Contents

- Ancient Period

- Stone Age Tools at Changdev

- The Upper Palaeolithic Site at Patne

- The Settlements at Bahal and Tevekada

- Early Mentions of the Purna River

- Political Shifts and Early Dynasties

- The Abhiras and the Ahirs

- Chalukyas, Sendrakas, and the Mundkhede Plates

- Rashtrakutas and their Grant at Pachora

- Nirkumbhavansis of Patna and Bhaskara II

- Yadavas and Their Hemadpanthi Mandirs

- Medieval Period

- Rise of the Farooqi House

- Mughal Rule and Mentions in the Ain-I-Akbari

- The Marathas in Khandesh

- Holkar’s Campaigns and the Fragmentation of Maratha Authority

- Mercenary Presence and Gulzar Khan of Lasur

- Raids and Resistance in the Northern Hills

- Colonial Period

- Bhil Agencies and their Governance

- Parola Incident and Dispossession of the Jhanshikar Family

- Territorial Expansion and the Gwalior Treaty (1844)

- Resistance at Yawal Fort

- Survey Resistance in Erandol

- The First War of Independence, 1857

- Parola and its ties to the Rani of Jhansi

- Railways and Bhusawal as One of the Largest Railway Junctions

- Division of Khandesh District and the Role of Jalgaon

- Floods & Environmental Strain

- Post-Independence

- Sources

JALGAON

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Jalgaon district lies in the northern part of Maharashtra and forms a part of the Nashik Division. It occupies a wide stretch of the Tapti River valley, along the northern edge of the Deccan plateau, and shares its northern boundary with Madhya Pradesh. The region is of considerable antiquity, with archaeological evidence indicating human habitation as early as the Stone Age. Early textual and oral traditions also associate the area with centres of learning, and it is believed that the mathematician and astronomer Bhaskaracharya II lived and worked in this region.

Over time, the territory came under the control of successive dynasties, including the Mauryas, Satavahanas, Mughals, and Marathas. During the colonial period, it was incorporated into the Bombay Presidency as part of the East Khandesh district. This administrative arrangement continued into the early years following independence. In 1960, following the reorganisation of states, Jalgaon was constituted as a separate district within the newly formed state of Maharashtra.

Ancient Period

Stone Age Tools at Changdev

Jalgaon’s past stretches far into prehistory, and one of the earliest traces of human presence here comes from the banks of the Tapi and Girna rivers. Along the banks of the Tapi and Girna rivers, particularly at Changdev in present-day Muktainagar taluka, stone tools such as Acheulean hand-axes and cleavers have been discovered. These large, bifacial tools were likely used for cutting and processing plant or animal material, and their presence points to the movement of early hominin groups through the riverine landscapes of north Maharashtra.

The Upper Palaeolithic Site at Patne

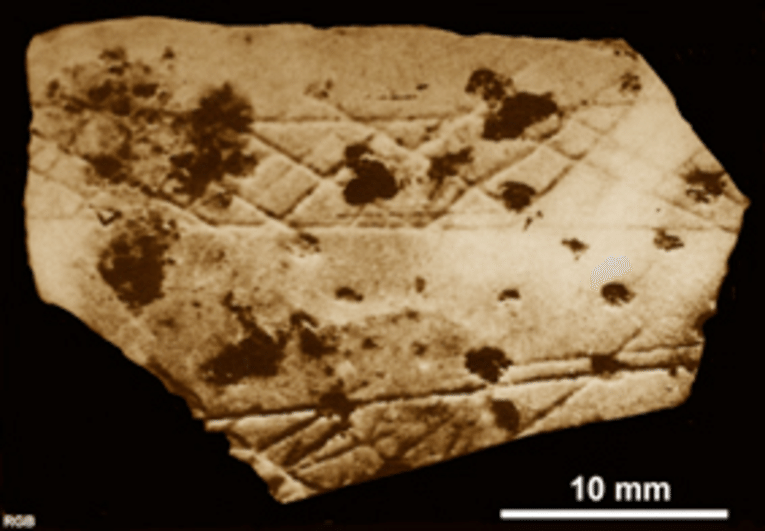

Another significant trace comes from Patne village, which is located in the present-day Chalisgaon taluka. Excavations carried out here have uncovered Upper Palaeolithic material, most notably an engraved fragment of ostrich eggshell. This fragment features a deliberate criss-cross pattern, framed by two horizontal lines, and is estimated to be around 25,000 years old.

The engraved ostrich eggshell from Patne is notably one of the earliest and most securely identified examples of Upper Palaeolithic symbolic expression in India. Alongside the decorated fragment, the site also yielded ostrich shell beads and stone tools typical of this period, contributing to broader understandings of prehistoric habitation in western India.

The Settlements at Bahal and Tevekada

Further traces of early habitation in the Jalgaon region appear during the Chalcolithic period. Excavations at Bahal and Tekevada, both located along the banks of the Girna river, have revealed a range of artefacts that point to settled life and craft activity during this time. Among the most prominent finds is a distinctive type of painted black-on-red pottery, often decorated with geometric patterns. Alongside the ceramics, archaeologists also uncovered beads made from semi-precious stones, suggesting the use of ornamental objects within these communities.

Though fewer in number, copper artefacts were also recovered from the sites, indicating early use of metal tools or objects, likely alongside continued reliance on stone implements. These finds reflect a gradual transition towards more permanent forms of settlement, with knowledge of ceramics, metallurgy, and possibly trade.

In 1960, another excavation, this time along the banks of the Waghur River, brought to light painted pottery fragments and a handful of burial remains. These suggest that mortuary practices were beginning to take shape in the region by this time.

Interestingly, later layers at the Bahal site have yielded Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) and a small number of coins, materials typically associated with the early historic period, around the 4th century BCE. Their presence points to a continuity of occupation at the site and the gradual integration of Jalgaon’s settlements into broader cultural and economic networks that emerged in this part of the Deccan region during this time.

