Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Nagardhan Fort

- Medieval Period

- Gondwana Kingdom

- Deogarh Gond Kings

- Ajanbahu Jatba

- Bakht Buland

- Chand Sultan

- Maratha Bhosale Kingdom

- Raghuji Bhosale I (1739–1755)

- Janoji Bhosale (1755–1772)

- Mudhoji Bhosale (1772–1788)

- Raghuji Bhosale III (1818–1853)

- Colonial Period

- “First War of Independence”, 1857

- Post 1857 territorial revisions

- A British Political Seat

- Agriculture

- Cotton Production

- Nagpur Oranges

- Famines

- Education

- Struggle for Independence

- The Nagpur Session of 1920

- Founding of RSS, 1925

- Quit India Movement, 1942

- Post-Independence

- Sources

NAGPUR

History

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

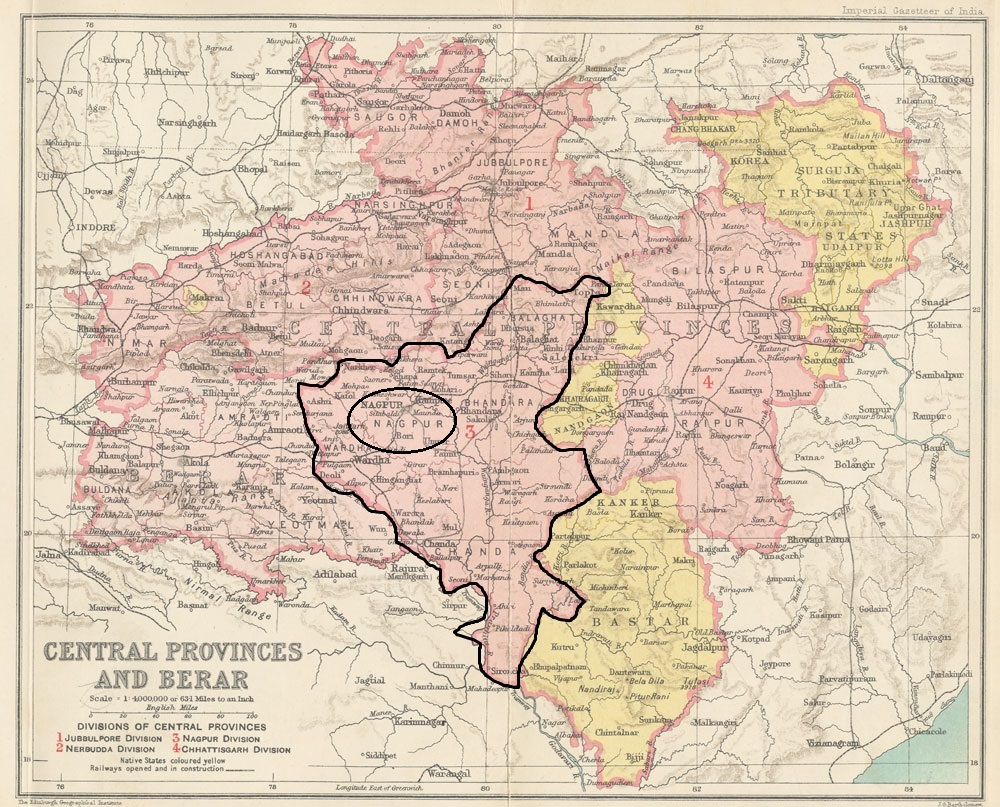

Situated in the eastern corner of the present Maharashtra, Nagpur stands as a district with a rich history. While it now constitutes an integral part of Maharashtra, it is intriguing to note that until the year 1960 it formed part of Madhya Pradesh, and under British dominion it was administered within the limits of the Central Provinces and Berar. However, the story of this district extends far beyond its recent administrative transitions, long before which, the region had witnessed human occupation for, it is believed, not less than three millennia. During the ancient period, it witnessed the influence of some of the greatest rulers, who all left an indelible mark on its cultural landscape.

In the earlier centuries of the historical period, the Nagpur region lay within the sphere of the Vakataka dynasty, one branch of which, it is believed to have established its capital here. Later, the Gond kings held sway in Nagpur for a substantial period, adding a distinct chapter to its historical narrative. In the eighteenth century, the ascendancy of the Maratha Bhosale house transformed Nagpur into the seat of a vigorous administration and a prominent centre in the politics of Central India. Throughout these changes of rule, the district’s fertile black soil sustained a thriving cotton cultivation, which, by the nineteenth century, had carried the name of Nagpur into the commercial markets of both India and Europe.

Etymology

The name “Nagpur” is commonly held to derive from the combination of two different words, Nag, referring to the river of that name which flows through the district, and Pur, signifying a city or town.

It is also popularly believed that prior to its present name, the place was known as Fandidrapura. The term ‘fana’ (फण), notably, is a Marathi word refers to the hood or head of a serpent, and possibly alludes to the river’s serpentine course.

Ancient Period

The district has a long history, with evidence of human habitation dating as far back as 8th century BCE. In 2008, the History department of Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University made significant discoveries supporting the existence of ancient civilizations. These findings were centred around megalithic stone circles unearthed at Drugdhamma, in present Mhada colony.

