Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- The Legend of Renuka Devi and Mahur

- Birthplace of Bhagwan Dattatreya

- Kandhar and the Mahabharat Tradition

- Political Powers & Dynastic Traditions

- Traces of the Satavahanas at Shiur

- Shiur Caves & the Vishnukundins

- Rashtrakutas and their Capital at Kandhar

- Chalukyas of Kalyani and the Hottal Inscriptions

- The Yadavas of Devagiri and Mahurgad

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate & the Nanded Fort

- Bahmani Sultanate and the Rise of Mahur

- Guru Nanak Dev at Nanded

- Raje Udaram and the Mahur Jagir

- Prince Khurram at Mahur

- Famine of 1629–30

- Rai Bagan and the Defence of Mahur

- Administrative Importance Under the Mughals

- Maratha–Mughal Conflict and Nanded’s Strategic Role

- Guru Gobind Singh and the Story Behind Hazur Sahib

- Decline of Mughal Power and Rise of the Nizam

- Maratha–Nizam Rivalry and Local Engagements

- Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountcy

- The Hatkars and the Rebellion of 1819

- The First War of Independence, 1857

- Hyderabad Samajik Sudhar Sangh

- Post-Independence Era

- Sources

NANDED

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Nanded district is an administrative district located in the eastern part of Maharashtra. It lies predominantly on the northern bank of the Godavari River and forms part of the Aurangabad Division. The district was established in its current form in 1960, following the reorganization of states and the dissolution of the former Hyderabad State. Historically, Nanded is part of the Marathwada region and has been a significant hub due to its location along ancient inland trade and migration routes.

The area is mentioned in the Mahabharat, where it is believed that the Pandavas passed through during their period of exile. Throughout its history, Nanded has come under the rule of several major dynasties, including the Satavahanas, Vishnukundins, Chalukyas of Kalyani, Rashtrakutas, and later the Bahmani Sultanate. The region is also noted for its connection to the Mughal Empire; Prince Khurram (later Emperor Shah Jahan) is said to have taken refuge in the area with his son Aurangzeb during a period of political turmoil. Nanded is also historically significant as the place where Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Guru in Sikhism, spent his final days and affirmed the Guru Granth Sahib as the eternal Guru.

Etymology

The name Nanded originates from the anglicized Sanskrit word ‘Nanditat,’ with multiple theories explaining its etymology. One theory links it to Nandi, Bhagwan Shiva’s vahan, who is believed to have performed penance on the Godavari’s banks, giving rise to ‘Nandi tat.’ Others propose that the district’s name is derived from the nine rishis known as Nand who also meditated along the Godavari banks, resulting in ‘Nand tat.’ Additionally, the name may have originated from being the boundary ‘tat’ of the nine Nanda rulers of the Magadha Empire, evolving over time into ‘Nanditat’ and eventually ‘Nanded.’

Ancient Period

The Legend of Renuka Devi and Mahur

One of the earliest glimpses into Nanded’s early history emerges from sites across the district that have been connected with long-standing religious traditions. Among these, Mahur, located in the northeastern hills of the district, has grown into an important yatra centre. The town occupies a cluster of three hills, each crowned by a Mandir. These have remained central to local traditions for centuries and continue to draw visitors from across Maharashtra.

The most prominent site is the Renuka Devi Mandir, located on the first hill. Renuka Devi is regarded in regional tradition as the mother of Parashurama, (who is regarded as one of the ten incarnations of Vishnu). She is also closely linked to the Rishi Jamadagni, who is said to have resided in this area. The association of Renuka with Mahur rests upon a tradition preserved in local belief; this widely circulated account describes that while engaged in her daily task of drawing water, Renuka momentarily lost focus, which so displeased her husband, the Rishi Jamadagni, that he commanded their son, Parashurama, to put her to death. He is then believed to have brought her back to life through a boon. The current Mandir marks the spot where her head is said to have fallen.

The worship of Renuka at Mahur is of considerable antiquity. References to the town appear in classical Sanskrit literature, including the Devi Bhagavatam and the Devi Gita, where it is referred to as Matripura or Matapur, both signifying “the town of the mother.” These references are commonly cited in support of Mahur’s long-standing association with Devi worship.

Renuka Devi is worshipped here in her maternal form, and the Mandir is widely recognized as one of Maharashtra’s three and a half Shakti Peethas. The present structure is believed to date to the Yadava period (circa 9th–13th century CE), although the worship of Renuka at this site likely predates it. The annual Vijayadashami fair remains one of the most significant events in the town's calendar.

Birthplace of Bhagwan Dattatreya

Mahur is also associated with the birth of Dattatreya, who is considered a unified form of the Hindu trinity, Bhagwan Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. He is said to have been born to Rishi Atri and his wife Sati Anasuya, who are believed to have lived in Mahur. The second of Mahur’s three hills is occupied by the Datta Shikhar Mandir, which stands at the highest point in the town and is dedicated to Dattatreya.

The third hill contains the Atri-Anasuya Mandir, where Atri, Anasuya, and Dattatreya are all venerated. Anasuya is particularly remembered for her spiritual discipline. A commonly recounted account describes how the Bhagwan Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva, disguised as ascetics, tested her resolve; her conduct is held up in various texts as exemplary.

Kandhar and the Mahabharat Tradition

Another place tied to the early history of the district is the town of Kandhar. According to oral accounts, Kandhar is identified as part of Panchala, the kingdom of Draupadi, wife of the Pandava brothers. The surrounding valley is known as Pandavdara, and is believed to mark the place where Draupadi was married to the five Pandavas.

