Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Associations with the Ramayan

- Satavahana Period and Urban Settlement at Bhokardan

- Rohillagadh

- Later Dynasties & Political Shifts

- Kholeshwar Mandir

- Pokharni Stepwell

- Medieval Period

- Bahmani to Ahmadnagar Sultanate

- Kali Masjid & the Nizam Shahis

- Jalna Sarai and Trade Routes

- Mughal Rule & the Jagir of Jalna

- Jaffrabad

- Samarth Ramdas

- Nizams of Hyderabad

- Jalna Fort and Asaf Jah I

- Maratha Presence in the Region

- Ahilyabai Holkar and the Matsyodari Mandir in Ambad

- Conflict and the Battle of Assaye (1803)

- The British–Nizam Alliance and Subsidiary Rule

- First War of Independence, 1857

- Cotton and Industrial Growth in the Early 20th Century

- Post Independence

- Sources

JALNA

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Jalna district, located in the Marathwada region of central Maharashtra, was officially established on 1 May 1981 after being carved out of the Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar (then Aurangabad) and Parbhani districts. Although it gained administrative status in the late 20th century, the region has a much older history. Local traditions link parts of present-day Jalna to episodes from the Ramayan, including the travels of Bhagwan Ram.

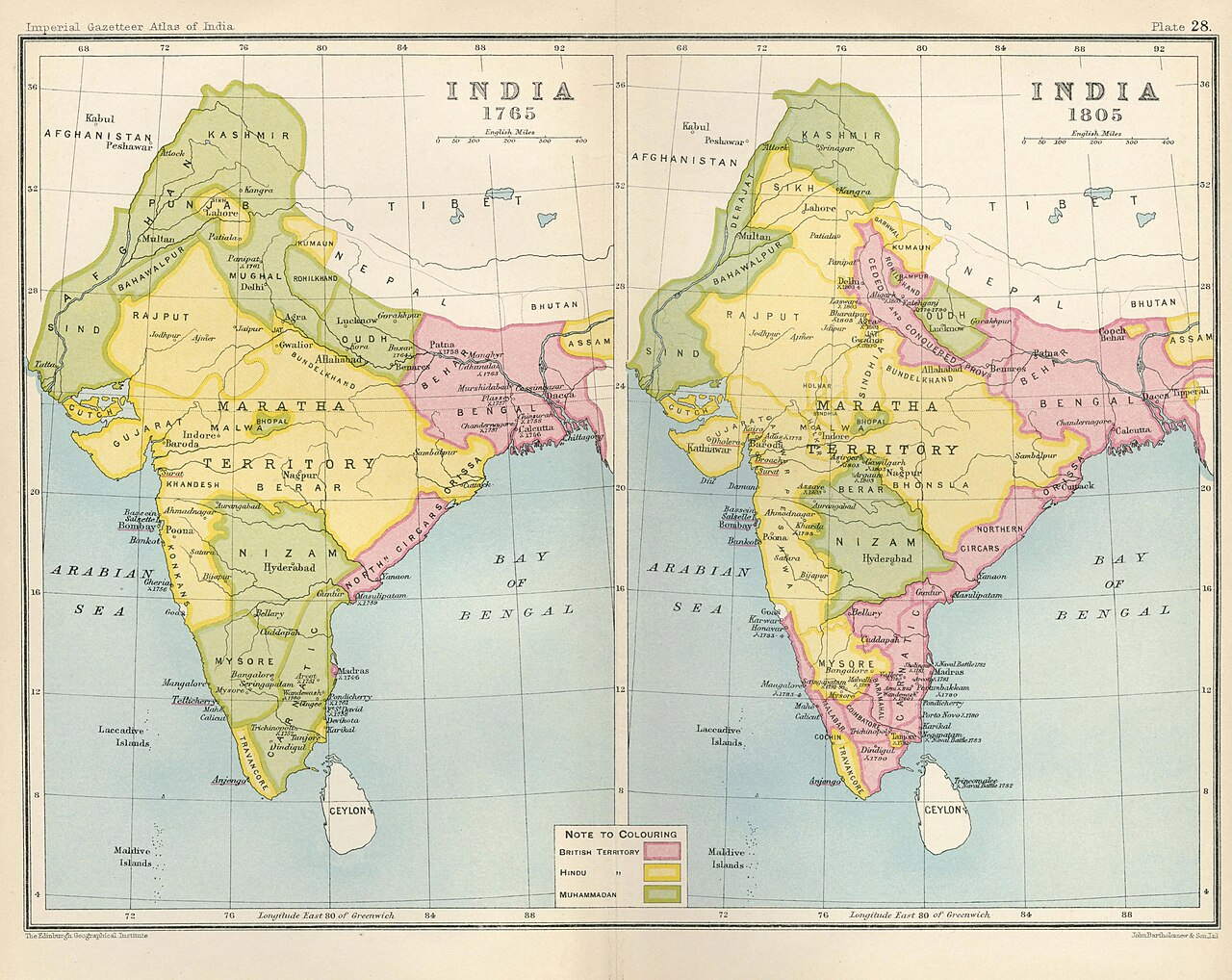

Over centuries, Jalna’s central location in the Deccan placed it along important inland trade routes linking western India with the interior. Interestingly, towns like Bhokardan in the district were major trading centres in the early days where agricultural goods, textiles, and metalware were exchanged and moved toward larger markets. The area came under the control of several major powers over time. It likely formed part of the Maurya and Satavahana domains in the early historic period, followed by incorporation into the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire during the medieval era. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it was part of the Maratha Empire, before being absorbed into the Nizam's territory and eventually British rule. What many might not know is that during the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), the village of Assai in present-day Jalna district became the site of a notable military engagement.

Etymology

The origin of the name Jalna is often linked to the town’s artisanal past, particularly its association with weaving. It is believed that the area was once known as Janakpur. Over time, as the town grew into a local centre of craft and trade, its identity began to reflect the occupations that shaped its economy.

According to local tradition, a wealthy Muslim merchant, known for his skill in weaving, settled in the town during the medieval period and contributed significantly to its economic growth. As weaving became a defining feature of the settlement, the term Jalana came to be closely associated with the place. Over generations, this association is said to have influenced the transformation of the name, from Janakpur to Jalana, and eventually to Jalna.

