Contents

- Ancient Period

- Stone Age Habitation in the Kan River

- Chalcolithic Life and Harappan Connections at Kaothe

- Dhule as Part of the Ancient Rasika

- Abhiras and the Bhamer Fort

- Sendrakas and Early Epigraphic Mentions of Pimpalner

- The Yadavas and Hemadpanthi Mandirs

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate

- Rise of the Bahmani Sultanate and Establishment of Farooqi Rule in Dhule

- Malik Raja and the Early Farooqi Seat in Thalner

- Nasir Khan & Burhapur as the New Capital

- Tombs of Farooqi Rulers

- Mughal Rule in Dhule

- Maratha Expansion and the Role of Balaji Balwant

- Ahilya Barav and Holkar Influence

- British Conquest and the Fall of Thalner Fort (1818)

- British Annexation and the Development of the Dhulia Town

- Colonial Period

- Dhule as a District Headquarters

- Trade and Agricultural Economy

- The Flood of 1872

- Railway Extension and Communication

- Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade & the Sanshodhan Mandal

- Post-Independence Period

- Sources

DHULE

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

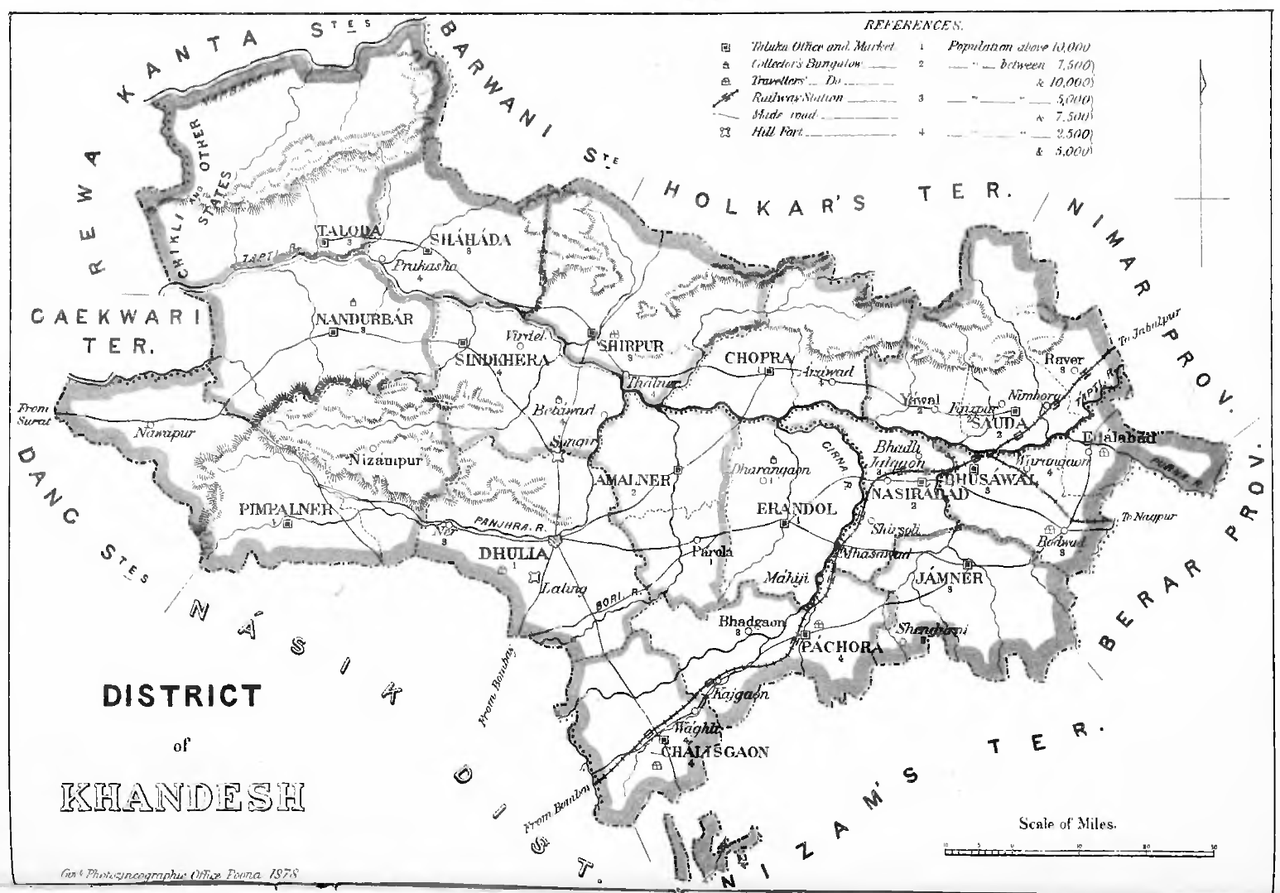

Dhule district (formerly known as Dhulia) is situated in the northern reaches of Maharashtra and forms part of the present-day Nashik Division. Historically, the region was an integral part of West Khandesh, itself a subdivision within the larger administrative framework of the Bombay Presidency during British colonial rule. The district, as an administrative unit, came into being in 1818 following the establishment of British authority in the Deccan.

Yet the region’s significance long predates these relatively modern boundaries. Archaeological evidence attests to continuous human settlement since prehistoric times, and by the early historic period, Dhule had emerged as a seat of power. The Ahirs are believed to have ruled in early times, followed by the Farooqi dynasty, which established its first capital at Thalner, a fortified settlement on the banks of the Tapi River in Dhule district.