Though the Mahabharat itself names no specific location for this episode in the Deccan, the identification of Kandhar with Panchalpuri is deeply rooted in local belief, and continues to form part of the historical memory of the district.

Political Powers & Dynastic Traditions

Though early records are sparse, the political history of Nanded district may be traced in broad outline through its connections to wider developments in the Deccan. Located between the Godavari basin and the uplands of Vidarbha, the region served as a transitional zone between major powers to the north and south. While early periods lack direct inscriptions within the district itself, literary references, archaeological finds, and comparative evidence from adjacent territories allow for a general outline of successive rule.

There has been some speculation regarding a connection between Nanded and the Nanda dynasty of Magadha, who preceded the Mauryas in the 4th century BCE. A line in the Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela (Udayagiri, Odisha), referring to a Nanda king’s activities in Kalinga (eastern India), has led some to suggest that the Nandas may have exercised influence further south than is otherwise documented. The name “Nanded,” occasionally identified with Nau Nand Dehra or “abode of the Nine Nandas,” has been drawn into this conjecture, although this still remains speculative.

In the 3rd century BCE, the region likely fell under the expanding influence of the Mauryas. No edicts of Ashoka have been found within the boundaries of the district, but an inscription issued by a Dharmamahamatra has been discovered at Devtek in present-day Chandrapur. Given the administrative extent of the Mauryan state in Vidarbha and many parts of present-day Maharashtra, it is probable that the territory of modern Nanded was at least nominally included in its domain.

Traces of the Satavahanas at Shiur

With the decline of Mauryan authority, the Satavahanas emerged as the principal power across much of the Deccan. Their capital at Pratishthana (present-day Paithan, Sambhaji Nagar) placed them in close proximity to Nanded and archaeological finds in the district suggest its inclusion within the Satavahana domain.

One of the few sites in Nanded yielding material from this period is situated at Shiur, a village in Hadgaon taluka. Excavations carried out under the supervision of scholars from Deccan College and Solapur University brought to light a modest settlement, tentatively dated to the 1st–3rd centuries CE. The remains consisted chiefly of wattle-and-daub domestic structures, hearths, coarse pottery, and food refuse, including grains such as wheat, barley, rice, and oilseeds, as well as animal bones. A limited number of Satavahana coins were also recovered.

The character of the site, as noted by the excavators, differs markedly from that of the larger Satavahana centres at Paithan, Ter, and Junnar, which are generally associated with state functions or elite activity. Shiur, by contrast, is interpreted as a modest rural settlement. The architectural remains—constructed in wattle and daub, with indications of thatched roofing—together with the absence of luxury items, have been taken to suggest a community of limited material means.

At the same time, the discovery of terracotta beads, shell bangles, and small ornaments fashioned from semi-precious stones such as agate and carnelian has led archaeologists to suggest that the settlement maintained some degree of contact with external trade networks. These materials are believed to have originated from Gujarat and the Saurashtra coast, indicating the presence of long-distance exchange.

Shiur Caves & the Vishnukundins

In the period following the decline of Satavahana authority, the Vakatakas rose to prominence in the Deccan, with the Vatsagulma branch exercising control over much of eastern Maharashtra from the 3rd century CE onward. Their presence is well attested in nearby districts such as Washim and Sambhaji Nagar. It is likely that the region fell within their wider zone of influence during this period. The decline of Vakataka power in the early 6th century appears to have created conditions for the expansion of the Vishnukundins, a dynasty based in the eastern Deccan.

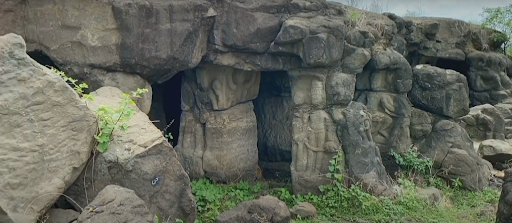

Architectural evidence from this later period is found in the group of rock-cut caves at Shiur, situated on the right bank of the Penganga River in Hadgaon taluka. These caves, carved into a low rock face, are noted for their simple, functional layout. Unlike the more elaborate cave complexes of western India, the Shiur caves feature restrained ornamentation, with carving largely confined to the surfaces of pillars rather than walls.

This treatment has drawn comparison from scholars to cave sites in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, where similar features are found. On stylistic and contextual grounds, archaeologist Vaishali Welankar (2015) has suggested that the caves were excavated in the period following the decline of the Vakatakas, during which time the region is thought to have come under the influence of the Vishnukundins, a dynasty based in present-day Andhra Pradesh.

Following the decline of the Vishnukundins, the Kalachuris of Mahismati and subsequently the Chalukyas of Badami asserted their control over portions of the Deccan. The Kalachuris, though more prominent in central India, appear to have exercised temporary authority in the eastern Deccan during the late 6th century.

The Chalukyas of Badami, under Pulakeshin II, are recorded to have campaigned across the northern Deccan and are said to have incorporated the ancient region of Asmaka, with which Nanded is believed to have been part of.

Rashtrakutas and their Capital at Kandhar

In the centuries that followed, the Rashtrakutas emerged as one of the most powerful dynasties of the early medieval Deccan, with a dominion that eventually encompassed much of the region. The clearest association between the Rashtrakutas and the district is found at Kandhar, located in its southern reaches. Situated along the banks of the Manyad River, the town developed into a regional administrative and military centre by the 10th century CE. Its significance is particularly noted during the reign of Krishna III (c. 939–967 CE), one of the last notable rulers of the dynasty.

