Contents

- Banganga Tank

- Haji Ali Dargah

- St. Thomas Cathedral

- Maneckji Seth Agyari

- Siddhivinayak Mandir

- Mahalakshmi Mandir

- The Asiatic Society, State Central Library

- Moghul Masjid

- Esplanade Mansion

- Flora Fountain

- Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue

- Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus

- Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) Building

- General Post Office Building

- New India Assurance Building

- EROS Cinemas, Cambata Building

- Residential Architecture

- Residences from the 18th Century in Worli Koliwada

- Residences from the 19th Century in Khotachiwadi

- A Residential-cum-Commercial Building from the 1910s in Girgaon

- A Residential Building from the early 20th Century on Grant Road

- Residences from the 1920s in Worli, Naigaon, and NM Joshi Marg

- A Residential Hostel from the 1960s in Churchgate

- Sources

MUMBAI

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Mumbai’s architecture reflects a city shaped by centuries of migration, trade, empire, and religion, layered with experimentation, cosmopolitanism, and profound contrasts. Its built heritage spans from early Hindu religious sites, like the 12th-century Banganga Tank and Walkeshwar Mandir complex, to colonial-era churches, dargahs, synagogues, and the Art Deco commercial buildings of the 20th century. Early structures such as Banganga show how local religious and community life shaped Mumbai’s physical and social fabric long before colonial rule.

The British period introduced Victorian Gothic and Indo-Saracenic styles for public institutions, blending European forms with Indian materials and craftsmanship. Yet, as Preeti Chopra’s A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay (2011) argues, the colonial city was not solely a product of European design. Indian philanthropists and engineers played a crucial role in shaping Bombay’s urban landscape, funding civic buildings and contributing to their construction. Later, the rise of Art Deco architecture in the 1930s, concentrated in areas like Marine Drive, reflected new ideas of modernity, nationalism, and urban growth. This architectural turn showcased Mumbai’s openness to global influences, its cosmopolitan outlook, and its embrace of avant-garde experimentation in design and aesthetics. Over time, Mumbai’s built environment became a canvas for both collective aspirations and individual patronage, a space where diverse communities coexisted and negotiated their identities.

Kidambi (2013) describes Mumbai as “a city of staggering contrasts,” reflected not only in its social landscape but also in its architecture. Across the city, dense clusters of modest, informal settlements stand alongside high-rise towers, luxury residences, and global corporate headquarters. Economic liberalization and globalization have intensified this architectural juxtaposition, introducing gleaming glass-and-steel structures into a cityscape already shaped by colonial-era buildings, Art Deco landmarks, and vernacular forms. Mumbai’s urban fabric embodies both continuity and change, where modernity coexists with longstanding local traditions and identities, creating a dynamic, multilayered architectural environment.

Each architectural layer—whether religious, colonial, or modern—marks shifts in power, community identity, and economic ambition. Taken together, Mumbai’s streets and skylines offer a visible record of a city negotiating between inclusion and exclusion, tradition and experimentation, local identity and global belonging.

Banganga Tank

Banganga Tank, part of the Walkeshwar Temple complex in South Mumbai, is a historic step-well believed to date back to 1127 CE during the reign of the Silhara dynasty. Stepwells, also known as baravs, were more than just water reservoirs—they were architectural marvels that combined utility, spirituality, and artistry, shaping subterranean architecture across western India from the 7th to the 19th century. Believed to be one of Mumbai’s oldest structures, the Banganga tank is linked to the Ramayan, where Bhagwan Ram is said to have shot an arrow into the ground to draw fresh water.

![Stone steps surround the rectangular Banganga Tank in south Mumbai.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/stone-steps-surround-the-rectangular-bang_GONDTmu.png)

Set within a quiet precinct, the large rectangular tank is enclosed by steps on all sides, resembling the ghats of Varanasi. Surrounded by around 108 mandirs—many of which are tucked within adjoining homes and lanes—Banganga has served as both a religious and residential hub for centuries. Though the tank has undergone several alterations over 850 years, it continues to function as a sacred water body and a deeply rooted cultural landmark in Mumbai.

Haji Ali Dargah

The Haji Ali Dargah is a notable site in Mumbai and features Indo-Islamic and Mughal architectural styles. Located on an isle off the coast of Worli, it is connected to the mainland by a 700-yard causeway, which submerges during high tide. The dargah is estimated to be around 400 years old, with the present complex being reconstructed between 1960 and 1964 and the causeway built between 1944 and 1952.

The Haji Ali Dargah complex spans 4,500 square meters and stands 85 feet tall. It is constructed from reinforced cement concrete (RCC) reinforced with steel and slabs of white Makrana marble. The structure features white domes and minarets typical of Mughal architecture. The main hall consists of three side halls, with the western side reserved for women. The central hall is adorned with a marble ceiling and decorated with mirror work.

![White Makrana marble, domes, and slender minarets define the Indo-Islamic and Mughal architectural character of Haji Ali Dargah.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/white-makrana-marble-domes-and-slender-mi_wEcKf2C.png)

St. Thomas Cathedral

St. Thomas Cathedral in Fort, Mumbai, is a prominent example of Neo-Classical and Neo-Gothic architecture. Located in the Kala Ghoda precinct, it was completed in 1718 and opened to the public on Christmas Day. The church was later consecrated in 1837, with Thomas Carr as the first bishop. A clock and tower were added in 1838, and the bell tower was completed the following year.

![Arched windows and a white façade reflect the Neo-Classical and Neo-Gothic blend of St. Thomas Cathedral in Fort, Mumbai.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/arched-windows-and-a-white-facade-reflect_3s2LHlt.png)

St. Thomas Cathedral features a white façade with arched windows, reminiscent of similar structures in Ireland. The interior includes stained glass windows, brass memorials, and antique furnishings that reflect the Anglican traditions of colonial India. The original roof was replaced with a flat RCC slab in 1920 but deteriorated over time. In 1990, restoration efforts replaced it with a pitched roof similar to the original 1865 design.

The cathedral tower serves as both a clock tower and a belfry. It includes moldings, arches, spires, and a rose window at the first-floor level. Though the bells have not functioned since 1798, they remain a part of the building’s historic fabric. The apse is supported by seven flying buttresses, distributing structural forces while allowing for tall stained-glass clerestory windows in the Gothic tradition.

The nave features a vaulted ceiling that leads to the altar, separated by a small chancel that houses the choir and organ. The altar is adorned with stained-glass lancet windows depicting religious scenes, including Christ in Glory, archangels, Mother Mary, and St. Thomas. The clerestory windows above are paired with semi-circular stained-glass windows below, creating a vibrant light effect.