Ancient Period

Stone Age Habitation in the Kan River

Dhule has long been a site of human settlement, with a history that stretches back to the prehistoric period. The earliest traces of habitation in the region can be found along the banks of the Kan River, a modest tributary of the Panjra, which itself joins the Tapi. Though the Kan is a relatively small stream, it flows through a valley that has preserved archaeological traces dating back to the Stone Age.

Between 1962 and 1964, a series of surface explorations by archaeologist R.S. Sali identified key sites near the villages of Bhadne and Yesar in Sakri taluka of the district. Numerous stone tools were recovered here, many fresh, others weathered but largely intact, belonging to the Early and Middle Palaeolithic periods. These findings pointed to repeated occupation over time. Later, an excavation at Bhadne in 1965 uncovered nearly 13 metres of sediment, although only a handful of artefacts were found in the trenches themselves. Still, the material gathered through surface collection suggests that the Kan valley had long attracted early human groups, likely due to its perennial water, basalt-rich terrain, and sheltered position.

Chalcolithic Life and Harappan Connections at Kaothe

Another glimpse into Dhule’s long history comes from the site of Kaothe, located just west of Sakri town, which is, notably, recognised as one of the most important Chalcolithic sites in the Tapi valley. Situated on the banks of the Kan River, Kaothe was first reported in 1968 as a Late Harappan settlement, and later excavations confirmed this identification. Dated to around 1800 BCE, the site represents a period when the Harappan world was already in decline, and communities had begun migrating inland from Gujarat in search of more secure and sustainable environments.

Kaothe is remarkable not just for its size (as it spreads across roughly 14 hectares) but for its cultural links. The pottery found here is thick, wheel-made, and well-fired, often coated with a red slip and painted with simple geometric motifs such as horizontal bands and diamonds. The shapes: jars with beaded rims, flanged shoulders, and ring bases, closely resemble those found at Rangpur, a Harappan site in Gujarat. One particularly distinctive find was a hand-made storage jar with incised chevron patterns filled with white pigment, which Vasant Shinde (1985) points out is a decorative technique not commonly seen in Deccan sites.

The settlement pattern at Kaothe suggests deliberate planning. The site is protected by a shallow river meander and lies near wooded hillocks and pastureland, offering a stable ecological setting. Additionally, three smaller satellite sites, Kaothe II, Chhadawel, and Surpan, were identified within a six km radius, likely functioning as related camps or seasonal settlements.

Dhule as Part of the Ancient Rasika

Over the course of history, the region now forming the Dhule district has fallen under the influence of many different political and cultural powers. Little is currently known about its early history; however, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These are better understood when placed in the context of Khandesh and the northwestern Deccan, to which Dhule has long been linked by geography, political influences, and culture.

Interestingly, in early Sanskrit literature, Dhule is believed to have formed part of a region referred to as Rasika. This name appears in sources such as the Ramayan and the works of the 6th-century scholar Varahamihira, where Rasika is described as lying to the south of Vidarbha. While the exact territorial extent of Rasika remains uncertain, it is likely that the term referred to a wider cultural zone that included present-day West Khandesh. In the Ramayan, the southern advance of Sugriva’s search party is said to begin from the hills of Rasika. These references indicate that, even if not politically distinct, the area held cultural and geographical significance in the early historic period.

Over the centuries, northern Maharashtra came under the control of various dynasties that ruled different parts of the Deccan. The region may have formed part of the Mauryan Empire during the 3rd century BCE, when Emperor Ashoka extended his dominion over much of the Deccan. This was followed by the rise of the Satavahanas, who ruled for several centuries and maintained control over northern Maharashtra through a network of local chiefs and feudatories.

Abhiras and the Bhamer Fort

In the period following the decline of Satavahana authority in the 3rd century CE, political control in many parts of the Deccan region came to be exercised by local dynasties, some of whom had previously functioned as subordinate chiefs. Among the earliest of these in Khandesh were the Abhiras, who established a line of rulers over parts of Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Malwa. Their first known ruler, Ishwarsena, is noted to have commenced the Abhira era, which is used in several dated inscriptions found across western India.

The Abhiras are frequently associated in historical and ethnographic literature with the Ahir or Gavli communities, who are traditionally pastoralist in occupation. These communities remain present in considerable numbers in Dhule and surrounding districts. The district Gazetteer (1974) notes the persistence of oral traditions referring to early Gavali Rajas, a designation often linked to Abhira chiefs.

Within Dhule district, the fort of Bhamer, located in Sakri taluka, is among the earliest fortified sites which is linked by tradition to Abhira occupation. The fort is built into a rocky escarpment above the Surat–Burhanpur trade route, a key overland corridor from the western coast to the upper Deccan. The site includes a number of excavated chambers and cave structures, some plain and irregular, others exhibiting more formal layouts with pillared interiors. Interestingly, these are locally known as the houses of the Gavali Raja, and their association with early pastoral rule has been preserved in local oral tradition.

As noted earlier, Gavali Raja is a title traditionally associated with early pastoral rulers, and often, by implication, with the Abhira chiefs. While formal evidence remains limited, such references may point to an early phase of occupation. The fort remained in use over time and was subsequently incorporated into the holdings of later dynasties in the Khandesh region.

Sendrakas and Early Epigraphic Mentions of Pimpalner

Following the decline of the Abhira authority, the Khandesh region came under the control of larger powers, notably the Rashtrakutas and the Chalukyas of Badami. Political consolidation during this period appears to have been effected through a network of feudatories, among whom the Sendrakas are attested in the mid-7th century CE.