Early Mentions of the Purna River

Many other sites in the present-day district also attest to its antiquity. The Purna River, a tributary of the Tapti, is one of these. Its name comes from Sanskrit, where purna means "complete." In earlier times, the river was known by older names such as Payoshni or Paisani, and it is mentioned in the epic Mahabharat as part of the territory of the ancient Vidarbha Kingdom.

References like these suggest that the region, or at least parts of it, were known in early Indian literature and may have held some cultural or geographic importance in that period; it also indicates that the river was known and named in early textual traditions. Today, the river continues to play an important role in Jalgaon’s agriculture, especially in areas like Muktainagar and Malkapur. Its water supports farming in an otherwise dry region.

Political Shifts and Early Dynasties

Over time, the region that now forms Jalgaon district came under the influence of several political powers that shaped the history of Khandesh and the wider northwestern Deccan. While early records specific to Jalgaon are limited, a combination of archaeological remains and literary references helps trace its place within broader regional developments.

Between the 4th and 2nd centuries BCE, Buddhism appears to have flourished in this region. While no major Buddhist cave complexes are located directly within Jalgaon district, its proximity to sites such as Ajanta, Ellora, and Pitalkhora (all of which lie in the present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district) suggests that Buddhist ideas and practices likely spread into the area. Notably, inscriptions found in the Pitalkhora caves mention and suggest that Buddhist patrons from Paithan (in present-day Sambhaji Nagar district) exercised control over neighbouring regions, possibly including parts of present-day Jalgaon district too.

Around this time, the region was likely under the rule of the Andhrabhrityas, a group widely identified with the Satavahanas or their feudatories. The Satavahanas began consolidating power in the Deccan around the 2nd century BCE, eventually building an empire that extended across large parts of present-day Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana. Although their rule did not cover a single unified territory, it stretched across important trade routes and administrative centres, including Khandesh, to which Jalgaon has long been geographically and politically connected.

An inscription found in the Nashik caves (Nashik district, Maharashtra) mentions that the first two Satavahana rulers, Simuka and Kanha, controlled territories such as Paithan (Sambhaji Nagar district), Nashik, and Khandesh. This suggests that Jalgaon, situated within this wider zone, likely fell under their influence as well. The Satavahanas continued to rule until the later part of the 1st century CE, when they were defeated by Nahapana, a ruler of the Western Kshatrapas (based in regions of present-day Gujarat and western Maharashtra). Following their defeat, the Satavahanas lost control over key parts of their northern territory, including the broader Khandesh region.

The Abhiras and the Ahirs

Following the decline of the Satavahanas in the early centuries of the Common Era, the Abhiras (also referred to as Ahirs) rose to prominence in parts of western India. According to the district Gazetteer (1962), the Abhira dynasty, led by rulers such as Ishwarsena, may have controlled sections of Khandesh, including parts of what is now Jalgaon district, between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE.

The Abhiras are often identified with the Gavali or Gwali community, traditionally associated with cattle herding and pastoralism. Some scholars argue that they were ancestors of the present-day Ahir community, now dispersed across many regions of India. While their exact origins remain debated, historian H. S. Thosar (1990) suggests the Ahirs may have migrated from eastern Iran, with their arrival and rise in Khandesh dated around 419 CE.

Although no inscriptions directly referencing Abhira rulers have yet been discovered within Jalgaon district, records from neighbouring regions suggest they held authority over the wider area. At the same time, the long-standing presence of the Ahir community in the district, distinct from the royal dynasty but possibly linked by origin, has been preserved through local traditions, social structure, and language.

One of the most enduring legacies of the Ahirs in Jalgaon is the Ahirani language, which is still widely spoken across the district’s northern parts. Ahirani is traditionally associated with the Ahir community, and according to the Census of India (2011), around 12.12% of Jalgaon’s population speaks Ahirani as their first language, especially in Chalisgaon, Jamner, and surrounding talukas (refer to Language for more). Notably, some view this continuity as indicative of a strong Ahir and Abhira legacy dating back to the early historic period.

Chalukyas, Sendrakas, and the Mundkhede Plates

Between the 4th and 5th centuries CE, the Vakataka dynasty expanded its dominion across parts of the Deccan plateau. It had two principal branches, of which the Vatsagulma line, with its capital at Washim, emerged as a significant centre of power. According to the district Gazetteer (1962), this branch exercised considerable influence across the Khandesh region, extending its political reach well beyond its immediate seat. The broader presence of the Vakatakas in the Deccan is also evident in the Ajanta Caves in present-day Sambhaji Nagar, where several inscriptions attest to their patronage in the excavation and embellishment of these monumental structures.

After the Vakatakas, the Chalukyas of Badami emerged as the dominant power in the western Deccan. Inscriptions found in Nashik suggest their expansion into the Khandesh region during the 6th and 7th centuries CE. Within Jalgaon, copper plates discovered in Mundkhede village (Jalgaon district) refer not to the Chalukyas directly, but to a local lineage connected to them, the Sendrakas. These plates record land grants issued by rulers such as Jayasakti Sendrak, suggesting that the family held authority along Jalgaon’s western periphery.

Later inscriptions found in Mehunbare in the district mention successors such as Devashakti, Vairadev, and Dandiraj, which has made Historians suggest that they might have ruled over some regions in Khandesh for a little over fifty years.

Rashtrakutas and their Grant at Pachora

In the mid-8th century CE, the Rashtrakutas rose to power in the Deccan, succeeding the Chalukyas of Badami. Their empire extended across central India, Gujarat, the Konkan coast, and Khandesh, and traces of their rule can be found in the present-day Jalgaon district.

