Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Inamgaon and the Rise of Chalcolithic Cultures in Pune

- Satavahana Control and the Trade Route Through Naneghat

- Spread of Buddhism and the Cave Complexes of Pune

- The Western Kshatrapas and Junnar Under Nahapana

- Rashtrakuta Patronage and the Pataleshwar Caves

- The Devagiri Yadavas and Hemadpanti Traces in the Pune Region

- Sant Dnyaneshwar

- Sant Sopandeo

- Medieval Period

- The Khilji Conquest and Killa-e-Hissar

- Junnar and Chakan Under the Bahmani Sultanate

- Nizam Shahi (1490-1636 CE)

- The Rise of the Marathas (1600 onwards)

- Sant Tukaram

- Chhatrapati Shivaji Bhosale

- Torna Fort

- Shivaji Consolidates Power

- The Treaty of Purandar

- The Battle of Sinhagad in 1670

- Chhatrapati Sambhaji Bhonsale (1657-1689)

- Tulapur

- Chhatrapati Rajaram Bhosale

- Battle of Khed 1707

- Shaniwar Wada as the Seat of the Peshwas

- Balaji Vishvanath Bhat, first Peshwa (1662-1720)

- Bajirao Peshwa, Second Peshwa (1700-1740)

- Battle of Wadgaon/Vadgaon, 1779

- Poona Plunder, 1797

- Battle of Poona, 1802

- The Poona Plunder, 1802

- Famine, 1802

- Restoration of Baji Rao II

- Colonial Period

- Treaty of Poona, 13 June 1817

- Battle of Kirkee, 5 November 1817

- The Surrender of Pune to the British in 1817

- Battle of Koregaon, 1 January 1818

- Colonial Administration

- Revenue System

- Ramoshis of Pune

- Koli Uprising

- The First War of Independence, 1857

- Struggle for Independence

- Chitrashala Steam Press

- Kaal Newspaper

- Mulshi Satyagraha

- Electricity in Pune

- The Paisa Fund and Swadeshi Movement

- Handmade Paper Institute

- Post-Independence

- Sources

PUNE

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Pune district, located along the eastern edge of the Sahyadris in western Maharashtra, is known today for its universities, research institutions, and expanding IT sector. But long before its modern prominence, this region held political and cultural significance across several centuries. One of the earliest traces of habitation is found at Inamgaon, a settlement on the banks of the Ghod River, where excavations by the Deccan College have revealed occupation layers linked to the Jorwe and Malwa cultures of the second millennium BCE. Over the centuries, the region continued to hold strategic and cultural value, especially as trade and political routes extended across the Deccan.

By the early historic period, the inland town of Junnar had grown into a commercial hub, connected by the Naneghat pass to ports along the Konkan coast. The pass itself, carved through the Sahyadris, is of much significance. Notably, it is here that one of the earliest inscriptions in Maharashtri Prakrit, composed in early Brahmi script, was commissioned in the 1st century BCE by Queen Naganika, who was the consort of the Satavahana ruler Satakarni I. Fascinatingly, it is mentioned in the Pune district Gazetteer (1891), that this inscription is among the oldest known records in the linguistic tradition that would later give rise to Marathi. In the eighteenth century, Pune City particularly became the administrative seat of the Peshwas, hereditary ministers of the Maratha Confederacy, whose rule left a lasting imprint on the region’s institutions and built environment. Later, under British rule, Pune served as a chief military centre in the Deccan region. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Pune was notable as a major center of revolutionary activity; it became associated with leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak and, later, Mahatma Gandhi, who resided here during certain periods of political activity.

Etymology

The derivation of the name Pune has long been a matter of conjecture among historians, and the region itself, in the slow march of centuries, has borne many appellations. The colonial district Gazetteer (1885) preserves the view, favoured by certain scholars of the British period, that “Poona”—as the settlement was then styled—may be identified with Pumiata, a city placed upon the map of the Egyptian geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd Century CE.

The earliest allusion to the district appears in the Naneghat inscription of the first century CE, when the Satavahanas held sway. Though the name Pune is absent from this ancient record, later tradition and epigraph alike suggest that the site at the confluence of the Mula and Mutha was known in earlier days as Punyapur which means “the Sacred Town.” Interestingly, local lore ascribes the title to the Punyeshwar Mandir, a shrine once standing by the waters of the Mutha; and there are those who, with a poet’s licence, connect the tract with the legendary Dandakaranya forest of the Ramayan.

More definite traces of its origins come from a copperplate charter unearthed near Talegaon, on the road from Bombay to Pune. This document, dated 786 CE, records a grant by Krishnaraj of the Rashtrakuta line to a village styled Kumarigram (the modern Koregaon), situating it in the district of Punnat, bounded by the Khadir Hills on the south and the Mula River on the north. In that age, the region was known as Punya Vishaya or Punaka Vishaya; by the tenth century, the form Punaka Wadi is also mentioned.

