Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Walkeshwar and the Tradition of Banganga

- Early Dynasties and the First Mentions of Mumbai

- Cavel and Traces of a 4th-Century Settlement

- The Shilhara Dynasty and Its Four-Century Rule

- The Figure of Bimb and the Rise of Mahim

- Medieval Period

- Gujarat Sultanate

- The Treaty of Bassein/Vasai

- The Portuguese, 1534 CE-1661 CE

- Expansion of Christianity

- The Manor House

- Khotachi Wadi: Mumbai’s Portuguese Architecture Village

- Trade Policy of the Portuguese

- A Glimpse into the Contrast Between the 16th and 17th Century Bombay

- Colonial Period

- Gerald Aungier, The Founder of Bombay

- Bombay Mint, 1670

- The First Anglo-Indian War, 1686 - 1690

- Piracy Disrupts Bombay's Trade

- Governor Charles Boone

- Relation between EIC and Local Powers (1722-1764)

- Yaqub Sidi and the Janjira Siddis

- The Angres

- The Maratha Confederacy

- Making of Bombay in the 18th Century

- Relationship Between The Marathas and The EIC

- Developments in the Later Half of the 18th Century

- St. George Fort

- Mazgaon Dock

- Local Administrative Changes

- The Hornby Vellard and the Making of Mumbai City

- Sion Causeway (1798–1805)

- Colaba Causeway (1835–1838)

- Mahim Causeway (1841–1846)

- Mumbai’s Cotton Boom and the Birth of Indian Capital Markets

- The Rise of Industry and India’s First Stock Market Crash

- The Great Fire of 1803

- Restructuring the Fort Area

- The End of the Maratha Threat

- A Road Through Bhor Ghat: Connecting Bombay and Pune

- The Mumbai Mint

- Educational Advancement

- Flourishing Economy with Local Markets

- The Bombay Dog Riots, 1832

- Asiatic Society of Mumbai Town Hall, 1833

- The Bank of Bombay, 1840

- Parsi-Muslim Riot, 1851

- The Great Indian Peninsula Railway, 1853

- University of Mumbai, 1857

- First War of Independence, 1857

- Reconstruction of the Fort Area

- Progress in Trade

- Bombay Municipal Corporation

- Chattrapati Maharaj Shivaji Terminus

- Bombay Plague, 1896

- Cuff Parade

- The Hindu-Muslim Riot of 1893

- The Swadeshi Movement in Bombay

- The Bombay Congress Session, 1904

- Opening of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel (1903)

- Select Historical Structures

- General Post Office

- Custom House

- Prince of Wales Museum

- Royal Opera House

- Gateway of India

- From Congress Reunification to Tilak’s Home Rule Campaign (1915–1919)

- Gandhi in Bombay and the Rowlatt Satyagraha (1917–1920)

- Non Cooperation Movement, 1920

- Swadeshi Movement and Commercial Mobilisation, 1921

- Businessmen and Nationalism

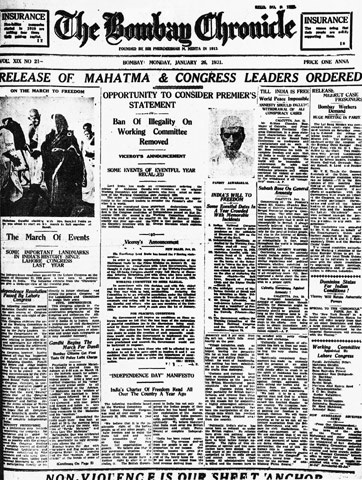

- The Bombay Chronicle, 1920s

- Civil Disobedience, 1930

- Economic Impact

- Religious and Political Tensions

- K.F. Nariman and Congress Politics

- Revival of the Economy and Labour Reforms

- Formation of Greater Bombay

- Quit India Movement, 1942

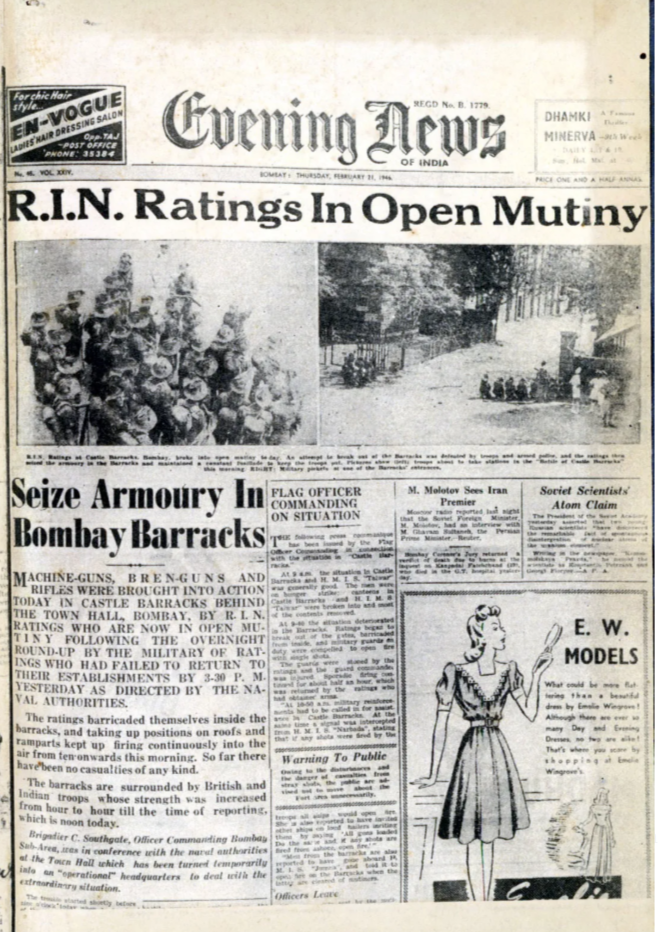

- Royal Indian Navy Mutiny (1946)

- Post Independence

- Samyukta Maharashtra Movement and Hutatma Chowk (1955)

- The Birth of Navi Mumbai

- Dalit Panthers and the Fight Against Caste Oppression

- Great Bombay Textile Strike, 1982

- Bombay Riots, 1992-93

- Bombay Bombings, 1993

- Emergence of Mumbai City

- 2003 Mumbai Blasts

- 2006 Train Bombings

- 2008 Mumbai Attacks

- Sources

MUMBAI

History

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

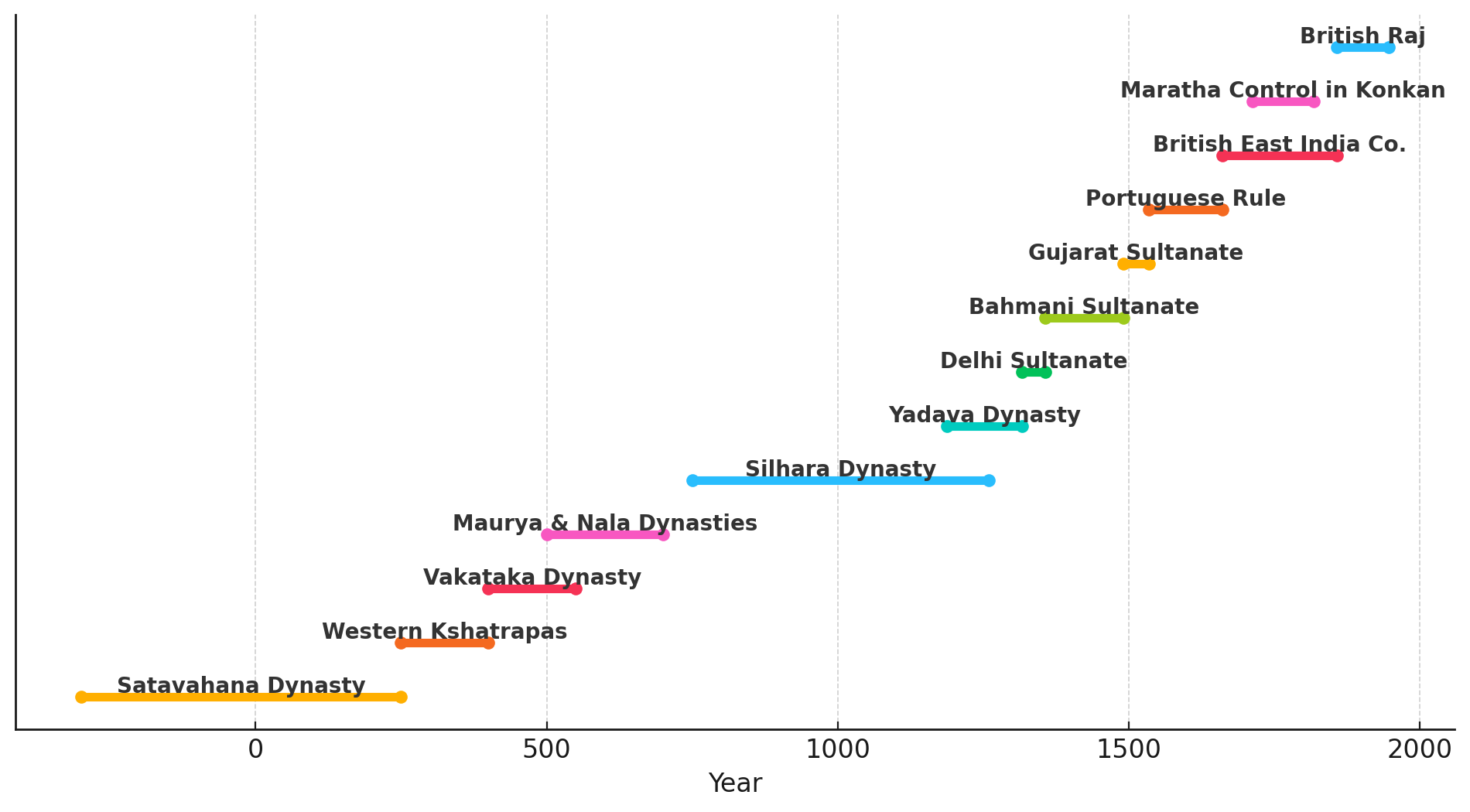

Now recognised as the financial capital of India and the administrative centre of Maharashtra, Mumbai City traces its origins to what was once a scattered group of islands along the Konkan coast. The familiar tale of the seven islands—merged over centuries into a single urban mass—continues to shape public memory. Yet Mumbai’s past is more layered than commonly assumed. The earliest known reference to the region is believed by some scholars to appear in the works of Ptolemy, the 1st-century CE Greek geographer, who used the term Heptanesia, meaning “seven islands.” In the early medieval period, the area came under the rule of the Shilahara dynasty (810–1260 CE), whose control over the region lasted more than four centuries. During the 13th and 14th centuries, Raja Bimba, a lesser-known figure in local tradition, is believed to have established his capital at Mahim.