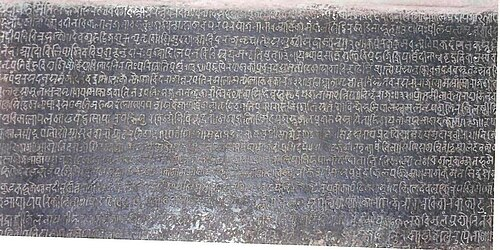

A copper plate inscription dated to Saka 732 (809 CE), from the reign of Govinda III (also known as Kritinarayan), was discovered near Bhadgaon, in Pachora taluka. This inscription records the donation of a village named Bhaulavara, located in the Bahula vishaya, a territorial unit believed to have encompassed parts of modern Pachora and Bhadgaon regions. The inscription, written in Sanskrit and engraved in the formal script of the period, hints at the integration of the region into the Rashtrakuta administrative and political sphere.

Nirkumbhavansis of Patna and Bhaskara II

Between approximately 500 and 1200 CE, Jalgaon and Khandesh came under the sway of several local dynasties. According to the Khandesh Gazetteer (1880), two noteworthy ruling groups during this period were the Taks of Asirgad and the Nirkumbhvanshis of Patan. Of these, the Nirkumbhvanshis were based at Patan (present-day Jalgaon district, Maharashtra), and are recorded to have governed over about 1,600 villages in southern Khandesh.

The internal arrangements of the Nikumbhvanshi administration are not extensively documented. However, two chiefs, Sonhadev and Hemadiddev, are remembered in local tradition and are credited with a degree of patronage extended to the study of astronomy and astrology. Land is said to have been granted under their rule for the establishment of a learning centre dedicated to these disciplines, suggesting a limited but notable engagement with intellectual activity.

Fascinatingly, the name of Bhaskaracharya, the celebrated astronomer and mathematician of the twelfth century, is commonly associated with the present-day district during this period. Tradition holds that he resided for a time at Patnadevi, a village in Chalisgaon taluka, situated in a secluded valley and approached through forested ground. Whether he was born in the vicinity or merely dwelt there for purposes of study is not known with certainty. The site lies near the ancient Mandir of Siddheshwar, and is said to have offered conditions favourable to quiet observation.

Yadavas and Their Hemadpanthi Mandirs

By the early years of the thirteenth century, the authority of the Nikumbhvanshi line had begun to wane, and by 1216 CE, their influence in the region appears to have diminished considerably. In the decades that followed, administrative control over parts of southern Khandesh passed into the hands of officers acting under the Yadavas of Devagiri.

The Yadava period, though comparatively brief in the district’s recorded history, left behind architectural traces of some note. It was during this time, and particularly under the minister Hemadri, that the style of temple construction now referred to as Hemadpanthi came into general use. The method is marked by the use of locally quarried stone, laid without mortar, and a preference for restrained, functional design over decorative elaboration.

Structures of this character survive at several sites within Jalgaon district, including Patan, Shendurni, Lohara, Kurhad, and Waghali. Of these, one of the earliest dated monuments possibly linked to this period is the Siddhanath Mandir at Waghli (present-day Chalisgaon taluka). It is noted in the New Indian Antiquary (1947), “it was built in S. 991 at the latest (1069 A.D.) by Govindaraja (and his wife), a Maurya feudatory of the Mahamandaleshvara Seuna of the Yadavas.”

Another prominent monument from this era in the district is the Changdev Maharaj Mandir, which is situated in the village of Changdev. This Mandir is dedicated to Changdev Maharaj, who is a sant of considerable regional repute and is known variously as Changa Deva, Changadeva, or simply Changa in textual sources. He is believed by legend to have lived for 1,400 years and occupies a significant place in regional spiritual traditions.

The original Mandir at Changdev is believed to date from the twelfth or thirteenth century. It was later rebuilt under the patronage of Queen Ahilyabai Holkar in the latter part of the eighteenth century. In recent years, conservation work has been undertaken by the Archaeological Survey of India in recognition of the structure’s cultural and historical value.

Medieval Period

In the closing years of the 13th century, the armies of Alauddin Khilji moved southward from Delhi, targeting the kingdom of Devagiri, ruled by the Yadava king Ramchandra. During this campaign, the Delhi forces overran significant portions of the Deccan. Around this time, according to the district Gazetteer (1962), the region now forming Jalgaon district was under the control of Chauhan chieftains, while further east, the fort of Asirgad (which lies nearby) was held by Ishatpal of the Hara dynasty.

After defeating Ramchandra, Alauddin returned north, but not without incident. On his return march, he encountered resistance from the Chauhans in Khandesh. A confrontation followed in which the Chauhan chief was defeated, and Khandesh, including outlying areas like present-day Jalgaon, fell briefly under Delhi’s control. The Gazetteer (1962) notes that Alauddin also took possession of the Asirgad fort during this campaign. However, other accounts suggest this was a passing occupation and not a formal annexation.

The Delhi Sultanate’s involvement in the region deepened in 1306, when Alauddin sent Malik Kafur, a senior military commander, to again extract tribute from Ramchandra. The Yadava ruler complied. He was escorted to Delhi and reinstated as a tributary with expanded authority, under the condition that he remain loyal to the Sultanate.

In 1311, when Khilji forces launched a fresh campaign against the Kakatiyas of Warangal, Ramchandra provided logistical support and quarters at Devgiri. But this alliance was short-lived. In 1312, Ramchandra's son, Simhana III (also known as Shankardev), assumed power and rejected Delhi’s authority. He was defeated and killed by the Khilji forces. Devagiri was brought under firmer control, and Delhi began using it as a southern garrison.

In the aftermath of these events, Harpal Dev, Ramchandra’s son-in-law, mounted a revolt. He ceased paying tribute to Delhi and seized several forts and strongholds from the Sultanate’s garrisons. Around this time, Alauddin Khilji died (1316), and his successors, Malik Kafur, Shihabuddin, and Mubarak Shah, faced internal instability. As the central power weakened, regions on the frontier, such as Khandesh, appear to have begun to operate with greater autonomy.

By this time, according to the Khandesh Gazetteer (1880), much of Khandesh, perhaps even parts of Jalgaon, were under the control of a chief based at Asirgad. The Asirgad Raja governed from this formidable hill fort located in the Satpura range, now in Madhya Pradesh, and exercised independent authority over the surrounding territory.

