Contents

- Ancient Period

- Microlithic and Mesolithic Settlements along the Salsette Coast

- Kanheri and the Network of Buddhist Cave Sites

- The Mahakali Caves at Kondivite

- Mandapeshwar and the Shaiva Transition

- The Kalachuris and the Circulation of Krishnaraja’s Coinage

- Jogeshwari Caves

- Shilahara Rule in Salsette and their Patronage of Kanheri

- Naval Campaigns and the Eksar Hero Stones

- Curse Stones of the Shilaharas

- The Mysterious Ruler Bimb and his Capital at Mahim

- Koliwadas as the Oldest Settlements of Salsette

- Medieval Period

- Gujarat Sultanate

- The Treaty of Bassein (Vasai),1534

- Portuguese

- Franciscan Order in Salsette

- Emergence of the East Indian Communities of Salsette

- Defense Structures of the Portuguese

- Bandra Fort

- Madh Fort

- Trade Policy of the Portuguese

- Rise of the Marathas and Fall of the Portuguese

- Reclamation of the Mandapeshwar Caves

- Colonial Period

- Economic Interventions and Agrarian Experiments on Salsette

- Teak Plantation Scheme (c. 1810)

- Paddy and Cotton Cultivation

- Liquor Licensing and Local Revenue

- Causeway Construction and Connectivity with Bombay

- Railway Expansion and Suburban Growth

- The Bubonic Plague and the City’s Uneven Expansion

- Planning Segregation and The Bombay Development Committee, 1913

- Administrative Transformations and the Formation of Greater Bombay

- The Growth of Nationalist Sentiment in the Suburbs

- Revolutionary Networks and Popular Mobilisation

- Civil Disobedience and the Wadala Salt Depot (1930)

- The Quit India Movement in the Suburbs (1942)

- Polish Refugees at Bandra Barracks

- Post-Independence Era

- Sources

MUMBAI SUBURBAN

History

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

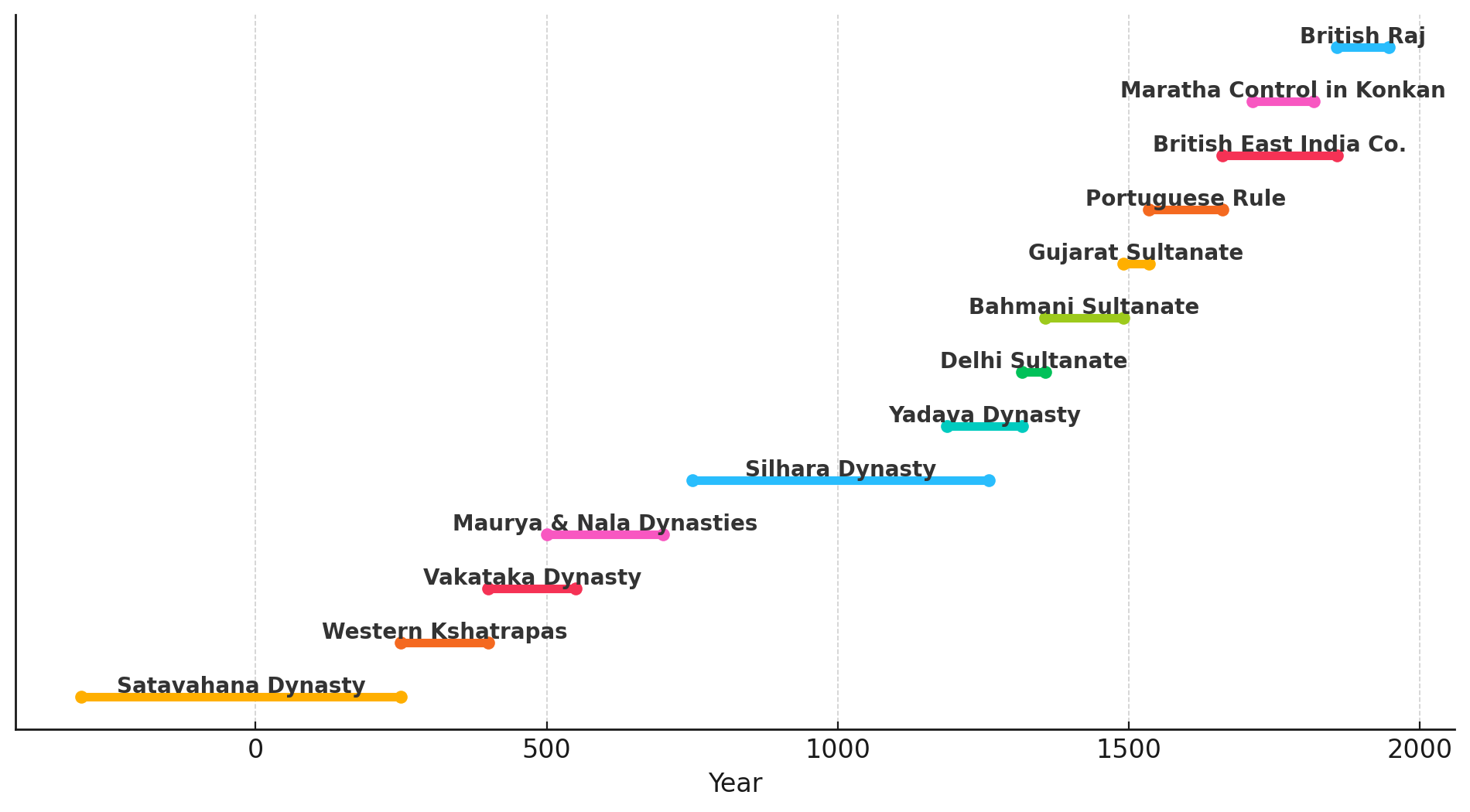

Mumbai Suburban District occupies the northern and north-western reaches of Salsette Island, within the wider Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Though it now bears the name of the great city to its south, its past is far older and rooted in the island on which it stands. Traces of human settlement here go back to prehistory, with microliths found near the lakes and streams. The most notable antiquities are the Kanheri Caves at Borivali where over a hundred rock-cut chambers were carved between the 1st century BCE and the 10th century CE. These caves served as a monastic complex for a Buddhist community that was supported, in part, by trade routes along the western coast of India.

Through the medieval and early modern periods, the district witnessed a succession of political influences. By the 16th century, Portuguese authority had taken root along the western seaboard, incorporating parts of Salsette into its sphere. Following a series of transfers and treaties, the island came under British control and eventually became part of the larger Bombay Presidency. In the decades following independence, the suburban areas of Salsette developed differently from the seven islands that form Mumbai City, and were eventually organised into three administrative talukas: Kurla, Andheri, and Borivali. Within these divisions, places such as Bandra, Versova, Malad, and Mulund underwent dramatic transformation, developing from agrarian or coastal hamlets into dense urban neighbourhoods through reclamation projects, planned infrastructure, and the pressures of rapid metropolitan growth.