Ancient Period

The region now comprising Jalna district has historically been governed by several political and cultural powers that shaped the Deccan plateau. While little is known about the ancient history of Jalna, archaeological evidence, traditions, and proximity to major early trade centres allow for a broad reconstruction of its early history. These developments are best understood in the context of Marathwada and the central Deccan, with which Jalna has long shared administrative and cultural ties.

Associations with the Ramayan

One of the earliest cultural traditions associated with the Jalna region is connected to events from the Ramayan, specifically to the path believed to have been taken by Bhagwan Ram during his exile. The Nangartas Mandir, located in Mantha taluka, is locally identified as the 148th stop along what is referred to as the Ram Gaman Marg.

According to oral tradition in the region, when Bhagwan Ram passed through this area during his exile, he instructed Lakshman to teach ploughing to the local inhabitants, who were said to be unfamiliar with settled agriculture. Interestingly, the Marathi word for plough is nangar and is believed to have given the site its name, Nangartas.

Satavahana Period and Urban Settlement at Bhokardan

In the 3rd century BCE, the Maurya Empire is believed to have exercised control over much of the Deccan, which would have included the area now forming the Jalna district. Following their decline, the Satavahanas rose to prominence as the primary ruling dynasty across the Deccan. They ruled from approximately the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE, with their capital at Pratishthana (Paithan).

Notably, following the decline of Mauryan authority, the Satavahanas emerged as the dominant political power in the region. They ruled from approximately the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE, with their capital at Pratishthana (modern Paithan).

Archaeological evidence, including artefacts and structural remains attributed to the Satavahana period, suggests that portions of the present-day Jalna district were incorporated into the dynasty’s administrative or cultural domain. Among the sites of historical significance, Bhokardan is notable for its development into a prominent urban centre and trading settlement during this time. The town is traditionally associated with a ruler named Bhogvardhan (also referred to as Bhagdnath), of whom not much is known. Interestingly, Bhokardan is believed to have prospered under Satavahana rule and is referenced in local traditions as having rivalled other contemporary urban centres such as Paithan and Ter.

