Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Connections with the Mahabharat

- Early Dynasties & Political Powers

- Yadava Rule and the Aundha Nagnath Mandir

- Sant Namdev

- Medieval Period

- The Bahmani Sultanate and the Administrative Division of Berar

- Sant Namdev and the Bhakti Movement

- Mughal Conquest and the Formation of the Hyderabad State

- Maratha Ascendancy and the Battle of Kharda (1795)

- Restoration of Aundha Nagnath Mandir under Ahilyabai Holkar

- Shifting Alliances and the Rise of British Influence

- The Nizams of Hyderabad Under the British Paramountcy

- Hingoli under Nizam-British Administration

- Reorganisation of the Hyderabad Contingent

- Mohalla Paltan

- Policing and “Thuggee” Suppression

- Administrative Transfer and The 1853 Treaty

- Rise of Cotton Industry

- Land Revenue

- Education and Social Infrastructure

- Post Independence Era

- Creation of the Hingoli District

- Sources

HINGOLI

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Hingoli district, located in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra has a rich and layered history. It is believed to have once formed part of the ancient Vidarbha kingdom and has long been a site of religious and cultural importance. The Aundha Nagnath Mandir, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiva, is a prominent monument in the district, with its current structure often attributed to the Yadava period.

Under British rule, Hingoli served as a strategic military base for the Nizam of Hyderabad, owing to its location near the administrative frontier. Several areas within the town—such as Mohalla Paltan, Tofkhana, Pensionpura, and Sadar Bazar—bear names linked to this period. Initially part of Parbhani district, Hingoli was established as an independent district on 24 April 1999, becoming one of the administrative units within the Aurangabad Division.

Etymology

The roots of the name Hingoli stretched far into the medieval period. In those days, it is said that the area was known as Wingully. Over time, as languages evolved and cultures merged, Wingully underwent a transformation of its own. It transformed into Wingamulh, and then morphed into Lingoli. It’s not clear what the term meant. The year 1866 proved to be a significant turning point in the journey of this region. It was during this year that the refined and modern name, 'Hingoli,' came into being.

Ancient Period

Connections with the Mahabharat

One of the earliest accounts connected to Hingoli’s local history is drawn from the Mahabharat. According to oral tradition, the Aundha Nagnath Mandir, located in Kalamnuri taluka, was originally built by Yudhishthir, the eldest of the Pandavas, during their exile from Hastinapur. The story holds that during their time in the forest, Yudhishthir established a Mandir dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv at this location.

It is mentioned in one of the articles of Marathwada Tourism website that the mandir which was built by Yudhishthir was an impressive seven-storey structure. However, it was later demolished, and the current building was constructed in the 13th century by the Seuna (Yadava) dynasty.

Early Dynasties & Political Powers

The early history of Hingoli district remains difficult to reconstruct due to the absence of sustained epigraphic or archaeological evidence. However, its location within the broader region of Marathwada allows for certain historical inferences, especially when considered alongside developments in nearby districts such as Parbhani. Until 1999, Hingoli was part of Parbhani district, and the early history of the region is best understood through the shared political and cultural frameworks of the wider Deccan.