Ancient Period

Microlithic and Mesolithic Settlements along the Salsette Coast

The earliest traces of human activity in what is now Mumbai Suburban district lie buried along the northern edges of Salsette Island, far removed in time from its contemporary urban landscape. It is in these parts—specifically near Manori Beach and the forested precincts around Tulsi Lake—that archaeologists have identified evidence of habitation reaching as far back as 30,000 years ago.

The most significant of these discoveries came to light through the Mumbai-Salsette Heritage Project, a coordinated effort led by the Centre for Extra Mural Studies (CEMS), University of Mumbai, in collaboration with the Archaeology Department of Sathaye College and the India Study Centre Trust. During fieldwork in the early 2000s, researchers documented both monoliths and microlithic tool clusters near Tulsi Lake, attributing them to the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic phases of human settlement. These finds included small, sharp-edged tools and cores, as well as lithic debris typically associated with on-site manufacturing—suggesting that the region was home to semi-permanent habitations or seasonal workshops in early times.

Another discovery came from the beach ridge at Manori which revealed one particularly valuable context. Here, archaeologists unearthed finished microliths, flaking debris, and tool cores which were tentatively dated to the Middle Stone Age (circa 10,000–15,000 years before present). These findings have led many scholars to believe that tool production took place locally, rather than being acquired through trade or collection. This suggests the presence of a settled or semi-nomadic population familiar with exploiting the marine and estuarine resources of the island.

Kanheri and the Network of Buddhist Cave Sites

If the microlithic settlements offer a glimpse into the region’s earliest human traces, it is in the basalt hills of Sanjay Gandhi National Park that one can find the clearest picture of organized religious and intellectual life in ancient Salsette. The Kanheri Caves, a vast monastic complex carved into the hills of Borivali, form the district’s most continuous archaeological record, spanning from the 1st century BCE to at least the 11th century CE.

The origins of cave architecture in Maharashtra are often traced to the Mauryan period, particularly the reign of Emperor Ashoka, under whom Buddhism received state patronage. As the religion spread westward, monastic establishments began to appear along key trade routes and elevated terrain across the Deccan. At this time, one of the principal centres of activity was the port of Sopara (identified with Nala Sopara, which lies in the nearby Palghar district), an ancient coastal town linked to Indo-Roman trade and Buddhist settlement. However, it is said that by the 1st century CE, Sopara had begun to decline. Silting of the harbour and changing trade patterns gradually reduced its importance as a maritime hub.

It was during this period that scholars say that the Kanheri Caves were first excavated, its growth tied to the decline of the Sopara. Monastic communities likely shifted inland in search of more sustainable locations. Sites like Kanheri situated near natural water sources and elevated terrain, offered suitable alternatives for continued religious life. Over time, the site grew into one of the largest and most enduring Buddhist cave complexes in western India. Its evolution, as documented in the Caves in MMR report, is typically divided into three major phases, shaped by changing dynasties, trade currents, and devotional practices.

The earliest phase, from the 2nd century BCE to the 4th century CE, corresponds to the Satavahana period. In this time, monks excavated simple viharas for residence and chaityas for worship. Notably, the earliest phase of construction at Kanheri is associated with the Satavahana dynasty, whose influence extended across western India between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE. In the Thane district Gazetteer (1896), it is noted that “of the six inscriptions which give the names of kings, one in cave 36 gives the name of Madhariputra and one in cave 3 gives Yajnasri Satakarni or Gotamiputra II”—both identifiable as Satavahana rulers. The architecture from this period is modest: clean-cut rock benches, prayer halls, and cisterns carved into the hill.

A second phase, stretching from the 5th to the 11th centuries CE, saw dramatic changes. Under the Traikutaka rulers and later the early Rashtrakutas, Kanheri expanded. Larger prayer halls appeared. Sculptural detail grew in complexity. Inscriptions proliferated, documenting the patronage of merchant guilds, donors, and local elites.

The final phase, from the 11th to 15th centuries CE, coincided with the rule of the Rashtrakutas and Shilaharas. While religious activity continued, it is noted that construction slowed, and the site gradually declined in prominence.

Interestingly, what many might not know is that Kanheri was not an isolated monastic establishment. It formed part of a broader network of Buddhist rock-cut cave sites distributed across the present-day suburban region of Mumbai. Notable sites in this cluster include the Mahakali (Kondivite) Caves, Mandapeshwar, Magathane, and Jogeshwari. The density and distribution of these sites suggest the long-standing religious and cultural importance of the region during the early historic and early medieval periods.

Archaeologist Manish Rai (2003) has drawn attention to the strategic placement of these sites. Their proximity to older Buddhist centres like Sopara, as well as trading ports such as Elephanta (in Raigad district, see Raigad for more) and inland junctions like Kalyan (Thane district, see Thane for more), points to deliberate monastic planning. This spatial pattern, in many ways, attests to the close association between Buddhist monastic institutions, trade, and commercial activity which was common during this period.

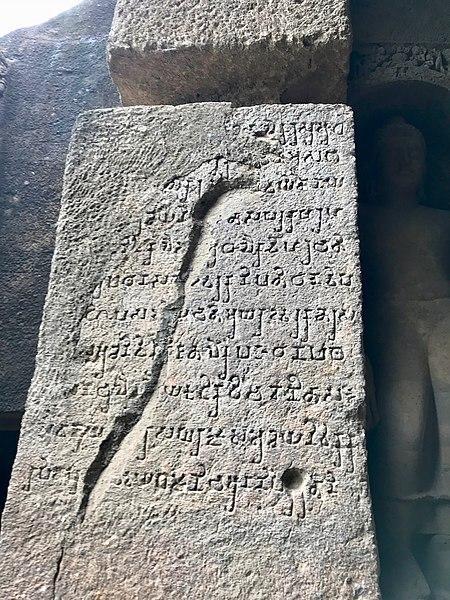

Inscriptions found at Kanheri support this view. The caves contain epigraphs in multiple scripts, including Brahmi, Pahlavi, and even Japanese. A 10th-century Pahlavi inscription is indicative of the presence of Parsi religious figures, while inscriptions in Japanese script point to contact with pilgrims or travellers from East Asia. These elements suggest that Kanheri functioned not only as a religious centre but also as a site of cross-cultural interaction.

The Mahakali Caves at Kondivite

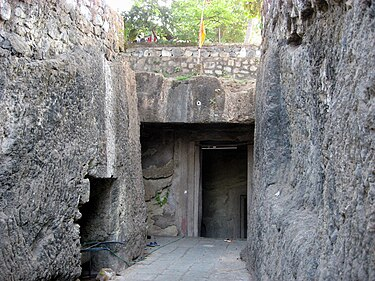

One of the satellite cave sites associated with Kanheri is the Mahakali Caves, also referred to as the Kondivite Caves, located in Andheri East on the slopes of Veravali Hill. Excavated between the 1st and 6th centuries CE, the site consists of nineteen caves, which are considered to have functioned as peripheral monastic spaces tied to the wider Kanheri complex.

