Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Early Religious and Epic Significance

- Mangi-Tungi and the Jain Tradition

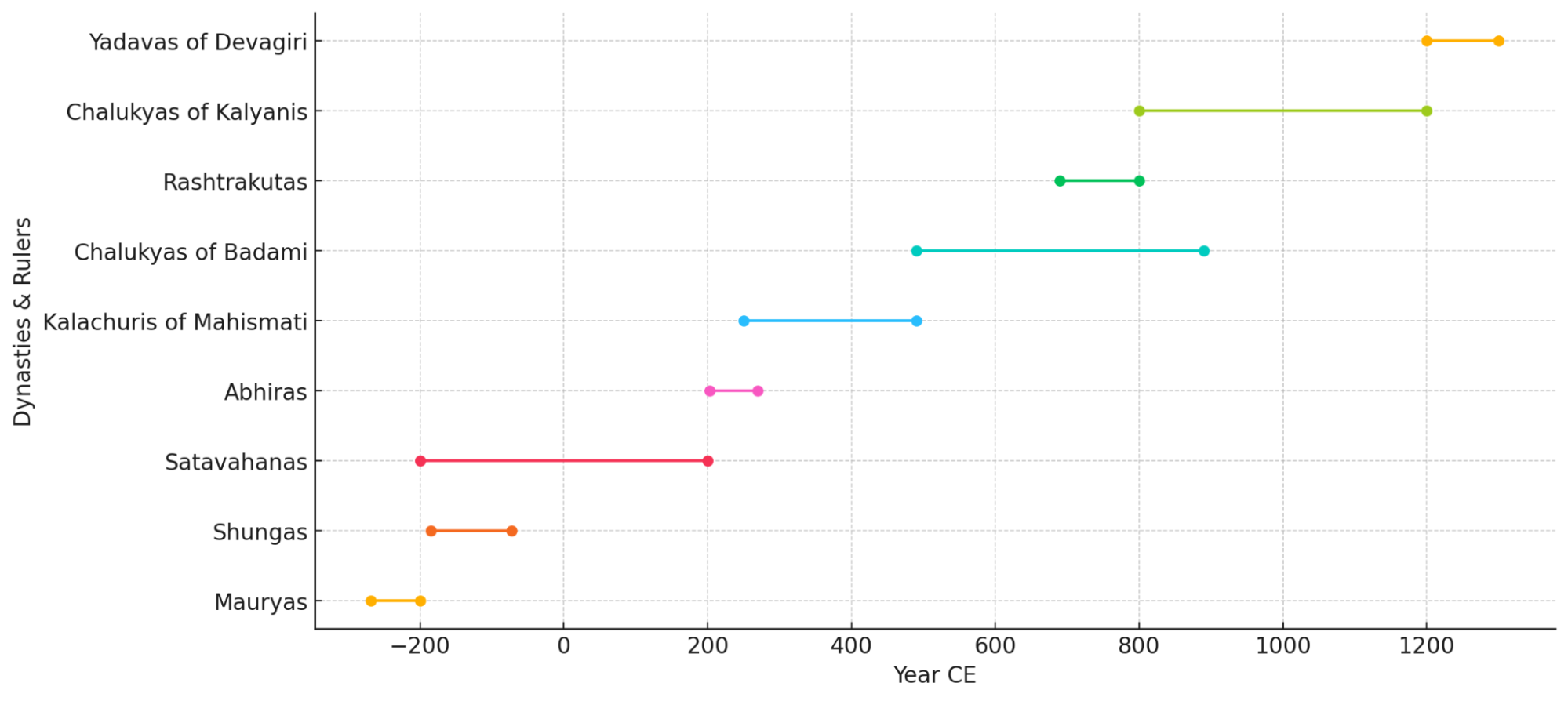

- Early Rulers and Trade Networks (c. 2nd Century BCE Onwards)

- Nashik under the Satavahanas (c. 2nd Century BCE – 3rd Century CE)

- Satavahana Patronage: The Pandavleni Caves and Inscriptions

- The Abhirs and a Period of Transition (c. 3rd Century CE)

- The Rashtrakutas and Continued Patronage (c.7th - 10th Century CE)

- The Yadava Dynasty and Fortification of the Region (c. 9th - 14th Century CE)

