Contents

JALNA

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Jalna’s architecture reflects a layered blend of Yadava, Mughal, Maratha, and colonial influences. Stepwells like the Pokharni and Kavandi baravs reveal deep knowledge of water engineering, with precise stone joinery and structural innovations dating back to the 12th–14th centuries. Mandirs such as Kholeshwar, Amruteshwar, and Shri Chakradhar Swami Mandir showcase Hemadpanthi architecture, while the wooden Anandi Swami Mandir stands out for its rare use of carved teak. The Kali Masjid and adjoining Hamam Khana display Indo-Islamic and Mughal-era design, while Christ Church reflects colonial-era Gothic and Indo-Saracenic styles. Together, these structures capture Jalna’s diverse architectural legacy, shaped by dynastic rule, regional craftsmanship, and religious traditions.

Pokharni Step Well (Barav)

The Pokharni barav (stepwell) is located in Ambad taluka and dates back to the Yadava period (circa 12th–14th century), with later renovations carried out by Ahilyabai Holkar. Stepwells were more than just water reservoirs—they were architectural marvels that combined utility, spirituality, and artistry, shaping subterranean architecture across western India from the 7th to the 19th century. Measuring 54 meters in both east-west and north-south directions, the Pokharni barav reaches a depth of 48 meters. A small mandap and shrine are located on the western side, and entry is possible from all four directions.

Unlike deeper wells, the Pokharni barav is relatively shallow and narrow, with construction focused at the base. This design has earned it the local name ‘Pokharani’. The well exemplifies the broader tradition of Jalna’s stepwells, many of which were built during the Yadava and Mughal periods as community water sources.

The structure follows an intelligent engineering design. Walls were constructed to resist groundwater pressure using reinforced stone joints, lime mortar, and carved notches. These allowed water seepage to be regulated and prevented collapse. Cornerstones were set at right angles for added strength, and upper stones were carefully layered using interlocking methods such as utangal, including the use of melted lead or copper to fill gaps.

This meticulous craftsmanship and knowledge of material behaviour under pressure allowed the Pokharni Stepwell and many others in the region to survive for centuries, even resisting minor seismic activity.

Kholeshwar Mandir

Kholeshwar Mandir is an ancient Mandir situated about 3 km from the renowned Rajur Ganpati Mandir in Bhokardan taluka. Constructed in the 13th century, it follows the Hemadpanthi architectural style, characterised by precise stone joinery without the use of cement or mortar. Though the Mandir’s pinnacle is missing, its stone-carved statues and structural elements remain remarkably intact.

The Mandir houses a shivling in the garbhagriha (sanctum), and its sabhamandap (pillared hall) stands with minimal damage, offering insight into the skilled stonework of the era. The site is surrounded by natural beauty, located close to a quiet lake and the Purna River. Its remote setting and lack of crowds contribute to the peaceful, meditative atmosphere.

The upper portions of the Mandir feature intricate carvings and layered stone arrangements that reflect both artistry and engineering acumen. Even from the side elevations, the Mandir’s form and decorative detailing can still be appreciated.

Shri Chakradhar Swami Mahanubhav Mandir

The Shri Chakradhar Swami Mahanubhav Mandir is located in the Sashte Pimpalgaon area of Ambad. Formerly known as the Somnath Mandir, this Mandir has a history dating back nearly 800 years. It was built during the Yadava dynasty’s rule (circa 12th–14th century), when Devagiri (now Daulatabad) was the capital.

The Mandir is an important example of Hemadpanthi architecture, known for its use of locally available black basalt stone and lime, laid without mortar. Its strong lines, minimal ornamentation, and enduring stonework reflect the technical expertise of the time.

Today, the Mandir functions as a spiritual hub for the Mahanubhav sect. It houses many sants who live ascetically, gathering alms in nearby villages. The site remains an active religious space and is regarded as a place of spiritual importance.