In the 16th century, the Bengali saint Chaitanya, passing through these parts, speaks of Purnanagar. A curious note is added by a thirteenth-century Arab record, in which a modest settlement is designated Kasba Pune; the name, in its modern simplicity, by which the city is known today.

Ancient Period

Inamgaon and the Rise of Chalcolithic Cultures in Pune

The earliest chapter in Pune district’s history begins not with inscriptions or dynasties, but with buried traces of Chalcolithic life along the banks of the Ghod River. It is here, at the site of Inamgaon, that archaeologists have uncovered the most substantial evidence of early habitation in the region. Archaeological excavations conducted here reveal that Inamgaon was first inhabited by communities associated with the Malwa culture, who were likely migrants from central India and brought with them knowledge of agriculture, animal husbandry, and pottery.

By around 1400 BCE, the Jorwe culture came to dominate the settlement. Marked by distinctive pottery styles and organized agrarian lifestyles, the Jorwe phase represents a maturation of early Deccan cultures. Excavations at Inamgaon have yielded domestic structures, granaries, and dwelling pits, indicating a populous and enduring settlement. It is also suggested that the name "Inamgaon" derives from the word inam, meaning land grant—though no formal records survive to confirm this.

Of the Jorwe culture sites across Maharashtra, Inamgaon remains one of the most extensively studied, and the volume of pottery and domestic remains recovered here has led many scholars to regard it as a principal centre to understand life during the Chalcolithic period in the region.

Satavahana Control and the Trade Route Through Naneghat

The subsequent centuries saw the rise of the Satavahanas, whose influence extended across much of the Deccan. Though their capital was at Paithan, the Satavahanas maintained a visible presence in the Pune district, as suggested by the archaeological and inscriptional evidence from Junnar and Kasba Peth. The latter, now the oldest quarter of Pune city, yielded artefacts in 2003 that are believed to date from the Satavahana period, confirming the dynasty’s early presence in the region.

Of particular importance is the mountain pass at Naneghat in the Junnar taluka. At this time, the pass functioned as a critical trade corridor linking the Satavahana heartland with the western ports of Sopara and Kalyan. The name Naneghat, or “coin pass,” is thought to reflect the tolls once collected from traders traversing this route. A remarkable 2,000-year-old stone urn, situated beside the pass, supports this theory.

The caves at Naneghat, hewn during the early Satavahana period, served both commercial and religious purposes. They offered rest and shelter to travellers and were likely maintained as part of the state’s broader patronage of Buddhist and Vedic traditions. One of the most significant discoveries here is the famous Naneghat inscription, dated between 90 BCE and 30 CE. Engraved in Brahmi script, it is mentioned in the colonial district Gazetteer (1885), that the text opens with invocations to deities from both Vedic and Puranic traditions and provides the earliest epigraphic record from western India. It notably mentions Queen Naganika, consort of Satakarni I, who is also credited with commissioning commemorative coins following an Ashwamedha Yajna held at Junnar.

These early coin issues—struck in potin, a brittle alloy also known to Roman mints—offer rare insight into matrilineal authority in early Deccan polity. Few such coins of this nature survive, but their existence speaks to a unique moment when political and ritual sovereignty were expressed through the figure of a queen.

Spread of Buddhism and the Cave Complexes of Pune

Simultaneous with the development of inland trade, Buddhism flourished along the commercial corridors of the Western Ghats. The Bhaja Caves, situated above the modern highway near Lonavala, form part of an extensive network of early Buddhist cave shrines that emerged in the 2nd century BCE. These caves—along with nearby sites at Karla and Bedsa—were typically established along trade routes and served as monastic shelters for itinerant monks and merchants. Junnar, very notably, is home to one of the largest concentrations of rock-cut cave complexes in India.

The Western Kshatrapas and Junnar Under Nahapana

By the first century CE, the district appears to have come under the influence of the Western Kshatrapas, an Indo-Scythian dynasty that ruled large portions of western and central India. Of these rulers, Nahapana is the most firmly associated with the Pune district. Inscriptions bearing his name have been found in the caves at Junnar, while those of his son-in-law, Ushavadata, appear in the Karla caves.

The district colonial Gazetteer (1885) records Nahapana to be a Parthian or Saka viceroy ruling between 40 and 120 CE. His inscriptions, discovered in the caves at Junnar, reveal that the region served as an administrative or possibly royal centre during his rule.

Trade with the Roman world is also documented in this period; the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions that Roman goods arriving at Kalyan (Thane district) and Sopara (Palghar district) would be transported inland through Junnar, eventually reaching the Satavahana capital at Paithan (Sambhaji Nagar district).

The Kshatrapa rule, however, was relatively short-lived. Around 130–150 CE, Nahapana was defeated by Gautamiputra Satakarni of the Satavahana dynasty, who, according to inscriptions at Nashik, reclaimed much of the western Deccan and melted down Kshatrapa coins for reissue.