The chancel’s ribbed vault roof, another hallmark of Gothic architecture, includes stone ribs forming a floral pattern. A central light fixture adds illumination to the chancel area. Additional architectural features include Venetian louvered windows in the aisles, designed to suit Mumbai’s humid climate by allowing ventilation while providing shade.

Maneckji Seth Agyari

Maneckji Seth Agyari, also known as Maneckji Seth Fire Temple, is one of Mumbai’s oldest Zoroastrian fire temples. The architecture features a blend of Greek Revival and Persian elements. Founded in 1733 by philanthropist Seth Maneckji Limji Hataria, the Agiary is located in Fort, Mumbai. It holds significant cultural and religious importance for the Zoroastrian community in the city.

The entrance is adorned with Persian-style columns, featuring ram capitals, and Grecian wreaths, resembling a Greek temple. A unique feature of the temple is the bas relief of the Sun on the pediment of the gable. The Atar (holy fire), a prominent symbol in Zoroastrianism, is depicted on the top and sides of the gable, while Corinthian columns further enhance the grandeur of the structure.

![Persian-style columns with ram capitals and Grecian wreaths frame the entrance of Maneckji Seth Agyari, blending Greek Revival and Persian architectural styles.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/persian-style-columns-with-ram-capitals-a_YWam333.png)

A notable feature of the temple is the presence of a five-legged Lamassu, said to represent the five senses, wisdom, courage, and strength. This figure, with the head of a wise man and the body of a bull or lion, is a common motif in Zoroastrian architecture, reflecting the temple’s deep religious symbolism.

Siddhivinayak Mandir

Siddhivinayak Mandir in Prabhadevi is built in a Hindu temple architectural style. The temple was originally constructed in 1801 by Lakshman Vithu and Deubai Patil and later renovated and expanded in 1990 by architect Sharad Athale.

The Siddhivinayak Mandir is a six-storeyed multiangular structure built using pink granite and fine marble. The renovation of the Mandir transformed the structure into a palace-like design with three grand entrances and a gold-plated sanctum. A spacious central hall surrounds the sanctum, with raised seating and a large platform for pujas and mahapujas.

![The external structure of the Siddhivinayak Mandir at Prabhadevi, built in a Hindu temple architectural style, is considered an architectural feat.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/the-external-structure-of-the-siddhivinay_ByCEqjJ.png)

The Mandir summit features a total of 47 crowns, including one central 12-foot dome, three 5-foot crowns, and thirty-three 3.5-foot crowns. The central dome, which rises above the structure, is gold-plated, and the smaller crowns surrounding the dome are made of gold and panchadhatu (a traditional alloy of five metals).

The entire architectural renovation was planned with the convenience of visitors in mind. On peak days such as Tuesdays, Sankashti Chaturthi, and Angarki Chaturthi, the Mandir can accommodate large crowds of over two lakh people. The design allows efficient movement and visibility of the murti from multiple levels, reflecting both religious intent and architectural planning.

Mahalakshmi Mandir

Mahalakshmi Mandir follows traditional Hindu temple architecture. It was built in 1831 by Dhakji Dadaji, a Hindu merchant, and is located on Bhulabhai Desai Road. The temple is dedicated to Devi Mahalakshmi and is one of the most visited temples in Mumbai.

Mahalakshmi Mandir is known for its elaborate carvings, tall spires, and a symmetrical layout typical of Hindu temple structures. The Mandir features a 10.6-meter-high wooden dhwaja-stambha covered in silver and a stone-carved deepmala. The garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) houses the murtis of Mahakali, Mahalakshmi, and Mahasaraswati, and is surrounded by intricately carved stone walls and decorative motifs that reflect the artistic style of the 19th century.

![Tall spires and intricate stone carvings define the traditional Hindu temple architecture of Mahalakshmi Mandir.[6]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/tall-spires-and-intricate-stone-carvings-_hQTCIk5.png)

The Asiatic Society, State Central Library

The Asiatic Society and State Central Library is a prominent example of Neo-Classical architecture in Mumbai. Located in Fort, the building was designed by Colonel Thomas Cowper and completed around 1833. It was intended to house a library, museum, and stamp collector's office, making it an important public institution in the city’s early colonial era.

![The Asiatic Society is an example of Neo-Classical architecture and features a Grecian portico.[7]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/the-asiatic-society-is-an-example-of-neo-_RASEh0m.png)

The structure is best known for its Grecian portico (covered porch), accessed by a grand flight of 30 steps. Eight Doric columns support a Greek-style pediment, giving the façade a resemblance to the Parthenon. The whitewashed exterior, symmetrical proportions, and classical elements reflect strong Greek and Roman architectural influences.

Inside, the building features cast iron pillars imported from England and extensive use of Burma teak for flooring and bookshelves. The structure has three skylights, one each in the north and south wings, and one in the main foyer, allowing natural light to filter into the space. The false ceiling in the foyer and the clean geometry of the structure further emphasize its Neo-Classical character.

Moghul Masjid

Moghul Manji—often called the ‘Blue Mosque’—is a striking example of Persian Shia architecture. Built in 1860 by Iranian merchant Haji Mohammed Hussain Shirazi, it is located in Bhendi Bazaar. Its shimmering blue tiles, central pond, and quiet lawns create a sense of serenity in contrast to the surrounding chaos.

The mosque features two slender minarets and no dome, distinguishing it from typical mosque architecture in Mumbai. Persian tiles imported from Iran line the walls, reflecting the influence of Shiraz’s design traditions. Renovated in 1996 by architect Reza Kabul and again in 2017, the mosque saw the addition of handmade Iranian tiles, stained glass windows, and energy-efficient lighting.

![Moghul Manji’s twin minarets and blue-tiled facade reflect the elegance of Persian Shia architectural design.[8]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/moghul-manjis-twin-minarets-and-blue-tile_cA7FfDD.png)

Esplanade Mansion

Esplanade Mansion, formerly Watson’s Hotel, is India’s oldest surviving cast-iron building and is constructed in Victorian-era architecture. It is located in the Kala Ghoda district of South Mumbai. Built in 1869 for English businessman John Watson, the structure was designed by British engineer Rowland M. Ordish and fabricated at the Phoenix Foundry Company in Derby, England. The prefabricated cast-iron components were shipped to Bombay and assembled on-site, making it one of the earliest examples of modular construction in India.