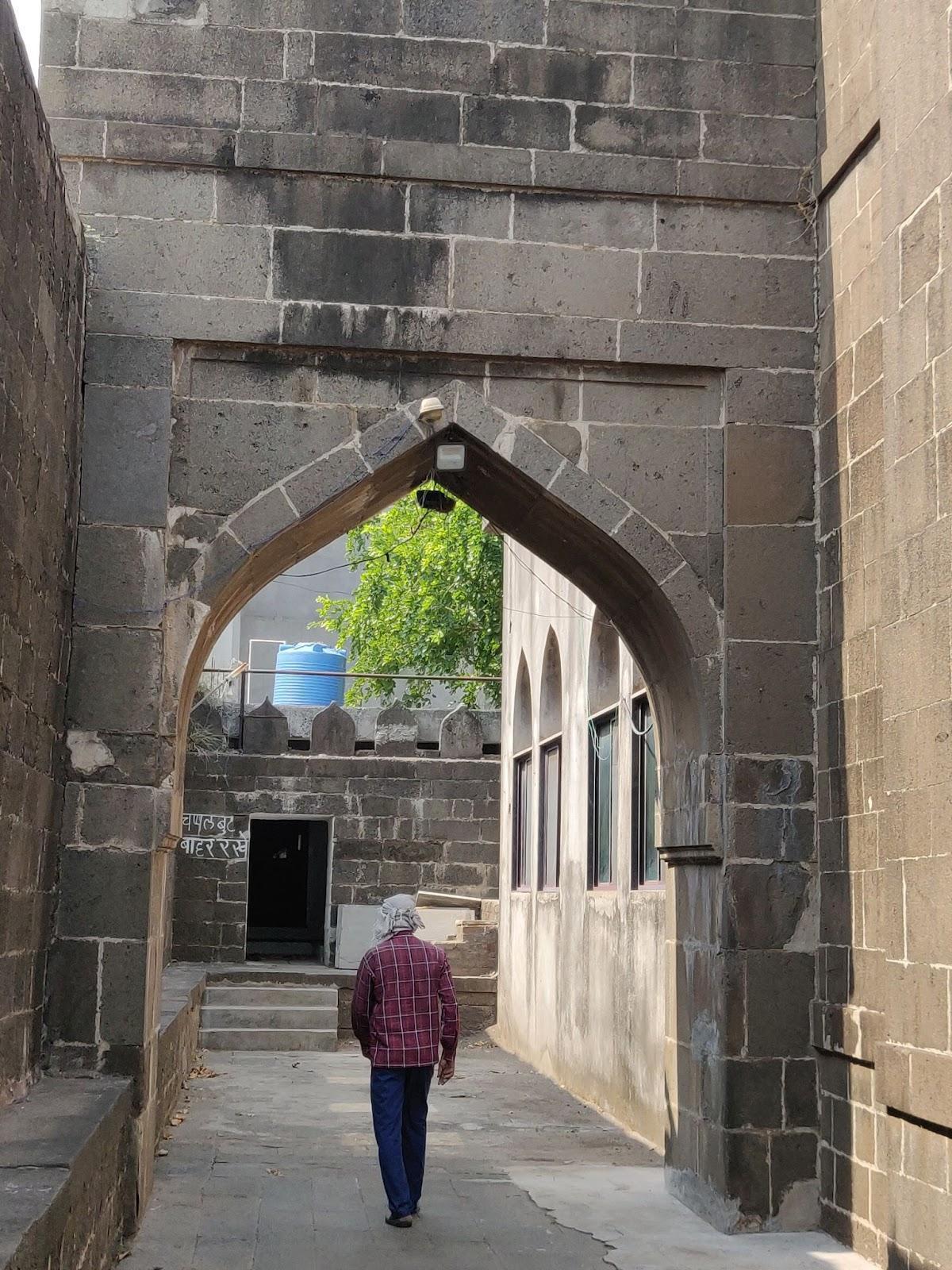

Kali Masjid

Kali Masjid is one of the oldest and most architecturally significant mosques in Jalna, dating back to around 1578 CE. It was commissioned by Jamshed, a Mughal-era subhedar, and constructed using black stone, earning it the name Kali (black) Masjid. The masjid served as a spiritual and logistical centre for traders and Sufi saints travelling through the region.

Located in Old Jalna, the mosque sits within a rectangular walled compound, enclosed on three sides, with an arcade of arches at the front. The structure features finely carved black stone blocks, pierced jali screens, and Mughal-style domes with floral motifs. Its principal dome is crowned and based with stone-carved lotus leaves and topped with a spire, exemplifying Indo-Islamic design. Octagonal columns support six small domes, while the main prayer hall is adorned with Arabic and Persian inscriptions.