The Sultanate’s weakening grip on the Deccan region also coincided with new powers rising with the gradual emergence of the Bahmani Sultanate in the south and the Farooqi dynasty in Khandesh.

Rise of the Farooqi House

In 1370 CE, Malik Ahmad, known as Malik Raja Faruqi, received the provinces of Thalner and Karanda (near present-day Dhule) from Fīrūz Shah Tughluq of Delhi, and subsequently established himself in the region that came to be known as Khandesh. He soon asserted independence, marking the beginning of the Farooqi dynasty, which would maintain control over the region for more than two centuries. Malik Raja’s early seat lay within the limits of what is now Dhule district (see Dhule District), from which he extended his influence across much of Khandesh. Although the later Farooqi state came to be centred at Burhanpur and Asirgad, areas of present-day Jalgaon district probably fell within its sphere of control, owing to their proximity to key routes connecting the Tapi valley and the northern hill forts and their location within the Khandesh region.

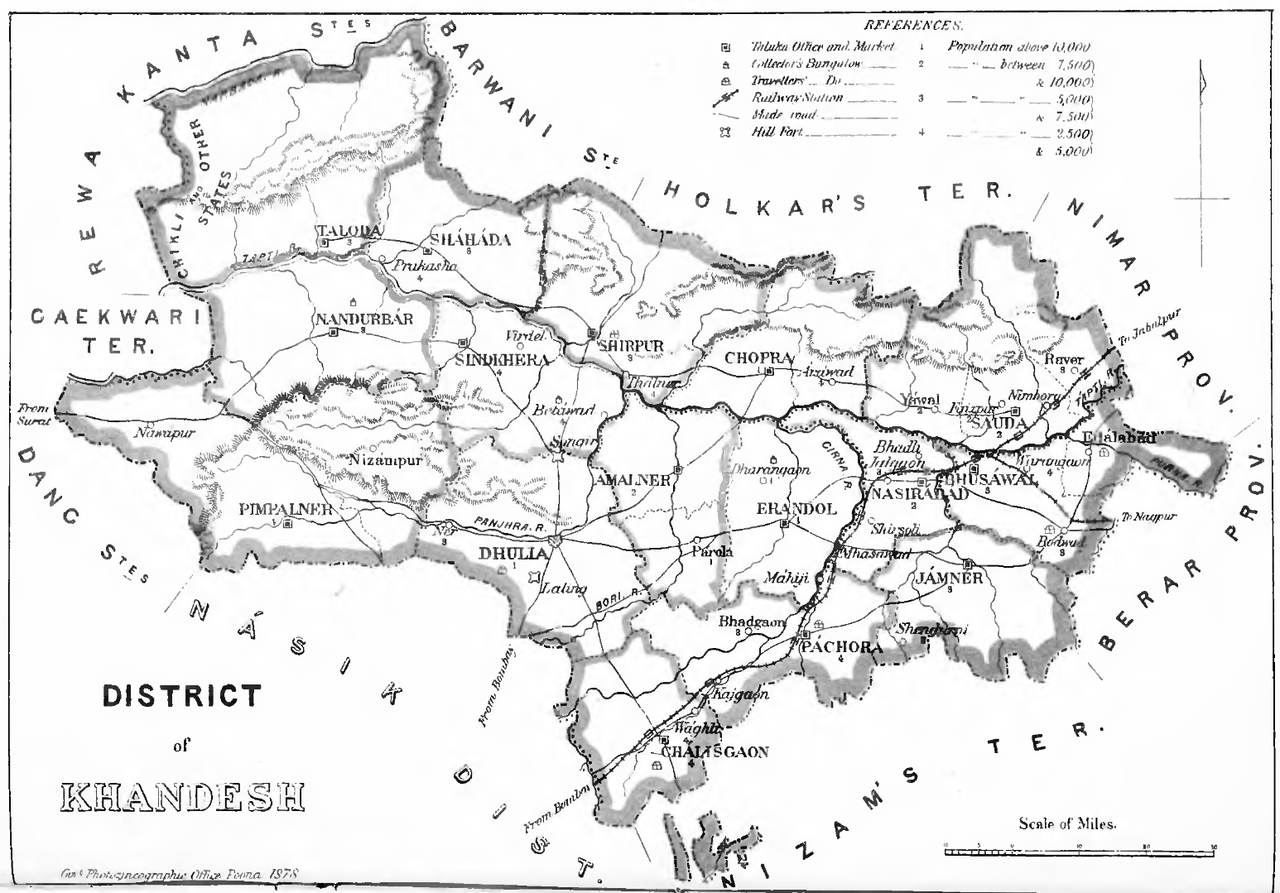

Mughal Rule and Mentions in the Ain-I-Akbari

With the decline of the Farooqi dynasty in the closing years of the sixteenth century, the Khandesh region passed under direct Mughal control. In 1600 CE, following the annexation of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, Emperor Akbar incorporated Khandesh into his administration. He reorganised the newly acquired territories into the subahs of Ahmadnagar, Berar, and Khandesh. The present Jalgaon district fell under the jurisdiction of the Subah of Khandesh.

Notably, mentions of this inclusion are found in the Ain-i-Akbari, the administrative compendium compiled by Abul Fazl. Among the locations recorded is Changdeo, identified with the present-day village of that name in Muktainagar taluka. Describing its religious significance and geographic setting, Abul Fazl notes:

“Chnagdeo is a village near which the Tapti and the Purna unite, and the confluence is accounted a place of great sanctity. It is called Chakra Tirth. Adjacent to it is an image of Mahddeo. They relate that a blind man carried about him an image of Mahadeo, which he worshipped daily. He lost the image at this spot. For a time, he was sore distressed, but forming a similar image of sand, he placed it on a little eminence and adored it in a like spirit. By a miracle of divine will, it became stone and exists to this day. Near it, a spring rises, which is held to be the Ganges. An ascetic by the power of the Almighty was in the habit of going to the Ganges daily from this spot. One night, the river appeared to him in a dream and said, ‘Undertake these fatigues no longer; I myself will rise up in thy cell.’”

