Contents

- Bahubali Jain Mandir, Kumbhoj

- Bhavani Mandap

- Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and Tararani's Takht

- The Maratha Empire in Kolhapur: From Shivaji Maharaj to Tarabai

- Shirol and the Inaami Village

- ISKCON Mandir

- Jahaj Mandir

- Jyotiba Mandir

- Kopeshwar Mandir, Khidrapur

- Epic Connections

- The Construction of the Mandir and its Legends

- Architectural Features

- Festivals & Rituals

- Kukuteshwar Mandir

- Laxmi Vilas Palace

- Post-Independence Role and Preservation

- Mahalakshmi Mandir

- Historical and Cultural Significance

- Historical and Architectural Features

- Festivals and Rituals

- Nagarkhana

- Narsoba Chi Wadi Mandir

- Founding and History

- Rituals and Practices

- Panhala Fort

- Etymology and Nomenclature

- The Fort's Early History and Cultural Legacy

- The Influence of the Bahmani and Adilshahi Dynasties

- Strategic Importance and Maratha Influence

- The Later Years and Decline

- Architectural Significance

- Darugola Kothar

- Ambarkhana

- Dharma Kothi

- Kalavantin Mahal

- Pusati Buruj

- Someshwar Mahadev Mandir

- Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Mandir

- Parashar Guha

- Wagh Darwaja

- Teen Darwaja

- Sajjakoti

- Chhatrapati Tararani Rajwada

- Chhatrapati Sambhaji II Mandir

- Pant Amatya Bavdekar Wada

- Panyacha Khajina

- Pavankhind

- Ramling Mandir

- Shalini Palace

- Shankar (Mahadev) Mandir, Kasba Beed

- Shri Binkhambi Ganesh Mandir

- Siddhagiri Math (Museum)

- Temblai Devi Mandir

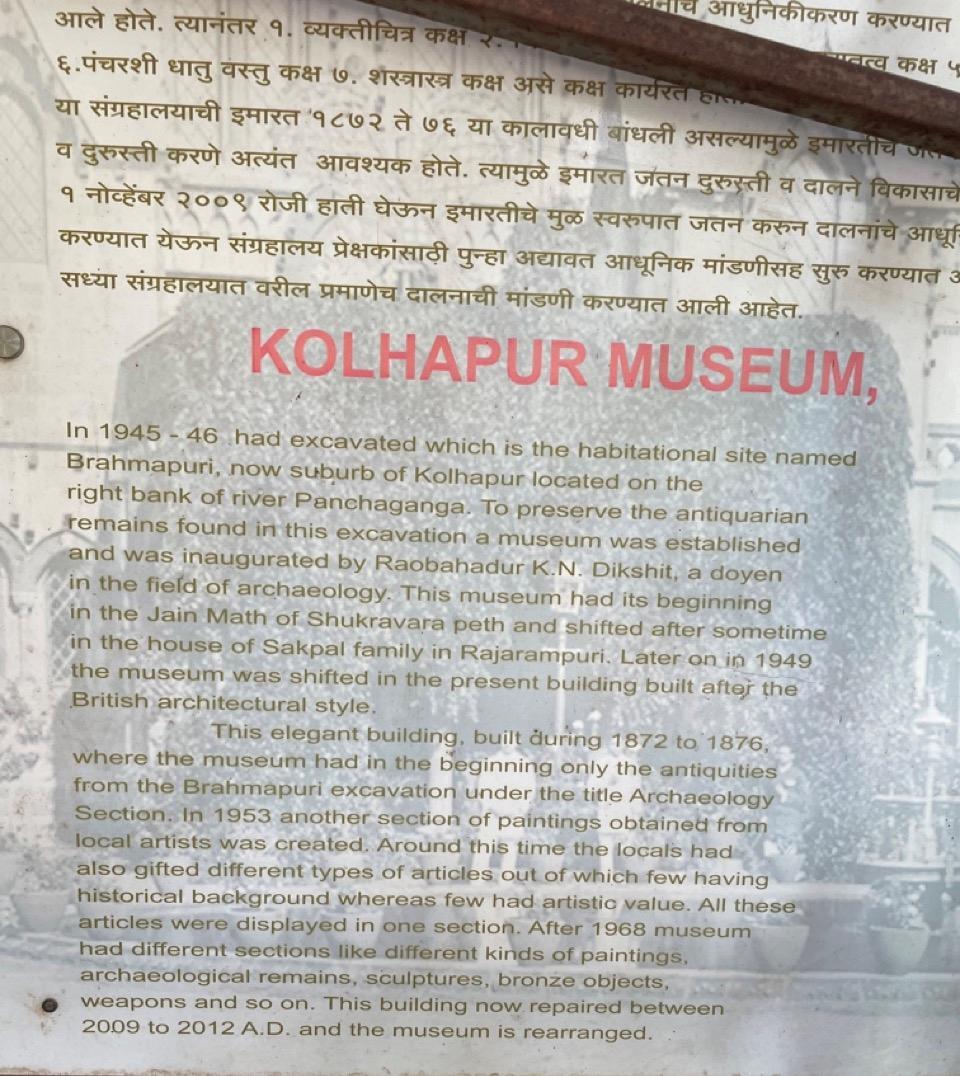

- Town Hall Museum

- Historical Significance & Relics

- Vitthal Birdev Mandir

- Vitthal Rukmini Mandir, Shendur

- Wilder Memorial Church

- Sources

KOLHAPUR

Cultural Sites

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Bahubali Jain Mandir, Kumbhoj

The Bahubali Jain Mandir in Kumbhoj, located in Hatkanangale taluka of Kolhapur district, is dedicated to Shri Bahubali Maharaj, a revered ascetic and scholar. According to local lore, Bahubali Maharaj, who lived in the region around 200 years ago, was instrumental in protecting the area from wild animals. He was known for his wisdom, kindness, and compassion, virtues highly regarded by Jain ascetics.

In 1963, a 28-foot statue of Bahubali Maharaj was installed in the Kayotsarg position, mirroring the iconic Gomateshwar statue at Shravanabelagola in Karnataka. The temple is recognized as an Atishaya Kshetra, or "a place of miracles," a term that reflects its spiritual significance.

The temple is a popular pilgrimage site for the Jain community and is visited by devotees seeking spiritual enlightenment. It is believed that around 350 years ago, Shri 108 Bahubali Maharaj from Sangli visited the area for Tapasya (meditation) and gained profound wisdom. His presence is said to have protected the site from negative forces, ensuring a safe and sacred space for pilgrims.

Every twelve years, the temple organizes the Mahamastakabhishek, a significant seven-day religious event that is a highlight of the Jain religious calendar. The temple also hosts a Brahmacharyashram, a Gurukul for boys, where young aspirants are trained in spiritual knowledge.

Bhavani Mandap

Within the ancient walled city of Kolhapur, just a short distance from the revered Mahalakshmi Mandir, stands a historic building known as Bhavani Mandap, which quietly bears witness to the city's rich past. For the many visitors who come to the Mahalakshmi Mandir, this building often goes unnoticed, despite the centuries of history it holds.

The building, with its elegant tiled floors and expansive central hall, stands as a testament to the royal family's lasting influence on the city. Inside, there are many notable features to explore, but at its core is Bhavani Chowk, where the murti of Bhavani Devi quietly draws the attention of both residents and visitors.

It is believed that the building was constructed between 1828 and 1829 by Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj and was built for a significant occasion, the wedding of his daughter, Radhabai, to Maharaja Tukojirao Pawar of the Maratha princely state of Dewas.

However, historical records, such as the Kolhapur Gazetteer, suggest a slightly different version of the site’s evolution. According to the district Gazetteer (1960), the Old Palace, within which the family’s kul devi, Bhavani, was housed, is described as follows: “The Old Palace stands near the Mahalaxmi Temple to the south-east of the temple. It was built more than 200 years ago. Some portions of this Palace were set on fire and destroyed in the insurrection of 1813 by Sadalla Khan, and they had to be rebuilt from time to time.” This historical context may explain why the structure is named Bhavani Mandap.

Among the most cherished items in the Mandap are the handprints of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, cast in silver and brought from Sindhudurg Fort. The building also houses various government offices and offers rooms for guests. On the first floor, there is a statue of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, who played a crucial role in shaping Kolhapur’s identity. A hidden gem, as locals state, in the Mandap is the underground passage, said to lead to Panhala Fort, adding an element of mystery and intrigue to the building.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and Tararani's Takht

The Maratha Empire, founded by the visionary Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, remains one of the most significant chapters in Indian history. His legacy is not just a tale of military conquests, but also one of governance, resilience, and a deep sense of loyalty to his people. While Shivaji Maharaj’s reign laid the foundation for Maratha power, his daughter-in-law and successor, Maharani Tarabai Bhosale, played a crucial role in maintaining that legacy during some of the most turbulent times the Maratha state faced. The Takht (throne) built in Shirol, a village near Kolhapur, stands as a lasting tribute to their leadership and the unwavering devotion of the Marathas.

The Maratha Empire in Kolhapur: From Shivaji Maharaj to Tarabai

The Takht in Shirol is a significant historical monument that encapsulates the tumultuous political landscape of the Maratha Empire. Understanding its legacy requires a deeper look into the political history of Kolhapur, particularly the role played by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and his successors in shaping the empire’s future.

His legacy continued after his death in 1680, despite mounting challenges from the Mughals under Emperor Aurangzeb. It was his sons, Sambhaji Maharaj and later Rajaram Maharaj, who carried forward the battle to protect Maratha sovereignty. The struggle, however, intensified after Rajaram died in 1700, leading to significant political instability.

Maharani Tarabai Bhosale, widow of Rajaram, stepped into the role of regent for her son, Shivaji II, and became a formidable leader. As the regent for her son Shivaji II, she became the central figure in keeping the flame of Maratha resistance alive against the Mughals. Richard M. Eaton in A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761 (2000) remarks that Tarabai’s leadership was essential in maintaining resistance against the Mughal Empire.

Despite her military prowess and strategic acumen, the rise of Shahu Maharaj, the son of Sambhaji Maharaj, sparked a political struggle within the Maratha Empire. BM Jadhav and BD Khane (1994) in their dissertation note that Shahu, with the support of Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath, challenged Tarabai’s claim to the throne.