Excavations carried out in 1973–74 by Nagpur University and Marathwada University revealed a large early historic settlement at Bhokardan, spread across two high mounds. The material recovered included red-slipped pottery, black-on-red ware, Satavahana coins, terracotta figurines, beads, and ivory objects. These artefacts indicate continuous occupation of the site from the pre-Satavahana through to the post-Satavahana periods and suggest a certain degree of economic and cultural prosperity.

One of the most notable finds from Bhokardan is an ivory figurine of a female figure, dated to the Satavahana period. Fascinatingly, a similar ivory figurine was discovered at Pompeii, Italy, which was buried during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. The resemblance between the two objects has led to speculation about possible long-distance trade links between Bhokhardan and the Mediterranean world. The Bhokardan specimen is currently housed in the museum of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University in Sambhaji Nagar district.

The town’s location also underscores its historical relevance. According to historian Upinder Singh (2016), Bhokardan was situated on a trade route that connected Ujjayini (modern Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh) with Paithan (in present-day Sambhaji Nagar district), which was the capital of the Satavahanas. Following the decline of the Satavahana dynasty, Bhokardan appears to have lost its status as a major trade hub.

Rohillagadh

Another site in present-day Jalna district associated with the Satavahana period is Rohillagadh, where a group of rock-cut caves have been discovered. These caves are believed to have been constructed under the patronage of the Satavahana rulers. The location of the caves at Rohillagadh, along with its architectural features, indicates that this area may have held strategic importance, possibly functioning as a defensive outpost or a religious site within the broader Satavahana administrative framework.

Later Dynasties & Political Shifts

Following the decline of the Satavahanas in the 3rd century CE, the Vakatakas emerged as a major political power in the Deccan. Their influence likely extended into parts of the present-day Jalna district, as suggested by archaeological remains in the region.

One such site is Latifpur, located approximately 16 km south of Bhokardan, on the right bank of the Girija River. At the centre of the village lies a prominent 15-meter-high mound, locally known as Garhi. Although modern settlement has encroached upon it from all sides, the site has yielded significant evidence of early historic occupation. According to Chouhan et al. (2015), archaeological finds from Latifpur include potsherds attributed to the early Satavahana and Vakataka periods, including examples of black and red ware as well as pottery with jet black, yellowish-brown, and brown slips.

Later, the region likely came under the sway of the Chalukyas of Badami (6th to 8th century CE). While no inscriptions from this period have been documented within Jalna itself, their expansion into Asmaka and surrounding areas makes it plausible that Jalna was included within their sphere.

The Rashtrakutas, who ruled from the mid-8th to 10th centuries CE, succeeded the Chalukyas and left a major imprint on the region’s religious landscape. Their influence is most visible at Ellora, in present-day Sambhaji Nagar district, but their architectural patronage and administrative networks likely extended into Jalna.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries, the region appears to have come under the control of the Western Chalukyas (Chalukyas of Kalyani), followed by the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri. During the Yadava period (12th–14th centuries CE), a number of religious and civic structures were constructed across the region, some of which remain extant.

Kholeshwar Mandir

The Kholeshwar Mandir, located in Bhokardan Taluka, is a notable example of regional temple architecture from the Yadava period. Built in the 13th century CE, the Mandir follows the Hemadpanthi style, an architectural tradition named after Hemadri (or Hemadpant), a minister in the court of the Yadava rulers. This style is characterised by the use of large, precisely cut stone blocks laid without mortar, as well as star-shaped plans and minimal ornamentation.

The Mandir houses a Shivling in its sanctum and is situated near the banks of the Purna River and a nearby lake, lending the site a scenic and serene setting. Although the original shikhara (tower) no longer survives, the main structure and stone carvings remain well preserved.

Pokharni Stepwell

Located in Ambad Taluka, the Pokharni Stepwell (locally known as Barav) is another important civic-religious structure dating to the Yadava period. The stepwell measures approximately 54 metres in length and width and descends to a depth of 48 metres. It is accessible from all four sides and features a mandapa and a small shrine on its western side. The structure’s distinctive narrow profile and weight distribution, heavier at the base, have led to its local name, Pokharani, distinguishing it from other stepwells in the region.

The stepwell was later restored by Rani Ahilyabai Holkar in the 18th century, perhaps pointing to its continued significance across centuries.