This passage establishes the continued spiritual importance of the region and reflects the Mughal administration’s recognition of its religious geography.

The Ain-i-Akbari also refers to Choprah, identified with the present-day Chopda tehsil in northern Jalgaon. Described as both prosperous and sacred, Abul Fazl writes, “Choprah is a large flourishing town, near which is a shrine called Ramesar at the confluence of the Gima and the Tapti. Pilgrims from the most distant parts frequent it.”

These accounts confirm that multiple sites now within the Jalgaon district were administratively recognised and culturally prominent before and even during the Mughal period.

In 1634, the region was drawn into the wider currents of some major conflicts in the Mughal court. Khan Jahan Lodi, formerly governor of the Deccan, rebelled against Emperor Shah Jahan after falling into disfavour. Supported by Darya Khan Rohilla, he led a campaign through Khandesh, during which several towns and villages were attacked. Among those affected were Erandol and Chalisgaon, both located within the present boundaries of Jalgaon district. The disturbances marked one of several episodes in which the area was exposed to the political and military upheavals of the wider Deccan.

At the same time, the region experienced a severe famine. Between 1630 and 1632, a succession of failed monsoons led to crop failures across the Deccan plateau. The resulting food shortage caused widespread migration, loss of life, and economic stagnation. Jalgaon, like much of Khandesh, likely saw entire communities leave or collapse during these years.

The Marathas in Khandesh

By the early 18th century, Mughal authority in Khandesh had begun to weaken. As regional powers asserted themselves across the Deccan, the Marathas expanded steadily into northern Maharashtra, including parts of the present-day Jalgaon district.

Amid this decline, new rivalries emerged. One of the principal challengers to Maratha influence in the region was the Nizam of Hyderabad, a position created by Mughal-appointed governors who had gradually become independent. Nizam Ali Khan, the second ruler of the Hyderabad state, inherited this contest in the mid-18th century.

In 1760, after being defeated by Peshwa commander Sadashivrao Bhau, Nizam Ali ceded control of the Asirgad fort (Madhya Pradesh) and nearby territories to the Marathas. Though some of this land briefly returned to the Nizam after the Maratha setback at Panipat in 1761, the Peshwas soon reasserted control. It is mentioned in the district Gazetteer (1962) that “the lately ceded parts of Khandesh were restored to Nizam Ali,” but “he was forced to restore the territory to the Peshwa very soon.” By this time, areas along the Tapi valley, now part of Jalgaon district, were under Peshwa administration.

Holkar’s Campaigns and the Fragmentation of Maratha Authority

By the end of the century, the power of the Peshwas was further weakened by the emergence of rival Maratha houses. In 1797, Tukoji Holkar, chief of the influential Holkar family of Indore, passed away. His son, Yashwantrao Holkar, soon rose to prominence. Between 1800 and 1803, his forces traversed Khandesh repeatedly, including through Jalgaon, as he challenged both the Peshwa and other Maratha claimants to power.

In 1802, he set up camp at Thalner, a strategic fort in Jalgaon, from where he mounted further movements toward the south. As Holkar advanced through the Kasarbari Pass near Chalisgaon, reports described his passage as both military and destructive. It is notably written in the District Gazetteer (1962) that “Passing through Jalgaon district on his way north, Holkar ruined it as utterly as he had before ruined the other parts of Khandesh.”

Several settlements bore the brunt of these campaigns. Raver was sacked, and in Sultanpur (present-day Nandurbar), a confrontation with local chief Lakshmanrao Desai led to the town being plundered. Holkar received support from regional actors, including the Bhil chief Jugar Naik, who operated out of Chikli in the Satpuda foothills.

Mercenary Presence and Gulzar Khan of Lasur

By the early nineteenth century, much of Jalgaon district lay outside the effective control of any central authority. The weakening of the Maratha state had given rise to a range of local powers, including mercenary bands, indigenous tribal chiefs, and semi-autonomous strongmen. The district Gazetteer (1962) notes that, “Since the Maratha power began to totter, the greater part of the Khandesh province had been usurped by Arab colonists... having already all the petty chiefs, whom they served as mercenaries, more or less under their domination.”

One of the most prominent among these local figures was Gulzar Khan, who held the fort of Lasur, located northwest of Chopda in present-day Jalgaon district. Backed by a contingent of Arab mercenaries, he maintained de facto control over a small territory. His son, Alliyar Khan, operated from Chopda. The Gazetteer (1962) records that Gulzar Khan “used to let them [the Arabs] loose on the country round,” and that his rule soon became a threat to neighbouring landholders.

As the Peshwa’s authority waned, Gulzar Khan's position became increasingly unstable. His reliance on Arab troops exceeded his ability to pay them, and in lieu of wages, the mercenaries were allowed to plunder the surrounding countryside. In response, a number of local chiefs formed a league against him. In the ensuing conflict, both Gulzar Khan at Lasur and Alliyar Khan at Chopda were assassinated by their own Arab soldiers.

Gulzar Khan’s surviving son, Alif Khan, sought refuge with Suryajirao Nimbalkar of Yawal, a nearby stronghold in Jalgaon district. The Nimbalkars supplied him with a contingent of Karnatak mercenaries, who gained entry into Lasur Fort under the pretext of wage collection. Once inside, they turned on the Arab garrison and executed them. However, instead of returning the fort to Alif Khan, they retained it in the name of the Nimbalkars.

Alif Khan, now abandoned, allied himself with Bhils and turned to open plunder in the surrounding countryside. Lasur Fort remained under Nimbalkar control until it was formally surrendered to the British in 1818, reportedly for a sum of Rs. 10,000.