In 1959, a broken stone inscription was recovered from an old well near Kandhar. Though partially damaged, it refers to Krishna III and his activities in the town, then called Kandharpura. The king is described in the record as Kandharpuravaradhishwara—“Lord of Kandharpura.” Other names for the site, such as Krishna Kandhara and Krishnadurga, appear in literary and epigraphic sources, further underscoring its status during this period.

Kandhar Fort, now partly in ruins, is believed to have taken its original form under Rashtrakuta rule. Among its more unusual features is a large water reservoir known as Jagattung Samudra, constructed to support the fort complex. The scale of this reservoir is notable, as such hydraulic works are rare in the context of early fort construction in Maharashtra.

Among the more remarkable features of the fort is a 60-foot stone figure of a yaksha, believed to date from the Rashtrakuta period. Carved within the fort premises, the sculpture is notable both for its scale and for its connection to early Deccan artistic traditions. Its presence indicates that Kandhar served not only as a military post but also likely held some cultural or religious significance within the Rashtrakuta sphere.

Following the Rashtrakutas, Kandhar Fort continued to serve as a key regional stronghold. Over the centuries, it came under the control of several ruling houses such as the Yadavas of Devgiri (late 12th to early 14th centuries), the Delhi Sultanate (14th century), the Bahmani Sultanate (15th century), the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar (late 15th to early 17th centuries), and eventually the Nizams of Hyderabad, who ruled the region until the mid-20th century.

Chalukyas of Kalyani and the Hottal Inscriptions

Around the late 10th and 11th century, the Chalukyas of Kalyani rose to prominence in the western Deccan. With their capital at Kalyani (present-day Basavakalyan in Karnataka), it appears that they expanded their territory into parts of what is now Nanded district too. Their presence is recorded at Hottal, a village in Degloor taluka near the Karnataka border.

Hottal preserves several epigraphic records from the Chalukya period, one of which is dated to the reign of Somesvara II (1068–1076 CE). This inscription makes mention of an ashram dedicated to the Rishi Agastya, located along the banks of the Vanjara River, and records grants of land made in support of religious activity there.

The principal Mandir at the site is the Siddheshwar Mandir, built in the Hemadpanthi style using local basalt. The shrine, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiva, is assigned to the 12th century and is noted for its well-proportioned design and finely carved surfaces. Smaller shrines to Nandi and Parashurama stand nearby. The complex has since been designated a protected monument by the state archaeological authorities.

The Yadavas of Devagiri and Mahurgad

By the late 12th century, Nanded district came under the rule of the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, a dynasty that rose to prominence in western Maharashtra and parts of the Deccan. Their capital at Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad, Sambhaji Nagar) served as the administrative centre from which they extended authority across much of present-day Maharashtra, including the Nanded region.

The Renuka Devi Mandir at Mahur, while older in tradition, is believed to have been rebuilt or renovated during the Yadava period. The Yadavas are further associated with the maintenance and development of regional forts, such as Mahurgad, which by this time is said to have become a significant military outpost.

In the centuries that followed, Mahurgad passed into the hands of the Gond rulers, who rose to prominence across Berar and eastern Maharashtra. Under their administration, Mahurgad was organised as a sarkar, or district-level unit, and retained its importance as a local seat of governance. Though the fort itself predates their occupation, it was during their rule that its role as a political and military centre seems to have been most fully developed.

One of the notable Gond-era administrators of the fort was Appasaheb Deshmukh, who served as sardar (military commander) under the Gond king. He is remembered in local accounts for his administration of the fort and for overseeing the affairs of the Mandir. His family remained influential in the area for generations. The fort itself rose to even greater prominence in the later periods, as outlined further below.

