan to major port cities and trade corridors.

The Hyderabad–Manmad line, completed in 1900, greatly improved the movement of cotton and other goods from Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar to broader markets. A meter-gauge extension between Hyderabad and Jaipur was added in 1906, expanding the city’s connectivity further.

After India’s independence, the Nizam’s railway network was nationalized in 1950. The Secunderabad–Manmad line, passing through Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, was converted to broad gauge in 2004, bringing the district fully within the ambit of India’s modern railway network.

Post-Independence

Following the end of British rule in 1947, the district of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar entered a period of political transition and reorganization, which was shaped by its inclusion within the princely State of Hyderabad. Unlike provinces directly governed by the British Crown, Hyderabad posed a unique constitutional challenge during the integration of Indian states. Governed by the Nizam, whose administration was largely Muslim, the state contained a Hindu-majority population and initially resisted accession to either India or Pakistan. This impasse culminated in Operation Polo, also referred to as the “Police Action,” launched by the Government of India in September 1948. The operation resulted in the swift annexation of Hyderabad into the Indian Union, thereby bringing the Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district under the jurisdiction of the Republic of India.

For nearly eight years thereafter, the district remained part of the Hyderabad State under Indian administration until the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which realigned internal boundaries on linguistic grounds. Consequently, the district was transferred to the bilingual Bombay State. A further reorganization in 1960, which saw the creation of linguistic states, led to its incorporation into the newly formed State of Maharashtra. Since then, the district’s political and administrative development has unfolded within the framework of Maharashtra’s governance structures. In recent decades, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar has been included in the Government of India’s Smart Cities Mission.

Sources

Abhinav Agarwal. 2015. The Maratha Military Genius: The Battle of Palkhed. Indiafacts.http://indiafacts.org/the-battle-of-palkhed/

Aravinda Prabhakar Jamkhedkar. 2009. Ajanta. Oxford University Press.

Deepali Susar. 2022. बारा ज्योतिर्लिंग: घृष्णेश्वर मंदिराचा नेमका इतिहास काय आहे ?. Esakal.https://www.esakal.com/culture-and-religion/…

Government Of India. 2023. Participation of Aurangabad in First War of Independence. Digital District Repository.https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/district-reopsi…

Government of Maharashtra. 1977. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Aurangabad District.Gazetteers Department, Mumbai.

Maharashtra Times. 2021. पैठणीचा रुबाब! साड्यांची महाराणी पैठणीचा 'हा' इतिहास माहीत आहे का? वाचा सविस्तर.https://maharashtratimes.com/lifestyle-news/…

Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). Vol. 5 (Second ed.). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House.

N.N Mahapatra. 2016. Sarees of India. Woodhead Publishing India Pvt. Limited.

P. R. Srinivasan. 2007. Ellora. Archaeological Survey of India.https://books.google.com/books?id=b8UOAQAAMA…

Sudheer Maurya. 2014. Deval Devi: Ek Aitihasik Upanyas.

The Nizams Government. 1884. Gazetteer of Aurangabad. Times of India Steam Press, India.

Tulsi Vatsal and Aban Mukherji. ‘Karan Ghelo’: Translating a Gujarati classic of love and passion, revenge and remorse. Scroll.https://scroll.in/article/764549/karan-ghelo…

Walter M Spink. 2007. Ajanta: History and Development, Volume 5: Cave by Cave. Brill.

WeaveinIndia. Paithani.https://www.weaveinindia.com/collections/pai…

Wikipedia Contributors. Banarsi Prasad Saksena. Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banarsi_Prasad…

Wilfred Harvey Schoff tr. 1912. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea; travel and trade in the Indian Ocean. New York [etc.] Longmans, Green, and Co.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.