- Gondeshwar and Trimbakeshwar Mandirs

- Sant Nivruttinath

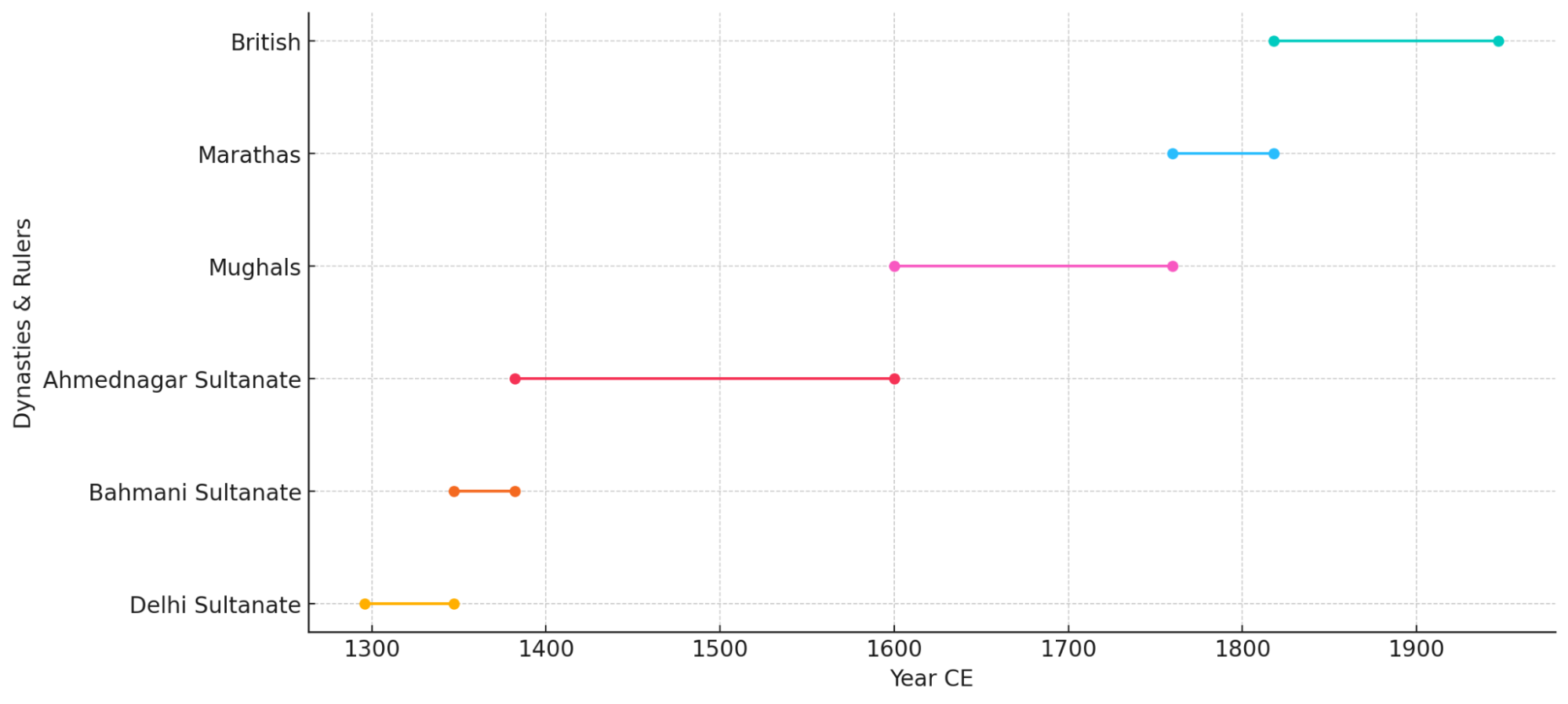

- Medieval Period

- Ramshej Fort

- Bagul Kingdom

- Strategic Significance of Baglan

- Galna Fort

- Dhodap Fort

- Trymbakgad or Brahmagiri Fort

- Jain monuments in Anjaneri

- Nizam Shahi

- Rise of Marathas

- Later Marathas and the British

- Kalaram Mandir

- Colonial Period

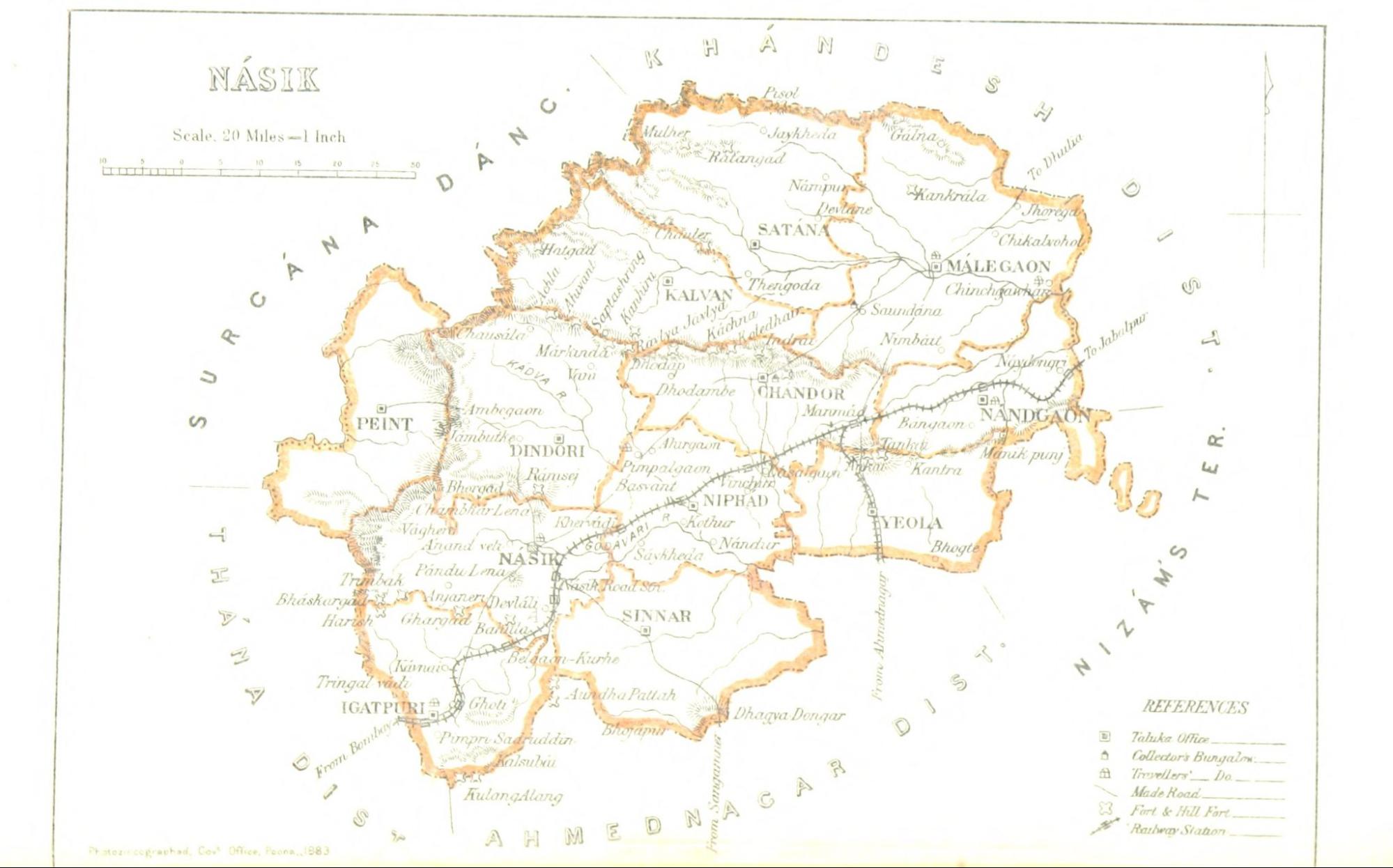

- The Establishment of British Rule and a New District Formation (1818–1869)

- First War of Independence in Nashik (1857)

- Cultural and Civic Developments in Colonial Nashik

- Sarvajanik Vachanalaya

- Nashik News

- Natural Disasters and Urban Development

- The Great Flood of 1872

- Nashik Tram

- Nashik in the Freedom Struggle

- Rise of Revolutionary Societies

- The Nashik Conspiracy Case (1909)

- The Nashik Satyagraha

- Modern Agricultural Identity: Table Grape Revolution of Ojhar (Ozar)

- Sant Janardan Swami

- Post-Independence

- Post-1960: A Hub of Agriculture and Industry

- The Grape Revolution

- Modernization and a Vision for the Future

- Sources

NASHIK

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Nashik district, situated in northwestern Maharashtra along the Godavari River, possesses a rich and layered history. For millennia, it has served as a revered center of pilgrimage, while its strategic location has also made it a coveted seat of power for the great dynasties of the Deccan. The district’s identity is uniquely intertwined with these deep spiritual traditions and its significant political past.

The roots of its spiritual heritage are embedded in the epic Ramayan, and its landscape is marked by ancient sites like the Pandavleni Caves and the Jain center of Mangi-Tungi. This sacred importance is perhaps most famously expressed through the Kumbh Mela, one of the region's most venerable gatherings, which has been hosted here for centuries.

Alongside this spiritual legacy, Nashik's political history is told through its formidable hill forts, which are representative of various dynasties in the region. These structures served as strategic centers for successive rulers, from the Satavahanas to the Marathas. In a more recent era, the district also played a pivotal role in India’s struggle for independence, contributing its own chapter to the nation's fight against colonial rule. The legacy of these spiritual traditions and political conflicts has left an indelible mark on the district, shaping its unique cultural and historical identity.

Etymology

The word Nashik finds its origins in Sanskrit word Nasika, which translates to nose. According to the Ramayan, it was in Panchavati (present Tapovan area in Nashik city), that Lakshman severed the nose of the Surpanakha (Ravan’s sister). In observance of this event and its cultural significance, there stands a Lakshman Mandir in the Tapovan area of Nashik today. Consequently, this act has given rise to the local belief that the city gained its name, Nashik, from this significant episode in the Ramayan. Further, according to Hindu legends, Nashik is identified with different names in various Yugas. During Satya Yuga, it was referred to as Padmanagar, in Treta Yuga as Trikantak, in Dvapara Yuga as Janasthana, and finally, in Kali Yuga, it became Navashikh or Nashik.

