Contents

- Literary & Performance Arts

- Shahiri and Powada

- The Shahirs of Kolhapur

- Natak (Theater)

- Music

- Cinema

- Handicrafts

- Kolhapuri Chappal

- Crafting Process

- Kolhapuri Saaj

- Stone Carving

- Bamboo Crafts

- Cultural Programs

- Rankala Mahotsav

- Creative Spaces of the District

- V.S. Khandekar Memorial Museum

- Hans Talkies

- Venus Talkies

- Shahu Talkies

- Uma Talkies

- Artists

- Pirajirao Sarnaik

- Ranjit Desai

- Sources

KOLHAPUR

Artforms

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Literary & Performance Arts

Shahiri and Powada

Shahiri, also known as Powada, is a traditional form of oral literature from Maharashtra, particularly associated with Kolhapur. It is characterized by ballads that recount historical events, especially acts of bravery, often performed with musical accompaniment. The performers of this art form are referred to as Shahirs.

The origins of Shahiri are commonly associated with the period of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, whose leadership and military campaigns inspired a range of narrative compositions. Over time, Powadas became a popular medium to celebrate Maratha valor and convey messages of social and political importance to the public.

In Kolhapur, the art form gained significant momentum under Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, who supported a wide range of artistic practices, including Shahiri. His promotion of Rajashray (royal patronage) allowed Shahirs, artisans, and performers to practice their craft with institutional support. During this time, Kolhapur became known as Kalanagari, meaning “City of Artists,” a title still referenced by locals today.

The Shahirs of Kolhapur

The tradition of Shahiri in Kolhapur was shaped by generations of Shahirs whose compositions reflected not only historical events but also the changing social and political landscape of their time. Under Shahu Maharaj’s patronage, Shahirs like Ramchandra Narhar Mali, Lahari Haider, and Ishwara Mali became central figures. Their performances, accompanied by instruments such as the daf, tuntune, and kade-dholaki, were a key part of public gatherings, where powadas praised Maratha rulers and warriors and upheld regional cultural values.

The recognition given to Shahirs during this period reflected their important role in society. A notable example is found in the preface of Shahir Done’s book, which recounts his performance during the wedding of Shrimati Radhabai Akkasaheb Maharaj. Moved by the powada, Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj honored Done with the title Shirpechwale, a silver medal, and a letter of commendation. This event illustrates how Shahiri, beyond performance, was acknowledged as a respected and integral part of cultural life in Kolhapur.

In the years that followed, Shahiri continued to evolve through the work of performers like Shahir Lahari Haider, who became known for broadening the thematic range of the tradition. His compositions explored social and historical topics, including a powada on the Russian Revolution, an uncommon subject for the time. His work reflected a wide engagement with contemporary and historical events, contributing to the evolution of Shahiri in a changing cultural context.

Haider also mentored Pirajirao Sarnaik, who would become one of Kolhapur’s most well-known Shahirs. Sarnaik’s career spanned several decades, with performances across diverse platforms, including Marathi cinema. His work helped to sustain the tradition during a period of cultural transition, as public tastes and entertainment formats began to shift.

Alongside performance, the literary side of Shahiri was enriched by writers such as M.N. Nanivadekar and G.D. Madgulkar. Though Madgulkar did not perform powadas himself, his compositions on Lokmanya Tilak and Sambhaji Maharaj were presented by Shahirs like Sarnaik and Shahir Nikam. This collaboration between writers and performers perhaps helped to preserve and adapt Shahiri’s narratives for new audiences.

Today, Shahiri is viewed by many as a dying art form. Once central to public storytelling and education, it now faces declining interest, especially among younger audiences. Many practitioners note that while the form remains valued for its historical and artistic significance, its place in contemporary cultural life is increasingly uncertain.

Efforts to preserve and adapt Shahiri continue, led by performers and writers committed to sustaining the tradition. Through performance, education, and collaboration, they aim to ensure that Shahiri remains not only a link to the past but also a living art form that can continue to engage new generations.

Natak (Theater)

Kolhapur has long been a cultural epicenter for Marathi theater, with its roots deeply embedded in the region’s rich performing arts heritage. It is widely believed that the district’s connection to the theatrical world began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, growing under the influence of visionary leaders like Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, whose support for the arts was as revolutionary as his efforts in social reform.

Even before Shahu Maharaj's reign, many recall that the region had a rich tradition of folk performances such as Tamasha, Lavani, Kirtan, Dindi, and Bhajan, which laid the groundwork for the growth of Marathi theater. As professional theater troupes started to form in Kolhapur, the landscape of performance art began to change. It is said that groups like the Ichalkaranji Natak Mandali, Altekar Natak Mandali, and Sanglikar Natak Mandali brought new energy to the stage, performing plays that captivated audiences and helped establish a thriving cultural atmosphere.