Originally intended as a luxury hotel and commercial space, the building featured five floors with en-suite rooms, 18-foot-high ceilings, and Burma teak floors. A wide teak staircase and an open atrium added to its grandeur. Its exterior was made of exposed yellow bricks, fired using advanced ceramic technology of the time, and framed by a striking cast-iron structure. Expansive balconies and teak-framed doorways further defined its elegance.

![Esplanade Mansion, India’s oldest cast-iron building, showcases Victorian-era architecture.[9]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/esplanade-mansion-indias-oldest-cast-iron_8hAr89W.png)

Flora Fountain

Flora Fountain is a heritage landmark located at the intersection of Dadabhai Naoroji Road, Mahatma Gandhi Road, and Veer Nariman Road in Mumbai’s Fort area. Its design is influenced by Neo-Gothic and Indo-Saracenic architectural styles, reflecting the colonial-era experimentation with European and Indian design traditions. Its detailed carvings, allegorical figures, and use of imported materials speak to the aspirations and aesthetics of 19th-century British Bombay. Installed in 1869, the fountain is a central feature of Mumbai’s urban and architectural history.

Flora Fountain was commissioned by the Agri-Horticultural Society of Western India and constructed by the British colonial government. It was designed by architect Richard Norman Shaw and sculpted by James Forsythe. Originally meant for Victoria Gardens in Byculla, it was instead installed at its current location. The entire fountain was manufactured in England using Portland stone sourced from Dorset, and shipped to India in parts.

The 32-foot-tall fountain is named after Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers and spring. A statue of the goddess stands at the top, while the four corners of the fountain feature seated, life-size sculptures of female figures representing the four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter. These allegorical figures are dressed in Roman stolas and placed on thrones, symbolizing the cyclical abundance of nature.

The fountain’s lower sections include 64 water sprouts and 20 lion heads, with four fish sculptures at Flora’s feet. A basin at the base collects water, which recirculates through an internal plumbing system. These elements align with the fountain’s symbolic theme of abundance and nurturing. Additional sculptures around the base represent India’s plant-based food systems, further reinforcing the motif of natural prosperity.

![Flora Fountain, a heritage landmark in Mumbai’s Fort area, blends Neo-Gothic and Indo-Saracenic styles.[10]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/flora-fountain-a-heritage-landmark-in-mum_sclXdgs.png)

Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue

Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue is a blend of traditional Jewish and Gothic-Victorian architectural styles. It was built in 1884 by Jacob Sassoon for the Baghdadi and Bene Israeli Jewish communities living in Bombay. Located in Kala Ghoda, the synagogue stands out due to its distinct blue-and-white façade and has become a notable heritage landmark in the city.

Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue is known for its vibrant colour, European-style features, and cultural significance. The exterior includes Corinthian columns, a triangular gable roof, arched windows, and cast-iron detailing. The synagogue’s interiors feature stained glass windows, Minton tiles, chandeliers, and a large ark that houses the Torah scrolls. Religious motifs and symbols decorate the space. The restored colour scheme of pale green and cream reflects the synagogue’s original look from the late 19th century.

![Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue features a blend of traditional Jewish and Gothic-Victorian architectural styles and has a striking blue-and-white facade.[11]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/knesset-eliyahoo-synagogue-features-a-ble_9BRu5oQ.png)

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, formerly known as Victoria Terminus, is a notable example of Victorian Gothic Revival architecture blended with Indian traditional elements. Located in South Mumbai and designed by British architect F. W. Stevens, the structure was built between 1878 and 1888 over an area of 2.85 hectares. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004 for its architectural and cultural significance.

![Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus blends Victorian Gothic Revival and Indian traditional architecture.[12]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/chhatrapati-shivaji-maharaj-terminus-blen_QFiZRd3.png)

The structure blends Victorian Italianate Gothic Revival architecture—such as pointed arches, flying buttresses, and ribbed vaults—with Indian palace-like features, including an eccentric ground plan, a massive octagonal stone dome, ornate turrets, and intricately carved spires. Indian craftsmen collaborated closely with Stevens to incorporate indigenous motifs, including peacocks, lions, tigers, and vines, along with floral patterns and symbolic medallions.

The building’s elaborate detailing reflects a seamless blend of Victorian Gothic and Indian architectural traditions. Decorative gargoyles project from the cornices, serving both functional and ornamental roles. The façade features richly carved tympana above arched openings, along with medallions bearing relief busts of British administrators and Indian railway personnel. Sculptural embellishments across the elevations include gargoyles, allegorical grotesques carrying standards and battle-axes, and figures of relief busts representing the different castes and communities of India. The entrance is marked by two prominent columns crowned with a lion and a tiger, symbolizing the British Empire and Indian identity, respectively. Further embellishments such as lotuses, banana leaves, vines, and other native flora contribute to the distinctly Indian visual elements of the structure.

The rose windows feature intricate stone tracery and stained glass panels depicting religious and mythological scenes. These stained glass elements extend across doors and windows framed in Burma teak and bordered by original wrought iron grills. The dome drum features steel-framed stained-glass windows that allow natural light to filter into the interiors, illuminating painted coats of arms, vaulted ceilings, and decorative panels. Staircases are adorned with cast iron railings and ornamental newels, reflecting the period’s attention to aesthetic detail. Structural materials include locally quarried yellow Malad stone, polished granite, Italian marble, and white limestone used in cornices and moldings for contrast and articulation.

With its monumental scale, hybrid aesthetic, and detailed craftsmanship, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus is not only a functional railway station but also a symbolic assertion of Bombay’s colonial-era importance as a commercial and administrative hub.

Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) Building

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) Building is an example of Victorian Gothic architecture, designed by Frederick W. Stevens. Completed in 1893, it is located on Mahapalika Marg, near Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus. The building was commissioned by the British government to house the Municipal Corporation of Mumbai.

The BMC building features pointed arches, turrets, domes, and intricate carvings, blending Western Gothic elements with Eastern motifs. A prominent feature is the flower-shaped 'oeil-de-boeuf' (ox-eye window), which allows natural light to enter the building during the day. On the north face, a large window made of artistically designed glass is bordered by throne-style carved stone corners.

![Victorian Gothic BMC Building with pointed arches, turrets, domes, and carvings blending Western and Indian motifs.[13]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/victorian-gothic-bmc-building-with-pointe_weYNUPc.png)

The building also includes allegorical figures, such as a winged angel holding a miniature ship, symbolizing Mumbai’s maritime trade. This figure is accompanied by the motto urbs primus in Indis ("the primary urban city of India"), which became the slogan of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation.