It was proposed that these circles served as human burial sites, with the monumental Menhir stones erected at their centres. This fascinating archaeological revelation shed light on the early burial practices of the region that date back over 3000 years.

Moreover, the research team drew intriguing parallels between the Menhir culture found in Nagpur and a similar stone sculpture at Shakti Sthal in New Delhi, associated with the samadhi of Indira Gandhi. This suggested a presence of this ancient stone culture across different regions of India, providing valuable insights into the shared historical practices that went beyond geographical boundaries.

Nagpur’s historical significance also finds place in the Ramayan, which is believed to have been composed circa 5th century BCE. The Gazetteer (1903), documented that the Ramayan references Nagpur in the context of Bhagwaan Ram’s journey through the Dandaka forest en route to Sutiskshna, a route on which present Ramtek was a notable location.

The popular belief suggests that Ramtek was a place where Shri Ram rested on their way to exile. Perhaps these traditions and beliefs contributed to the cultural and religious significance of Ramtek and the subsequent construction of a Ram Mandir there by Raghuji Bhosale, the Maratha ruler of Nagpur in the 18th century.

The early history of the district reveals the historical influence of the Ahirs or Abhiras, who briefly held sway over a significant portion of present Maharashtra. Their rule is noted to have succeeded the great Satavahanas, although it was for a relatively short-lived period. The Abhiras were traditionally associated with cattle rearing and were commonly referred to as Gaoli, with Gao translating to cattle.

Architectural remnants from this era substantiate the Abhiras’ presence. According to the Gazetteer (1903), the stone circles found in various villages are believed to be attributed to the pastoral Gaolis or Ahirs. Moreover, the Imperial Gazetteer (1903) highlights the analysis by Rev. Stephan Hislop who was an educationist, evangelist and geologist. He suggested that the Abhiras were potentially outsiders, possibly originating from Central Asia. This provides a glimpse into the dynamic interplay of cultures and migrations that have shaped the historical landscape of Nagpur.

According to Hislop, “The vestiges of an ancient Scythian race in this part of India are very numerous. They are found chiefly as barrows surrounded by a circle of stones, and as stone boxes, which when complete, are styled kistevans, which if not previously disturbed, have been found to contain stone coffins and urns. If these remains in truth belong to a race of nomadic herdsmen who spread over the country and reduced it to subjection, they may have been immigrants from central Asia like the Sakas who were living in India at about the same period. These were pastoral nomads of the Central Asian steppes who were driven southwards by tribes stronger than themselves and entering India established themselves in the Punjab and at Mathura, Gujrat and Kathiawar. The calendar in common use in the Maratha districts is named after them and was instituted by a prince of the Sakas in Gujrat in 169 AD.”

The classical age of Nagpur reveals the historical imprint of the Vakatakas, who held sway from the 3rd to the 6th centuries. Although historical sources from this period are limited, it is widely believed that Nagpur was part of the expansive territories ruled by the Vakataka Rajput kings. Their dominion extended across the Satpura plateau and Berar regions.

According to the Gazetteer (1903) there has been a significant discovery dating back to the 8th century – a copper plate found at Ragholi in the Balaghat district. This discovery was made by Mr. CE Low, the Deputy Commissioner. Hira Lal, the Assistant Gazetteer Superintendent, provided the translation and commentary on this copper plate. The inscription on this grant references a line of kings who claimed possession of the entire Vindhya region, a term that historically encompassed the Satpura hills. This discovery not only sheds light on the territorial extent of the Vakataka rule but also emphasizes the historical and cultural significance of Nagpur within the broader context of the Vakataka dynasty's influence over central India during the classical age.

Following the Vakatakas, the influence of the Rashtrakutas over Nagpur endured for approximately two centuries. Founded in the mid-8th century by Dantidurga, Nagpur likely fell within the dominions of the Rashtrakutas, a dynasty that emerged around 750 CE. The Gazetteer (1903) notes that one of the four significant copper plate grants associated with this dynasty was discovered in the vicinity of Nagpur, specifically at Deoli in present Wardha. The Deoli plate, dating back to 940 CE during the reign of King Krishna III, holds historical importance. It documents the grant of a village named Talapurumshka in the Nagapura-Nandvardhan District to a Kannada Brahman. This inscription not only provides insight into the territorial administration of the Rashtrakutas but also highlights the cultural and administrative dynamics of the Nagpur region during this historical period. The discovery of such copper plates contributes valuable historical evidence, connecting Nagpur to the broader narrative of the Rashtrakuta dynasty's rule in central India.

As indicated by the Sitabuldi stone inscription dated in the year 1087 CE, Nagpur fell under the Chalukyas. They ruled as a vassal of Rashtrakutas. The Gazetteer (1908) highlights this historical shift, noting that the inscription mentions both the name of the Western Chalukya king and a Rashtrakuta king named Dhadibhandal. This inscription provides important historical evidence of the evolving political dynamics and power structures during this period, showcasing the transition of the Rashtrakutas from a ruling dynasty to becoming vassals under the Chalukyas.