Inscriptions describe the Sendrakas as subordinates of the Chalukyas of Badami, with their sphere of influence extending over parts of southern Gujarat and northern Maharashtra. A series of copper-plate grants, noted in the district Gazetteer (1974), point to their presence in the region. Three grants were issued by Allasakti and one by his son Jayasakti.

Interestingly, the earliest of these, dated to the Abhira year 404 (653 CE), records a donation of land in the village of Pippalikheta, which is identified with present-day Pimpalner of the Sakri taluka in the district. The record establishes Allasakti’s authority in this part of Khandesh and offers a rare epigraphic mention of a locality within the present district during this early period.

The Yadavas and Hemadpanthi Mandirs

By the 12th century CE, control over Khandesh passed into the hands of the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, who had by then replaced the Western Chalukyas as the principal power in the region. Their territory extended across much of Maharashtra, and their presence in northern districts is marked by surviving architectural remains.

In Shirud village, located near the southern edge of Dhule district, stands a Mandir dedicated to Kalika Mata, built in the Hemadpanthi style commonly associated with Yadava patronage.

Medieval Period

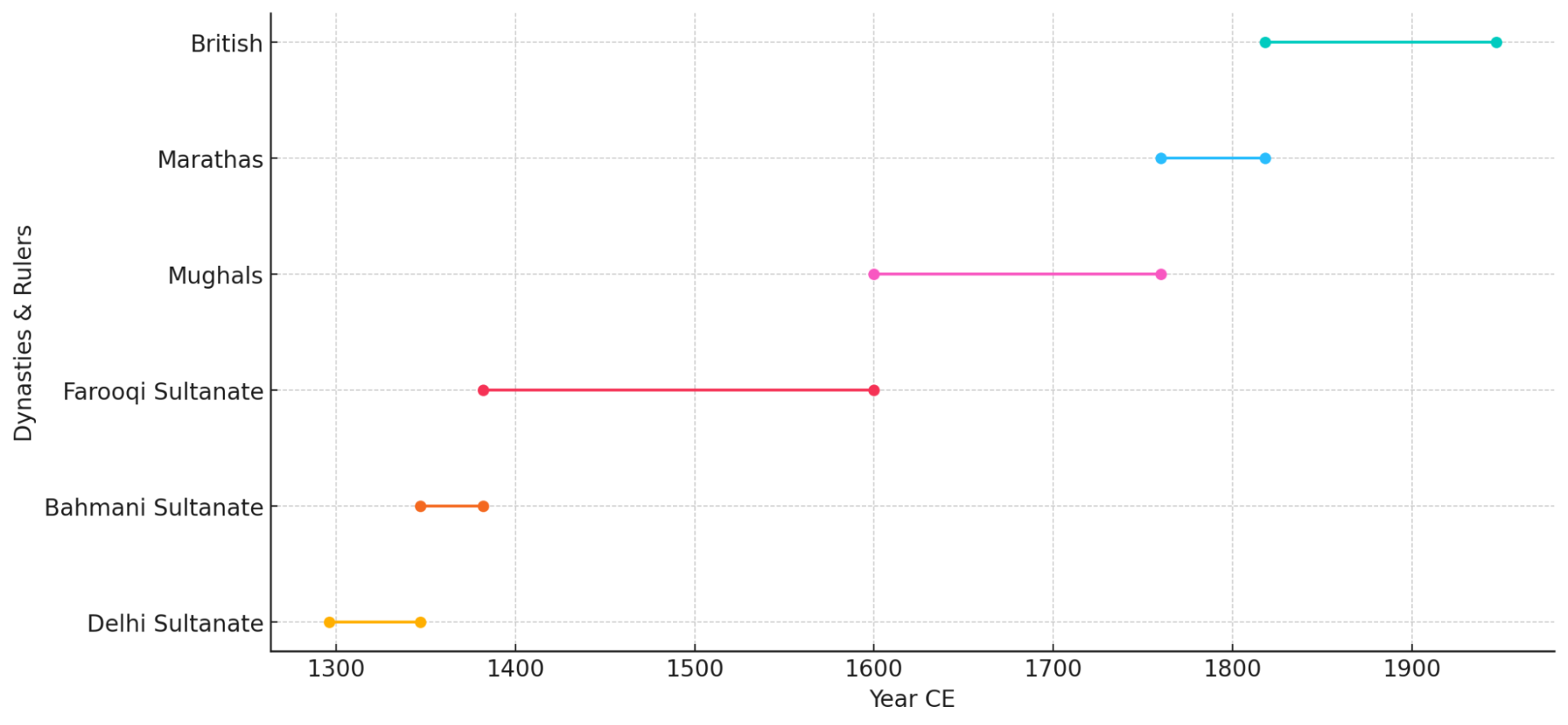

The medieval period in Dhule district, which spans roughly from the late 13th century to the early 17th century, was marked by major political transitions and the rise of a distinct regional power. Over these centuries, the region witnessed the influence of northern forces, the turbulence of Deccan rebellions, and eventually the emergence of a local dynasty, the Farooqi rulers of Khandesh, who made Dhule one of their early centres of power.

Delhi Sultanate

The earliest phase of medieval rule in this region is linked to the southern campaigns of the Delhi Sultanate. By 1318, the Yadava kingdom was annexed, and its territories, including parts of present-day Khandesh, in which Dhule is located, came under the Delhi Sultanate’s control.