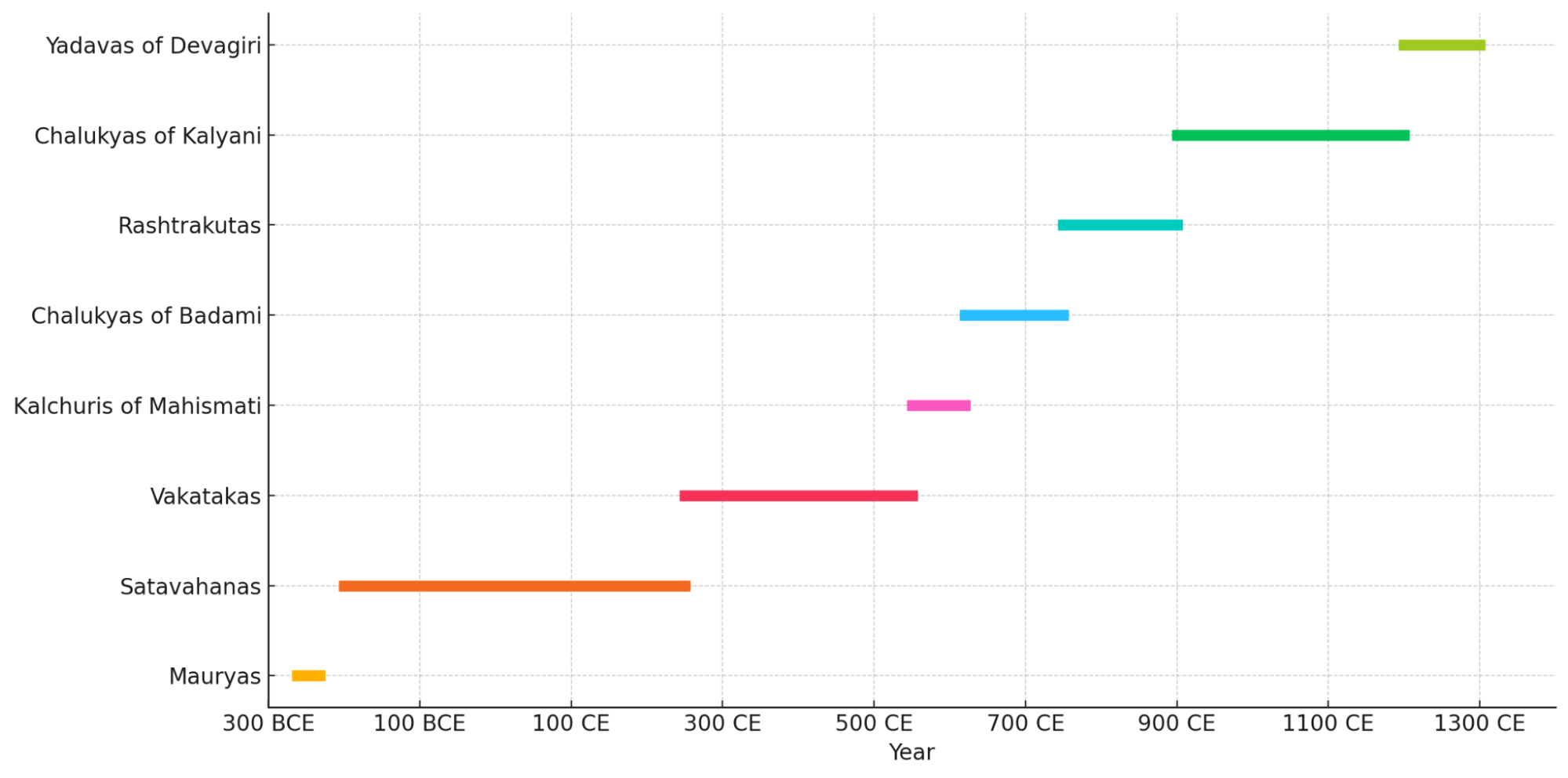

During the 3rd century BCE, much of the Deccan region, including areas surrounding Hingoli, is believed to have been incorporated into the Mauryan administrative system. In the 3rd Century BCE, among the many dynasties that held sway over the Deccan region, such as the Mauryas under the reign of Emperor Ashoka. Inscriptions from the period suggest that the region could have been a part of the Mauryan Empire. Among them, Ashoka’s fifth and thirteenth rock edicts mention communities such as the Rashtrika Petenikas and Bhoj Petenikas, which is especially important. Scholarly interpretations suggest these groups were located in Pratisthana (present-day Paithan, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar) and Vidarbha, respectively. Given Hingoli’s geographical proximity to Sambhaji Nagar, it is plausible that the region came under indirect Mauryan influence or was ruled over by local chieftains from the above-mentioned communities.

Following the decline of the Mauryas around 185 BCE, the Satavahana dynasty emerged as the dominant power in the Deccan. With their capital at Paithan (Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar), the Satavahanas maintained political control across much of central Maharashtra from the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE. The dynasty’s reach and influence likely extended into the region, particularly given its close administrative links with neighbouring Sambhaji Nagar.