The Indo-Saracenic style is evident in the onion-shaped domes with a finial, inspired by Mughal and Deccan Sultanate architecture. The structure is constructed using locally sourced basalt stone, with detailed sandstone carvings. The interior of the BMC building is equally intricate, with brackets inspired by Hindu temple architecture.

![Indo-Saracenic domes and allegorical figures, like a winged angel with a ship, reflect Mughal, Deccan, and maritime influences.[14]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/indo-saracenic-domes-and-allegorical-figu_TxNl6Qx.png)

Gargoyles, chimeras, and griffons are positioned atop turrets, and the building features extensive stained-glass windows throughout, adding to its architectural splendor. The BMC building stands as a symbol of Mumbai’s colonial architectural legacy.

General Post Office Building

The General Post Office Building, located near Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, combines Islamic, Mughal, and traditional Indian architectural elements. It was designed by Scottish architect John Begg and completed in 1913. Built as the postal headquarters during the British era, it is a landmark of colonial Bombay’s public infrastructure.

The building is constructed using black Kurla basalt stone and dressed in Malad yellow and white Dhrangdra stones. The structure is known for its massive dome, one of the largest in Mumbai, which is inspired by the Gol Gumbaz of Bijapur. The building features turrets and minarets inspired by Mughal architecture. The building has a steel-framed structure spread across 1,20,000 square ft. and is currently undergoing restoration to preserve its historic value.

![General Post Office building in Mumbai combines Islamic, Mughal, and traditional Indian architectural elements in its design.[15]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/general-post-office-building-in-mumbai-co_JElTr8v.png)

New India Assurance Building

By the 1930s, Mumbai witnessed a significant architectural shift with the emergence of Art Deco—a style that moved away from colonial ornamentation toward a streamlined, modern aesthetic. This transition reflected the city’s growing cosmopolitanism and the aspirations of a new Indian middle class. Reinforced cement concrete (RCC), a new construction material, allowed faster, more affordable construction and encouraged bold experimentation. Art Deco in Bombay was not just a visual language; it marked an ideological shift. From cinemas and apartments to commercial buildings, the style adapted international influences while incorporating Indian motifs, laying the groundwork for a distinctly new Indian identity in the built environment. The choice of Art Deco—then known as style moderne—was a deliberate one, seen as “a clear rejection of classical colonial architecture and all its baggage” as suggested by Ruchita Madhok (2022).

The New India Assurance Building, located in Fort and completed in 1936, is a prominent example of Bombay’s early Art Deco architecture. Commissioned by the New India Assurance Company—founded in 1919 by Sir Dorabji Tata—it served as the company’s headquarters during the height of the Swadeshi Movement. Situated at 87 Esplanade Road (now Mahatma Gandhi Road), the building signified a shift from colonial architectural styles to a new Indian identity. The name “New India” itself reflected a sovereign, self-governing vision for the people of the subcontinent.

Constructed using reinforced cement concrete (RCC), the building was designed for speed, climate responsiveness, and durability. Its east and west facing facades feature projecting surfaces for sun shading, while transom and mullion windows allow natural ventilation. The structure’s streamlined vertical ribs and geometric composition reflect core Art Deco ideals of symmetry, technology, and modernism.

![The New India Assurance Building is an early example of Bombay Art Deco, featuring vertical ribs and geometric forms.[16]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/the-new-india-assurance-building-is-an-ea_A8QbtSY.png)

Sculptural reliefs by Marathi artist N. G. Pansare flank the main entrance, depicting industrial and agrarian scenes—workers spinning yarn, carrying grain, and transporting goods by sea. Classical sentinels gaze down from above, merging Indian themes with Deco’s visual vocabulary.

These design elements, along with nearby buildings adorned with elephants and Lakshmi, demonstrate how Bombay’s Art Deco adapted international modernism to local cultural narratives. Together with other Deco-era office buildings such as the Laxmi Insurance and Western India buildings, the New India Assurance headquarters made a confident statement for a swadeshi corporate brand. Far from today’s generic glass and steel offices, these heritage buildings remain visible memorials to the ideals of the independence movement—values of self-reliance, service, and a confident national identity.

![A sculptural relief on the New India Assurance Building shows a worker spinning yarn—an Art Deco representation of Bombay’s early industrial identity.[17]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/a-sculptural-relief-on-the-new-india-assu_IXf54KG.png)

EROS Cinemas, Cambata Building

The Cambata Building, commonly known as Eros Cinemas, is an example of the Art Deco architectural style. Located opposite Churchgate railway station, it was designed by architect Shorabji Bhedwar and built in 1938.

The building features a ziggurat-shaped structure, curved edges, and a facade of pale cream and red Agra sandstone with elongated windows. The two curved wings meet at a central vertical block that rises in a stepped form. Vertical frames across the facade create a sense of motion, while horizontal red bands with relief work add visual contrast. Inside, grand marble staircases and chromium handrails enhance the building’s Art Deco appeal.

![Vertical frames and horizontal red stone bands on the Cambata Building create a dynamic interplay—typical of Bombay’s Art Deco style.[18]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/vertical-frames-and-horizontal-red-stone-_2KsMPPU.png)

Residential Architecture

In Mumbai, the architectural landscape is marked by a stark contrast between old and new—low-rise, dense settlements like chawls and Koliwadas coexist with towering skyscrapers that dominate the skyline. Older structures, such as those in Worli Koliwada or the BDD chawls, often built generations ago, continue to function as lived spaces. In contrast, limited land and a rising population have led to vertical expansion across the city, making skyscrapers a defining feature of new construction. In neighbourhoods like Girgaon and Worli, these older residences form tight-knit communities and coexist beside high-rise buildings that characterise Mumbai’s contemporary development. The result is a built environment that is not uniform but one where architectural disparity captures the city’s ongoing transformation.

Residences from the 18th Century in Worli Koliwada

Before the late 18th century, Mumbai was not a single landmass but a group of seven distinct islands, Mahim, Worli, Parel, Mazagaon, Bombay, Colaba, and Little Colaba. These islands were later merged through land reclamation to form the city as it exists today. The Koli people of Worli inhabited the area when it was still an archipelago. “Koliwada,” meaning fishing village, refers to a triangular stretch of land in Worli, surrounded on three sides by the sea, shaping its cultural and economic practices. The village emerged as a fishermen’s settlement and continues to function as one, with generations carrying forward their traditional way of life. Long before Mumbai became a metropolitan hub, the Worli Koliwada embodied the lived experiences and cultural heritage of its people.