During the reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq (1325–1351), the Sultan shifted his capital from Delhi to Devagiri, briefly renaming it Daulatabad in an ambitious attempt to control the Deccan more directly. As part of this administrative push, the area of present-day Dhule came under the oversight of provincial officers based in Ellichpur (now Achalpur in Amravati district), in the Berar region.

However, these efforts were short-lived. The Sultanate struggled to maintain control over its southern territories, and local forces increasingly asserted their independence.

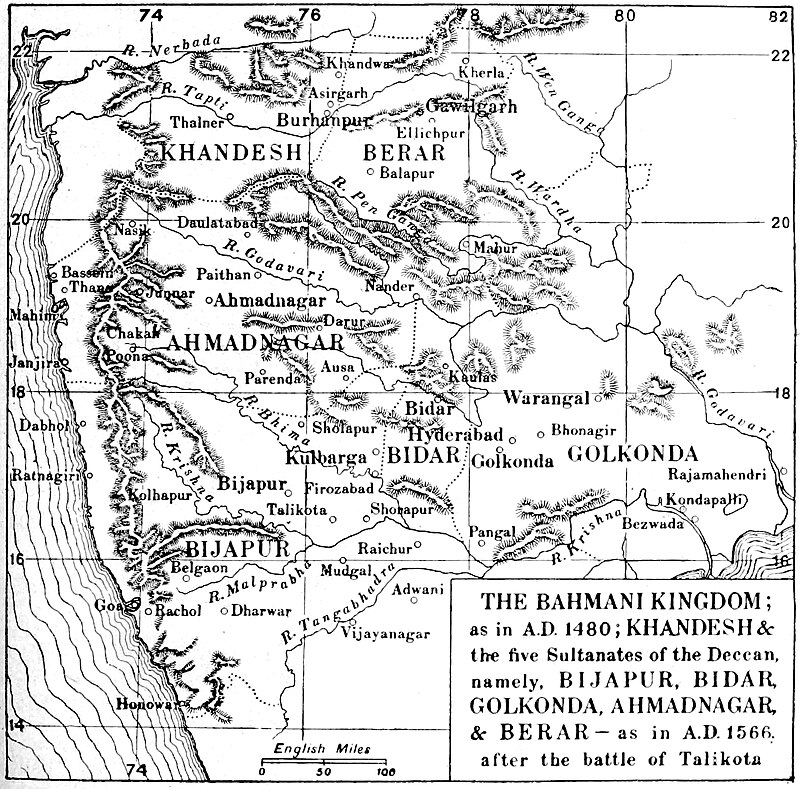

Rise of the Bahmani Sultanate and Establishment of Farooqi Rule in Dhule

By the mid-14th century, the Delhi Sultanate’s grip on the Deccan had weakened considerably. In 1347 CE, Hasan Gangu, a former officer under Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, rebelled and established the Bahmani Sultanate with its capital at Gulbarga (Karnataka).

While much of the Deccan came under Bahmani control during this period, the northern tract of Khandesh, including the present-day Dhule district, remained loosely attached to Delhi. The Sultanate’s administrative presence had weakened, and the Bahmani kingdom had not yet extended its authority into the region.

To reassert some measure of control in the area, Firuz Shah Tughluq, then ruling in Delhi, granted the territories of Thalner and Karanda to a cavalry officer named Malik Raja (also known as Malik Ahmad).

Malik Raja and the Early Farooqi Seat in Thalner

A significant chapter in the history of Dhule unfolded between the late 14th and early 17th centuries, when parts of the present district formed the early seat of the Farooqi dynasty, rulers of the Khandesh Sultanate. The dynasty governed a strategically located tract between the Tapi River and the Satpura ranges, with influence extending into northern Maharashtra and adjacent regions of central India. Their territory lay along important overland trade and military routes connecting Gujarat, Malwa, and the Deccan.

The founder of the dynasty, Malik Raja, also referred to in some sources as Malik Ahmad, rose from relatively modest military service under the Tughluq Sultanate. Malik Raja first appears in records as a horseman in the Tughluq army. During the revolt of the Deccan nobles, he withheld support for the Bahmani cause and later aligned with rebel officers in the region. He is mentioned among the followers of Bahram Khan Mazandarani, the governor of Daulatabad, who had risen in rebellion during the troubled years following Muhammad bin Tughluq’s death. The rebels were defeated and forced to flee westward, after which Malik Raja entered the direct service of Firuz Shah Tughluq, who then ruled in Delhi.

According to Ferishta, Malik Raja’s family claimed descent from Caliph Umar al-Faruq, the second caliph of Islam. His father, Khan Jahan Faruqi, is said to have served as a minister under the Khilji rulers. Malik Raja is believed to have first come to the Sultan’s notice during a royal hunt in Gujarat. His conduct on that occasion earned him a command of 2,000 horses, and he was soon after granted lands that now lie across the present-day Nandurbar and Dhule districts. He established his base at Thalner, a fortified settlement on the banks of the Tapi River in present-day Dhule district.

The Khandesh region at that time, according to later records such as the Ain-i-Akbari, was thinly inhabited and largely unsettled, save for the fort of Asirgad (Madhya Pradesh). The early population consisted of small groups and pastoral communities, among whom the Ahirs are noted as having held local authority.

In 1370, Malik Raja formally marched to assume control of his new charge. That same year, he led a campaign against Bahirji, the Raja of Baglan, who ruled over a hill district to the west. Bahirji was defeated and compelled to send tribute to Delhi, including elephants, pearls, and muslin cloth. On returning to Thalner, Malik Raja prepared a further offering for the Sultan: elephants draped in velvet, camels loaded with local textiles, and other signs of his success. Firuz Shah is said to have remarked that the governor of Gujarat had failed where Malik Raja had succeeded, and in recognition, awarded him the title of Sipah Salar (Commander-in-Chief) of Khandesh and increased his rank to command 3,000 cavalry.