Around the mid-3rd century CE, the Vakataka dynasty succeeded the Satavahanas as the principal political power in the eastern Deccan. A branch of the Vakatakas ruled from Vatsagulma, generally identified with modern-day Washim. Since Washim shares a boundary with Hingoli, it is likely that the region fell within the zone of Vakataka cultural or administrative influence, especially during the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

Following the decline of the Vakatakas around 490 CE, political control of much of the region where Hingoli lies, as noted in the Parbhani district Gazetteer (1967) passed to several successor dynasties. These included the Kalachuris of Mahishmati, the Rashtrakutas, and the Chalukyas. While direct evidence of their presence in Hingoli district is lacking, these dynasties held sway over large parts of Vidarbha and may have exercised some degree of control over the area during this period.

Yadava Rule and the Aundha Nagnath Mandir

By the 12th century CE, the Seuna (Yadava) dynasty of Devagiri had established dominance over much of the northern Deccan, including parts of Vidarbha. Their presence or rather influence in Hingoli district is most evident in the construction of the Aundha Nagnath Mandir in Kalamnuri taluka (mentioned above). The current structure, dating to the 13th century, is a notable example of the Hemadpanthi architectural style which is characterised by its use of black basalt and finely carved stonework. The Mandir is dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv in his Jyotirling form and remains an important religious site in the region.

The Yadava dynasty’s rule ended in 1316 CE, following the conquest of Devagiri by Alauddin Khilji of the Delhi Sultanate. This marked the beginning of a new political phase in the Deccan and a shift in control over the wider Vidarbha region, including Hingoli.

Sant Namdev

Sant Namdev made a significant contribution to India's Bhakti movement by spreading the Warkari tradition of Maharashtra far into North India. He was born as Namdev Damasheti Relekar in 1270 in the village of Narsi (now Narsi Namdev) in the Hingoli district of Maharashtra.

Under the guidance of his Guru, Visoba Khechara, he transcended idol worship to realise the omnipresent, formless God. While his early life was spent in Pandharpur, his primary karmabhoomi became the entire Indian subcontinent.

He travelled extensively, most notably to Punjab, where he spent two decades in the village of Ghuman. His message of monotheistic devotion and his rejection of caste distinctions and ritualism resonated so deeply that 61 of his devotional abhangs were included in the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy scripture of Sikhism. He is one of the most revered saints who successfully bridged the spiritual traditions of Maharashtra and Punjab.

Medieval Period

As in the ancient period, the medieval history of Hingoli district is not well documented through local inscriptions or material remains. In the absence of sustained district-level sources, the broader historical developments of the Deccan provide a useful framework for understanding political changes in the region.