Following a tense political battle, Shahu Maharaj succeeded in claiming control over the Maratha Empire, effectively sidelining both Tarabai and her son. Nonetheless, Tarabai, unwilling to give up, established a rival court in Kolhapur, where she crowned her son, Shivaji II, as the first Chhatrapati of Kolhapur. Appasaheb Pawar, an important figure in documenting Maratha history, particularly focusing on the Kolhapur State, described Tarabai as "the first female ruler of the Marathas and the founder of the Kolhapur 'Gadi' (throne)." This period, though short-lived, had a lasting impact on the region and remains an important chapter in Kolhapur's political history.

Shirol and the Inaami Village

Around 35 km from Kolhapur lies Shirol Taluka, a village that became an important symbol of Maratha loyalty and honor. Known colloquially as “Inaami Village,” the term “Inaami” refers to something awarded as a gift or a reward. This reflects the village’s significant role in the Maratha struggle, particularly in supporting Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj during his reign, and later Maharani Tarabai after Shivaji Maharaj’s death.

The residents of Shirol demonstrated unwavering support for the Kolhapur branch of the Maratha Empire, particularly Tarabai and her son, Shivaji II. Recognizing their steadfast loyalty, Maharani Tarabai conferred upon the village the honor of being an “Inaami village,” solidifying its place in the history of the Kolhapur Sansthan (state). The village, which had become a key center of administration and military support, was entrusted with significant responsibilities during Tarabai’s regency.

In recognition of the support from the people of Shirol, Maharani Tarabai decided to establish a Takht, a symbolic throne, in the village. Initially used for housing and training horses, the Takht was later transformed into a monument of historical significance. The Takht is a stunning example of Maratha-style architecture, adorned with intricate carvings. The site comes alive during the Dussehra festival, which is celebrated here with immense enthusiasm.

This Takht, in many ways, stands as a reminder of the Maratha leadership, their valor, and the pivotal role that both Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and Maharani Tarabai played in shaping the destiny of the Maratha Empire.

ISKCON Mandir

Located near the serene Rankala Lake in Kolhapur’s Shivaji Peth, the ISKCON Mandir offers a peaceful retreat for devotees seeking spiritual solace. Established in 1991 by local followers of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), this mandir is part of a global movement founded by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prabhupada. Srila Prabhupada, at the age of 68, ventured to the West to spread the teachings of Krishna consciousness. In 1966, he formally established ISKCON, and over the years, traveled extensively to spread the teachings of Bhagwan Krishna.

The ISKCON Mandir in Kolhapur, located near the iconic Mahalakshmi Mandir, has become a cornerstone of spiritual practice for the local community. The mandir follows the teachings of Srila Prabhupada and is managed by the Governing Body Commission (GBC) based in Mayapur, West Bengal. As with other ISKCON mandirs, it is deeply involved in community outreach and cultural celebrations, most notably the annual Rath Yatra procession.

The ISKCON Mandir also runs several service- and education-based initiatives, including the Niyami Fun School (NFS), an educational program for children that focuses on imparting cultural values and spiritual teachings. The mandir organizes various programs, such as Satsang, Atmasakshatkar (a journey of self-discovery), and the Prerna and Chetana Yuvak-Yuvati Mahotsav, which offer guidance to the youth in their personal and spiritual development.

Jahaj Mandir

Located in Kumbhoj, approximately 29 km from Kolhapur railway station, Jahaj Mandir is a remarkable Jain temple renowned for its distinctive architecture. Often referred to as the ‘Ship Mandir’ by locals, the temple’s unique ship-shaped base has become a key feature that attracts visitors, showcasing the creativity and ingenuity of its builders.

Surrounded by well-maintained gardens on all four sides, the mandir is enveloped by a vibrant display of exotic flowers and shrubs. The gardens also feature intricately shaped topiaries of deities, adding an enchanting touch to the overall experience.

Inside the ship-shaped structure, visitors will find a grand museum and another smaller temple, both offering a deeper understanding of the mandir’s religious and cultural significance. The Jahaj Mandir becomes a focal point of celebration each year, drawing large crowds during the annual fair held on Kartik Poornima.

Adding to the temple’s mystique is a natural formation about 200 meters away from the structure, resembling a serpent standing about five feet tall. Local lore speaks of two living snakes believed to reside within this formation. It is said that these snakes emerge in the evening, returning to their resting place by night. Devotees believe that tying a coconut and cloth to the formation after completing three circumambulations will grant their deepest wishes, bringing blessings to themselves and future generations.

Jyotiba Mandir

Jyotiba Mandir stands as one of the most significant religious sites for the local community, with many families across Kolhapur considering it their kul devta, as noted in an article in Sakaal. Founded in 1730 by Ranoji Shinde, the founder of the Scindia dynasty, the mandir's white steeple rises to a height of 77 ft. According to the Kolhapur Gazetteer (1960), the temple is one of only two Jyotiba mandirs in Kolhapur, and local belief suggests that the worship of Jyotiba may be a practice unique to Maharashtra.

The main mandir houses the murtis of Jyotiba, along with the Devis Emaai and Choprai, who are also worshipped here. Surrounding the main mandir are smaller temples dedicated to Kedareshwar and Ram, each adding to the spiritual significance of the site.

The hill where the mandir stands, historically known as Kopad, has long been regarded as sacred for centuries. According to local legends, its importance is connected to Ambabai (also known as Mahalakshmi) of Kolhapur. One legend tells that Ambabai, troubled by rakshas and asurs, sought refuge in the Himalayas and prayed to Kedareshvar to defeat them. In response, Kedareshvar is said to have descended to Jyotiba Hill, bringing with him the Kedar ling, a symbol of Bhagwan Shiva, as noted in the Kolhapur Gazetteer (1960).

Another popular legend ties the hill’s sanctity to the battle between Jyotiba and the Rakshasas, led by their king Ratnasur. As the story goes, Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva transformed into Jyotiba to defeat the demon, ending his reign of terror. According to the gazetteer, with Ratnasur’s defeat, peace was restored, and the area was named Ratnagiri in honor of this victory.

The Chaitra Poornima festival, held annually at the mandir, is a significant event that attracts devotees from near and far. During this celebration, pilgrims bring long sticks, known as sasans, and throw colored powder, or gulaal, into the air, turning the mandir’s white walls a vibrant pink. The origins of this ritual are not entirely known, but it is said to be the reason the mandir has earned the local nickname of the “Pink Temple.”

Along with the Chaitra Poornima festival, the mandir also hosts a major fair to commemorate Jyotiba's victory over Ratnasur. The highlight of the fair is the annual marriage ceremony between Jyotiba and Yamai, as mentioned in the gazetteer. During the ritual, a brass image of Jyotiba is carried with great fanfare to the Yamai Mandir, where marriage rites are performed, including the placing of a seal (shikka) and a dagger (katar) between the two deities, symbolizing their union.

Kopeshwar Mandir, Khidrapur

While Kolhapur is famous for its well-visited Ambabai and Jyotiba Mandirs, there exists another treasure within its district, one that is a World Heritage site and often dubbed by many as the “Khajuraho of Maharashtra.” Nestled at the border of Maharashtra and Karnataka in Khidrapur taluka, the Kopeshwar Mandir is a masterpiece of ancient Indian architecture, though it remains relatively obscure and difficult to access via public transport. The mandir is under the supervision of the Archaeological Survey of India, which oversees its preservation.

Epic Connections

The Kopeshwar Mandir is unique for its dual representation of Bhagwan Shiva and Bhagwan Vishnu as lingas, a rare feature in Hindu mandirs. What makes this mandir even more remarkable is the absence of Nandi, the sacred bull usually found in Shiva mandirs. According to a Times of India (2017) article, legend has it that Lord Shiva became furious when Sati, an incarnation of Parvati, sacrificed herself by jumping into the sacrificial fire at her father Daksha's Yajna. To calm his anger, Bhagwan Vishnu intervened, bringing Shiva to the mandir. This event is believed to have led to the mandir being called Kopeshwar, which translates to "furious god."

The absence of Nandi here is intriguing. According to local legend, the Nandi associated with the Kopeshwar linga is located 12 km away in Yadur village, Karnataka. The story goes that Shiva and Parvati were excluded from a Yajna in Yadur, which angered Parvati. She attended the Yajna alone, accompanied only by Nandi, while Shiva remained at the mandir. Interestingly, the Nandi statue in Yadur faces west, while the mandir itself faces east, an arrangement that sets this mandir apart from others.

The Construction of the Mandir and its Legends

The history behind the construction of Kopeshwar Mandir is steeped in mystery and legend. Located in Khidrapur, which was historically known as Kopad, the mandir’s origins are surrounded by intrigue. Some stories even claim that the mandir was built in a single night, adding an aura of mystique to its construction.

One prominent legend traces the mandir’s foundation to 609 CE, when Chalukyan King Pulakeshi II initiated its construction as a symbol of prosperity for his kingdom. However, the project was abruptly halted due to the war between the Chalukyas and the Pallavas. Construction is believed to have come to an indefinite standstill after King Pulakeshin II was killed in battle.

It is said that it wasn’t until 1214 CE, under the reign of King Singhanadev of the Yadav dynasty, that the mandir was finally completed. In her article Khidrapur Kopeshwar Mandir: Poetry Carved in Stone, Yogita Khandge notes that early references to the mandir can be found in inscriptions from 1077 CE in Yelur, further validating the long history of the structure. However, some researchers also attribute the mandir’s creation to King Gandaraditya of the Shilharas in the 12th century, who is believed to have built it along the banks of the Krishna River.