Shahu Maharaj’s personal interest in theater is said to have begun when he saw a performance of Sasikala-Ratnapal, a Marathi adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, performed by Rajaram College students during his adoption ceremony in 1884. According to local accounts, this moment sparked his lifelong passion for drama, inspiring him to promote theater as an important part of the region’s culture. College students at Rajaram College continued to perform plays, with venues like the Bhavani Mandap hosting productions, which further solidified the growing importance of theater in Kolhapur.

Local theater enthusiasts often say that one of the turning points in Kolhapur's theater history was when the humorous play Vinod, written by Madhavrao Joshi and performed by well-known figures like V. Shantaram and Bhalji Pendharkar, was staged at the Keshavrao Bhosale Natyagruha. Since then, this venue has become a major hub for all kinds of performances, from vyavsayik natak (commercial theater) to prayogik natak (experimental theater), continuing to host a wide variety of theatrical works.

The district’s commitment to nurturing talent is reflected in the many acting classes and cultural programs available, with Shivaji University offering a Master of Performing Arts course. Local colleges have active cultural groups that participate in youth festivals, producing a variety of performances, from one-act plays (ekankika) to street theater, which reflect the diverse interests and creativity of the younger generation.

However, despite the deep-rooted tradition of theater in Kolhapur, there is a prevailing view that it is mostly pursued as a hobby rather than a professional career. As Parth Desai, a local dramatist, points out, "If children were given proper theoretical and practical training in theater, with the option to pursue it as a career, there is no doubt they would excel. Unfortunately, many are unaware of the rich history of theater in our own region."

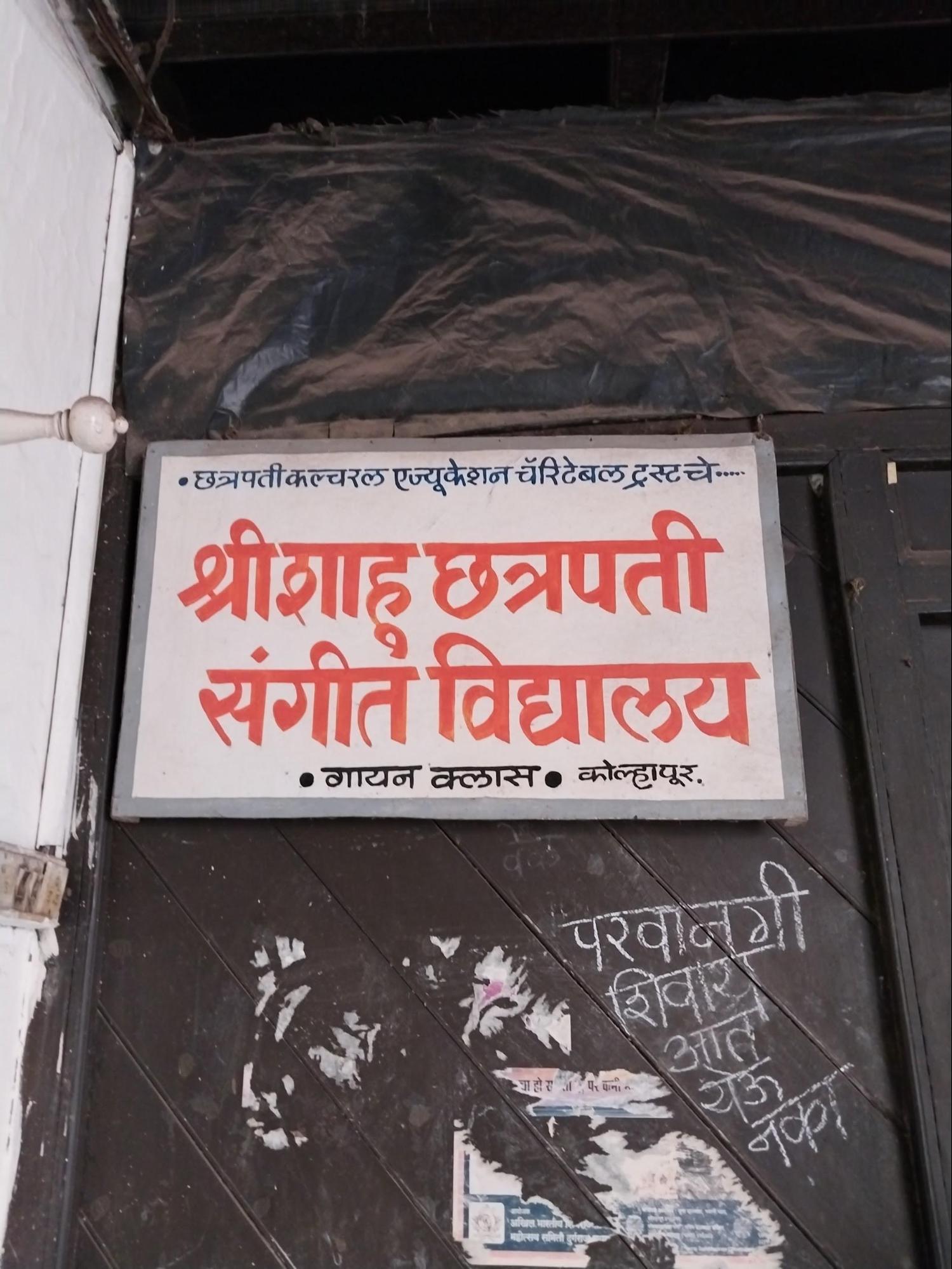

Music

Music has historically played an integral role in the cultural life of Kolhapur. The region is associated with a strong tradition of both classical and folk music, and has long been known for its engaged musical audience, often referred to locally as rasiks (connoisseurs).