It is believed that during the Mughal period, Nashik bore a different name: Gulshanabad. This title attempted to encapsulate the essence of Nashik during that era, evoking images of roses in a timeless cityscape.

The city was named as it is today in the early 19th century when the Marathas gained control over Nashik. Although the Maratha rule was short-lived due to the advent of the British, the name endured.

Ancient Period

Nashik holds deep historical and religious significance. The region is prominently featured in the Ramayan, and its landscape is dotted with archaeological sites that trace the rise and fall of the great dynasties of the Deccan. From its sacred rivers to its rock-cut caves, Nashik's past is a testament to its enduring importance as a spiritual and political center.

Early Religious and Epic Significance

Nashik’s most ancient identity is tied to the epic Ramayan. Panchavati, situated on the left bank of the sacred Godavari River, holds a profound significance as the very spot where the crucial phase of Sri Ram's exile is believed to have unfolded. According to tradition, the entire Aranya Kanda of the epic took place here, weaving Nashik into the fabric of revered Hindu yatri sites.

Nashik’s association with the Kumbh Mela is also rooted in ancient Hindu Puranas, which tell the story of the Samudra Manthan. During a divine struggle for a pot of immortalizing nectar, drops are said to have fallen on Nashik, consecrating it as one of the four sacred sites for the festival.

Alongside its significance in Hindu traditions, ancient Nashik was also a prominent center for Jainism and Buddhism, with numerous sacred sites bearing witness to the deep roots of these faiths in the region.

Mangi-Tungi and the Jain Tradition

A key site illustrating the deep roots of Jainism in the region is Mangi-Tungi, a twin-peaked hill located in present-day Tahrabad village. Revered in Jain tradition as the place bearing the sacred footprints of Rishabhanatha (also known as Adinatha), the first Tirthankara, the site’s sanctity is tied to the earliest phase of Jainism. For centuries, the ancient mandirs and caves atop these hills have served as a significant yatri destination.

The intricate carvings and sculptures found within are tangible expressions of Jain tradition in the region. Although detailed historical records from ancient times may remain elusive, the significance of Mangi Tungi endures as an integral chapter in Jain religious history.

Early Rulers and Trade Networks (c. 2nd Century BCE Onwards)

While Nashik would later fall under the influence of major dynasties, its earliest history was likely shaped by local chieftains. It is important to note that prior to the ascendancy of these larger powers, Nashik was likely governed by local chiefs who were subservient to the great commercial overlords of Tagar and Paithan. Tagar, identified in the 1st-century CE Greco-Roman text The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, was a crucial trading center along the Dakshinapath inland trade route (present-day Ter in Dharashiv district). Similarly, Pratisthana (present-day Paithan in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar) was another vital hub in the region.

According to the Gazetteer (1883), these local rulers held their headquarters at centers like Anjaneri, Saler, and Chandor, all located within the modern Nashik district. Unfortunately, the scarcity of historical sources for this early period makes it challenging to construct a comprehensive narrative of Nashik's history before the arrival of better-documented rulers.

Nashik under the Satavahanas (c. 2nd Century BCE – 3rd Century CE)

Among the ancient dynasties that ruled the Deccan, the Satavahanas stand out prominently, with their influence stretching over the region for an impressive four centuries. As the first major ruling dynasty for which distinct records remain in Nashik, their legacy is richly documented in archaeological remnants that highlight their patronage of the region's cultural and religious life.

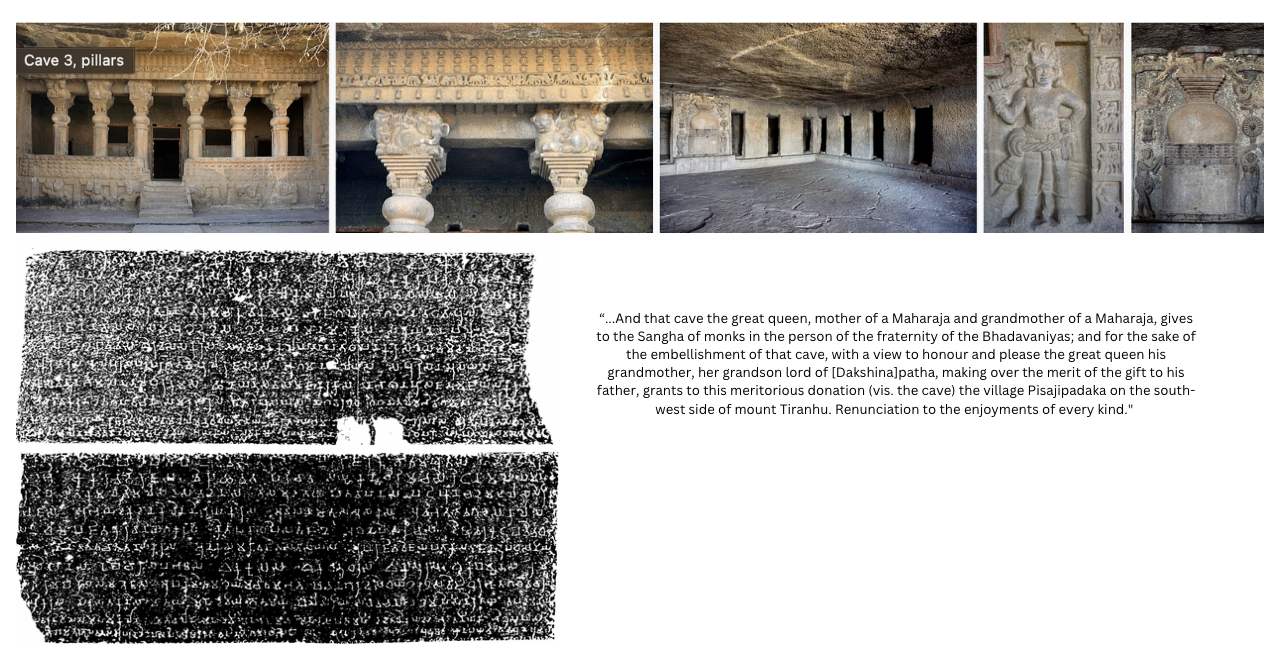

Satavahana Patronage: The Pandavleni Caves and Inscriptions

The most prominent testament to the Satavahana era in Nashik is the Pandavleni Caves, a remarkable collection of 24 rock-cut caves situated on the Trirashmi Hills, approximately 8 km south of the city's center. Originally known as "Pundru" in the Pali language due to their yellow ochre appearance, these caves were carved to serve as residences for Buddhist monks. The modern name, "Pandav Leni," is derived from a local belief that the Pandava brothers of the Mahabharata resided here during their exile.

The construction of these caves and the generous endowments made to support the monks highlight the strong Buddhist influence that pervaded the region. Among the 24 caves, two are of particular interest: the main cave, which contains an impressive Stupa, and Cave No. 10, renowned for its detailed inscriptions. These inscriptions provide invaluable historical insights, shedding light on the rule and patronage of three key dynasties: the Satavahanas, the Western Kshatrapas, and the Abhiras.