Architectural Features

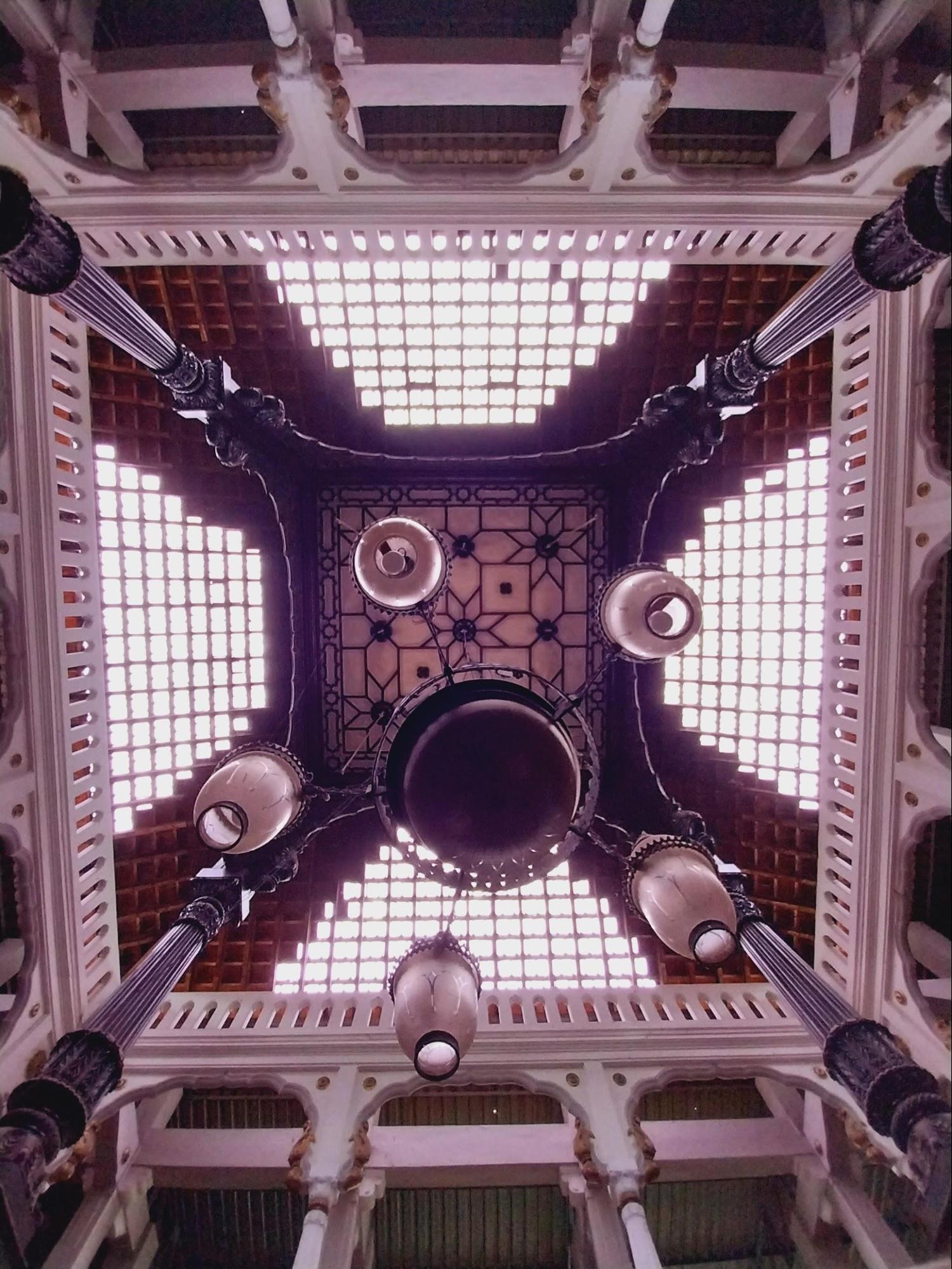

Despite its rich history and legends, the Kopeshwar Mandir stands as a remarkable feat of ancient architecture. Upon entering the mandir, visitors are greeted by the Swarga Mandap, a grand hall supported by 48 intricately carved pillars. The first row consists of circular pillars, followed by 16 pillars in the second row, 12 in the third, and 8 in the fourth, with two pillars at each of the four doors. These pillars depict a variety of devis and devtas (referred to as the Digpals) such as Yama in the south, Varuna in the west, Kubera in the north, Vishnu riding Garuda, Shankar on Nandi (Ishan), and Kartikeya on a peacock.

The mandir features three main doors, each leading into the sanctum, where beautifully carved idols and two prominent lingas are housed. The smaller linga, known as Kopeshwar, represents Lord Shiva (Mahadeva), while the larger linga, Dopeshwar, symbolizes Lord Vishnu. Additionally, the mandir premises house 12 shilalekhs (stone inscriptions), one of which is a donation from the emperor of the Yadava king, inscribed in Sanskrit.

The mandir stands on a foundation adorned with 92 intricate elephant carvings, and inside, 108 beautifully carved stone pillars elevate its grandeur. The mandir is divided into four sections: the Swarga Mandap (hall of heavens), Sabha Mandap (assembly hall), Antaral Kaksha (intermediate hall), and Garbha Griha (sanctum sanctorum). The Swarga Mandap features 48 pillars, each carved into distinctive geometric shapes, squares, hexagons, and octagons. Below the Swarga Mandap, 24 elephants form the Gaja Patta, while above this lies the Nara Patta, showcasing sculptures of dancers adorned with jewelry.

The roof of the mandir has a circular opening designed to allow smoke to escape during yagnas. Devotees believe this open ceiling invites divine presence from the heavens. The underside of the ceiling is made from Rangshila, a rare black stone not found locally, suggesting it was either transported from South India or, as per some locals, brought here by divine intervention.

As mentioned above, the assembly hall of the temple is adorned with 12 sculpted elephants mounted on gajapatta (elephant bases). Interestingly, the trunks of these elephants have been deliberately damaged, with some attributing the destruction to Aurangzeb.

Interestingly, the Kopeshwar Mandir is also known for a captivating natural phenomenon. During the first week of May, the sun’s rays shine directly into the Gabhara (sanctum), bathing the lingas in a spectacular display of light. This annual event draws attention to the mandir's cosmic and spiritual significance, making it an even more enchanting place of worship.

Adding to the mandir’s aura of mystery, the surrounding area is steeped in local legends. One such belief suggests that those who live near the mandir are cursed, unable to enjoy a happy married life.

Festivals & Rituals

In the summer months, a unique ritual called Butti Puja in Kannada and Dahi Bhaat Puja in Marathi takes place at the mandir. In this ritual, a mixture of rice and curd (dahi bhaat) is applied to the Shivling.

Every year, in January and February, a grand fair is held at the mandir, attracting thousands of visitors. Despite challenges in its upkeep, Kopeshwar Mandir stands as a testament to the artistic and spiritual grandeur of Maharashtra’s past, quietly awaiting further recognition for its historical and cultural significance.

Kukuteshwar Mandir

Nestled near the Town Hall, the Kukuteshwar Mahadev Mandir was established in 1941, when Rajaram III, the son of Shahu Maharaj, served as the ‘Shah Sarkar of Kolhapur’. The mandir is known for its unique features, including a tortoise at the entrance, symbolizing one of Vishnu’s ten avatars.

Located within the Town Hall area, the mandir is visited by a large number of people daily. Regular pujas are performed, typically early in the mornings and again in the afternoon.

One of the grandest celebrations held here is Mahashivratri, marked by vibrant festivities. On this auspicious day, devotees offer milk and food to Bhagwan Shiv, and some observe fasting as a mark of devotion. The day after the festival is equally significant; visitors bring offerings of masala bhat and vegetables, which are then distributed among fellow devotees as part of a communal meal.

Laxmi Vilas Palace

Kolhapur’s royal family has left a profound legacy across generations, each ruler shaping the region in their unique way. Several sites connected to this legacy offer a fascinating glimpse into the political and cultural history of the time. Among these, Laxmi Vilas Palace stands out, closely linked to one of Kolhapur’s most iconic rulers, Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj. Situated in the picturesque Kagalwadi, just 6 km from Kolhapur city, this palace has borne witness to the remarkable journey of Shahu Maharaj.

A progressive leader and social reformer, his reign not only transformed the princely state of Kolhapur but also made a lasting impact on India’s history. Revered as the "First Maharaja of the Princely State of Kolhapur," Shahu Maharaj is remembered for his progressive policies that championed equality, education, and social upliftment. His reign, occurring alongside the British expansion in Kolhapur, marked a pivotal chapter in the region’s history.

Laxmi Vilas Palace holds immense personal significance for Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, not only as his birthplace but also as a place of emotional connection throughout his life. It is said that even after ascending the throne, the palace remained a retreat for the ruler, where he often sought peace and tranquility, taking afternoon naps in its serene surroundings. The palace also housed a camp for his horses, situated at nearby Sontale, with a direct entrance linking the two.

Shahu Maharaj’s ties to Laxmi Vilas Palace are deeply rooted in his early life. Born to Jaysingrao Ghatge, a prominent Sardar in the Kolhapur Sanstha, Shahu was adopted by the royal family at the age of 10, an event that altered the course of his life. Despite this new status, he had no legal claim to Laxmi Vilas Palace. In order to resolve this, Shahu Maharaj arranged with his father, exchanging the palace for the old Municipal Corporation building.

After he died in 1922, Shahu Maharaj’s successor, locals state that Chhatrapati Rajaram Maharaj, took up the responsibility of preserving and maintaining the palace, ensuring its historical significance was upheld well into the post-independence era.

Post-Independence Role and Preservation

In the years following India’s independence, Laxmi Vilas Palace was designated as a Circuit House by the government, hosting visiting dignitaries and politicians, including Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. In 1974, recognizing its historical importance, the government declared the palace a protected monument, ceasing its use as a guesthouse. By 1977, the palace came under the jurisdiction of the State Archaeology Department of Maharashtra, ensuring its preservation for future generations.

Constructed from white clay bricks (पांढऱ्या मातीच्या विटा), the palace was renovated using mesh and plaster to maintain its structural integrity. This renovation, overseen by the Archaeology Department, ensured that the original walls and aesthetic were preserved, while securing the building’s durability for years to come.

As part of its cultural preservation efforts, it is said that the Archaeology Department of Maharashtra is planning to transform part of the Laxmi Vilas Palace into a museum dedicated to Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj. This museum will honor his enduring legacy, with exhibits highlighting his life’s work and contributions. A Samadhi (memorial) will also be included, providing the public with an opportunity to pay their respects.

One of the key exhibits will feature a miniature replica of the Radhanagari Dam, a monumental project initiated by Shahu Maharaj to provide irrigation and water supply to the region. Additionally, the museum is expected to house a stone gallery displaying intricate carvings collected from various locations across Maharashtra, offering a glimpse into the state’s rich cultural and artistic heritage.

Mahalakshmi Mandir

Nestled along the banks of the Panchganga River in Kolhapur, the Mahalakshmi Mandir stands as one of the most significant religious sites in Western India. Revered as one of the 51 Shakti Peethas, this historic mandir, dedicated to Mahalaxmi Devi, is a cultural landmark that attracts thousands of yatris every year.