The area subsequently passed into the hands of the Gujarat Sultanate, and in the 16th century, into the possession of the Portuguese, who left a lasting imprint on the region’s architectural and cultural landscape. In 1661, the islands were transferred to the British Crown as part of a royal dowry on the marriage of Charles II of England to Catherine of Braganza. Soon after, they were leased to the British East India Company, which undertook a series of land reclamation projects that gradually connected the fragmented islands. By the early 19th century, these efforts had created a contiguous landmass—laying the groundwork for the emergence of modern Mumbai as an urban and commercial centre of growing importance.

Etymology

Mumbai City is home to diverse communities and among these the Koli people hold a special place. Believed to be the city’s oldest inhabitants, their presence here stretches back centuries. The very name "Koli" is derived from the Marathi word "Kolah," meaning "fisherman”. This in itself speaks volumes about the community’s deep connection to the coastal city, the sea and their traditional way of life. Due to their significant association with the legacy and history of the region, the district’s name was changed from Bombay to Mumbai in 1996. The word ‘Mumbai’ comes from the name of the Kuldevi (family deity) of the Koli community known as ‘Mumba Devi’.

It should be highlighted that Mumbai was earlier known as Bombay, the name given to the city by the Portuguese. Derived from their term "Bom Bahia" meaning "good bay," it reflects the region's natural harbor that first attracted them.

Ancient Period

Walkeshwar and the Tradition of Banganga

While many associate Mumbai’s origins with the colonial era—especially the Portuguese dowry to the British Crown in the 17th century, as mentioned above, the city’s history stretches much further back in time. One of the most enduring glimpses into its ancient past can be found at Walkeshwar, situated on the slopes of Malabar Hill.

According to long-standing tradition, the origins of the shrine go back to the time of the Ramayan. It is said that Bhagwan Ram, while passing through this region on his journey southward in search of Sita, paused at the spot and was advised to worship Bhagwan Shiva. In response, he fashioned a shiva linga out of sand—hence the name Valuka Ishwar (sand-made Ishwar), which in time evolved into “Walkeshwar.”

At this time, another account describes Bhagwan Ram quelling his thirst by shooting an arrow into the ground, causing a freshwater spring to emerge. This spring continues to feed the adjacent tank, known as Bana Ganga—“Arrow Ganga.” Notably, the tank retains its freshwater character despite its proximity to the sea, and remains in use to this day.

Early Dynasties and the First Mentions of Mumbai

In the centuries that followed, the islands that now form Mumbai fell under the influence of multiple dynasties, though records from this early period remain limited. The region’s proximity to ancient urban centers like Sopara and Kanheri, both active nodes of trade and religion, suggests that the area likely experienced some cultural and economic spillover.

Located just north of the present-day city, Sopara (ancient Shurparaka) was a well-known port in antiquity, frequently mentioned in Buddhist texts and trade records. It served as a key maritime hub, connecting western India to the wider Indian Ocean trading network.

To the northeast, the Kanheri Caves, nestled within what is now the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, offer some of the earliest surviving material evidence of religious and cultural activity in the region. These rock-cut Buddhist caves developed over several centuries through sustained dynastic patronage, especially from the Satavahanas, Traikutakas, and later Shilaharas.

According to the Documentation of Caves in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region report, Kanheri’s history is typically divided into three broad phases:

- Early Phase (2nd century BCE – 4th century CE): Under the Satavahanas, Kanheri began as a modest monastic complex, with monks excavating simple viharas and chaityas. The dynasty was heavily involved in trade, and their influence likely extended into the coastal settlements of the Mumbai islands.

It is from this period that we get what may be the earliest textual reference to Mumbai: the Greek geographer Ptolemy, writing in the 2nd century CE, refers to a region he calls “Heptanesia,” meaning “seven islands.” Many historians believe this is a reference to the seven islands that eventually formed Bombay. While Ptolemy’s mention is brief and lacks detail, it suggests that the area was known to ancient seafarers and may have had some recognition as a coastal landmark or minor port.

- Classical Phase (5th – 11th century CE): Under rulers like the Traikutakas, the Kanheri complex expanded significantly. Larger halls, intricate carvings, and detailed inscriptions appear in this phase, reflecting both growing religious importance and continued support from regional powers. Although direct control over the seven islands of Mumbai during this period is uncertain, the region was clearly integrated into the broader Konkan trade and religious circuits.

Thus, while direct evidence from the ancient islands themselves is limited, nearby centers and early global references like Heptanesia help confirm that Mumbai’s coastal geography was not unknown or irrelevant in ancient times. It was, even then, part of a larger economic and cultural world that shaped western India.

Cavel and Traces of a 4th-Century Settlement

One of the earliest documented finds from the islands of Mumbai comes from Cavel, a locality in present-day South Mumbai. In 1881, three coins were discovered here, dated to the late 4th century CE. Although the exact political authority that issued them remains uncertain, the discovery confirms that these islands were not isolated—they were already participating in active trade and economic circulation.

The name Cavel itself is said to derive from the Koli word "Kolwar," indicating the longstanding presence of the Koli community—traditionally fishermen—who are recognized as the earliest inhabitants of Mumbai's coastal landscape. Their settlements, scattered across the shorelines and estuaries, formed the human foundation of the region long before the rise of urban infrastructure.

The Shilhara Dynasty and Its Four-Century Rule

From approximately 810 to 1260 CE, the Shilhara dynasty ruled over large parts of North Konkan, including the seven islands that today make up the Mumbai City. Archaeological and inscriptional evidence of the Shilaharas has been found across the area, with notable discoveries at Parel, pointing to their active presence on the islands themselves. The dynasty was known for its religious patronage and civic infrastructure, commissioning the construction of temples, tanks, and embankments—many of which either survive today or are remembered through later reconstructions.

One of their most important contributions to the city’s landscape was the construction of the initial structure of Walkeshwar Mandir in 1127 CE. Although the temple was later destroyed during Portuguese rule, it was rebuilt in 1715 by Rama Kamat, a prominent local philanthropist from the Gaud Saraswat Brahmin community.

Despite their long rule, the Shilaharas faced repeated military threats. In the late 11th century, they suffered a significant loss of territory when the Kadambas of Goa pushed north during a period of internal discord. However, by 1136 CE, the Thana branch of the Shilaharas, with help from their relatives in Karad, managed to reclaim control over the region.

The dynasty again lost ground in 1161 CE, when the Solanki rulers of Gujarat launched an invasion and briefly occupied Mumbai and Thane. But in 1187 CE, the Shilaharas regained the territory once more, holding it for another several decades. Their rule finally came to an end in 1265 CE, when the last known Shilahara king, Someshwar, was defeated by Mahadeva of the Yadava dynasty.

The Figure of Bimb and the Rise of Mahim

Following the fall of the Silharas, the Yadavas of Devagiri appear to have administered Mumbai until the end of the 13th century. Though the Delhi Sultanate raided Devagiri in 1294, Yadava control may have continued until around 1300.

It is at this point that historical records begin to mention a ruler named Bimb. Described in the 1909 Gazetteer as a Brahmin, Bimb—also referred to in some sources as Bhimdev II—is said to have established his capital at Mahim and founded a new township called Mahikawati. The name is believed to have given rise to the modern toponym “Mahim.”

He is credited with granting rent-free lands to his followers and commissioning the construction of temples and civic buildings, though most of these early structures no longer survive. The Gazetteer (1909) declares him to be “the indisputable founder of Bombay” during this transitional period.

Interestingly, the Pathare Prabhus—one of Mumbai’s earliest recorded communities—are believed to have arrived with Raja Bimba during this time. As members of his entourage, they are thought to have settled in and around Mahikawati and contributed to the early shaping of local governance and social life. Their presence is still reflected in place names such as Prabhadevi and Prabhavathi.

Medieval Period

Up until now, it has been established that in 1300, Bombay was under the king Bimb. Historical records offer little detail on his eventual passing, but it likely occurred in the early 14th century. After his demise, his son ascended the throne, though the exact date remains obscure.

The next confirmed event in Mumbai’s history arrives in 1318 CE. Mubarak Shah I, son of the Sultan of Delhi Alauddin Khilji, launched a campaign, seizing Mahim and Salsette. By 1322, he had conquered Thane as well, expanding his dominion.

It's important to note the broader context. During this period, the Tughlaq Dynasty, which was the third dynasty to rule over the Delhi sultanate in medieval India, held sway over Deccan and Central India. Their focus, however, lay on securing the mainland and they neglected the security of the Islands. This power vacuum during the 14th century, allowed Bombay to slip back under Hindu rule for a brief period.

According to the Gazetteer (1909), Hindu control over Bombay and Salsette persisted until the 14th century's close, when foreign powers once again seized control under the name of the Gujarat Sultanate.

Gujarat Sultanate

The Gujarat Sultanate was established in 1407 by Zafar Khan or Muzaffar Shah I, a Tughlaq Governor of Gujarat who declared himself independent of the Delhi Sultanate. He controlled Gujarat as well as Salsette and Mahim. During this period, various other dynasties were being established in Central India as the Delhi Sultanate’s power was declining. The rise of the Native powers therefore, resulted in multiple conflicts between the Sultan of Gujarat and neighbouring powers until 1432 over the Islands of Bombay. The importance of Mahim as a military outpost was the major force behind the conflicts of major monarchies but post 1432 Gujarat established a strong control over Mahim. It can be assumed that these conflicts must have adversely impacted the resources of Salsette and Mahim.

During the governance of the Gujarat Sultan, Mahmud Shah I (1458-1511), certain events took place which were destined to exercise a powerful influence over Bombay. The Gazetteer (1909) records that:

“The Mirat-i-Sikandari mentions an attack by the Sultan upon certain Firangis who had created great disturbances in Mahim. These were undoubtedly the Portuguese who were just commencing to consolidate their power in Bombay, Salsette and Bassein.”

Although Mahmud Shah managed to defeat the Portuguese this time and managed to assert their power in Gujarat, the following years saw multiple attacks from the Portuguese over Mahim. In 1516, Portuguese commander Dom Joao de Monoy entered the Mahim Creek and defeated the commander of Mahim fort. The fort was the site of frequent skirmishes between the Portuguese and a Gujarati ruler before the island of Mahim was appropriated from Bahadur Shah of Gujarat by the Portuguese in 1534. Finally, the Portuguese consolidated their predominance in all the ports of the western coast from Diu to Goa. Hence, this marked the consolidation of Bombay under the Portuguese.

The Treaty of Bassein/Vasai

The treaty of Bassein was signed by Bahadur Shah of Gujarat and the kingdom of Portuguese in 1534, as the Sultanate of Gujarat could not sustain constant attack from the Portuguese. As per this treaty, Bassein, its territories, islands and seas including Bombay all came under the Portuguese. Thus by 1534, present-day Mumbai, Vasai, Virar, Daman & Diu, Surat and entire Goa had gone in the hands of the Portuguese.