Medieval Period

In 1294, Alauddin Khilji, nephew of Sultan Jalaluddin Firoz-Shah Khilji, led an expedition into the Deccan, targeting Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad). This marked the beginning of a series of northern incursions into the region, with further campaigns in 1306, 1308, and 1310. At the time, the area was ruled by the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri.

These military campaigns, particularly those led by Malik Kafur, the general of Alauddin Khilji, signalled a shift in power dynamics in the Deccan. The region was not a unified political entity but a mosaic of semi-autonomous territories. Through appointed viceroys, the Delhi Sultanate maintained intermittent control over parts of the Deccan, including areas around present-day Jalna, for nearly two centuries.

Bahmani to Ahmadnagar Sultanate

By the mid-14th century, the Sultanate’s influence began to wane. In 1347, the Bahmani Sultanate declared independence from Delhi, establishing control over a significant part of the Deccan. Although their authority in the Jalna region appears to have been limited, possibly lasting only a few decades, the Bahmani rulers divided the Deccan into eight provinces in 1480, including areas that now fall within Maharashtra. Jalna likely became part of one of these provinces then.

The Bahmani kingdom eventually fragmented into five successor states: the Adil Shahis of Bijapur, Qutb Shahis of Golconda, Imad Shahis of Berar, Barid Shahis of Bidar, and Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar. Control of the Jalna region eventually passed to the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, following ongoing conflicts between these states.

Kali Masjid & the Nizam Shahis

Under the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, several architectural and civic structures were established in Jalna. In the 16th century, a local governor, Jamshid Khan, is credited with constructing the Kali Masjid, a mosque built entirely from locally quarried black basalt stone, giving the structure its name (Kali meaning "black").

The mosque stands in the heart of old Jalna city. Stone for its construction was sourced from the western side of the site, where a large pond known as Moti Talab was later formed. This pond not only supplied water for construction but also became a local landmark.

Jalna Sarai and Trade Routes

Opposite the Kali Masjid lies the Jalna Sarai, a rest house for travelers and traders. It features a large square courtyard surrounded by arcaded chambers, reflecting its historical role in facilitating travel and trade through the Deccan.

The region sat along the Burhanpur–Surat trade route, which historically linked Gujarat’s commercial centres to the southern Deccan. Jalna likely served as a waypoint for merchants heading north through Nashik to Surat, highlighting the town’s strategic and economic importance during the medieval period.

Mughal Rule & the Jagir of Jalna

In 1596, Chand Bibi, the regent of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, was forced to cede Jalna to the Mughals following mounting military pressure. Under the Mughals, the town was classified as a tehsil, though its frontier location gave it added strategic weight.

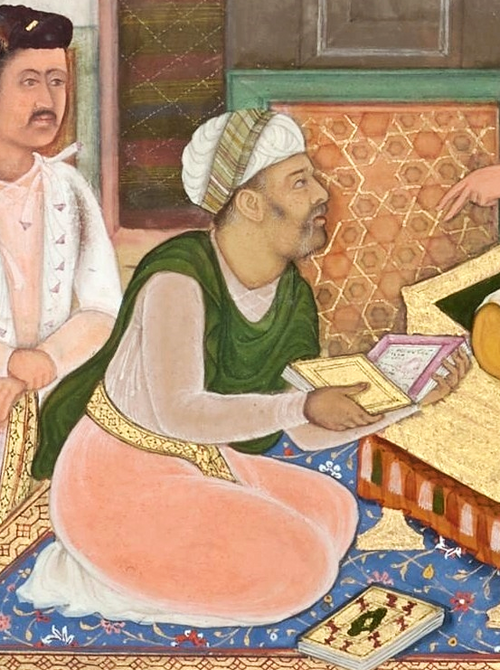

According to the Ain-i-Akbari, compiled by Abul Fazl during the reign of Akbar, Jalna marked the southern boundary of the Subah of Khandesh. Interestingly, the document notes that Jalna was held as a jagir by Abul Fazl himself.

Jaffrabad

Another significant settlement linked to the Mughal-era jagirdari system is Jaffrabad, now a taluka in Jalna district. Located at the confluence of the Purna and Kirna rivers, the town was granted as a jagir (land revenue assignment) to Jafar Khan, a Mughal military officer under Emperor Aurangzeb, along with 115 surrounding villages.