After the decline of the Satavahanas, the Early Chalukyas (also known as the Badami Chalukyas) ruled a vast part of Western India, including Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. Although direct inscriptions from the Early Chalukyas (often referred to as the Badami Chalukyas) have not been found within Pune district, their dominance over adjacent regions such as Ahilyanagar, Solapur, and Satara suggests that their influence extended into this area as well.

There is however, one structure, which is frequently associated with the Chalukya period; the Bhuleshwar Mandir, located near Yavat in eastern Pune. While precise dating remains uncertain, architectural features of the mandir point toward an 8th–9th century CE origin, consistent with Chalukyan architectural styles.

Rashtrakuta Patronage and the Pataleshwar Caves

By the mid-8th century CE, the Rashtrakutas rose to prominence in peninsular India, establishing their capital at Manyakheta and supplanting the Chalukyas in much of the Deccan. From 760 to 973 CE, the Rashtrakutas held extensive sway over Maharashtra, including the region now forming Pune district.

Although no copper-plate grants or royal inscriptions from the dynasty have yet been discovered within Pune itself, their influence is manifest in the rock-cut Pataleshwar Mandir, situated in present-day Shivajinagar. Carved from a single basalt outcrop, the cave temple is stylistically aligned with the Rashtrakuta period and suggests sustained Shaiva patronage under their rule.

The complex comprises a circular Nandi mandap supported by sixteen pillars, a central shrine housing a Shiva linga, and a nearly square sabha-mandapa ringed with columns. Carvings of the Saptamatrikas, Tripurantaka, Gajalakshmi, and Anantasayin Vishnu indicate an integration of both Shaiva and Vaishnava iconography, consistent with the religious eclecticism promoted by the Rashtrakuta sovereigns.

The Devagiri Yadavas and Hemadpanti Traces in the Pune Region

The final phase of the ancient period in Pune district corresponds with the rule of the Devagiri Yadavas (c. 1150–1310 CE), a dynasty that exercised control over much of the Deccan from their capital at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad). During this time, Pune appears in historical records as Punaka Wadi or Punewadi, indicating that there was a modest but settled locality within a larger administrative framework here.

The architectural legacy of this period is sparse but suggestive. Scattered remains of Mandir in the Hemadpanti style—named after Hemadri or Hemadpant, the minister of Yadava king Mahadeva and his successor Ramachandra—are found at sites such as Bhamburda and Nageshwar in Pune. These mandirs, constructed without mortar and characterized by their black basalt masonry, point to a standardized technique associated with Yadava temple-building throughout the western Deccan.

During the period in question, the greater portion of the territory appears to have been apportioned among Maratha and Koli hill paligars, who held their estates under the suzerainty of the Devgiri Yadava dynasty. Of the chieftains then holding sway, mention in the colonial district Gazetteer (1885) is made only of one Nag Naik, a Koli by caste, who possessed the fort of Sinhgad.

The inhabited portion of the region appears to have consisted of but three settlements—Kumbarli, Kasarli, and Punewadi—all of which were enclosed within a single wall, known by the appellation Pandhari Kot (the term Pandhari signifying "white" in the vernacular). This walled cluster likely formed the nucleus of what came to be known in later periods as Kasba Pune.

Sant Dnyaneshwar

Sant Dnyaneshwar, the revered 'Mauli' of Maharashtra, laid the philosophical foundation of the Warkari tradition. He was born in 1275 in Apegaon.

While his karmabhoomi for writing the monumental Dnyaneshwari was Nevasa (Ahilyanagar), his final, sacred resting place is in Alandi, Pune district. After completing his life's work of democratising spiritual knowledge, he voluntarily entered into a state of Sanjivan Samadhi (a conscious departure from the mortal body) in Alandi at the young age of 21. Alandi is therefore the Samadhi-sthal of the sant who started the great Warkari tradition, and the annual Palkhi (pilgrimage) from Alandi to Pandharpur is one of the most important events in Maharashtra.

Sant Sopandeo

Sant Sopandeo was the younger brother of Sant Dnyaneshwar. He was also a saint of the Varkari Sampraday. Sopan was born in 1277 at Alandi in Pune. He attained samadhi at Saswad near Pune. He wrote a book, the Sopandevi based on the Marathi translation of the Bhagavad Gita along with around 50 abhangs.

Medieval Period

The Khilji Conquest and Killa-e-Hissar

The medieval political history of Pune district begins in the early 14th century, when the armies of the Delhi Sultanate expanded into the Deccan. In 1317 CE, the Khilji dynasty, then ruling from Delhi, defeated the Devagiri Yadavas and brought the region under their control. Soon after, the Tughlaqs succeeded the Khiljis as overlords of the Deccan. It was during this time that a new phase of urban and administrative development began to take shape along the banks of the Mutha River.