A Pali inscription within one of the caves records a donation by Pittimba, a Brahmin of the Gotama gotra, situating the site within the social and religious patronage networks of the time (ASI).

The site, very significantly, appears to have been situated along early trade routes. Madhavankutty Pillai, in The Rock Chronicles (2023), writes that the Mahakali Caves likely lay along a corridor connecting coastal settlements with the interior. Archaeologist Kurush F. Dalal (2021) similarly identifies Mahakali as part of a broader network of trade-linked cave sites, active from the 3rd to 4th centuries CE.

Mandapeshwar and the Shaiva Transition

The Mandapeshwar Caves, located in Borivali near the banks of the Dahisar River, form another critical node in the district’s religious landscape. Dating to the late 6th century CE, they stand apart from earlier Buddhist caves in the region due to their explicit Shaiva iconography. Nevertheless, it is to be noted that the origins of the Mandapeshwar Caves remain debated. While the site is now known for its Brahmanical character, some scholars suggest that the earliest excavations may have served as Buddhist viharas.

Like the other cave sites across the region, Mandapeshwar is believed to have been positioned along ancient trade routes that once linked the western coastline with the Deccan interior. What distinguishes it, however, is scholars believe it may have served as a resting site for ascetics, pilgrims, and priests traveling to the nearby Kanheri Caves, which interestingly, some say, functioned as a major religious and educational centre during that period.

The Kalachuris and the Circulation of Krishnaraja’s Coinage

Amid the religious architecture and donor inscriptions of early Salsette, the name of Krishnaraja, ruler of the early Kalachuris, surfaces in the region; his presence not found in monuments or inscriptions, but in coins. The Gazetteer of Greater Bombay (1909) records the discovery of coins issued under his reign in the area, dating them to the late 5th century CE.

These coins carry inscriptions in the Brahmi script and are marked with distinct punch symbols. What makes them particularly significant is their wide geographical spread. Similar coins have been found not only in Mumbai but also in parts of northern Rajputana, southern Maharashtra, and eastward into Vidarbha. Their dispersal suggests that, by this time, there was a functioning network of trade that linked the Konkan coast with the interior regions of the subcontinent.

Jogeshwari Caves

It was during the Kalachuri period that the Jogeshwari Caves—a set of rock-cut monuments located in the present-day suburb of Jogeshwari—are believed to have been excavated. Carved into basalt, the site is considered one of the earliest surviving examples of Hindu cave architecture in the Deccan region. It also marks a critical phase in the religious transformation of the area, reflecting the transition from Buddhist to Brahmanical patronage.

The Kalachuri dynasty is known to have supported the Pashupata sect of Shaivism. Under Kalachuri influence, several Shaiva shrines were established across the region, with Jogeshwari widely considered among the earliest and most influential.

Historian Walter Spink memorably called Jogeshwari the “grandfather of all” Hindu cave temples. This is not merely due to its antiquity, but to the architectural vision it helped inaugurate. The cave’s central sanctum, aligned hallways, and early Shaiva iconography would, most notably, influence later cave-temple forms at Elephanta and Ellora.

Shilahara Rule in Salsette and their Patronage of Kanheri

Following the Kalachuris, political authority in Salsette passed into the hands of the Shilaharas of Konkan, a regional dynasty who initially ruled as tributaries under the Rashtrakutas of Malkhed. The earliest records of Shilahara control in the district appear in two dated inscriptions from the Kanheri Caves—Shaka 775 (853 CE) and Shaka 779 (877 CE)—which confirm their dominion over Salsette, Thane, and surrounding areas. According to the Thane district Gazetteer (1896), "only two of the inscriptions, however, contain dates... They belong to the Silhara kings of the Konkan, who were tributaries of the Rashtrakutas of Malkhed.”

Between the 8th and 13th centuries CE, the Shilaharas emerged as significant cultural patrons in the region and played a defining role in shaping Salsette's religious and educational institutions. Their support for Kanheri’s continued development during the 9th century is among the most notable examples of this legacy.

The Shilaharas retained effective local control until the mid-12th century. In 1161 CE, the Solanki kings of Gujarat launched a campaign against the lucrative port city of Bombay, defeating the Silhara ruler and temporarily occupying Thana and Bombay. However, by 1187 CE, the Silharas had regained control, re-establishing regional stability for several decades.

Naval Campaigns and the Eksar Hero Stones

Among the most remarkable archaeological remains from the Shilahara period in Mumbai Suburban are the Eksar Veergals—carved memorial stones located in Eksar village, Borivali. Dating to between the 9th and 13th centuries CE, these stones belong to a broader tradition of Veergals (hero stones) found across Maharashtra and parts of South India, commemorating individuals who died in battle or in acts of sacrifice.

A typical Veergal follows a tripartite format: the lower panel illustrates the battle scene, the middle shows the hero ascending to the afterlife or offering worship, and the top often bears a pot or jar, symbolising amrit—the nectar of immortality. In the case of the Eksar stones, however, a distinct variation appears. Rather than land battles, these panels depict naval engagements—complete with carved ships, marine combatants, and warlike scenes at sea.

This motif is extremely rare in the corpus of Indian hero stones. Aarefa Johari (2012) commenting on the Eksar Veergal writes, "these war memorials, made of flat basalt tablets ranging from four to eight feet in height, are an unusual and significant representation of maritime heritage within the broader tradition of hero stones." The Eksar Veergals therefore offer not only a record of military valor, but a rare visual document of coastal warfare during the Shilahara era.

Curse Stones of the Shilaharas

Another class of medieval relics found in the district is the Gadhegal, also known as the “ass-curse stones,” many of which are associated with the Shilahara period. These carved basalt slabs, often depicting a donkey and a woman in a sexually explicit pose, were historically used to mark land grants and territorial boundaries. Their grotesque imagery functioned as a visual threat, a curse intended to deter violations of royal or feudal orders.

Kurush Dalal, an archaeologist and historian, explains that these stones typically accompanied declarations of land grants, especially those issued to Brahmin or feudal recipients. The explicit scene symbolised the shame or supernatural punishment awaiting anyone who breached the agreement. A number of these stones survive in the present-day Mumbai Suburban district. Noteworthy among them are examples enshrined at the Sati Mata Mandir within Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and another at a Mhasoba shrine in Bhandup. These are a few among many. Their presence indicates, above all, the existence of an authority with the power to grant land during the period—and the wide territorial extent over which that authority was recognised.