These caves stand as a testament to Nashik's deep-rooted archaeological heritage, showcasing diverse religious practices and architectural styles. Cave No. 3, famously known as the Gautamiputra Vihara, is the largest and most impressive in the complex. An inscription confirms it was commissioned by Queen Gotami Balasiri in honor of her son, the great Satavahana king Gautamiputra Satakarni.

Notably, the inscriptions also reveal that patronage extended beyond the Satavahanas. Cave No. 10 is renowned for a detailed inscription by Ushavadata, the son-in-law of the Western Kshatrapa ruler Nahapana. This inscription, dating to the 2nd century CE and notable for being an early use of Sanskrit in the region, records Ushavadata’s significant contributions. He not only funded the excavation of the cave but also donated 3,000 gold coins for the food and clothing of the monks residing there. The inscription further documents his other philanthropic activities, including the donation of a field and the construction of public infrastructure, alongside records of his military campaigns. This shows that Nashik was an important center that attracted patronage from multiple powerful dynasties.

The Abhirs and a Period of Transition (c. 3rd Century CE)

Following the era of Satavahana and Kshatrapa influence, Nashik entered a brief period of transition under the rule of the Abhirs. For a duration of 67 years, the region was governed by the Abhir dynasty under King Ishwarsena Abhira. Although their historical records are often obscure, historians contend that the Abhirs were a migratory group that made their way to India from eastern Iran. This theory is supported by references in the Puranas, which mention Abhirs inhabiting the territory of Herat.

In the Deccan, they were often identified as the Gavali or Gwali community, a name derived from their primary profession as pastoral cowherders. It is also widely argued that they are the ancestors of the contemporary Ahir community, which is now found across various parts of India.

The Rashtrakutas and Continued Patronage (c.7th - 10th Century CE)

Following the Abhir interlude, the Rashtrakuta dynasty rose to become the supreme power in the Deccan by the mid-8th century. The Kalaram Mandir in Nashik stands as a living testament to the city's deep-rooted history during this era.

While its origins are associated with the Rashtrakuta period, the Mandir is most revered for the ancient pratima of Bhagwan Ram that resides within its walls, which local tradition holds to be more than two millennia old. The history of the murti is one of remarkable survival. According to local accounts, the original Mandir faced destruction during a later medieval assault. In a proactive effort to safeguard the ancient pratima, Mandir priests are said to have hidden it in the Godavari River. The Mandir lay in ruins for some time before its eventual reconstruction, ensuring the preservation of this important religious heritage.

The Yadava Dynasty and Fortification of the Region (c. 9th - 14th Century CE)

Under the Yadavas, whose empire extended from Nashik to their capital at Devagiri, the town of Sinnar (in modern Nashik district) emerged as a vital stronghold. The Yadavas were patrons of Mandir architecture and military fortifications, and their reign is marked by the construction of significant religious monuments across the region.

Gondeshwar and Trimbakeshwar Mandirs

The magnificent Gondeshwar Mandir in Sinnar, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiva, was constructed during the 11th or 12th century and is an example of the Hemadpanthi architectural style associated with the Yadavas. Another significant religious center from this era is the Shri Trimbakeshwar Mandir, which houses one of the 12 Jyotirlingas and is revered for its unique three-faced lingam showing Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiv.

Nashik retained its spiritual prominence, with rulers commissioning the construction of different religious monuments over the ages. This spiritual importance is highlighted by an essential aspect of the Yadava dynasty's history in Nashik, which is their religious patronage. Under Yadavas, whose empire extended from Nashik to Devagiri, Sinnar (the present day Sinnar taluka of Nashik district) emerged as a vital stronghold for the dynasty during the period. Within Sinnar, a prominent testament to the Yadava dynasty's significant presence and influence can be witnessed through the magnificent Gondeshwar Mandir. This remarkable Mandir, constructed during either the 11th or the 12th century was dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv. It stands as a compelling embodiment of their legacy in the region.

Gondeshwar Mandir in Nashik stands as a testament to the legacy of the Yadava rulers, showcasing some of the most exceptional examples of surviving Hemadpanthi architecture.

Sant Nivruttinath

Sant Nivruttinath made a foundational contribution to the Warkari tradition as the elder brother and revered Guru of Sant Dnyaneshwar. He was born around 1273 in Apegaon (Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district).

After being initiated into the Nath Yogi tradition by his Guru, Gahaninath, Nivruttinath became the spiritual guide for his younger siblings (Dnyaneshwar, Sopandev, and Muktabai). It was he who instructed Dnyaneshwar to write the Dnyaneshwari. His teachings were a blend of Nath philosophy and Varkari devotion. His primary karmabhoomi was the journey he took with his siblings, but his sacred resting place is in Trimbakeshwar, near Nashik. His Samadhi at Trimbakeshwar is a key pilgrimage site, visited by all Warkaris.

Medieval Period

While ancient records offer valuable insights into Nashik's cultural history from a historical lens, they may provide fewer details to write a comprehensive history of the region. The shifts that occurred during the early medieval era reveal significant insights into the broader Deccan region's historical evolution, including Nashik. One notable aspect that emerges is the pivotal role played by local rulers or ‘chiefs’, even when their power was relatively modest. These local leaders shaped Nashik’s political and military history highlighting their resistance against external incursion. Adding to this it suggests their assertiveness in pursuing independence and adaptability in navigating the complex regional dynamics of their time and interest for territorial expansion as well.

In 1298, Nashik district's history underwent a significant shift with a military invasion spearheaded by Alauddin Khilji of the Khilji dynasty from the North into the Deccan. This occurred during the period when the Yadava dynasty, governed by Raja Ramachandra, held sway over the region. This military campaign served as a crucial turning point, opening the path for Delhi to expand its influence into the Deccan. By 1311, this expansion had progressed to the point where the Delhi Sultanate was able to assimilate the dominion previously held by the Yadavas, solidifying the territory's inclusion within the ever-expanding dominion of the Delhi Sultanate. This event marked a significant moment in the historical narrative of Delhi's growing control and presence in the Deccan.

Nashik witnessed a series of changes in governance over the centuries. From the late 12th century, it was under the administration of Delhi officials stationed in Devgiri (present Daulatabad). Subsequently the rule transitioned to the Bahmani kings. Even though Nashik remained under the jurisdiction of Daulatabad during Bahmani rule, according to the Gazetteer (1883), neither the Bahmanis nor the Delhi Sultanate were able to exercise complete control over the region.

Ramshej Fort

The Ramshej Fort, situated 10 km northwest of Nashik in Maharashtra, is rooted in the ancient Ramayan epic. It is believed that Ram stayed here during his exile.

During Aurangzeb's reign, the Fort, then under Sambhaji's control, became a target for the Mughals as they sought to conquer Nashik. Aurangzeb sent Shahbuddin Gaziudin Firozejung with 40,000 soldiers and artillery to besiege the Fort. Despite the massive Mughal army, Ramshej's commander masterfully held the Fort. To counter, Chhatrapati Sambhaji dispatched Rupaji Bhosale and Manaji More with 7,000 troops, leading to a Maratha triumph.

In their desperation, the Mughals consulted a Tantrik who devised a plan using a mystical golden serpent statue. Yet, as the Mughals approached Ramshej's entrance, they were ambushed by Maratha stone attacks, forcing them to retreat. Even subsequent Mughal attempts, like one by Kasimkhan Kiramani, failed.