A noteworthy figure of this early period was Bariyah Arab, a military commander under the Khilji regime. In 1290 CE, he constructed a fortified enclosure known as Killa-e-Hissar in the locality now known as Kasba Peth. This structure served as a military post and residential settlement. Near the fort, Bariyah Arab is believed to have laid out one of the earliest markets in the district. This artisan colony, referred to as ‘Kasbah’ in Persian (meaning a fortified marketplace), later lent its name to the surrounding settlement, which became known as Kasabe Pune.

The remains of the original stone steps leading to the western gate of the fort—known as the Konkan Darwaja—are still visible today.

Junnar and Chakan Under the Bahmani Sultanate

With the weakening of Tughlaq authority in the latter half of the 14th century, the Bahmani Sultanate emerged as the new power in the Deccan. Founded by Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah in 1347 CE, the dynasty controlled much of the plateau for nearly two centuries. Within this administrative structure, Pune fell under the Junnar Pargana, a region of strategic and economic importance.

The reign of Muhammad Shah Bahmani (1358–1375 CE) was marked by prosperity, though it was later overshadowed by the prolonged Durgadevi famine (1396–1407 CE), which severely affected the region. The famine, compounded by recurring droughts, forced many cultivators to abandon their fields, and parts of the land were reorganised under new revenue arrangements.

In 1443 CE, Mahmud Gawan—vizier to the Bahmani Sultanate and a key administrative reformer—appointed officers to oversee the Parganas. Chakan, located in present-day Pune district, became a principal military post. Around this time, Sangramdurg Fort at Chakan was constructed. The area remained under the supervision of Bariyah Arab, who continued to command operations from Chakan and was responsible for the construction of a fort on the mound locally referred to as gaon-pandhar.

In the 15th century, Pune assumed a more prominent role in the Bahmani military machinery. In 1443 CE, an officer of the Sultanate, Malik-ul-Tujar, was stationed at Chakan, a fortified settlement in the northern part of the district. However, internal dissent within the Bahmani ranks led to his death, along with hundreds of soldiers. The political fallout from this incident triggered a siege at Chakan, and exposed deeper divisions within the Sultanate’s forces.

To restore order and prevent further rebellion, Mahmud Gawan introduced administrative reforms. As part of these changes, Pune and its surrounding forts were apportioned among nobles, each responsible for maintaining a garrison and drawing pay from the royal treasury.

Nizam Shahi (1490-1636 CE)

In 1477, along with other districts, Pune district was handed over from the Bahmanis to Malik Ahmad who established the Nizam Shahi empire (also known as Ahmednagar Sultanate). Malik Ahmad ( see Ahilyanagar for more ) set up his command post at Junnar ( a taluka in the present day district). The highlight of his military career was the capture of Shivneri (also known in some areas as Shivneri fort) which held 5 years worth the revenue of the entire Maharashtra region. Such a vast resource equipped him to give his officers and the troops who helped him acquire the western and south-western parts of Pune such as Lohagad, Singhad, and Purandhar. Malik Ahmad took charge of the state after his father, who was a Bahmani minister until 1486 CE. When the Bahmani troops attacked him, he went to Chakan and killed the leader. The Gazetteer (1885) mentions that Malik Ahmad was the first one to scale the walls and helped his 17 men to get past the garrison. After conquering Chakan from the Bahmanis, Malik Ahmad overpowered the Bahmani army in Bagh. He made it the capital in the year 1494 CE and set up the new city of Ahmednagar, until it was taken over by the Mughals in 1600.

Except Indapur (a town in present Pune district), which belonged to the Bijapur Kingdom, all other parts of the present Pune district were mostly governed by Ahmednagar kings. During this time, revenue was collected by farmers and they reported to the Government agent, or amil, who also resolved civil disputes. At the time, Hindus who showed exemplary performance were honoured with the titles of Raja, Naik, or Rao.

The Nizam Shahi rule was interesting in many ways. The king’s popularity among the public determined their fate. For instance, Burhan Nizam (1508-1553 CE), the second ruler of Ahmednagar, was overpowered by Bahadur Shah’s army. He believed that this occurred as the peshwa, or minister, was disliked and hence, he was replaced.

Under the reign of Salaabat Khan (1564-1589 CE), Ahmednagar witnessed affluence that had ceased since the time of Mahmud Bahmani. He, however, was forced to decamp due to the dissension among the members of his court.

Many regions in and around Pune developed during the time. Malkapur (now known as Ravivar Peth), for instance, is known to have been set up by Malik Ambar during the Shahi rule. Murtazabad (Shaniwar Peth) was founded by Murtaza Nizam Shah who was the ruler of Ahmednagar. Even Shahapura (now Somwar Peth) is known to have been set up during this period.

The Rise of the Marathas (1600 onwards)

The Maratha and the Peshwai rule are perhaps the most well known periods in Pune history. The Marathas came to power in parts of Maharashtra after the Nizam Shahi rule ended in these regions. The jagirs of Pune, along with the forts of Shivneri and Chakan, were bestowed upon Maloji Bhonsale (1552- 1605/1620) by Bahadur Nizam II (See Ahilyanagar for more on Maloji). Their descent is said to be traced to the royal family of the Sisodias of Mewar, though this claim is contested.

