Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Fossil Remains from the Paleolithic Age at Harwadi

- Acheulian Tools Near the Harwadi Site

- Early Empires and Political Shifts

- Early Chalukyas and their Grants

- Latur as a Major Centre for theRashtrakutas of Lattalur

- Lattalur under the Chalukyas of Kalyani

- Yadavas and Latur’s Connection to General Kholeshwar

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate

- Bahmanis

- Barid Shahi of Bidar

- Nizam Shahi of Ahmadnagar

- Mughals

- Marathas

- Nizams of Hyderabad

- Battle of Udgir (1760)

- Treaty of Udgir

- Battle of Palkhed and Maratha Revenue Rights

- Maratha–Nizam Engagements in Tandulja and Udgir

- Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountcy

- Rohilla Raids and Suppression

- Bhalki Conspiracy of 1867

- Arya Samaj

- Trade Importance

- Maharashtra Parishad

- Post-Independence

- Lift Irrigation Scheme in Latur, 1954

- Latur as a Pilot Area for Joint Farming Societies, 1966

- Killari Earthquake, 1993

- Sources

LATUR

History

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Latur district, located in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra, has a significant historical legacy which dates back to pre-historic times. In recent decades, remarkable discoveries near the Manjra River have revealed that this landscape was once home to a wide range of animals — including elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, horses, buffaloes, deer, and even tigers. These fossilised remains, found near the village of Harwadi in Renapur taluka, date back nearly 50,000 years. Just a short distance away, archaeologists also uncovered stone tools made by early humans, placing Latur among the few regions in Maharashtra with direct evidence of both prehistoric wildlife and human presence in the same area.

Went on to become a major center for the Rashtrakutas. Historically, Latur formed part of Dharashiv district and shared its administrative course through several regimes. Under the Nizam’s Hyderabad State, both regions were governed as a single unit, a structure retained through Bombay State and, later, Maharashtra. It was only in 1982, that Latur was established as a separate district.

Etymology

The name Latur is believed to have originated during the period of Rashtrakuta rule, which likely extended over the region between the 7th and 8th centuries CE. According to the Osmanabad district Gazetteer (1972), the area was then known by the names Lattalurpurvaradhishwar and Lattalur. The latter is thought to be associated with the Rashtrakuta king Amoghvarsha, under whose reign the settlement is believed to have held some prominence.

There is, moreover, an intriguing theory that the very name Latur springs from the word Rashtrakuta itself. This conjecture owes much to the work of the historian Ganesh Hari Khare, who contended that the region was, in truth, the place of origin of the dynasty. Based on Rashtrakuta-era records, Khare identified several place-names with modern locations in and around Latur district:

- Talayakhed as Talikhed, on the Terna river near Nilanga

- Rattagiri or Ratnagiri as Latur

- Chinchwali as Chincholi in Latur taluka

- Anjirika river as the Wanjra or Manjara river

- Uchhal as Usturi

Based on these correlations, Khare concluded that the Latur region was closely associated with the early history of the Rashtrakutas, possibly as their homeland.

The district also appears as Lattalura in records from the reign of Someshvara III of the Western Chalukyas, who ruled in the early 12th century. Over time, the name evolved into its present form, Latur.

Ancient Period

Fossil Remains from the Paleolithic Age at Harwadi

Latur has a long history that, as noted earlier, stretches back to prehistoric times. One trace of this early past can be found in the upper Manjra Valley, near the village of Harwadi, where researchers have uncovered one of Maharashtra’s most extensive fossil sites. First identified in 2003, this site contains the remains of animals that lived here around 50,000 years ago, during the Late Pleistocene period.

The fossils were found in a layer of sandy gravel resting on the Deccan basalt. They include the bones of elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, horses, cattle, buffaloes, blackbuck, sambar, swamp deer, and spotted deer. Shells of freshwater molluscs and remains of tortoises were also recovered. Notably, fossils of tigers were found here, which is regarded to be a rare occurrence in the Indian peninsular. Similar discoveries have only been made in a few other places, such as the Hunsgi-Baichbal valley and the Kurnool caves.

The bone layer appears largely undisturbed, with many complete or nearly complete skulls and limbs found intact. The location of the fossils suggests that these animals may have lived around slow-moving water sources, possibly swamps or river pools along the Manjra.

Acheulian Tools Near the Harwadi Site

In 2009, Acheulian stone tools were discovered in close proximity to the fossil beds, roughly 100 metres from the main faunal deposit. The artefacts include hand axes and cleavers, characteristic of Lower Palaeolithic tool industries.

Their presence is believed to indicate that early humans inhabited the region during the same period as the animals represented in the fossil record. Scholars remark that this marks one of the few documented instances in Maharashtra where Acheulian tools and a Pleistocene faunal assemblage occur in the same stratigraphic context.

Early Empires and Political Shifts

Over the course of history, the region now forming Latur district has fallen under the influence of many different political and cultural powers. Little is currently known about its early history, however, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These are better understood when placed in the context of present-day Marathwada and the Deccan regions, to which Latur has long been linked by geography, political influences, and culture.

In the 3rd century BCE, among the several dynasties that ruled the Deccan, the Mauryas are known to have exercised authority in parts of present-day Maharashtra. Ashokan edicts found in Palghar and Chandrapur point to their reach, while one in Sambhaji Nagar, within modern Marathwada, has been interpreted by many scholars as referring to two political entities, local chieftains, some of whom perhaps under Mauryan influence.

With the decline of Mauryan power, the Satavahanas rose to prominence in the Deccan region. During the period of their reign, the tract now forming Latur district appears to have served as a point of passage along important inland trade routes. Notably, the neighbouring town of Ter, in the present Dharashiv district, had by this time become a centre of commerce. Coin-moulds of the period found there indicate a scale of currency production uncommon for the age, and probably driven by active trade. According to scholars such as Harihar Thosar and V. Sarde, this commercial activity was served by several routes passing through Latur. One highway from Veer in Maharashtra to Satrati in Madhya Pradesh crossed the district, and another, linking Ter to Rome by way of Sannati in Karnataka and Balipattan in Goa, also traversed it.

The period following the Satavahanas saw the rise of the Abhira dynasty in parts of western Maharashtra. The Osmanabad district Gazetteer (1972) notes that the most significant source confirming Abhira rule is an inscription of Rajan Isvarasena, found in a cave at Nashik, which marks the beginning of the Kalachuri-Chedi era around 250 CE.