The Portuguese, 1534 CE-1661 CE

The arrival of the Portuguese on the archipelago that would become Mumbai, stands as a pivotal moment in the city's history. This period, lasting just over a century, ushered in significant socio-economic changes that continue to resonate today.

The Portuguese influence is most evident in the city's former name, Bombay. Derived from their term "Bom Bahia" meaning "good bay," it reflects the region's natural harbor that first attracted them. During their rule, the Portuguese left a lasting mark by establishing a Christian presence through the construction of churches, some of which remain standing as testaments to this era. Additionally, their military presence is evident in the forts they built, further enriching the city's historical heritage.

Expansion of Christianity

The Portuguese followed a policy of political and religious expansionism in Mumbai. Vasco Da Gama, the first European to reach India, explains the Portuguese policy in the country as “Vimos buscur Christaos e especiaria,” meaning “We come to seek Christians and Spices”. Hence this period was characterized by the propagation of Christianity in India mainly through two Catholic religious orders—Fransiscan and Jesuit. According to the Gazetteer (1909), these two Catholic orders competed against each other in building churches and converting Indians into Christianity.

They went out into the rural region evangelising, gathering communities and providing for their spiritual sustenance. The San Miguel (St. Michael Church) in Mahim, which is one of the oldest churches in Bombay, was built by the Franciscan Portuguese in 1540. Some other churches that were built during this time and are still in existence include a chapel of ‘Nossa Senhora de Bom Conrelho’ at present-day Sion and ‘Nossa Senhora de Salvacão’ was built at present-day Dadar. In totality, according to the Gazetteer (1909) of Greater Bombay, around 10,000 people were converted to Christianity.

It is noteworthy that this imposition of religious uniformity upon Indians adversely impacted the trade practices of Bombay. The King of Portugal, who made no distinction between the Church and the State, failed to realize the important role that religious tolerance played in trade activities. Additionally, all political and economic preferment was given to the Christians while those who refused to accept the new faith were harassed and suppressed. The policy of religious intolerance inhibited Hindu merchants from settling in Bombay.

Furthermore, the nature of the Christianity that was prevalent in India was also changed by the Portuguese. According to the author Rita Rodricks (2020), the language of the Church in India, which was Syriac (language of the Syriac orthodox church), was replaced by Latin. In this process of ‘Europeanising’ the Indian Christians and ‘Latinising’ their Church, all traces of primitive Christianity in north Konkan were obliterated.

The Manor House

The principal architectural structures built by the Portuguese in Mumbai during their presence can be grouped into three basic social functions: defensive, religious, and residential structures. Out of these three, the construction of the religious structures has already been explained.

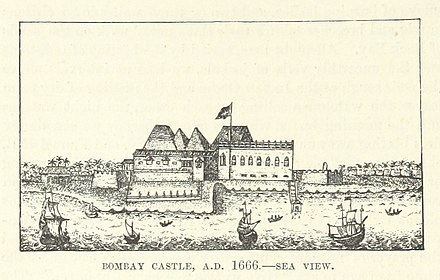

Coming to the defensive structures, the Portuguese tried to build a strong defensive position on the Island by constructing forts, watchtowers or fortified Manor Houses. One of the oldest and the most remarkable structures constructed by them for defense and administrative purposes was the Manor House (present-day Bombay Castle) in 1554. Garcia de Orta, a Portuguese nobleman, designed this building which went on to be the nucleus of the physical and administrative growth of the city.

Presently, the building houses the offices of the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief Western Naval Command and also has a sundial dating from the Portuguese era that, although not indicating 12 hours of a single day, does indicate particular periods that were significant to people at the time.

Khotachi Wadi: Mumbai’s Portuguese Architecture Village

While the Manor House was tied to the colonial elite, everyday Portuguese influence can still be seen in places like Khotachiwadi—a heritage village tucked into Girgaon. Founded in the late 18th century, the area was originally owned by a Hindu Brahmin, who sold plots to East Indian Christian families—local converts from Portuguese times.

These residents built their homes in a distinctly Portuguese architectural style, with open verandahs, sloped tiled roofs, and narrow winding lanes. As historian Andrea Baptista writes, after the fall of Portuguese rule in 1739, the East Indian community no longer had a protector. They held onto Portuguese cultural elements as a way to hold on to identity in a changing world.

Historian Andrea Baptista writes “After 1739 when the Portuguese fell to the Marathas, the community was without a guardian and they wanted a familial identity. By retaining elements of the Portuguese, they could build a bridge between the past and the present.”

Even today, despite modern construction creeping in, Khotachiwadi remains one of the few places in Mumbai where this layered cultural history is still visible.

Trade Policy of the Portuguese

The Portuguese weren’t just interested in land—they were after control of Indian Ocean trade. As historian Sifra Lentin explains, their goal was to redirect the spice trade away from Venice, which had long dominated the European import of Eastern goods.

Venice worked within a vast trading network that stretched from Egypt and the Ottoman Empire to Persia, India, and Southeast Asia. The Portuguese tried to break into this system in the early 1500s using naval power, cannons, and diplomacy.

And for a while, it worked. Between 1501 and 1506, trade records show a sharp decline in Venetian spice imports:

- From Alexandria, pepper shipments dropped from over 600 tons to just 135 tons.

- From Beirut, imports fell from 90–240 tons to a mere 10 tons.

But success was short-lived. The Portuguese overextended themselves, pouring too much money into forts, fleets, and religious missions. According to the 1909 Gazetteer, their aggressive push for conversions also disrupted trade. By the mid-1500s, Bombay's economy had shrunk to just a few exports like dried fish and coconuts. The grand commercial empire they envisioned never materialized—at least, not for the Portuguese Crown.

A Glimpse into the Contrast Between the 16th and 17th Century Bombay

In the early 16th century, Bombay’s seven islands were rich in natural resources. Coconut palms, jamun trees, and jangoma (Indian coffee plum) grew in abundance. The islands were not all the same—rice was cultivated in Mahim, while Mazgaon and Sion had large salt pans. Fishing was central to local life, with Koli settlements supplying fish to nearby towns like Bassein.

The population was organized into two administrative clusters, or kasbas:

- Mahim Kasba included Mahim, Parel, Vadala, and Sion.

- Bombay Kasba included Mazgaon, Bombay (now Fort), and Worli.

These divisions continued well into the early British period, showing that much of the island’s structure existed before colonial urban planning began.

By the mid-17th century, the Portuguese hold on Bombay was weakening. In 1634, the Portuguese chronicler Antonio Bocarro recorded a city in decline. Only eleven Portuguese families remained, with scattered groups of Indo-Portuguese, Kolis, Agris, and Bhandaris living on the margins.

Many local religious sites had been destroyed, and the northern islands were handed over to Jesuits, who pushed for widespread conversions. Military presence was minimal—Bocarro noted that the Manor House had no soldiers, and defense relied entirely on the local landlord. The Gazetteer summed it up bluntly, “By the mid-17th century, the island was arguably in worse shape than when the Portuguese first arrived.”

Still, the English saw potential. Bombay’s deep natural harbor and strategic location made it a perfect naval base. This interest led to key events:

- In 1612, the English fought the Battle of Swally (in Surat) to challenge Portuguese dominance at sea.

- In 1626, they attacked Bombay and burned the Manor House.

- By the 1650s, political shifts—like the death of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and the rise of Dutch naval power—weakened Portuguese influence even further.

Sensing an opportunity, the East India Company began pressing Portugal to cede Bombay, Versova, or Danda Rajapur. Within a few decades, the Portuguese hold on Bombay would end, and the British era would begin.

Colonial Period

In the year 1661, the island of Bombay was gifted to the King of Great Britain by the Portugal King as dowry for the marriage contract between Charles II of Britain and Infanta Catherine of Portugal. However, owing to some political strife, the island, together with its dependencies of Mazagaon, Worli, Mahim and Parel were finally acquired in 1665. In 1668, the islands were passed over by the British Crown to the East India Company, marking the beginning of more than 200 years of British rule in Mumbai City.

Gerald Aungier, The Founder of Bombay

The Island of Bombay, along with its dependencies—Mahim, Worli, Parel, Colaba, Little Colaba and Mazagaon, did not witness any development until the arrival of Mr. Gerald Aungier, the Governor of Mumbai from 1669-1677. Convinced of the potential of Bombay, he gave comprehensive proposals for the development of Bombay and therefore measures were initiated to fortify the island, build docks, and develop institutions for its civic and judicial needs.

In order to build a city on the Island, he invited experienced professionals for town planning and traders, artisans and others to build houses. Under him, the East India Company took measures that encouraged trade and constructed Custom Houses, Warehouses, Mole Stations, etc.

According to the author B.M. Phiroze (1910), Aungier’s watchwords were “Toleration and Progress” and therefore he allowed liberty to the native traders. He realised the importance of religious liberty in economic progress and thereby entered into a contract with “Neema Parrack”, an eminent merchant of Diu. By this contract, Parrack’s wish of settling in Bombay was granted by Aungier in exchange of liberty and security with respect to religious practices, trade and property on the island. His religious tolerance policy resulted in the immigration of Parsis, Armenian, Bohras, Jews, Gujarati banias from Surat and Diu and Brahmins from Salsette came to Bombay. The population of Bombay was estimated to have risen from 10,000 in 1661 to 60,000 in 1675.

Bombay Mint, 1670

Another notable development during his tenure was the Establishment of Mint in Bombay in 1670. Phiroze notes that “Mint had been established on the island as early as 1670, when Aungier was at the head of Government, and the earliest Bombay coins known at the present day are said to be those which were struck in this Mint in 1675.”

At the time when Aungier became the Governor of Bombay, the Islands of Colaba and Little Colaba, were beyond British jurisdiction. However, during his tenure he bought the two islands, making them British territories. The harbour was also developed, with space for the berthing of 20 ships. The prosperity and name of Bombay was further amplified in 1687 when the East India Company shifted its capital from Surat to Bombay.

One of the major achievements of Aungier was his attempt to fortify the island. Under him, Bombay's defenses received a significant boost. He transformed the Portuguese-built Manor House by starting the construction of the formidable fort known as Bombay Castle. Constructed from locally sourced blue stone from Kurla and red laterite from the Konkan, the castle boasted a commanding view, strategically encompassing the port, its surrounding bays, and the town itself.

The construction of Bombay Castle was finished in 1715 and it served as the seat of power, housing the Governor's residence within its walls. Gerald Aungier himself resided there. Today, the historic building stands as the headquarters for the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief Western Naval Command.

The First Anglo-Indian War, 1686 - 1690

The late 17th century witnessed the first Anglo-Indian war, a conflict between the English East India Company (EIC) and the Mughal Empire. Having secured a trade monopoly in western India, the EIC sought similar privileges in the eastern Mughal territories.

