HINGOLI

Language

Last updated on 21 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Hingoli is a district located in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra. It is home to multiple speech communities (a group of people who use and understand the same language or dialect), each maintaining its distinct linguistic traditions. While Marathi serves as the predominant language throughout the district, Urdu, Hindi and Banjari function as other significant languages of communication. The district’s linguistic landscape also includes lesser-known varieties such as Kolhati.

Linguistic Landscape of the District

According to the 2011 Census of India, Hingoli district had a total population of approximately 11.77 lakh (11,77,345). Of this population, 83.53% reported Marathi as their first language. This was followed by Urdu (6.86%), Hindi (4.82%), and Banjari (3.23%). Other languages spoken as mother tongues included Telugu (0.43%), Marwari (0.41%), Vadari/Wadari (0.24%), Paradhi (0.12%), Gujarati (0.11%), Kashmiri (0.05%), and Rajasthani (0.03%).

Language Varieties in the District

Variation of Marathi in Hingoli

Marathi is the main language spoken in Hingoli district. As per the 2011 Census, around 9,83,442 people, or 83.53 percent of the population, speak Marathi as their mother tongue. It’s used widely across daily life, in homes, markets, schools, and public spaces. But even within this shared language, there are local differences in how it's spoken, especially between urban and rural areas.

Locals in Hingoli often note that Marathi spoken in rural areas has its own character. The words, pronunciation, and the way people form expressions often differ from how they’re used in urban areas. These differences reflect the region's unique cultural identity and everyday usage.

Locals describe how certain common words in rural Hingoli differ from what is used elsewhere in Maharashtra. These words are familiar within the region but might sound unusual to outsiders.

|

Marathi |

Hingoli Marathi |

English Meaning |

|

Gudagha (गुडघा) |

Tongala (टोङ्गाळा) |

Knee |

|

Manus (माणूस) |

Bua (बूआ) |

Man |

|

Majha (माझं) |

Mapla (मापळा) |

Mine |

|

Tujha (तुझं) |

Tupla (तुपळा) |

Yours |

Locals also note that certain phrases in rural Hingoli Marathi differ not just in vocabulary, but also in tone and structure. This is especially noticeable in rhetorical or emotionally expressive speech.

|

Marathi |

Hingoli Marathi |

English Meaning |

|

Apan shatru aahot ka? (आपण शत्रू आहोत का?) |

Apala kay dhuryala-dhura hay ka? (आपला काय धुर्याला-धुरा हाय का?) |

Are we enemies? |

The meaning is the same, but the Hingoli version carries a more colorful, locally rooted expression. Phrases like these are commonly used in casual, everyday conversation, often with a mix of humor or intensity, depending on the context and relationship between the speakers.

Banjari

Banjari, also known as Lambani, Lambadi, Gormati, or Lamani, is a language spoken by a large community spread across various regions of India. It is spoken by the Banjara or Laman community, originally from the Mewar region of Rajasthan. Over time, this community migrated to various parts of India in search of trade and employment, leading to a wide geographical spread. Today, its speakers can be found in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal, with smaller populations in other states. Very notably, the Banjari-speaking community is the fourth largest linguistic group in Hingoli district, with 3.23% of the population reporting it as their mother tongue as per the 2011 Census.

Banjari does not have a native script (original writing system), which has shaped how the language is used and preserved. Instead of writing in their own script, speakers have adapted the writing systems of surrounding regional languages. In Maharashtra, for example, they use the Devanagari script (used for Marathi and Hindi), while in Karnataka, the Kannada script is used.

Banjari has 6 vowels:

a, e, i, o, u (and longer versions like ā, ī, etc.)

Long vowels are usually not used at the end of words.

There are 32 consonants, many like those in Marathi.

But some sounds, like the Marathi "थ" (/th/ with a breath), do not exist in Banjari.

Also, Banjari uses nasal sounds (like "n" in "song"), but changing them doesn’t usually change the word’s meaning. Aspirated sounds (with a breathy sound) appear mostly at the start of words.

