DHARASHIV

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Dharashiv’s architectural landscape reflects the layered transitions of religious, political, and cultural influence across two millennia. From early brick and rock-cut constructions to fortified complexes and masonry domes, the region offers rare and enduring examples of evolving styles in the Deccan.

The Trivikrama Mandir in Ter stands as one of Maharashtra’s earliest surviving brick structures, revealing transitions from Buddhist to Vaishnava forms. The nearby Dharashiv Caves map shifts across Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu patronage through their carved basalt interiors. Later structures like the Hemadpanthi mandirs at Mankeshwar and Umarga display local craftsmanship and regional variations shaped by the Chalukyas, Silharas, and Rashtrakutas. The fortified hilltop complex of Tulja Bhavani Mandir reflects a mix of architectural and dynastic influences, while the sprawling Naldurg Fort represents Indo-Islamic military design. The dome of Hazrat Khwaja Shamsuddin Ghazi Dargah marks Dharashiv’s place in the architectural networks of the Tughlaq era. Together, these sites highlight Dharashiv’s role as a crossroads of stylistic exchange and architectural adaptation in the Deccan.

Naldurg Fort

Naldurg Fort is a large medieval stone fort located in the Dharashiv district, built in the Indo-Islamic architectural style. The fort holds significant historical importance as one of the largest land forts in Maharashtra, strategically situated on the banks of the Bori River. It is believed to have been constructed by King Nal (circa 250-500 CE), with major additions and renovations undertaken during the 16th century under the Adilshahi Sultanate. The fort served as a critical military stronghold, playing an essential role in the defense of the Deccan region.

The fort’s design incorporates defensive features characteristic of Indo-Islamic architecture. It is surrounded by thick, high stone walls, some of which rise to over 50 ft. in height, providing a formidable defense against invaders. The fort is distinguished by 114 watchtowers, including the Upli Buruj and Paranda Buruj, which rise to 100 ft. These towers, strategically placed, allowed for surveillance and the deployment of artillery, offering a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape. The fort also boasts an intricate system of gates and bastions, designed for both defense and visual impact.

A unique feature of the fort is its natural moat, formed by the Bori River, which encircles the fort, providing an additional layer of protection. The Hulmukh Darwaza, the main entrance, is characterized by a narrow, long passage protected by multiple doors, as well as elevated platforms and intricately designed pillars. This approach ensures the fort’s defensibility while also demonstrating the sophisticated military architecture of the time.

Inside the fort, several notable buildings reflect a blend of military and royal architecture. The Jama Masjid, a mosque within the fort, showcases a blend of Indo-Islamic styles with ornate arches, domes, and carvings. The Rang Mahal and Gandhak Mahal, once royal residences, feature grand halls with high ceilings, large windows for ventilation, and courtyards surrounded by columns. These structures combine practical military design with the lavishness expected of royal architecture, illustrating the fort’s dual purpose as both a military bastion and a royal residence.

Another striking feature of Naldurg Fort is the Pani Mahal, a water-based structure that contains a dam to control the flow of the Bori River. This dam and its cascading water channels not only provided a strategic water source for the fort but also contributed to its aesthetic appeal, with water flowing through canals into the fort's courtyards and gardens. This architectural element further emphasizes the fort's blend of defense and beauty.

The design of Naldurg Fort is a testament to the advanced military engineering of the period, combining functional defensive structures with royal and ornamental elements. The fort’s intricate planning and the inclusion of water management systems reflect the technical sophistication of the Indo-Islamic style of architecture in the Deccan Sultanate era.

Trivikrama Mandir

Trivikrama Mandir in Ter, Dharashiv district, follows the apsidal or Hastiprishtha (elephant-back) architectural style and is widely regarded as the oldest standing brick Mandir in Maharashtra. The Mandir is dedicated to Devta Vaman, a form of Bhagwaan Vishnu, but its architectural form suggests earlier religious affiliations. Scholars believe it was built between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE, likely under the Satavahanas.

The Mandir consists of a rectangular shrine with an apsidal end and a square mandap (pillared hall). The shrine is made of thick bricks, and its roof is a brick-built, wagon-vaulted, corbelled structure. The mandap has a flat roof supported by wooden pillars with turned capitals and constricted necks. A pointed arched entrance, resembling a chaityagriha (prayer hall) arch, rises 17 ft. above the mandap and reflects strong Buddhist stylistic influence.

Archaeologists such as Henry Cousens (1903) and James Fergusson (1899) have suggested that the original structure was likely a free-standing Buddhist chaityagriha, based on its apsidal layout and chaitya-arch facade. Later adaptations, including the addition of the flat-roofed mandap and the placement of a Trivikrama murti in the garbhagriha (sanctum), likely occurred during the early Chalukya period. Decorative features include stucco pilasters with roll moldings and non-uniform brickwork in the mandap, indicating various construction phases.