Though he exercised effective control over the territory, Malik Raja did not assume the title of Sultan. He and his successors retained the designation Khan, and from this the term Khandesh, or “land of the Khans,” came into use. The Ain-i-Akbari records that Malik Raja ascended the throne at Thalner in Hijri 784 (1382 CE) under the title Adil Shah, and that he ruled for 17 years. His authority extended eastwards into Gondwana, and he is said to have received tribute from the rulers of the Garha-Mandla Kingdom. His cavalry, according to Ferishta, numbered as many as 12,000, and his reputation reached as far as Vijayanagar in the south.

His military establishment, as recorded by Ferishta, consisted of some 12,000 cavalry, a substantial force for the period, and his standing was such that even the distant court of Vijayanagar maintained friendly correspondence.

The town of Thalner, situated on the banks of the Tapi River, formed the nucleus of Farooqi power in its formative years. Located within the bounds of the present-day Dhule district, it served as the original seat of Malik Raja’s administration. Notably, Abul Fazl, writing in the Ain-i-Akbari, remarks that “Thalner was for a time the capital of the Farooqi princes,” and notes the strength of its fortifications despite its location on open ground. From Thalner, the dynasty gradually extended its control across the wider region of Khandesh. Other forts in the vicinity, most notably at Laling, played important roles as military outposts and administrative centres.

For over two centuries, the Farooqi rulers governed Khandesh from this regional base, and throughout that period, the area now forming Dhule district remained central to their dominion: politically, militarily, and geographically.

Nasir Khan & Burhapur as the New Capital

After Malik Raja’s death in 1399, his elder son Nasir Khan (also called Garib Khan) succeeded him. Initially based at Laling, Nasir moved swiftly to secure the nearby fort of Asirgad, then held by a local ruler, Asa Ahir. The means by which Nasir acquired the fort are described in later sources as deceptive. He requested Asa’s hospitality, citing unrest and asking for protection for his family. Asa agreed, but the arriving party proved to be armed men, who killed Asa and his sons. Nasir then took possession of Asirgad and returned to Laling.

The following year, Nasir founded two towns: Zainabad on the east bank of the Tapi, and Burhanpur on the west. The names are said to honour the family’s spiritual guide, Shaikh Zainuddin Shirazi. Of the two, Burhanpur proved the more enduring and, in time, became the capital of the Farooqi state.

In 1417, with the support of Hoshang Shah of Malwa, Nasir Khan captured Thalner from his brother Malik Iftikar Hasan and imprisoned him. From that point forward, the dynasty’s authority was firmly consolidated in the region.

The Farooqi dynasty continued through successive generations, maintaining its independence through diplomacy and military strength. The line of rulers from Malik Raja to Bahadur Khan extended over two centuries:

- Malik Raja (1382–1399)

- Nasir Khan (1399–1437)

- Miran Adil Khan I (1437–1441)

- Miran Mubarak Khan I (1441–1457)

- Miran Adil Khan II (1457–1501)

- Daud Khan (1501–1508)

- Ghazni Khan (1508)

- Alam Khan (1508–1509)

- Miran Adil Khan III (1509–1520)

- Miran Muhammad Shah I (1520–1537)

- Miran Mubarak Khan II (1537–1566)

- Miran Muhammad Shah II (1566–1576)

- Hasan Khan (1576)

- Raja Ali Khan (1576–1597)

- Bahadur Khan (1597–1601)

The dynasty’s rule came to an end in 1601, when Khandesh was annexed by the Mughal Empire under Emperor Akbar. The region was thereafter integrated into the larger administrative framework of Mughal India.

Tombs of Farooqi Rulers

It is important to note that although Burhanpur became the political centre of the Farooqi state in the later years, the town of Thalner (the dynasty’s original seat) continued to hold much ceremonial and ancestral importance. It was here that several early rulers were buried, and their tombs remain preserved with Arabic inscriptions. Notable interments include Malik Raja (d. 1396), Malik Nasir (1437), Miran Adil Khan (1441), and Miran Mubarak Khan (1457). The continued use of Thalner for royal burials, long after the capital had shifted southward, in many ways, reflects the enduring association of the dynasty with its earliest centre of power.

Mughal Rule in Dhule

In 1601, the Mughal emperor Akbar, then engaged in expanding and consolidating control across the Deccan, annexed Khandesh into the Mughal Empire, and subsequently, the rule of the Farooqi dynasty came to an end. The region was absorbed into the Mughal administrative structure and attached to the Subah of Ahmadnagar, with its strategic centre at Burhanpur.

The earliest references to the region under Mughal dominion include that of Khwaja Abul Hassan, a general in the service of Shah Jahan, who is recorded to have passed the rainy season of 1629 in the vicinity. A subsequent episode of note in Dhule occurred in 1630. It is mentioned in the Khandesh Gazetteer (1880) that during that time, Pimpalner “became the scene of the defeat” of the rebel general Khan Jahan Lodi.

Maratha Expansion and the Role of Balaji Balwant

By the mid-18th century, the Maratha Confederacy had replaced the Mughals as the dominant power across the Deccan. After the defeat of Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I at the Battle of Bhalki in 1752, the Khandesh region, including Dhule, came under Maratha control.