There is a fascinating account of this rise to power. In 1599, Maloji took his son Shahaji to pay his respect to his patron Lukhujirao Jadhav of Sindhkhed, who was then a chief Maratha sardar of the Ahmednagar state. Lukhuji’s daughter, Jijabai (3-4 years old), and Maloji’s son Shahaji started playing when Lukhuji teasingly asked his daughter whether she would marry him. Though this was said in jest, Maloji rose and accepted the offer of marriage. This enraged Lukhuji and his wife, yet, this marriage was solemnised when Maloji was given the epithet of ‘raja’.

After Maloji’s death, his jagir was transferred to his son Shahaji. The Nizamshai that had been under constant threat from the Bijapur sultanate and the Mughals had been under the control of Malik Ambar (1549 - 1626), an Abyssinian slave who rose through the military ranks. Malik Ambar through his administrative and military acumen and prowess with the help of loyal Maratha sardars, was able to keep both these foes at bay for quite some time. Though soon after his death, Shahaji strategically realigned with Bijapur Sultanate in 1632. In 1634, when the Mughals under emperor Shah Jahan attacked Daulatabad, which was under the control of a young Nizam Shahi prince, Shahaji took the help of Bijapur and local Brahmin officers to usurp southern parts of the Ahmednagar sultanate. The records of the Marathas in the Gazetteer (1885) assert that in return Pune was destroyed by the Mughals. This came to an end with the peace treaty between the Mughals and Bijapur in 1636 CE.

Nizamshahi was uprooted in the same year 1936, ten years after Malik Ambar’s death. Thus, putting an end to the Nizamshahi line.

Though disagreeing at first, Shahaji joined the Bijapur service and handed over the forts of Junnar, Jivdhan, Chavand, Harshira, and Kondhana (later renamed to Sinhagadh). He arranged for his family to reside in Pune where his estates were managed by Dadaji Kondadev. Dadaji trained the Shahaji’s younger son through Jijabai, Shivaji, in Warfare (archery, sword fighting, horse riding), administration and military strategy, the Maratha code of honor and Hindu traditions.

Sant Tukaram

Sant Tukaram, revered as the crowning glory (Kalas) of the Warkari movement, made an unparalleled contribution through his powerful and soul-stirring abhangs. He was born Tukaram Bolhoba Ambile around 1608 in the town of Dehu, in Pune district.

His entire life and karmabhoomi were centred in Dehu. Through his kirtans, he challenged social hierarchies, religious orthodoxy, and hypocrisy. His philosophy was a simple, direct, and often emotional devotion to Bhagwan Vithoba, which became the very heart of the Bhakti movement. His collection of poems, the Tukaram Gatha, is considered a foundational text of Marathi literature. He is famously said to have ascended to Vaikuntha (heaven) in his mortal body from Dehu, which remains a primary centre of the Warkari faith.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Bhosale

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was the founder of the Maratha Empire. He was born February 1630 at Shivneri Fort (Junnar), in the district of Pune. Shivaji Maharaj emerged to become not just a warrior but a visionary leader who laid the foundation of a powerful Maratha Empire. Shivaji was raised in Pune under the guardianship of his mother, Jijabai, and his administrator Dadoji Kondadev. Dadoji Kondadev managed Shahaji’s estates in Pune, successfully administering the region and continuing Malik Ambar’s revenue system. Pune became an important Maratha stronghold under Dadoji Kondadev’s rule, and Shivaji gained knowledge of the Maval region and its warriors (Mavalas).

Torna Fort

In 1645 with a few companions of his, Shivaji Maharaj, 15 years old at that moment took the oath of the foundation of ‘Hindavi Swarajya’ at Shri Raireshwar Mandir in Pune. Shivaji then initiated this task in 1646 when, at the age of 16, he captured Torna Fort (currently in Pune). He had come to know of the hill forts that could be easily captured as they were left under the supervision of amildar or a local agent. He exploited the weakness in the Bijapur Sultanate's defenses caused by the Sultan's illness. By leading a small force, including notable figures like Baji Pasalkar, Yesaji Kank, and Tanaji Malusare, he seized the fort of Torna, along with a large treasure. It is also said that he might’ve tricked or bribed the Bijapuri commander.

It was the first major victory and it provided a strong base in the Western Ghats, from which he could expand his control. According to the Gazetteer (1885), after capturing the fort, Shivaji’s men discovered hidden treasure in one of its structures. The treasure was believed to have been left behind by earlier rulers. Instead of keeping it for personal use, Shivaji used the treasure to fortify Torna and build Rajgadh Fort nearby (which became his capital for quite some time till he captured Raigad).

Torna Fort, also known as Prachandagad, meaning "Massive Fort," is one of the largest and tallest forts in the district. Its size, elevation, and strategic location made it an important stronghold in the Western Ghats.