Inside the compound is a paved courtyard with a large quadrangular sarai (cistern) connected to Moti Talab by an underground water system. This tank, once filled with fresh water, was a vital part of the masjid’s daily rituals. On the northeast side of the masjid lie five unmarked graves.

Opposite the masjid stands the Hamam Khana (bathhouse), constructed five years after the masjid and reflecting similar Mughal-era finesse. The Hamam Khana includes carved stone walls, fluted domes, and corner finials. Inside are steam rooms ventilated by four large brick-and-limestone exhausts. Persian inscriptions above the entrance door mark its historical legacy.

Hot and cold water were both made available here, with hot water stored at higher elevations to allow gravity and thermal flow to warm the cold water. One of the Hamam rooms today serves as an office for the Waqf Board. Though the structure is in a state of decay, it remains a rare example of functional Mughal public architecture.

Kavandi Barav

Located in the older parts of Ambad taluka, the Kavandi Barav (stepwell) is a remarkable example of historical water architecture, measuring approximately 23 meters east–west and 19 meters north–south. Constructed in three phases, the Kavandi barav features its main entrance on the eastern side. After descending ten steps, one reaches a narrowing central staircase (sopan) that deepens into a kund-like form. The stepwell also houses two Devli-style structures likely meant for placing murtis or diyas. It is believed that the site was later renovated under the patronage of Ahilyabai Holkar.

Within the stepwell, a 15-by-3-meter mandap is built into the southern wall. This rectangular pillared hall, supported by sixteen columns and enclosed on three sides, includes a small shrine. While only one entrance remains today, historical accounts suggest an additional entry point once connected directly to the mandap.

The stepwell’s pillars are adorned with intricate carvings of animals and floral motifs, reflecting the craftsmanship of the period. These finely detailed decorations not only enhanced the structure’s aesthetic appeal but also served as symbols of reverence and cultural identity.

Despite its beauty and significance, the Kavandi Stepwell today faces neglect. Locals often dump garbage into it, filling water holes with plastic waste. Though the Archaeological Survey of India has begun clean-up efforts, community involvement remains limited. Sustained conservation efforts are urgently needed to preserve this unique architectural and ecological heritage.

Amruteshwar Mandir

The Amruteshwar Mandir, located in the heart of old Jalna city, is a significant example of Hemadpanthi architecture. Built during the reign of Ahilyabai Holkar (1767–1795), the site features two stone mandirs facing each other, one dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv and the other to Bhagwan Hanuman. A Nandi is placed in between, facing the Shiv Mandir. The entire complex is constructed from finely cut basalt blocks, stacked without mortar and secured with lime.

The Shiv Mandir’s ceiling is especially striking, composed of interlocking stones topped with large basalt slabs to ensure balance and strength. In contrast, the Hanuman Mandir features a circular stone arrangement with a finely carved central keystone. These construction methods reflect both technical precision and aesthetic care. The site becomes especially vibrant during the month of Shravan, when devotees gather on Mondays for collective worship, bhandara, and festive celebrations.

Adjacent to the mandir stands a large barav, believed to have been built around 220–250 years ago during the rule of Yashwantrao Holkar. Constructed in the same Hemadpanthi style, this 30–35 foot deep structure once provided water for pilgrims and the local community, and is still admired for its architectural depth and the sweetness of its water.

Anandi Swami Mandir

The Anandi Swami Mandir, located in the older part of Jalna city, is a rare example of a wooden mandir structure in the state. Built around 250–300 years ago, it is renowned for its elaborate teakwood construction and detailed carvings. The Mandir is two storeys tall, supported by a stone base and brick walls, while the interiors, including columns, beams, and ceilings, are entirely made of finely carved teakwood. Mahadji Shinde, a prominent Maratha noble and devotee of Anandi Swami, is believed to have funded its construction.

Anandi Swami Mandir features intricately carved wooden ceilings on both floors. Large beams connect the columns, while long wooden planks span the structure to form walkways and overhead platforms. At the centre of the Mandir is a square, open area reserved for meditation and quiet reflection, underscoring the spiritual purpose of the space. The Mandir’s wooden craftsmanship, combined with its preservation over centuries, makes it architecturally and historically significant not only in Jalna but across the state.