The development of Kolhapur’s musical institutions is often linked to the period of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj’s reign in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Through patronage, he supported various forms of artistic expression, including music, theatre, and visual arts. During this time, several key institutions were established. In 1883, the Gayan Samaj was founded as Kolhapur’s first organized society for the promotion of music and vocal performance. This was followed by the formation of the Deval Club in 1892, which provided a platform for musicians to study, perform, and collaborate.

But perhaps the most significant chapter in Kolhapur’s musical history came with the arrival of Gaan Alladiya Khan Saheb, a noted figure in Hindustani classical music and founder of the Jaipur-Atrauli gharana. It is often said that Shahu Maharaj invited Alladiya Khan to his court, along with other musicians from his family, including Haider Khan and Manjikhan. During his stay here, Alladiya Khan contributed to the dissemination of Jaipur gharana’s stylistic traditions in Kolhapur, particularly its dhrupad-based vocal forms.

Concurrently, Kolhapur attracted folk musicians from the surrounding region. Performers such as Tukarambuva Sarnaik, Panditrao Karambelkar, and Krushna Bagnikar rose to prominence at this time, noted for blending elements of classical and folk music in their compositions.

Today, Kolhapur continues to uphold its musical legacy through various Sangeet Vidyalayas (music schools) and cultural institutions, many of which trace their origins to the initiatives taken during Shahu Maharaj’s reign.

Cinema

Kolhapur was one of the early centres of filmmaking in India during the 20th century, particularly in the silent film era. While major film industries later developed in Mumbai and Pune, Kolhapur played a formative role in the development of regional cinema in Maharashtra.

The district’s association with cinema dates back to the early 20th century, during the reign of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, whose patronage extended to emerging art forms, including filmmaking. During this period, Baburao Painter, a local artisan, became interested in film technology after observing a projector in use. He constructed his own version of the device and soon after, in the early 1920s, founded the Maharashtra Film Company.

![Baburao Painter , the pioneering filmmaker and founder of Maharashtra Film Company, is credited with shaping the early years of Kolhapur's cinematic legacy.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/artforms/baburao-painter-the-pioneering-filmmaker-an_iH3PiFG.png)

Baburao Painter directed Sairandhri in 1920, drawing upon Indian epics for its subject matter. Over the following decade, the studio produced around 20 films, and Kolhapur developed into a regional centre for cinema. The studio attracted actors, technicians, and artists from across Maharashtra. Notable among them were V. Shantaram and Zunzarao Pawar, who would later become prominent figures in Indian cinema.

In 1929, internal disagreements led to significant changes within the studio. V. Shantaram, along with K. Dhojar, V. Damle, and S. Fattelal, departed and went on to establish the Prabhat Film Company, which initially operated in Kolhapur before relocating to Pune. Following the departure of key personnel and the exit of Baburao Painter, the Maharashtra Film Company ceased operations, marking the end of Kolhapur’s first phase of film production.

The relocation of the Prabhat Film Company created a gap in local filmmaking activity. Although Kolhapur had played a formative role in early Indian cinema, its prominence declined as Mumbai and Pune emerged as major production centres.

In the 1940s, Chhatrapati Rajaram Maharaj, in collaboration with Dadasaheb Nimbalkar, founded Kolhapur Cinetone in an effort to revive the city’s film industry. Despite this initiative, the rise of larger film studios in Mumbai and Pune meant that Kolhapur could not regain its earlier position as a centre of production.

While the district’s role in filmmaking diminished, Kolhapur continued to contribute to Indian cinema in other ways. Its surrounding landscapes, including locations such as Panhala and Jyotiba hills, became popular with filmmakers seeking scenic settings. Kolhapur is further linked to the invention of the Firta Rangmanch, a mobile theatre stage first built in Udyamnagar.

Handicrafts

Kolhapuri Chappal

Kolhapuri chappals, locally known as paitaan (पायताण), are traditional handcrafted leather sandals from Kolhapur. Renowned for their durability and distinctive design, they are a deeply rooted aspect of local identity. Their cultural presence is reflected in common expressions, such as the saying “पायताणच हानीन” (“I’ll hit you with a Kolhapuri chappal”), which illuminates both their everyday use and symbolic place in the region’s social fabric. The chappals are recognized for their distinctive designs and were awarded a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, marking them as a culturally unique and protected product.