Bagul Kingdom

In the history of Nashik district, Baglan (present Baglan Taluka of Nashik district) stands out as a region highly coveted by external powers. Even as the historical period shifted, its importance endured. Baglan including Galna fort, which provides valuable insights into Nashik’s past, shedding light on the region’s socio-political dynamics and historical interactions. As Baglan was an integral part of the broader landscape in which Nashik is situated, its history helps contextualise and understand the historical evolution of Nashik.

A seemingly unremarkable taluka today, Baglan held an interesting history as the Bagul kingdom, likely under the rule of Rathods. Although scarce source material limits the comprehensive exploration of Rathods influence in the region. However, it is evident that for over three centuries, from 1308-1619, the Baglan Kingdom had its roots deeply embedded in the region. The area was not only rich in historical significance but also in its diverse population, which included Malis, Bhils, Marathas etc.

It is likely that the Bagul kingdom had come under the influence of the Bahmanis (1347 to 1527), as evidenced by instances of Maratha resistance against the Bahmanis. During the tumultuous period of the Bahmani-Vijayanagara hostilities, as the Bahmani Sultan had to redirect his forces to confront the Vijayanagara Empire in the Deccan. The Baglan chief, in cooperation with Bahram Khan (the Mughal army’s commander-in-chief), embarked on a daring yet ultimately unsuccessful revolt against the Bahmanis.

Strategic Significance of Baglan

The geographical feature holds a profound significance. In the Baglan area, two primary hill ranges, the Selbari range and the Dholbari range, stretch parallel to each other in an east-west direction. Baglan held great significance since the time of its Rathod rulers, as these ranges served multiple purposes. Initially, they were utilized to oversee the primary ancient commercial route, the Burhanpur-Surat tract, connecting Surat to Daulatabad and Golconda, with the proximity of Burhanpur fostering commerce in the region.

To safeguard and oversee these commercial routes, several hill forts were constructed in the Baglan region by the Rathods, specifically Salher (in present day Salher Village, Satana taluka) and Mulher (in present day Mulher village, Nashik). In later decades, when admiring the splendor and resources of ancient Baglan, the Mughal court historian Abul Fazl, in his ‘Ain-i-Akbari,’ observes that “between Surat and Nandurbar is a mountainous but flourishing tract called Baglana, the chief of which is a Rathor, commanding 3,000 cavalry and 10 infantries. Fine peaches, apples, grapes, pineapples, pomegranates, and oranges grow here. It possesses seven remarkable forts, among which are Mulher and Salher.”

Galna Fort

In close proximity, approximately 35 km away from Baglan, the Galna Fort was under the rule of Maratha chiefs. Positioned strategically, this fort also held great significance along the Burhanpur-Surat trade route. Located amidst the hills that stretch between Malegaon and Dhule, it stands as one of the well-preserved forts in Maharashtra, with its bastions and entrance still in a remarkably good state of repair. Until 15th century, around 1487, the Marathas firmly held sway over the fort.

In 1487, a major shift occurred when two brothers, Malik Wuji and Malik Ashraf (both Governors of Daulatabad) seized control of Galna fort from the Marathas, who at the time ruled under the suzerainty of the Bahamani Sultan. Chronicler Ferishta notes that during this period of political unrest in the Bahamani court, a Maratha chief who had taken possession of Galna was compelled to surrender it to Malik Ashraf.

British historian James Grant Duff similarly records that the Marathas had held Galna as a stronghold until it was recaptured by the Malik brothers around 1487. In the late 15th century, Galna became part of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate through an alliance with Bijapur and Berar. This control was soon contested: Ahmad Nizam Shah subdued the ruler of Galna in 1499, but following the murder of Malik Wagi, local chiefs in the Nashik region seized the opportunity to reassert their independence. Ahmad Nizam Shah regained control in 1507, yet the territory slipped from Ahmadnagar’s grasp again after his death in 1508.

The history of Galna during this period reflects a turbulent era of shifting power and unstable alliances. The fort’s strategic location and resources made it a highly contested prize, drawing repeated attempts at conquest and defense. The persistent efforts of the Nashik chiefs to reclaim autonomy underscore a broader resistance to external domination. Meanwhile, the Gujarat Sultanate exerted considerable influence in the wider region (commanding the loyalty of Nashik, Trimbakeshwar, and Baglan) where local rulers paid tribute and supplied troops for its service.

Dhodap Fort

Dhodap Fort, also known as Dhorapavanki or Dharablocated, near Chandwad in Nashik district, is Maharashtra’s second-highest hill fort, standing at an elevation of approximately 5,000 ft. Believed to have been built during the reign of Burhan Nizam Shah I (1509–1553) of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, it is also referred to as Dhorapavanki or Dharab.

The fort held military and strategic importance through several historical periods. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj is believed to have visited the site in 1670 CE during his return from the Surat campaign and is thought to have hidden treasures within its premises. During the Peshwa era, Dhodap Fort featured in a major conspiracy by Raghobadada Peshwa against Madhavrao Peshwa. It was later captured by the British in 1818. Captain Briggs of the East India Company, who visited that same year, remarked on the fort’s formidable defenses, artillery, and well-planned storage and water systems.

The fort contains several rock-cut chambers once used as living quarters. One large room, around 35 by 25 ft. in size, likely functioned as a granary for storing provisions such as grain, ghee, and jaggery. A small Mandir also remains within the fort. Rising nearly 400 ft. above the main structure, the fort’s summit hosts a mazar (tomb) dedicated to a pir named Bel-pir, which continues to draw devotees.

Today, the fort is a popular but challenging hiking destination. The ascent involves a steep climb that leads to a concealed rock-cut tunnel serving as the main entrance. Near the entry, two Persian inscriptions are carved into the rock—one weathered and the other still legible, recording the name of the fort’s builder. Inside the complex, a massive bastion towers above the entrance path, while to the right lies a structure believed to be the commandant’s quarters, offering a wide view of the Chandor range.

Trymbakgad or Brahmagiri Fort

This ancient fort, lying around Nashik, once revered, later became a battleground. Over time, various powers vied for their control and dominance. Their elevated positions and natural fortifications were seen as strategic places for military campaigns rather than a puja site. The forces from Delhi, driven by their imperial ambitions, endeavored to seize control of the fortress. In contrast, the Marathas were resolute in their mission to restore their former glory. For them, Trymbak Gad Fort was perhaps a representation of their historical heritage but also a strategically vital location in their ongoing quest for supremacy. As the tapestry of history continued to unfurl, the British Empire extended its dominion across India. Trymbak Gad did not escape their expansionist ambitions. The fort, perched with a commanding view and steeped in historical significance, became a focal point of interest for the British.

Jain monuments in Anjaneri

An inscription found in the Anjanari mandir (present Trimbak city) dating back to 1141 records a grant made by the Yadava rulers to the Jain mandir of Chandraprabh, the 8th Tirthankar. Even during the time, Nirkubhavansa, perhaps the local raja, also commissioned construction of Jain caves around Ankai Fort (in present day Yeola Taluka of Nashik district). It is likely that this resulted not only in Nashik's diverse and pluralistic religious traditions but also highlights the significant role played by the Yadava rulers in shaping the cultural and religious landscape of the area.