By the 11th century, Nagpur transitioned from the feudatory rule of the Rashtrakutas to being under the governance of the Paramara or Ponwar kings of Malwa. According to the Gazetteer (1908), this shift is evident in the Prashasai or stone inscription of Nagpur dated to 1104-05 CE. Historical records indicate that the influence of these kings extended not only to Nagpur but also into Berar, the Godavari region, and even the Carnatic, as they pursued conquests.

Around a century earlier, Munja, the seventh ruler of the Paramara line, achieved notable success by defeating the Western Chalukya king Taila II sixteen times. However, Munja's seventeenth attack met with failure, and he was defeated after crossing the Godavari, Taila's northern boundary. It is believed that the legacy of this period is reflected in the existing Ponwar caste of the Nagpur region.

There is historical evidence suggesting that Nagpur was under the Yadavas. The names of two kings, Simhana and Ramachandra, along with the term “Yadaa Vansa” can be deciphered. Intriguingly, a stone inscription from 1402 CE by Brahmadeva of the Raipur branch of the Haihayas states that Brahmadeva's father was Ramachandra, whose father was Simhana. This same genealogy appears in another inscription from 1413 CE. It becomes evident that the kings mentioned in the Ramtek inscription were ancestors of Brahmadeva, suggesting that perhaps before Haihaya forces reached Ramtek in the 14th century, Nagpur was under the Yadavas. However, scarce historical records during this period makes it difficult to provide a detailed account of the events, rulers, and developments that shaped Nagpur's history between the 12th and the16th centuries.

According to Mr. Hira Lal, Assistant Gazetteer Superintendent, the district was under the Control of the Haiyhaya Rajput dynasty of Chhattisgarh after the Yadavas. He claimed this based on his interpretation of an inscription found at Ramtek.

Nagardhan Fort

Nagardhan fort, which is just 7 km south of famous Ramtek (mentioned above) is built during the time when Vakatakas control the district at around 4th–5th Century CE. The area was a key fortified city, playing an important role in the region's history and defense. According to the Gazetteer (1908), excavations at Nagardhan have revealed coins, pottery, and artifacts from different periods including Vakataks, confirming its long-standing historical presence. The discovery of a Vakataka-era seal supported the claim that it was a major city in ancient times.

The Gazetteer (1908) records that Mr. Hira Lal, a historian, theorized that "Nagar" (Nagardhan) was historically called Nandivardhan. The importance of Nagapura-Nandivardhana (Nagardhan) is supported by another copper plate inscription from 940 CE, which mentions this location. This indicates that Nagardhan had historical significance over centuries.

The fort was strengthened and fortified by the Bhosales of Nagpur later, primarily for military defense, administration, and as a royal residence. However, after Nagpur’s annexation in 1853, the fort declined in importance and was no longer used for strategic purposes. Today, it stands as an important historical monument linked to the Bhosale dynasty and Nagpur’s history.

Medieval Period

Gondwana Kingdom

From the 16th century onwards, Nagpur fell under the exclusive influence of the Gondwana or Gond Kings. The Gondwana kingdom, ruled by the Gond community, encompassed the core areas of the eastern part of Vidarbha in Maharashtra, including Nagpur. The most powerful Gond rulers controlled Gondwana (meaning "Land of the Gonds") which included areas such as, Garha-Mandla (Jabalpur, MP), Deogarh (Chhindwara, MP), Kherla (Betul, MP), Chanda (Chandrapur, Maharashtra) and Sambalpur (Odisha).

Deogarh Gond Kings

Among the different constituent kingdoms of Gondwana, Nagpur thrived under the rule of the Deogarh Gond kings, who emerged as one of the most formidable and enduring powers. The Gond Kings held sway over Nagpur for a long four centuries, establishing their capital in the city and making the present district a significant seat of power. The kingdom in Nagpur was believed to be founded by the King Ajanbahu Jatba, also called Gond royals of Deogarh. It was expanded by Bakht Buland Shah and Chand Sultan in the 17th century. Bakht Buland Shah (1650s–1700s) was argued to be a visionary Gond king who transformed Nagpur and the Deogarh kingdom into a flourishing economic and cultural center. They resisted external forces when the subcontinent witnessed the expansion of the Mughal influence. However, there was a brief period of indirect Mughal influence through these Rajas.

Ajanbahu Jatba

The stories recorded in the Gazetteer (1908) about the founder king Ajanbahu Jatba, suggests that he was born from a virgin mother under a bean plant. He was the 8th descendant of the dynasty’s founder. According to local tradition, as an infant, he was protected by a Cobra that spread its hoods over him during the heat of the day when his mother had to attend to her work. Growing up, Jatba went to Deogarh (perhaps in present Odisha) and served under the twin Gaoli kings, Ransu and Ghansur. He earned their favour by lifting the large castle gate off its hinges with his bare hands. He became the founder of Gonds of Deogarh whose kingdom encompassed the present Nagpur district.