The craft of Kolhapuri chappal-making is traditionally linked to the Chamar community and is believed to have originated in the 12th century in Bidar. According to legend, an artisan named Haralayya crafted leather sandals for Basaveswara, minister to King Bijjal. These sandals, made from vegetable-tanned leather, were considered sacred. The story remains part of the oral tradition surrounding the origins of the craft.

The production of chappals was later formalized during the reign of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, who organized artisans into the twelve balutedars, a hereditary service system. Chappal makers were classified under the Chambhar (Charmakaar) community, with related roles performed by the Mahar (involved in hide extraction) and the Dhor (leather tanning).

While chappal making had been practiced for centuries, many locals say that it was only during the reign of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj that the craft truly flourished. Shahu Maharaj not only wore Kolhapuri chappals himself but also recognized them as a significant cultural and economic activity. His patronage elevated the craft, ensuring its continued growth and recognition.

Crafting Process

Kolhapuri chappals are made from vegetable-tanned leather using largely manual techniques passed down through generations. Though some aspects of the process have incorporated machinery, the majority of the work remains artisanal.

The process begins with chemically treated leather sheets, which are cut into shape using stencils and small cutting machines. The sole is formed by bonding two layers of leather, trimmed for uniformity.

The upper and lower sole layers are stitched by hand, requiring precision to ensure both durability and comfort. Leather straps are cut using a tool called a raapi. These are braided into veni (decorative leather braids), often featuring intricate motifs like chandni (spirals) and gonda (round elements), coated in a special adhesive to ease weaving.

The straps are measured and fitted onto the chappal. This step requires a high degree of precision, especially when dealing with larger, intricate straps that feature decorative elements such as gonda (small beads) and braids.

After the structure and design are completed, the chappal undergoes finishing touches. The edges are smoothed using a grinding tool, giving the piece a clean, polished look. Tanning and dyeing follow, where the leather is soaked in water to help the dyes absorb fully, a step that adds both durability and rich color. Shades like brown, black, and yellow are the most common.

The entire process can take up to a day for a single pair. These chappals are sold in markets like Chappal Line in Kolhapur, while production centers are primarily based in Jawahar Nagar, Karvir, and other parts of Kolhapur.

Despite the craft’s rich legacy and popularity, many artisans today are reluctant to continue the craft or encourage their children to do so. One artisan’s family member explained they help out occasionally, but their focus is on other careers — a sentiment echoed across many families in the trade. Low profits and competition from cheap imitations have made it difficult for artisans to sustain their work.

Even so, some remain hopeful. They believe that with proper investment and support, especially through modern tools and fair compensation, the craft can grow and adapt without losing its roots.