The built environment of Worli Koliwada reflects the Koli community’s evolving cultural and architectural practices. This dense, unplanned settlement developed centuries ago to house the fishing community. Over time, the houses have adapted, incorporating architectural changes that blend old and new elements. The lanes feature structures from different time periods, resulting in a varied and organic architectural landscape rather than a uniform style. Today, Worli Koliwada remains a vibrant urban village with narrow winding lanes, and colorful homes.

The village layout has remained mostly unchanged, with a central spine running through it and leading to the coastline. This coastal stretch serves as a workspace for boat repairs, fish drying, and net arrangements, reinforcing the settlement’s deep connection to the sea. At the village center stands a shrine surrounded by houses.

The alleys of Worli Koliwada are remarkably narrow; the village is inaccessible to cars. As one moves deeper into the settlement, the lanes become even tighter, weaving through a dense cluster of homes and revealing the organic, unplanned nature of the village’s growth.

The settlement follows a high-density, low-rise pattern. The older houses in Worli Koliwada are typically single-storey structures with sloping roofs, small rooms, and verandahs. In contrast, newer houses rise taller with flat roofs. Some of these upper floors, added over time, are rented out to migrants at low rates. Access to these floors is provided by external ladders, as staircases remain absent.

Residences typically feature a small verandah in the front, raised on a low stone plinth. The ground floor is often clad with tiles, and narrow pathways paved with stone tiles wind between the houses.

Interestingly, a variety of materials mark the evolving nature of construction, reflecting incremental changes over time. Walls are built with cement panel brickwork and reinforced concrete cement (RCC), while roofs are made of metal sheets or clay tiles, often extending over the street.

Doors and windows incorporate mixed materials, primarily aluminum and wood. Each renovation introduces new materials, creating a layered architectural history.

The area has several public toilets; however, these are poorly maintained and are thus rarely used. The more affluent families have incorporated toilets inside their homes.

However, Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) schemes and rapid urban redevelopment pose serious threats to the Koliwada. Encroachment on fishing grounds, shrinking village spaces, and restricted coastal access undermine the environmental and economic foundations that have sustained the Koli community for centuries, as high-rises and infrastructure projects replace traditional homes and livelihoods.

Residences from the 19th Century in Khotachiwadi

Khotachiwadi, located in Girgaon, is one of Mumbai’s few surviving heritage gaothans (villages or settlements specifically inhabited by the East Indian community). Established in the 19th century, the village was originally part of the outskirts of Bombay and became part of the city only after British expansion reached the area. The land belonged to Waman Hari Khot, who sold parcels to members of the Bombay East Indian community. The community—Catholic and their history tied to the Portuguese—major influences from them can be seen in their culture. Same can be seen in the architecture of the gaothans they live in.

Historically, the area was home to the Koli and Pathare Prabhu communities, and the settlement reflects a layered cultural and architectural heritage shaped by Portuguese, local, and colonial influences. Today, Khotachiwadi stands as a rare example of a cohesive East Indian urban village within the dense fabric of South Mumbai. Colour plays a defining role in the visual identity of the settlement — deep blues, reds, greens, and yellows respond to the lush vegetation and contribute to a unified yet vibrant streetscape.

![A narrow lane in Khotachiwadi with houses painted in vibrant colors, set amidst greenery.[19]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/a-narrow-lane-in-khotachiwadi-with-houses_EmRZRdK.png)

Khotachiwadi emerged as an unplanned settlement, with narrow, winding lanes and irregular plot sizes. Stone-paved pathways run between densely built houses and occasionally open into small courtyards or shrine spaces marked by crosses. The overall street character is quiet and pedestrian-oriented, shaded by large trees that interlace with the built fabric.

Residences here typically follow a high-density, low-rise form with ground-plus-one or ground-plus-two storey layouts. The houses are made primarily of timber, with wide verandahs and projecting balconies that face the street.

![Brown and cream-colored timber house in Khotachiwadi with a wide front verandah and a projecting balcony overlooking the street. A sloping roof extends across the structure, including above the front porch.[20]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/brown-and-cream-colored-timber-house-in-k_tq7SDDh.png)

Doors are often made of carved wood, framed by simple yet distinct pilasters or lintels. Roofs are pitched and clad with Mangalore tiles in mosaic shades of red and orange, supported by timber trusses and deep overhangs that protect façades from rain and sun.

Windows in Khotachiwadi typically feature timber shutters with latticework or glass panes, allowing for light, ventilation, and privacy. They are often recessed into thick walls, framed in wood, and decorated with intricate detailing.

![Recessed box window in Khotachiwadi with an arched top, wooden framework, and beautifully carved latticework grills.[21]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/recessed-box-window-in-khotachiwadi-with-_VVxVVPD.png)

Staircases in Khotachiwadi are mostly external and made of wood, with latticed or carved railings. These timber staircases lead directly to upper floors, often connecting with open verandahs or balconies.

![Vibrant green external staircase in Khotachiwadi with timber railings, connecting directly to the upper floor verandah.[22]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/vibrant-green-external-staircase-in-khota_WFLARsv.png)

Decorative fascia boards under the eaves are a consistent feature across homes, with designs varying from floral motifs to geometric cutouts. The base of each house often includes a low stone plinth, sometimes tiled, which raises the structure slightly above street level. Together, these elements create a vernacular architectural language that blends functionality with cultural memory. Today, it has been noted that only 27 of the original 65 houses remain. While some homes show signs of piecemeal repair using cement or metal sheets, most continue to reflect their historic character.

A Residential-cum-Commercial Building from the 1910s in Girgaon

Girgaon, one of the early settlements in Mumbai, is situated at the foot of the Malabar Hills. The area developed as an early fishing village populated by the Kolis and the Pathare Prabhu community—the original settler communities of Bombay. The name ‘Girgaon’ derives from the Sanskrit words giri (hill) and grama (village), referencing its location near the hills and its early settlement patterns. By the mid-19th century, the area saw an influx of migrants, transforming it into a dense residential quarter. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Girgaon continued to grow as new communities arrived, including Gujaratis, Maharashtrians, Konkani speakers, Parsis, and East Indians and since then has become a microcosm of cultural identities. By the early 20th century, Girgaon had become an established urban district, characterized by a mix of traditional wadas, chawls, and newer residential buildings.

The Servants of India Society’s Building in Girgaon, an early 20th century structure on Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Road, reflects that transition. The Servants of India Society was founded by Gopal Krishna Gokhale (in addition to GK Devadhar, A.V. Patwardhan, and N.A. Dravid) in Pune in 1905. The society was envisioned as a training ground for individuals dedicated to the country's cause, focusing on political education, advocacy, and advancing national interests through constitutional means. Over time, the society expanded by opening branches in other cities. One such branch was this building in Girgaon.