Historical and Cultural Significance

Kolhapur, historically known as Karvir, has long been a center of religious and trade activity in the region. The Mahalaxmi Mandir holds a special place in the hearts of millions, with the goddess herself being the kul devi (family goddess) of many communities across Maharashtra. The mandir's legend is deeply entwined with the speculated origins of the district itself, lending it an additional layer of historical and spiritual importance.

One of the most famous local legends is that of the rakshas Kolhasur, after whom the city is named. According to the legend, Kolhasur wreaked havoc on the land, causing untold suffering. In response, Mahalakshmi, incarnated as Ambabai, descended to Earth to rid the region of the rakshas’s tyranny. After a fierce battle, she defeated him, and in his dying breath, Kolhasur requested that the place be named after him. The Devi granted this final wish, and thus the name Kolhapur is said to have come into existence. In this story, Ambabai is not only a vanquisher of evil but the eternal protector of Kolhapur, ensuring its prosperity and peace.

Another popular alternative legend explains why Mahalakshmi Devi is believed to reside in Kolhapur. According to the legend, Rishi Bhrigu, one of the seven great sages (saptarishis), visited Vaikuntha, the heavenly abode of Bhagwan Vishnu. However, when Vishnu failed to greet the sage properly, Bhrigu became enraged and attacked him. Despite the assault, Bhagwan Vishnu responded with humility, showing no anger. Witnessing this, Devi Lakshmi became upset, feeling that her lord had been wronged. In response, she left Vaikuntha and descended to Earth, choosing Kolhapur as her new home. To this day, devotees believe that Mahalakshmi blesses them with prosperity and protection from this very location.

The legend also explains why, in Hindu tradition, the blessings of Mahalakshmi are considered incomplete without those of Bhagwan Tirupati. As a result, every year on Dussehra, a silk saree is sent from Tirupati to Ambabai in Kolhapur, an action that symbolizes their deep connection.

Historical and Architectural Features

The Mahalakshmi Mandir stands as a marvel of medieval architecture, combining functional design with spiritual symbolism. Constructed around 700 CE during the Chalukyan era, the mandir is a fine example of the Hemadpanthi architectural style, which flourished in the Deccan region. Characterized by mortarless construction, this technique involves large, precisely cut stone blocks fitting together with remarkable precision, creating structures that have endured the ravages of time. The mandir is primarily built from black stone, sourced from nearby quarries, giving it a striking, timeless appearance. This use of local material not only enhances the mandir’s beauty but also connects it to the surrounding landscape.

While the Hemadpanthi style dominates the mandir’s structure, some historical accounts suggest that the site may have origins even older than the Chalukyan period. According to the Gazetteer of Kolhapur (1960), there are claims that the mandir was originally a Jain shrine, dedicated to Padmavati, the Jain goddess, before it was later adapted for Brahmanic worship. This transformation reflects the evolving religious dynamics of the region, adding layers of historical complexity to the mandir’s legacy.

The mandir’s history is also intertwined with the political upheavals of the region. During the 14th and 15th centuries, when the mandir faced threats of destruction, the murti of Ambabai was hidden for its safety. It was Sambhaji Maharaj, the Maratha ruler and son of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, who ensured the murti’s return to the mandir in 1722.

Festivals and Rituals

The Mahalakshmi Mandir comes alive during festivals like Navratri, when the devi is adorned with jewels and the mandir is illuminated with thousands of lights.

Pilgrims from all over the country gather during this time to participate in the grand celebrations. Another significant ritual is the Raksha Dhaga Pooja, which takes place during Holi. In this ritual, married women tie sacred threads around a banyan tree, symbolizing protection and devotion, particularly towards their husbands.

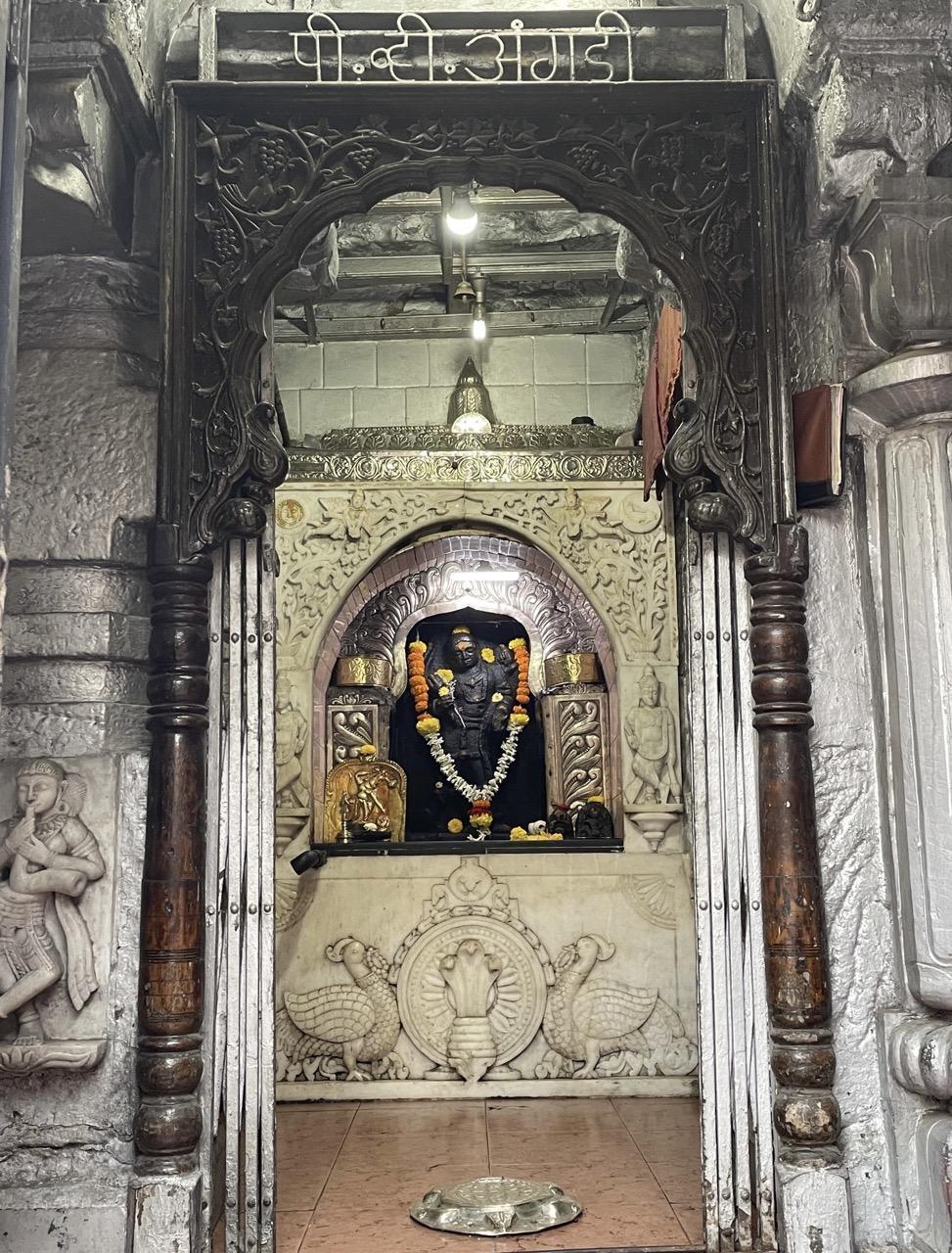

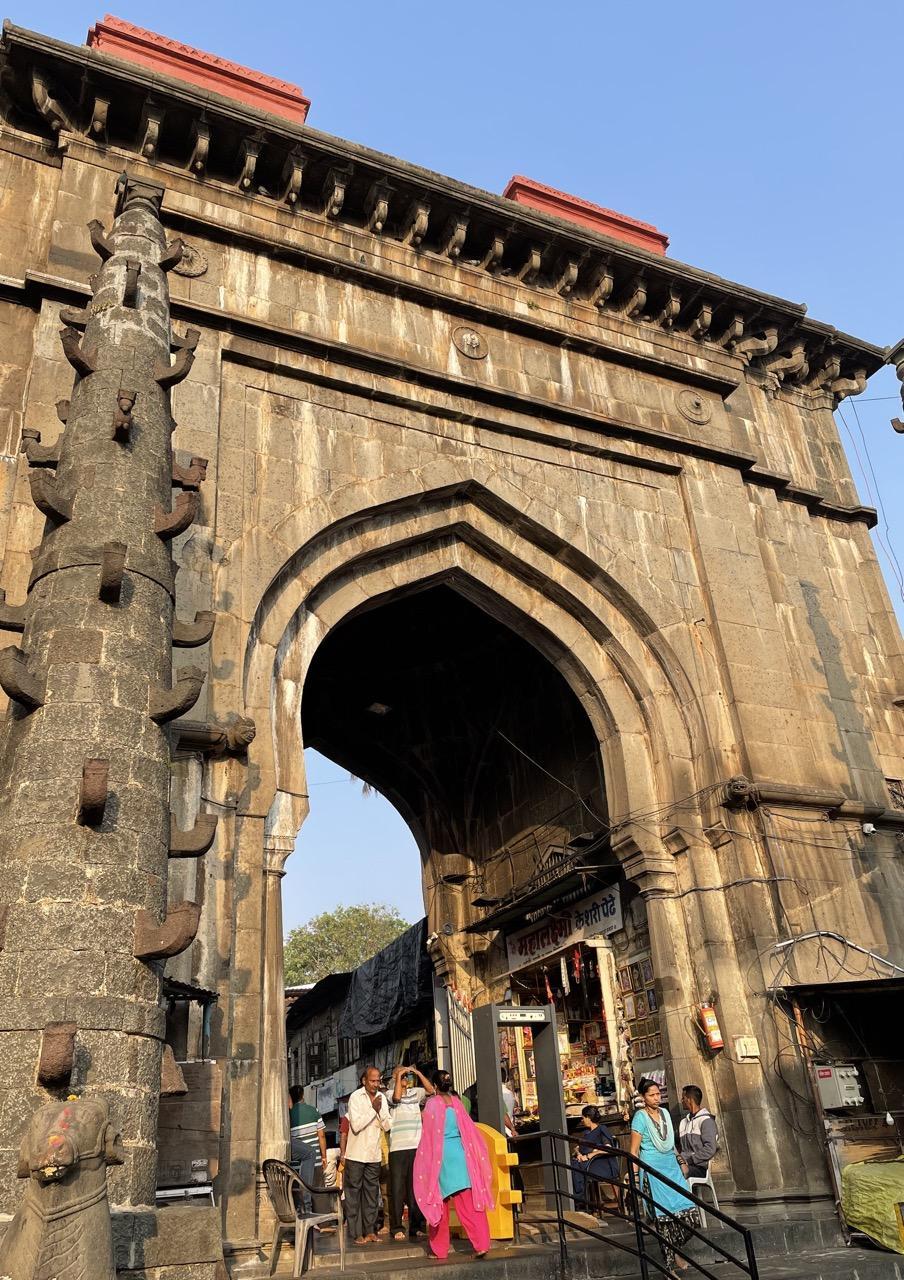

Nagarkhana

Nearby, another historic structure, Nagarkhana, serves as a reminder of the city’s royal past and its historical significance. While many locals pass by Bhavani Mandap without a second glance, few realize that just a short stroll away, Nagarkhana, a magnificent structure built by Chhatrapati Shahaji (also known as Bhuvasaheb Maharaj), was once the grand entrance to the royal palace. Shahaji ruled Kolhapur from 1822 to 1838, and commissioned this stunning edifice, which remains an architectural marvel today.