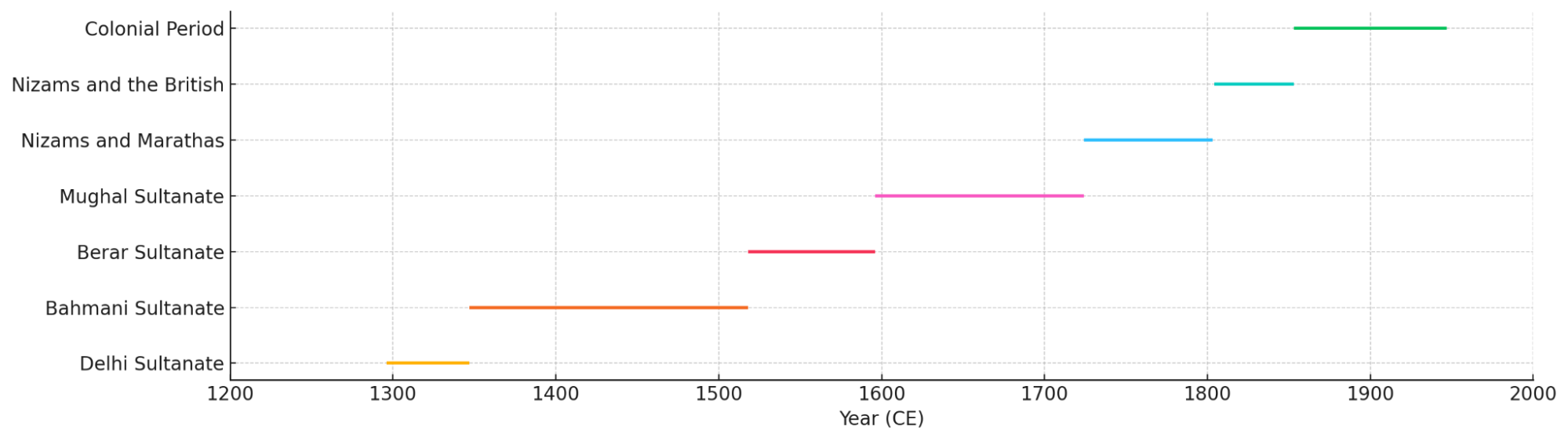

As mentioned above, the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri maintained control over the Deccan into the late 13th century. However, this came to an end with the expansion of the Delhi Sultanate. In 1294, Alauddin Khilji led a campaign into the Deccan, defeating the Yadavas and capturing Devagiri (see Chattrapati Sambhaji Nagar for more). The Parbhani district Gazetteer (1967) notes that further expeditions followed in 1306, 1308, and 1310. These campaigns eventually resulted in the collapse of Yadava authority by 1310–11. Although Hingoli is not yet known to have been mentioned by name in sources from this period, it was under Yadava control and likely passed to the Sultanate as part of the territorial gains in the wider Marathwada region.

The Bahmani Sultanate and the Administrative Division of Berar

In 1347, the Bahmani Sultanate emerged as an independent political entity in the Deccan following its separation from the Delhi Sultanate. The Bahmanis introduced a structured administrative system, dividing their territory into provinces. By 1480, the Deccan was formally divided into eight provinces under Sultan Muhammad Shah III: Bidar, Gulbarga, Bijapur, Berar, Aurangabad, Daulatabad, Khandesh, and Telangana. Hingoli, based on its location, is understood to have formed part of the Berar province.

The Bahmani Sultanate eventually fragmented into five successor states: the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, the Bijapur Sultanate, the Golconda Sultanate, the Barid Shahi dynasty of Bidar, and the Imad Shahi dynasty of Berar. The Berar region, within which Hingoli was situated, became a point of conflict among these Deccan Sultanates.

Sant Namdev and the Bhakti Movement

During the 14th century, Hingoli district became associated with the early Bhakti movement. Sri Sant Namdev (1270–1350), a Vaishnava poet-saint, is traditionally believed to have been born in Narsi village, now in Hingoli district.

A central figure in the Varkari tradition, Namdev composed devotional hymns that are included in the Guru Granth Sahib. His presence in the region represents one of the few directly attested personal histories linked to Hingoli during this time.

Mughal Conquest and the Formation of the Hyderabad State

By the end of the 16th century, the Mughals extended their authority into the Deccan. In 1596, Chand Bibi, acting as regent of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, ceded the province of Berar to the Mughal Empire (refer to Ahilyanagar for more). This administrative transfer included the territory of present-day Hingoli. The Mughals subsequently integrated Berar into their provincial system, with Hingoli remaining within its bounds.

In the early 18th century, Mughal authority in the Deccan weakened significantly. Asaf Jah I, appointed as governor of the Deccan by the Mughal emperor, asserted his independence and founded the Hyderabad State in 1724. Hingoli, as part of the former Berar province, was incorporated into this new political entity. Though nominally independent, the Nizam’s administration operated within a broader context of Mughal decline and emerging regional powers.