In this pursuit, William Hedges, an EIC representative, approached the governor of Bengal seeking trading rights in the eastern territories. The English were given tax benefits by the Mughal rulers of Bengal. However, the negotiations between the EIC and Mughals were disrupted by the arrival of a new governor, Sir Josiah Child, in 1685. His aggressive demands caused Aurangzeb to break off the negotiations. This led the EIC to cut and plunder the passage of Mughal ships in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, alienating Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and leading to a breakdown in talks and resulting in a war.

The conflict significantly impacted Bombay, an English port city established in 1668. By 1690, the EIC faced near-defeat at the hands of the Mughals. The strategic port faced a grueling 15-month siege (February 1689 - April 1690), as documented by historian Margaret R. Hunt. This period saw devastating destruction of the EIC's flagship settlement, with an estimated 80-90% of inhabitants either dying or fleeing.

Faced with this dire situation, the EIC surrendered and opted for peace negotiations. Their apology was accepted by Aurangzeb, who reinstated the company's trading privileges.

Piracy Disrupts Bombay's Trade

The last quarter of the 17th century was a turbulent period for Mumbai City. While tensions between the Mughals and the British East India Company shaped much of the political backdrop, another force disrupted the region more directly: piracy.

Among the many threats, the most formidable was Kanhoji Angre, the legendary Maratha admiral under Chhatrapati Sambhaji. As recorded in the 1909 Gazetteer, Angre’s fleet, composed of fast, oared warboats, terrorized merchant ships along the Konkan coast. His men—described as “vikings of the Konkan”—would bombard vessels with cannon fire before boarding and plundering them.

Angre primarily targeted European merchant ships, demanding what he called customary tribute but what the British saw as ransom. By 1715, his power had grown so significantly that British trade through Bombay was severely hindered. Naval battles became frequent, and the island remained in a state of constant siege—from both local resistance and European rivalries. As trade suffered, the City's population declined, its defenses remained neglected, and commerce stagnated.

Governor Charles Boone

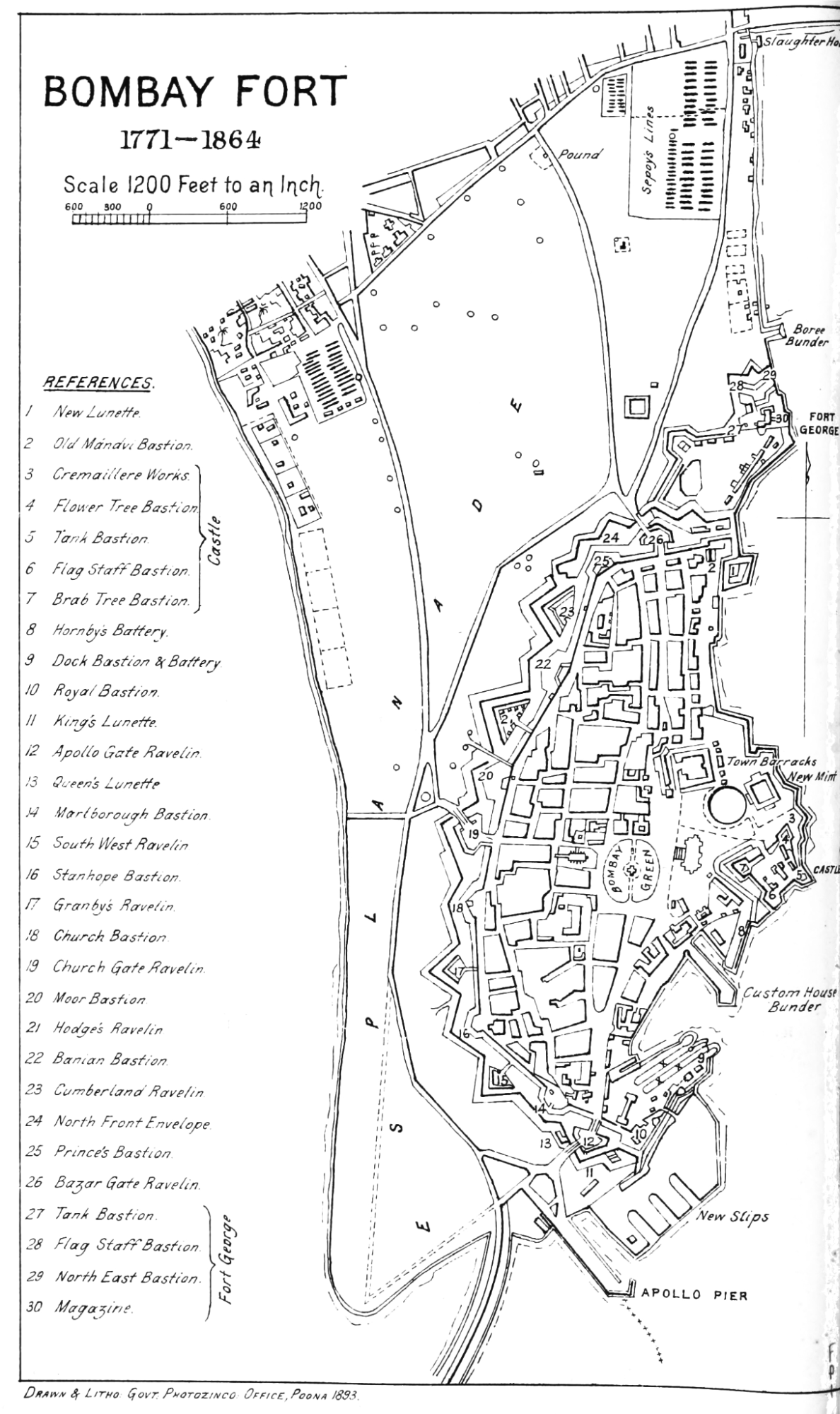

The turning point came in 1715, when Charles Boone was appointed Governor of Bombay. Tasked with restoring order and securing the island, Boone focused on two urgent goals: defense and development.

His most lasting contribution was the construction of a massive fortified wall around Bombay Castle, originally built by Governor Aungier. This wall stretched from Dongri Fort (present-day St. George Fort) to Mendham’s Point near Colaba, and included major fortified gates such as Apollo Gate, Lion Gate, and Churchgate—some of which still survive as landmarks today.

Recognizing Bombay’s strategic location by sea, Boone also established the city’s first Marine force, laying the groundwork for a naval presence that would prove essential in the coming decades. Beyond military measures, he actively encouraged urban development. Under his watch, the island saw the construction of new buildings and infrastructure, including the completion of St. Thomas Cathedral in 1718—Bombay’s first Anglican church and a key symbol of growing British presence on the island.

Relation between EIC and Local Powers (1722-1764)

Throughout the first half of the 18th century, the East India Company (EIC) followed a calculated political strategy: playing local powers against one another. Their main rivals in western India included the Siddis of Janjira, the Angres, and the Peshwas. By exploiting tensions between them, the Company bought itself time to grow in strength.

Yaqub Sidi and the Janjira Siddis

Initially, the EIC maintained a friendly relationship with Yaqub Sidi, using his naval force as a buffer against the Angrias. But by 1735, the Maratha Peshwa captured Sidi’s entire fleet, significantly weakening his position. Hoping to prevent a peace deal between the defeated Sidi and the rising Marathas, the EIC loaned Rs. 35,000 to Sidi—a move that temporarily kept him in check. Eventually, Sidi retreated to his strongholds at Jafarabad and Janjira, withdrawing from wider politics.

The Angres

Following Kanhoji Angre’s death in 1729, his successors inherited a divided legacy. Sekhoji and Sambhaji, his legitimate sons, split control of North and South Konkan, while Manaji, Kanhoji’s illegitimate son, also claimed power.

From 1722 to 1728, the Angres continued to attack EIC ships, severely damaging British trade. According to the Gazetteer (1909):

“So serious were the injuries inflicted by Manaji and Sambhaji, and so heavy the expense of fitting our ships to protect trade, that the Company were prevented from making their usual investments, and... began to anticipate an extinction of their commerce in Western India.”

Tensions between Manaji and Sambhaji soon surfaced, and the British capitalized on the rift. Quietly backing Manaji, they ensured that the Angrias were no longer united. The result: both factions began fighting the Company separately, weakening their effectiveness.

In 1735, Sambhaji dealt a heavy blow, capturing a large British merchant ship and seizing naval supplies. Further attacks followed in 1748 and 1752, prompting the British to ally with the Peshwas. This combined force eventually defeated the Angres, ending their maritime dominance.

The Maratha Confederacy

Unlike the Angres or Siddis, the Maratha Peshwa posed a long-term threat to British ambitions. The Peshwa ruled over a large and organized military force. As the Gazetteer notes, the EIC carefully maintained cordial relations with the Peshwa while quietly building up military and naval capacity in Bombay.

Between 1746 and 1760, the British reinforced Bombay Fort with bastions and batteries, and dismantled Dongri Hill fortress due to its close proximity to the town. According to the Gazetteer (1909):

“The military forces were increased by the enrollment of native troops; the dockyard was extended; a marine was established; communications with Salsette and the mainland were improved; sanitary administration was introduced; land was taken up for public thoroughfares.”

Through this combination of diplomacy, military investment, and urban planning, the EIC laid the foundation for its long-term dominance.

By the mid-18th century, the British had not only secured their position but had also begun reshaping Bombay into a true urban and commercial hub. Trade revived. Defenses were stronger. Political threats had been neutralized, or turned into uneasy allies.

The City’s population had grown to nearly 1,00,000, and the city was now connected to broader commercial circuits across western India and the Indian Ocean. What had once been a vulnerable, scattered colonial outpost was becoming the nucleus of British power on the west coast.

Making of Bombay in the 18th Century

In the 1720s, the British began to organize the urban space of Bombay as a part of which various building activities were taken up in Bombay. One of the most important tasks during this period was to connect the 7 islands. Hence, the work of draining and reclaiming land was taken up.

A plan was laid out according to which five embankments were supposed to be built that would drain water from the land at low tide. By March 1711, construction of 3 embankments had been finished: two at the north end of Parel and one between Parel and Mahim. By January 1712 the embankment between Mahim and Worli was also completed and only the Great Breach between Worli and Malabar Hill remained. This was, however, kept on hold.

During this period, to enhance the social development of the city along with the infrastructure, the British made efforts to attract business men and traders in Bombay. Various orders given by the English for exemption from payments of import and export duties for specific time periods acted as a major pull factor for migration of traders from Gujarat. Special encouragement was given to Parsis to facilitate the ship building industry as well as to supply textiles to the British merchants on a regular basis.