While no inscriptions or coins of the Abhiras have been discovered yet in Latur district, their presence in neighbouring regions—including Nashik, Sambhaji Nagar, and parts of the Khandesh region and Gujarat—suggests that some level of Abhira influence or control may have extended into the district during this time. The nature of this presence, whether administrative or military, remains uncertain. Following the decline of the Abhiras, political authority in the Deccan appears to have shifted toward the Vakataka dynasty, which rose to prominence in the early 4th century CE.

At this time the land that now forms Latur lay within the region of Kuntala, stretching across southern Maharashtra and northern Karnataka. This tract, including Pune, Satara, Sangli, Kolhapur, Solapur, and parts of Belgaum, was ruled by the Rashtrakutas of Manpur, who, according to the Osmanabad district Gazetteer (1972), may have invaded Latur and built a fort here.

Early Chalukyas and their Grants

In the period following Rashtrakuta control of the Kuntala region, political authority in the Deccan shifted to the Chalukyas of Badami. During this time, the Latur region was under Chalukya rule, and appears in early land grant records connected to educational and religious institutions.

One such record, preserved in a copperplate inscription from Kurnool (Andhra Pradesh), refers to a grant of land in Latur to Brahmins engaged in the study and teaching of the Vedas. The donation was made at the request of Devshakti Raj, a local ruler of the Sendraka lineage. He is believed to have been responsible for administration at Nalwadi (identified with modern-day Naldurg in neighbouring Dharashiv district.) The same inscription mentions a place named Ucchiv, which scholars consider to be present-day Ausa of Latur district.

Notably, remains of this period are still to be seen in Latur district. Among the better-known are the Kharosa caves and the Udgir Fort, which are attributed to this time.

Latur as a Major Centre for theRashtrakutas of Lattalur

With the decline of Chalukya authority in the Deccan, control of the Latur tract passed to the Rashtrakutas of Lattalur. From this point the district enters the record not only as part of a wider territory of the dynasty but also as a place of much significance to them. As mentioned above, the earlier name of the present-day district, Lattalur appears in several sources as the ancestral seat of the Rashtrakutas, and in some accounts as their place of origin.

Interestingly, it was from Lattalur, according to tradition, that Dantidurga rose to found Rashtrakuta power in the Deccan. His successors maintained the connection. Under Govind III, the capital was transferred from Ellora to Mayurkhandi in present-day Bidar district. This move, placing the seat of government in proximity to Latur, brought the district into closer contact with the affairs of state.

Traces of this integration is found in the copperplate grants of Govind’s reign. Four are known—two discovered at Umarga and Tuljapur in Dharashiv district, and two at Ausa and Ahmadpur in Latur itself—each recording gifts of land. Such records point to sustained administrative activity in the area.

Amoghavarsha I, Govind’s son, further strengthened the association between the dynasty and Lattalur. In inscriptions at Shirur and Nilgund he styled himself Lattalurpurvaradhishwara and Lattalurpurparameshwara. Although the capital was later removed to Malkhed (Manyakheta) in 850 CE, he is believed to have spent much of his reign in Lattalur, possibly in consequence of political unrest in his early years. Remains of this period are believed by some to lie buried along the banks of the Manjara river that flows in the district.

Notably, the Rashtrakuta rulers were distinguished for their religious patronage and a degree of syncretism in faith, and their influence in this regard is evident within the district. Under Amoghavarsha and his successor Krishna II, Jainism enjoyed particular support, and it is said that a peeth was established at Ausa which lies in the present-day Latur district.

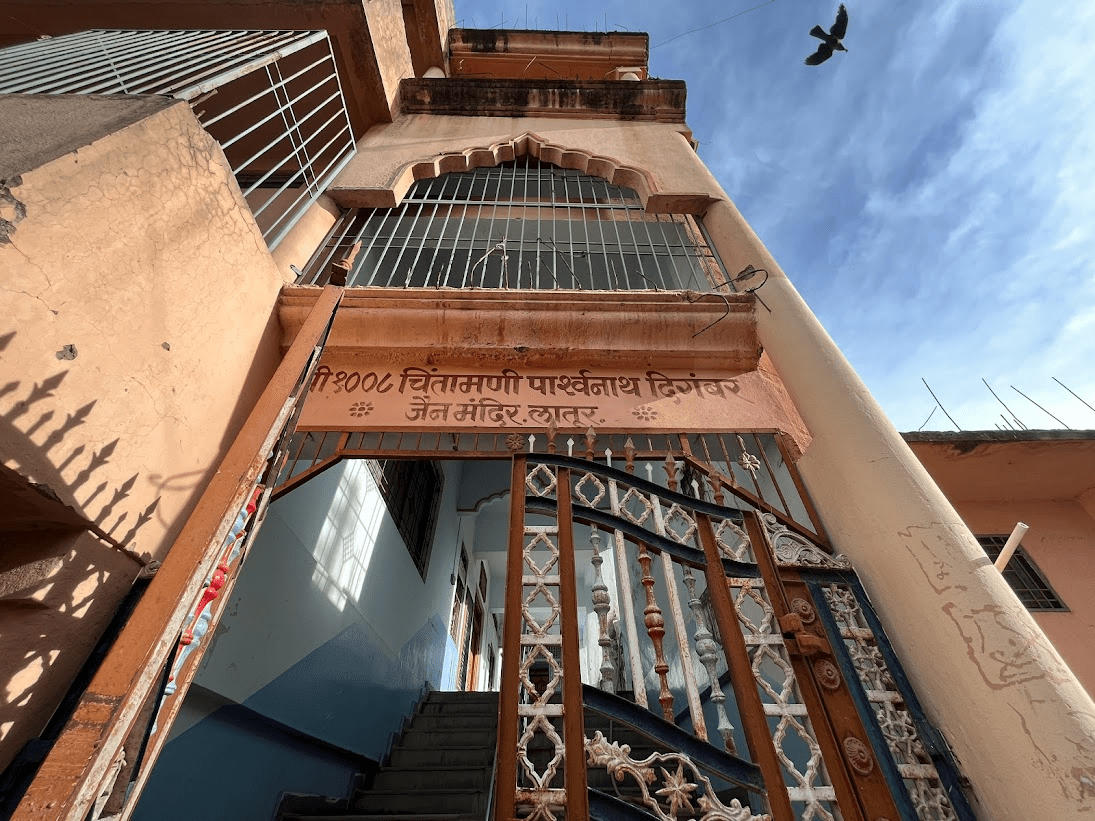

Structures of the period also survive in the district. Of these, the Shri 1008 Chintamani Parshvanath Digambar Jain Mandir in Old Latur is the most notable. Although rebuilt on several occasions—the last in 2003—it is believed to occupy a site first consecrated in the Rashtrakuta age. At its centre stands a black stone image, three feet in height, of Chintamani Parshvanath, the 23rd Jain tirthankara. The temple, recognised as an Atishaya Kshetra, remains as one of the most well-known places of worship in the district.