Christ Church

Christ Church in Jalna showcases a blend of Gothic and Indo-Saracenic architectural styles. Its pointed arches, sloping roof, and decorative detailing reflect a fusion of European and Indian design influences. The church remains a significant landmark of colonial-era architecture in the region.

Residential Architecture

In Jalna, each home carries the imprint of the era it was built in. Jalna’s architectural heritage includes numerous wadas dating back to the Nizam Shahi, Bahamani, and Peshwa eras. These structures typically feature a combination of teak wood, stone, and brick construction. Malwad houses in the region, though simpler in scale, follow similar principles of climate-responsive design and material economy. Across centuries, these homes have adapted to shifting resources; newer constructions now use neem wood instead of teak, introduce cement slabs, and respond to changing weather patterns. Yet, in both city and village, time continues to shape and reshape the idea of home.

An 18th Century Wada at Jalna City

In one of the narrow lanes off Kacheri Road in Jalna City stands a wada estimated by locals to be approximately 250-300 years old. The Wada is a three-storey structure that has a very interesting design and layout.

The Wada houses many motifs which locals say are common to the local architectural style of the region. Notably, many unique spaces like underground rooms, a dedicated devghar (prayer space), and a still-functional underground water storage system with a capacity of around 1000 litres can be found here.

The ground floor is made of local black basalt-dressed coursed masonry, internally finished with paint and externally kept in its natural finish. The upper floors are made of brickwork and finished with a metal sheet roofing on top.

Many elements in the Wada show that local climate was considered when building the structure. With Jalna being a low rainfall region, the house features minimal plinth height and roof slope. The visual character of the structure is distinctly rustic, as construction materials are largely preserved in their natural form.