Before the British arrived in Kolhapur, Nagarkhana was not only the gateway to the royal palace but also, as noted in the Gazetteer of the time (1886), “perhaps the tallest building in the city.” With the onset of British rule and Kolhapur’s transformation into a princely state, Nagarkhana took on a new significance. Locals recall how the saffron flag of Swarajya flew proudly from its rooftop, symbolizing Kolhapur’s sovereignty during the colonial rule.

The construction of the building itself is equally remarkable. It is said that the Nagarkhana was built using stones sourced from Jyotiba Hill and Patharwat in North India, hinting at the scale and vision behind its creation.

Interestingly, the building’s name, Nagarkhana, is derived from Nagars, traditional drums that once reverberated through its halls during royal events and celebrations. Today, a memorial pillar dedicated to Olympic hero Khashaba Jadhav stands proudly outside the building, while a murti of Shri Ganaraya and a clock greet visitors at the entrance, adding to the charm of this historic site.

However, as some locals note, the name Nagarkhana is no longer commonly used. The gateway is now mostly referred to as Bhavani Mandap, a name that has come to be associated with the entrance to the Mahalakshmi Mandir. While still part of the mandir complex, Nagarkhana’s original identity has been somewhat overshadowed. Efforts are reportedly underway to restore its historical name and bring attention to the rich legacy of this once grand entrance to the royal palace.

Narsoba Chi Wadi Mandir

Narsoba Chi Wadi Mandir, commonly referred to as Narsobawadi Mandir, is situated at the confluence of the Krishna and Panchganga rivers in Shirol, a village located in Kolhapur. The mandir is devoted to Guru Nrusinha Saraswati, who is recognized as the second incarnation of Bhagwan Dattatreya, a significant deity within the Datta sect of Hinduism. The structure is of historical and cultural importance, both for its association with the religious practices of the Datta tradition and its architectural legacy.

Founding and History

The construction of Narsoba Chi Wadi Mandir is believed to have occurred between 1378 CE and 1458 CE. Uniquely, unlike many other mandirs dedicated to Bhagwan Dattatreya, this mandir does not feature statues or idols of Narasimha Saraswati Swami. Instead, the divine presence of Narasimha Saraswati Swami is symbolized by a pair of sandals, or padukas, enshrined within the mandir.

The mandir is deeply connected to the worship of Bhagwan Dattatreya, particularly through the incarnation of Narasimha Saraswati Swami, considered to be the second avatar of Bhagwan Dattatreya. According to local lore, Narasimha Saraswati Swami spent a significant part of his life meditating and performing divine work in this area. This region, known as Nrusinhawadi, is regarded as a karmabhumi (place of divine work) for the Swami, where numerous sages and saints are believed to have visited or meditated.

In addition to this, the mandir is linked to the story of Tembe Swami, another incarnation of Bhagwan Dattatreya, who is said to have lived in this area for twelve years. The room where Tembe Swami is believed to have resided contains the padukas of Bhagwan Dattatreya.

The foundation story of the mandir not only ties to spiritual figures but also involves political figures. According to local tradition, Adilshah, the Sultan of Bijapur, commissioned the construction of the mandir in gratitude after his prayer for the restoration of sight to his blind daughters was answered.

Rituals and Practices

The religious rituals at Narsoba Chi Wadi Mandir are deeply embedded in the mandir’s daily operations. These rituals include the Paduka Pooja and Kakad Aarti, which take place at 5:00 am. In the late morning, from 8:00 am to 12:00 pm, the mandir performs the Rudrabhishek, a form of worship dedicated to Bhagwan Shiva. Following this, the Maha Aarti takes place, which is one of the central devotional activities of the mandir. The evening is marked by Dhoop Aarti at 7:30 pm, and the day concludes with the Shej Aarti at 10:00 pm.

Additionally, the mandir conducts a range of important religious observances, with Mahapuja being performed during every Poornima (full moon), as well as during Gurupoornima, Datta Jayanti, Mahashivratri, and Narli Poornima. These events draw large numbers of devotees, underscoring the mandir's role as a vital center of faith for the surrounding region.

Panhala Fort

Nestled in the lush green hills of the Sahyadri Range, Panhala Fort is often regarded as one of the most historically significant forts in Maharashtra. Its rich history, spanning several centuries, has seen it witness numerous dynastic shifts, military engagements, and cultural exchanges. The fort sits atop a hill that offers a commanding view of the surrounding plains, adding to its strategic importance. As noted in the Kolhapur Gazetteer (1886), “The Panhala uplands are 2772 feet above sea level and about 1300 ft. above the Kolhapur plain, and the hilltop, which the Panhala fort crowns, rises about 275 feet above the uplands.”

![A panoramic view of Panhala Fort, showcasing its strategic location and defensive structures that have withstood centuries of history and conflict.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/cultural-sites/a-panoramic-view-of-panhala-fort-show_Y7D74TD.png)

Etymology and Nomenclature

The name “Panhala” carries with it layers of history and intrigue. Like many forts, its designation has changed over time. A historical reference from the Kolhapur Puran (circa 1730) records the fort as Pannagalaya, a term likely preceding the commonly used Panhala. The word “Panhala” is traditionally believed to be derived from the Sanskrit words Pannag (meaning “King Cobra”) and Aalay (meaning “house”), which together translate to “The Land of King Cobra.” It’s possible that Panhala emerged as a later, phonetically altered version of the original compound word.

Fascinatingly, this name seems to reflect not only the fort’s natural surroundings but also its distinctive, serpentine-like structure, which, in turn, added to the fort’s distinctness. The fort’s winding paths and layered fortifications evoke the image of a coiled cobra, adding an interesting layer to its etymology. Additionally, the gazetteer mentions that inscriptions from earlier periods also feature variations of the name, such as Pranlak and Padmanal, each providing a glimpse into the evolution of the fort’s nomenclature across centuries.

The Fort's Early History and Cultural Legacy

Forts have long stood as historical pivots, marking the battles, victories, and shifting power dynamics that shaped the course of civilizations. Panhala Fort, in particular, encapsulates this rich, tumultuous history, highlighting its immense significance in the region’s past.

It is said that Panhala was an integral part of trade routes that connected the Deccan plateau to the Arabian Sea. This strategic and commercial importance likely contributed to why various dynasties coveted control over the region.

Scholars Patil and Sabale, delving into the fort and its surrounding area’s historical significance, explain, “From 1st Century CE to 1050 CE, Panhala was under the rule of different dynasties such as Satavahan, Andrabrutya, Kadambas, Rashtrakutas, and Western Chalukyas, but the hills around the fort were fortified by walls during the period of Shilahara King Bhoj II in 1191 CE.” It is said that the legacy of the Shilahara dynasty endures in Panhala, with the engravings of lotuses on its structures serving as one of the few surviving traces of their rule.

The Influence of the Bahmani and Adilshahi Dynasties

After the Shilaharas, Panhala came under the control of various dynasties, notably the Yadavas, before falling into the hands of the Bahmani Sultanate in the 14th century. This period marked a phase of significant architectural and military developments at the fort. As the Bahmani Sultanate expanded across the Deccan Plateau and along the western coast, Panhala became an integral part of their defense network. The fort’s location at a strategic highland made it an ideal outpost for military operations and a key focal point for the Sultanate's territorial ambitions.

The cultural landscape of the fort also evolved during this time. The arrival of Sufi mystics and saints, who found refuge in Panhala, left a lasting imprint on the spiritual and cultural life of the region. Among the most revered figures was Hazrat Pir Shahduddin Baba, a prominent 14th-century Sufi saint, whose tomb still stands within the fort, reflecting the deep spiritual history of Panhala.

Strategic Importance and Maratha Influence

Panhala gained further prominence in the Maratha period, particularly under the leadership of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. According to scholars, on 28 November 1659, Shivaji Maharaj first entered Panhala, and he was greatly impressed by its expansive grounds, the large grain storage facilities, and its formidable fortifications. Scholars note that Shivaji's admiration for Panhala’s strategic advantages led to further strengthening of the fort's defenses, including the construction of additional protective walls, colloquially called Pad-Kote, to safeguard the fortress.

Panhala was not only a military stronghold but also a center of administration and governance. The fort’s wide plane surface, coupled with its huge gateways and ancient water resources, made it an ideal location for organizing military campaigns and managing the region. During Shivaji's reign, Panhala played a central role in the defense of his newly established “Swarajya.” The fort's pivotal role during the battles of the 1670s, particularly the battle for control of Panhala, underlines its importance to Maratha military strategy. The Gazetteer (1886) provides insight into the turbulent history of the fort, noting that “in May 1660, to reclaim Panhala from Shivaji, Ali Adil Shah II of Bijapur dispatched Sidi Johar, who laid siege to the fort, where Shivaji had taken refuge. After four months of siege, Shivaji managed to escape to Rangana, about fifty-five miles southwest of Kolhapur, and soon after, Panhala and Pavanagad were retaken by Ali Adil Shah himself.” Despite such setbacks, the fort remained firmly in the Maratha camp following Shivaji's reconquest in 1673, a position it retained until he died in 1680.