According to local belief, his epithet “Ajanbahu” refers to the length of his arms, which extend down to his knees. His political emergence has an interesting legend. It holds that Jatba faced a challenge during the Diwali festival when he was ordered to slaughter a Buffalo without having a proper weapon, only possessing a wooden cudgel. In a dream, the Devi assured him that his lucky stick would transform into a finely tempered sword at the crucial moment. Following her guidance, Jatba slaughtered the Buffalo, then mounted the royal Elephant, killed the kings, and established himself in their place.

It is mentioned that Emperor Akbar, during whose reign Jatba ruled, visited Deogarh and Jatba too made a visit to Delhi. The records of British officer Mr. Craddock, note that the kings mentioned before Jatba are considered by some as potentially fictional additions. This was likely done to give the house of Deogarh a longer and more prestigious lineage. In the end, Jatba, described as a petty local Zamindar, is recognized as the first authentic member of the Gondwana dynasty, marking the beginning of its historical record.

Bakht Buland

Bakht Buland, the 3rd or 4th in descent from Jatba, reigned in 1700. He was a dynamic and influential figure during his time. Bakht Buland meant “of high fortune” in Persian. He is known for his notable decision to go to Delhi and enter the service of Emperor Aurangzeb. The story surrounding him indicates that he performed a noteworthy feat, gaining the favor of the Emperor. As a result, Aurangzeb persuaded him to renounce the practices associated with Bhimsen (possibly a community devta) and embrace the Islamic faith. Subsequently, Bakht Buland was recognized as the Raja of Deogarh under his new name. According to the Gazetteer (1903), he was an able administrator and a ruler. He attracted many cultivators and artisans to the Nagpur countryside through generous land grants.

According to the British Officer, Sir Richard Jenkins “He employed indiscriminately Muslims and Hindus of ability to introduce order and regularity into his immediate domain. Industrious settlers from all quarters were attracted to Gondowana. Many thousands of villages were founded. Agriculture, manufacturers, and even commerce made considerable advances. It may, with truth, be said that much of the success of the Maratha administration was owing to the groundwork established by him. Bakht Buland added to his dominions from those of the Rajas of Chanda and Mandla and his territories comprised the modern districts of Chhindwara and Betul and portions of Nagpur, Seoni, Bhanadara, and Balaghat.”

Chand Sultan

Chand Sultan, who succeeded Bakht Buland as ruler of Nagpur, is known for constructing a walled city in Nagpur which his predecessor started. It was built by uniting twelve small villages previously known as Rajapur Barsa or Barasta, laying the foundation for the city’s historical legacy. His reign continued the liberal policies of his predecessors, contributing to a considerable increase in the wealth of the region. According to the Gazetteer (1903), this prosperity made Nagpur an attractive acquisition for the Maratha power that had already established itself in nearby Berar.

Chand Sultan’s demise resulted in a historical episode illustrating complex political dynamics and power struggles in the region during that period. Upon Chand Sultan’s death in 1739, Wali Shah, an illegitimate son of Bakht Buland, seized the throne. In response, Chand Sultan’s widow sought assistance from Maratha leader Raghuji Bhosale of Berar on behalf of her sons, Akbar Shah and Burhan Shah. With Raghuji Bhosale’s support, Wali Shah was removed, and the rightful heirs were placed on the throne. Following his intervention, Raghuji Bhosale departed for Berar upon reaching a negotiated settlement that included compensation for his role. According to the Gazetteer (1903), the treaty involved Raghuji receiving eleven lakhs of rupees and several districts along the Wainganga River. Additionally, Raghuji was appointed as the intermediary for all external communications of Nagpur.

Maratha Bhosale Kingdom

The Bhosales ruled the Nagpur Kingdom from the early 18th century. During the period, they emerged as one of the most influential members of the Maratha Confederacy, playing a key role in the conquest of extensive regions in central and eastern India.

Raghuji Bhosale I (1739–1755)

Raghuji was the first and most distinguished of the Bhosale rulers of Nagpur who expanded Maratha influence in the region. Under his rule Maratha influence expanded up till Central and Eastern India, particularly Orissa, Bengal, and Chhattisgarh. According to the revised Gazetteer (1977), Raghuji was a trusted general under Shahu Maharaj, the Chhatrapati of Satara. Around 1730, Shahu Maharaj appointed Raghuji Bhosale as the Sarsenapati (governor) of Berar, instructing him to establish Maratha rule in Vidarbha and beyond.

When Raghuji arrived in the region, Nagpur was under Chand Sultan. Raghuji Bhosale led Maratha forces against the Gonds and captured Nagpur in 1739, making it the capital of his newly established kingdom. The conquest of Nagpur was a key turning point, as it gave the Marathas a stronghold in Central India.

Describing the extent and might of Raghuji, the Gazetteer (1908) records that “the countries under his dominion or paying him tribute may be generally described as extending east and west from the Bay of Bengal to the Ajanta hills and north and south from the Narmada to the Godavari. His cavalry was principally composed of horses. His standing force was about 15,000, but was liable to be augmented every year according to the exigencies of the moment. Bold and decisive in-action Raghuji was the perfect type of a Maratha leader. He saw in the troubles of others only an opening for his own ambition and did not even require a pretext for plunder and invasion. The reign of Raghuji is chiefly important in the history of Nagpur because with him came that great influx of the Kunbis and cognate Maratha tribes which altered the whole face of the country and the administration of the land, as well as the language of the people.”