Banjari shows a fascinating blend of its own vocabulary and forms borrowed from languages like Marathi and Hindi. This blending is most noticeable in everyday words, terms for family, the body, colours, food, and numbers. Many of these look and sound quite similar across all three languages, showing how close contact and migration have shaped the language.

In terms of kinship and pronouns, Banjari uses words that are nearly identical to Marathi and Hindi. For instance, sāsu means ‘mother-in-law’ in all three. The word for father in Banjari, bā, is closely related to bābā or vadil in Marathi and pitāji in Hindi. Even the second-person singular pronoun tu is the same across the three languages.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

sāsu |

sāsu |

sās |

mother-in-law |

|

bā |

bābā / vadil |

pitāji |

father |

|

dhani |

dhani / navarā |

pati |

husband |

|

tu |

tu |

tum |

you |

Words for body parts follow a similar pattern. In many cases, there is almost no difference in form, for example, dāt for ‘tooth’, hāt for ‘hand’, and gāl for ‘cheek’ are the same in Banjari and Marathi, and very close in Hindi too. This suggests a strong set of shared roots or long-term borrowing between the languages.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

hot |

oth |

hoth |

lips |

|

dāt |

dāt |

dānt |

tooth |

|

hāt |

hāt |

hānth |

hand |

|

gāl |

gāl |

gāl |

cheek |

|

anguthā |

angathā |

anguthā |

thumb |

|

pet |

Pot |

pet |

stomach |

|

kapāɭo |

kapāɭ |

sir |

forehead |

|

ṭāng |

Pāy |

ṭāng |

leg |

The same goes for colours. Banjari’s haro (green) and niɭo (blue) are very close to hirwā and niɭā in Marathi and harā, nilā in Hindi. The small vowel differences at the end don’t change the meaning, but they do reflect local phonological patterns.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

haro |

hirwā |

harā |

green |

|

niɭo |

niɭā |

nilā |

blue |

Food vocabulary is especially rich in borrowed or shared forms. Words like kāndo (onion), seb (apple), and santra (orange) are consistent across the three languages. A few items, like angur (grapes), also show influence from Marathi, which uses jāmbhuɭ, reflecting regional variety even within a shared root.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

kāndo |

kāndā |

pyāj |

onion |

|

muɭo |

muɭā |

muɭi |

radish |

|

angur |

jāmbhuɭ |

angur |

grapes |

|

santra |

santra |

santra |

orange |

|

seb |

sapharchandǝ |

seb |

apple |

|

āṭo |

pith |

āṭā |

flour |

|

nimbu |

limbu |

nimbu |

lemon |

|

ālu |

baṭāṭā |

ālu |

potato |

|

bhindā |

bhendi |

bhindi |

lady finger |

In numbers too, Banjari keeps very close to both Marathi and Hindi, particularly for the basic counting numbers. Words like ek (one), ʧār (four), and sāt (seven) are essentially the same. For numbers above twenty, Banjari uses a compounding system—wisan ek for twenty-one, wisan di for twenty-two, and so on.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

ek |

ek |

ek |

one |

|

ʧār |

ʧār |

ʧār |

four |

|

nav |

nau |

nau |

nine |

|

sāt |

sāt |

sāt |

seven |

|

das |

dahā |

das |

ten |

|

sǝu |

shambhar |

sǝu |

hundred |

|

vis |

vis |

bis |

twenty |

Ordinal numbers are also easy to form. In Banjari, adding -ne to a cardinal number makes it ordinal. For instance, ekne is ‘first’, dine is ‘second’, and tinne is ‘third’. General vocabulary also reflects a strong Marathi and Hindi influence, with many everyday nouns being identical or nearly so.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