The Later Years and Decline

The early 18th century saw significant changes in the fate of Panhala, particularly following the death of Rajaram Maharaj in 1700. The Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, seeking to subdue the Marathas, launched a campaign to capture Panhala in 1701. As noted in the District Gazetteer (1960), “In 1692, Panhala was retaken by Parasuram Trimbak, the ancestor of the Kolhapur Pant Pratinidhi family of Visalgad. In 1701, the emperor Aurangzeb laid siege to and took Panhala in person.”

The Mughal forces were initially successful in their efforts; however, this victory was short-lived. It is noted in the gazetteer that, “Shortly after, in 1701, Panhala was taken from the Mughals by Ramcandra Pant Amatya.” Despite the Mughals’ initial success, the fort was once again claimed by the Marathas.

Following Rajaram’s death, his widow Tarabai made Panhala her headquarters in 1705, continuing the struggle for Maratha sovereignty. The District Gazetteer further details the ongoing conflict, stating: “In Tarabai’s war with Sahu of Satara in 1708, Sahu took Panhala and Tarabai fled to Malvan in Ratnagiri. Shortly after, in 1709, Tarabai again took Panhala.”

The fort continued to play a role in regional conflicts well into the 19th century. In 1844, during the colonial period, the East India Company attacked Panhala under the command of General Delemonte to quell the rebellion of the Kolhapur State. The artillery attack led to the destruction of the fort’s eastern gateway, known as Char Darwaja (Four Doored Gate).

Architectural Significance

While Panhala Fort is widely celebrated for its military legacy, its architectural brilliance deserves equal recognition. The fort’s design is not merely about defense; it speaks volumes about its strategic significance and its role as a thriving center for both military operations and daily life.

Beyond its historical role as a fortress, Panhala’s structures reflect a thoughtful blend of planning and craftsmanship. These buildings offer a window into the fort’s rich political history, revealing the interplay of power and strategy, while also capturing the lived experiences of those who called the fort home. Each building within the fort reflects the vision of its creators, making Panhala Fort not only a stronghold of defense but also a vivid reflection of the life and stories that unfolded within its walls.

Darugola Kothar

The 'Darugola Kothar,' also called the 'Darukhana,' was an essential structure within the fort, designed with one clear purpose: to store ammunition. The name itself says it all: 'darugola' translates to ammunition or powder in Marathi. At a time when cannons (toafs) were vital to warfare, this secure storage became crucial for the fort's defense.

The location of the building appears to have been carefully considered, perhaps to offer protection from enemy cannon fire, particularly from the lower embankments. Additionally, its isolation, surrounded by open space, may have been a deliberate choice, possibly intended to ensure clear sightlines for soldiers stationed around the perimeter, enhancing surveillance. This separation might have also made it harder for enemies to approach the Kothar unnoticed.

Ambarkhana

One of the most significant structures often highlighted by historians when discussing Panhala Fort is the Ambarkhana, occasionally referred to as Dhanyakothar. The Ambarkhana was primarily a granary, a place where essential food grains were stored to sustain the fort's inhabitants during prolonged sieges and periods of conflict. Among the fort's key structures, three massive grain storage buildings, named Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati which stand out for both their scale and architectural resilience.

Local historians suggest that these granaries may have stored as much as 25,000 khandi of grain (with 1 khandi equaling 20 sacks). Grains such as rice, nagli, and vari are believed to have been kept here. The Ganga Kothi, the largest granary, is said to cover 10,200 square feet and rise to a height of 35 ft. Each granary is said to have been designed with openings for ventilation and light, possibly to ensure the preservation of the grain. Built to withstand the test of time, these structures seem to have played a significant role in the fort’s overall functionality.

Next to the granaries, there was an underground warehouse that likely stored weapons, along with a minting facility where silver coins may have been produced. The fort’s defenses were also reinforced by a large rampart and a trench, reportedly 9 feet wide and 10 feet deep, designed to limit direct access by enemies.

During the siege by Siddi Jauhar, it is said that the grain in Ambarkhana helped sustain the fort’s soldiers, elephants, and horses for as long as fourteen months. When supplies began to run low, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj is believed to have decided to march to Vishalgad on 12 July 1660. The Ambarkhana, with its considerable grain storage, most likely played an important role in the fort’s ability to endure such a long siege.

Dharma Kothi

Dharma Kothi, a historical structure within Panhala Fort, is often admired for its unique architectural style. Measuring 55 feet in length, 48 feet in width, and 35 ft. in height, it contains three rooms, with the main hall featuring carved figures that resemble natural paintings. The building is square-shaped and made entirely from lime masonry, contributing to its lasting appeal.

A staircase leads to the roof, and the entrance is situated on the north side. The many windows are believed to provide good airflow, while a carving of Maruti can be found on the eastern wall. The area around the building is said to be surrounded by large Bakul trees.

Historically, it is said that Dharma Kothi was used to store grain from the Ambarkhana granaries, which was later donated to fakirs and the poor, a charitable practice that lends the building its name. Today, it serves as the office for the Panhala Police Station, with maintenance overseen by the Public Works Department. Nearby, a shop operated by the Panhala Municipality and a weekly market on Sundays further enliven the area. The Archaeology Department is responsible for the building's preservation.

Kalavantin Mahal

Kalavantin Mahal is a significant structure located at Panhala Fort, built by Ibrahim Adil Shah II during the 16th century. Situated on the eastern rampart of the fort, it was designed as a residence for thirty kalavantin (female performers), who entertained the court with their performances in dance and song. This architectural gem stands as a testament to the artistic patronage that flourished under Ibrahim’s reign, reflecting the fusion of culture and power in the Adil Shahi court.

Ibrahim Adil Shah II was one of Bijapur’s most celebrated rulers and was known for his deep commitment to art and culture. His reign marked a period of cultural renaissance, where poets, musicians, and artists were given royal support, and intellectual pursuits flourished. Scholar and the first curator of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, PK Gode (1956), regarded Ibrahim Adil Shah II as “one of the most cultured kings of Bijapur.” Nazir Ahmad further emphasizes the Sultan’s influence, noting that Ibrahim’s court was so revered that he earned the title Jagat Guru—a recognition not just of his political authority, but of his profound role as a mentor to the intellectuals and artists at his court.

Mark Zebrowski, a renowned scholar and historian of Islamic art, dubbed Ibrahim “the greatest patron of the arts the Deccan produced.” His legacy extended beyond patronage; he was a poet himself, authoring Kitab-i Nauras (Book of Nine Rasas), a collection of 59 poems and 17 couplets in Dakhani. This literary contribution highlights Ibrahim’s deep connection to art and his legacy as both a ruler and an artist. Kalavantin Mahal, though often overlooked, is a key piece of this cultural legacy. It offers a rare glimpse into an era when art was an integral part of court life and politics.

Pusati Buruj

At the western corners of Panhala Fort stands the Pusati Buruj, a strategically placed tower that once played a vital role in the fort’s defense. Constructed from black stone, the 20-foot tower was designed for surveillance, allowing defenders to keep a keen eye on the surrounding landscape, especially to the west, north, and south. Its elevated position ensured that any approaching enemy could be spotted early, offering crucial time to prepare for conflict.

As part of the fort's larger defense system, Pusati Buruj was accompanied by a deep moat, perhaps serving as both a defensive obstacle and a potential escape route. Today, the tower offers visitors a panoramic view of the surrounding Masai Plateau and nearby forests, highlighting its original military function. It is a window into both the fort’s tactical design and its historical significance as a watchtower.

Someshwar Mahadev Mandir

Nestled next to Someshwar Lake in Panhala is the Someshwar Mahadev Mandir, which stands as a place of both historical and religious importance. Legend has it that after returning from Pratapgad, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj offered a hundred thousand gold flowers at this very mandir through his mavlas (soldiers), a gesture that reflects his deep reverence for the devta.

The Someshwar Lake itself is an impressive feature, with a large reservoir believed to have been built during the rule of Adil Shah. Surrounded by stone structures, the lake is accessed by steps leading down to its water, which serves as a vital resource for agriculture, ensuring a steady supply of water throughout the year.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Mandir

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Mandir is a religious and cultural site that lies within the premises of the fort. Built in 1913 by Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, the mandir is dedicated to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and stands as a symbol of Maratha heritage and legacy within the Panhala region.

The mandir’s main attraction is a marble statue depicting Shivaji Maharaj on horseback, crafted by an artist from Kagal. Adjacent to the statue are the paduka (footprints) of Chhatrapati Tararani, the founder of Kolhapur (Karveer) State, acknowledging her important role in the region’s history.

Possibly what makes this site particularly unique is the presence of 22 ancient caves that lie behind the mandir. Dating back to around the 3rd century BCE, these caves predate most of the fort’s known history and offer insights into the region’s early cultural practices. Though these caves are now closed to the public, their presence adds historical depth to this shrine that honors Maharashtra’s most revered leader.

Parashar Guha

Perhaps, long before Panhala gained prominence for its fort and the dynasties that once ruled the land, it can be said that the region had already been a significant site of spiritual importance. The caves near the Chhatrapati Shivaji Mandir offer a glimpse into this past, and one of the most notable traces of this spiritual history is Parashar Guha, or Parashar Cave. Named after the revered Maharishi Parashar, who is credited with composing the Vishnu Purana, widely considered the first Purana, the cave stands as a reminder of the area’s ancient and spiritual legacy.

Amrit Verma writes in Forts of India (1985), “Panhala has a long history. It is said that the fort was the seat of the sage Parasar, whose rock-cut cave to the south can still be seen.” The cave, carved into the rock, is believed to have been the site where Sage Parashar meditated for long stretches, making it a place of deep reflection and spiritual significance.

The cave measures approximately 7 ft. in height, 8 ft. in width, and 40 ft. in length. The main room features a 6-foot deep space, designed for meditation. The cave is also historically significant for its association with Moropant (Moreshwar Ramchandra Paradkar), a Marathi poet known for writing 108 versions of the Ramayan. It is believed that Moropant composed some of his early works in this cave. Additionally, Siddeshwar Maharaj of Kolhapur is said to have sought refuge here.