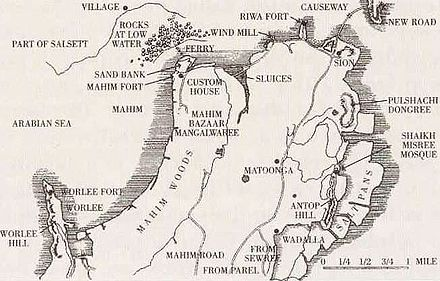

The Mysterious Ruler Bimb and his Capital at Mahim

Following the decline of the Shilahara dynasty in 1265 CE, when their last known ruler, Someshwar, was defeated and killed by Mahadeva Yadava of Devagiri, the northern Konkan—including the islands of Salsette and Mahim—briefly came under Yadava control. While the Bombay City Gazetteer (1909) suggests that the Yadavas ruled this region from roughly 1260 to 1300 CE, little administrative or architectural evidence survives from their presence in present-day Mumbai Suburban district.

Later, the North Konkan region, including parts of present-day Mumbai Suburban district, appears to have come under the control of a local dynasty associated with a figure known as Raja Bimba. While the precise historical origins of Bimba remain debated, later records such as the Mahikavatichi Bakhar—compiled between 1448 and 1578 CE—suggest that he was a ruler of Gujarati origin, possibly from the house of Patan, who extended his control southward along the western coast.

It is believed that Bimba’s territory included much of the modern Mumbai Metropolitan Region, including areas such as Malad, Marol, and Deonar, which today are part of the Mumbai Suburban district. The capital of his kingdom, known as Mahikavati, was located at Mahim, and served as the administrative and trading centre of the region. Suburban locations such as Marol and Malad were governed by local administrators (Desais), pointing to a feudal system of provincial governance that existed under Bimba’s rule.

The political importance of Mahim is also reflected in later inscriptions. A 1368 CE stone epigraph discovered in Deonar refers to “Mahim Bimbasthan,” indicating that the memory of Bimba’s rule persisted for at least two centuries. This inscription also names King Hambirrao, a subordinate of Firuz Shah Tughlaq, suggesting that the region had by then come under the control of the Delhi Sultanate, but continued to be identified by its earlier dynastic legacy.

Trade, salt production, and port activity appear to have flourished under Bimba’s administration. Mahim functioned as an active port, with references to salt pans in Khar, while other suburban areas such as Juhu, Chembur, Mulund, Bhandup, and Aarey are mentioned in the chronicle as settled villages of the time. These accounts, while preserved through a mixture of literary and inscriptional sources, offer a glimpse into the urban, economic, and administrative landscape of the suburban tract before the rule of the later medieval dynasties and colonial powers.

Koliwadas as the Oldest Settlements of Salsette

Long before the rule of Bimb or any of the dynasties who held sway over the region, the lands of Salsette and the seven islands that now form Mumbai were home to the Kolis, a fishing community widely regarded as the earliest known inhabitants of the area.

Their presence here stretches back at least two thousand years, with some accounts placing their arrival as early as 600 BCE. While these estimates vary, what is certain is that by the time the region begins to emerge in epigraphic and literary records, the Koli settlements, known as Koliwadas, were already established along the coast, each a modest cluster of dwellings near tidal creeks or sheltered bays.

Several such names endure to this day: Khar Danda, Vazira Koliwada, and Bandarpakhadi, among others, preserving both the nomenclature and, in places, the connections to their traditional occupation. Despite the many political changes that swept through Mumbai over the centuries, the Koliwadas of Salsette have endured. They are among the oldest living settlements in the district and stand as a testament to a way of life that connects modern Mumbai to its coastal origins.

Medieval Period

Gujarat Sultanate

Up until now, it has been established that in 1300, much of the present-day Mumbai City and Suburban districts were under the control of Raja Bimb. Historical records offer little detail on his eventual passing, but it likely occurred in the early 14th century. After his demise, his son ascended the throne, though the exact date remains obscure.

The next well-recorded event in the history of this area happens in 1318 CE. At that time, Mubarak Shah I, son of Sultan Alauddin Khilji of Delhi, led a military campaign and took control of regions including Salsette (present-day Mumbai Suburban district and parts of Thane).

To understand these changes, it’s helpful to look at the broader context. During this time, the Delhi Sultanate was ruled by the Tughlaq Dynasty. The Tughlaqs focused mostly on defending their mainland territory in northern and central India, and they often neglected the small islands along the western coast. As a result, local chiefs and rulers seem to have kept practical control over areas like Mumbai Island (present-day Mumbai City) and Salsette. The Bombay Island Gazetteer (1909) mentions that this local control continued until the rise of the Gujarat Sultanate in the early 1400s.

The Gujarat Sultanate started in 1407, when Zafar Khan, the Tughlaq governor of Gujarat, declared his independence and became known as Muzaffar Shah I. He took control of Gujarat, Salsette, and Mahim (present-day Mahim, Mumbai City). During this period, other regional dynasties were also coming up, and the Delhi Sultanate was growing weaker. This led to many struggles for control, especially over the islands around Mumbai, with conflicts between the Gujarat Sultanate and its neighbours continuing up to 1432.

One significant episode took place during the rule of Sultan Mahmud Shah I (1458–1511) of Gujarat. According to the Gazetteer of Bombay Island (1909), which refers to the Persian historical text Mirat-i-Sikandari, the Sultan led an attack on some “Firangis” (foreigners) who were creating trouble in Mahim (Mumbai City). These “Firangis” were, in fact, the Portuguese, who had just begun to establish themselves in the region—especially in Bombay, Salsette, and Bassein (present-day Vasai, Palghar district).

Although Mahmud Shah I managed to drive out the Portuguese for a time, their attacks on Mahim continued. In 1516, a Portuguese commander, Dom João de Monoy, entered Mahim Creek and captured Mahim Fort (in today’s Mumbai City) from its defenders. The fort became the site of repeated fights between the Portuguese and the Gujarat rulers, until 1534, when Bahadur Shah of Gujarat was forced to hand over Mahim and other islands to the Portuguese. From then on, the Portuguese were able to control most ports along India’s western coast, from Diu (in present-day Gujarat) down to Goa. This marked the start of Portuguese rule in Bombay (Mumbai).

The Treaty of Bassein (Vasai),1534

The treaty of Bassein was signed by Bahadur Shah of Gujarat and the kingdom of Portuguese in 1534, as the Sultanate of Gujarat could not sustain constant attack from the Portuguese. The treaty allowed Portuguese control over Vasai islands and seas including Mumbai. Thus by 1534, modern Mumbai, Vasai, Virar, Daman & Diu, Surat and entire Goa had gone in the hands of the Portuguese. This treaty marked the beginning of Portuguese rule over the present-day district.