It should be noted that the mid-19th century was characterised by a complex political landscape, shaped by dynamic regional power dynamics. During this period, the re-emergence of Marathas and the quest for independence from the Mughals by the Nizams of Hyderabad underscored the shifting political landscape. Concurrently, the decline of the once-mighty Mughal Empire unfolded, creating a void that various regional entities sought to fill. Moreover, the gradual but significant expansion of the English East India Company added a pivotal dimension.

Janoji Bhosale (1755–1772)

Around 1755, it was in this complex political landscape that Raghuji’s son Janoji succeeded him. The Nizam's incursion into his territory prompted Janoji to ally with the Nizam, enticed by the promise of Sardeshmukhi (a form of revenue) and the freedom to plunder his brother in present Chandrapur district. Despite abandoning the Mughals, Janoji refrained from aiding the Peshwa, head of the Maratha confederacy. The Nizam's victorious march led them to the Maratha capital Poona in 1762, where together, they advanced to the city. Janoji, however, decided to shift his allegiance. Lured by the promise of a territory that could generate a revenue of 32 lakh, Janoji turned against the Nizam and colluded with the Peshwa’s forces. This joint effort resulted in the decisive defeat of the Nizams.

The Pune based Peshwa (see Pune for more), aggrieved by Janoji's duplicity, joined forces with the Nizam in 1765 to avenge the sack of Pune. Their combined armies advanced to Nagpur, setting it ablaze and compelling Janoji to relinquish a significant portion of the gains from his earlier betrayal. Two years later, Janoji, once again in arms against the Peshwa, faced ultimate failure. The ensuing treaty, made in April 1769, solidified Janoji's dependence on the Peshwa. He committed to providing a contingent of 6000 men, personal attendance whenever summoned by the Peshwa, and an annual tribute of 5 lakhs of rupees.

The internal and regional rivalry for territorial control continued until the British took advantage of it and took over Nagpur. Despite this, the Nagpur Kingdom reached its highest peak. According to the district Gazetteer (1908), practically the entirety of the present Central Provinces and Berar besides Odisha and some of the Chota Nagpur states was under Raghuji II by 1787. The revenue of these territories was about a crore of rupees. Raghuji’s army consisted of 18,000 horse and 35,000 infantry, of which 11,000 were regular battalions beside 4,000 Arabs. His field artillery included about 90 pieces of ordnance. The military force was for the most part raised outside the limits of the state, with the cavalry being recruited from Pune while Arabs and adventurers from Northern India and Rajputana were largely enlisted in the infantry. Up to 1803, the Maratha administration was, as a whole, successful.

However with the onset of the 19th century and the Second Anglo-Maratha War, the Bhosales suffered territorial losses. In 1803, Raghuji II allied with the Peshwas against the British in the war. However, the British emerged victorious, and Raghuji was compelled to cede Cuttack, Sambalpur, and a portion of Berar. Mudhoji Bhosale (1772–1788) strengthened Nagpur as a political and military center and his successor Raghuji Bhosale II’s (1788–1816) reign saw increasing British interference in Maratha affairs.

Mudhoji Bhosale (1772–1788)

In the history of Nagpur, Mudhoji II or Appa Sahib played a pivotal role. He tried to resist British control but was defeated. Subsequently it was under him that Nagpur came under British rule in 1818 after the Third Anglo-Maratha War.

The Battle of Sitabuldi was fought in Nagpur, India, on November 26 and 27, 1817, between the British East India Company and the Maratha forces of Appasaheb Bhonsle, the King of Nagpur. The British won the battle, which took place on the twin hills of Sitabuldi. Following the victory, the British constructed Sitabuldi Fort on the site.

After the demise of Raghuji Bhosale II in 1816, his son Parsaji was swiftly ousted and killed by Mudhoji II. Within two years, i.e, in 1818, the Third Anglo Maratha War occurred. Following this, the Bhosale Maharaja reluctantly agreed to a subsidiary alliance. This alliance resulted in Nagpur becoming a princely state under the rule of the British crown. Subsequently, it was governed by a commissioner appointed under the authority of the Governor-General of India, marking the downfall of the Bhosales in Nagpur. From 1818 onwards, the Nagpur kingdom ceased to be a Maratha confederate state and instead became a protectorate of the East India Company.

Raghuji II succeeded the Mudhoji and expanded their territory. His reign was marked by the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars.

Raghuji Bhosale III (1818–1853)

Raghuji III was the fifth and last independent Bhosale ruler of Nagpur, but his rule was largely influenced by British supervision. From 1818 to 1830, even before Nagpur's formal annexation by the British, the actual administration was in the hands of the British Resident, Sir Richard Jenkins. This was part of the broader British control following the defeat of the Marathas in the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–18).