At this time, Dhule town was noted to be little more than a modest settlement, lying between two more prominent administrative centres: Laling and Songir. These areas, known as parganas (revenue units), were placed under the control of the Vinchurkar family, a prominent Maratha house who were aligned with the Peshwa.

However, the town soon suffered disruption. In 1803, amidst military incursions by the Holkars (a Maratha faction based in Malwa) and compounded by a severe famine, Dhule was described to be largely abandoned. The population fled, and local infrastructure deteriorated.

Recovery efforts began the following year. A local administrator named Balaji Balwant, a trusted subordinate of the Vinchurkar family, was tasked with restoring order. He undertook the repair of the local fort, encouraged displaced residents to return, and re-established basic services. In recognition of his efforts, Balaji Balwant was awarded land grants (inam) and entrusted with the administration of the Songir-Laling tract. Over time, he made Dhulia (as the town was then known) his base of operations and continued to govern from there until the arrival of British forces in 1818.

Ahilya Barav and Holkar Influence

During the same period, parts of present-day Dhule district came under the influence of the Holkar dynasty, based in Maheshwar (in present-day Madhya Pradesh). Under the reign of Ahilyabai Holkar (1767–1795), it is said that territories including Laling, Thalner, Songir, Sultanpur, and Galna were within Holkar control.

One of the enduring architectural legacies of this period is found at Ahilyapur, a village situated along a trade and military route connecting Maheshwar to Pune. There, a five-storey stepwell, known locally as the Ahilya Barav, was constructed to support the needs of merchants, troops, and travellers.

Built from brick and stone, the stepwell covers over 1,000 square metres and features 13 arches, with space said to accommodate up to 100 bullocks and mounted troops. Locally known as “12 bailancha mothnad” (area of twelve bullock stalls), the stepwell includes a central reservoir and remnants of a piped water system, which is indicative of its practical and logistical importance. It remains a rare surviving example of multi-use public architecture from the late Maratha period in this region and continues to be maintained and is illuminated annually on the birth anniversary of Ahilyabai Holkar.

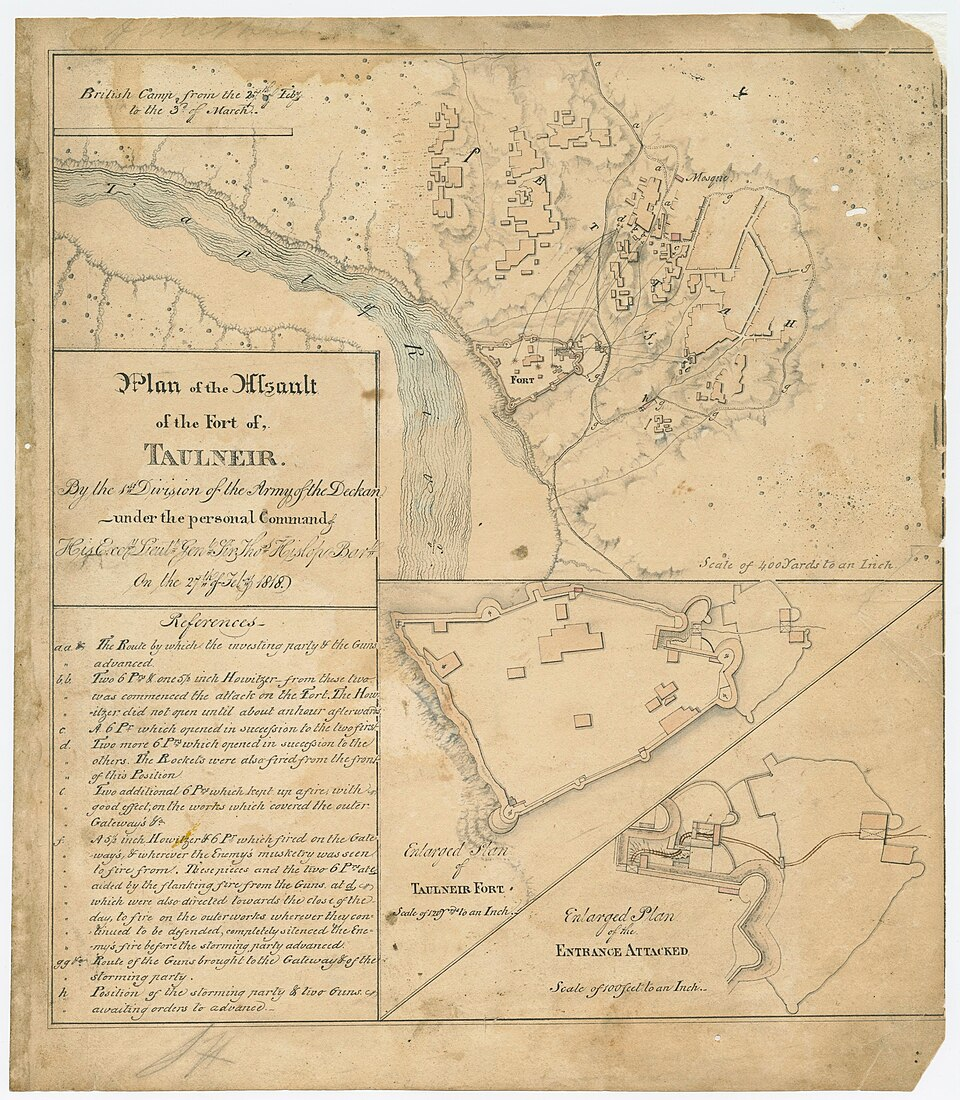

British Conquest and the Fall of Thalner Fort (1818)

By the early 19th century, the balance of power in the region shifted with the advance of British forces during the Third Anglo-Maratha War. In 1818, British military operations culminated in the annexation of Khandesh. Among the early confrontations was the storming of Thalner Fort in the Dhule district. The British capture of Thalner Fort was described in the district Gazetteer (1974) as "one of the bloodiest incidents in the conquest of Khandesh." The assault on the fort was led by General Hislop, and the engagement resulted in the deaths of approximately 250 defenders, while British casualties were reported to be 25.