Shivaji Consolidates Power

Shivaji soon assumed full control of his father’s estates in Pune and reportedly avoided paying taxes to the Bijapur Sultanate, fueling tensions with its authorities. During this period, he seized several key forts, including Bhurap and Kangori in Kolaba, as well as Tikona, Lohagad, and Rajmachi. In 1659, alarmed by Shivaji’s growing power, Ali Adil Shah II of Bijapur imprisoned his father. Shivaji began corresponding with the Mughals, who offered to recognize his position and grant him command over 5,000 cavalry. That same year, Adil Shah dispatched General Afzal Khan to kill him, but Shivaji defeated and killed Khan, capturing several forts deep within Adilshahi territory, especially around Kolhapur.

In 1660, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb—newly enthroned after imprisoning his father—sent his maternal uncle, Shaista Khan, as viceroy of the Deccan to enforce a treaty with Bijapur. Under this agreement, the Adilshahi ceded former Ahmadnagar territories to the Mughals, but Shivaji contested these lands fiercely. Shaista Khan quickly advanced from Aurangabad, capturing Pune, Chakan, Kalyan, and parts of north Konkan after heavy fighting. The Marathas were barred from Pune, and Khan’s harsh treatment of civilians, along with widespread destruction, alienated locals.

On the night of 5 April 1663, Shivaji led a daring raid. Disguised as part of a wedding procession, he and nearly 400 men infiltrated Pune in small groups. After midnight, they stormed Lal Mahal—Shivaji’s childhood home—killing guards and entering Shaista Khan’s quarters. According to tradition, Khan lost three fingers while fleeing, and his son was killed in the courtyard. The Marathas escaped under cover of darkness. Humiliated, Aurangzeb transferred Shaista Khan to Bengal.

The following year, Shivaji directly challenged the Mughal emperor by raiding the wealthy port city of Surat in 1664.

The Treaty of Purandar

In 1664, Shivaji scored major victories, defeating Bijapur forces and plundering Ahmednagar and Barcelor (a port near present-day Goa), marking a significant expansion of Maratha power.

The following year, Aurangzeb dispatched Raja Jai Singh and Diler Khan to attack Shivaji. Jai Singh advanced toward Pune, targeting Shivaji’s forts, while Diler Khan besieged Purandar. For over five months, the Mughals captured several strongholds but were harassed by swift Maratha night raids, road blockades, and forest fires. With both sides exhausted—and Shivaji’s family trapped in Sinhagad—he agreed to the Treaty of Purandar (1665), ceding 23 forts, entering Mughal service, and acknowledging Mughal suzerainty.

In 1666, Shivaji visited Aurangzeb’s court in Agra, where he was imprisoned. He later escaped but maintained a peaceful relationship with the Mughals for a few years, during which he also attacked the decaying Adil Shahi kingdom and gained sardeshmukhi and chauthai rights. In 1670, this peace fell through and Shivaji swiftly recaptured many of the forts he had surrendered under the treaty. He also in the same year raided and looted Surat for the second time.

In the same year, Shivaji mounted a campaign to retake Sinhgad, assigning the operation to Tanaji Malusare, whose actions during the battle became legendary. This, in many ways, marked the beginning of a renewed Maratha offensive in western Maharashtra.

The Battle of Sinhagad in 1670

In 1670, the fort became the site of one of the most well-known battles in Maratha history. Tanaji Malusare, military commander of the Maratha Empire and close companion of Shivaji Maharaj, led a force of around 300 Maratha soldiers in a surprise night assault against a much larger Mughal garrison commanded by Udaybhan Rathod, a Rajput officer serving the Mughals. Very interestingly, it is said that the Marathas scaled the fort’s steep cliffs with the help of a trained Bengal monitor lizard, also known as ghorpad, to secure climbing ropes.

In the battle that followed, both Tanaji and Udaybhan succumbed to their grave injuries in a violent duel, but the former’s sacrifice inspired the Marathas to continue their attack. Under the leadership of his brother Suryaji, the Marathas captured the fort. Upon learning of Tanaji’s death, according to legend, Shivaji Maharaj expressed his sorrow by uttering the phrase, “Gad aala, pan sinha gela” meaning “We won the fort, but lost the lion”. It is said that in Tanaji’s honor, the fort was thus renamed ‘Sinhagad’ meaning ‘Lion’s Fort’, and his memory lives on with his Samadhi installed at the site.

Chhatrapati Sambhaji Bhonsale (1657-1689)

Chhatrapati Sambhaji Bhonsale (1657–1689) succeeded his father after a short power tussle with his step mother Soyrabai, Under Sambhaji’s leadership, the Maratha Empire continued to expand, with successful military campaigns extending Maratha control into parts of present-day Gujarat, Karnataka, and Telangana.

In 1682, a Mughal force led by Husan Ali Khan marched from Ahmadnagar through Junnar into the Sahyadris, aiming to attack Konkan. Tensions further escalated in 1684 when Aurangzeb reimposed the jizya tax on non-Muslims. Sambhaji is believed to have been known for his commitment to religious freedom and tolerance. He allowed people of all faiths to practise their religion without interference and is recorded to have patronised various religious institutions and spiritual leaders, regardless of their faith.