Lattalur under the Chalukyas of Kalyani

Following the decline of Rashtrakuta authority, the region passed under the control of the Chalukyas of Kalyani, who are also known as the Western Chalukyas. Notably, at no point during this transition did the importance of the Latur region—then known as Lattalur—appear to diminish. On the contrary, the available epigraphic, architectural, and institutional evidence from this period suggest that Latur retained its administrative relevance and developed further as a centre of education and religious activity.

At first, the Chalukya kings governed from Malkhed (Manyakheta), the former Rashtrakuta capital. It was only in the reign of Someshwar I, during the mid-11th century, that the capital was transferred to Kalyanpur — the present-day Basavakalyan in Bidar district. Lattalur, situated between these two political centres, remained closely tied to the capital region both geographically and administratively. Throughout the period, it continued to function as a regional node of significance.

Inscriptions from the 11th and 12th centuries particularly attest to this. These records speak to land grants, temple endowments, water management schemes, and the routine workings of local governance. In function, if not in formal designation, Lattalur operated as a provincial node of considerable weight.

A notable inscription, located at the Papvinash Mandir in Latur, and dating to the reign of Someshwar III, refers to the presence of over five hundred scholars residing in the town. The same document describes Lattalur as a pattana—a term typically reserved for significant urban centres—indicating both demographic density and institutional sophistication. That such a number of learned men should reside in one place suggests the presence of established schools and religious institutions, possibly with royal or local patronage.

Further inscriptions have been recorded from nearby settlements — Shirur, Ganeshwadi, Ausa, and Nilanga — each contributing details to the picture of a region under active administration. Of particular note is a 12th-century inscription from Kasar Balkunda, in Nilanga taluka, dated to 1140 CE, during the reign of Jagadekamalla II. Written in Old Kannada, it records a land grant made by Mallara Bilayya, following the consecration of a temple to Somanatha, Nandikeshwara, Keshava, and the Sapta Matrikas at Bedtikere Ballakunde. The king is referred to by the titles Prithvivallabha and Maharajadhiraja, and the inscription includes the phrase Godavari Nadeveedi, interpreted by scholars as referring to the Chalukya dominion over parts of the Godavari basin. The inscription survives at the site, now known as Teerth Mahadev Mandir.

It is important to note that much of the religious and architectural activity during this period was undertaken by local officials rather than the royal court. In Ahmadpur taluka, mandirs at Himpalgaon and Ganeshwadi were built by Bhim and his son Kalidas, who both served under Vikramaditya VI. A similar pattern is seen in Shirur Anantpal, where two mandirs — Ananteshwar and Somnath — were established. The Ananteshwar Mandir, particularly, is attributed to Anantpal, a local dandanayaka, who also founded an attached school. The Somnath Mandir was later repaired by Elayaditya Bane, after which it came to be known as Elevamath. Though altered over time, both mandirs retain features characteristic of the later Chalukya style.

These Mandirs were, in several cases, also closely associated with institutions of learning. At Ganeshwadi, a Saraswati Mandap served as a centre of instruction. Shirur Anantpal also supported a pathshala, while a Jain basti at Samling Mudgal functioned as a residential school. Together, these institutions suggest a local culture that valued formal education, sustained by religious foundations and supported by the surrounding settlements.

In parallel with temple construction and educational endowment, attention was given to the provisioning of water. A number of tanks and reservoirs from this period have survived in various states of preservation. Among these, the Bhimasamudra—though now largely silted—retains portions of its original stone embankments. Another tank, situated at Kalambad (ancient Kalubarak), is attributed to Bhimnath Senapati, while others are found at Kandhar, Jhari Buzurg, and near the Siddheshwar Mandir in Latur.

Yadavas and Latur’s Connection to General Kholeshwar

Following the decline of the Western Chalukyas in the late 12th century, control of the Deccan gradually passed to the Yadavas of Devagiri, also known as the Seuna dynasty. Under Bhillama V, who established the dynasty’s stronghold at Devagiri, the Yadavas expanded their territory into former Chalukya domains. This included the annexation of Kalyanpur (modern Basavakalyan), the former Chalukya capital. During this phase of expansion, Lattalur — previously a Chalukya administrative centre — was incorporated into the Yadava kingdom.

Notably, Latur’s proximity to the eastern boundary of the Yadava domain placed it near the frontier with the Kakatiyas of Warangal, and the area was involved in repeated conflicts between the two kingdoms. The region remained politically active under Yadava rule, with local administration entrusted to appointed generals and officials. Among these was the famous Kholeshwar, who is recorded as overseeing the territories of Ausa and Udgir, then referred to as Ausdesh and Udgiridesh (interestingly, Mandirs and inscriptions associated with Kholeshwar have been identified at Ambajogai, Beed, and Akola, pointing to a figure of more than local influence).

Other than this, other inscriptions also offer additional insight into the political structure of the time. A copperplate dated 1019 CE refers to a local figure named Kanhardev, a subordinate ruler under the Chalukya king Jai Singh II, whose authority appears to have been acknowledged, at least nominally, by the early Yadavas. Kanhardev is described as a descendant of Maharatta Mamma and is referred to in the inscription as Lattalurpurvinirgat, or “native of Lattalur.” He is said to have ruled from Bhogvardhan (likely the present-day Bhokardan, Jalna district), and his marriages to Jakvabai and Lakshmibai, daughters of Tailap II—founder of the Kalyani Chalukya dynasty—suggest an established position within the elite political networks of the time.

While it remains unclear whether his authority extended into the Yadava period in any formal capacity, the record nonetheless points to the continued relevance of Lattalur’s local elites across successive dynastic transitions.

Medieval Period

Delhi Sultanate

In 1294 , Alaudin Khijli invaded Devagiri after defeating Yadav king Ramchandradev. The latter was forced to give away a huge part of his wealth to Alauddin in exchange for some jagirs. Revenue collected from these jagirs would have to be sent to Khilji’s kingdom in Delhi annually. Moreover, Khilji also married Ramchandradev’s daughter Jyeshthapalli.

This incident is recorded in the writings of historians Amir Khusro, Ziauddin Barani, and Isami Futuh. Other territories towards the South including Devagiri were also conquered. Naturally, present-day Latur district, which was part of the Deccan, also became a part of the Delhi Sultanate.