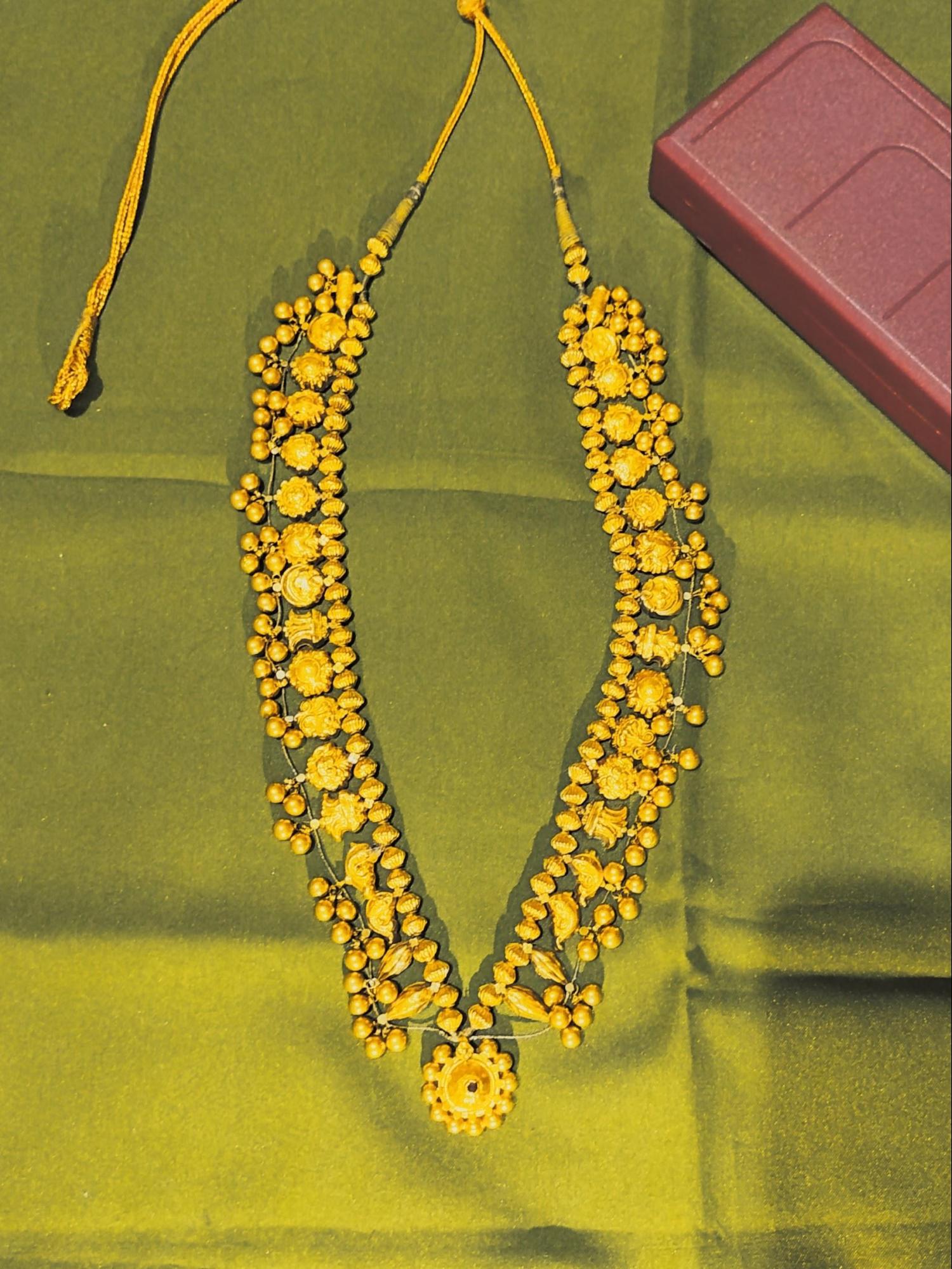

Kolhapuri Saaj

In Kolhapur, one of the most cherished possessions in a woman’s life is often her saaj, a traditional necklace that holds both cultural and personal significance. Carefully crafted by local artisans, the Kolhapuri saaj has been part of the region’s identity for generations. Worn not only as jewelry but as a symbol of heritage, the saaj is considered a mark of marital status, family lineage, and tradition.

Traditionally, the saaj is worn by married women and is known as सुवासिनीचे लेणं, the adornment of a married woman. It is typically given by a mother to her daughter, serving as both a family heirloom and a symbol of the continuity of tradition. Aside from its ornamental value, the saaj is believed to offer protection and blessings, and is often seen as a tangible link between generations.

The design of the Kolhapuri saaj is distinct, featuring intricate gold work and a series of symbolic motifs, including the Tayit (sacred emblem), Shankha (conch), Chakra (wheel), Vagh Nakh (tiger claws), and the tortoise. Each element carries spiritual or cultural meaning, often tied to nature, deities, and concepts of prosperity and protection.

A defining feature of the saaj is the petal-shaped pendant, which often includes a backdrop of Mahalakshmi, depicted through motifs like the prabhaval or kirtimukh, a stylized lion or tiger face to symbolize divine protection. One of the most traditional pendants includes a figure of Krishna standing atop Brahma.

The traditional Kolhapuri saaj is typically made with at least 25 grams of gold, though the weight and materials can vary.

Some saajs are crafted entirely from gold, while others feature gold-plated laakh beads, making the piece more accessible. The individual components of the saaj are shaped using metal molds, known as daay, many of which have been passed down through generations of artisans, ensuring consistency in design and detail.

Over time, the design of the saaj has evolved while maintaining its core structure. Milind, a local jeweler, reflects on these changes: “The earliest saajs featured Krishna’s face, symbolizing time and protection. Later, tiger claws were introduced, crafted from pure gold. Today, many saajs use laakh, and the designs vary slightly, but the essence remains.”

Historically, saajs were often adorned with precious stones such as diamonds and rubies, but shifts in consumer preferences and material costs have led to the increased use of laakh, either as a base or coating. Despite these adaptations, the craft remains highly skilled, with artisans continuing to use traditional techniques to create each piece.

While the saaj is the most iconic ornament in Kolhapur, it is part of a broader jewelry tradition. The Thushi, a simpler necklace made from closely strung small gold beads, is often worn during festivals or with Paithani sarees. Another staple is the Chitak, a minimalistic choker typically worn by older women for daily use, paired with sarees or salwar kameez. Though understated, these pieces reflect the everyday role of jewelry in the lives of women in Kolhapur, each holding its own cultural significance.

Stone Carving

In Kolhapur, stone carving has been practiced for generations, sustained largely by the Vaddar community, who have passed the craft down through families. Many artisans begin learning the trade in early childhood, sometimes as young as seven, watching and assisting elders in workshops. Today, a third generation of carvers continues the work in areas like Panhala-Jyotiba Road, Csiber Chowk, and Juban Nana, where small workshops remain active.

For decades, this craft was closely tied to daily life. Before the spread of electric grinders and food processors, stone utensils were found in nearly every kitchen. Tools like the pata varvanta (grinding stone), khalbatta (small mortar), ukhal (large mortar), musal (pestle), and jata (grinding slab) were used to prepare spices and pastes. Grinding was often a daily task, physically demanding, typically done by women, and part of the routine of cooking. Many remember growing up around these tools, watching as chutneys and masalas were ground by hand.