Raids and Resistance in the Northern Hills

This period also witnessed a resurgence of Bhil and Koli activity in the hill tracts of Satpuda and Ajintha, both located within Jalgaon district. The collapse of central administration allowed these communities to reclaim control over key passes, trade routes, and minor forts. The Gazetteer (1962) mentions that “Among the hill tribes were the Bhils whose chiefs commanded the passes, where their power was considerable.”

These groups levied tolls, interfered with revenue collection, and resisted external authority. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, large parts of northern Maharashtra, including Jalgaon, had slipped into disorder.

The Pindharis, who were raiders loosely associated with Maratha patronage, entered the district in 1816, aided by Bhils familiar with the terrain. They crossed into Jalgaon via the Asirgarh Pass (now in Burhanpur district, Madhya Pradesh), and carried out a series of raids. One of their principal targets was Gandhi, a town located six miles northeast of Amalner, described in the Gazetteer as “the first place of the Gujarat Shravak Vanis in Khandesh.”

The raids were marked by severity. By 1817, large portions of Jalgaon district were in disarray. Villages were razed or abandoned, and roads were considered unsafe except under armed escort. British reports from the period described the scale of devastation as “almost unexampled... even in Asia.”

Although the British annexed Khandesh in 1818, the hill tracts continued to resist formal rule. The Gazetteer records that, “Smarting under the repeatedly broken pledges of the former Native Government, and rendered savage from the wholesale slaughter of their families and relations, the Bhils were more than usually suspicious of a new government of foreigners.”

The assertion of British control was thus gradual and uneven, particularly in the remote and upland parts of the district.

Colonial Period

Following the conclusion of the Third Anglo-Maratha War in 1818, the region of Khandesh, including present-day Jalgaon district, was brought under the administration of the Bombay Presidency. Although Peshwa Baji Rao II surrendered in June of that year, various parts of Khandesh continued to experience intermittent disturbances in the months that followed. It had remained one of the more remote districts under Maratha influence and was among the last to be formally occupied by British forces.

The administrative integration of the area proceeded gradually. During this period, Jalgaon appears in official records for the first time as a distinct settlement. The Bombay Presidency Gazetteer (1896) notes that Jalgaon was formally recognised as a town during the initial phase of British consolidation in Khandesh.

Bhil Agencies and their Governance

Following the British annexation of Khandesh in the early 19th century, colonial authorities sought to reorganise the governance of its more autonomous and frontier regions, particularly those inhabited by indigenous communities such as the Bhils. In response to both geographic and sociopolitical challenges, a tripartite administrative structure known as the Bhil Agencies was established, which was supervised by a British officer.

- The northwest agency included areas like Nandurbar, Sultanpur, Pimpalner (Dhule district), and the Dangs (Gujarat).

- The northeastern agency comprised Amalner, Nasirabad, Chopda, Yaval, Savda, and Erandol, places that now fall within the present-day Jalgaon district.

- The southern agency oversaw Jamner, Bhadgaon, Chalisgaon, and parts of the Satmala range (all of which again fall within the boundaries of the present-day Jalgaon district).

These agencies were tasked with maintaining order through what were then described as “gentler measures.” In the northeast, a local paramilitary unit known as the Bhil Corps was formed.

Parola Incident and Dispossession of the Jhanshikar Family

Yet the imposition of external authority was neither smooth nor uncontested. Resistance to these changes had existed from the outset, and discontent remained visible across the early decades of British rule. In 1821, a notable disturbance broke out in and around Parola (in present-day Jalgaon district), where local opposition to British presence intensified. During the unrest, an assassination attempt was made on Captain Briggs, who was a British officer stationed in the region.

The British placed the blame for the incident on Lalbhau Jhanshikar, a local figure of considerable repute and holder of the Parola fort. In retaliation, the British confiscated the fort from the Jhanshikar family.

Territorial Expansion and the Gwalior Treaty (1844)

By the early 1840s, the Khandesh district had been under British control for more than two decades, but its boundaries remained ambiguous, and their hold over it only remained partial. According to the district Gazetteer (1962), Parts of northern Khandesh, including Yawal, Chopda, Pachora, and Lohara, were still held by the Scindias of Gwalior, who retained these lands under earlier arrangements. (Notably, in a reversal of the 1818 annexation, these areas were formally handed over to the Gwalior State in 1837, which had held them previously.)

In 1844, the British concluded a treaty with the Gwalior State, formalising the transfer of these remaining tracts to the Bombay Presidency. The agreement was part of a broader realignment of territorial control following internal instability in Gwalior and the increasing consolidation of British influence across central India. With this treaty, the boundaries of Khandesh district were extended eastward, incorporating fertile, well-settled lands into the existing administrative structure.

While the transfer was orderly on paper, its implementation faced challenges on the ground. In some locations, British officers encountered delays and refusals. The most notable of these took place in Yawal, where the process of taking charge was openly resisted.

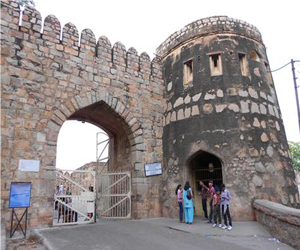

Resistance at Yawal Fort

At the time of the handover, Lalji Sakharam, also known as Lala Bhau, was serving as mamlatdar (local revenue officer) in Yawal. Refusing to recognise the authority of the new administration, he withdrew with his staff and a force of approximately three hundred men into the local Yawal Fort, also known as Nimbalkar Fort. The fort had served as a stronghold under previous local rulers and remained structurally defensible.

This act of resistance temporarily stalled the extension of British control over the area. Though it did not escalate into open conflict, it required a show of authority to resolve. Eventually, the fort was surrendered, and the area was brought under direct administration.

Smaller but similar forms of opposition were recorded in Lohara and Pachora, both of which were also affected by the territorial reorganisation. In these places, resistance was less concentrated and more dispersed. Local officials and communities expressed their discontent through non-cooperation, delaying revenue payments, obstructing survey work, or refusing instructions issued by the new district authorities.