This ancient fort, lying around Nashik, once revered, later became battleground. Over time, various powers vied for control and dominance. Their elevated positions and natural fortifications were seen as strategic places for military campaigns rather than a puja site. The forces from Delhi, driven by their imperial ambitions, endeavored to seize control of the fortress. In contrast, the Marathas were resolute in their mission to restore their former glory. For them, Trymbak Gad Fort was perhaps a representation of their historical heritage but also a strategically vital location in their ongoing quest for supremacy. As the tapestry of history continued to unfurl, the British Empire extended its dominion across India. Trymbak Gad did not escape their expansionist ambitions. The fort, perched with a commanding view and steeped in historical significance, became a focal point of interest for the British.

Additionally, these forts served as places of refuge: in 1764, amidst a disagreement between Madhav Rao and Raghunath Rao over army leadership, Raghunath sought solace by retiring to Anjaneri Fort.

Nizam Shahi

The Nizam Shahi Sultanate of Ahmadnagar, founded by Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah in 1490 after breaking away from the Bahmani Sultanate, quickly extended its influence over the Nashik region. Owing to its strategic location near the trade routes between the Deccan plateau and Gujarat, Nashik became a valuable frontier district, often caught in the crossfire between Ahmadnagar, the Gujarat Sultanate, and later the Mughals. Under Nizam Shahi rule, forts such as Trimbak, Salher, Mulher, and Ramshej were fortified to secure the northern approaches to the Deccan. The local chiefs of Baglan and Trimbakeshwar were brought under Ahmadnagar’s control through a mix of military pressure and alliances, though they remained prone to rebellion whenever central authority weakened. The fertile Godavari basin and Nashik’s position as a pilgrimage hub also contributed to its significance, prompting the Nizamshahi rulers to station trusted commanders in the area and impose revenue systems that blended local hereditary rights with central oversight. Nashik remained a contested zone throughout the 16th and early 17th centuries, repeatedly changing hands during the long Mughal: Ahmadnagar conflicts until the Sultanate’s eventual annexation by the Mughals in 1636.

Rise of Marathas

After the Mughals had annexed the Nizam Shahi of Ahmednagar in 1636, they shifted their focus on the declining Adil Shahi kingdom. At the same time Chhtrapati Shivaji Maharaj (1630-80 CE) of the Bhonsale dynasty (S/o of Shahji Bhonsale, an Adilshahi Commander and Jijabai Bhonsale), initiated his rebellion against the Adil Shah in 1646 when, at the age of 16, he captured the Torna Fort (currently in Pune).

He first fought against the Adil Shahi forces and later clashed with the Mughals, who eventually compelled him to accept the Treaty of Purandar. Following the treaty, he was imprisoned in Delhi for a time. Upon his return in 1606, he resumed hostilities on a larger scale, swiftly recapturing all the forts lost under the treaty’s terms. Maratha generals such as Prataprao Gujar and Moropant Trimbak expanded these campaigns, levying chauth and capturing the forts of Aundha, Patta, and Salher, though these were soon retaken by the Mughals. He is also recorded to have raided Galna in 1679. After his death in 1680, the region was highly contested with the hill-forts experiencing a constant change in ownership.

In the early 1700s, the Baglan province was compelled to submit during Aurangzeb’s Deccan campaigns. Local families, such as the Povars or Dalvis of Peint (now Peth in Nashik district), resisted but were captured, sent to Delhi, and executed on Aurangzeb’s orders. Despite the outcome, their actions illustrate continued local resistance to imperial authority.

Later Marathas and the British

After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Deccan underwent a significant period of political transition and realignment. The Marathas emerged as a major power, while former Mughal officials, such as Asaf Jah I (Nizam-ul-Mulk), established independent domains. Asaf Jah I founded the Nizam dynasty in Hyderabad, initiating a polity that would continue until Indian independence in 1947.

During this period, Nashik, administered by a governor based in Baglan, remained under Nizam control. In 1760, a major confrontation occurred between the Nizams and the Marathas. Following this conflict, Salabat Khan surrendered the fort of Sinnar along with several other forts to the Marathas, and the southern portion of Nashik came under Maratha administration. This transfer of territory reflected both the territorial expansion of the Marathas and the diminishing authority of the Nizams in the region.

Under Maratha control, Nashik saw continued religious and architectural activity. Notable constructions included the Rameshwara Mandir and the Naroshankar bell commissioned by Peshwa Naroshankar Raje Bahadur, the Kapaleshwara and Sundar Narayana temples built by Chandrachud, and the reconstruction of the Kalaram Mandir in 1790 by Peshwa Rangarao Odhekar. The Marathas retained control over Nashik until their defeat in 1818.

Before the British could take possession, the Marathas, specifically the Holkars of Indore, reclaimed the fort. This control lasted until December 1804, when Captain Wallace of the British forces captured the fort of Galna from the Holkars, marking yet another transfer of power in its history.

Kalaram Mandir

The Kalaram Mandir, located in the Panchavati area of Nashik, was reconstructed in 1782 under the patronage of Sardar Rangrao Odhekar. According to local tradition, the temple stands on the site where Bhagwaan Ram is believed to have resided during his exile, as described in the Ramayan. The construction, which spanned twelve years and employed approximately 2,000 laborers, features black stone murtis of Ram, Sita, and Laxman, each about two feet in height. The Mandir serves as a major religious center, particularly during the Ramnavami festival in the Hindu month of Chaitra (March–April), attracting devotees from across the region.

Colonial Period

The 19th century marked a new chapter in Nashik's history, as the district was drawn into the final conflict between the Maratha Empire and the rising British power. During the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818), Nashik’s strategic location and its formidable hill forts transformed the region into a key theater of military operations.

Fortresses such as those in Trimbak and, most notably, Malegaon became focal points of intense conflict. The Malegaon fort, constructed in 1740 by the Peshwa’s general Naro Shankar Raje Bahadur, held a vital position at the confluence of the Girna and Mausam rivers. Recognizing that its capture would grant them access to the Maratha heartland, the British made the fort a primary objective.

The Marathas offered staunch resistance, understanding that these forts held both strategic and deep value. Despite these efforts and numerous skirmishes, British forces ultimately prevailed. In 1818, after a significant siege at Malegaon, they wrested control of Nashik from the Holkars, marking the end of Maratha rule and the beginning of the colonial era in the district.

The Establishment of British Rule and a New District Formation (1818–1869)

By March 1818, all of the Holkar dynasty's possessions in Nashik were brought under British control. In the years that followed, the British government consolidated its administration in the region. In 1869, Nashik district was formally established as part of the Central Division within the Bombay Presidency.

The new district initially included twelve subdivisions: Malegaon, Nandgaon, Yeola, Niphad, Sinnar, Igatpuri, Nashik, Peth (present-day Peint), Dindori, Kalvan (present-day Kalwan), Baglan, and Chandori. Administratively, Nashik was placed under the jurisdiction of the Khandesh collectorate. This structure has largely been maintained to the present day, with the later addition of a few more talukas like Trimbakeshwar, Surgana, and Chandwad.

First War of Independence in Nashik (1857)

After Nashik fell under British control, the next significant event in its history was the 1857 revolt. While the revolt was widespread and involved numerous territories, it was not universal across India. The revolt began in Meerut and quickly spread to several parts of North and Central India, with regions like Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow becoming major centers.