Maratha Ascendancy and the Battle of Kharda (1795)

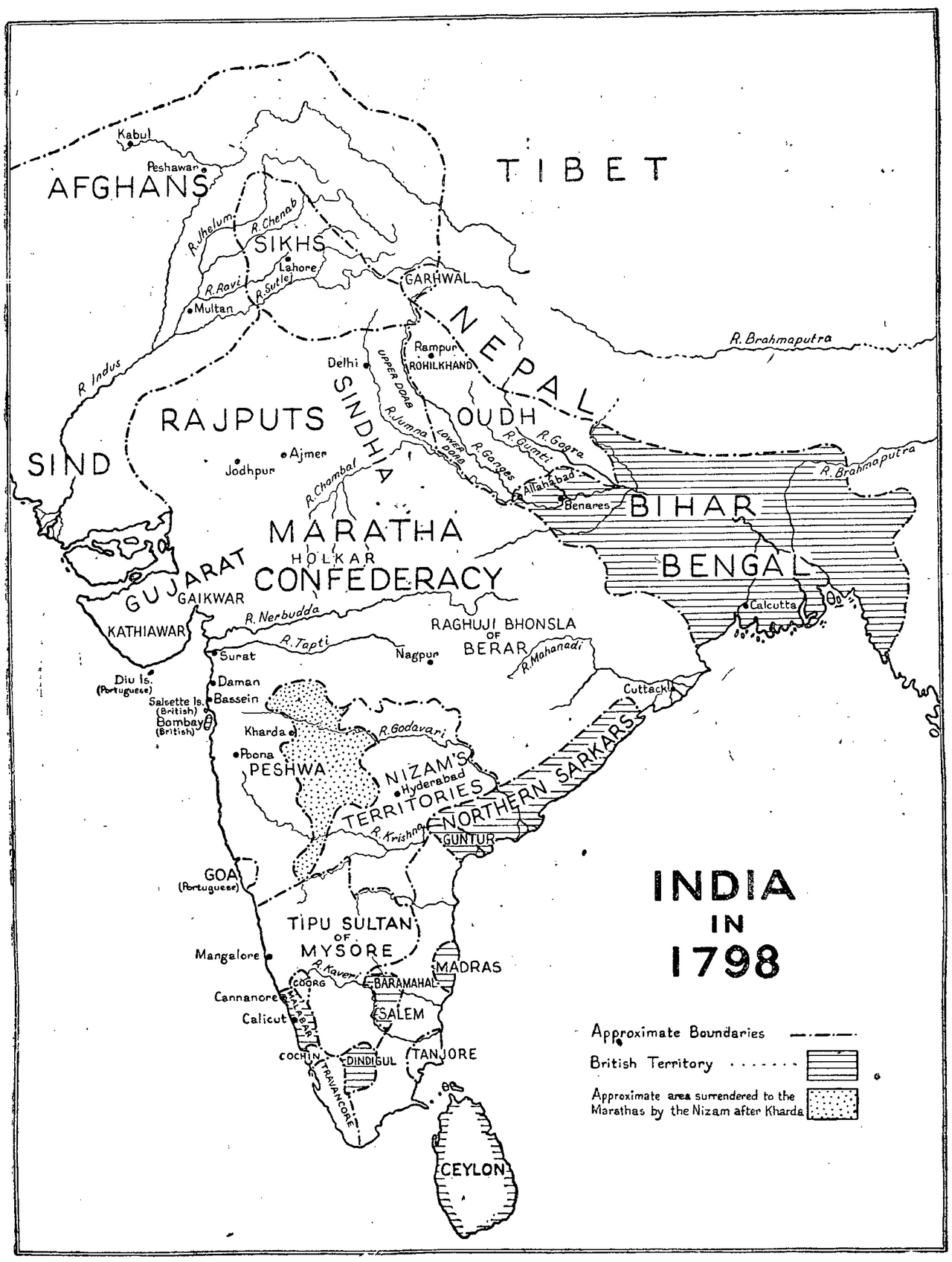

By the late 18th century, the Maratha Confederacy had expanded significantly across the Deccan under leadership figures such as Peshwa Bajirao I. Their campaigns reached deep into Berar, and they imposed the chauth (a fourth share of revenue) over territories including present-day Hingoli.