During this period, the town was fortified, underscoring its administrative and strategic importance. Although much of the outer wall has deteriorated over time, a stone gaddi (raised platform) remains intact within the fort precinct. Jaffrabad was also noted for its baniya (merchant) shops, suggesting it served both as a military post and a modest commercial centre during the Mughal period.

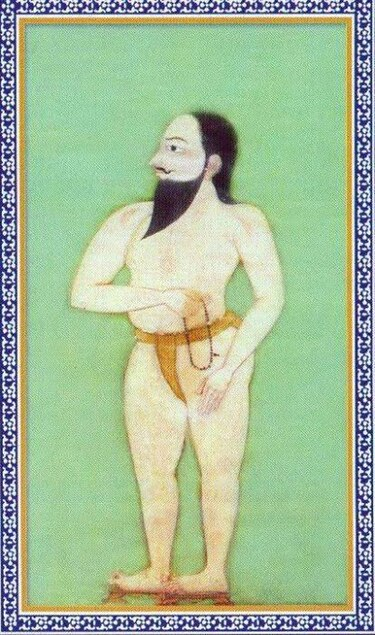

Samarth Ramdas

Jalna district is also closely associated with Samarth Ramdas (1608–1681), a prominent Hindu sant, philosopher, poet, and spiritual reformer of the Bhakti movement. He was born in the village of Jamb, located in present-day Jalna district, into a Marathi Deshastha Brahmin family.

According to tradition, Ramdas’s spiritual path began at an early age. At the age of twelve, during a wedding ceremony in the nearby village of Asangaon, the priest's recitation of the word “Saavdhan” (“Beware!”) is said to have deeply affected him. This moment prompted him to abandon the ceremony and begin a life devoted to spiritual pursuit.

In the years that followed, Ramdas left his home in Taakli and undertook an extensive pilgrimage across the Indian subcontinent, which lasted twelve years. During his travels, he observed social and religious practices, visited major pilgrimage sites, and is believed to have reached the Himalayan region, where he reportedly met Guru Hargobind Singh, the sixth Sikh Guru, in Srinagar.

His insights and experiences were compiled in his works Asmani Sultania and Parachakraniroopan, which reflect both his philosophical outlook and his keen observations of Indian society.

Nizams of Hyderabad

In the early 18th century, the Deccan witnessed a political shift as Mughal authority weakened. The Mughal administration had divided the region into six subahs, each overseen by governors under the Viceroy of the Deccan. In 1714, Asaf Jah I was appointed to this post.

A power struggle soon followed between Asaf Jah and Mubariz Khan, the governor of Hyderabad Subah, culminating in the Battle of Shakar Kheda in 1724. Asaf Jah emerged victorious and subsequently declared independence from the Mughal court, establishing the Asaf Jahi dynasty and laying the foundations for the Hyderabad State. As a result, Jalna likely transitioned from Mughal to Nizam rule, becoming part of the new political order in the Deccan.

Jalna Fort and Asaf Jah I

Jalna Fort, also known as Mastgadh, is located on the eastern edge of present-day Jalna town. The fort is traditionally associated with Asaf Jah I, the founder of the Asaf Jahi dynasty, and likely dates to the early 18th century, following his rise to power in the Deccan.

While direct records of its construction are limited, the fort’s layout and scale suggest it was intended for local administrative and defensive use, possibly to secure a key frontier settlement during a period of territorial reorganisation. In later years, the Jalna Municipal Corporation briefly utilised the site, reflecting its continued presence within the civic landscape of the town.

Maratha Presence in the Region

As the Nizams of Hyderabad rose to power following the decline of the Mughal Empire, the Marathas also remained a significant force in the Deccan. According to the Jalna Census Handbook, the Marathas maintained control over the region for approximately 62 years before eventually ceding it to the Nizams.

At its height in the 18th century, the Maratha Confederacy spanned a vast area of the Indian subcontinent, covering parts of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Karnataka, and northern India. This confederation of regional chieftains and ruling families played a major role in shaping India’s political landscape during the 18th century.