The Bombay Dockyard, established in 1732, was the finest shipbuilding yard in the country in the 18th and 19th centuries. Ships constructed at Bombay Dockyard in its heyday were said to be "immensely superior to anything built anywhere else in the world”. The Yard’s facilities were progressively augmented over the next 125 years and Bombay Dry Dock was constructed during the period 1750-1765. All these developments eventually resulted in higher population, better trade and a growing economy.

Relationship Between The Marathas and The EIC

The latter half of the 18th century was mainly concerned with determining the political relations between the EIC and the Maratha Government. Although they attempted to maintain good relations with the native powers in the beginning, the period under consideration later saw a shift in the relationship between the British East India Company (EIC) and the Maratha Empire. Initially, the EIC prioritized fostering friendly relations with the Marathas, focusing on consolidating their military strength in Bombay. However, upon William Thornby's appointment as Governor of Bombay in 1771, a more assertive approach emerged. Thornby aimed to showcase Bombay's newfound military power.

This opportunity arose due to internal conflict within the Marathas. Following Peshwa Madhav Rao's death, Raghunath Rao (his uncle) claimed the Peshwaship. He was swiftly ousted by supporters of the son of Madhav Rao. Capitalizing on this instability, Thornby pledged support to Raghunath Rao in exchange for significant land concessions, including territories near Bombay and several islands in the harbor.

In 1774, a treaty of alliance was signed between Raghunath Rao and the Bombay Council and the English waged war over Salsette and Thana. By the end of the year, both the territories had fallen in the hands of the English.

The following year, however, marked a turning point with the commencement of the first Anglo-Maratha war. The Bombay government's full participation in the war resulted in a devastating defeat for the British. The Marathas forced the EIC to agree to the Treaty of Wadgaon in 1779. This treaty stipulated the EIC's withdrawal of support for Raghunath Rao, the ceding of Broach and nearby islands, and safe passage for their remaining troops back to Bombay.

Despite the war's outcome, 1780 did hold some significance for the British. By withstanding the Maratha onslaught, Bombay had demonstrated its potential as a military force, albeit not yet a dominant one.

Developments in the Later Half of the 18th Century

St. George Fort

In 1769, the walls of the Bombay castle were further extended and Fort George constructed to strengthen the defenses of the area. The purpose of its construction was to provide defence in case of an unexpected attack from any of the adversaries like Siddis, Mysore, Portuguese or Marathas, or even the French. For this project, the hill on the Dongri Fort was razed and in its place the fort was built. In the following years, the area encompassing the fort and the castle came to be known as the Bombay fort and the main city was built around this area. It is noteworthy that in the present-day, the Fort area in Bombay corresponds to the fort region. In 1862, the fort was demolished.

Mazgaon Dock

In 1769, the English decided to build a dock at Mazgaon, the construction of which was finished in 1774. Over the years, it earned a reputation for quality work and established a tradition of skilled and resourceful service. In 1936, the company was finally incorporated as a private limited company and was taken over by the Indian government in 1960. Presently, the company has become one of the biggest shipbuilding yards in the country and the nation’s only shipyard to have built defences for the Indian Navy.

Local Administrative Changes

Apart from some big projects, this period also witnessed local administrative changes that had major socio-economic development in Bombay. In 1776, a regular ferry boat was started between Bombay and Thane making commuting easier for the locals. Various markets were built around the Bombay Fort, Town drainage planning was done, the police force was reorganized, and c.a. 1782, the ports of Bombay started trading cotton. Additionally, In 1785 a Marine Board was created and a Comptroller of Marine was appointed to manage Bombay’s increasing sphere of influence.

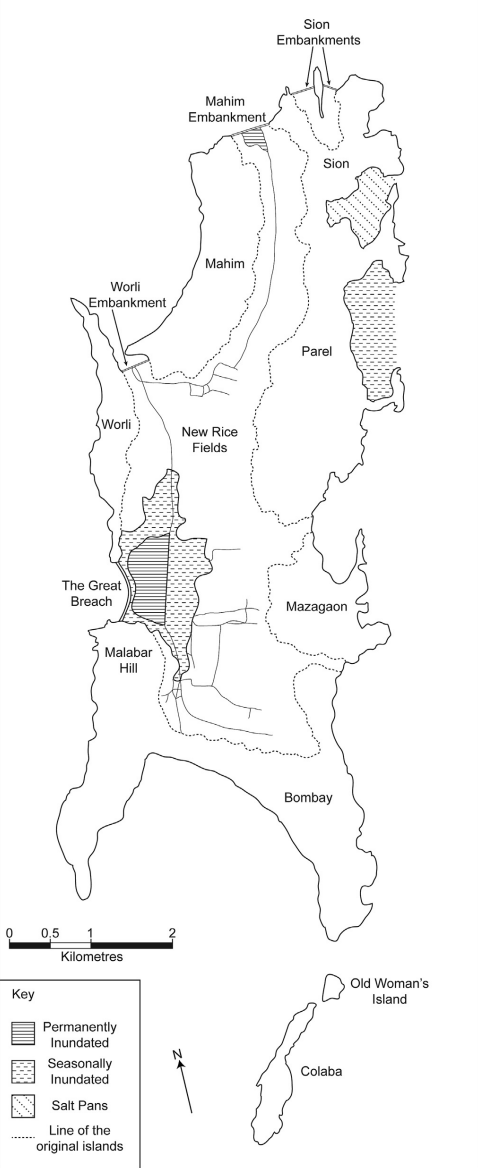

The Hornby Vellard and the Making of Mumbai City

Mumbai, as we know it today, began not as a single landmass, but as seven distinct islands—Bombay, Mazagaon, Mahim, Worli, Parel, Colaba, and Little Colaba—separated by tidal creeks and marshy lowlands. Of these, Bombay Island stood out for its size and strategic location, attracting early development and trade. It was home to the Bombay Castle, the administrative hub of the British East India Company, and several prominent churches. The neighboring Mazagaon Island, separated by a narrow creek, became the second most populated, while the other islands remained sparsely inhabited.

One of the biggest obstacles to urban growth was the inundation of low-lying areas during high tides, particularly the stretch between Bombay and Worli, which remained underwater for much of the year.

In 1782, Governor William Hornby proposed a bold solution: the construction of a seawall across Worli Creek to prevent flooding and unify the scattered islands. This project, later known as the Hornby Vellard, was both an engineering challenge and a transformative vision for Mumbai.

By 1784, the Vellard was completed, laying the foundation for one continuous landmass. It not only protected the city from high tides but also led to the reclamation of over 40,000 acres of land—what would become Central Mumbai. These reclaimed lands, previously unusable wetlands, sparked a surge in settlement, commerce, and construction, and helped reduce disease outbreaks linked to stagnant water.

The Hornby Vellard project marked the beginning of Mumbai's physical transformation into a city. Over the next few decades, additional causeways were built to bridge the remaining waterways and fully integrate the islands.

Sion Causeway (1798–1805)

Initiated by Governor Jonathan Duncan, this causeway connected Sion (in Mumbai) to Kurla (on Salsette Island), establishing a vital road for trade and mobility. Known also as the Duncan Causeway, it was the first major link between the city and its northern hinterlands.

Colaba Causeway (1835–1838)

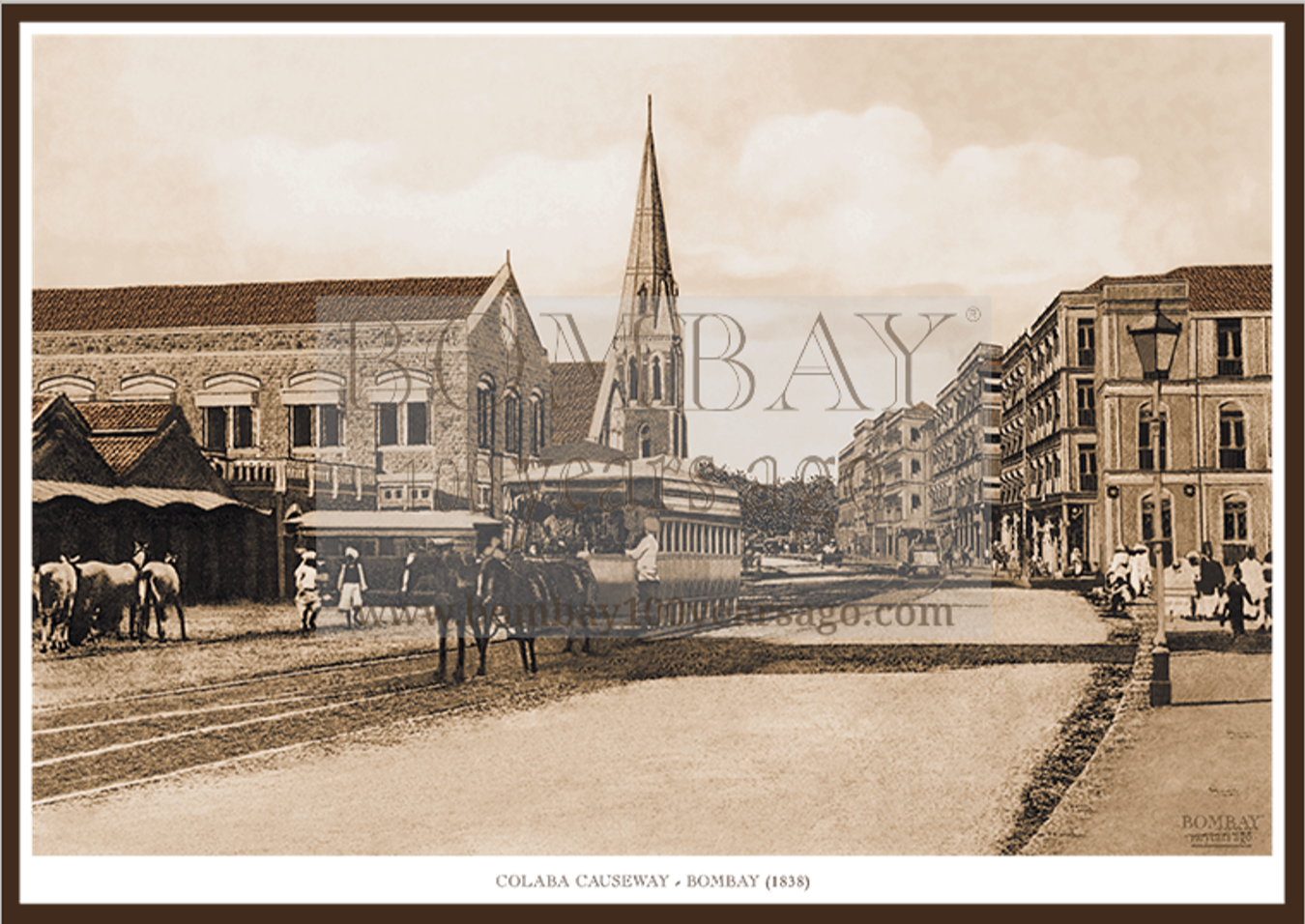

Completed under Governor Sir Robert Grant, this causeway finally connected Colaba and Old Woman’s Island to the mainland. With this, the long-standing vision of uniting all seven islands—first imagined in 1675—was realized. Today, Colaba Causeway is a vibrant commercial and cultural hub, but it began as a symbol of colonial engineering and urban ambition.