Portuguese

From the early 16th century, the Portuguese desired to annex Salsette Island and the Bombay archipelago. This ambition resulted in acts like seizing vessels of the Gujarat Sultanate in Mahim Creek (also called Bandra Chi Khadi) in 1509 among many other attacks. Their relentless pursuit finally turned fruitful in 1534 when the Sultanate ceded the territories. In 1661, the seven islets which make up today’s Mumbai City were ceded to Britain as part of the dowry of Catherine de Braganza to Charles II of England; while Salsette remained in Portuguese hands.

This event marked a turning point for Salsette. The Portuguese, known for their policy of religious governance, caused significant changes to the island's social fabric. When it comes to administration, the Portuguese employed a unique system in the wider North Konkan region. Territories were divided into "fiefs," essentially landholdings granted by a superior to a subordinate. Following this system, Salsette was leased to explorer Diogo Rodrigues from 1535 to 1548, before being handed over to Garcia de Orta in 1554.

The Portuguese, following their arrival on the western coast of India in the early 16th century, pursued an explicit policy of religious expansion alongside trade. This dual agenda is encapsulated in Vasco da Gama’s statement, “Vimos buscar Christaos e especiaria” (We come to seek Christians and spices). In the territories under their control, especially on Salsette Island, the Portuguese encouraged conversion to Roman Catholicism primarily through the activities of two religious orders—the Franciscans and the Jesuits.

Franciscan Order in Salsette

Among the earliest and most active Catholic orders in the region were the Franciscans, led by António do Porto. From 1547 onward, they began establishing churches across Salsette. By 1585, the order had not only built religious institutions but had also gained considerable control over the island. According to Gerson da Cunha, they had founded at least eleven churches and a college in Bandra by the end of the 16th century.

Yet the process came at a cost. The Gazetteer of Greater Bombay notes that many Roman Catholic clerics amassed vast wealth, even surpassing the revenues of the Portuguese Crown in India. Their political influence and public displays of affluence created growing unease, even among colonial administrators.

With the spread of Christianity came the systematic conversion or destruction of earlier religious sites. Several Hindu temples and caves were either demolished or appropriated for Catholic use. The Mandapeshwar Caves in Borivali (mentioned above) were among the partially dismantled sites. The Portuguese intended for it to become the Church of Nossa Senhora da Piedade in 1549. According to the Thane District Gazetteer (1882), the site was renamed Montpezier (or Monpacer) and converted into a church and college complex. During this period, original carvings were damaged or removed, masonry additions were built, and a stone cross was engraved into one of the cave walls—marking a phase of Christian occupation.

Of the churches established by the Franciscans, those still in use include St. Andrew’s Church and Mount St. Mary’s Church in Bandra and remnants of churches in Santa Cruz.

The Bombay Gazetteer (1909) notes that large-scale conversions during this period, often under coercion. António do Porto is credited with converting more than 10,000 people and with destroying up to 200 mandirs, while commissioning the construction of over a dozen churches. Religious institutions, including orphanages and seminaries were established to train a native Catholic clergy.

Emergence of the East Indian Communities of Salsette

A portion of this converted population over time developed a distinct cultural identity. Originally referred to as Indo-Portuguese, these communities formally adopted the name “Bombay East Indians” in 1887 with the formation of the Bombay East Indian Association (BEIA). This nomenclature aimed to distinguish them from later Catholic migrants from Goa and Mangalore.

The East Indians have lived in the region for over 400 years. They trace their ancestry to local agrarian groups who were converted to Roman Catholicism during the Portuguese colonial period (c. 1510–1739). Their cultural practices reflect a blend of indigenous and colonial influences, shaped over generations of settlement in the Mumbai region.

While much of their agricultural land has been lost to urbanisation, many traditional East Indian settlements remain; their architecture reflecting this blend in their culture. Areas such as Ranwar in Bandra retain distinctive features: narrow winding streets, low-rise bungalows with Mangalorean tiles, timber frames, and carved eaves. Portuguese-style oratories, village squares, and parish churches remain important elements of community life.

Defense Structures of the Portuguese

The spread of missionary activity and conversion efforts across the island was paralleled by the construction of a defensive infrastructure designed to safeguard maritime access and check rival powers.

Bandra Fort

Bandra Fort, known in Portuguese records as Castella de Aguada, was among the most significant of these. Strategically located at the southern tip of Salsette, it provided a commanding view over Mahim Bay, the Worli islands, and the northern entrance to the Mumbai harbour. Equipped with seven cannons and auxiliary artillery, the fort was a critical surveillance and defense post for vessels navigating the western coast.

Madh Fort

Further north, Madh Fort was constructed in the 17th century as a coastal watchtower overlooking Marve Creek. Its seven-sided structure remains largely intact, although the interior has suffered from neglect. Today, the fort falls under the control of the Indian Air Force and remains closed to the public. The surrounding area, however, continues to be inhabited by the Koli community.

Trade Policy of the Portuguese

While missionary activity defined the social fabric of Portuguese Bombay, trade remained the foundation of their imperial strategy. According to historian Sifra Lentin (2021), Portuguese ambitions in the Indian Ocean were driven by a desire to redirect the spice trade away from its traditional Mediterranean terminus at Venice.

At the turn of the 16th century, the Portuguese attempted to dismantle long-standing networks linking Arab, Ottoman, Persian, and Indian ports to Europe. With superior naval technology and artillery, they captured key coastal outposts and disrupted spice flows to Alexandria and Beirut. Between 1501 and 1506, Venice’s spice imports fell sharply—pepper shipments dropped from over 600 tons to just 135.

Yet these gains proved temporary. Despite controlling multiple ports along the Indian Ocean littoral, the Portuguese Crown failed to turn its seaborne empire into a sustainable economic venture. According to the Bombay Gazetteer (1909), the high cost of maintaining military and missionary establishments drained revenues. Moreover, religious expansionism alienated local merchants and restricted the scope of permissible commerce. In the present-day Mumbai region, Portuguese trade became largely confined to the export of dried fish, coconuts, and salt.

Rise of the Marathas and Fall of the Portuguese

By the 1730s, Portuguese control over Salsette began to erode as Marathas started vying for control over the region. When Peshwa Bajirao’s request for a Maratha trading post on Salsette was denied, and his envoys insulted, hostilities escalated. Bajirao assigned his brother, Chimaji Appa, to lead a campaign against the Portuguese.

In 1737, Maratha forces captured Thane and Salsette. Two years later, they laid siege to Bassein (present-day Vasai). Following a sustained assault, the Portuguese garrison was overwhelmed. The fort’s defences were breached, and the Portuguese garrison was defeated. The fall of Bassein, in many ways, marked not only a military victory but also the collapse of Portuguese political authority in the region. Control of the Mumbai suburbs passed into Maratha hands.