Built in 1911, the building initially functioned as a branch of the society, aimed at carrying out various social welfare activities and as a primary school; the building has since then undergone multiple transformations to adapt to changing urban needs. Currently functioning as a commercial-cum-residential space, its ground floor accommodates shops while the upper floors serve as residences.

Positioned at the intersection of two streets, the building is largely symmetrical and features a reinforced cement concrete (RCC) column framework with brick walls and a plastered finish. The golden embellishments on the façade reflect colonial influences, lending the structure a distinct aesthetic reminiscent of Mumbai’s early 20th-century urban fabric.

The building features balconies with precast balustrades on the upper floors and windows with aluminum-framed sliding units with glass panes, likely a later addition.

The doors are double-panelled and made of wood. The windows follow a similar wooden, double-shuttered design, with an opaque glass panel above. Both the doors and windows incorporate louvered openings for ventilation, enhancing airflow within the structure.

The building's staircases are wooden with a metal covering, painted in bold, contrasting colors. The railing features carved white wooden balusters, adding a decorative element to the structure.

The terrace combines china mosaic tiles with exposed cement surfaces. With a relatively low parapet, it offers an unobstructed view of the surrounding buildings. While part of the building has a flat, open roof, the other section features a sloping roof made of clay shingles, reflecting traditional roofing styles.

This structure in Girgaon was renovated in 2019 by the Mumbai Repairs and Reconstruction Board.

A Residential Building from the early 20th Century on Grant Road

Among the notable structures on Grant Road is Pannalal Terrace, a residential society estimated to have been built around 1911.

The society is over a century old, estimated to have been built in 1911. While no formal redevelopment has taken place, interior renovations have been carried out over the years to maintain structural stability and retain the building's heritage character. Brick, cement, wood, and natural stone (Kota stone) make up the composite structure of the buildings. The five-storey building maintains a neutral color palette.

Located adjacent to a busy street, the society is not a gated community and follows a mixed-use pattern. The ground floor is occupied by commercial establishments, while the upper floors are residential.

Within the society, a large open courtyard serves as a common space for events and community activities. Parking is done informally along the curbside, as no designated parking slots or formal provisions exist. Notably, in a city like Mumbai, where both parking and open space are limited, this society offers both.

The main entrance door comprises two layers—an outer safety door with iron grills on the upper half, and an inner wooden door that serves as a visual barrier. Both doors are double-shuttered, made of wood, and painted in blue. The aldrops are made of iron. Above the entrance is a small clerestory window designed to aid ventilation.

The entrances to the apartments have two doors—both double-shuttered and finished in laminate over plywood. The outer doors have grills on the upper half, mainly for ventilation and safety. These doors appear to be refurbished and do not seem to be part of the original construction. In some units, modern plywood doors with a laminated finish have been added as part of minor renovations.

The windows are recessed deep within the thick masonry walls, creating an interior ledge often used for storage. They are double-shuttered, made of wood, painted, and equipped with a tower bolt. Above each main window is a clerestory window designed to allow ventilation, essential to beat Mumbai’s heat. This upper panel is a wooden top-hung frame fitted with an iron grill and a glass pane that enhances natural light within the interiors. A mosquito mesh panel, likely a later addition, has also been installed.

Some residents have renovated the original window by replacing it with an aluminum sliding unit fitted with glass panes. In addition, the clerestory window above has been sealed off and repurposed as an overhead storage cabinet.

A common passage runs along the outer edge of the building, functioning as a shared balcony. These spaces are typically used by residents for utility purposes. Wooden doors with iron grills open into the balcony area, which is enclosed with cast iron parapet grills fitted into a wooden frame.

Similarly, a main lobby passageway runs through the interior of the building, connecting all apartments. Covered with a roof projection, it is protected from rain and weather exposure. The floor is finished with natural stone tiles. The railing comprises vertical metal bars fitted between columns, with an RCC top member. The entrances to the apartments are marked by tiles cladding along the doorway walls.

The staircases are made of wood and painted in vibrant dual colors. The railing is also wooden, featuring carved balusters. Windows placed at each landing allow natural light to filter in through the day and help maintain cross-ventilation across the stairwell.

Common toilets and baths are located near the staircase, accessible to all residents. These spaces have clerestory windows fitted with precast concrete grills for ventilation. The doors are made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) set within aluminum frames.

Residences from the 1920s in Worli, Naigaon, and NM Joshi Marg

The chawl typology is a distinctive form of mass housing largely unique to Mumbai, shaped by the city’s rise as a financial capital and its rapidly growing population in the early 20th century. Designed to accommodate a specific class of people—primarily industrial and service workers—chawls provided affordable, dense living spaces close to workplaces. Each chawl developed its own social character: some housed labourers, others merchants or service staff, fostering close-knit communities across diverse social backgrounds. The Bombay Development Department (BDD) chawls, built in the 1920s, stand as an early example of this typology. Interestingly, they were first used by the British to house prisoners and later freedom fighters before evolving into rental housing for Mumbai’s working class. Over time, they became home to mill workers and migrants from various linguistic communities, cementing their role in the city’s social and architectural fabric. Today, chawls are valued for their communal life and shared histories, even as they face rapid decline under redevelopment pressures.

The chawl typology in Mumbai emerged in the early 1900s as a mass-housing solution for countless families. Each chawl had a distinct social identity—some housed labourers, others the service class or merchants. Most chawls nurtured strong community bonds and brought together people from diverse social groups. Today, these rapidly disappearing structures are the subject of growing historical and architectural interest, celebrated for their close-knit living, open doors, and communal life.

According to an article in the Deccan Herald, as of 2020 more than 16,000 families live in these cramped 160-square-foot homes of the BDD chawls, facing issues like poor ventilation and shared bathrooms and toilets. Although these buildings were known for their structural strength, they have deteriorated over the years. MHADA has been tasked with redeveloping the chawls, relocating current residents of 160-square-foot homes to 500-square-foot apartments while preserving the original structures as historical landmarks.

The composite structure (a technical term used to describe the materials that make up the building) of the chawl comprises of reinforced cement concrete (RCC) column beam structure. Typically, these chawls have three to four storeys. Each unit comprises a small kitchen and a sleeping area, designed to accommodate around three people, with shared toilets.