Medieval Period

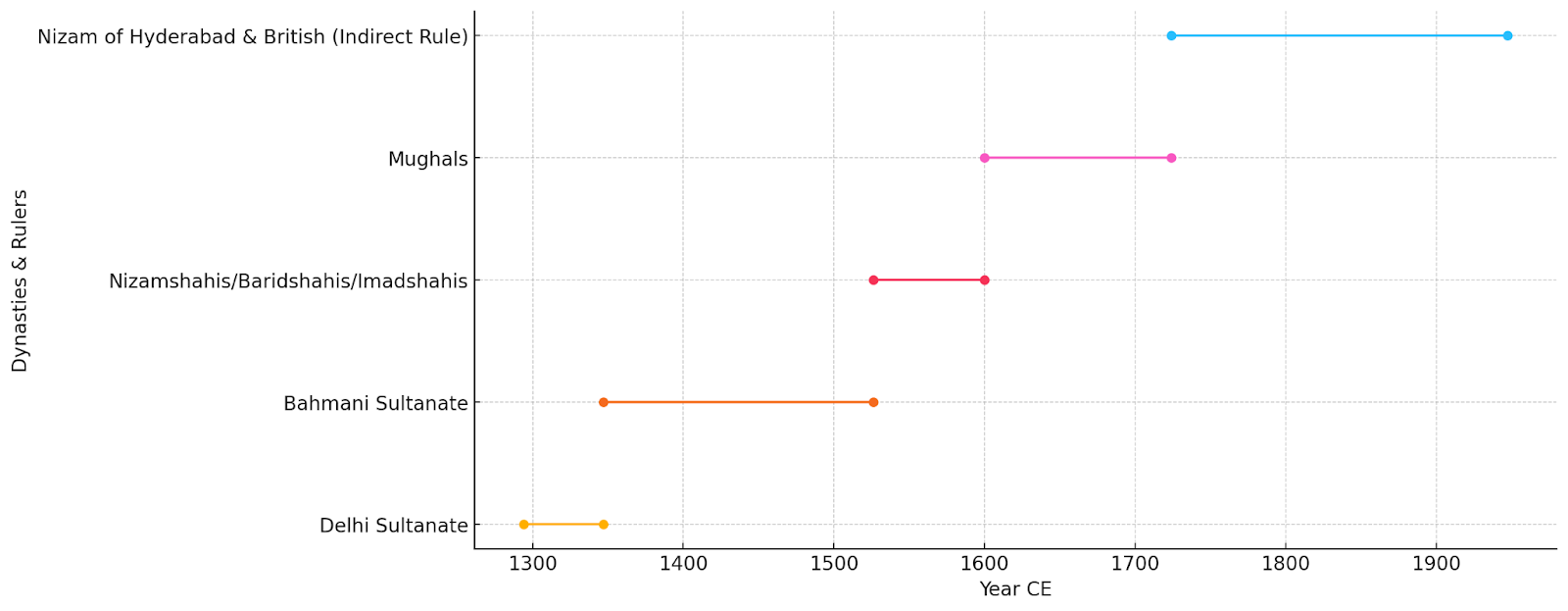

During the medieval period, the territory now comprising Nanded district underwent a series of political transitions shaped by the larger movements of power in the Deccan. From the late 13th century onward, control passed from the Delhi Sultanate to various Deccan Sultanates, the Mughals, and finally the Nizam of Hyderabad. The district remained a zone of military activity and administrative significance throughout this period.

Delhi Sultanate & the Nanded Fort

The first known intervention by the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan occurred in 1294 CE, when Alauddin Khilji, then governor of Kara, raided Devagiri, capital of the Yadava kingdom. This campaign marked the beginning of sustained northern intrusion into the region. Further expeditions followed in 1306, 1308, and 1310 CE, weakening the Yadava state, which collapsed definitively by 1317 CE.

Nanded appears to have come under Sultanate control by 1318 CE, during the early reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq. Around 1327 CE, he is believed to have commissioned the fort at Nanded, situated on the left bank of the Godavari River. The fort formed part of a wider line of defensive posts aimed at securing movement between Burhanpur (Madhya Pradesh) and Daulatabad (Sambhaji Nagar).

Bahmani Sultanate and the Rise of Mahur

With the decline of the Delhi Sultanate in the early 14th century CE, the Deccan witnessed the emergence of new independent regional kingdoms. Foremost among these was the Bahmani Sultanate, established in 1347 CE, which introduced a centralized form of administration across its dominions. The region now comprising the Nanded district was, during this period, subsumed within the province of Berar.

Under the rule of Sultan Muhammad Shah III, the province of Berar was divided into eight territorial subdivisions or tarafs, an administrative innovation that sought to bring greater coherence to regional governance. Of these, Mahur was appointed as the headquarters of one taraf, serving as both a military outpost and an administrative centre. The reorganization was carried out under the guidance of Mahmud Gawan, the Sultan’s distinguished prime minister, who played a central role in shaping the Sultanate’s provincial system.

Berar, as a frontier province, was entrusted to the command of Fatehullah Imad-ul-Mulk, with Mahur designated as his seat of administration. At this time, the northern portion of present-day Nanded District, including parts of the Godavari valley, was incorporated into the Mahur taraf. The command at Mahur was held by Khudawand Khan, an African officer of considerable repute, who established his headquarters within the vicinity.

The town of Nanded, though peripheral to the main centres of power, saw modest expansion under Mahmud Gawan’s tenure. Interestingly, it was during this period that the suburb of Vazirabad was laid out, presumably named in honour of Gawan’s office as Wazir.

By the late 15th century, the Bahmani Sultanate began to fragment under the strain of internal dissent and provincial ambition. As central authority weakened, regional governors assumed greater autonomy. One of the most prominent among them was Kasim Barid, a former courtier who gradually consolidated power in Bidar. In 1490 CE, he formally broke from the Bahmani court and took possession of Kandhar (in present-day Nanded district) and Ausa (in present-day Latur), securing them as his jagir. This marked the beginning of Barid Shahi influence in the region.

In 1500 CE, Mahmud Shah Bahmani attempted to reassert central control over these territories. He summoned Fatehullah Imad-ul-Mulk and Khudawand Khan—both once associated with Mahur—to aid in restoring order. Their refusal to act led the Sultan to dispatch an expedition under Ali Adil Shah of Bijapur. The campaign failed, and authority over Mahur and Kandhar remained fragmented, characterized by shifting allegiances and intermittent military engagement.

During the mid-16th century, the power struggle in the region intensified with the involvement of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. In 1561 CE, Burhan Imad Shah of Berar, with the support of the noble Tufal Khan, launched an expedition against Mahur and Kandhar. The campaign was initially successful, aided by the defection of several local chieftains. However, control proved short-lived. Murtaza Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar soon intervened, pushing into the contested territories to reassert Ahmadnagar’s dominance.

Following the final dissolution of the Bahmani Sultanate in the early 16th century, Mahur was incorporated into the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and still retained much significance. Under their governance, Mahur continued to be assigned as a jagir (a revenue and military estate) granted to loyal nobles.

Guru Nanak Dev at Nanded

During this period of transition, Nanded was a modest town under Ahmadnagar rule, located along a key river route between Berar and the southern plateau. It was during his second udasi (spiritual journey) that Guru Nanak visited the area, travelling from central India through the Narmada valley.