After the death of Ramchandradev in 1312, his son Shankardev Yadav succeeded him. Shankardev Yadav had taken a great dislike to Alaudin and refused to send annual revenue to him. For three years, the Yadav king ignored Khilji’s orders after which Alauddin ordered Malik Kafur to kill the Yadav king. In the battle that followed, he defeated Shankardev Yadav and killed him. Malik Kafur remained in Devagiri for some time and helped expand Muslim power in the South.

When Alaudin Khilji’s health was failing, he asked Malik Kafur to come to Delhi to nurse him. When Kafur came back, the Muslim grip on Devagiri loosened. Ultimately, many Southern kingdoms became independent after Khilji’s death. Then, Harpaldev, who was married to one of Ramdevrao’s daughters seized the throne of Devagiri. However, his reign was short-lived and the kingdom came under the control of the Tughlaqs.

The rule of the Khiljis was followed briefly by the Tughlaqs though it was rife with frequent rebellion from their generals. Most notably, in 1327 CE, Mohammed bin Tughlaq, the second ruler of the Tughlaq dynasty shifted his kingdom’s capital from Delhi to Devagiri and renamed it as Daulatabad. However, in 1335, due to administrative inconvenience and fear of losing control of the Northern part of his empire, he shifted the capital to Delhi again. After Mohammed bin Tughlaq’s death in 1351, one of Tughlaq’s rebellious generals known as Alauddin Bahman Shah went on to establish a separate dynasty known as the Bahmani Sultanate.

Bahmanis

Later, in the mid-14th century, Alauddin Bahman, who founded the Bahmani kingdom announced that Gulbarga (Karnataka) would be his administrative capital. Gulbarga’s close proximity to Latur led to the latter gaining centre stage in many political movements. For some time, Latur and its neighboring areas witnessed stable administration. But, after Alauddin Bahmani’s death in 1358, many kings ruled the area albeit in short spells of time.

From 1396 to 1409 CE, during the reign of Mohammed Shah Bahmani, Latur and its neighboring areas were devastated by the Durgadevi famine. This disaster was caused due to long periods of no or little rain. More than half of Latur’s population perished. Several years after the famine had ended, in 1421 and 1422, Latur experienced little rainfall. During these years, cattle and farm animals are reported to have died in large numbers.

Shahabuddin Ahmed ascended the throne in September 1422 CE. In 1424, the kingdom’s capital shifted from Gulbarga to Bidar. Shahabuddin Ahmed renamed Bidar as Muhammadabad and appointed Khalaf Hasan Basri as Malik-ut-tujjiir. For the next couple of years, Basri assumed full control of the region. He ensured that people who had been displaced due to the famine were provided resettlement. Along with giving away a plot of land for free, a horse bag of grain was also provided to these villagers.

In 1460 CE, another famine ravaged the Deccan area. This famine is referred to as the Damaji Pant famine. It is named in honour of Damaji Pant, the revenue officer at that time who distributed grains to those in need.

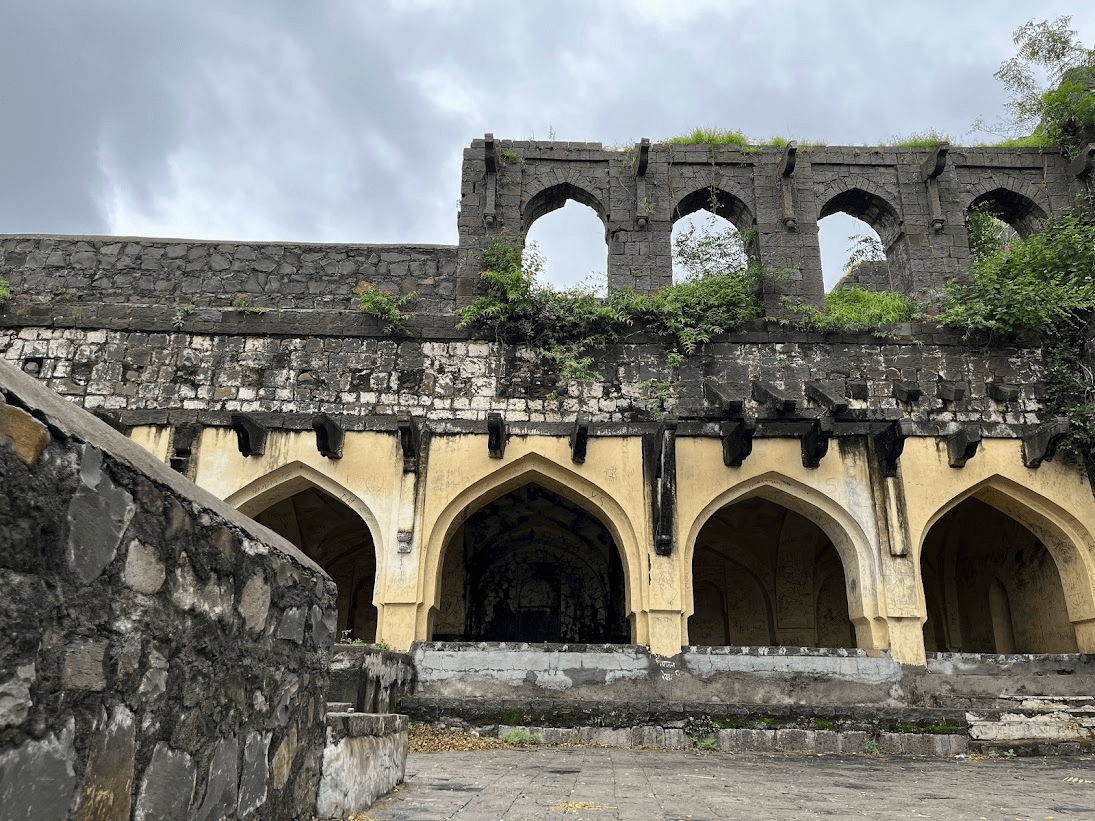

In 1466 CE, Nizam Shah Bahman ascended the throne. During this time, Mahmud Gawan became his guardian and wazir. He was the most influential wazir of the Bahmani period. The forts of Udgir and Ausa in Latur district were built by Mahmud Gawan when he was the chief wazir of the Bahmanis.

After the death of Mahmud Gawan, the Bahmani dynasty began to decline. After Mahmud Shah’s death, Shahabuddin Mahmud came to the throne in 1482 CE. As he was a minor, attempts were made by senior chiefs to keep the sultan under their thumb. One of these chiefs was Qasim Barid who later became the founder of the Barid Shahi sultanate.