The use of stone utensils declined steadily from the mid-20th century, as electric appliances replaced manual grinding in most homes. However, many people continue to use and value them, especially for preparing small quantities of spices. The market for stone utensils in the district, notably, also extends beyond Kolhapur, with buyers from areas such as Vashi, Haldi, Bachani, and Radhanagari.

Artisans usually source raw stone from Top-Sambhapur village, which is brought to Kolhapur for shaping. Finished items are priced between ₹150 and ₹1000, depending on size and craftsmanship. In addition to kitchen tools, artisans also produce Tulsi Vrindavans. Daily earnings for artisans typically range from ₹500 to ₹600, depending on orders. While the work is labor-intensive and margins remain low, many continue in the trade.

Bamboo Crafts

The Burud community in Kolhapur has long been known for its bamboo craftsmanship, creating items such as torans, baskets, and other everyday goods. Passed down through generations, this craft has been a central part of their livelihood and cultural identity.

The connection between the community and bamboo crafting is rooted in local folklore, with stories that link the Burud artisans to both the spiritual and practical use of bamboo. One tale recounts how Goddess Parvati was gifted a bamboo basket by a Burud artisan for her ritual at the banyan tree, while another speaks of a mistake that solidified their association with the craft.

Bamboo crafts were once integral to the Burud community’s livelihood, but as modern materials like plastic have become more common, demand has naturally declined. Today, many artisans have moved on to other professions to make ends meet, yet the craft endures in some corners of the district, where it continues to be valued by those who seek out traditional, handmade goods.

Cultural Programs

Rankala Mahotsav

The Rankala Mahotsav is an annual cultural festival held between January and March in Kolhapur. The festival takes place on the lawns near Rankala Lake and features various performances in music, dance, and drama. Organized by the Kolhapur Municipal Corporation, the event showcases the artistic heritage of the region, providing a platform for both established and emerging artists.