Over time, as families have prospered, they have begun expanding their homes. This expansion usually involves knocking down a wall near the window to create more space. Initially, only ground-floor residents carried out such extensions; however, residents on upper floors, too, have started doing so. The upper-storey expansions are being done by installing a large steel structure from the ground up to support extended rooms on the higher floors.

The structure features brick-textured embossing with neutral color tones. The terrace parapet consists of precast balusters with a top rail. Drainage pipes are exposed along the façade. Some units have added box windows as extensions.

A common passage connects the individual units. The passage has a cemented floor, with some residents opting to tile the space outside their homes. This shared area serves multiple purposes, often used for drying clothes, placing washing machines, or storing household items like toys.

The doors are individual to each apartment and vary in material and aesthetic—ranging from PVC and FRP to wood. Above many of these entrances, decorative torans made from woven materials are tied, adding a personalised cultural touch.

The windows are box-type, framed in granite with mild steel (MS) grills. In some units, the original windows have been replaced with aluminum sliding windows fitted with glass panes.

The staircase is finished with tiles, while the railing is made of painted MS. Its design is minimal and modern, contrasting with the building’s otherwise traditional elements.

A Residential Hostel from the 1960s in Churchgate

Churchgate, an area in South Mumbai, traces its origins to the colonial era when the city was a fortified settlement. In the name, ‘church’ refers to the 300-year-old St. Thomas’ Cathedral, while ‘gate’ alludes to one of the main entrances to Mumbai which stood near the church. The walls are long gone and Churchgate now stands testament to the city’s evolution. The locale houses colonial-era buildings, Art Deco landmarks, and modern skyscrapers, all coexisting in a seamless flow. In its streets, train stations, and institutions, the essence of Mumbai is palpable—always moving forward, yet deeply rooted in its past.

Among Churchgate’s many notable landmarks is the Jugonnath Sunkersett Hall University Hostel, popularly known as JS Hall. Named after Jugonnat Sunkersett, a renowned Indian philanthropist and educationalist, JS Hall has been a cornerstone of student life in the city. Sunkersett was an active leader in many arenas of life in Mumbai with notable achievements in the advancement of education. He co-founded the Elphinstone Educational Institution, known previously as the School Society and the Native School of Bombay.

JS Hall was inaugurated by Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, the then Prime Minister of India. Designed by widely-acclaimed architect Charles Correa, the hostel reflects both historical significance and architectural ingenuity. Awarded the title of India’s Greatest Architect by the Royal Institute of British Architects, Charles Correa is famous for blending India’s cultural and climatic conditions with modern architecture, leading the way to several successful projects in the country.

![Charles Correa[23]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai/architecture/charles-correa23-e6c349e6.png)

JS Hall is an example of the architect’s unique style. Built in 1958 in Churchgate, and renovated in 2022, the hostel is a five-storey structure that balances functionality with a sense of community. The building is situated on Pandit Shobhnath Mishra Marg, the road connecting Churchgate Railway Station to Marine Drive. Set slightly back from the compound wall, the hostel is positioned along the main road. The paved road leading to the building has cars parked on either side.

The building has a modernistic appearance, with balconies arranged in a visually harmonious pattern. It has a neutral base color, with balconies highlighted in a bright brick-red color.

The hostel features a wide concrete entrance marked in blue at the center of the building. The stairs leading to the entrance have a natural stone finish.

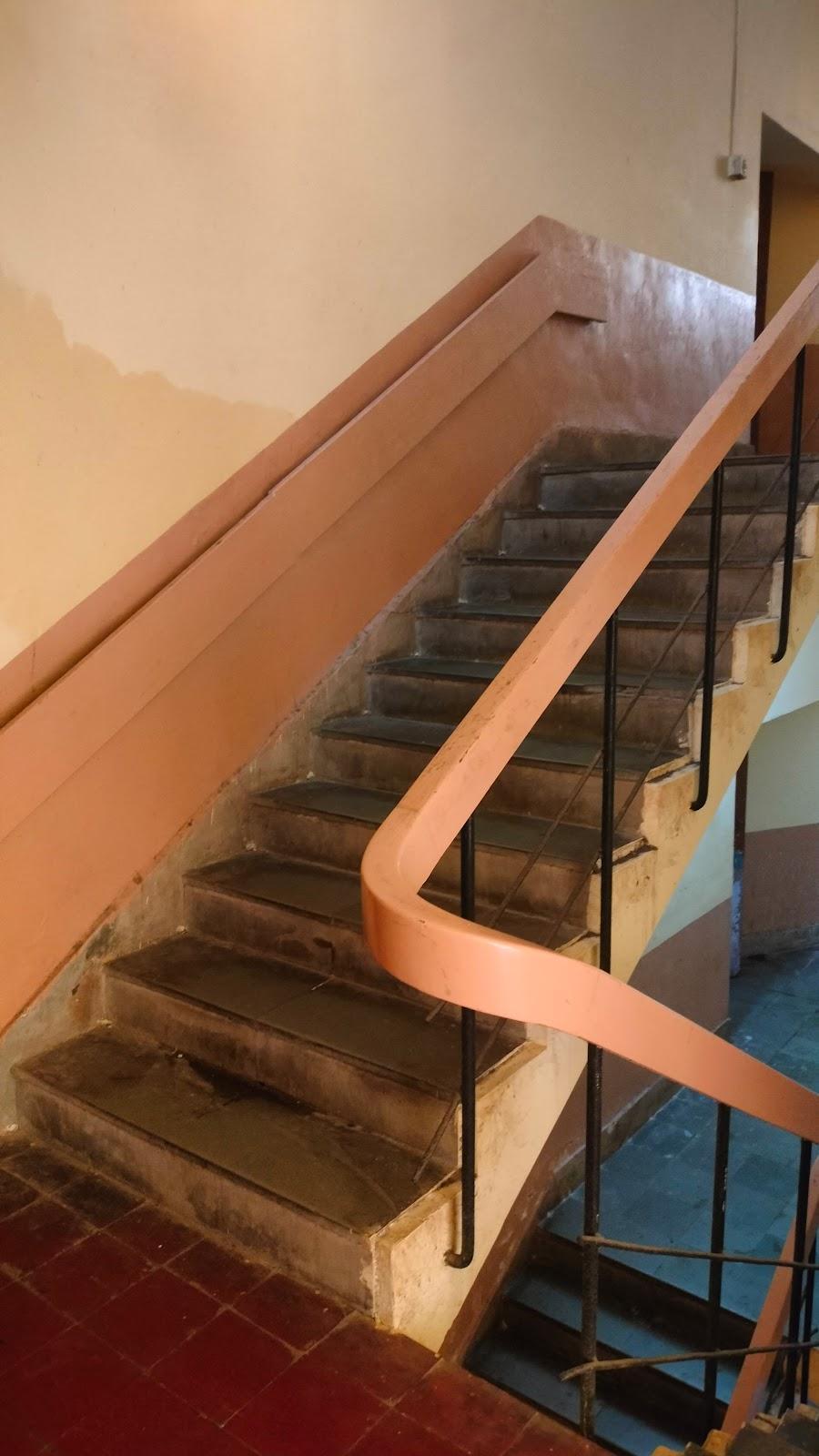

The staircase inside the building is made of reinforced cement concrete (RCC), finished with a polished stone surface. The railings are metal, with supports fixed directly to the stairs and finished with a continuous mild steel band. Adjacent to the wall, the railing is fixed along its surface.