A major milestone in this expansion was the Battle of Kharda (also referred to as Khurla), fought in 1795 between the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad (refer to Ahilayanagar for more). The Nizam’s defeat resulted in the cession of large parts of Berar to the Marathas. Given Hingoli’s location within Berar, it likely came under Maratha influence during this period. According to the Parbhani district Gazetteer (1967), the Bhosales of Nagpur retained revenue rights in parts of Berar, which may have included areas in the present-day district.

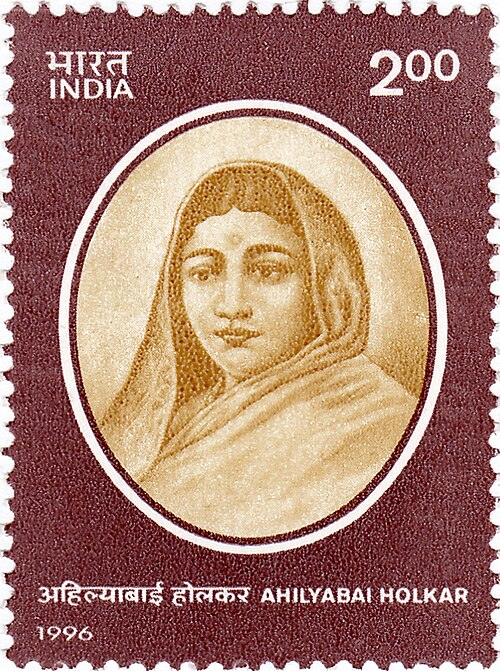

Restoration of Aundha Nagnath Mandir under Ahilyabai Holkar

This period also saw significant religious patronage under the Maratha state. One notable instance was the restoration of the Aundha Nagnath Mandir in Kalamnuri taluka (see more on it above or in Cultural Sites). The Mandir, it is said, had suffered damage in earlier military campaigns. Its restoration is credited to Ahilyabai Holkar, the Queen of the Malwa kingdom (1767–1795), who is known for commissioning the renovation of mandirs across India. The reconstruction of the mandir not only reinstated its spiritual significance but also reinforced the Maratha state’s role in preserving cultural institutions across the Deccan.

Shifting Alliances and the Rise of British Influence

Despite Maratha gains after the Battle of Kharda (mentioned above), power in the Deccan remained contested. In 1798, Asaf Jah II, the Nizam of Hyderabad, entered into a subsidiary alliance with the British East India Company. This agreement placed the Nizam under British protection in exchange for political and military concessions. British troops were stationed in Hyderabad territory, and while the Nizam retained formal sovereignty, administrative influence increasingly rested with the British.

The alliance was pivotal during the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars (1803–05, 1817–19). The defeat of the Marathas in these conflicts effectively ended their dominance, and territories such as Berar—including Hingoli—were integrated into the Nizam’s state under indirect British control.

The Nizams of Hyderabad Under the British Paramountcy

Hingoli under Nizam-British Administration

In 1798, Asaf Jah II, the Nizam of Hyderabad, entered into a subsidiary alliance with the British East India Company. This agreement, which placed Hyderabad under British protection, marked a turning point in the political dynamics of the Deccan. In exchange for military support, the Nizam ceded significant authority to the Company, including the right to station British troops within his territory. Hyderabad thus became the first princely state to formally accept British paramountcy.

From 1818 to 1853, the present Hingoli district was governed by the Nizam as part of the Berar province. The region was split administratively:

- South Berar, with Hingoli as its administrative headquarters, remained under Nizam rule.

- North Berar, with Buldhana as its headquarters, came under British control.

Though nominally under the Nizam, British officials played a key role in administration, particularly in revenue and policing matters. This shared authority arrangement shaped the region’s legal and institutional frameworks through the 19th century.

Reorganisation of the Hyderabad Contingent

Hingoli’s significance continued to grow in this period, particularly as a military centre. In 1826, the Hyderabad Contingent—a force raised jointly by the Nizam and the British—was reorganised. Hingoli became the base of a full military brigade, comprising two battalions of infantry, a company of artillery, and a detachment of cavalry.