The Mandir’s form closely resembles early Buddhist architecture, including structures from Taxila (30 BCE–50 CE), and shows stylistic parallels with early Pallava mandirs of the 7th century CE. Scholars have proposed different dates for the Mandir’s construction, ranging from the Satavahana to the early Chalukya period, depending on whether they emphasize structural technique or iconographic content.

The Trivikrama Mandir is notable not just for its religious significance but also for its survival as a rare example of early brick mandir architecture in Maharashtra.

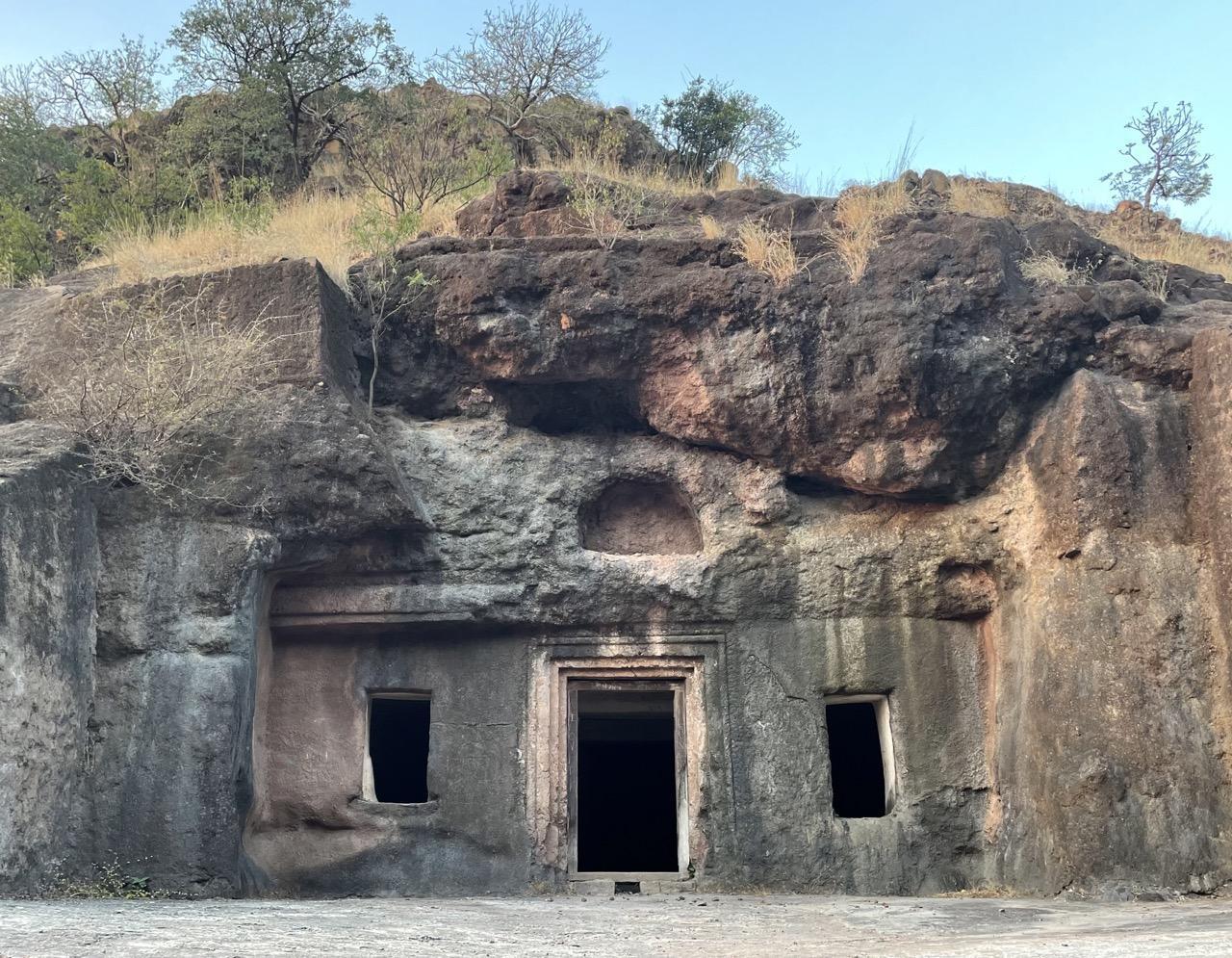

Dharashiv Caves (Leni)

The Dharashiv Caves follow the rock-cut architectural style and are carved into a basalt hillside around eight km from Dharashiv town. The site comprises seven caves arranged unevenly along a slope, each reflecting architectural elements associated with Buddhism, Jainism, and later Hinduism. The caves date to the 5th–10th centuries CE and represent a layered religious history in the Deccan.