The last sultan, Kalimullah, had sought the help of Emperor Babur and offered to grant the provinces of Vanhad and Daulatabad. But the plot was exposed. He gathered that his life was in danger, and he fled to Bijapur and later to Ahmednagar in 1526 CE. However, he was captured and put to death. His son, Ilham Allah escaped to Mecca and thus, the Bahmani dynasty came to an end.

Barid Shahi of Bidar

Qasim Barid, the founder of the Bidar sultanate was a native Turk. Khwaja Shahabuddin Ali Yezdi brought Qasim Barid to Bidar as a slave after which he began serving Sultan Mahmud Shah. Barid was an able leader and was soon promoted to the position of a chief. During the reign of Mahmud Shah, the Maratha rebels of Paithan and Chakan invaded Pundai. Qasim Barid was sent to handle the rebellion. In 1492, Mahmud Shah gave him the fort of Udgir as jagir for his success. During the reign of Sultan Mahmud Shah Bahmani, he captured the forts of Ausa, Kachar, and Udgir and allowed Bahmani Sultan control of the cities and fort of Bidar. His other chiefs revolted and he was defeated at Deoni. Yet, Qasim Barid planned to remove Mahmud Shah Bahmani from the throne. He did not succeed in this and stayed in the fort of Ausa. Qasim Barid died in 1504 CE. He was succeeded by his son Amir Barid. The sultans after Qasim Barid had frequent conflicts with the Qutub Shahi, Nizam Shahi, Adil Shahi, and kings of Vijayanagar.

In 1528 CE, Ismail Adilshah attacked Bidar. At that time, Amir Barid was at Udgir. In this battle, Sardar Asad Khan of Bijapur captured Amir Barid and took him to Bijapur. He realized this was a conspiracy devised to kill him. Therefore, he offered Udgir fort and a huge portion of his Bahmani treasury to Adil Shah. Meanwhile, his son Ali Barid gathered troops outside Bidar fort. Thus, he handed over the forts of Kandhar and Kalyani to Adilshah. Later, Amir Barid became the Mandlik of Bijapur. After his death, Ali Barid ascended the throne.

In 1492 CE, as the Bahmani empire declined, Mahmood Shah Bahmani ceded Udgir (along with Ausa and Kandhar forts), to his prime minister Qasim Barid, establishing the Barid Shahi dynasty (1492–1619 CE). Udgir Fort then served as a key administrative and military center under Barid rule.

Nizam Shahi of Ahmadnagar

The Nizam Shahi of Ahmadnagar included the present Latur district. The first ruler of the Nizam Shahi was Malik Ahmad who was the son of one of the Bahmani state’s trustees. Muhammad Bahmani III appointed Malik Naib as the trustee of the state and the guardian of his son, Mahmud Shah. His wazir Mahmud Gawan began doubting the loyalties of Malik Naib and his ambitious son, Malik Ahmad. As soon as Malik Naib came to know about Gawan’s suspicion, he fled and took refuge in Bidar. He stayed with Pasand Khan, a city official. But, Pasand Khan betrayed his trust and he killed him. Upon knowing this, Malik Ahmad increased his army and his chief defeated the Sultan's army at Paranda.

Malik Ahmad was not a favourite amongst other court officials and hence, he began to function independently from 1486 CE onwards. After his death in 1508, his seven year old son Bunhan Nizamshah ascended the throne. During his reign, Pathri, Daulatabad, Mahur, and Paranda forts were controlled by Nizam Shahi. When his lawyer was insulted by Baridshah's brother at the latter’s court, Nizam Shah invaded Bidar to avenge him. First, he besieged the fort of Ausa. In retaliation, Ibrahim Adil Shah and Ali Barid Shah jointly attacked Burhan Nizam Shah at Ausa, in which the Nizam Shahi won.

In 1548 CE, Burhan Nizam Shah conquered the forts of Kandhar, Udgir, and Ausa. By this period, almost all the territories of the Bidar state were brought under the control of Nizam Shahi.

Bunhan Nizam Shah died on 30 December 1553. Thereafter, his son Miran Shah Hussain came to the throne in 1554 CE. In 1559, a treaty was made between Husain Nizam Shah and Ram Raja of Vijayanagar. In 1562, Nizam Shah was jointly attacked by Ram Raja, Adilshah, Ali Barid, and Imadshah. So he sent his wife to the fort of Ausa. During his time an iron gate was erected in the fort. This is recorded in the inscription on the fort. Husain Nizam Shah died on June 6, 1565.

Ibrahim Adilshah declared war on the Ahmadnagar Sultanate in 1584 CE and laid siege to the fort of Ausa. Khudita, the sister of Ibrahim Adilshah, was married to Miran Hussain Nizamshah.

Mughals

With the end of Nizam Shahi in 1633, the district gradually became a part of the Mughal Empire. It was Shah Jahan who decided to launch his campaign against the remnants of the Nizam Shahi Sultanate. He met Adilshah on 19 January 1636. When negotiations failed, he ordered the demolition of Udgir and Ausa forts. An Abhaypatravaj decree was given to Adilshah on 14 May 1636. This decree was received by Adilshah on 20 May 1636. After signing and sealing, he acceded the diamond, rubies, assassins, and elephants, among other offerings, on 1 June 1636.

After Adilshah’s surrender, Shah Jahan left Daulatabad and appointed Prince Aurangzeb as subedar of the South. Aurangzeb found that Adil Shahi still controlled the forts of Udgir and Ausa. After the treaty with the Bijapurkars, Shah Jahan’s men tried to take control of these forts peacefully but did not succeed. So they attacked Udgir. On 17th August 1636, the fort was besieged. One of Shah Jahan’s chiefs planted mines under the ramparts of the fort and lit one of them. This caused cracks in the fort’s walls. Yet, this could not be considered as an intrusion. He did not blow up other mines so as not to endanger the grandson of Ibrahim Adilshah II who was present in the fort. Then, he summoned a representative from the fort and showed him the military readiness and fortifications. Upon seeing this, the fort keeper surrendered on 28 September 1636. This incident has been inscribed in Persian on the left side of the black stone arch at Udgir fort.

In 1658 CE, Aurangzeb left the Deccan to claim the throne of Delhi. Meanwhile, the Mughal sabha of the South was ruled by nine Sarasubedars. Latur region was also included in this sabha. From 1682 to Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Sarasubedars lost their importance as he was in the Deccan. There was a constant war between Aurangzeb and the Marathas for the last 25 years of his life. After his death, the subedari kept changing as and when emperors in Delhi succeeded to the throne.