According to the Gazetteer (1908), Raghuji III was a maternal grandson of Raghuji II and was adopted by his grandfather’s widows. He was officially recognized as Raja Raghuji III, following the same terms as Appa Sahib in 1816. During his early years, a regency was established, headed by Baka Bai, the widow of the second Raghuji, who took care of the young ruler, while Sir Richard Jenkins administered the state through appointed officers. In 1830, under the residency of R. Cavendish, Raghuji III was allowed to assume actual governance, four years after the departure of Sir R. Jenkins. Raghuji III was allowed to rule, but forced to mostly follow the administrative structure laid down by Jenkins. His reign is portrayed as relatively peaceful and well-managed. Raghuji III died in December 1853 without any biological or adopted heir, leading to Lord Dalhousie’s annexation of Nagpur under the Doctrine of Lapse. This marked the end of the Bhonsale rule and the integration of Nagpur into British India.

From 1853 to 1861, Nagpur was governed by a Commissioner under the Government of India, and in 1861, it became part of the newly formed Central Provinces, with Wardha district included.

Colonial Period

The British took formal control of Nagpur in 1853 and ruled it as the Nagpur Province under the administration of a British commissioner appointed by the Governor General.

“First War of Independence”, 1857

This period in general, was marked by the general disruption by events related to the Indian Revolt of 1857 which started as mutiny. The residents of Nagpur united in an effort to collectively resist British intervention in the district, playing a crucial role in shaping the district’s narrative during that period through their collaborative actions.

According to the Gazetteer (1908), there was a belief that Nagpur had no contact with the rebellious centres of the Bengal army before the outbreak. However, as soon as news of the unrest reached the city, signs of dissatisfaction appeared. Although pamphlets (chapadis) had been distributed, their significance was not widely understood, and they did not attract much attention. However, historical research has shown that this regular local behaviour was interpreted rather as a sign of conspiracy and added to the “colonial anxiety” during and after the revolt.

According to the Gazetteer (1908), another event that marked the defiance of the local community against British rule. Towards the end of April, some influential Muslims in Nagpur displayed an unusual opposition to the government's orders regarding burials outside the city. The government responded decisively by prohibiting intra-mural burials, and despite compliance, there were subtle indications that the British government's authority was being questioned.

The behaviour of the community in Nagpur was closely monitored from that point onwards. In May 1857, Mr. Plowden served as Commissioner, and Mr. Ellis as Deputy Commissioner of Nagpur. The troops stationed in Nagpur included a regiment of irregular cavalry, largely composed of local Muslims, a battery of artillery, and a regiment of Hindustani infantry. Additionally, Kamptee was garrisoned by two regiments of infantry and one of cavalry from the Madras army, along with two European batteries. It is to be noted that this period was marked by a situation of heightened alert and precautionary actions taken by British authorities in Nagpur to address unwarranted suspicious local activities.

The British administration lived under continuous fear which the historians have described as “imperial anxiety.” The Gazetteer (1908) states that there was formulation of a plan for a “rebellion” in conjunction with the regular cavalry and the Muhammadans in the city. Secret nightly meetings were held, and Mr. Ellis, who had discovered them, along with Scotch Church Missionaries, warned of the growing unrest in the public mind. The planned uprising was scheduled for the night of June 13th, with a fire-balloon launch serving as the signal to the cavalry.

Suspicious movements detected in the cavalry lines in Nagpur led to an urgent investigation. This investigation revealed that the regiment was preparing for some sort of action, as they were seen saddling their horses. The situation escalated, prompting Mr. Ellis to take precautionary measures. However, a few hours before the scheduled time, one squadron of the cavalry received orders to march for Seoni. This unexpected development disrupted the conspirators' plans. In response, a messenger (daffadar) was sent to alert the infantry about the change in plans. Unfortunately for the conspirators, the messenger was immediately captured and confined by the first person he approached.

Simultaneously, Major Bell, the Commissary of Ordinance, took charge of securing the arsenal. Loaded cannons were strategically positioned to control the entrance and approaches. Meanwhile, a small detachment of Madras sepoys went to Sitabuldi hill, setting up the guns in position. Their conduct reassured authorities that the Madras troops had not been influenced. However, until reinforcements arrived from Kamptee, the situation hinged on the disposition of the irregular infantry and artillery.

The officer leading the infantry was incapacitated due to injuries from a tiger encounter, and the sole remaining officer was absent from the station. In response, Lieutenant Cumberlege, the Commissioner's Personal Assistant with prior experience in this regiment, assumed temporary command. He found the regiment voluntarily gathered on the parade ground, displaying readiness to follow any orders. The battery of artillery, under the command of Captain Playfair, exhibited an equally commendable spirit.

Post 1857 territorial revisions

Post 1857, several changes were made in the Indian subcontinent with regard to British administration. One of the major developments was the direct control of India by the crown. In this process, it was felt that the geographical isolation of the Nagpur district and its detachment from the headquarters of any local government created administrative challenges. These difficulties prompted the decision to establish a new province in 1861. This was a strategic reorganisation done to address the administrative complexities that arose from the detached nature of the Nagpur territory.

This led to the creation of a larger administrative entity known as the Central Provinces and Berar,with Nagpur becoming its integral part.