Ahilyabai Holkar and the Matsyodari Mandir in Ambad

The Maratha presence in the region was not defined by military expansion alone. One of the most visible expressions of their cultural and religious patronage is the Matsyodari Mandir, located in the town of Ambad. This Mandir, dedicated to Devi Matsyodari, was commissioned by Ahilyabai Holkar (1725–1795), the queen regent of the Holkar dynasty of Indore, who is widely known for her restoration of temples across the subcontinent.

The name Matsyodari derives from the hill upon which the Mandir is built, said to resemble a fish (matsya). Local tradition links the site to Raja Ambarisha, a legendary Hindu ruler believed to have worshipped the Devi at this location. Each October, large numbers of devotees visit the temple during the Navratri festival, maintaining its importance as a living site of devotion.

Conflict and the Battle of Assaye (1803)

Over the years, the Marathas faced increasing challenges, both from the Nizams and the expanding influence of the British East India Company. Tensions eventually led to a series of conflicts, including the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), during which the present-day Jalna district became a site of direct confrontation.

The village of Asai (historically spelt Assaye), located in Jaffrabad taluka, was the site of one of the most decisive battles of the war. On 23 September 1803, British forces led by Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington) engaged a combined Maratha army commanded by Daulat Scindia and Peshwa Baji Rao II.

The battle was fiercely contested, with the British facing strong Maratha resistance. Ultimately, the Marathas suffered heavy casualties and were forced to retreat. The outcome of the Battle of Assaye played a crucial role in the consolidation of British power in the Deccan and significantly weakened the Maratha position.

While the political consequences were far-reaching, the impact on the local population was equally profound. The battle likely disrupted agriculture, damaged village infrastructure, and strained local resources, leaving long-term effects on the residents of Asai and the surrounding areas.

The British–Nizam Alliance and Subsidiary Rule

The weakening of the Maratha Confederacy coincided with the strengthening of the British–Nizam alliance. In 1798, Asaf Jah II, the Nizam of Hyderabad, entered into a subsidiary alliance with the British East India Company, one of the earliest such agreements under the system devised by Lord Wellesley.

Under this arrangement, Hyderabad became the first princely state to accept British protection. In return, the Nizam was required to host British troops and repay debts incurred for their maintenance. While the Nizam retained nominal sovereignty, strategic control and political influence began to shift toward the British.

The agreement had long-term implications. Following the conclusion of the Second Anglo-Maratha War and especially after the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818), much of the Deccan, including present-day Jalna, came under indirect British control through the Nizam’s administration.

In 1853, the treaty was revised once again due to the Nizam’s inability to fulfil his financial obligations. Though the Hyderabad state remained officially autonomous, it was effectively brought under tighter British supervision. British Residents stationed in Hyderabad ensured that colonial interests were protected, and colonial law increasingly influenced local governance, including in regions like Jalna.

These shifts in power, administration, and policy had significant effects on Jalna’s governance structures, legal systems, and its connection to neighbouring regions, changes that would define its place within the political geography of 19th-century British India.

First War of Independence, 1857

It is said that while the Nizam of Hyderabad, as a British ally, officially refrained from supporting the 1857 Revolt, disturbances were recorded across territories under his control. Nearby Sambhaji Nagar saw unrest, and Parbhani, of which Jalna was then a part, experienced outbreaks of resistance.

Following the suppression of the revolt, administrative structures across the Hyderabad State, including regions like Jalna, underwent notable reform. The state introduced salaried tehsil and district officials, established civil and district courts, and developed new departments focused on education and public health.

Cotton and Industrial Growth in the Early 20th Century

By the turn of the 20th century, Jalna had carved out a significant role in the cotton economy of the Deccan. Its rich black soil and favourable climate made it a natural centre for cotton cultivation, but it was in processing and trade that Jalna made its mark.

According to the Imperial Gazetteer of India (1909), the year 1900 saw the presence of nine cotton ginning factories and five cotton presses in the tehsil, an impressive industrial footprint for the time. This growth was closely linked to infrastructure developments such as the opening of the Hyderabad–Godavari Railway in October 1900, which connected cotton-producing interiors like Jalna to broader commercial networks and export routes.