Reclamation of the Mandapeshwar Caves

In the 16th century, as mentioned above, under the Portuguese, the Mandapeshwar Caves were converted into a Christian place of worship. The site was then, as mentioned in the Thane gazetteer (1882), incorporated into a church and college complex known as Montpezier (or Monpacer).

In 1739, a few years after the Maratha conquest, the site was reclaimed and once again referred to as Mandapeshwar. A Marathi inscription in Devanagari script was added to mark this moment. The use of the site during this period reoriented it once again toward Shaiva pooja.

During the British colonial period that followed, however this changed. Christian use of the caves appears to have continued, though the specific nature and extent of such use remain unclear. The shifting religious and political uses of the site have led many to regard Mandapeshwar as “perhaps [having] the most tumultuous history of all the Mumbai caves.”

Colonial Period

In the latter half of the 18th century, the British East India Company began expanding its influence across the western coast of India, amid growing friction with the Maratha Confederacy. The island of Salsette, forming the bulk of what is today the Mumbai Suburban district, was then under Portuguese control but had declined significantly in administrative and economic importance. Recognizing its strategic location—flanking the commercially vibrant Bombay islands to the south which were under their control—the British sought to bring Salsette under their control.

Their first opportunity emerged during the First Anglo-Maratha War (1775–1782), when shifting alliances and territorial contests disrupted the balance of power in the region. As negotiations progressed toward a settlement, the British pressed for control over key coastal tracts.

The formal transfer of Salsette to the British was sealed under the Treaty of Salbai, signed on 17 May 1782. Concluded between the Maratha Confederacy and the British East India Company, the treaty marked the end of the First Anglo-Maratha War. Under its terms, the British secured several critical concessions, including:

- Full possession of Salsette Island, including the forts and former Portuguese territories therein

- Control over Bharuch, another key coastal town which lies in Gujarat

- A mutual agreement to prevent French influence in Maratha territories

- Recognition of British dominance over former Portuguese enclaves previously captured during the war

The treaty ushered in a period of relative peace between the British and the Marathas, though underlying tensions remained unresolved. For the British, the acquisition of Salsette was of lasting significance. It not only extended their territorial base around Bombay (Mumbai City) but also enabled the planned development of an urban hinterland to support the city’s commercial ambitions.

Following their acquisition of Salsette Island through the Treaty of Salbai (1782), however, the British East India Company was confronted with a pressing question: how to populate and economically revive an island that had suffered decades of neglect. To stimulate growth, the Company initiated a strategy of targeted immigration and administrative consolidation. The goal was to attract industrious communities that could help develop Salsette into a stable and economically viable hinterland to the expanding city of Bombay.

Among the first communities courted by the British were the Parsis, already prominent in Bombay for their roles in trade, administration, and emerging industry. Company correspondence from the period describes them as “a very industrious and quiet people,” ideal for settling in the newly acquired territory.

To operationalize this policy, the Company appointed Kavasji Rustomji as Patel (village head) of several villages in Salsette. Rustomji’s appointment was not symbolic—he actively facilitated Parsi migration to the district, helped administer new settlements, and liaised with Company officials to ensure infrastructural and agricultural progress. Under his leadership, the Parsi presence in the area expanded significantly, particularly in villages adjacent to Bombay’s northern edge.

By 1825, the effects of this migration policy were visible. The British cleric Rev. Reginald Heber, during his travels through western India, estimated the population of Salsette to be around 50,000—a notable increase considering the island’s condition four decades earlier. Hindus formed the majority of the population, followed by Muslims, Christians, Parsis, and smaller groups. This emerging ethnic and religious diversity perhaps laid the foundation for the later cosmopolitan character of Mumbai Suburban.

Economic Interventions and Agrarian Experiments on Salsette

The British East India Company also undertook several efforts to revive the island’s economy. With large tracts of government land and a growing population of settlers, officials aimed to introduce new crops, regulate trade, and generate revenue.

Teak Plantation Scheme (c. 1810)

One of the earliest initiatives was the promotion of teak cultivation. Bombay’s construction industry had a growing demand for timber, and Salsette offered a convenient supply base. In 1810, the Company launched a plantation drive using government lands.

Letters from the Collector of Salsette urged landowners to participate, noting the Governor’s “ardent desire” to promote teak. Saplings were planted during the monsoon season. The effort had lasting ecological impact—teak remains a prominent tree species in the region, especially in the present-day Sanjay Gandhi National Park.

Paddy and Cotton Cultivation

N. Benjamin (2003) in his writings mentions that with control over Salsette, the British government explored various crop possibilities besides teak. While Paddy was the staple crop during this time period, records indicate attempts to cultivate cotton. However, surviving letters exchanged by Bombay governors suggest these efforts likely petered out over time. Notably, historical accounts portray a thriving agrarian economy under Portuguese rule, sufficient to meet both Salsette’s needs and supply Bombay. This prosperity seemingly declined under British administration. Despite rice being the island's staple crop, production wasn't enough to sustain the local population.

Liquor Licensing and Local Revenue

Toddy and arrack production formed a major part of the local economy for many years. The British, under their administration, issued licenses to control quality and collect excise revenue. Vendors selling poor-quality liquor were penalised. Despite regulation, addiction and illegal brewing were ongoing concerns noted in administrative reports.

Causeway Construction and Connectivity with Bombay

One of the most significant interventions by the British in Salsette was the construction of causeways linking the suburban tracts with the island of Bombay. Prior to these developments, much of the region remained accessible only by ferry or seasonal routes, restricting movement of goods and people between the emerging colonial city and its hinterland. The earliest of these undertakings was the Sion Causeway, completed in 1803 under the direction of Governor Jonathan Duncan. It provided the first permanent land connection between Bombay and Salsette, replacing the earlier reliance on boats across the Mahim Creek.

Subsequent projects extended this system of links. The Mahim Causeway, completed in 1845, was financed largely through the philanthropy of Lady Avabai Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, wife of the Parsi merchant Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy. This structure connected Mahim with Bandra, facilitating uninterrupted access across tidal waters. The Kurla Causeway, laid out in the mid-19th century, further integrated the eastern side of Salsette with Bombay by connecting the growing industrial settlements along the creek. Together, these causeways not only enabled suburbanisation but also consolidated Bombay’s role as the administrative and commercial centre of the Presidency.

The improved connectivity contributed to changes in land use across Salsette. Agricultural villages were increasingly drawn into the city’s orbit, providing both labour and produce for the growing metropolis. Over time, the causeways served as the foundation for railway alignments and road networks, embedding the suburban district more firmly within the urban expanse of Bombay.

Railway Expansion and Suburban Growth

The integration of the present-day Mumbai Suburban district into the wider metropolitan framework of the British was greatly accelerated by the advent of the railway. As early as 1844, efforts began to acquire land across Salsette Island for a new mode of travel that would reshape the region. By 1853, these efforts culminated in the launch of India’s first passenger train, which departed from Bori Bunder (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus) and arrived in Thane, traversing the eastern corridor of Salsette. This 34-kilometre route inaugurated not only railway travel in India but also suburban connectivity in Bombay.