Marathas

The district was under Maratha influence, especially during the 18th century, as it was part of Dharashiv district. Dharashiv was significantly impacted by Maratha expansion, particularly during the time of Peshwa Bajirao I, who asserted Maratha claims over the Deccan through campaigns and treaties. This influence extended across the broader region, including Latur. The Battle of Udgir in 1760 (more below), fought within present-day Latur district, is a direct testament to Maratha presence and military activity in the area. Moreover, the Marathas collected chauth and sardeshmukhi—taxes that applied across Deccan territories, including both Osmanabad and Latur. Given their shared governance, strategic location, and evidence of Maratha military operations, it is reasonable to assume that Latur, like Dharashiv, was firmly within the Maratha sphere of influence during this period.

It is also said that the Maratha started making inroads in the district from 1660 CE onwards. In 1670 CE, Shivaji Maharaj's army besieged the fort of Ausa. According to the Gazetteer (1972), the fort keeper at Udgir conveys that Shivaji Maharaj's army had tried to capture the fort of Udgir. There are many other instances where the Maratha army attacked the forts occupied by Mughals and looted them.

Nizams of Hyderabad

In 1724, an independent state was established in the south. This was the Nizam Shahi of Hyderabad. The Nizam's dynasty was known as the Asaf Jahi dynasty. The present Latur district was also a part of this state. Unlike British-controlled provinces (e.g., Bombay, Madras), Hyderabad was a princely state under the British Raj's indirect control.

After the death of the Nizam on 21 May 1748, his son Nasir Jung and his daughter's son Muzaffar Jung fought for the throne in which the latter emerged victorious. During this time, Hyderabad was ruled by the French. When he was killed, the French appointed Salabatjung (second son of the Nizam) became the ruler. He faced constant threat from the Peshwas. After a fierce four day battle, the Nizam conceded defeat on 17 December 1757. At the same time, the British defeated the French in a power struggle in the Deccan. Thereafter, Salabatjung bestowed all his administrative powers on Nizam Ali.

Nizam Ali came to Udgir and camped in November 1759. In the battle of Udgir, the Peshwas sent Marathi troops under the leadership of Sadashivrao Bhau and stayed in the city fort for supervision. The Marathas went to war with the Nizam's army from 11 January 1760 near Udgir. In the beginning there was a little clash. On 19th and 20th January 1760, a great battle took place at Tandulja in Latur taluka.

Battle of Udgir (1760)

The Battle of Udgir, fought in 1760, was a pivotal confrontation between the Marathas, led by the capable commander Sadashivrao Bhau, and the Nizam of Hyderabad, a powerful regional rival in the Deccan. This battle is noteworthy not only for its outcome but also because the Maratha forces employed modern European-style military tactics and weaponry, signaling a turning point in Indian military history.

The battle was part of a broader power struggle in the region following the fragmentation of the Mughal Empire, as the Marathas sought to expand their dominance across central and southern India. The conflict was driven by the Marathas' determination to assert their political and military supremacy in the Deccan and to enforce their rights to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi—taxes levied by Maratha rulers in return for providing protection—within territories controlled or contested by the Nizam. The battle took place near Udgir Fort at Khadakli area in the district, and resulted in a decisive Maratha victory. Following the defeat, the Treaty of Udgir was signed, forcing the Nizam to cede several key territories to the Marathas and marking a significant expansion of Maratha influence. This victory not only demonstrated the Marathas' growing military power but also served to further solidify Sadashivrao Bhau’s leadership in the years leading up to the Third Battle of Panipat. Udgir Fort, already of historical and religious importance, gained lasting prominence as the site of this critical Maratha triumph and the resulting treaty. The fort remained under the Marathas until 1818 when it was taken over by the Nizams and the British after the third Anglo-Maratha war.

Treaty of Udgir

Following the defeat, the Treaty of Udgir was signed. The Nizam was forced to cede several territories to the Marathas, including Ahmadnagar, Daulatabad, Burhanpur, and Bijapur, which according to the Osmanabad district Gazetteer (1972) were “worth sixty lakhs of rupees.” This victory consolidated Maratha authority in the Deccan and strengthened Sadashivrao Bhau’s leadership prior to the Third Battle of Panipat (1761 CE). The fort remained under Maratha rule until 1818, after which it came under the control of the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Battle of Palkhed and Maratha Revenue Rights

The early years of Nizam rule were marked by much contestation with the Marathas, who had been asserting their revenue rights across the Deccan region. In 1728, Peshwa Baji Rao I launched a swift campaign against Nizam-ul-Mulk, culminating in the Battle of Palkhed. The Marathas demanded the right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi (customary taxes) from six subahs of the Deccan—among them Aurangabad, which then included Dharashiv.

The Nizam’s defeat at Palkhed forced him to recognise Maratha claims over revenue collection. Though the region remained nominally under the Nizam, the Marathas began exercising real influence—stationing troops, appointing local agents, and intervening in administration. This influence became more visible in 1732, when Baji Rao personally travelled to Latur for negotiations at Rohe Rameshwar.

Maratha–Nizam Engagements in Tandulja and Udgir

Once the French were defeated by the English, Nizam Salabat Jung was left with a weak army and no alliances to support him. Again, the Marathas viewed this as a golden opportunity to capture more territory belonging to the Nizam.

In 1760, the Maratha army (consisting of 40,000 men) overpowered the Nizam’s army which consisted of only 22,000 men. This battle took place at Tandulja which now lies in the nearby Latur district. The fort of Udgir was completely surrounded by Marathas. The Nizams lost the battle and were forced to give up a lot of territory and subsequently the Naldurg and Udgir Fort fell into the hands of the Marathas.

The Nizam’s fortunes briefly reversed after the Maratha defeat in the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). After the death of Salabat Jung, his younger brother took over. In 1761, the Marathas fought the Afghan army in the battle of Panipat and suffered defeat. Nizam Ali decided that this was the perfect time to reclaim lost territories from the Marathas. He fought against the Maratha army in 1761 and won control of the Udgir fort. However, in 1763, when the Nizam attacked Pune, the Marathas defeated him. This time, the Nizam had to give away even more territory.

Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountcy

In 1790 CE, the Nizam, the Marathas and the British jointly defeated Tipu Sultan. His kingdom was divided between the Nizam, the Marathas, and the British. On 12 October 1800 CE, the East India Company signed a treaty with Nizam Ali to end its independence. The British army was permanently stationed at Secunderabad to protect the Nizam's kingdom.