The cave consists of two rooms, both furnished with seats made of stone. The first room is uniquely shaped like the mouth of a musical instrument, contributing to the cave's distinct atmosphere. Due to its tranquil setting, the cave remains relatively undisturbed by visitors.

Adjacent to Parashar Guha is the bungalow of Bharat Ratna Lata Mangeshkar. The cave is accessible via a road that leads to Pavangad, and the nearby Kolhapur air station tower is another landmark in the vicinity.

Wagh Darwaja

The northern gate of Panhala Fort, known as Wagh Darwaja (Tiger Gate), has a fitting name based on its historical purpose. A local saying goes that, as the tiger traps its prey, so did the enemy find themselves trapped upon entering through this gate. The name serves as a reminder of the fort’s strategic defenses, with the gate playing a key role in preventing escape during times of attack.

Teen Darwaja

The Teen Darwaja, also known as the Konkani Darwaja, is one of the most significant architectural features of Panhala Fort. This gateway holds historical and strategic importance as the only entrance to the fort from the west.

The structure of Teen Darwaja is particularly remarkable for its craftsmanship. The arch is adorned with intricate carvings of Sharabh, a mythical creature that combines the form of a tiger with wings. The entire structure, made of black stone, is carefully crafted with lead pouring and fine detailing.

In front of the Teen Darwaja, the central square features a well referred to as Vishnutirtha, which was constructed to provide drinking water to the soldiers stationed at the fort. This feature adds to the practical significance of the gateway, serving the needs of those who defended the fort.

The Teen Darwaja is also linked to a military event during which it is believed that Siddi Jauhar fired three cannons at the gateway.

The Teen Darwaja itself is a three-story building, with a staircase leading to the upper floors. On one of the towers, a Shilalekh (stone inscription) was placed by Subhedar Ambu-al-Saud, adding to the historical significance of the structure.

In the past, it was customary for the Teen Darwaja to be closed at sunset and opened only at sunrise, a practice that reinforced security and discipline within the fort. This rule was strictly followed, underscoring the importance of the gateway in the fort's daily operations.

Sajjakoti

Sajjakoti is a distinct site within the fort that was once the focal point for the political and administrative heart of the region. This distinguished one-story building, constructed in the early 16th century by Ibrahim Adil Shah of the Bijapur Sultanate, served as the site for critical discussions on governance, defense, and diplomacy. A space where strategic decisions were made and perhaps where the course of the kingdom’s future was often determined.

The name Sajjakoti, derived from the word ‘Sajja’ meaning ‘balcony,’ aptly describes the building’s architectural design, open balconies that provided both an expansive view of the surrounding valley and a strategic vantage point over key landmarks, such as Pavangad, Jyotiba Mandir, and Rankala Lake.

The building was originally used for administrative purposes, serving as a meeting place for high-ranking ministers and military leaders. Its elevated position on the fort allowed it to function both as a space for strategic discussions and as a lookout point, providing surveillance over the valley to monitor potential threats.

Sajjakoti is also historically significant due to its association with the Maratha Empire. According to the district Gazetteer (1960), Sambhaji Maharaj was “kept under guard by his father [Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj] at Panhala," and it is believed that this building may have been the location where he was confined during that time.

Today, Sajjakoti remains a notable landmark at Panhala Fort, attracting visitors who come to enjoy the scenic views from its rooftop and to reflect on its historical importance. The building continues to serve as a symbol of the fort's strategic role and its significance in the region's military and political history.

Chhatrapati Tararani Rajwada

The Chhatrapati Tararani Rajwada holds a significant place in the relatively more modern political history of Kolhapur. This palace, alongside the Panhala fort, is tied to a period of political upheaval in the Maratha Empire, following the deaths of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and his son, Sambhaji Maharaj, and the beginning of the newly founded Kolhapur State. The Maratha Empire faced power struggles after their deaths, and it was during this time that Rajaram, Shivaji’s second son, took up the mantle and ensured the continuity of the Maratha cause.

After Rajaram died in 1700, leadership was provided by his widow, Tarabai. Sumit Sarkar, in his book Issues in Modern Indian History (2000), states, “After Rajaram died in 1700, effective leadership was provided by his widow, and the Marathas remained unsubdued, gradually eroding Mughal control over Southern India.” Tarabai’s leadership played a crucial role in the Maratha resurgence, but she also became embroiled in a prolonged power struggle with Shahu of Satara. This conflict lasted nearly 24 years, and it was resolved, as Sarkar notes, “by the formation of a separate branch Kingdom at Kolhapur under the control of Rajaram’s lineage, while leaving the empire to Shahu and his hereditary chief ministers (The Peshwas)”

During the formative years of the Kolhapur Kingdom, Panhala became its administrative heart. The Gazetteer notes that in 1709, Tarabai once again took control of Panhala, which remained the seat of the Kolhapur government until it moved to Kolhapur itself in 1782. This period of 74 years marked Panhala’s significance as the administrative center of the kingdom.

At the core of the Kolhapur Kingdom’s early governance stood Queen Tarabai, who made Panhala her political base. The Rajwada, believed to have been constructed in 1708, was not only her residence but also the nerve center of the kingdom. As Amrit Verma (1985) states, “In 1705, Tarabai, the widow of Rajaram, made Panhala her headquarters.”

The architecture of the Rajwada is simple yet dignified. The two-story structure, with its stone stairs and guard rooms at the entrance, exudes a quiet strength. A large open square lies in front of the building, with the Panhala Vidyamandir school standing nearby.

Adjacent to the Rajwada lies the अग्गड (Agad), a ground built by Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj (1894-1922) for Sathmari, a traditional game involving challenging a tamed elephant.

Sathmari was an adventurous game where men trained in elephant handling would face off against a loose elephant. Popular in the Kolhapur and Baroda princely states during the 19th century, it was often showcased to guests, including English governors. The Agad, as locals say, was used as a training ground for these men. Alongside the Rajwada, these sites bring to life the key events and tales associated with the prominent figures of Kolhapur State at Panhala.

Chhatrapati Sambhaji II Mandir

The Chhatrapati Sambhaji II Mandir, tucked away within the Panhala Fort, remains a lesser-known but historically significant structure.

Sambhaji II (also known as Sambhaji I of Kolhapur) was the second Chhatrapati of Kolhapur (Karveer) State. He was the grandson of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and the son of Chhatrapati Rajaram Maharaj and his second wife, Rajasbai. Sambhaji II ascended the throne after a coup organized by his widowed mother against Tarabai and her son. His reign lasted from 1712 to 1760, marking a significant chapter in the region's history. After his death, it is said that his cremation took place in Kolhapur, on the banks of the Panchganga River.

Many locals state that it is the only one in Asia to have a buruj (watchtower). It is also believed that the structure was once a Yadava-era wada before being repurposed as a mandir. The mandir is said to have been built by Mahadevrao Subhanrao Dalvi, a Halwaldar of Panhala Fort.

Pant Amatya Bavdekar Wada

The Maratha Empire, renowned for its cultural, political, and military influence, has left an indelible mark on Kolhapur, visible through numerous monuments and landmarks spread across the region. While the royal family of Kolhapur stands at the center of this legacy, the contributions of influential families like the Amatyas are equally significant. Their history is intricately connected with Kolhapur and the Maratha Empire, and one of the key landmarks honoring their legacy is Pant Amatya Bavdekar Wada.

Believed to have been constructed between 1933 and 1935 by Parashuram Rao Amatya, the 9th descendant of Ramchandra Pant Amatya, the wada offers a glimpse into the political history of the region.

The Amatya family played a crucial role in the administration of the Maratha Empire, particularly under the reigns of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and his successors. The family is best known for its intellectual and diplomatic influence, with Ramchandra Pant Amatya (1650–1716) standing out as one of its most prominent figures. Serving as the Finance Minister (Amatya) on the Council of 8 (Ashta Pradhan) from 1674 to 1680, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was a key advisor to Shivaji Maharaj and had a significant hand in shaping the empire’s governance.

Ramchandra Pant Amatya’s influence extended far beyond his role in finance. It is said that he served under five successive Chhatrapatis, including Shivaji Maharaj, Sambhaji Maharaj, and Rajaram Maharaj, cementing his place as a crucial figure in the Maratha Empire. Ramchandra Pant is particularly noted for his involvement in the 1674 Rajyabhishek (coronation) of Shivaji Maharaj, during which he participated in the ritual of “Dadipurna Tamra Kalash.” This traditional act, performed by the Ashta Pradhan, was an important part of the coronation ceremony and highlighted the significant role the Amatya family played in the administration of the Maratha Empire.

In addition to his administrative role, Ramchandra Pant Amatya is believed to have authored the Adnyapatra, a treatise that offers valuable insights into the political structure and governance of the Maratha Empire under Shivaji Maharaj. His intellectual contributions remain a significant part of the historical record of the Maratha period.

Besides its historical significance, Pant Amatya Bavdekar Wada also holds cultural importance. The wada has been featured in several Marathi films, including Streedhan, Paus, Sattadhish, Madhu Ithe Chandra Tithe, Mumbaicha Phaujdar, Pachadlela, Binkamacha Navra, and Shhhh.. Koi Hai. These films highlight the wada's cultural relevance and contribute to its continued importance in the collective memory of the region.

Panyacha Khajina

Water systems form the foundation of every city, shaping daily life in ways often unseen. The essential infrastructure reaches every household, yet few understand the journey it has taken or how it has evolved. In Kolhapur, the legacy of water management is preserved in a historic reservoir known as Panyacha Khajina, meaning “Water Treasure.” This important structure stands as a lasting reminder of the early efforts by the city’s Public Works Department, which once played a pivotal role in establishing sustainable water solutions for the growing city.

The creation of Panyacha Khajina began in 1873 with the construction of a dam at Kalamba, situated at the base of Katyayani Hill. Water from this dam was directed to the Nangwili Dargah through a stone slab, utilizing the natural slope of the land. The project, planned and overseen by Major Walter Ducat, culminated in the completion of a large water storage tank in 1877. This tank is believed to have had a capacity of 294,500 gallons, which played an important role in supplying water to the city during that period.

The reservoir's creation was a joint effort, backed by philanthropist Baburao Keshav Thakur, a devotee of Ambabai from Pune, who saw the growing need for a reliable water source in Kolhapur and generously contributed 300,000 rupees to the project. His contribution is commemorated on a plaque at the tank, ensuring his role in this vital initiative is forever recognized.