phul |

phul |

phul |

flower |

|

pankhā |

pankhā |

pankhā |

fan |

|

pāɳi |

pāɳi |

pāni |

water |

|

ābhaɭ / ābhaɭo |

ābhaɭ |

ākāsh |

sky |

|

mor |

mor |

mor |

peacock |

|

ghodā |

ghodā |

ghodā |

horse |

|

somwār |

somwār |

somwār |

Monday |

|

rāt |

rātrǝ |

rāt |

night |

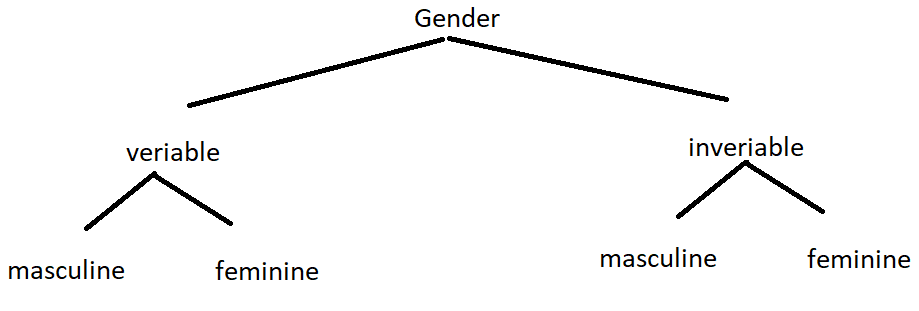

Banjari nouns follow a pattern that shows gender (male or female), number (singular or plural), and case (how the noun functions in the sentence, like subject or object). There is no third gender category (neuter), which is different from many other regional languages.

In Banjari, the general form of a noun is:

Noun stem + gender + number + case suffix

(case suffix = small ending added to show the noun's role in a sentence)

Some nouns use the same root but change the ending vowel to show gender. For example:

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Meaning in English |

|

ghodā |

ghodi |

horse |

|

betā |

beti |

boy/girl |

In Banjari, plural forms (more than one) are often shown through the verb or number word in the sentence, rather than changing the noun itself. This is especially true when the noun is the subject. In such cases, the noun form stays the same, and the listener understands it’s plural based on context.

In other cases, Banjari uses three ways to show plurals:

- Adding a suffix (a small word-ending)

- Repeating the noun (called reduplication)

- Removing part of the original word

|

Singular |

Plural |

Method Used |

Gloss |

|

betā |

betābetā |

Reduplication |

boy → boys |

|

sāsu |

sāsuo |

Adds suffix ‘-o’ |

aunt → aunts |

|

telǝwālo |

telǝwāl |

Ending removed |

oilman → oilmen |

Banjari also uses common endings from other languages to form agent words (called agentive suffixes). For example, wala (male) and wali (female) are added to describe someone doing a job or activity—like telwala = “oil seller.”

Pronouns (words like I, you, they) in Banjaridon’t show gender, but they do show singular/plural. The basic structure is:

Pronoun stem + case suffix

|

Singular |

Plural |

Meaning in English |

|

ma |

ham |

I – we |

|

tu |

tam |

you – you all |

Banjari also uses ekmek for “each other,” just like in Marathi. This shows how closely the two languages are related in structure.

Verbs in Banjari change depending on who is doing the action and when it happens. This process is called conjugation (changing a verb to show tense, number, or gender). For example, jo means “to go,” but its form will change depending on the speaker or time.

|

Base Verb |

Present Tense (3rd person) |

Explanation |

|

jo |

jāwa |

“he/she goes” – adds ‘w’ |

|

baga |

bagawa |

“throws” – adds ‘w’ |

|

lu |

luwa |

“wipes” – adds ‘w’ |

In the past tense, Banjari uses -y after verbs that end in a, u, or o:

|

Verb |

Past Tense |

Meaning |

|

ā |

āy, āyo |

came |

|

so |

soy, soyo |

slept |

|

cu |

cuy, cuyo |

leaked |

There are few compound verbs in Banjari such as:

|

Normal verb |

Compound verb |

Meaning in English |

|

Jo (to go) |

pad jo wad jo so jo dhās jo le jo |

To fall down To fly away To fall asleep To run away To take away |

|

lā (to take/ to accept) |

Ker lā rām lā |

To do To play |

|

dā (to give) |

bhānd da |

To tie |

Kolhati

The Kolhati language is spoken by the Kolhati community, a group historically associated with performance arts such as acting, dancing, singing, and gymnastics. Their language, like their traditions, has evolved through generations, reflecting both their unique cultural identity and social history.