To make this possible, engineers constructed a series of viaducts linking Bombay Island to the Salsette mainland, transforming the movement of goods and people. With these new connections in place, affluent merchants and trading families began relocating to Salsette, establishing villas and estates in the emerging suburban tract. The 1901 census recorded a population of 1,46,993 in this area—an early sign of what would become Greater Bombay.

The Bubonic Plague and the City’s Uneven Expansion

Another thing that adversely affected Salsette—and, in the long run, led to the creation of Mumbai Suburban district—was the bubonic plague. The outbreak reached Bombay in September 1896. What followed was a period of fear, government intervention, and rapid social movement. Municipal officers began forcibly removing suspected patients from homes. Riots erupted in textile mill districts and people fled.

This flight from the city caused a visible northward shift. Many of those leaving Bombay sought space in the outskirts—especially in areas along the rail lines cutting through Salsette. What had been weekend retreats or seasonal shelters slowly became year-round settlements. The British administration responded by setting up the Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT), which encouraged development beyond Mahim, pushing deeper into Salsette.

The expansion, however, was uneven. Upper-class families were allotted planned plots in western suburbs like Bandra, Juhu, and Andheri (which all lie in the present-day Mumbai Suburban district). These became “respectable” zones with bungalows, open space, and civic services. Working-class migrants had fewer options. Some settled in temporary camps in Dadar, Sion, and Matunga (all lie in Mumbai City). Others moved further along the tracks—north to Kurla, Ghatkopar (both of which lie in Mumbai Suburban district), or even beyond. These locations grew not by design, but out of necessity.

Planning Segregation and The Bombay Development Committee, 1913

By 1913, when the Bombay Development Committee mapped out a plan for city expansion, the patterns were already clear. The western parts of Salsette were marked as residential and middle-class. The northeastern zones—Mulund, Vikhroli, Bhandup—were designated for industry. Factories and so-called “offensive trades” were located here. This divide, drawn on paper, was reinforced by the railway system. Suburban stations became gateways: some to opportunity, others to overcrowding.

The demographic and infrastructural patterns set during this period, in many ways, laid the foundation for the contemporary geography of the Mumbai Suburban district. What began as a public health response to a city in crisis evolved into a framework for urban expansion—albeit one marked by disparity in planning, services, and access.

Administrative Transformations and the Formation of Greater Bombay

Over time, the administrative boundaries of the region evolved alongside these developments. In 1920, Salsette Island was divided into two administrative divisions: North Salsette and South Salsette. North Salsette became part of the Thane district, while South Salsette was carved out to form what is now known as the Mumbai Suburban district. This marked the official establishment of the district as a separate administrative entity.

In 1939, acknowledging the growing urbanization in the suburbs and the subsequent rise in crime, the government took a crucial step. It sanctioned the amalgamation of a large part of the Bombay Suburban District with Bombay City for police administration. This move created a single, unified police force for the entire metropolis, transforming the Bombay City Police into one of the largest police forces in the British Empire, second only to the London Metropolitan Police.

The Growth of Nationalist Sentiment in the Suburbs

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the early stirrings of nationalist sentiment began to grow in the Mumbai Suburban district. The growing concentration of textile mills, printing presses, dockyards, and engineering workshops attracted a substantial working-class population. Within this emerging industrial belt, ideas of self-rule and anti-colonial resistance began to circulate, especially through trade unions and local associations.

Festivals such as Ganesh Chaturthi and Shivaji Jayanti, which had already been repurposed in the city for patriotic expression, gained similar significance in the suburbs. Local organisations such as the Dadar Brahman Sabha and the Shri Vile Parle Kelavani Mandal (SVKM), established during the Swadeshi period, promoted nationalist education and civic awareness among the youth. Vile Parle, in particular, would later develop into a prominent educational hub in the post-independence period.

Revolutionary Networks and Popular Mobilisation

By the 1920s, the district had become a discreet but active node for revolutionary activity. The layout of suburban chawls and small printing presses allowed for underground political work. Pamphlets, handbills, and bulletins critical of colonial rule were printed and circulated across Bombay from the suburbs. Newspapers such as The Bombay Chronicle, Times of India, and The Mouj served both as conduits for nationalist thought and platforms for public critique of government policy.

Women were active participants in these developments. Suburban residents took part in strikes, boycotts of imported goods, and public fundraising efforts. Among them was Usha Mehta, who would later gain recognition for operating a clandestine radio transmitter during the Quit India Movement, providing updates on Congress actions and police crackdowns.

Civil Disobedience and the Wadala Salt Depot (1930)

By the end of the 1920s, the political climate across India had begun to shift decisively toward mass civil resistance. The colonial government’s monopoly on essential goods, especially salt, had become a symbol of deeper grievances. In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi’s Salt March set the tone for local campaigns across the country. One such site of protest was the Wadala Salt Depot, located on the eastern edge of what is now the Mumbai Suburban district.

At that time, Wadala was not yet fully urbanised, but it held strategic importance. The depot stored large quantities of government-controlled salt—making it a natural target for satyagrahis (nonviolent resisters). Beginning in May 1930, groups of volunteers began marching to the depot with the aim of collecting salt in defiance of British law. On 22 May, 188 participants were arrested. They were sent to the Worli detention camp, which had been set up to manage the growing number of protestors.

What followed was an even more determined act of resistance. On 1 June 1930, nearly 15,000 volunteers, including women and children, marched toward the depot. They crossed muddy ground and pushed past police barricades to reach the salt pans. This was not a violent clash, but a coordinated act of noncooperation. Still, the authorities responded with force. Many were beaten, and thousands were arrested. The Worli camp, already under strain, recorded over four thousand detainees following the incident. The protests at Wadala made national headlines. For many, the image of ordinary citizens wading through slush to pick up handfuls of salt was powerful and reports of violence against peaceful demonstrators drew widespread public condemnation and strengthened support for the national movement.

The Quit India Movement in the Suburbs (1942)

The Quit India Movement of August 1942 saw the suburban tracts of Bombay become active sites of protest and sabotage. According to official reports, local leaders framed this final push as a decisive and potentially violent phase of resistance. Shankarrao Deo, addressing a Bombay audience, warned that Gandhi would emerge as a bāgī (rebel), ready to discard non-violence if independence could not otherwise be achieved.

Mill workers in the suburbs went on strike, paralyzing industrial operations. The railway network, crucial to the colonial economy, was disrupted by targeted acts of obstruction. In response, it is said that British authorities imposed severe punitive measures. Many activists were detained without trial, and press activity was heavily censored or shut down altogether.