The British decision to attack was based on intelligence that the fort's western side was poorly defended, lacking artillery. This weakness allowed them to position their guns for a direct assault on the fort’s gates from the northeast angle. The attack that followed was swift but met with determined resistance. Despite being outgunned and encircled, local defenders engaged the British in fierce close combat. The initial breach gave way to hand-to-hand fighting within the fort’s interior. Lieutenant Colonel Valentine Blacker, writing in his memoirs of the Maratha War, recounted that “in a moment, [the enemy] laid them all dead, except Colonel Murray, who, covered with wounds, fell towards the wicket.” Though momentarily held back, British troops regrouped and eventually overran the stronghold.

The aftermath of the battle was marked by a controversial act: the execution of the fort’s commandant. Hanged from a tree near the flagstaff tower, his death was recorded in the district Gazetteer (1974) as a point of local outrage. Subsequent British sources also criticized General Hislop’s decision, with some viewing it as excessive and damaging to relations with the local population.

Although Thalner Fort lost much of its strategic relevance after the British victory, the site retains numerous tombs of those who died in the conflict, serving as enduring markers of this battle and of resistance.

British Annexation and the Development of the Dhulia Town

With Thalner secured and Khandesh annexed following Baji Rao II’s formal surrender in June 1818, the British East India Company moved quickly to establish administrative control. As part of this administrative reordering, the town of Dhule was identified as a suitable centre for governance. Notably, Captain John Briggs, who was appointed as the first Political Agent of Khandesh, selected Dhule to serve as the district headquarters.

To promote settlement and encourage the growth of the new district town, the British introduced a series of incentives. Land was granted rent-free in perpetuity for building purposes, and both returning residents and new settlers were provided assistance in constructing homes. The town was laid out according to a formal grid plan and divided into distinct neighbourhoods. Ganesh Suburb became home to Marwari traders, craftsmen, and artisans, while Briggs’ Suburb housed government officials and featured more substantial stone-built residences.

As the town began to take shape, a central market was established to serve its growing population. While Dhule initially lacked large-scale industry in its early days, the local production of coarse cotton blankets and turbans supported a modest textile economy. This activity later expanded with the introduction of a steam-powered cotton press by the Volkart Brothers of Bombay, signalling the beginning of commercial-scale manufacturing in the region.

These early administrative and infrastructural efforts laid the groundwork for Dhule’s transformation into a functioning district centre under British rule, and in his official correspondence, Captain Briggs described the emerging town as “a quaint settlement, nestled amidst garden farms and bounded by an irrigation canal and a river.”

Colonial Period

Dhule as a District Headquarters

Following the British annexation of Khandesh in 1818, as mentioned above, the settlement of Dhule was selected as the headquarters of the newly created Khandesh district. At its inception, the district comprised the present-day territories of Dhule and Jalgaon, along with the talukas of Malegaon, Nandgaon, and Baglan. The latter three were transferred in 1869 to the then newly formed Nashik district, in accordance with administrative reorganisation undertaken by the Government of Bombay.

Further changes were introduced in 1906, when the original Khandesh district was bifurcated into two separate units: East Khandesh, with its headquarters at Jalgaon, and West Khandesh, administered from Dhule. The new West Khandesh district included the talukas of Dhule, Nandurbar, Navapur Peta, Pimpalner, Shahada, Shirpur, Sindkheda, and Taloda. This division had the effect of consolidating Dhule’s role as an administrative centre for the western portion of the Khandesh region.

Trade and Agricultural Economy

By the latter half of the 19th century, Dhule had developed a modest market economy. The town was known for its trade in agricultural produce, particularly cotton and linseed. Cotton was brought in from villages situated in the Satpura range to the north and north-west, where its cultivation formed part of the seasonal crop rotation practiced in those upland areas. It was typically processed into coarse cloth, woollen garments, and turbans, either for local use or for redistribution through intermediate markets. Cotton continues to be cultivated in the Satpura tracts of Dhule district, maintaining a pattern of agricultural activity that dates from this earlier period.

The Flood of 1872

In the month of September 1872, the district of Dhule experienced a flood of considerable magnitude. According to the Khandesh Gazetteer (1880), the precipitation commenced on Friday, the 13th of September, and continued without interruption until the afternoon of Sunday the 15th. During this period, the Panjhra River, which rises in the uplands of Sakri taluka near present-day Pimpalner and flows westward as a tributary of the Tapi, exceeded its ordinary bounds.

The resulting inundation affected not only Dhule town but also numerous villages along the river’s course. The floodwaters were noted to have breached the banks with such force as to carry away public roads and render major communication routes impassable. Telegraph lines were disrupted, effectively isolating the district from the outside. It was reported that no fewer than 500 dwellings were destroyed, and the damage to property, both public and private, was extensive.