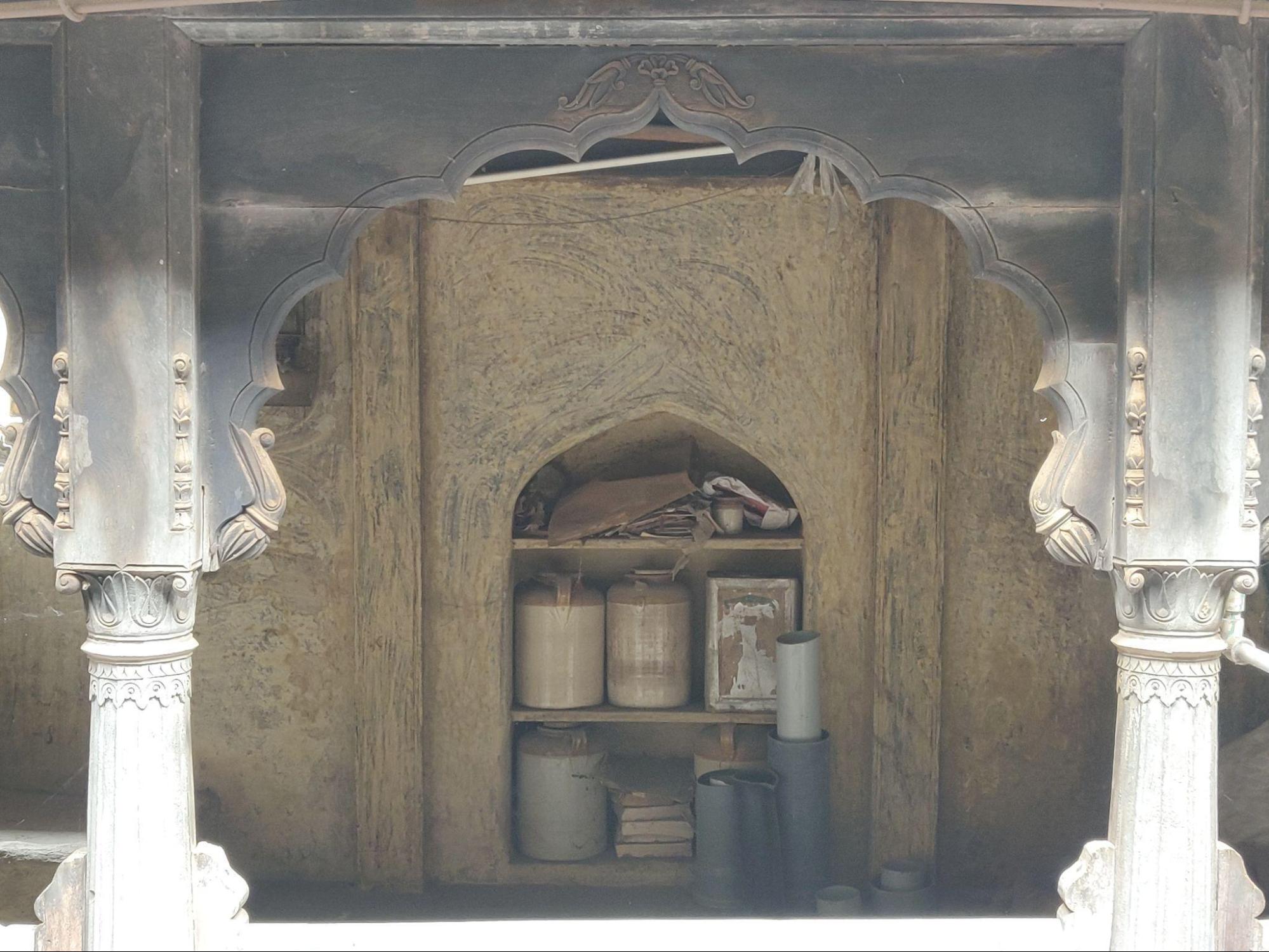

The doors and windows of the house present notable architectural features.

The entrance door displays detailed woodwork that creates a distinctive street presence. The top section, known as 'mandap,' features intricate carvings with traditional symbols. Supporting columns on either side enhance the visual composition. Interior doorways utilise wooden double doors with characteristic design elements.

The windows exhibit a hierarchy of design elements. The first-floor windows feature decorative brickwork arches and ornamental motifs, while ground-floor windows employ simpler designs with metal grills. Window panels consist of wooden plank double doors. Responding to the hot, dry climate, some windows incorporate a stepped interior design that reduces direct sunlight while maximising indirect light.

The house has some unique stepwise windows in some places. The windows feature strategic structural arrangements that prevent direct sightlines from outside or neighbouring buildings into the interior spaces.

The layout of the wada is very interesting. The interiors have two distinct sections, one of which has been better preserved. All rooms open onto courtyards, with balconies on the upper floors and verandahs at ground level. These open spaces serve as communal areas for residents. The decorative aspects of each space are noteworthy.

The main courtyard functions as a semi-private space for residents and features notable architectural details, particularly at the corners. The stone flooring showcases traditional paving patterns that have endured for centuries. The stonework displays an interlocking system where stones are arranged so that the middle stone must be removed first, a technique that enhances structural stability.

The second courtyard is dedicated to bathing and kitchen-related activities. This more private space, primarily used for women’s activities, is smaller than the first courtyard and includes an in-situ water storage tank and a stone “chaurang” (small seating area).

The bathing area features a stone-carved seat, an example of functional elements that also display craftsmanship. The water storage system remains a notable feature of the wada's design, with underground chambers that have remarkably remained functional for centuries.

The walls of the structure are impressively thick, approximately 3 feet wide, and constructed using large black stones.

The water storage system remains a notable feature of the wada's design.

The wada features an enclosed staircase system connecting different levels. The staircase entry features a low doorway, a common element in historical architecture that served both practical and defensive purposes.

The upper levels provide views of the courtyards below, demonstrating how these central voids served as both light wells and ventilation shafts. The spatial arrangement reveals how rooms were organised around these central open spaces. The railings are a blend of decorative metal grills and a wooden top rail, reflecting the craftsmanship typical of transitional domestic architecture.

The third floor shows significant deterioration, with structural elements exposed to the elements, though it provides a valuable perspective of both the wada's internal organisation and its relationship to surrounding buildings.

The exterior of the wada displays characteristic elements of regional architecture, with minimal openings for security and privacy. The building responds to the street alignment and adjacent structures in a way that was typical for urban dwellings of this period. The exterior façade of the house showcases a distinct material contrast between the lower and upper levels. The ground level is constructed using black stone masonry, while the upper level is built with exposed brickwork.

The rear portion of the property includes a backyard area and the devghar (prayer space), which occupies a significant position within the household layout, reflecting the importance of religious practice in daily life. It also features an external underground stone water storage system and an open area designated for keeping cows.