Later, in 1903, this contingent was further formalised into four divisions: The Hingoli Brigade, along with divisions stationed at Bolarum (Secundarabad), Aurangabad (present-day Sambhaji Nagar), and Ellichpur (present-day Achalpur), helped secure the broader region. This military role not only ensured political stability but also influenced the urban structure of Hingoli town.

Mohalla Paltan

Interestingly, this military legacy can still be traced in the names of localities across the district. One such place is Mohalla Paltan. The neighbourhood, even today, bears visible signs of Hingoli’s military past during the colonial and princely periods. The term paltan means battalion and points to its clear association with the Hyderabad Contingent stationed in Hingoli. The contingent’s presence here, as part of the broader military arrangement under British paramountcy, likely shaped the development and layout of the area.

While today the locality functions as a residential neighbourhood, its older fabric still retains visible reminders of this earlier role. The narrow lanes and aged buildings in Mohalla Paltan include barracks, drill grounds, and officer quarters that once served military purposes. Among the better-known landmarks are Paltan Chowk, a square that was once used for parades and drills; Paltan Gate, which served as an entrance to the old cantonment zone; and Paltan Cemetery, where soldiers from both the Nizam’s and British periods are believed to have been buried.

Policing and “Thuggee” Suppression

Hingoli’s military status also perhaps positioned it as a key centre during the British campaign against thuggee, a term used by colonial officials to describe organized banditry. In 1833, operations were launched under Captain William Sleeman, who led the Thuggee and Dacoity Department. Hingoli became one of the first locations in the Deccan where suppression efforts are said to have begun.

Administrative Transfer and The 1853 Treaty

In 1853, a new treaty between the Nizam of Hyderabad and the British East India Company fundamentally altered the administrative landscape of the region. Under the terms of the agreement, the province of Berar—including the area now comprising Hingoli—was transferred to British administration. Though the Nizam retained nominal sovereignty over the territory, actual governance passed into the hands of British officers.

At the time, Hingoli was not a separate district but formed part of Parbhani within the Hyderabad State. As a result, most administrative references to the area in 19th-century records, including those of land revenue, policing, and military affairs, are found under Parbhani’s jurisdiction.

This arrangement remained in place during the Indian Revolt of 1857, when the Nizam chose to remain loyal to the British. According to the Hyderabad Provincial Series Gazetteer (1909), the Subsidiary Force and the Hyderabad Contingent played an active role in maintaining order across the state during this period. Their efforts were particularly visible in frontier areas like Hingoli, where British and princely forces often operated jointly.

Rise of Cotton Industry

Hingoli’s cotton economy began to grow in scale and prominence. Though cotton had been cultivated in the region for centuries, the late 19th century witnessed an increase in demand driven by both British industrial needs and the global expansion of cotton trade. Improved transport links and administrative attention to revenue-generating crops helped integrate Hingoli more deeply into wider economic networks.

The Imperial Gazetteer (1908) would later describe Hingoli as a “great cotton mart,” a phrase that captured its emerging status as a regional centre for cotton cultivation and trade. Cotton cultivation thrived particularly in the northern, more fertile parts of the district, while the southern region remained drier.

According to the Parbhani district Gazetteer (1967), Hingoli’s cotton was valued for its quality and was exported to several regions. B.R. Andhare (1977) also notes the district’s reputation for cotton and wheat cultivation. The sector remains active: in 2022–23, Hingoli reported 1.5 lakh hectares under cotton cultivation, with production estimated at 3 lakh bales.

Land Revenue

To support agriculture, a new land revenue system was introduced in 1866 which replaced the earlier contractor-based model. Inspired by the Ryotwari system, revenue was now collected directly from cultivators. This reform echoed similar changes across the Deccan during the colonial period.

By 1885, Hingoli and Kalamnuri talukas in the district are noted to have undergone a full land settlement. Tax rates were fixed for 15 years, based on soil type and productivity:

- Dry land: ₹1 to ₹5 per acre.

- Wet land: ₹3 to ₹4 per acre.