Mahim Causeway (1841–1846)

Built by the British with financial support from Lady Avabai Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, this causeway connected Mahim to Bandra, opening up North Mumbai for urban expansion. It remains a key arterial route between South Mumbai and the suburbs.

As the islands were stitched together, infrastructure followed. Roads like Grant Road, named after Sir Robert Grant, linked important areas such as Byculla and Chowpatty, reinforcing the city’s growing internal connectivity.

Mumbai’s Cotton Boom and the Birth of Indian Capital Markets

The early 19th century brought a dramatic shift in Mumbai’s fortunes—driven by cotton trade with China. As Chinese farmers began prioritizing tea and sugar cultivation, they increasingly relied on imported cotton, and Mumbai stepped in to fill that gap.

According to historian H.V. Bowen, cotton exports from British India soared. In 1805, a record 55.3 million pounds of raw cotton were shipped to Canton, China. Private traders, who had already been active since 1713, quickly recognized the opportunity to exchange cotton for sugar and other luxury goods, turning Mumbai into a major cotton entrepôt, overtaking Surat.

This economic boom attracted merchants, bankers, and skilled workers, especially from Gujarat and the Deccan, accelerating population growth and turning Mumbai into a cosmopolitan trading hub.

The Rise of Industry and India’s First Stock Market Crash

Mumbai’s growing role in global trade soon led to industrial development. In 1854, the city’s first textile mill—The Bombay Spinning and Weaving Company—was established. By 1860, six more mills had opened, cementing Mumbai’s status as a textile capital. A new working-class population emerged to meet industrial demands, marking the birth of industrial Mumbai.

But the American Civil War (1861–1865) brought unexpected consequences. As the U.S., the main supplier of cotton to Britain, became embroiled in war, Indian cotton became Britain’s primary source. In 1862 alone, India supplied 90% of Britain’s cotton needs. From 1861 to 1865, cotton exports from India soared from Rs. 16 crore to Rs. 40 crore.

This led to a speculative frenzy. Profits from cotton exports flooded into Mumbai’s young stock market, where traders invested heavily in banks, land companies, and new ventures like the Back Bay Reclamation Company. By 1864, Mumbai had:

- 31 banks

- 16 financial associations

- 8 land companies

- 16 press companies

- 2 shipping companies

- 20 insurance companies

- 62 joint-stock companies (compared to none in 1855)

Stockbrokers—initially a small group meeting under a banyan tree—grew to over 250. This informal network eventually formed the Native Share & Stock Brokers Association, which would become the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE)—Asia’s first.

When the American Civil War ended in 1865, American cotton returned to the global market. Prices plummeted, and Indian cotton lost its competitive edge. The stock market bubble burst, and companies with inflated share values collapsed. The Back Bay Reclamation Company, whose shares once traded at ten times their value, went bankrupt.

The crash wiped out fortunes, from wealthy investors to small traders, and served as a harsh lesson on the dangers of unregulated speculation. In response, the East India Company introduced Act XXVIII, which introduced rules for handling bankruptcies and liquidations.

Ironically, this financial crisis laid the groundwork for India’s modern financial sector. The once-informal group of brokers became an organized institution—the BSE, which today remains at the heart of Mumbai’s identity as India's financial capital.

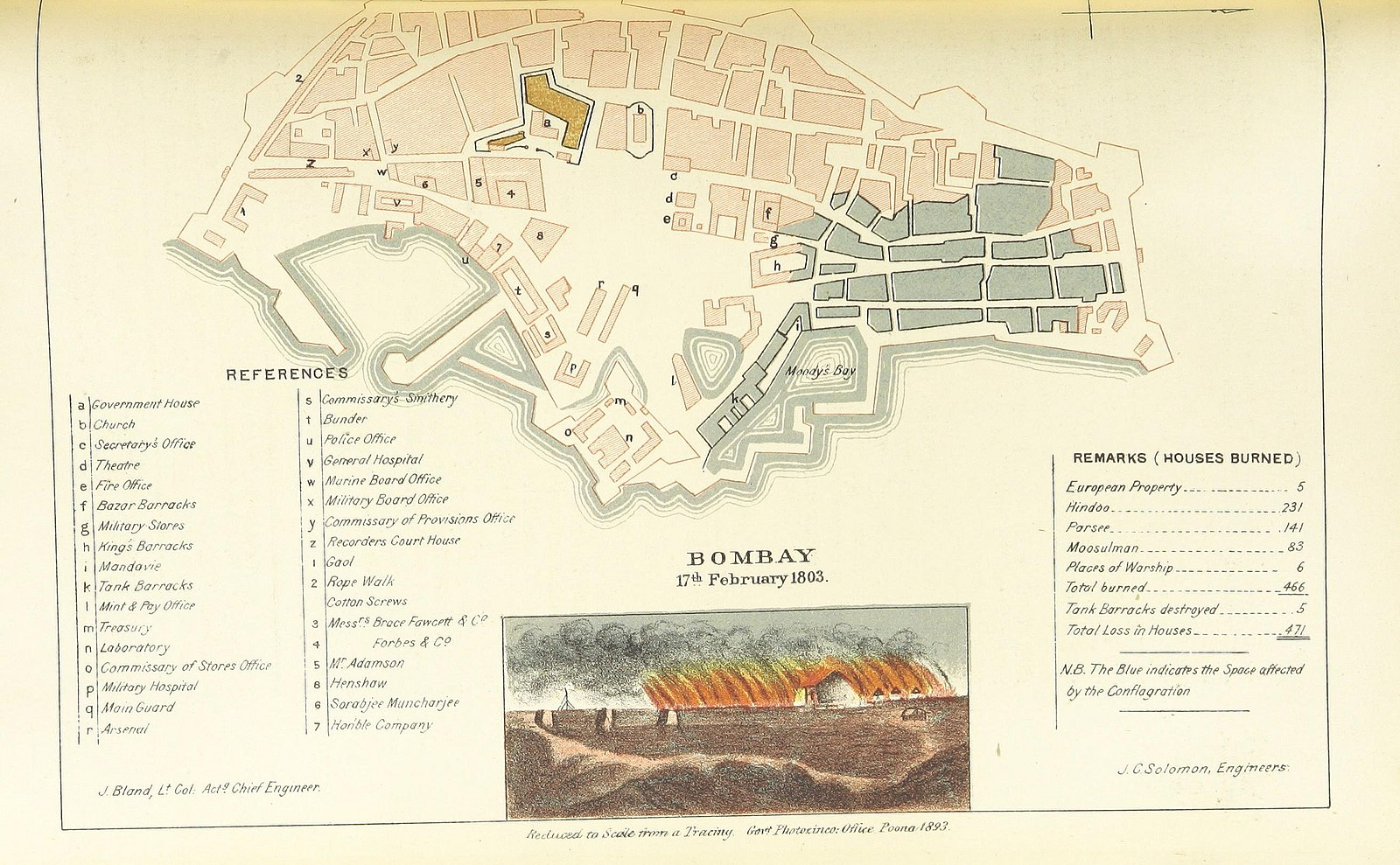

The Great Fire of 1803

By the early 1800s, Mumbai (then Bombay) had grown into a thriving port city. Its strategic location and growing political influence attracted a wide range of residents. Permanent communities of Parsis (Zoroastrians), Iranians, Arabs, and Europeans (mainly British and Portuguese) lived alongside a steady influx of traders and businesspeople. At the heart of this bustling city was "The Fort", built around Bombay Castle, which served as the administrative and commercial nucleus.

In 1803, disaster struck. A devastating fire broke out in the Fort area, ravaging homes, warehouses, and businesses. The destruction was so widespread that nine out of ten residents reportedly lost their property, and many lost their lives. It marked one of the darkest chapters in the city’s early urban history.

The aftermath of the fire caused economic and social upheaval. With thousands displaced, housing became scarce, and rents soared. Makeshift tents and temporary shelters sprang up around the city. The fire also disrupted supply chains, causing severe shortages of basic goods. Essentials like sugar and rock candy became difficult to find, and prices of everyday items skyrocketed.

Restructuring the Fort Area

In the wake of the disaster, the British East India Company (EIC) took swift and decisive action. Concerned about the safety of their military garrison, they imposed strict restrictions on rebuilding inside the Fort area. Their new urban vision called for a clear separation between military and civilian zones.

All damaged civilian structures within the Fort were scheduled for demolition. Going forward, only EIC officials and military personnel were allowed to construct or reside within its walls. This policy transformed what had once been the commercial and civic center of Bombay into a restricted, military-dominated enclave—a move that reshaped the urban geography of the growing city.

The End of the Maratha Threat

The year 1817 proved pivotal for Bombay and the British in India. The outbreak of the Third Anglo-Maratha War brought an end to one of the last major Indian threats to British control.

Although the war’s battles occurred outside the city, its impact on Bombay was significant. For decades, the city had lived under the looming fear of Maratha invasions. But in a series of decisive campaigns, the British exploited internal divisions among the Maratha Confederacy, defeating their armies one by one. The final blow came with the flight of the Peshwa from Pune, surrendering his territory and leaving his subjects under British authority. By mid-1818, the complete surrender of all Maratha leaders had solidified British control over most of present-day India.

A Road Through Bhor Ghat: Connecting Bombay and Pune

In 1819, a new era dawned for Mumbai City with the appointment of the Mountstuart Elphinstone as Governor. He recognised the critical role of improved communication in propelling Bombay forward. One of his earliest actions involved tackling the formidable Bhor Ghat, a mountain pass hindering trade between Bombay and the Deccan plateau. Elphinstone initiated the construction of a road through the pass, a project later completed by his successor, Sir John Malcolm. This improved the route significantly and eased the flow of goods and people. Later, the Great Indian Peninsula Railway laid a railway line from Mumbai to Pune (talked in detail further in the chapter).

Elphinstone’s vision extended beyond roads. By the 1830s, efforts were underway to establish regular steamship communication with England via the Red Sea and Mediterranean. In an era when sea travel still dictated the speed of empire and commerce, this was a revolutionary step toward reducing Bombay’s isolation and integrating it into the global economy.

Meanwhile, the aftermath of the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) had also reshaped Bombay’s prospects. With the Maratha power effectively dismantled and the Deccan pacified, the city no longer faced the persistent threat of conflict or piracy. This new stability proved invaluable for trade. Agricultural production in the Deccan flourished, and Bombay—with its expanding port facilities—became the natural outlet for this inland bounty.