A 19th Century Wada

Located on a main street in Jalna is a 19th-century wada estimated to be 150-200 years old. Due to road widening, the house now sits adjacent to the footpath, with a verandah serving as a transitional space between the house and street.

This wada features more extensive use of wood. The front facade is distinguished by wooden pillars with intricate designs, while the rear portions follow older patterns with stone foundations and brick upper structures. Notably, the brick sections include decorative elements and an inscription of the establishment date.

What makes this wada particularly significant is the preservation of original furnishings and fixtures, including beds, mirrors, and furniture, offering a complete picture of historical domestic life.

The construction combines several materials in a pattern that evolved from earlier traditions. Common walls and the back wall of the ground floor are made of stone, while upper floors feature brick construction finished with lime plaster. Interiors are painted with oil paint. The structural framework consists of solid wood columns and beams, with metal sheet roofing.

The colour scheme employs cool tones, primarily green with blue accents for highlighting architectural elements.

The wada features distinctive door and window treatments that demonstrate the evolution of craftsmanship.

The doors of the wadas are made of wood, typically consisting of an outer door and a double-shuttered inner door. The inner doors are often intricately carved, reflecting the high level of craftsmanship invested even in functional elements of the home.

The windows vary between the front and back facades, reflecting both functional needs and public presentation. The rear windows differ significantly from those on the street-facing facade. They are simpler in design, with an outer arch and metal grills fitted into a wooden framework.

The front windows, by contrast, display greater ornamental attention. This elaborate detailing reflects their importance in the public presentation of the household.

The middle section of the wada serves as the main living space, designed to be a central gathering area with a focus on light, spatial quality, and the use of vibrant colours to highlight its architectural features.

Malwad Houses of Jalna

In the rural areas of Jalna, traditional dwellings known as "Malwad" houses represent a distinctive architectural approach. These structures feature carved square stones placed beneath supporting pillars. This construction method is standard throughout both urban and rural regions of Jalna. Malwad houses typically maintain structural integrity for approximately 125-150 years.

The main entrance door is wooden, double-shuttered with a panel design. Above it, there is a clerestory window with vertical railings and a wooden shutter. The inner door in the courtyard is also wooden and double-shuttered with panels, but appears more worn out and is a different colour than the main door.

The main entrance opens into a narrow courtyard, with stone tiling that adds texture and warmth to the passage. The roof of this passage is made of wood, featuring an exposed wooden framework. The wooden roof has some intricate carvings, enhancing the aesthetic appeal of the space.

The courtyard serves as the central open space around which all rooms in the house are organised. It functions as a shared area for daily activities, while also bringing in light and ventilation to the interior spaces. The rooms open directly into the courtyard, creating a strong functional connection across different parts of the house. On the upper storeys, on the inner side of the courtyard, are railings made of a wooden framework and a top rail, with decorative metal grills that add both safety and ornamentation.

Interestingly, unlike the older Malwad houses that predominantly used teak wood and followed time-tested methods, in the rural parts of Jalna, especially in the Ambad and Ghansawangi talukas. There is a noticeable trend where people have begun modernising Malwad houses in response to changing climatic conditions and available resources. While older structures still exist in some areas, the newer houses being constructed adopt updated techniques. They retain the traditional Malwad form but now use neem wood instead of teak due to its lower cost and higher availability. Additionally, slabs are placed on the wooden floor, and a plastic cover is placed between the wood and cement to prevent their mixture. This adjustment is largely in response to the rising heat in the region. This helps ensure that the house remains warm during winters and cool during summers.

In this newly constructed Malwad house, the entrances feature two side-by-side wooden double-shuttered doors, probably leading to separate homes within the same compound. Made from polished neem wood, the doors have simple decorative carvings and are set within matching polished neem wood frames. Above each door, clerestory windows with black metal grills are integrated seamlessly into the frame to allow light and ventilation. The windows in the house also include black metal grills, with sliding glass panels fitted into the frames. The wooden roof structure, with its exposed rafters, carries forward the traditional architectural element while adapting to new material preferences.

The terrace and interiors of the newly built Malwad house retain an unfinished cement finish, reflecting a raw and functional aesthetic. Inside the house, the exposed wooden framework, likely neem wood, is visible on the walls, tying the interior design closely to the house's architectural lineage.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.