Unlike in Yawal, there was no fortified standoff, but the delays reflected broader unease with the shifting administrative order. As in other regions incorporated during this period, the consolidation of authority was gradual and often met with local hesitation.

Survey Resistance in Erandol

In the early 1850s, the British administration introduced a land demarcation programme across Khandesh. As part of the initiative, landholders were instructed to mark their property boundaries with permanent stone markers. The goal was to standardise landholding records, facilitate taxation, and reduce disputes. However, the measures disrupted long-standing local practices, particularly in areas where customary land rights were loosely defined or communally managed.

In Erandol, the survey was met with open resistance. The population objected to the requirement to erect boundary stones, seeing it as intrusive and unnecessary. Tensions escalated when a subhedar, a mid-level official involved in the survey, was captured by the residents. They refused to release him unless the land survey was cancelled. The detention was a deliberate attempt to halt the process and assert local control over land-related decisions. Though brief, the incident signalled the depth of local dissatisfaction with the new system.

Elsewhere in the district, resistance took on a more sustained form. In Faizpur and Savda, villages refused to comply with survey instructions, withheld tax payments, and began organising alternative forms of local governance. These actions marked a shift from protest to defiance. British officials noted that some communities had stopped acknowledging district orders altogether.

Unlike Erandol, where a single event prompted negotiation, the situation in Faizpur and Savda continued for months. The resistance disrupted not just the survey, but regular revenue operations. The establishment of parallel systems of control in these areas posed a direct challenge to district authority.

In December 1852, the administration responded with a targeted operation. Troops, including members of the Bhil Corps, were deployed to suppress the movement. Several leaders of the resistance were arrested, and control was restored in the affected villages.

In Chopda and nearby areas, similar opposition forced survey teams to pause or relocate, though without the same level of confrontation.

The First War of Independence, 1857

In 1857, as uprisings spread across northern and central India, the Khandesh region too witnessed a series of local revolts. Much of the unrest in the district centred around Bhil communities, whose leaders had, until recently, been employed in the service of the colonial government, either as informants, trackers, or local auxiliaries.

Of these, one figure was Kajar Singh, who had served for two decades in various capacities and was known to British officers as reliable and effective. By mid-1857, after receiving word of widespread revolt in the north, he withdrew from government service. The scale and intent of resistance elsewhere inspired him to lead an anti-British revolt in Khandesh as well.

Kajar Singh established contact with rebel forces moving through the Deccan. Along with Bhima Naik and Mawasia Naik, two other Bhil leaders of regional standing, he began organising coordinated attacks across the interior. Together, they began to move between villages, coordinating the seizure of grain, coin, and arms. The operations were mobile and locally directed. Bhima Naik led several armed forays into the Sindhva Ghat, during which a government officer was attacked. Kajar Singh carried out similar raids deeper inland, targeting settlements aligned with state revenue networks. Efforts were made by Major Evans to open negotiations with Kajar Singh, but these appear to have been unsuccessful.

The British Government, though maintaining a presence in principal stations, grew increasingly concerned by the prospect of coordinated action. In 1858, intelligence reports indicated that Tatya Tope, one of the principal leaders of the uprising, was believed to be advancing toward Khandesh. Though he did not enter the district, his passage through Ahilyanagar (present-day Ahmednagar) and the raids carried out in that region prompted a general strengthening of security. Reinforcements were dispatched to Asirgarh and Burhanpur (Madhya Pradesh), and increased patrols were conducted in vulnerable zones.

The resistance in Khandesh continued into 1859, with Bhagoji Naik, another Bhil leader, launching an attack on Chalisgaon. In the weeks that followed, smaller-scale raids occurred at Pachora and Yawal. These operations, while not coordinated in the manner of earlier actions, reflected the ongoing refusal of local groups to submit to administrative control or territorial absorption.

Parola and its ties to the Rani of Jhansi

The same year also marked the seizure of Parola Fort, which had drawn attention due to its political and familial associations. The fort had come under the management of a relative of Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, whose maternal family, the Tambes, were originally from the area. This connection was treated as politically significant by the authorities of the time.

The occupants were accused of offering support to the wider struggle, and the fort was taken soon after. Reports suggest that several individuals were executed inside the structure, and that deliberate damage was inflicted on its defences. The jagir linked to the fort was absorbed into the state systems in 1860.

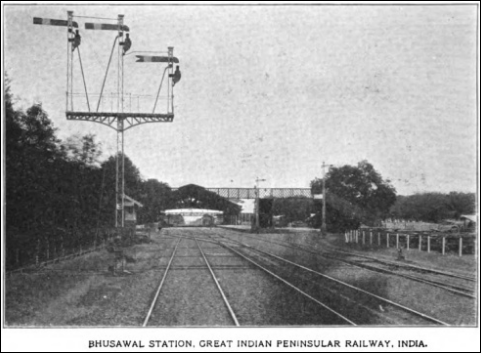

Railways and Bhusawal as One of the Largest Railway Junctions

Amidst this tumultuous time, railway construction began in the Khandesh region as part of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway’s (GIPR) broader expansion across western India. Work commenced in 1852, and by 1865, around 229 km of track crossed what is now Jalgaon district. The line entered the district near Naydongri (in present-day Nashik) and followed the Girna River, passing through major stations including Chalisgaon, Kajgaon, Pachora, Jalgaon, Bhadli, and Bhusawal.

Bhusawal soon became the district’s principal railway hub. From here, the line branched towards Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh) and Nagpur, giving Jalgaon a direct rail link to central and eastern India. Notably, Bhusawal developed into a major railway junction and yard, still among the largest in Asia, with around 243 tracks, handling about 150 trains daily.

The rail network transformed Jalgaon into one of India’s major cotton-growing and trading centres. The line allowed local produce to reach Mumbai’s (then Bombay’s) port efficiently by 1863. British rule also brought railway colonies, complete with workshops, gardens, reading rooms, and a gymkhana. Bhusawal housed one of Asia’s largest steam locomotive sheds, later adapted for diesel and electric engines in the 20th century.