Creative Spaces of the District

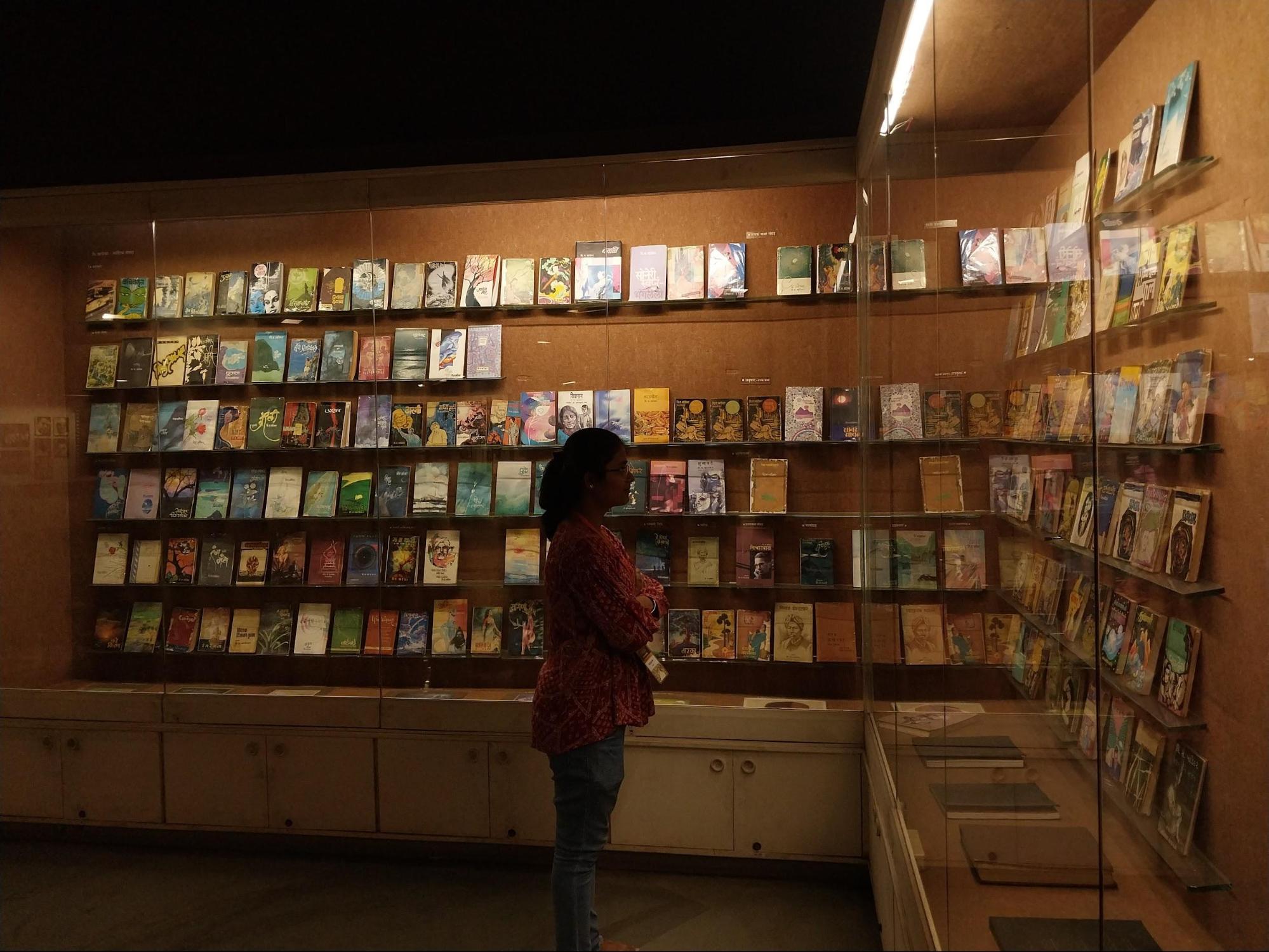

V.S. Khandekar Memorial Museum

The V.S. Khandekar Memorial Museum, located at Shivaji University, is dedicated to the life and works of the renowned writer V.S. Khandekar, a Jnanpith Award recipient. Established in 2005, the museum offers a glimpse into Khandekar’s literary journey, showcasing photographs, manuscripts, and awards.

Hans Talkies

Kolhapur, as many locals regard it, has long been a sanctuary for cinema lovers. From the grand early cinemas to the smaller halls screening Marathi films, these venues have shaped the district’s cultural fabric. The journey of Kolhapur’s cinema, from the days of silent films to the rise of talkies, reflects a story of transformation, and it all began with Hans Talkies.

Hans Talkies was Kolhapur’s first cinema hall and was founded by Margu Anna Sangar with support from Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj. Located behind Vitthala Mandir, it initially screened silent films and became the first theater in the city to show Raja Harishchandra, India’s first sound film, in 1932. This screening attracted large crowds from both Kolhapur and the surrounding villages.

Over time, Hans Talkies closed, but its legacy continued through Jalsa Kendra, which opened at the same location. After facing controversies, the building was repurposed in 1965 into the Ganesh Mangal Office by Bapu Navare, who preserved the original structure. Today, this remains a reminder of Kolhapur’s early connection with cinema.

Venus Talkies

Venus Talkies, another key landmark in Kolhapur’s cinema history, opened on June 6, 1931, by Tayyab Ali Bohri. Bohri, an innovative entrepreneur, introduced several unique features to the theater. During the silent film era, it is said that he offered free transportation for moviegoers and organized live dance performances during intermissions to keep audiences engaged.

Bohri’s creative marketing strategies, which perhaps predate the term "event cinema", helped establish Venus Talkies as one of the city's most popular entertainment venues. Many locals still recall the theater’s approach with fondness, appreciating its role in bringing cinema to the community and enhancing the moviegoing experience.

Shahu Talkies

Shahu Talkies, established in 1946, was opened to honor Kolhapur’s royal heritage on the day of Shahaji Maharaj’s coronation. Founded by Rao Bahadur D. M. Bhosle, the theater was associated with Kolhapur’s royal history and remained a prominent venue for cinema in the city.

Uma Talkies

Originally named Sandhya Talkies, Uma Talkies became well-known for screening English films during a time when most theaters in Kolhapur focused on Marathi and Hindi films. The theater attracted a diverse audience and contributed to the variety of cinematic experiences available in the district.