A British Political Seat

Nagpur served as the capital of the Nagpur Division under the British. In 1861, with the formation of the new Central Provinces and Berar, a new administrative framework was put in place. The Central Provinces were formed through 19th-century British acquisitions from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, encompassing a significant portion of present-day Chhattisgarh, along with parts of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra states. The Nagpur province was recreated into a division and merged with this larger administrative boundary.

Agriculture

In 1909, agriculture was a substantial economic activity in Nagpur. According to the Gazetteer (1908), Nagpur had a significant amount of land actively used for agriculture, ranking it eighth in terms of cropped area among the combined provinces.

Cotton Production

The production of raw cotton played a pivotal role in influencing the economic and commercial prosperity of the district. Nagpur is, in fact, renowned for its cultivation of cotton, with it standing out as a significant cash crop.

The Gazetteer (1908) records the increasing cotton cultivation in the area. In 1863, the area in which cotton was cultivated was 70,000 acres. This number increased to 1,49,000 between 1892 and 1894, and further to 4,76,000 acres in 1905-06. Further emphasising the exponential growth, the Gazetteer stated that “in recent years, the increase in this crop has been extraordinary.”

According to the Gazetteer (1908), the “Empress Mill” was inaugurated on 1 January 1877, by the Central India Spinning and Weaving Company, under the management of the late Mr. J. N. Tata. The mill was named so to mark the day when Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India. The Mill, in 1908, had 75,000 spindles and nearly 1,400 looms, with an employment of approximately 4,300 operatives.

Raw cotton from Nagpur was exported to international markets, including Europe, and was predominantly sold to Continental mills. Cotton yarn, on the other hand, is sold in the Central Provinces and Bengal, while the cotton cloth of the Empress Mills is sent all over India and in small quantities to China, Japan and Burma as well. Apart from cotton, oilseed was another major cash crop, contributing to the economy of the district.

Nagpur Oranges

The reputation of Nagpur oranges goes back to the 1900s. It was recorded in the gazetteer that “Nagpur oranges have an established reputation. The outer peel is easily removed and the inner skin is very thin, while for juiciness and sweetness, they cannot easily be matched.” In 2014, oranges from Nagpur earned the Geographical Indication (GI) tag, giving its growers exclusive rights to use the term ‘Nagpur Orange’. The history of these oranges, as recorded by a scholar R.S Joshi in Agricultural Journal of India 1907, states that “Tradition relates that the orange was first introduced into Nagpur by the Bhosale Raja, Raghuji II, about the end of the 18th century from Aurangabad and Sitakol.”

On the process of orange cultivation, Joshi states that “during the period it was noted that there was only one variety, locally named Santra. All the plants are propagated by budding, growth from seed not being practised. The stock generally used is the sweet lime (Mitha nimbu), and less frequently the common citron (Zamburi). Buds of the orange grafted on the latter stock produce trees which yield fruits with a very loose skin, while those on the former stock have a more closely adhering jacket, showing that the stock has a distinct influence on the bud. The seeds are sown in baskets and subsequently twice transplanted into seed-beds and nursery plots, and in two years’ time, are ready for budding, which should be done between November and January.” Further the record says that “The first flowering is called “Mrigbahar” because it occurs in the nakshatra or lunar month of Mrig or the deer. The second is called “Ambia-bahar” because it occurs in February at the same time that the mango tree or “aam” flowers.” It was recorded that about 600 tons of oranges may have been exported annually to outside areas, such as Bombay and Calcutta, and remaining bulk was consumed locally.

Famines

Nagpur has a historical backdrop of famines, with the earliest recorded famine in the district dating back to 1818-19. By this time, Nagpur was already under the British. The primary trigger was the failure of the monsoon, followed by excessive rain in the cold weather, leading to acute distress and famine conditions. This crisis resulted in a significant loss of life, and it is documented that many impoverished cultivators in Nagpur resorted to selling their children into slavery.

In the years 1892 to 1896, according to the Gazetteer (1908), abnormal rainfall, particularly in September and October 1892, was followed by excessive rain. However, from 1893 to 1896, the rainfall in the first three months of 1893 was substantial, with 81 inches received compared to an average of 53 inches. Nevertheless, in the critical months of September and October 1896-97, which had significant influence over harvest outcomes, less than 2 inches of rain were received. This led to a partial failure of the autumn harvest and a reduction in the area sown with cold-weather crops.

In 1897-99, a bumper harvest was recorded, but in 1900, the absence of rain between the end of September and the hot weather resulted in a shortfall in spring crops, even though the autumn harvest was satisfactory. Overall, the harvest in 1900 was 92 percent of the normal yield. In 1899, cloudy and rainy conditions in April and May were considered ominous signs. The monsoon failed completely that year, with the rainfall from June to August measuring only 31 inches, compared to an average of 32 inches. From October to January, no rainfall was recorded. The annual precipitation was less than a third of the average in each tahsil, except in Ramtek, where it was about half.