Nashik, however, emerged as a focal point for resistance during a time when other regions in southern and western India seemed relatively calm. The Bhil community, one of the first indigenous communities to inhabit Nashik, contributed heavily. Despite their lack of modern weaponry compared to the technologically superior British, the Bhils displayed remarkable courage and resilience.

Bhagoji Naik, a former officer from the Ahmednagar police and a man of influence from the village of Nandur Shingote in Sinnar, united the Bhils of South Nashik and Ahilyanagar. They confronted British forces led by Lieutenant Thatcher on a hill near the Pune-Nashik road.

In response to the Bhil resistance, the British established a Koli corps of 600 men, leveraging the traditional rivalry between the Kolis and Bhils. In a subsequent skirmish, Bhil leaders Bhagoji and Harji led their people against the Koli Corps. This confrontation led to heavy losses for the Bhils, including the deaths of Bhagoji and his son, Yashvant. By April-May 1859, out of the 49 Bhils involved in the battle, 45 had perished, including their leader, Bhagoji.

Despite the setbacks, the resistance continued. On December 6th, reports came in about an attack on the Trimbak treasury by Bhils and Thakurs. Search operations in the surrounding hills led to the capture of several locals. A Thakur named Pandu confessed his role and mentioned a Trimbak Brahman adviser behind the uprising. Despite being outnumbered, poorly equipped, and eventually succumbing to British forces, the Bhils’ resistance highlighted their resolve for freedom and showed the wider discontent prevalent across India at the time.

Cultural and Civic Developments in Colonial Nashik

Sarvajanik Vachanalaya

The Sarvajanik Vachanalaya in Nashik, established around 1862 during the British era, stands as one of India's earliest public libraries and reading rooms. Situated near Shalimar Chowk, the multi-storied institution housed a remarkable collection of 175,000 books in English, Marathi, Hindi, and Sanskrit. Beyond being a library, this institution embodied a cultural movement, serving thousands of readers daily at its main library and the Sarkar Wada branch, all free of charge. The Sarvajanik Vachanalaya showcased the cultural and communal aspects of the institution, emphasizing access to education and the value Nashik placed on literacy.

Nashik News

In 1864, a notable milestone in Nashik's cultural and media landscape was achieved with the establishment of the region's first newspaper, 'Nashik News.’ It not only chronicled the happenings of the time but also became a platform for expressing opinions, sparking discussions, and providing a voice to the people of Nashik. Its inception laid the foundation for a thriving media presence in the region and set the stage for further journalistic endeavors.

Natural Disasters and Urban Development

The Great Flood of 1872

The Girna River, a major tributary of the Godavari, flows through the Nashik and Jalgaon districts. While the river sustained the district, it also triggered destructive floods, such as the one that occurred in 1872.

According to the Gazetteer (1883), this devastating flood began on the 14th of September, as heavy rains cascaded over Malegaon, persisting throughout the night until noon the next day. In the early morning of the 15th, the Mausam, a local river, surged and inundated large parts of the district. The forceful waters undermined earthen walls and sun-dried brick structures, swiftly toppling numerous homes.

The epicenter of the distress lay in the valley of the Girna. The Gazetteer records that over 1,500 houses suffered damage, with nearly 1,200 of them being completely obliterated. The monetary toll was staggering, with property losses amounting to over £7,500 (Rs. 75,000) and the estimated value of destroyed buildings reaching about £13,500 (Rs. 1,35,000). The agricultural heartlands bore the brunt of the deluge, as crops and lands across 128 villages were washed away, rendering vast stretches unfit for tillage.

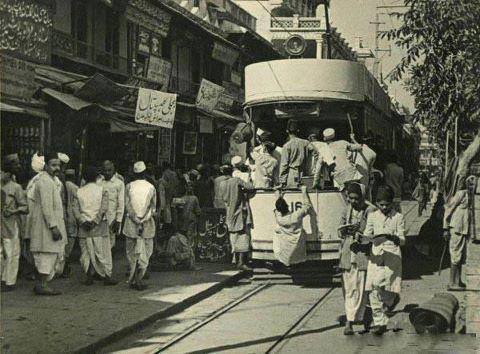

Nashik Tram

In 1889, a significant development transformed the cityscape of Nashik with the inauguration of the Nasik Tram. Its tramcars began their journeys from the Old Municipal Building on the main road, winding their way to the Nasik Road railway station. This new mode of transportation brought unprecedented ease and accessibility to the people, enhancing connectivity within the city.

For a remarkable span of 44 years, the Nasik Tram faithfully served the residents of Nashik, becoming an iconic feature of daily life. Its tracks became a representation of progress and modernization, leaving an indelible mark on the city's history as it embraced advancements in urban mobility.

Nashik in the Freedom Struggle

Rise of Revolutionary Societies

Nashik emerged as a significant hub in the fight for freedom, drawing individuals from neighboring regions to join the independence movement. To truly grasp the historical context, one must realize that during that era, the spirit of the freedom movement had already taken root in the district. Vinayak Savarkar's birthplace, Bhagur, stood as the genesis of a movement that would ignite the hearts of countless patriots.

These clandestine efforts and the rise of secret societies underscore the pivotal role Nashik played in India's struggle for independence. In 1899, Vinayak Savarkar and his brother Ganesh Savarkar laid the foundation for Mitra Mela, a secret revolutionary society based in Nashik. This initiative was part of a larger network of similar groups operating across Maharashtra. In 1904, Mitra Mela underwent a transformation and emerged as the Abhinav Bharat Society (Young India Society). United in their mission, these societies staunchly believed in the necessity of armed rebellion to challenge British rule. The name 'Abhinav Bharat' was bestowed by Vinayak Savarkar, who drew inspiration from Giuseppe Mazzini's "Young Italy" movement.

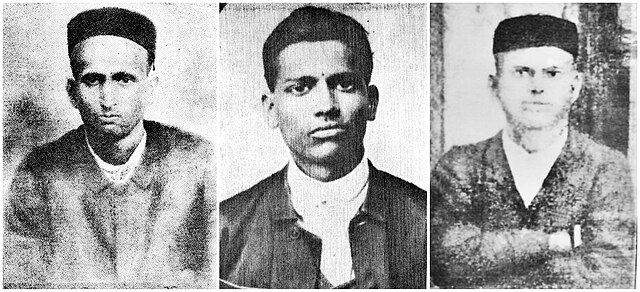

The Nashik Conspiracy Case (1909)

This revolutionary fervor culminated in the infamous Nashik Conspiracy Case of 1909. On 21 December 1909, 18-year-old Anant Laxman Kanhere, who had joined the secret society in Nashik, assassinated A.M.T. Jackson, the District Magistrate. The assassination took place at the Vijayanand Theatre, where Jackson was watching a play staged in his honor. Resentment against Jackson had been growing, particularly after he placed Ganesh Savarkar on trial.

Kanhere was apprehended immediately after the act. His actions were woven into a narrative of a broader conspiracy to overthrow British rule, and he was officially implicated in the case. The assassination sent ripples of concern through Pune and Mumbai, bringing the nationalist movement under heightened scrutiny and leading to the full enforcement of restrictive laws like the "Seditious Meetings Act."