The estimated value of the loss was placed at £160,000 (Rs 16,00,000 in contemporary valuation), a figure indicating not merely physical destruction but the disruption of agrarian routines upon which much of the local economy depended. Among those most severely affected were indigenous communities, including the Bhils, many of whom were rendered destitute.

In the immediate aftermath, private charity played a principal role in providing relief, followed in part by allocations from the Khandesh rice fund. A public meeting held in Dhule led to the establishment of a local relief committee, under whose direction the initial phase of assistance was organised. The event remains among the more serious natural calamities recorded in the district’s recent history.

Railway Extension and Communication

In 1900, a branch railway line was opened connecting Chalisgaon to Dhulia (as it was then spelled), thereby linking the district more directly to the Bombay–Bhusawal trunk line. The branch extended approximately 27.4 km into the Dhule district and was constructed with a broad gauge of 5 ft. 6 inches. The railway facilitated the transport of agricultural produce, particularly raw cotton, and served as a logistical conduit for local traders and officials.

The line included intermediate stations at Jamda (14.5 km from Chalisgaon) and Rajmane (24 km from Chalisgaon), which provided access for the surrounding countryside. Originally operated by steam locomotives, the branch was later electrified in accordance with general upgrades to the Indian railway system. The line continues to serve local freight and passenger traffic.

Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade & the Sanshodhan Mandal

During the early decades of the 20th century, Dhule became the residence of Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade (1863–1926), a historian of repute whose principal interest lay in the study of Maratha history. It is said that Rajwade settled in Dhule following a disagreement with officials at the Indian History Research Board in Pune. He remained in the town for nearly 26 years, during which time he devoted himself to the collection and preservation of historical material.

Rajwade’s personal archive comprised manuscripts, inscriptions, and documents in a variety of languages, including Sanskrit, Farsi, Modi, Marathi, and Hindi. After his death, his followers established the Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade Sanshodhan Mandal on 9 January 1927. Originally known as the Itihasacharya Research Board, the institution was founded to house and extend Rajwade’s collection. It now serves as a research centre, maintaining over 20,000 texts and a membership of more than 750 scholars and readers.

The Mandal continues to function as a repository of primary sources for historical research pertaining to Maharashtra and neighbouring regions.

Post-Independence Period

Following the independence of India in 1947, the territory comprising the present-day Dhule district was placed under the jurisdiction of Bombay State. The region, previously considered part of the wider Khandesh tract, continued under existing administrative arrangements until the linguistic reorganization of states in 1960, when Bombay State was divided. Thereafter, Dhule was incorporated into the newly formed State of Maharashtra and was designated a separate district.

For several decades thereafter, Dhule district comprised nine talukas, which are Dhule, Sakri, Shirpur, Sindkheda, Akkalkuwa, Akrani, Shahada, Taloda, and Nandurbar. This structure remained in place until 1 July 1998, when the district was bifurcated and the five western talukas, namely, Akkalkuwa, Akrani, Shahada, Taloda, and Nandurbar, were carved out to form the new district of Nandurbar.

Following this division, Dhule district came to consist of four talukas: Dhule, Sakri, Shirpur, and Sindkheda (also spelled Shindkheda). Currently, these are grouped into two administrative subdivisions: the Dhule subdivision, comprising Dhule and Sakri talukas, and the Shirpur subdivision, comprising Shirpur and Sindkheda.

Sources

A Ghosh ed. 1993. “Indian Archeology 1854-55: A Review”. Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.

Arvind M. Deshpande. 1987. John Briggs in Maharashtra: A Study of District Administration Under Early British Rule. Mittal Publications, India.

G. Jouveau-Dubreuil. 1920. Ancient History of the Deccan. Central Secretariat Library, Pondicherry.https://www.indianculture.gov.in/rarebooks/a…

Government of Bombay. 1896. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Volume I, Part II: History of the Konkan Dakhan and Southern Maratha Country. Government Central Press, Mumbai.

Government of Maharashtra. 1974. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Dhulia District. Gazetteers Department, Mumbai.

H.S Thosar. 1990. "The Abhiras in Indian History." Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol 51, Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44148188

Ishwari Khandelwal. 2018. The Tombs of Farukki Ruler at Thalner - A Forgotten Heritage. Studio Adda Blog.https://studioaddablog.wordpress.com/2018/11…

Jadunath Sarkar. 1949. Ain-I-Akbari of Abul Fazl-I-Allami, Vol. 2 Ed. 2nd. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Kolkata.

James M Campbell. 1880. Gazetteer Of Bombay Presidency: Khandesh. Vol.12. Government Central Press, Bombay.

M.S. Rao. 1987. Social Movements and Social Transformation: A Study of Two Backward Classes Movements in India. Manohar Publications.

R. V. Joshi and A. R. Marathe. 1974. "Stone Age Sediments from the Kan River (Tapti Basin), Dhulia District—A Sedimentological Study." Vol. 34, No. ¼, Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute.https://www.jstor.org/stable/42930128?seq=1

Radhey Shyam. 1981. The Kingdom of Khandesh, Idarah-i-Adabiyat-i-Delli. Delhi.

Suresh Nimabalkar. Bhamergad. Durgbharari.https://durgbharari.in/bhamergad/#google_vig…

Thomas Wolseley Haig. 1907. Historic Landmarks of the Deccan. Pioneer Press, Allahabad.https://archive.org/details/historiclandmar0…

Vasant Shinde. 1985. “Kaothe – A Late Harappan Settlement in the Central Tapi Basin.” Vol. 44, Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/42931017.pdf

Wikipedia: Dhule District

Wikipedia: Mahur, Dhule District Website.

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.