His presence in Nanded is remembered through several gurudwaras, including Sri Nanaksar Sahib, Nanakpuri Sahib, and Mal Tekdi Sahib, which mark sites traditionally associated with his visit.

Though brief, it marked the beginning of Nanded’s long-standing association with Sikh tradition — one that would take on greater importance two centuries later.

Raje Udaram and the Mahur Jagir

By the closing years of the 16th century, the jagir of Mahur was conferred upon Raje Udaram, a Deshastha Rigvedi Brahmin from Washim. Udaram had entered service under the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, where he rose to prominence alongside Lakhuji Jadhavrao, a Maratha sardar of considerable influence. Their skill in light cavalry and mobile infantry operations made them valuable to competing powers in the Deccan. In 1616, amid shifting allegiances and ongoing conflict between the Mughals and the Deccan Sultanates, Udaram and Lakhuji defected from Malik Ambar’s Nizamshahi camp and entered Mughal service.

Udaram’s tenure under the Mughals was brief. He died in 1632 near Daulatabad Fort during a military campaign. Control of Mahur then passed to his wife, Pandita Savitribai, who assumed charge of the jagir and notably came to be known by the title Rai Bagan. Notably, her assumption of authority marks one of the few recorded instances of female jagirdari in the Mughal Deccan (see section: Rai Bagan and the Defence of Mahur for more).

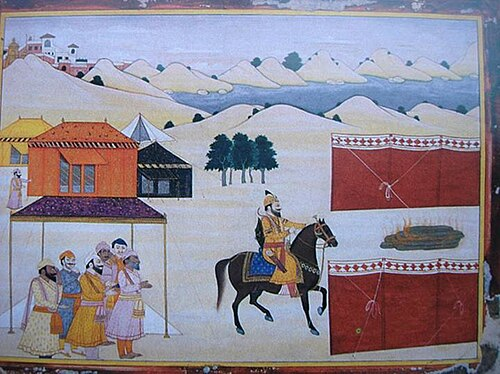

Prince Khurram at Mahur

It is noteworthy that during Udaram’s time, as Mughal control extended further into the Deccan, Mahur appears to have begun to appear in wider conflicts beyond local administration. Around 1622, Emperor Shah Jahan, during his days as a Prince, rose in rebellion against his father, Emperor Jahangir. In the course of this campaign, it is noted in the district Gazetteer (1971) that he took refuge at Mahur before fleeing to Golconda.

Although brief, this episode suggests that Mahur was considered a defensible stronghold with access to interior routes of Berar and support from local Sardars, such as Raje Udaram and his allies. It reflects the growing role of Deccan strongholds in Mughal succession struggles and military planning.

Famine of 1629–30

These years also witnessed severe environmental distress. A devastating famine between 1629 and 1630 affected much of the Deccan, including Nanded district. Widespread crop failure, acute food shortages, and population displacement were reported. The crisis overlapped with military deployments, compounding the strain on supplies.

Rai Bagan and the Defence of Mahur

After Udaram’s death in 1632, as mentioned above, his wife Pandita Savitribai (Rai Bagan) assumed the jagir of Mahur. A woman of considerable administrative ability and martial resolve, she assumed control of the estate during a period of increasing unrest and continued to serve under the Mughal administration.

After the death of her son, Jagjivanrao, the management of the jagir was undertaken jointly by Rai Bagan and her grandson, Baburao. Her leadership is documented in several episodes, notably in the suppression of local uprisings and during campaigns tied to the Mughal succession.

One of the most notable episodes in Pandita Savitribai’s career was her campaign against the local rebel leader, Sardar Herchandrai. In 1658, during the Mughal War of Succession, Aurangzeb—then engaged in consolidating his claim to the throne—entrusted her with the task of suppressing the uprising in the Mahur region. Leading forces drawn from her jagir, Savitribai marched from Mahur to confront the rebellion. Tradition holds that, before battle, she tied her choli to the flagpole in an act of symbolic defiance and rallying, inspiring her troops. Her leadership and personal combat skills contributed directly to the defeat of the rebel forces and in recognition of her service, Aurangzeb formally conferred upon her the title Rai Bagan (which means Royal Tigress).

Savitribai’s involvement in military affairs extended beyond local conflicts. In 1661, she accompanied the Mughal general Kartalab Khan (also known as Murshid Quli Khan) on a campaign to check Shivaji’s growing influence in the Konkan region. The expedition, comprising a force of approximately 30,000 troops, advanced into the rugged forested terrain of Umberkhind with the aim of launching a surprise assault. On 3 February 1661, however, the Mughal army was ambushed in a narrow mountain pass by Shivaji’s forces in what came to be known as the Battle of Umberkhind. The engagement ended in a decisive defeat for the Mughals and demonstrated the effectiveness of Maratha guerrilla tactics. During the campaign, Rai Bagan is said to have advised Kartalab Khan to seek terms with Shivaji, recognizing both the tactical disadvantage and the limitations of conventional warfare in the terrain.

Her presence in such Mughal campaigns, and her management of the estate during successive periods of unrest, ensured the continuity of the Mahur jagir within the family. After her tenure, the estate passed to her descendants, who continued to hold the title Raje Udaram Deshmukh under both Mughal and Nizam authority.

By the early nineteenth century, the jagir had been divided among six branches of the family, each maintaining claims to portions of the estate. While political conditions and administrative reforms would later curtail their autonomy, the family's historical association with Mahur endured well into the colonial period.