The design of the reservoir was notable for its innovative use of the natural slope of the land, which allowed water to flow to various parts of the city without the need for electric pumps. This system was a remarkable achievement in water management for its time, providing an efficient and sustainable solution to the city’s needs. However, in recent years, the reservoir has faced challenges. The once-efficient system has suffered from mismanagement, leading to, as locals report, significant water wastage.

Panyacha Khajina remains a lasting symbol of Kolhapur’s early commitment to sustainable water management, highlighting the need for careful preservation and management of such critical infrastructure. It stands as a testament to the foresight, dedication, and collaboration that helped shape the city’s water systems, a legacy that the local community continues to take pride in even today.

Pavankhind

Pavankhind, situated approximately 17 km from Malkapur-Shahuwadi, stands as a significant historical landmark, commemorating one of the most valorous episodes in Maratha history. The site marks a decisive battle between the Marathas and the Adil Shahi dynasty. Accessible through winding roads from both Malkapur and Panhala, the name "Pavankhind" derives from the Marathi words Pavan, meaning sacred, and Khind, meaning mountain pass. The site was originally known as Ghod-Khind, which translates to "Horse Pass."

As described by historian Govind Sakharam Sardesai in New History of the Marathas (1957), the events leading to the battle at Pavankhind are set against the backdrop of the tumultuous years between 1658 and 1660. During this period, Shivaji Maharaj, with the help of his generals like Netaji Palkar, successfully captured significant portions of the Kolhapur region from the Adilshah of Bijapur. In addition, he had raided towns such as Raibag, Gadag, and Laksmeshvar. Infuriated by these actions and the death of his commander, Afzal Khan, at Shivaji's hands, the Adil Shah called upon his Viceroy, Siddhi Jauhar (Salabat Khan), to subdue Shivaji.

Salabat Khan, with the help of his allies, including Baji Ghorpade, Fazl Khan (Afzal Khan’s son), the Savant of Wai (Feudal lord of Wai), and Rustam Zaman, laid siege to the fort of Panhala in mid-1660, where Shivaji had taken refuge. With their overwhelming numbers, the Bijapur forces also brought heavy artillery, including guns and ammunition procured from the English in Rajapur. These weapons were causing significant damage to the fort’s walls and were demoralizing Shivaji’s forces. To make matters worse, news arrived that Shaista Khan, a renowned Mughal commander, had taken control of Pune and Baramati, threatening further advances into Shivaji's territory.

Recognizing the dire situation, Shivaji negotiated a temporary truce with Salabat Khan. As the siege operations paused, Shivaji seized the opportunity to escape on the night of July 13, 1660. He slipped out of the fort with a small party of loyal followers, including Baji Prabhu Despande, and set off for Vishalgad, braving the heavy July monsoon rains.

Once Shivaji’s escape was discovered, Salabat Khan quickly ordered a pursuit. His forces were close to capturing the Maratha king when Baji Prabhu Despande, with a few soldiers, made the selfless decision to hold the Ghod-Khind pass and delay the advancing Bijapur troops. This heroic stand, which lasted several hours, resulted in Baji Prabhu being mortally wounded, and his small band of men was wiped out. However, it is believed that Baji Prabhu, in his final moments, was told, rightly so, that Shivaji had reached Vishalgad safely.

This act of valor has been immortalized in Maratha history, and the pass was subsequently renamed Pavankhind, reflecting its newfound sanctity due to Baji Prabhu's sacrifice. The path taken by Shivaji from Panhala to Pavankhind on that fateful night is now known as Shaurya Waat ("Path of Bravery").

Today, Pavankhind has become a popular destination for trekkers, Maratha history enthusiasts, and visitors alike. A Samadhi (Shaurya Sthal) has been erected to honor the sacrifice of Baji Prabhu Despande and his brave men, ensuring that their heroism is never forgotten.

Ramling Mandir

Among the many ancient mandirs that dot the landscape of Kolhapur, the Ramling Mandir stands out, not only for its age but for its deep connection to the time of the Ramayan. Possibly the oldest mandir in the region, the Ramling Mandir is situated in the quiet village of Alte, within the Hatkanangale taluka of Kolhapur district. Surrounded by lush forests and abundant biodiversity, this cave mandir is dedicated to Lord Shiva, worshipped in the form of a shivling. Local lore holds that during his 14 years of exile, Lord Rama visited this very spot and established the shivling, thus giving the mandir its name, Ramling.

![Ramling Mandiris located near Palsambe in the Gaganbawda Tehsil of Kolhapur District.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/cultural-sites/ramling-mandiris-located-near-palsamb_Abol6tn.png)

What makes the mandir even more remarkable, as locals recount, is the constant flow of water that drips onto the shivling, a phenomenon that occurs year-round, regardless of the season. Whether it’s the summer heat, the monsoon rains, or the winter chill, water continues to drip without interruption. Local stories tell of Bhagwan Ram, who, using his arrows, carved channels in the caves to ensure the continuous flow of water. This natural wonder has captivated devotees for centuries, drawing hundreds of visitors each year, eager to witness the miracle and seek blessings.

Shalini Palace

Shalini Palace, located on the western side of Rankala Lake in Kolhapur, is a striking example of architectural grandeur. Built with black stone and Italian marble, the palace stands out for its elegance and timeless appeal. The palace’s history is as unique as its design, having served multiple roles over the years. While its identity has evolved, locals say the building’s design reflects the royal heritage of Kolhapur, making it a symbol of the region’s rich history.

Built between 1931 and 1934, the palace was commissioned by Chhatrapati Shahaji II and Queen Pramila Raje for their daughter, Princess Shalini Raje. According to local historians, the project cost around 8 lakh rupees and took four years to complete.

The building’s history includes several transitions. In the 1960s, it briefly served as a college, but was later closed due to high maintenance costs. In 1987, the palace was converted into what locals remember as Maharashtra's first and only palace hotel, gaining recognition for its exceptional service. However, the hotel ceased operations in 2014. Today, visitors can only admire the exterior of the palace and its surrounding gardens.

At present, the palace is in debt and may be sold at auction, and is currently off-limits to tourists. However, despite its various changes over the years, Shalini Palace continues to be an important and historic site in Kolhapur.

Shankar (Mahadev) Mandir, Kasba Beed

The Shankar (Mahadev) Mandir, located in the Kasba Beed region, is deeply rooted in local legends connected to the Mahabharata. It is believed to have been constructed by the Pandavas in a single night. The mandir is known for its unique feature: the sun’s rays are said to enter the mandir from the west, which is considered highly unusual for a mandir of its kind.

The area surrounding the mandir is also the subject of folklore, with claims that gold can still be found around the premises. One of the mandir's key rituals involves a palki procession, in which the idol from the mandir is carried across the Bhogawati River to Pandharpur, a practice that continues to attract attention from devotees.

On Mondays, it is a rare custom for women to visit the mandir, as it is typically seen as a day to break fasts. The Shankar Mandir remains a significant religious and cultural site, blending historical mystery with enduring traditions.

Shri Binkhambi Ganesh Mandir

Shri Binkhambi Ganesh Mandir is located in the Shivaji Peth area of Kolhapur, close to the famous Mahalakshmi Mandir. The mandir is believed to have been discovered in 1882 while repairing a well in the area. The name "Binkhambi" refers to the unique design of the mandir’s sanctum sanctorum, which was built without any supporting pillars. "Binkhambi" literally means "built without pillars."

Some locals claim that the Ganesha idol in the mandir predates the structure itself. The idol, made of stone and colored orange, is a focal point of devotion for many. The mandir's exterior is adorned with carvings of tortoises, adding to its distinctive architectural style.

Siddhagiri Math (Museum)

While many museums showcase collections of ancient artifacts and grand historical remains, the Siddhagiri Gramjivan Museum, nestled in the village of Kaneri, offers something truly unique. Unlike traditional museums, this miniature museum seeks to recreate the ancient practices and way of rural living, bringing them to life in vivid detail.

Spanning seven acres, the Siddhagiri Gramjivan Museum, also known as Kaneri Math, is a miniature museum dedicated to depicting the practices, crafts, and way of life from ancient rural India. Established by the Siddhagiri Gurukul Foundation, the museum showcases over 300 sculptures and 80 scenes that capture the essence of rural life. Visitors can explore scenes of traditional homes, a goldsmith at work, and farmers tending to their cattle, an immersive journey into the daily life and customs of ancient Maharashtra. This focus on rural life explains why it’s also called the “Gram Jivan Museum” (Village Life Museum).

Alongside rural depictions, the museum also showcases sculptures of important figures from India’s past, such as Sushruta, the pioneering surgeon of ancient India. These exhibits provide a valuable educational resource, especially for younger visitors, shedding light on the contributions of ancient Indian scholars in fields ranging from medicine to science.

While the museum showcases an impressive array of exhibits, its significance extends far beyond the displays. The village of Kaneri, which houses the museum, has long been a site of spiritual and historical importance. According to the Siddhagiri Math website, Kaneri has been a tirth yatra since the 7th century. It is believed that Shri Niramay Kadsiddheshwar, the first Kadsiddheshwar Swamiji, settled here, laying the foundations for the region’s religious significance.

The mandir located within the museum premises, believed to be around 500 years old, stands as a testament to the rich legacy of Kaneri. Local legend suggests that Shri Niramay Kadsiddheshwar, the first Kadsiddheshwar Swamiji, placed a shivling here. Until the 14th century, the mandir stood without a protective wall, after which it was enclosed with a cladding to preserve and safeguard it.

Over the years, the Math has grown significantly. In 1989, Shri Samarth Muppin Kadsiddheshwar Swamiji Maharaj, the 48th Mathadipati, introduced a set of Sutras that continue to guide the Math's spiritual practices today. Under his leadership, the Math flourished, reinforcing its cultural and spiritual traditions. At the entrance of the Shiva Mandir, visitors are greeted by a towering 42-foot Shiva murti alongside a large Nandi statue.

Temblai Devi Mandir

Perched atop the Temblai Hill in Kolhapur stands the Temblai Devi Mandir, a revered religious site. Dedicated to Temblai Devi, a manifestation of Durga Devi, it is especially significant for women who visit in large numbers to seek blessings for a virtuous partner or the well-being of their loved ones. The hill is also known for its healing properties, with the fresh winds once believed to have curative effects, particularly for tuberculosis patients.