Caves 1 through 3 feature Buddhist architectural components such as a chaityagriha, viharas (monastic cells), and a garbhagriha with a seated sculpture of Gautama Buddha in padmasana (lotus pose). One cave is believed to be modelled after the Ajanta caves and is likely from the Vakataka period (circa 250–550 CE). The initial excavation is generally dated to the 5th century CE, possibly during or after the Satavahana period.

Caves 4 through 7 display Jain architectural features, including sculpted figures of Tirthankaras and ornate stone detailing, likely added under the Rashtrakuta dynasty (circa 8th–10th century CE), which patronized Jain and Hindu architecture. Minor Hindu carvings appear in some sections, indicating reuse or adaptation in later periods. The site's stylistic parallels with Ajanta and Ellora suggest Dharashiv’s inclusion in a wider monastic network in the early medieval Deccan.

The caves are accessed by stone steps leading down from the main road and are surrounded by seasonal vegetation. During the monsoon, small water pools called Malrana form naturally in the area. Though lesser known than other cave sites, the Dharashiv Caves offer insight into the religious, architectural, and cultural shifts of the region.

Shiv Mandir, Mankeshwar

The Shiv Mandir at Mankeshwar follows the Hemadpanthi style of mandir architecture and is located on the banks of the Vishwakarma River in Dharashiv. Built from a single block of black stone, the Mandir follows a distinct star-shaped layout, with a curved outer wall that stands out from typical linear plans. The Mandir is east-facing, and its entrance opens directly onto the riverbank.

Shiv Mandir, Umarga

The Shiv Mandir at Umarga is a nearly 1,000-year-old mandir built around the 11th century in the Hemadpanthi style, located in the Dharashiv district. Architectural details suggest influences from the Chalukya, Silhara, and Rashtrakuta dynasties. The Mandir stands on raised ground and features an entrance framed by elephant carvings at the base of the stone pillars.

The lower walls of the Mandir feature intricate carvings of devis, devtas, and elephants, likely representing scenes from epics. The Mandir’s design, including its use of local stone and decorative detailing, reflects both religious devotion and regional craftsmanship.

Tulja Bhavani Mandir

The Tulja Bhavani Mandir in Tuljapur, located on the slopes of the Balaghat range in Dharashiv district, is one of Maharashtra’s four major Shaktipeeths. Built in the Hemadpanthi style, the Mandir is dedicated to Tulja Bhavani, a fierce form of Devi Durga deeply revered across the region. The Mandir holds religious, cultural, and political significance, especially in Maratha history.

Tulja Bhavani Mandir is believed to have been constructed in the 12th century CE by Mahamandaleshwar Maraddev (Mahadev) Kadamb. The Mandir is still managed by descendants of the Kadamb Bhope clan. The structure stands on a fortified hill and is entered through the Sardar Nimbalkar Gate, the main gateway. Two other entrances, Shahaji Gate and Jijabai Gate, are named after Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s parents, reflecting the site’s historical link to the Maratha dynasty.

The Mandir complex includes devsthans dedicated to Markandeya Rishi, Siddhi Vinayak, Aadishakti Matangadevi, Annapurna, and Bhagwaan Dattatreya. A notable feature inside the complex is the ‘Kallola Tirth,’ a large stone tank built in the 14th century. Local legends connect its waters to the Ganga and credit its creation to Bhagwaan Brahma. People often bathe in this tirth, believing it can cure ailments and purify the body before darshan.

To reach the main Mandir, people descend a series of steps after entering through the main gate. A yagna kund (holy fire pit) is located in front of the garbhagriha.

Hazrat Khwaja Shamsuddin Ghazi Dargah

Hazrat Khwaja Shamsuddin Ghazi Dargah in Khwaja Nagar, Dharashiv, follows Islamic architectural traditions and is distinguished by its large central dome, believed by many to be the largest of its kind in the Marathwada region. It is believed that the structure was built by a king from the Maldives, while another view holds that the dargah was a gift from Tughlaq Badshah, founder of the Tughlaq dynasty, in the 14th century. Oral tradition suggests the dargah was constructed by Iranian craftsmen and is around 715 years old.

The structure features a square base with arched entrances on multiple sides, leading into a central chamber capped by a high masonry dome. The inner walls of the dargah are decorated with detailed glass inlay work, added in 2004 by local artisan Gulbar Mistry. These mosaics, composed of colored glass set into geometric and floral patterns, enhance the spiritual atmosphere of the inner sanctum.