Education

Nagpur is recognized for its educational institutions. Hislop College, established in 1882, stands as the first and foremost college in Nagpur. It was affiliated to the University of Calcutta until 1904, and later to Allahabad University. At present, it is affiliated to Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University. The college was named after Scottish missionary Stephen Hislop (1817–1863), who was a noted evangelist, educationist and geologist who worked around Nagpur extensively. In June 1885, the second college in Nagpur, Morris College, emerged as the first government college in the city.

Struggle for Independence

Nagpur was actively involved in the political movements against British rule in India. The district witnessed various phases of resistance and participation in the struggle for independence. One notable event was the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1920, where the non-cooperation movement was launched. Further, it holds historical significance for the foundation of early 20th century socio-cultural organisation.

The Nagpur Session of 1920

Nagpur played a significant role in the initiation of the non-cooperation movement in India. The Nagpur session of 1920 of the Indian National Congress (INC) marked a crucial moment where the decision to launch the non-cooperation movement was made. The non-cooperation movement was a key phase in the Indian independence struggle led by Mahatma Gandhi. This movement, aimed at non-violent resistance and non-cooperation with British authorities, seeking to attain self-governance and independence for India.

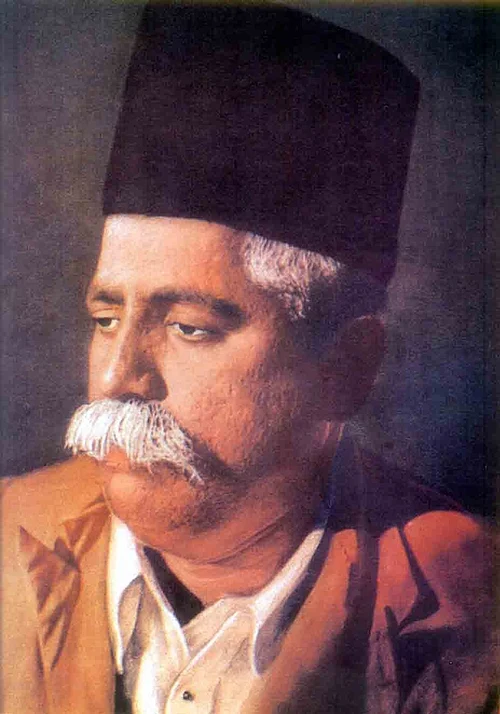

Founding of RSS, 1925

Nagpur played a crucial role as the birthplace of this influential socio-cultural organisation during the early 20th century. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was founded in 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar in the city of Nagpur. The founding of the RSS took place in the backdrop of India’s struggle for independence and the socio-political changes occurring in the country. Dr. Hedgewar was influenced by the thoughts of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who emphasised the importance of promoting a united Hindu society as a means of achieving national strength. He established the organisation with the primary aim of promoting the idea of a united and strong Hindu society. The city became a hub for the early activities of the RSS.

Quit India Movement, 1942

The Quit India Movement in 1942, which called for an immediate end to British rule in India, also saw active participation from Nagpur. The people of Nagpur, like many other parts of the country, contributed to the larger political struggle by engaging in protests, civil disobedience, and other forms of resistance against British colonialism.

Post-Independence

Following Indian Independence in 1947, the Central Provinces and Berar underwent administrative rearrangement. It transitioned into a province of India, later becoming the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh in 1950, with Nagpur as its capital. However, during the state reorganisation based on linguistic criteria in 1956, the Nagpur region and Berar were transferred to Bombay state, which, in 1960, was divided between the present states of Maharashtra and Gujarat.

One notable event that took place during this period was Dr Ambedkar’s embracing of Buddhism in Nagpur. At a formal public ceremony on 14 October 1956, in Nagpur, B. R. Ambedkar, along with his supporters, embraced Buddhism, initiating the Dalit Buddhist movement, which continues to be active.

Sources

1966. Maharashtra State Government Directorate of Government Printing, Stationery and Publications.http://www.maharashtra.gov.in/english/gazett…

Anjali Marar. 2020. “1,500-Year-Old Sealing Unearthed near Nagpur Reveals Power of Vakataka Queen.” The Indian Express. January 23, 2020.https://indianexpress.com/article/india/1500…

B. Bhukya. 2012. “The Subordination of the Sovereigns: Colonialism and the Gond Rajas in Central India, 1818–1948.” Modern Asian Studies.

Census of India. 2011http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/dch…

G. B. Malleson. 1984. An historical sketch of the native states of India. 3000-year-old burial site unearthed. The Times of India.http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/Cities/30…

Menon, Mini. 2021. “The Rise of the Vakatakas (3rd CE - 6th CE).” PeepulTree. April 27, 2021.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

R.V Russel ed. 1908. Central Provinces District Gazetteers: Nagpur District. Times Press, Bombay.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

Rakesh Sinha. 2003. Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (in Hindi). New Delhi: Publication Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India

S.B. Chaudhuri. Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India.

Tapan Basu, Tanika Sarkar. 1993. Khaki Shorts and Saffron Flags: A Critique of the Hindu Right. Orient Longman.

Websites Referred: Nagpur District: Official Website, Wikipedia,.Maharashtraweb.com,Nagpur, Official Website.http://www.maharashtraweb.com/Cities/Nagpur/…

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.