The case implicated other revolutionaries associated with the Abhinav Bharat Society, including V.D. Savarkar, Ganesh Savarkar, and N.V. Kelkar. Anant Laxman Kanhere faced trial in a Bombay court and was executed in Thane prison on 19 April, 1910, along with his associates Krishnaji Gopal Karve and Vinayak Ramchandra Deshpande. The trial also led to the arrest and deportation of the prominent leader Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

The Nashik Satyagraha

A couple of decades after the revolutionary phase, the struggle for freedom in Nashik took a new turn. In 1930, the Nashik Satyagraha took center stage, led by Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. This movement aimed to secure the right of Dalits to enter the revered Kalaram Mandir. The following year, in 1931, a significant gathering of the Bombay Province Charmkar Parishad took place in Nashik to discuss aspects of the Second Round Table Conference, which Dr. Ambedkar was set to attend. Reinforcing his commitment to social justice, Dr. Ambedkar organized another temple entry movement in Nashik in 1932, advocating for the eradication of untouchability.

Alongside these movements for social reform, the spirit of nationalism was also kindled through literature. Nashik was home to poets such as Govind Trimbak Darekar, also known as Kavi Govind, whose patriotic compositions, including ‘Laghu Abhinav Mala,’ encouraged resistance against colonial rule.

As evidenced by such figures, Nashik nurtured several freedom fighters and played an integral role in India's struggle for independence. The city was a hotbed of revolutionary activities and movements against British rule. Apart from these documented figures and events, Nashik was also home to many unrecorded activists who participated in various capacities. The district's legacy in the freedom struggle is therefore rich and multifaceted, reflecting both its resistance to colonial rule and its fight for social justice and equality.

Modern Agricultural Identity: Table Grape Revolution of Ojhar (Ozar)

The late colonial period saw a remarkable agricultural transformation. In 1925, in the town of Ojhar, a visionary pioneer named Raosaheb Jairam Krishna Gaikwad initiated what would become a grape revolution. His efforts in the cultivation and production of table grapes marked the beginning of a new agricultural era for the region. This humble undertaking laid the groundwork that would, in the following decades, fundamentally transform the district's economy and identity.

Sant Janardan Swami

Sant Janardan Swami (Mahanubhav) was a 20th-century saint who made a significant contribution by establishing a major spiritual centre for the Dattatreya tradition in Nashik. He was born in 1914 and was a balyati (celibate from childhood). His

His primary karmabhoomi became Tapovan in Nashik, which he transformed into a vibrant spiritual hub. He was a siddha (realised master) known for his simple teachings, emphasis on Namasmaran (chanting the divine name), and selfless service. He established numerous ashrams and Mandirs, reviving faith for millions. His Samadhi Mandir at Tapovan, Nashik, attracts devotees from all over Maharashtra

Post-Independence

When India was granted independence in 1947, the Bombay Presidency, including Nashik, became part of the new Bombay State. On 1 November 1956, Bombay State was reorganized under the States Reorganisation Act, absorbing various territories. Subsequently, on 1 May 1960, Bombay State was dissolved and split on linguistic lines into the two states of Gujarat and Maharashtra, with Nashik becoming a district within the new state of Maharashtra.

Post-1960: A Hub of Agriculture and Industry

Following the formation of Maharashtra, Nashik district embarked on a journey of remarkable growth and diversification. Key sectors like agriculture and industry expanded significantly, while the district also made major strides in education and healthcare, establishing itself as an important regional hub.

The Grape Revolution

In the decades following independence, the pioneering agricultural efforts initiated in Ojhar during the colonial era came to full fruition. The cultivation of table grapes expanded dramatically, transforming the agricultural landscape of Nashik. What began as a local venture transcended national borders, as Nashik’s grapes came to be exported across the world to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. This success paved the way for a thriving wine manufacturing industry, cementing Nashik's modern reputation as the ‘Wine Capital of India’ and serving as a testament to the entrepreneurial spirit that originated in the soil of Ojhar.

Modernization and a Vision for the Future

In recent times, Nashik has continued to embrace rapid urbanization and modernization. The establishment of industrial zones like Ambad has attracted further investment, cementing the city's position as a vital hub for trade and commerce. On the administrative front, proposals for the bifurcation of the district and the creation of a separate Malegaon district have emerged, reflecting a continued effort to streamline governance and address the region's evolving development needs.

Sources

Bombay Government Records. 1958. "History of the Freedom Movement in India." Vol. 2. Government Central Press, Bombay.

Cyril Manton Harris. 2013. Illustrated Dictionary of Historic Architecture. Courier.

Eugen Hultzsch. 1906. "Epigraphia Indica." Vol. 8. Archaeological Survey of India, Government of India, New Delhi.

Govind Trimbak Darekar. The Patriotic Poet. Digital District Repository Detail.https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/district-reopsi…

H.S. Thosar. 1990.The Abhiras in Indian History. Vol. 51. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44148188.pdf

Jadunath Sarkar, tr. 1949. Ain-i-Akbari of Abul-Fazl-Allami. Vol. 2, ed. 2. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta.

James Fergusson and James Burgess. 2013. The Cave Temples of India. Cambridge University Press.https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/The_C…

James G. Lochtefeld, ed. Knut A. Jacobsen. 2008. The Kumbh Mela Festival Processions. South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge.

James Grant Duff. 1912. A History of the Mahrattas. Vol. 1. R. Cambray and Co., Calcutta.

James Macnabb Campbell. 1883. "Gazetteer Bombay Presidency." Vol. 16. Nasik.

John Briggs, tr. 1910. Ferishta and Mahomed Kasim, History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India, Till the Year A.D. 1612. Vol. 3. Central Secretariat Library.https://indianculture.gov.in/rarebooks/histo…

Kurt Titze and Klaus Bruhn. 1998. "Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence." ed. 2. Motilal Banarsidass.https://books.google.com/books?id=loQkEIf8z5…

M. S. Naravane. 1997. A Short History of Baglan. Palomi Publications, Pune.

Mandar Anant Thakur. 2008. People’s Role and Contribution in Nasik Kalaram Temple Entry Satyagraha. Vol. 69. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147245

Ojas Borse. 2017. Contribution of Bhil Adivasis of Khandesh in the Revolt of 1857. Vol. 3, no. 3.Rural South Asian Studies.http://ruralsouthasia.org/wp-content/uploads…

Om Prakash Verma. 1970. The Yadavas and their Times. University of Michigan, Michigan.

Population Census, Jain Population in India.https://www.census2011.co.in/data/religion/6…

Reginald George Burton. 1910. "The Mahratta and Pindari War." Government Press, Shimla.

Sherwani H.K. 1973. "History of Medieval Deccan, 1295-1724." Vol. 1.

Sudama Misra. 1973. "Janapada state in ancient India." Bharatiya Vidya Prakasana.https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Janap…

Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya. 1974. Some Early Dynasties of South India.https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Some_…

Vaishali Balajiwale. 2015. Project Trimbak, not Nashik, as the place for Kumbh: Shaiva akhadas. DNA.http://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-projec…

Valmiki. "Ramayan: Aranya Kanda - The Forest Trek." Book 3.https://www.valmikiramayan.net/utf8/aranya/s…

Vikram Doctor. 2013. Kumbh mela dates back to mid-19th century, shows research. Economic Times.http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.