After the death of Nizam Ali in 1803 CE, his son Sikandar Jahan became the third Nizam. This Nizam did not pay much attention to the affairs of the state. Moreover, the old diwan died and Chandulal became the new diwan. It was during this period that William Palmer, an Englishman, opened a firm called the Palmer Company in the Nizam's State. This firm imposed an interest rate of 25 percent on the loans to the Nizam through Chandulal. These debts started increasing. Eventually, the entire state went into the hands of the firm. The situation in all the districts of Hyderabad became critical due to the debt of the Palmer Company and the Latur district was no exception. The Nizam government and its officials were responsible for the chaos in the state and also in Latur district. Due to instability and unrest, Shivlingappa Deshmukh revolted at Udgir. In December 1820, a British officer Sutherland stormed with troops to destroy it.

According to the treaty of 1853, the Nizam gave the districts of Kahad, Naldurg, and Raichur to the British against the loan of the East India Company. In 1860 CE, the British again handed over these districts to the Nizam. The Naldurg district included most of the present Latur district. In 1870 CE, the Nizam's Prime Minister Salarjung I reorganized the districts in the state. In 1904 CE, the district was renamed as Osmanabad and its headquarters was shifted to Osmanabad. This included Vashi, Ausa, Kalamb, Tuljapur, Naldurg, and Osmanabad talukas. At that time, Latur was located in Ausa taluka. In 1905 CE, the headquarters of Ausa taluka shifted to Latur and a new taluka was formed.

Rohilla Raids and Suppression

The district played a significant role in the larger resistance movements against British colonial rule and the Nizam’s administration. At the time of the Revolt of 1857, also known as the First War of Independence. Around the same time, some parts of the district experienced raids by Rohillas, members of a Pashtun-origin community who had earlier established power in Rohilkhand (in present-day Uttar Pradesh). Following the collapse of rebellion in the north, bands of Rohillas migrated southward, looting villages along their route.

In February 1859, a group of approximately 150 Rohillas looted the village of Nelingah (present-day Nilanga, in Latur district, then part of Dharashiv). A combined force from the Hyderabad Contingent and British officers was sent in pursuit. Captain Murray (stationed at Udgir) and Captain Grant (at Gangakhed, Parbhani) led the operation, capturing the group near Udgir. Investigations revealed that the patels (village headmen) of Harali (which lies in present-day Dharashiv) had sheltered the Rohillas. Letters found in the village tied the incident to the larger conspiracy involving Safdar-ud-Daulah and other rebel sympathisers.

By the end of 1859, most signs of armed resistance in the region had been brought under control by the combined efforts of the British and the Nizam’s forces. As a gesture of recognition, a new treaty was signed in July 1860 (noted earlier). Through it, the districts of Raichur (now in Karnataka) and Dharashiv (which then included Latur) were returned to Hyderabad, and a loan of ₹50 lakhs owed to the British was formally cancelled.

Bhalki Conspiracy of 1867

Even so, traces of unrest remained. In 1867, nearly a decade after the uprising, the Bhalki Conspiracy unfolded which is often seen as the last major attempt to revive rebellion in Hyderabad State. It was led by Ram Rav, also known as Jung Bahadur or Madhu Rav, who claimed to be a descendant of the Maratha royal family and took on the title of Chhatrapati of Satara.

Between 1866 and early 1867, Jung Bahadur travelled through parts of Latur district, such as Nilanga (then part of the district). He issued appointment letters (kaulnamas), gathered followers, and raised funds through informal promissory notes (hundis), all while speaking openly of his intent to overthrow British rule in the Deccan. His circle of supporters extended to Ausa and Latur, where efforts were made to recruit men and collect weapons.

At one stage, he occupied a small fort at Ashti (in present-day Bidar district), hoisted a saffron flag, and declared it his base. Witness statements and letters recovered later from his associates showed plans to capture strategic towns such as Ausa, Udgir, and Naldurg. The documents also revealed appeals for military support sent to local landholders (patels and deshmukhs), some of whom responded with offers of men and money. Seals found on his papers bore the royal title “Chhatrapati.”

Eventually, Jung Bahadur and his associates were arrested near Bhalki. Their testimonies revealed a detailed and well-organised conspiracy, but the uprising was suppressed before it could begin. This event is widely viewed as the final echo of the 1857 rebellion in the region.

Arya Samaj

A branch of Arya Samaj started in 1891 CE at Gharoor (Beed) in Marathwada. Later, Arya Samaj was established at Gunjoti in Umarga taluka of the Dharashiv district. It promoted nationalism and social reforms. More branches of the Arya Samaj were established in almost all the districts. The death of one of the Arya Samaj activists in Latur gathered many people. The Arya Samaj also started libraries and gyms in Latur. The strengthening of the Arya Samaj contributed to the freedom of Hyderabad sansthan.

In 1905, Latur was officially given the title of Latur tehsil and was integrated with Osmanabad district. At that time, Osmanabad district was governed by the Nizam of Hyderabad and came under Hyderabad state. The two years 1937 and 1938 are considered to be very important in the freedom movement of Hyderabad and Marathwada. It was during this period that political thought gained stability and acquired a certain form. The first session of the Maharashtra Parishad was held on 1 June 1937 at Partur (now Jalna district). The convention was attended by Bhaskar Rao Naldurgkar and Dattatrayrao Laturkar from Latur District. The second session of Maharashtra Parishad was held on 1st and 2nd June 1938 at Latur. The Nizam government deliberately sent a contingent of police to Latur on this occasion.

At the end of 1938, provincial councils came to power in British India, but in the state of Hyderabad, the situation was serious. A huge satyagraha took place in the state of Hyderabad against the ban on the State Congress. It took place on the occasion of Diwali on 24 October 1938. The Satyagrahis from Latur were the first to go there hence Razakari suppression was rampant in the district and were carried out in many other areas. Consequently, many people started opposing the Razakars. Other important organized groups in this region were the Aryavir Dal and Kisanveer Dal. The Aryavir Dal struggled for Hattibet in Udgir taluka. Many soldiers of the Nizam’s army were killed in the battle of Hattibet on 27 September 1947.

Trade Importance

In the early 20th century, the district was a town in Ausa taluka of Osmanabad (now Dharashiv) district, Hyderabad State. It had a population of 10,479 in 1901 and played a vital role in the cotton and grain trade. The town was well-connected to Barsi railway station, 64 miles (103 km) away, facilitating commerce.