It was under Sambhaji’s rule that Mughal commander Khan Jahan set up military outposts in 1685 between Junnar and Sinhagad to check Maratha resistance. As a result, Khan Jahan captured Pune and nearby regions, appointing Khakar Khan as the local governor. To resist these Mughal advances, Sambhaji allied with Sultan Akbar, Aurangzeb’s rebellious son, who sought refuge and support from the Marathas. However, according to the Bombay Gazetteer (1885), Sambhaji’s forces were intercepted and defeated near Chakan before the alliance could take full effect. The conflict intensified after the fall of Bijapur in 1686, which marked the end of the Adilshahi dynasty.

Sambhaji was also known for his patronage of the arts and culture. He supported several poets, writers, and artists of his time, including the noted Marathi poet Tukaram. Sambhaji was a patron of the performing arts, and his court was known for its music and dance performances. He also commissioned the construction of several grand temples and monuments. One of the most significant achievements of Sambhaji's reign was the establishment of a formal administration system. He created a council of ministers to assist him in governing the empire and implemented several administrative reforms to streamline the taxation and revenue collection process.

Purandar Fort

Purandar Fort holds immense historical significance, primarily as the birthplace of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj in 1657, the eldest son and successor of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Strategically located at a height of 4,472 feet in the Pune district, the fort served as a crucial defensive stronghold for the Maratha Empire, protecting the region from enemy advances, particularly from the Mughal Empire. One of the fort's most notable events was the Treaty of Purandar in 1665, signed between Shivaji Maharaj and Jai Singh I, a general of Emperor Aurangzeb, wherein Shivaji ceded 23 forts but retained control over Purandar, marking a diplomatic victory. Later, under Sambhaji Maharaj, the fort became a key base for planning resistance and guerrilla warfare against Mughal invasions. Besides its military significance, Purandar Fort also holds cultural importance with mandirs dedicated to local bhagwans such as Kedareshwar and Purandeshwar. During British colonial rule, it was repurposed as a sanatorium, a military training center, and even served as an internment camp for German prisoners during World War I.

Tulapur

Tulapur in the district holds a significant place in Maratha history due to its association with the execution of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj. Tulapur is about 40 Kilometres north-east of Pune. Tulapur village was originally known as Nagargaon and is situated at the confluence of the Bhima, Bhadra, and Indrayani rivers (historically referred to as Triveni Sangam). It is believed that the village was renamed Tulapur when Chatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj used a boat to weigh an elephant to help Adil Shahi minister, Murarpant donate silver equivalent to the weight of an elephant.

In 1689, Aurangzeb advanced towards Pune. Emperor Aurangzeb remained in Pune for a brief period between 1689 and 1707. In 1689, Aurangzeb camped at Tulapur which lies about 16 miles north-east of Pune. According to the Gazetteer (1885), Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj was captured by Mughal forces under Takarrib Khan in 1689 at Sangameshwar town (in present Ratnagiri district). He was brought to Tulapur where he was executed.

Chhatrapati Rajaram Bhosale

Rajaram Bhonsale, the second son of Shivaji, was born in 1670. In 1689, after Sambhaji's execution, Rajaram was under house arrest on the orders of his elder brother, but was released after the coronation of Shahuji as the next king. Yesubai, Sambhaji’s widow, requested the release of Rajaram and asked him to be made the Regent. Rajaram was declared the next king-in-waiting in 1681 by the Maratha ministers, who felt the need for immediate succession after Queen Yesubai and young Shahu ji were taken captive by the Mughals in 1689 after Raigad fell.

Rajaram’s reign was marked by constant warfare against the Mughal Empire, which had a strong presence in the region at the time. Rajaram had to resort to guerrilla tactics and warfare to fend off the Mughal forces. In 1689 itself, Rajaram was forced to flee his capital of Raigad and take refuge in the southern fortress of Ginjee, where he continued to lead the Maratha resistance against the Mughals.

Tarabai Bhosale (1675–1761), emerged as a crucial figure after this period. She was a prominent Maratha queen, regent (see Kolhapur for more), and warrior who played a crucial role in the Maratha resistance against the Mughal Empire after the death of her husband, Chhatrapati Rajaram Maharaj in 1700. Under her leadership, the Marathas were able to maintain control over their territories and harass the Mughal troops.

After Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, Shahu was released by the 7th Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah I (1707 to 1712). A civil war broke out between him and Tarabai, leading to Tarabai’s defeat in 1707 and retreat to Kolhapur. By 1710, the Maratha kingdom had split into two: Satara and Kolhapur.

Battle of Khed 1707

The Battle of Khed (1707) (in present-day Khed taluka in the district) was a significant conflict between Shahu Maharaj and the forces of Tarabai as part of the power struggle. This battle played a crucial role in Shahu’s rise to power.