The dargah is named after Khwaja Shamsuddin Ghazi Baba, a revered figure known for his spiritual wisdom and, according to local tradition, military prowess. Over the centuries, the site has remained significant for the local community and continues to be maintained by a family of caretakers who trace their lineage to the dargah’s earliest patrons.

Paranda Fort

The fort is rectangular in plan, measuring approximately 235 by 190 meters, and is enclosed by two layers of fortification walls constructed using dry rubble masonry, bricks, and mud. The outer walls are surrounded by a moat or ditch, designed to slow down enemy advances. The moat system included both dry and wet moats, depending on the seasonal availability of water. The walls are reinforced with 26 circular bastions placed at regular intervals, offering strongholds for defense and artillery placement. The inner walls rise higher than the outer ones, following a concentric planning style to enhance protection. The lower portions of the fort walls were built over natural rock formations, providing resistance against siege weapons such as battering rams and war elephants.

Several entrances are dispersed across the fort, with none identified as the primary gate, a deliberate strategy to confuse attackers. Most gates are aligned to avoid direct exposure to harsh sunlight, wind, and rain, with the main ones facing north. These gateways were constructed high and wide to allow elephants to pass and were often fitted with iron spikes to prevent break-ins. Internally, the fort has a dense network of narrow, layered passageways and underground tunnels on the east, west, and south sides that lead to the exterior, used during retreats or attacks.

The fort’s ramparts provided watchpoints for monitoring enemy activity. Features like machicolations, such as box-type structures projecting from the walls and supported on brackets, allowed defenders to drop projectiles on enemies approaching the base. One of the most distinctive external features is the maat or khadak, an embankment-like extension of the defensive wall that integrates the bastions with the terrain beyond.

Within the fort, a variety of structures illustrate both its military and administrative functions. These include the Muhafiz Khana or record room, used for storing land revenue and legal documents, and the Nagarkhana, acoustically designed to amplify announcements and ceremonial music. The watchtower allowed surveillance of the surrounding plains, while storage facilities such as tabelakhana and hathikhana were used to house horses and elephants during wartime. The ammunition depot was centrally located for easy military access.

Water management was also a key component of the fort’s design. There are five baravs (stepwells) within the premises, two of which are connected to external areas via underground tunnels. These water bodies ensured a reliable water supply during sieges. Internal water channels and storage points were planned with great care to support long-term habitation during conflict.

Paranda Fort is also notable for its religious and cultural structures. It contains two mandirs and four masjids, constructed at different times. One of the masjids inside the fort, the Jami Masjid, is said to have been visited by the Nizams for prayer. Its design includes a 27-bayed prayer hall and a domed Hamam or bath chamber. Many Islamic buildings in the fort were converted from earlier Hindu mandirs, as was common in medieval times. The mihrab replaced mandir niches, and original trabeated pillars from the Yadava or Hemadpanti style were retained in modified layouts. The mandirs, too, reflect a fusion of Islamic and Hindu architectural elements, such as domes replacing traditional shikharas and decorative merlons on the roofline.

Paranda Fort stands out for its multi-layered defense, hidden tunnels, integrated civil infrastructure, and vernacular building materials. Its design reflects a masterful blend of functionality and resilience, making it a rare and regionally unique example of medieval military architecture in Maharashtra.

Sources

Durgbharari. Naldurg. Durgbharari. https://durgbharari.in/naldurg/

H Cousens. 1903. Ter.-Tagara, Archaeological Survey of India 1902-03.

Indian Temples. 75 LESSER KNOWN ANCIENT TEMPLES IN INDIA. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/indian.temples/p/C…

Loksatta. 2024. Come to Ter to See the Temple of One and a Half Thousand Years Ago – The 4th Century Trivikram Temple Will Get Its Past Glory. Loksatta, Maharashtra.https://www.loksatta.com/maharashtra/dharash…

M.S. Mate. 1957. The Trivikrama Temple at Ter. Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, Vol. 18, Taraporewala Memorial Volume.

Maharashtra District Gazetteers. 1972. Osmanabad District. Government of Maharashtra.

Maharashtra Tourism, Government of Maharashtra. Naldurg. Maharashtra Tourism. https://maharashtratourism.gov.in/fort/naldu…

Shilpa Dhawale and Supriya Nene. 2024. Analysis Of The Case Study Naldurga Fort, "Fortified Legacy: Deccan, Architecture, And Politics Of Late Mediaeval Forts". Educational Administration Theory and Practices. 30. 10.53555

Shreyas Paranjape. 2021. Medieval Land fort typology of Marathwada region case of Paranda. ResearchGate.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364…

The Temple Guru. Tulja Bhavani Temple. The Temple Guru. https://thetempleguru.com/listing/tulja-bhav…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.