By around 1825, Bombay’s export figures were soaring. The Deccan’s fertile lands yielded an abundance of commodities, especially cotton, which found eager buyers in overseas markets. The improved road through Bhor Ghat made it easier and faster to transport these goods to the coast, reducing logistical bottlenecks and increasing profitability.

At the same time, a global market shift was playing to Bombay’s advantage. A spike in the price of American cotton made Indian cotton a cheaper and more attractive alternative. Bombay quickly emerged as a key export hub, channeling vast amounts of cotton to British textile mills. This surge in demand spurred further cotton cultivation in the Deccan region.

The Mumbai Mint

Among the many developments during this period, the establishment of the Mumbai Mint was a landmark moment in the city’s financial evolution. Built between 1824 and 1830 by Captain John Hawkins of the Bombay Engineers, the Mint became the principal site for coin production under the Bombay Presidency, before being transferred to the Government of India in 1876.

In its early years, the Mint was a marvel of industrial efficiency. Powered by three steam engines, it produced nearly 1,50,000 coins daily, meeting the monetary demands of a rapidly growing economy. Its role only expanded with time. In 1919, a gold refinery was added, processing precious metal brought in from South Africa and Indian mines using the chlorine process. Just a decade later, a silver refinery was established, capable of handling up to 80 million ounces annually—further cementing the Mint’s central role in India's financial operations.

The next chapter in the Mint’s history began in 1964, when it issued its first commemorative coin—a tribute to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister. These special coins, designed to mark significant national events and figures, became a key part of the Mint’s cultural contribution. Today, the Mumbai Mint continues to operate as one of the most important mints in India.

Educational Advancement

Coinciding with the industrial and educational development was the advancement of education in Mumbai. Elphinstone College, one of the oldest colleges in the city, was established in 1823. It played a revolutionary role in shaping and developing the educational landscape of the island. Elphinstone College became a distinct institution, separated from the high school, on 1 April 1856. This year is officially considered to be the year of the establishment of Elphinstone College.

Flourishing Economy with Local Markets

By the year 1838 there were two large bazaars in the Fort, The China Bazaar and The Thieves bazaar. The latter was crowded with warehouses where European articles were sold at a small profit. There were other great bazaars that developed from which branched innumerable cross roads, each swarming with its busy crowds. The most profitable-trade carried on in these bazaars was the sale of toddy (Palm wine, an alcoholic beverage created from the sap of various species of palm trees). The consumption of this intoxicating beverage was to such a great extent that the Government had to issue orders forbidding the existence of toddy stores within a regulated distance of each other.

The Bombay Dog Riots, 1832

As Bombay underwent rapid economic and administrative transformation in the early 19th century, it also witnessed the first significant civil unrest in its modern history. Known as the Bombay Dog Riots of 1832, the unrest was sparked by a municipal campaign to exterminate the island’s growing stray dog population. Authorities viewed the animals as a public health threat, and a bounty system was introduced: eight annas per dog killed.

However, the policy deeply offended the Parsi community, who hold dogs in religious regard within Zoroastrianism. Reports soon emerged of dog catchers killing non-aggressive strays and even entering private homes to eliminate pets. The outrage was compounded by the timing—the culling coincided with a Parsi holy day, intensifying the perception that the authorities were disregarding religious sentiments.

On June 6, 1832, tensions erupted. Parsi residents attacked the dog catchers and stormed the magistrate’s court, demanding an end to the killings. The following day, protests escalated into a citywide shutdown, with Parsi businesses closing in solidarity, joined by strikes from segments of the Hindu and Muslim communities. Daily life in Bombay came to a standstill.

Rumors of British troops preparing to suppress the protests only strengthened resistance. Protesters blocked supply routes to army units, especially water and food, forcing the British to arrest several leaders. However, faced with overwhelming civic unrest and a breakdown of order, colonial authorities opened negotiations. A compromise was reached: stray dogs would no longer be culled, but instead relocated outside city limits. Protesters were released on the grounds that their actions stemmed from religious conviction rather than political defiance.

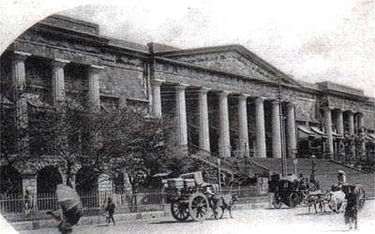

Asiatic Society of Mumbai Town Hall, 1833

The year following the riots, witnessed a remarkable development in the island's cultural heritage with the completion of the grand town hall. The "Literary Society of Bombay" came up with the idea for the Town Hall in 1811 but its construction was completed in 1833. The society raised commendable Rs. 10,000 through lottery, enough for a museum and library, but not the grand Town Hall that was envisioned. Undeterred, the society secured additional government funding, and in 1833, the Town Hall rose to its full glory.

Standing tall amongst Mumbai's heritage buildings, the Town Hall embodies the city's Victorian past. Once nicknamed "Tondal" in the 19th century, it now houses the esteemed Asiatic Society of Bombay (Mumbai), a public library brimming with knowledge. The Town Hall itself is a monument to the preservation of history, literature, science, and oriental arts.

Within its walls lies a treasure trove – a library and museum safeguarding ancient texts in Persian, Prakrit, Urdu, and Sanskrit. Visitors can marvel at a collection of 1,000 ancient coins, including the exquisite gold "mohur" once owned by the Mughal emperor Akbar. Even Dante's first edition of "Inferno" finds its home here, a testament to the Town Hall's diverse and invaluable collection.

The Bank of Bombay, 1840

As Bombay had become the main trade hub of the British empire and multiple markets had developed on the island, the government saw the need for a structural and organised banking system for smoother transactions. Hence, a major shift occurred in the financial landscape with the emergence of a more stable and formalised method of financial management. The Bank of Bombay, established in 1840, marked the beginning of this new era.

Parsi-Muslim Riot, 1851

The growing diversity of Bombay also brought with it periodic communal tensions. One of the most severe occurred in 1851, when a riot broke out between Parsis and Muslims. According to the Gazetteer (1909), the spark was a pictorial article allegedly depicting the Prophet Muhammad, pasted on the wall of Jama Masjid. As visual depictions are forbidden in Islam, this was perceived as a grave insult. The following day, mobs attacked Parsi homes and fire temples. Widespread violence and looting continued until a military curfew was declared.

Efforts to restore harmony culminated in a public reconciliation on 24 November 1851, when community leaders from both sides rode together in a carriage through each other’s neighborhoods, signaling a return to peace.

However, tensions resurfaced in 1874 when another article about the Prophet in a book titled Famous Prophets and Communities led to further violence. After a heated speech at Jama Masjid, mobs vandalized two Parsi fire temples, with participation from Sidis, Arabs, and Pathans. The police eventually quelled the unrest, arresting over seventy people. This incident highlights the religious sensitivities that existed in Bombay during this period.

The Great Indian Peninsula Railway, 1853

With trade booming, the colonial government sought better connectivity between Bombay and the Indian hinterland. The idea for a railway line had been floated as early as 1844, and in 1853, the first twenty-mile stretch to Thana was inaugurated—marking the birth of Indian Railways. The Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR) aimed to bridge Bombay with the Deccan plateau and the eastern coast, enabling faster movement of cotton, spices, and other goods.

One of the most ambitious—and tragic—engineering feats of the project was the extension through Bhor Ghat, connecting Mumbai to Pune. This section was fraught with labour unrest, disease, and fatalities. Over 24,000 workers reportedly died during its construction. The initial contractor’s harsh treatment of laborers led to riots and even the death of a European supervisor. After a government review, the contract was reassigned to Solomon Tredwell, who died shortly after arriving. His wife, Alice Tredwell, remarkably took over and completed the project in 1863—a rare feat for a woman in that era.

By the 1860s, GIPR was expanding further, joined by the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway (BB&CI). Together, these lines reshaped Bombay’s economic geography and connected it to the rest of British India like never before.

University of Mumbai, 1857

Amid these infrastructural developments, Bombay also established itself as a center of higher education. The University of Bombay was founded in 1857, modeled on the University of London, and was one of the first three universities in India. Initially, it functioned primarily as an examining body, affiliated with pre-existing institutions like Elphinstone College (1835) and Grant Medical College (1845), which surrendered their degree-conferring rights to the new university.

By 1904, the university expanded to include teaching departments and research programs, transforming into a comprehensive institution. Its evolution mirrored the intellectual and political awakening of the time, especially in a city that was becoming a hub of reform and nationalist ideas.

Adding to the campus was the Rajabai Clock Tower, completed in 1878. Modeled after Big Ben, the tower housed the university library and became a defining feature of the city skyline. In 2018, it was included as part of The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble of Mumbai, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

First War of Independence, 1857

Bombay played a relatively minor role in the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. However, the tremors of rebellion were certainly felt in this vital port city. Fear and suspicion hung heavy in the air, fueled by news of the uprising in Central India.

Charles Forjett, the Commissioner of Police, employed a ruthless strategy to maintain order. He relied on a network of informants to identify anyone expressing sympathy for the mutineers. Disguised as a local, he even resorted to spying on sepoys suspected of plotting revolt. According to the author Nina Martyris, one such instance involved Ganga Prasad, a sepoy suspected of harboring dissident meetings. Forjett, disguised, eavesdropped on a potential attack plan. He swiftly moved to arrest the leaders, who were subsequently court-martialed and condemned. On October 15th, In a public display of retribution, the two sepoy leaders were executed by being blown from cannons. This gruesome spectacle took place at the present day Azad Maidan and served as a stark warning to anyone harboring thoughts of rebellion.

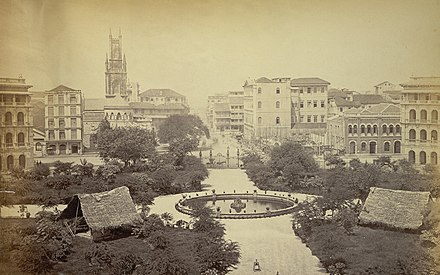

Reconstruction of the Fort Area

After the anxiety from the revolt of 1857 had calmed down, the government realised that defence was now not the main concern of Mumbai but trade was. Hence, the 1860s witnessed a pivotal shift in Bombay's destiny by the destruction of the fort. The dismantling of its fortifications symbolized the city's metamorphosis from a guarded outpost to a global commercial hub. This transformation unlocked a wealth of land for development, paving the way for a new era.

Governor Sir Bartle Frere, recognizing the city's evolving role, spearheaded the demolition of the obsolete fort walls. In 1872, this bold move transformed the local landscape and in an increase of area from 18 to 22 square miles.