Administrative Importance Under the Mughals

By the 17th century, the administrative structure of the Mughal-controlled Deccan had become well defined. The region was then divided into six subahs, namely Berar, Khandesh, Aurangabad, Bidar, Bijapur, and Hyderabad, each under the supervision of a provincial governor reporting to the Viceroy of the Deccan. The territory now forming the present-day Nanded District was split between two such jurisdictions: the sarkar of Mahur, which fell under Berar Subah, and the sarkar of Nanded, assigned to Bidar Subah.

The administrative particulars of this arrangement are preserved in contemporary Mughal sources, notably the Savaneh-e-Dakkan and the Dastur-al-Amal of Emperor Aurangzeb. According to these records, Mahur comprised 20 talukas and 1,141 villages, while Nanded included 30 talukas and 949 villages. It is important to note that these divisions not only reflected geographical extent but also administrative and revenue importance. Six-month revenue assessments placed Mahur at ₹8,17,113 and Nanded at ₹20,68,193, highlighting the region’s substantial agrarian output and strategic role in sustaining Mughal campaigns in the Deccan during the time.

Maratha–Mughal Conflict and Nanded’s Strategic Role

In the later decades of the 17th century, Nanded became a transit zone amid the Mughal campaigns in the Deccan. Its geographical position, lying between the Godavari basin and the northern access routes to Telangana and Berar, rendered it an important transit zone for military operations.

In 1683, as part of Emperor Aurangzeb’s long campaign to subdue the Marathas, Mughal commanders Prince Mu‘izz-ud-Din and Bahadur Khan passed through Nanded on their march from Ramai (Telangana) to Aurangabad (now Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, Maharashtra).

Though the surrounding countryside witnessed intermittent clashes between Mughal and Maratha forces, the forts at Mahur and Nanded remained in Mughal hands for much of this period. The Maratha presence in the district was limited to raiding parties and irregular incursions rather than territorial control.

By 1703, conflict had intensified. Zulfikar Khan, one of Aurangzeb’s principal generals, launched an expedition to dislodge Maratha forces concentrated along the Banganga River in Nanded district. The engagement, though fierce, proved inconclusive. The Marathas, making use of night manoeuvres and guerrilla tactics, withdrew before they could be decisively defeated.

Later, Zulfikar Khan withdrew to Biloli (present-day Nanded district) and made preparations to intercept Maratha forces advancing toward Nanded. He was soon reinforced by Gajiuddin Firoz Jang, then recently appointed Subhedar of Berar, who was also charged with the defence of Telangana. Joint operations were undertaken to stabilise the frontier and to reassert Mughal control over the area. Despite these efforts, Maratha incursions continued with increased frequency. Large portions of Berar were laid waste, and local administration struggled to maintain order.

Guru Gobind Singh and the Story Behind Hazur Sahib

In the year 1707, Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth and last of the Sikh Gurus in human form, arrived in Nanded during the final phase of Aurangzeb’s reign. Guru Gobind Singh made a monumental contribution by formalising the Sikh faith and establishing the Khalsa Panth. He was born Gobind Rai in 1666 in Patna, Bihar, and was the son of the ninth Guru, Tegh Bahadur.

His presence here marked a significant episode in both regional and Sikh history. Contemporary accounts and later Sikh tradition suggest that the Guru intended to explore the possibility of an alliance with the Marathas, who, like the Sikhs, were engaged in resistance to Mughal authority. His primary karmabhoomi was in Anandpur Sahib, Punjab, where he led his followers as a warrior, poet, and philosopher. He is the one who institutionalised the Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh holy scripture) as the eternal and final Guru.

His last days were spent in Nanded, Maharashtra, where he established his camp on the banks of the Godavari River. His time in the town, however, was cut short. Some months after his arrival, he succumbed to injuries sustained during an earlier attempt on his life. He died in October 1708, and with his passing, the line of living Sikh Gurus came to an end. Before his death, he is said to have invested the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy scripture of the Sikhs, with the role of eternal spiritual guide.

A modest memorial was erected at the site of his cremation, which later became the location of the Takhat Sachkhand Shri Hazur Abchalnagar Sahib. The present structure was commissioned by Maharaja Ranjit Singh and constructed between 1832 and 1837. Situated in the centre of Nanded town, Hazur Sahib is today recognised as one of the five Takhts of Sikhism and remains the most important centre of Sikh pilgrimage.

Decline of Mughal Power and Rise of the Nizam

The first years of the 18th century witnessed a noticeable weakening of Mughal authority in the Deccan. In the years immediately following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, Mughal administration in the Deccan began to show visible signs of strain. Among many other factors, the uncertainty created by the rivalry among his sons for succession further weakened the central authority’s hold over outlying territories.

In the district of Nanded, administrative control during this period was held by Amin Khan Deccani, a figure of some repute, whose father had served in the Mughal campaigns against the Marathas. The jurisdiction assigned to Amin Khan extended over forty-four mahals, comprising a broad tract of territory that included portions of what are now Nanded, Adilabad (Telangana), and Nizamabad (Telangana) districts.

Tensions between the Mughal-appointed officers and local landholding families, particularly those aligned with Maratha interests, were frequent. Among the most notable of these was Mandhata, son of Kanhoji Sirkiya, whose refusal to submit to imperial authority necessitated a series of punitive actions.

In 1714, the office of Viceroy of the Deccan was conferred upon Asaf Jah I, known also as Nizam-ul-Mulk, who was at that time among the more capable nobles in the service of the Mughal court. His tenure, however, was soon complicated by courtly intrigues and administrative rivalries, most notably with Mubariz Khan, governor of the Hyderabad Subah, who refused to recognise Asaf Jah’s superior position.