There is a very interesting legend which is tied to the origins of this community. According to this story, when Bhagwan Shiv narrated the origins of mankind to Devi Parvati, he described eighty-four different yonis (species) on Earth, with humans being one of them. Curious about the origins of different castes, Parvati inquired further, to which Shiva explained that every caste descended from a rishi. One particular verse, “Kumbhak Rushi prasidha jagati, Kolhati garbhaj,” (transliterated as ‘Kumbhak Rishi is renowned in the world; the Kolhati community is born from him) he says suggests that Kumbhak Rishi is regarded as the progenitor of the Kolhati community. This legend is one of the reasons why many perceive the Kolhatis to be an ancient community. This perception, in many ways, adds to the richness and history of their linguistic traditions.

The Kolhati community is spread across various regions of Maharashtra. According to Arun Gajanan Musle in Languages of Maharashtra (2017), Kolhati speakers can be found in many districts of Maharashtra including Hingoli, in areas such as Vasmat, Kalamnuri, Aundha Nagnath, and Varanga.

Every language evolves uniquely, influenced by its speakers’ history, environment, and social interactions. The Kolhati language, like many others, has a vocabulary enriched by indigenous words as well as borrowings from surrounding languages.

Kinship terms, or words used to describe family relationships, vary widely across languages and cultures. In Kolhati, these terms carry distinct phonetic features and reflect cultural nuances in how family relationships are expressed.

|

Kolhati |

English Transliteration |

Phonetic Transcription |

English Meaning |

|

फप्फी |

Phaphphi |

/pʰəppʰi:/ |

Aunt |

|

माव |

Mav |

/mav/ |

Mother |

|

बप |

baeep |

/bɘp/ |

Father |

They demonstrate the phonetic distinctiveness of Kolhati, particularly through aspirated consonants like /pʰ/ and vowel variations, which shape the rhythm and articulation of the language.

The way seasons are named in Kolhati offers insight into the community’s deep-rooted connection with nature.These seasonal terms, while distinct, exhibit similarities to those in Marathi and Hindi. This suggests a process linguists refer to as ‘borrowing’, which occurs when one language adopts words or structures from another.

|

Kolhati |

English Transliteration |

Phonetic Transcription |

English Meaning |

|

घम |

Gham |

/gʰəm/ |

Summer |

|

पाणी के दिन |

Paani ke Din |

/paɳiː ke di̪n/ |

Monsoon |

|

थंड |

Thand |

/tʰɘ̃d/ |

Winter |

The phrase “पाणी के दिन” (Paani ke Din) literally translates to “Days of Water,” capturing the essence of the monsoon season in a way that is unique to Kolhati culture. This construction is likely influenced by Hindi, yet it reflects how Kolhati speakers conceptualize and express their environmental cycles. Such expressions, in many ways, show how language carries cultural meaning, shaping the way a community experiences and articulates its world.

Sources

Arun Gajanan Musle. 2017. Kolhati. In G.N. Devy and Arun Jakhade (eds.). The Languages of Maharashtra, People’s Linguistic Survey of India Vol. 17, part 2. Orient Blackswan: Hyderabad.

Census of India. 2011.Language Atlas of India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.https://language.census.gov.in/showAtlas

Jayashree Patil. 2014.Study of the Phonology of Lamani Language Spoken in Pune(Master's thesis).Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, Pune.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011.Census of India 2011: Language Census. Government of India.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

R.L. Trail. 1968.Lamani: Phonology, Grammar and Lexicon(Doctoral dissertation). University of Poona.https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/9360

Last updated on 21 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.