Its significance is further attested in the Ahmednagar district Gazetteer (1884), where it is mentioned that “Most of the cotton comes from that part of the Nizam’s country which lies between Jalna, Khamgaon, and Kulburga. Of seventy-four local cotton dealers, twenty belong to the Ahmadnagar district and the rest to the Nizam’s country, chiefly Aurangabad, Bid, Jalna, and Paithan.”

The rise of the cotton industry also spurred shifts in land use patterns. More acreage was devoted to cotton fields, and traditional hand gins gave way to mechanised processing. Cotton emerged as the largest export from Hyderabad State, and Jalna became one of its principal contributors.

This industrial and agricultural transformation, set in motion during the later years of Nizam rule, helped position Jalna as a lasting centre for cotton production, a reputation it continues to hold in present-day Maharashtra.

Post Independence

After India gained independence in 1947, Jalna remained part of the Hyderabad princely state. The Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, initially resisted joining the Indian Union. In September 1948, the Government of India carried out Operation Polo, a short military action that led to Hyderabad’s integration into the Union. Jalna, along with the rest of Marathwada, was officially merged into India on 17 September 1948.

The region became part of Hyderabad State until the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, when linguistic boundaries were redrawn. Marathi-speaking areas, including Jalna, were transferred to Bombay State. When the state of Maharashtra was formed in 1960, the area that forms the district currently was divided between Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (then Aurangabad) and Parbhani districts.

Years later, after growing demands, on 1 May 1981, Jalna was established as a separate district. It included Jalna, Bhokardan, Jaffrabad, and Ambad taluka from Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district, and Partur taluka from Parbhani.

Following its establishment as a separate district, Jalna underwent administrative and infrastructural changes. Agriculture remained the primary occupation, with gradual expansion in irrigation and crop production.

Industrial activity developed around Jalna town, particularly in sectors such as steel re-rolling and agro-processing. Industrial areas were established by the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) to facilitate local enterprises. These developments contributed to employment and local economic activity.

Sources

Aditya Ramanathan. 2016. “Battle of Assaye: When British Blades Triumphed Over Maratha Guns.” The Wire.https://thewire.in/history/assaye-when-briti…

George Michell; Mark Zebrowski. 1999. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates. Vol. 7. Cambridge University Press.

Govt. of Maharashtra. 1967. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Parbhani District. Directorate of Government printing, Bombay.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/Parbha…

Hastings Fraser. 1865. Our Faithful Ally The Nizam. Smith Elder and Co. London.

His Highness The Nizam's Government. 1884. Gazetteer Of Aurangabad. Times of India Press, Bombay.

Itihaas Ki Goonj. 2021.जालना की 444 साल पुरानी काली मस्जिद का इतिहास. Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gqx1sMHq3Ko

James M Campbell. 1884. Gazetteer Bombay Presidency: Ahmadnagar Vol-i.Government Central Press, Mumbai.https://www.gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cu…

Madan Singh Chouhan, Tejas Garge, Kishor Chalwadi, and Amol Kulkarni. 2015. “Report on Archaeological Investigations in Girija River Valley, Districts Aurangabad and Jalna, Maharashtra.” Vol 3.Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology..https://heritageuniversityofkerala.com/Journ…

Mirza Mehdy Khan.Census of India, 1891, Volume XXIII: His Highness the Nizam’s Dominions. Report on the Census Operations, Part I (Chapters I to VI). Jehangir B. Marzban & Co, “Advocate of India” Steam Press, Mumbai.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

RJ Dipak Wankhade. 2020. Kali Masjid Jalna | Hammam | जालना का हमाम | Jalna City | Marathwada Tourism | RJ Dipak Wankhade. Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oGX-bnG7-io

Samir Biswas. 2001. District Census of Handbook: Jalna District. Govt. of Maharashtra, Census of India.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

Syed Hossain, C. Wilmot eds. 1883. Historical and Descriptive Sketch of His Highness the Nizam's Dominions, Times of India Steam Press, Mumbai.https://indianculture.gov.in/rarebooks/histo…

The Imperial Gazetteer of India: The Indian Empire, Vol. IV – Administrative, New Edition. 1909. Clarendon Press, Oxford.https://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazettee…

Upinder Singh. 2016. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century: From Stone Age to the 12th Century.Pearson, UP.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.