Each room has a wooden door with a simple, panelled design on the upper half, finished with polish. The upper clerestory windows above the door and on other walls of the room play an important role in ventilation, allowing cooler air to circulate through the interiors.

The rooms are arranged along an open, balcony-like corridor, connected by a shared passage with dark brick-red tiled floors. Notice the clerestory windows in the passage; these create a funnel effect for air circulation—smaller openings draw in air with greater force, while larger windows allow hot air to escape.

The bottom storey, used for official purposes, has large windows with mild decorative grills and glass panels.

On the upper storeys, each room has a narrow, stand-in balcony. The parapet is a modern design element, with RCC walls topped by a sleek metal rail.

Sources

Amos Rapoport. 1969. House, Form, and Culture. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Anahita Ahluwalia. 2024. Moghul Masjid: Mumbai’s Blue Mosque Is A Hidden Sanctuary Of Persian Art. Homegrown.https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-explore/mo…

Anshika Jain. 2019. Flora Fountain: Looking To The Future. Peepul Tree Stories.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Arman Khan. 2021. The history and stories from Mumbai's most beautiful neighbourhood, Khotachiwadi. Architectural Digest.https://www.architecturaldigest.in/story/the…

Arushi Jaswal. Restoration of St. Thomas Cathedral by Brinda Somaya: The entwined history of Mumbai. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-st…

DAG Museums. 2025. BMC (BrihanMumbai Mahanagarpalika). Instagram.https://www.instagram.com/p/DHVgr5JIuEZ/

Devashrita Gujral. 2024. The Capital BKC: A Comprehensive Guide to Mumbai's Premier Business Hub. Jugyah.https://jugyah.com/blogs/must-knows/the-capi…

GD House. 2018. Grant Road, Mumbai. Medium.https://medium.com/@gdhouse/grant-road-mumba…

Haji Ali Dargah. Restoration of Haji Ali Dargah. Haji Ali Dargah.https://www.hajialidargah.in/hajiali_restore…

HT Correspondent. Insider’s guide to... Asiatic Society Library. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/art-and-cultu…

Incredible India. Mahalakshmi Temple: A spiritual oasis in Mumbai's bustling heart. Incredible India.https://www.incredibleindia.gov.in/en/mahara…

INTACH. Conservation of General Post Office (GPO) Building – Mumbai, Department of Posts, Ministry of Communication & Technology. INTACH Architectural Heritage.http://architecturalheritage.intach.org/?p=2…

Isha Chaudhary. 2024. Khotachiwadi: A Portuguese Village in the Heart of Mumbai. The Decor Journal.https://www.thedecorjournalindia.com/khotach…

Jio Institute. Flora Fountain. Jio Institute.https://exhibits.jioinstitute.edu.in/spotlig…

Jio Institute. Victorian Gothic at Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). Jio Institute.https://exhibits.jioinstitute.edu.in/spotlig…

Megan Jett. 2011. In Progress: The Capital / James Law Cybertecture International. ArchDaily.https://www.archdaily.com/152648/in-progress…

Mrityunjay Bose. 2020. Maharashtra: Once jail, Mumbai’s BDD chawl will now house a museum. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com/india/maharasht…

Parsi Khabar. 2020. Maneckji Seth Agiary: Parsi Imprint on Mumbai. Parsi Khabar.https://parsikhabar.net/bombay/maneckji-seth…

Prasad Bhave. 2015. Girgaum: The forgotten heart of Mumbai. WordPress.https://prasadbhave.wordpress.com/2015/03/16…

Prashant Kidambi. 2013. Mumbai Modern: Colonial Pasts and Postcolonial Predicaments. University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom. DOI: 10.1177/0096144213479326https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/009…

Preeti Chopra. 2011.A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ruchita Madhok. 2022. Swadeshi Sculptures on the New India Assurance Company Building in Fort, Mumbai. Paper Planes.https://www.joinpaperplanes.com/swadeshi-scu…

Sayli Godbole. 2021. What It’s Actually Like To Live In A Mumbai Chawl. Homegrown.https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-explore/wh…

Servants of India Society. Our Work: Branches & Centres. Servants of India Society.https://www.servantsofindia.in/branches-cent…

Shreyan Das & Adil Raseef. 2024. From fishnets to cityscapes: The Koli chronicles of Worli. Centre for Development Policy and Practice.https://www.cdpp.co.in/articles/from-fishnet…

Sigfried Giedion. 1959. Space, Time, & Architecture. 3rd ed. Harvard University Press.

St. Thomas Cathedral Mumbai. History of St. Thomas Cathedral. St. Thomas Cathedral.https://www.stthomascathedralmumbai.com/site…

Sudarshan Uppunda. Architecture of Mumbai :The rich Architectural Heritage of Mumbai. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fre…

Sumeyye Okumus. 2025. 6 Impressive Works of Charles Correa in India. Parametric Architecture.https://parametric-architecture.com/6-impres…

Suryasarathi Bhattacharya. 2021. Esplanade Mansion: As 155-year-old Mumbai landmark faces its end, a look at its past, present and future. Firstpost.https://www.firstpost.com/long-reads/esplana…

The Culture Project. 2019. The land full of Paradoxes :Banganga. Medium.https://medium.com/@thecultureproject/the-la…

Tushi Gogoi. 2024. Discover the Charm of Churchgate: A Comprehensive Guide. Jugyah Blogs.https://jugyah.com/blogs/guides/churchgate-g…

UNESCO World Heritage Convention. n.d. Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus). UNESCO World Heritage Convention.https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/945/

Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar. 2019. Discovering Mumbai’s Art Deco Treasures. The New York Times.https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/travel/mu…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.