This rivalry culminated in a decisive engagement at Shakar Kheda, in 1724, situated in the present-day Buldhana District. The battle ended in the defeat and death of Mubariz Khan, after which Asaf Jah ceased to act under direction from the Mughal centre. Though he retained nominal allegiance to the Mughal emperor, his administration henceforth operated independently.

With this development, the district of Nanded now passed from Mughal oversight into the sovereignty of the Nizam, under whose successors it would remain for the next two centuries.

Maratha–Nizam Rivalry and Local Engagements

The second half of the 18th century witnessed renewed military activity in the Deccan, as the authority of the Hyderabad State under the Nizams came increasingly into contest with the expanding influence of the Maratha Confederacy.

The region now comprising Nanded district, though formally under Nizam control, lay along a shifting frontier and was frequently entered by Maratha forces seeking the enforcement of revenue claims, chiefly in the form of chauth and sardeshmukhi.

The earliest recorded encounter of note in the area occurred in 1760, when Gopal Singh, a local jagirdar of Kandhar, was killed in the Battle of Udgir while serving in the Nizam’s forces. It is noteworthy that the Gopal Singh along with the Ajayacand family were known to have held jagirs in Kandhar, Mahur, and nearby talukas, and played a role in the local defence system by maintaining forts, raising contingents, and supplying provisions to Hyderabad’s military expeditions during this time. Architectural remains such as the Gardikhanch Havelis are associated with their tenure.

Maratha activity continued into the closing years of the century. In 1790, Raghunathrao Bhosale led a mobile force into the district and collected tribute from several villages and talukas. In response, the Nizam’s administration appointed Hifzullah Khan as subhedar of Mahur, and troop detachments were issued under Jamil Beg Khan and Iradat Khan, who operated from Nanded and Biloli. Several engagements occurred in the vicinity, though the Maratha forces, relying on light cavalry, typically avoided prolonged confrontation.

While local conflicts persisted, the broader political alignment of the period was also shifting. By the end of the century, the Nizams had entered into formal alliance with the British, further complicating relations with the Marathas, who were themselves in recurrent conflict with the East India Company. The power of the Maratha Confederacy declined in the years following, and by the early nineteenth century, the Nizam's position in the Deccan had solidified.

Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountcy

By the late 18th century, the Nizam of Hyderabad had entered into formal alliance with the British. In 1798, amid growing pressure from internal rivals and external threats, Asaf Jah II entered into the Subsidiary Alliance with the East India Company. While this preserved the nominal sovereignty of Hyderabad, it placed the responsibility for external affairs and military defence in the hands of British officers stationed within the Nizam’s dominions. With this arrangement, Hyderabad became the first princely state to fall under British protection, setting a precedent for others.

Over the following decades, the Nizams of Hyderabad proved to be a steady ally to the East India Company. It supported British efforts during the Anglo-Mysore and Maratha Wars, and by the mid-19th century, Nanded and its surrounding areas came firmly within the orbit of British-influenced Hyderabad.

The Hatkars and the Rebellion of 1819

It was within this new dispensation that a prolonged episode of unrest emerged in Nanded. Among the hill country of Hadgaon and Kinwat, a section of the Hatkar community, a martial and pastoralist group who have long resided in the upland tracts of eastern Berar and the adjoining talukas of Nanded, rose in open defiance of Hyderabad’s authority.

The movement gathered strength under the leadership of Nowsaji Naik. By 1810, he had succeeded in establishing a network of strongholds across the uplands, most notably the fort of Nowah in Hadgaon taluka. The causes of this rebellion appear to have stemmed from local grievances, most likely related to revenue impositions, land disputes, and long-standing tensions between regional zamindars and representatives of the Hyderabad government.

For nearly ten years, the Hatkars maintained their resistance against the Nizam’s administration. Their efforts, however, came under mounting pressure as the Hyderabad government—now closely aligned with the British—decided to put an end to the uprising. Early in January 1819, combined forces of the Nizam’s army, British officers, and Arab mercenaries began a siege of Nowah Fort, the central stronghold of the rebellion in Hadgaon taluka of present-day Nanded district. The operation, as noted in the district Gazetteer (1971), commenced on 8 January and continued for over three weeks. The fort was eventually taken on 31 January 1819, bringing the main phase of the insurrection to a close. The siege was conducted with considerable force and resulted in significant casualties on both sides.

The First War of Independence, 1857

In the years that followed, resistance to outside control took on new forms. During the disturbances of 1857, although the Nizam himself remained aligned with the British, scattered signs of disaffection emerged in parts of Nanded district. Local contingents, particularly among the Rohillas, engaged in open confrontation, and several jagirdars were found to have extended support to the rebels.

One such figure was Narayan Barjara, who was tried and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment in the Mir Adalat (district court) of Nanded. Further south, the Jagirdar of Kovlas, Raja Deep Singh, came under scrutiny for correspondence with agents of Nana Saheb. These instances, though limited in scale, pointed to the underlying tensions between traditional elites and the expanding machinery of imperial control.

Hyderabad Samajik Sudhar Sangh

In the early 20th century, Nanded became a notable centre for social reform within the Hyderabad State. In 1915, the Hyderabad Samajik Sudhar Sangh (Hyderabad Social Reform League) was established under the leadership of Sri Keshav Rao Koratkar and Sri Waman Naik. The organisation’s conferences took up a range of social questions, including women’s education, widow remarriage, and the establishment of libraries.