The district was a significant trade hub, as it was a key location for buying and selling goods in the region. According to the Imperial Gazetteer (1909), “the chief centre of commerce is Latur, from which almost the whole of the imported articles arc distributed throughout the [Osmanabad] District.”Further it says that “at Latur in the Owsa (present Ausa taluka), which is a large trade centre, a small ginning mill was erected in 1889, and two more have been started since 1901”.

The district’s role in trade and processing would have made it an important town in the district and in terms of cotton processing (separating cotton fibers from seeds) the district must have become an increasingly important industry in Latur over time. Given that these developments happened in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it reflects a time when cotton was a valuable commodity in India, especially under British colonial rule.

Maharashtra Parishad

The district played a significant role in the Maharashtra Conference, hosting key sessions in 1945 and 1946, which contributed to the growth of the political movement against the Nizam’s rule.

The second session of the Maharashtra Parishad Conference was decided to be held in Latur. According to the Gazetteer (1972), around 1937 to early 1938 as a time of heightened political activity and resistance in Hyderabad State, the session in Latur took place. The session was supposed to pass a constitution, but it was instead given up in protest due to disagreements.

The session was part of a broader resistance movement in Hyderabad State, where people started asserting their fundamental rights. Marathwada leaders and activists gathered in Latur as part of a larger movement demanding freedom of speech, press, and assembly, which were restricted under the Nizam’s rule.

It should be noted that the Maharashtra Parishad actively joined the Satyagraha movement against the Nizam in 1938, alongside the Hyderabad State Congress. Such activities in Hyderabad were viewed as a threat by both the Nizam and the British. This movement played a crucial role in mobilizing people in Latur, Osmanabad, and other parts of Marathwada, paving the way for future struggles that resulted in Hyderabad’s merger with India in 1948.

The Umri session of the conference debated adopting a constitution based on the principles of Responsible Government but ultimately delayed the decision due to political concerns. The 1945 session was successfully held at Sailu and the 1946 session in Latur city. Mr. D. G. Bindu and Mr. Waghmare presided over these sessions. These sessions marked a new phase of political awareness and the strengthening of the Maharashtra Conference's organization.

Post-Independence

After India gained independence in 1947, the princely state of Hyderabad, which included Osmanabad district (and with it, Latur), remained outside the Indian Union. This changed in September 1948, when the Indian government conducted Operation Polo, a military action that led to the formal end of Nizam rule and the integration of Hyderabad into India.

Administrative changes followed. In 1956, as part of the States Reorganisation Act, Osmanabad district was transferred from Hyderabad State to Bombay State, and later, with the creation of Maharashtra in 1960, it became part of the new state. Latur continued to exist as a taluka within Osmanabad district during this period.

For decades, it remained part of Osmanabad district. On 15 August 1982, Latur was officially carved out as a separate district, with its own administrative headquarters. This reorganisation was driven in part by local political leadership, including the role played by Vilasrao Deshmukh, a native of the region who later served as Chief Minister of Maharashtra.

Lift Irrigation Scheme in Latur, 1954

Many changes took place in the district after the post-Independence period. As part of the broader push for rural development in the post-integration period, several agricultural initiatives were introduced in Latur, particularly focusing on water access and cooperative farming.

One of the earliest of these efforts was launched in 1954, when a cooperative lift irrigation society was formed in Chikurda village, Latur taluka. It aimed to improve farming output by drawing water from a network of 30 wells, irrigating about 182 hectares of land.

To expand the coverage, the society brought another 76 hectares under cultivation. Though small in scale—with 36 members and a paid-up capital of just ₹515—it marked an important step in self-organised rural water management.

Government assistance followed in 1959, when the Revenue Department provided a loan of ₹89,600 to help farmers acquire 27 oil engines for water lifting. The initiative was part of a larger strategy to promote well-based irrigation and support smallholders through a cooperative model that emphasised shared effort and resources.

Latur as a Pilot Area for Joint Farming Societies, 1966

These early experiments perhaps set the stage for more structured efforts in the 1960s. In 1966, Latur was chosen as a pilot area to develop joint farming societies, a form of collective cultivation promoted by the state as a means of increasing productivity and rural cooperation.

By March 1966, nine societies had been established in Latur taluka, and another twenty-two across the district. Together, they brought 611 farmers under a shared structure, jointly cultivating over 5,356 acres of farmland.

Financially, the effort saw some success. The total paid-up share capital of these societies reached ₹78,786, including ₹27,835 in government contributions. A small reserve fund of ₹700 was also created. These collective efforts allowed farmers to share tools, labour, and knowledge, while also improving access to credit and government support.

Killari Earthquake, 1993

In the year 1993, Latur faced one of the most devastating events in its recent history. On the early morning of 30 September 1993, a 6.4 magnitude earthquake struck Killari village in Ausa taluka, causing widespread destruction. Though the region was not considered a high-risk seismic zone, the earthquake caused severe damage across 21 villages, including Sastur, Killari, and Mangloor.

The death toll was estimated between 3,000 and 4,000, and many more were injured or displaced. Homes made of white soil, common in village construction, collapsed easily, while kachcha houses in some cases remained standing. The earthquake occurred during Ganpati Visarjan, many people had returned indoors after festivities, which likely contributed to the high casualties. Survivors recalled that tremors had been felt in the region previously, but the scale of destruction in 1993 was unprecedented. Notably, initial confusion led many to believe the nearby Makhni Dam had burst.

Relief efforts were mobilised soon after. Survivors were relocated to permanent housing colonies, and several orphanages and old age homes were set up. Government agencies also provided food rations, drinking water, and financial compensation to affected families. In the years that followed, new construction in the region placed more emphasis on earthquake-resistant design.

Sources

District Census Hand Book – Latur.Census of India. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

Imperial Gazetteer Of India Provincial Series Hyderabad State. 1909.Superintendent Of Government Printing, Calcutta.

India Today. 2015.Maharashtra's deadliest earthquake: Some facts you must know about the Latur earthquake.India Today.https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk…

L.G. Rajwade ; G.A. Sharma; P. Setu, Madhava Rao et al. eds. 1972. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Osmanabad District. Govt. Press, Mumbai

Shyam Prasad. 2022. 12th-century Kannada inscription discovered in Maharashtra's Latur village. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ben…

Vijay Sathe. 2015. “Discovery of a Fossil Bone Bed in the Manjra Valley, District Latur, Maharashtra.” Vol 75,Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute.https://www.jstor.org/stable/26264717

Websites Referred:Digital District Repository, Latur District Website, Wikipedia.

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.