Artists

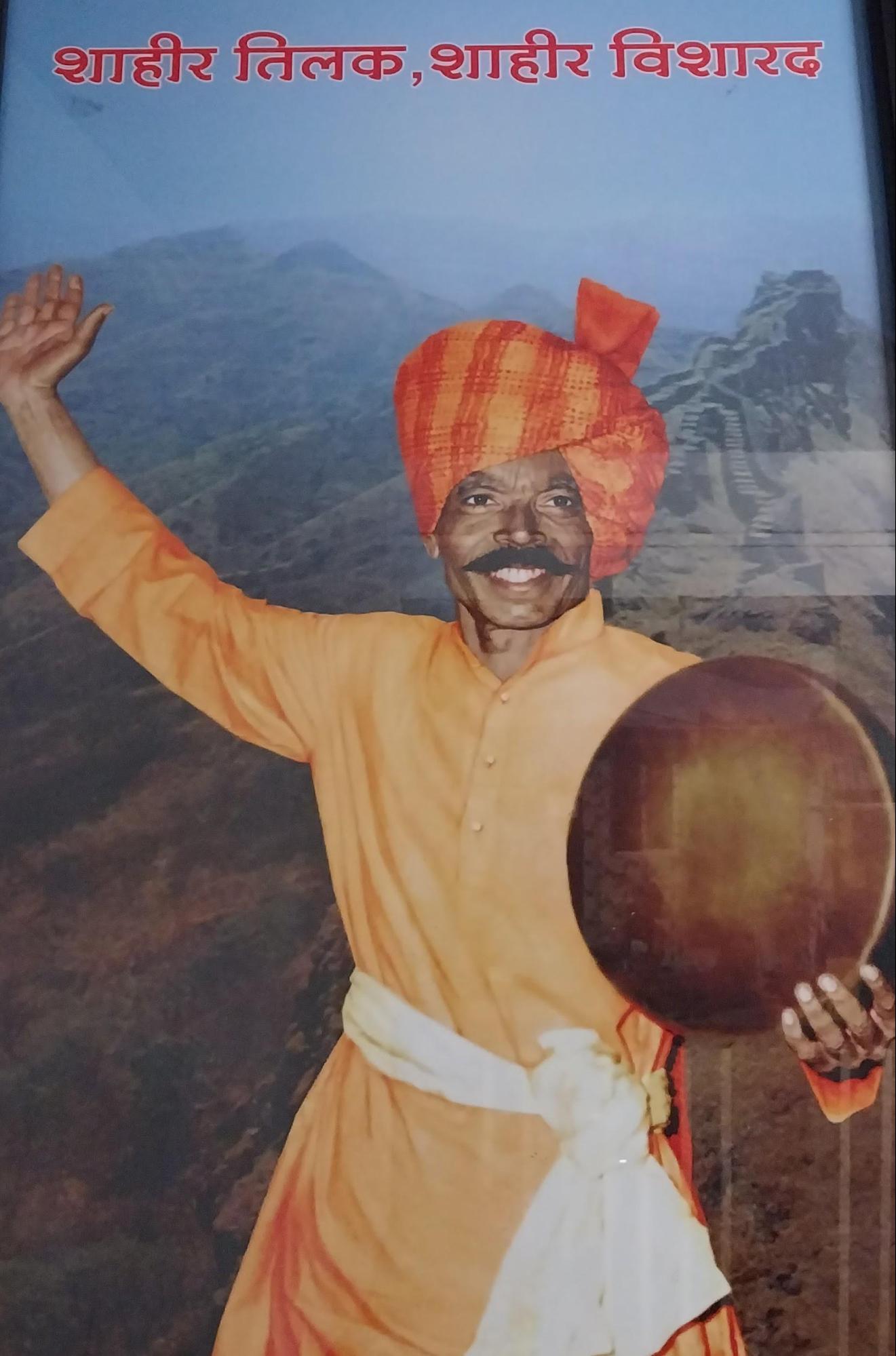

Pirajirao Sarnaik

Pirajirao Sarnaik was a prominent Marathi Shahir and a key figure in the revival and popularization of Powada, the traditional Marathi ballad. Sarnaik’s introduction to Shahiri began during his childhood at the Bavdekar Talim, a traditional martial arts school, where he was exposed to the martial game Dandpatta and Powadas celebrating Maratha heroism.

Over the course of his six-decade career, Sarnaik became one of the foremost practitioners of Powada, performing extensively across Maharashtra. He was awarded the Shahir-Tilak Award in 1936 and, in 1950, received the title Shahir-Visharad from the Kolhapur Chhatrapati in recognition of his contributions to the art.

Sarnaik was mentored by Narayanrao Yadav, who introduced him to Shahir Lahari Haider, a renowned Powada performer. Under Haider's guidance, Sarnaik refined his skills and contributed significantly to the preservation of the tradition. He also appeared in the Marathi film Savkaari Pash, which helped bring Powada to a wider audience.

Ranjit Desai

Ranjit Desai (b. 1928 – d. 1991) was a renowned Marathi novelist, playwright, and short story writer, best known for his historical fiction. His works, particularly those focused on the Maratha Empire and its leaders, have had a significant impact on Marathi literature.

![Ranjit Desai[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/artforms/ranjit-desai2-f215d107.png)

Desai’s most notable works include Swami, which explores the life of Madhavrao Peshwa, and Shriman Yogi, a biographical novel about Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. These works blend historical events with imaginative storytelling, providing readers with both a deep understanding of the period and insight into the complexities of leadership. He received several accolades during his career, including the Sahitya Akademi Award (1964), the Maharashtra Rajya Award (1963), and the Padma Shri (1973). His works continue to resonate with readers interested in the history of Maharashtra.

Sources

Economic Times. 2019. Kolhapuris: The famous leather chappal get Geographical Indication tag. The Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/po…

Granthyatra. 2021. Granthyatra Episode 50 - Swami - A historical novel by Ranjit Desai. Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ij2D9VsUG_I

Harper Collins Publishers India, Ranjit Desai. Harper Collins.https://harpercollins.co.in/author-details/r…

Kolhapur Tourism,Festivals Celebrated in Kolhapur. Destination Kolhapur. https://www.kolhapurtourism.org/festivals-ce…

Names of 'Powade Shahir' (listed by M. N. Sahasrabuddhe in his book.)Powade.com Accessed March 18, 2025,https://www.powade.com/essays/listofsingers.…

R.E. Enthoven. (1920).The tribes and castes of Bombay Vol. I. Bombay: Government Central Press.https://archive.org/details/dli.csl.8508

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.