Notably, out of the six major conferences organised by the League, three were hosted in Nanded. The inaugural social conference occurred in Kavanah within the Nanded district in 1918, chaired by Sri Sadanand Maharaj. The second conference took place in Hadgaon in the Nanded district in 1919, led by Sri Keshav Rao Koratkar. The third conference convened in Nanded the subsequent year, presided over by Sri Waman Naik.

Post-Independence Era

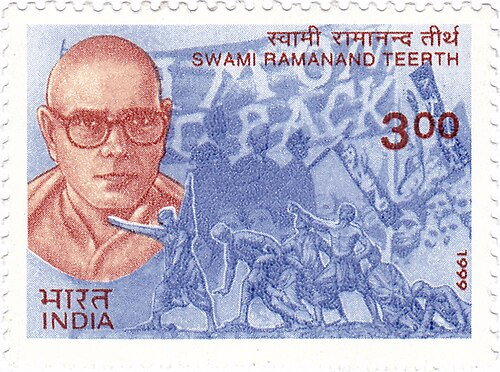

At the time of India’s independence in 1947, Nanded formed part of the princely state of Hyderabad under the rule of the Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan. While the majority of the population favoured joining the Indian Union, the Nizam was reluctant to accede, seeking to preserve Hyderabad’s independence. This created a political deadlock that was further complicated by rising communal tensions across the state.

In September 1948, after negotiations failed and internal disorder escalated, the Government of India launched Operation Polo, a brief military campaign that brought Hyderabad under central control. The Nizam surrendered on 17 September 1948, and Hyderabad was formally integrated into the Indian Union. In the aftermath, a fact-finding committee led by Pandit Sunderlal recorded serious communal violence in several parts of the former state, identifying Nanded among the worst affected districts.

The integration of the region is commemorated annually on 17 September as Marathwada Muktisangram Din in Maharashtra. The political mobilisation leading up to Hyderabad’s merger with India was supported by local leaders, such as Swami Ramanand Teerth, with Hadgaon in Nanded district serving as a prominent centre of the movement.

Following its integration, Nanded became part of Hyderabad State under the Indian Union. This arrangement continued until the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which reorganised state boundaries based on linguistic demographics. As a predominantly Marathi-speaking region, Nanded was transferred to Bombay State, and in 1960, it became part of the newly formed state of Maharashtra, where it remains to this day.

Sources

Amit Samant Fort. 2017. Kandhar Fort & Siddheshwar Mandir, Hottal. Samant Fort Blog.https://samantfort.blogspot.com/2017/11/kand…

B.G. Kunte ed. 1971. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Nanded District. Ist Edition. Government Printing Stationery and Publication, Bombay.

Charles Lewis Tupper. 1893. Our Indian protectorate; an introduction to the study of the relations between the British government and its Indian feudatories. Longmans, Green and co., London and New York.

Devika Rangachari. 2022. The Mauryas: Chandragupta to Ashoka – The Backstories, The Sagas, The Legacies. Simon & Schuster, New Delhi.

G. S. Randhir. 1990. Sikh shrines in India.Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, New Delhi, India.

Google Arts & Culture. n.d. Kandhar: The Seat of Rashtrakutas. Live History India.https://artsandculture.google.com/story/kand…

Govt. of India. 2011. "District Census Hand Book – Nanded" (PDF).Census of India.

Hindu Temples Blog. n.d. Legend & Story of Renuka Devi Temple in Maharashtra. Hindu Temples Blog.https://hindutemplesblog.wordpress.com/legen…

Indian Express. 2012. Archaeologists Restore 11th-Century Temples at Hottal. Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/india/maha…

Lakshmi Subramanium. n.d. Kandhar Fort, Nanded District, Maharashtra. Sahasa.https://sahasa.in/2021/06/02/kandhar-fort-ka…

Lt. Col. Sir Wolseley Haig. 1971. The Cambridge History of India. Vol. 4. S. Chand & Co., New Delhi.

Navjeeven Gopal. 2018. Explained: The role of the 5 Sikh takhts, and the debate over a proposal for a 6th.https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/…

Neha Madaan. 2012. 'Common men during Satavahana rule were poor. 'The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Outlook Traveller. 2017. Nanded: A Historical City. Outlook India.https://www.outlookindia.com/traveller/ot-ge…

Pramod Chaudhary. 2020. Nandagiri Fort Has History Over Two Thousand Years.eSakal.https://www.esakal.com/marathwada/nandagiri-…

S. Harpal Singh. 2019. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/telan…

The Temple Guru. n.d. Kaleshwar Temple, Nanded. The Temple Guru.https://thetempleguru.com/listing/kaleshwar-…

TravelSetu. n.d. Hottal Siddheshwar Temple. TravelSetu.https://travelsetu.com/guide/hottal-siddhesh…

Utsav. n.d. Nanded Hottal Festival. Utsav.https://utsav.gov.in/view-event/nanded-hotta…

Vaishali Welankar. 2015. Chronology of The Brahmanical Caves at Shiur.Presented at 2nd Annual Archaeology of Maharashtra International Conference, 14th & 15th January, 2015.https://www.academia.edu/69293681/Chronology…

Wikipedia Contributors. n.d. Hadgaon. Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadgaon

Wikipedia Contributors. n.d. Nanded District. Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanded_district

Wikipedia Contributors. n.d. मराठवाडा मुक्तिसंग्राम दिन. Wikipedia.https://mr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E0%A4%AE%E0%A…

William Hunter et al. eds. 1908. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India. Vol. 13. The Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.