Education and Social Infrastructure

By the turn of the 20th century, Hingoli had a limited but developing education system. The Imperial Gazetteer (1908) reports three institutions, including a middle school and a girls’ school, with a combined enrollment of 230 students. While small, the presence of a girls' school is notable, reflecting early steps towards broader educational access under the Nizam’s administration, in collaboration with British educational reforms.

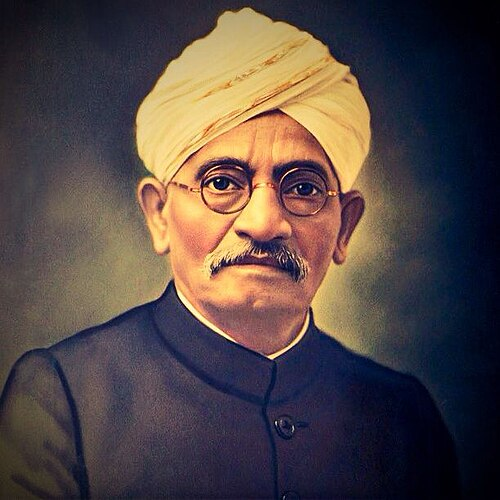

Notably, several individuals from the district also played a role in the development of education and participated in wider sociopolitical movements. Among these was Keshavrao Koratkar, who was born in Purjal village. Trained in law, Koratkar was active in advocating for Marathi as the medium of instruction. He played a significant role in the formation and support of local educational institutions across the Marathwada region. His activities were closely linked to ongoing discussions around language, access, and regional identity within the princely state. As a member of the Hyderabad State Congress, he also participated in efforts aimed at internal reform and public mobilisation.

Post Independence Era

Creation of the Hingoli District

After India’s independence in 1947, Hingoli underwent a series of administrative changes shaped by the broader reorganisation of states and territories across the country. Following the integration of the Hyderabad State into the Indian Union in 1948, the region, including Hingoli, came under Indian administration.

In 1956, as part of the States Reorganisation Act, Hingoli became part of the Bombay State. Four years later, in 1960, the creation of Maharashtra saw Hingoli continue under the jurisdiction of Parbhani district, consistent with earlier historical arrangements.

On 1 May 1999, a separate Hingoli district was carved out of Parbhani. The new district included five administrative units, namely, Hingoli, Kalamnuri, Sengaon, Aundha Nagnath, and Basamat. Each taluka became part of the district's civil and revenue administration following its establishment.

Sources

B. R. Andhare. 1977. A History of Marathwada (1818-1972). Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture.

Cambridge History Of India. 1971. The Mughul Period. Vol. 4. S. Chand & Co., New Delhi.https://archive.org/details/CambridgeHistory…

Census of India, 2011, Maharashtra. 2014. District Census Handbook, Hingoli. Series 28, Part 12 B. Directorate of Census Operations, Maharashtra, India.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

Charles Lewis Tupper. 1893. Our Indian protectorate; an introduction to the study of the relations between the British government and its Indian feudatories. Longmans, Green and Co., London and New York.https://archive.org/details/cu31924024061933

District Mining Officer. 2020-21. District Survey Report. Hingoli, Maharashtra.https://environmentclearance.nic.in/Download…

Government of Maharashtra. 1977. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Aurangabad District. Gazetteers Department, Bombay.

Hingoli Tourism. Aundha Nagnath Temple. Marathwada Tourism. https://www.marathwadatourism.com/en/aundha-…

Mirza Mehdy Khan. 1909. Imperial Gazetteer Of India: Provincial Series - Hyderabad State. Superintendent Of Government Printing, Calcutta.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

P. Setu Madhava Rao ed. 1967. Parbhani District Gazetteer. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationery and Publications, Maharashtra State, Bombay, India.https://archive.org/details/dli.csl.3369/mod…

Pravin J. Nadre. 2020. Parbhani and Hingoli districts: Ancient times. Vol. 7, Issue 12. Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ).http://www.aiirjournal.com/uploads/Articles/…

Sunil Purushotham. 2021. From Raj to Republic: Sovereignty, Violence, and Democracy in India. Stanford University Press.http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=31562

William Hunter. 1908. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India. Vol. 13. Caldron Press, Oxford.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.