Today, the Bhusawal Division of the Central Railway Zone continues to serve as one of India’s busiest rail systems, connecting Jalgaon’s cotton belt with national markets. The Railway Museum at Bhusawal showcases this legacy through locomotives, carriages, and preserved equipment.

Division of Khandesh District and the Role of Jalgaon

By the early 20th century, both economic centrality and transport connectivity had made Jalgaon a key node in the wider Khandesh region. In 1906, the British administration officially divided the Khandesh district into two parts: West Khandesh (headquartered at Dhule) and East Khandesh, with Jalgaon as its administrative centre.

Following the division, several talukas were reassigned from the original Khandesh district to constitute East Khandesh. These included Amalner, Parola Peta, Bhusawal, Eddlabad Peta, Chalisgaon, Chopda, Erondol, Jalgaon, Jamner, Pachora, Bhadgaon Peta, Raver, and Yawal.

The reorganisation altered district boundaries and administrative jurisdictions. In subsequent years, two additional talukas, Muktainagar and Bodwad, were formed in the Jalgaon district.

Floods & Environmental Strain

In the decades after the formation of East Khandesh, several parts of the district were affected by repeated flooding. One of the earliest major incidents occurred in September 1872, when intense rainfall caused the Girna River and its tributaries to overflow. The flood affected more than 100 villages, with the worst damage reported in Pachora (40 villages), Erandol (36), Chalisgaon (26), and Amalner (12). Homes were destroyed, agricultural land was submerged, and food stocks were lost. A relief committee was formed in response, supported by private donors and the colonial administration. Financial aid was distributed, and temporary support was offered to the affected communities. While limited, this was one of the few instances of organised relief being recorded in the district during the colonial period.

In 1930, flooding again struck the region, this time centred on Pachora, where over 20 villages were submerged. At least ten houses were destroyed, but no direct financial relief was provided. The only official response was a partial reduction in revenue demands, which many considered inadequate.

Further floods followed in 1944, 1946, and 1947, once again affecting tehsils along the Girna. Villages in Bhadgaon and Chalisgaon were particularly impacted. Farmland was inundated, harvests failed, and homes were damaged or swept away. These events caused repeated economic setbacks for farmers, many of whom relied on small plots and had limited means to recover.

Despite the frequency of these floods, historical records indicate that no significant structural measures were implemented during this period to reduce future risk. Relief efforts remained minimal and inconsistent. For most affected communities, recovery depended on local resources and informal support, rather than government intervention.

Post-Independence

Following India’s independence in 1947, the region that is now Jalgaon district was part of the larger Bombay State. This administrative unit included present-day Maharashtra, Gujarat, parts of Karnataka, and various princely states such as Baroda. On 1 November 1956, the States Reorganisation Act redrew internal boundaries across India, aligning them with linguistic demographics.

As a result, on 1 May 1960, the Bombay State was divided into the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. The newly formed state of Maharashtra was created by merging the Marathi-speaking areas of the Bombay State with select districts from the Central Provinces and Berar, Hyderabad State, and some princely territories.

In this reorganisation, the region previously known as East Khandesh was redefined, and the present-day Jalgaon district was formally established. Jalgaon district is presently divided into fifteen talukas: Jalgaon, Chalisgaon, Bhusawal, Jamner, Chopda, Raver, Pachora, Amalner, Yawal, Parola, Dharangaon, Erandol, Muktainagar, Bhadgaon, and Bodwad.

Sources

Alexander Kyd Nairne. 1896. Gazetteer Of The Bombay Presidency. Vol. I, Part II. The Government Central Press, Mumbai.

Census of India. 2001. District Census Handbook. Jalgaon.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

E Rail. Bhusaval Railway Division Information.https://erail.in/info/central-railway-bhusav…

H. S. Thosar. 1990 “The Abhiras in Indian History.” Vol. 51, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.http://www.jstor.org/stable/44148188

Henry Cousens. 1913. Mediaeval Temples Of The Dakhan. Vol.27, p. 24. Cosmo Publication, New Delhi, India.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

IRCFA. Indian Railways History: 1900 - 1946.https://irfca.org/faq/faq-history3.html

James M Campbell. 1880. Gazetteer Of Bombay Presidency. Vol. XII. Khandesh. Government Central Press, Mumbai.

Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri. 1958. A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar. p. 482. Oxford University Press, India.

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1962. Jalgaon District.Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Mukhyapurush. n.d. Patanadevi.comhttps://patnadevi.com/

PTI. 2023. “Maha: ASI gets teak from Melghat for renovation, conservation of Jalgaon’s Changdev Temple.” The Print.https://theprint.in/india/maha-asi-gets-teak…

R.S. Pappu. 2004. “Contribution of Deccan College to Stone Age Research.” Vol. 64 no. 65,Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute.http://www.jstor.org/stable/42930631

Robert G. Bednarik. 1993. About Palaeolithic Ostrich Eggshell in India. IFRAO Bulletin.https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Engraved…

S. M. Katre and P. K. Gode, eds. 1947. New Indian Antiquary. Vol. IX, Nos. 1–3. Karnatak Publishing House, Mumbai.

Sudama Misra. 1973. Janapada State in Ancient India. Bhāratīya Vidya Prakasana, India

Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya (1974). Some Early Dynasties of South India. p. 129. Motilal Banarsidass, India.

Susan E. Alcock, ed. 2001. Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom.

Tour My India. Parola Fort, Jalgaon. Tour My India.https://www.tourmyindia.com/states/maharasht…

Upinder Singh. 2008. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education, India.

V. R. Deoras. 1958. “The Rivers and Mountains of Maharashtra.” Vol. XXI,Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44145192.pdf

V.D Mahajan. 1953. Mughal Rule In India. p.99. S. Chand & Co., New Delhi, India.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

Vincent Arthur Smith. 1919. The Oxford history of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911. The Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.