According to the Gazetteer (1909), “simultaneously much energy wets displayed in the construction of new roads and the widening of old tracks, among the chief works of this nature being the widening and rebuilding of the Colaba Causeway in 1861-63, the commencement of the Esplanade, Rampart Row and Hornby Roads, the widening of Cruickshank and Carnac Roads in 1865 and 1866, and the completion of the Carnac, Masjid and Elphinstone overbridges in 1867.

More striking than new reclamation and communications were the great buildings and architectural adornments of the city. Hospitals, schools, libraries, museums were constructed. The Railway Companies opened new and extensive workshops at Parel ; the Gas Company laid down their plant in 1862; among other developments. One important development done during this time was the construction of the ‘Lord Elphinstone Circle’. The garden was planned in 1869 and completed in 1872 with well laid out walkways and trees planted all around.

Additionally, Sir Bartle Frere was also responsible for initialising the construction of various public and government offices. As per the Gazetteer (1909),

“They comprise the Government Secretariat, the University Library, the Convocation Hall, the High Court, the Telegraph Department, the Post Office, all in one grand line facing the sea. Other buildings in a similar style were built in other parts of the city, such as the Elphinstone College, the Victoria Museum, the Elphinstone High School, the School of Art, the Gokuldas Hospital, the Sailor's Home and others.”

Furthermore, this period witnessed a significant improvement in living standards. Enhanced street lighting, efficient drainage systems, improved sanitation, and a reliable piped water supply all contributed to a more comfortable and healthy environment for Bombay's residents.

Progress in Trade

The period between 1866 to 1870 saw an immense progress in trade. The following developments inevitably made Bombay the port city of India:

- 1866: The late 19th century saw a boom in steam navigation companies due to advancements in steamship technology. This trend reached India with the establishment of the Bombay Coast and River Stream Navigation Company in 1866. This company provided crucial passenger ferry and cargo services along the Konkan coast, significantly boosting domestic trade within India.

- 1869: A milestone year for international trade arrived with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. This revolutionary waterway drastically reduced travel times between India and European ports, facilitating trade connections with foreign countries.

- 1870: Further strengthening these international ties, a direct submarine cable was laid between Suez and Bombay in 1870. It was also in connection with the cable from Falmouth to Gibraltar, enabling faster communication and significantly enhancing foreign trade opportunities.

- 1873: This year marked the establishment of the Bombay Port Trust, boosting Bombay’s trade with the rest of the world. The opening of the Sassoon dock and the Prince dock for steam ships extensively revolutionised India’s trade.

Bombay Municipal Corporation

To manage this rapid expansion, the Bombay Municipality—created in 1865—was restructured in 1873 into a full-fledged Municipal Corporation. The body consisted of 64 members:

- 16 nominated by the government,

- 16 elected by local justices of peace,

- 32 elected by taxpayers.

The corporation took the lead in improving sanitation, urban planning, and civic infrastructure. Its importance was solidified with the construction of the Bombay Municipal Corporation headquarters, begun in 1884 and completed in 1893. It became a symbol of local governance in a colonial city.

Chattrapati Maharaj Shivaji Terminus

Bombay’s rising significance in trade and transportation also called for a grand railway terminus. In 1888, the iconic Victoria Terminus—now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus—was completed. Built as the headquarters for the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, it was both a functional hub and an architectural marvel, blending Gothic Revival design with Indian elements.

Today, it stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and remains one of Mumbai’s most recognizable landmarks.

Bombay Plague, 1896

The history of the period under consideration was overshadowed by the presence of the plague. The bubonic plague that struck Bombay in 1896 was nothing less than a nightmare that unfolded over several years. Its impact was catastrophic, transforming the bustling city into a ghost town.

According to the Gazetteer (1909), by October 1896, a mere eight months after the first case, a staggering 20,000 residents had fled the city, fearing for their lives. Within the next few months, the population had been halved, with 4,50,000 clinging to normalcy amidst the chaos.

While the plague wasn't unique to Bombay, the city bore the brunt of its devastation. Being a major port city, it served as the point of entry for the disease, hence the association of the epidemic with "Bombay" despite its wider impact. The densely populated dock area of Mandvi, with its warehouses and crowded housing, became the initial breeding ground.

The initial response to the outbreak was led by local officials. However, the death toll of over 33,000 within the first six months raised questions about their effectiveness. The drastic measures taken to control the spread, coupled with the rising panic, created a mass exodus of migrant workers from the city. Unfortunately, these fleeing individuals, unknowingly carrying infected fleas, became vectors for spreading the plague further across India. The city's already struggling economy, heavily reliant on its cotton mills and dock workers, suffered a major blow. The flight of labor caused a frenzy among mill owners, who resorted to offering exorbitant wages to attract replacements.

It wasn't until 1905-06, when the plague had subsided and the migrant workforce returned, that the city's textile industry began to recover.

It is noteworthy that the plague also caused riots in the city. Although the plague had infected the city, according to the author Cynthia Deshmukh (1988), people of Bombay did not believe that the plague was infectious. They were against the idea of their sick relatives being hospitalized. They wanted to tend to their relatives themselves and did not appreciate hospitalisation where the religious and caste practices were not applicable. Further, rumours had spread across the city that hospitalisation was an excuse by the British to kill people and thereby reduce the population of the city. Hence, “plague regulations were therefore treated as racist regulations being forced on the subject people, by an alien government".

Ultimately, the discontent that was created among the people of bombay resulted in riots. People started stone pelting at the hospitals; at several occasions ambulances were attacked; patients infected with plague would fight their way out of ambulances and hospitals. Gazetteer records that (1909) “cases like this often happened. In fact, in order to escape hospitalisation patients who found they had buboes just walked out of their homes and either tried to get lost in the city or tried to get back to their native homes in the villages in such large numbers that it was inferred that wandering was a symptom of plague.

However, by the end of 1898, the worst of the bubonic plague was over. Though cases continued till the 1920s, a sense of normalcy was eventually restored in Bombay. Meanwhile, the British administration also realised that forcing harsh measures against the wishes of Indians would only lead to more unrest and protests. Because of this, their plague policy slowly began to shift from one of intimidation and control to improving sanitation and cooperating with locals.

Overall, over 10 million lives in India are estimated to have been lost due to the bubonic plague in the 19th century. The plague years were pivotal in more ways than one. They exposed the limits of colonial rule, especially in matters of welfare and empathy. The harshness of British policies deepened anti-government sentiment among Indian elites and commoners alike.

These collective memories would later fuel the fires of nationalism, influencing a generation of leaders and reformers who had lived through Bombay’s darkest hours.

Cuff Parade

The plague led to the formation of the Bombay City Improvement Trust which was primarily endowed with the responsibility of improving the living and sanitary conditions of the city. Further, it was also responsible for developing the suburbs for residential purposes as the city area was getting overcrowded.

Therefore, the Trust reclaimed 75,000 square metres (807,293 square feet) on the western shore of Colaba. By 1906, a seafront road with a raised seaside promenade was completed, and called ‘Cuffe Parade’ after TW Cuffe of the Trust. Presently, the Cuff Parade is home to a collection of commercial and office high-rises.

The Hindu-Muslim Riot of 1893

The late 19th century saw rising communal tensions in Bombay, culminating in one of the city’s most violent episodes: the Hindu-Muslim riot of 1893. A key catalyst was the growing cow protection movement.

In 1887, the Gaurakshak Sabha (Society for the Preservation of Cows and Buffaloes) was established in Bombay, and similar organizations soon appeared across the Bombay Presidency. By 1890, according to historian Shashi Bhushan, these groups had become highly active—holding meetings, collecting donations from wealthy patrons, and coordinating with sister organizations across India. The movement was no longer confined to ideology; it had transformed into an organized campaign with political undertones.

Tensions came to a head in August 1893, when a group of Muslim worshippers, emerging from a masjid near Hanuman Lane, reportedly began shouting religious slogans. Some carried sticks, despite having entered unarmed. A clash broke out near a Hindu temple, and while police attempted to intervene, they were overwhelmed. Reinforcements eventually dispersed the crowd, but not before violence had erupted.

The riots spread rapidly across Bombay. Muslims attacked tramcars and vehicles; Hindus retaliated within an hour by assaulting Muslims and desecrating mosques. Though the worst of the rioting occurred over three days, tensions and hostilities lasted for over a month.

The toll was devastating:

- 81 people killed

- 700 injured

- 1,550 arrests

- 60 temples and 33 mosques damaged or destroyed

- Lakhs of rupees in property loss

Even after four weeks, officials could not claim that peace had been fully restored. The communal scars left by the 1893 riots would cast a long shadow over Bombay’s future.

The Swadeshi Movement in Bombay

As the 20th century began, Bombay became a major center of political awakening. Public discontent surged due to multiple colonial policies: harsh plague regulations, the restrictive Universities Act of 1904, and most significantly, the Partition of Bengal (1905).

In response, the Swadeshi Movement gained momentum, urging Indians to boycott foreign goods and adopt economic self-reliance. In Bombay, Bal Gangadhar Tilak emerged as a leading voice.

- Mass rallies and meetings to promote indigenous goods

- Engaging with business communities, encouraging them to trade locally and cut ties with British intermediaries

- Campaigns to educate the public about Swadeshi ideals and the dangers of economic dependence

Tilak even critiqued infrastructure projects like railway expansion, arguing that they primarily benefited British exports. He reached out to railway workers, raising awareness about how such projects facilitated colonial economic interests.

Thus, the Swadeshi movement in Bombay wasn’t just about boycotts—it was about building a national economic identity from the ground up.

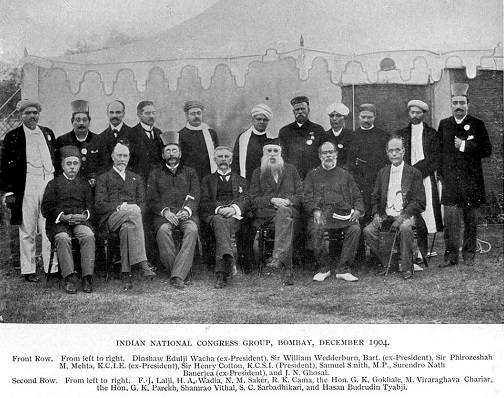

The Bombay Congress Session, 1904

The 1904 session of the Indian National Congress, held in Bombay, became a landmark moment. The session voiced strong opposition to Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, whose policies had come under intense scrutiny.

The Congress sharply criticized:

- The Partition of Bengal, which was seen as an attempt to divide and weaken nationalist sentiment in a politically active region

- Lord Curzon’s use of Indian revenue for military expeditions in Tibet

This session marked the beginning of the Congress's more assertive tone against British rule.

Opening of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel (1903)

Amidst political unrest and public health crises, Bombay also witnessed milestones in urban and cultural development. The most iconic among these was the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, inaugurated in 1903.

Commissioned by Jamshedji Tata, the hotel was India's first to offer electricity, American fans, German elevators, Turkish baths, and English butlers.