Polish Refugees at Bandra Barracks

Amid the final decade of British rule, the Suburban region of Bombay found itself momentarily connected to the broader events of the Second World War. Among the lesser-known developments that took place during this period was the temporary establishment of a Polish refugee settlement at Bandra, where a section of the military barracks was repurposed to accommodate war-affected civilians from Europe. Here, several hundred Polish children, orphaned or displaced by the Nazi invasion of Poland and the subsequent upheavals across Eastern Europe, were received and temporarily settled.

Their journey to Bombay was neither swift nor simple. Many of the refugees travelled overland through the rugged terrain of Central Asia, passing through Iran and present-day Pakistan, before arriving in India. Others reached the Iranian port of Ahvaz and were transported by sea to Bombay. According to contemporary press reports, including an article in The New York Times, the Bandra barracks housed as many as 600 children, aged between two and seventeen. A temporary school was set up within the camp premises where instruction was given in English and Hindi, ensuring a measure of continuity in education for these war-affected youth.

While most of the Polish children were later relocated—either repatriated to Europe or resettled in other countries—their time in India left a deep impression. One of the most enduring memories for these refugees was the benevolence of Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijay Singh of Nawanagar, who provided shelter to many of them for a prolonged period. In later years, a school and a street in Poland were named in his honour as a lasting gesture of gratitude for the hospitality extended to them in India during their time of need.

Post-Independence Era

Following India’s independence in 1947, administrative reorganisation brought significant changes to the political geography of the region. The former Bombay Presidency was restructured into Bombay State, which initially encompassed parts of present-day Maharashtra, Gujarat, and other adjoining territories. A proposal in 1956 to retain Bombay as the joint capital of a bilingual state comprising both Marathi- and Gujarati-speaking regions was ultimately set aside. In 1960, Bombay State was formally dissolved, giving rise to the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat, with Mumbai (then Bombay) becoming the capital of Maharashtra.

Territorial boundaries of the Mumbai Suburban region also shifted during this period. In 1945, 33 villages from the suburban area were transferred to Thane district as part of a broader reallocation. However, in 1946, 14 of these villages were returned to Mumbai Suburban to support the establishment of the Aarey Milk Colony, which was envisioned as a model dairy settlement to supply the growing metropolis.

In 1990, the region was formally designated as a separate revenue district under the name Bombay Suburban, distinct from Mumbai City district. In 1996, a government resolution restored the city’s indigenous identity, and the district was renamed Mumbai Suburban.

Sources

2023.The Rock Chronicles. Open Magazine. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://openthemagazine.com/author/madhavank…

Aarefa Johari. 2012Outcast in Stone. Hindustan Times. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai/outcas…

Akshay Chavan. 2018. Mumbai’s Hidden History. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Anurag. Bhandup Koliwada. Jio Institute Digital Library. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://exhibits.jioinstitute.edu.in/spotlig…

Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). List of Protected Monuments in Mumbai Circle, District-wise. ASI Mumbai Circle.https://web.archive.org/web/20130606093840/h…

Archaeology Magazine Archive. The Slum and the Sacred Cave. May 2007. Accessed on 25 March 2025..https://archive.archaeology.org/0705/abstrac…

Ashutosh Bijoor. 2013. Mandapeshwar Caves, Borivali: Legacy of a Tumultuous Past. Bijoor. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://bijoor.me/2013/09/08/mandapeshwar-ca…

B. Arunachalam, et al. 1986-87. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Greater Bombay District. Vol. I, II, III. Gazetteers Department, Govt of Maharashtra. Mumbai.

Department of Ancient Indian Culture, Sathaye College. Documentation of Caves in MMR. MMRHCS. Accessed March 25, 2025.http://www.mmrhcs.org.in/images/documents/pr…

Heritage Chronicles. 2010. Caves, Temples, Churches and Remnants of the past - Heritage walk in suburb named after sweet berries - Borivali. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://heritagechronicles.blogspot.com/2019…

Karel Staněk, Michal Wanner. 2016. Count Ericeira’s Letter of 1741: A Recently Discovered Document on the History of Portuguese India in the Moravian Regional Archives in Brno. E-Journal of Portuguese History.https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Portuguese…

Khaki Lab Mumbai. 2023. Gadhegals Of Maharashtra By Harshada Wirkud. YouTube. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7bLQ2NeXEg

Louiza Rodrigues. 2010-11. Building railways in Bombay: Land Use Policy of the British in Bombay and Salsette: 1845-1855.Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 71.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147513

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1882 (reprinted in 2000). Thana District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Manish Rai. 2018-19. Brick Stupas: Through Archaeological Vista of the Central India. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 79.https://www.jstor.org/stable/26906316

Mariam Dossal. 1999. Conflicting Interest and Harmonious Planning: Bombay, C. 1898-1928.Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 60.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44144144

Mitali Parekh. 2022. Bombay Before Mumbai. Mid–Day.https://www.mid-day.com/sunday-mid-day/artic…

Mrityunjay Bose. 2022. Mandapeshwar: Equally Important for Buddhists, Hindus, and Christians. Deccan Herald. Accessed on 25 March 2025.https://www.deccanherald.com/india/mandapesh…

N. Benjamin. 2003. Settlement of Salsette Island - The First Phase of Settlement. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 64.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145516

Natasha Sarkar. 2002. Cross-Currents During the Quit India Movement in Bombay. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 63.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44144144?seq=8

Owen Kail. 1984. Elephanta: The Island of Mystery. Taraporevala. Page 21.https://books.google.com/books?id=ylweAAAAMA…

Patel, R. The Slum and the Sacred Cave. Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University. 2007. Accessed on 25 March 2025..https://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/edu/eesj/gradp…

Paulo Varela Gomes. Convent and Church of our Lady of Pity.https://hpip.org/en/Heritage/Details/1074

Pranjali Mathure. 2023. Affluence, Aspiration and Art Deco in Salsette: The Story of Bombay’s Once Northern Neighbour. Art Deco, Mumbai.https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/afflu…

R.D. D'Silva. 1971. Early Phase of Christianity in Bassein. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 33.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145351

S. M. Edwardes, et al. 1909. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Bombay City and Island. Vol. I, II, III. Bombay.

Sifra Lentin. 2021. Bombay’s East Indian community. Gateway House.https://www.gatewayhouse.in/bombays-east-ind…

Theory9. History of Mount Mary Church, Bandra. Theory9. Accessed March 25, 2025.https://www.theory9.in/blog/history-of-mount…

V. G. Dighe. 1967. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: History, Vol III. Chapter 3.Directorate of Government Print, Stationery and Publications, Maharashtra State, Mumbai.

Websites Referred:Wikipedia, Mumbai Suburban, District Website. Archdiocese of Bombay: Official website.

Yesha Kotak. 2018. Tools near Mumbai beach trace human settlements to Middle Stone Age. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/t…

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.