In 1707 when Shahu ji sought to reclaim his position as the rightful leader of the Marathas, he faced strong opposition from Tarabai, the widow of Rajaram, who ruled as regent for her son, Shivaji II, from Kolhapur. The battle took place at Khed, a village 22 miles north of Pune, where Shahu, with the support of Maratha general Dhanaji Jadhav, confronted Tarabai’s forces. It is argued that initially, Jadhav was aligned with Tarabai, but during the battle, he switched allegiance to Shahu, significantly weakening Tarabai’s army. Shahu emerged victorious, securing Pune and Satara as his power base, while Tarabai retreated to Kolhapur, where she continued to rule independently. This battle not only established Shahu as the undisputed leader of the Marathas.

Tarabai and Shivaji II were soon overthrown by Rajasbai (second wife of Rajaram), who placed her son Sambhaji I (1698–1760 CE) on the Kolhapur throne. The conflict between the two seats of Maratha power concluded with the Treaty of Warna (1731), which recognized Kolhapur’s autonomy but kept it as a vassal of Satara.

This conflict laid the foundation for the rise of the Peshwa system, as Shahu later appointed Balaji Vishwanath (1662-1720) as his Peshwa.

Shift in Revenue policy

One of the important shifts that was taken during his reign was granting of chauth and sardeshmukhi rights to nobles. It was a significant shift in policy from the centralized system established by his father, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj who strictly controlled the granting of chauth and sardeshmukhi rights, retaining these financial privileges under royal control.

Chauth was tax levied amounting to 25% of the revenue or produce, collected from territories under their protection but not directly controlled by them. It was essentially a protection fee, where those who paid it were safeguarded from Maratha raids. Whereas, Sardeshmukhi was an additional 10% tax levied on top of the chauth, claimed as a hereditary right by the Marathas, considering themselves the rightful Sardeshmukhs (overlords) of the Deccan region. Only state-appointed officials were allowed to collect these revenues, which helped maintain centralized authority and prevented powerful nobles from becoming too independent.

Under Rajaram, granting the right to collect these taxes were given to regional nobles and chiefs which is argued to be an attempt to secure the loyalty of powerful commanders and local leaders. Also attempted to allow independent military action by local leaders without waiting for orders from the central administration. This decentralization allowed the emergence of powerful noble families, particularly the Peshwas, who later became the de facto rulers of the Maratha Empire. It laid the foundation for the Maratha Confederacy system, where different Maratha chiefs like the Scindias, Holkars, Gaekwads, and Bhonsales operated semi-independently but remained loyal to the central authority of the Chhatrapati.

Shaniwar Wada as the Seat of the Peshwas

Shaniwar Wada is a historically significant fortification located in Shaniwar Peth, Pune city. It served as the political and administrative center of the Maratha Empire and was the official residence of the Peshwas (prime ministers) who governed the empire under the nominal authority of the Chhatrapati from 1732 until the fall of the Marathas in 1818.

One cannot isolate Pune’s history from the influence of the Peshwas. Pune is known to have been expanded and diversified by the Peshwas. Some estimates say that the city rose from 25,000 residents to about 1 lakh residents within just a decade and 12 new peths (urban neighbourhoods) were created during this period. Many mandirs were also built during this period.

The Peshwa (Prime Minister) became the real power behind the throne during Shahu I’s reign who ruled from Satara. It was in 1713, Shahu appointed Balaji Vishwanath as the Peshwa, giving him considerable authority. Under Balaji Vishwanath and later Baji Rao I, the Peshwas expanded the Maratha Empire beyond Maharashtra into Malwa, Gujarat, Bundelkhand, and even Delhi.

Peshwa Baji Rao I, laid the ceremonial foundation of his residence on Saturday, 10 January 1730. The structure was named Shaniwar Wada, derived from the Marathi words "Shaniwar" (Saturday) and "Wada" (a term for a residential complex). The construction was completed in 1732 at a total cost of ₹16,110, a significant amount at that time.

The structure was originally intended to be built entirely of stone. However, after the completion of the first floor, people from Satara objected, claiming that only the Chhatrapati had the authority to commission stone monuments, not the Peshwas. In response, Chhatrapati Shahu I sent an official order to the Peshwas, stating that the rest of the building had to be constructed using brick instead of stone.

In 1773 Narayanrao, the fifth and ruling Peshwa, was brutally assassinated within the fort’s confines. The tragic twist? It is believed that the attack was orchestrated by his own family—his ambitious uncle, Raghunathrao, and his aunt, Anandibai. The echoes of his final moments are said to linger in the halls of Shaniwar Wada. It is believed that, on nights when the full moon bathes the fort in silver light, anguished cries of "Kaka mala vachava" (Uncle, save me) are still heard, a chilling reminder of his desperate pleas for mercy.

Shaniwarwada, was argued to have been destroyed by repeated fires in the early 20th century. Now only the fortified walls of the palace and a strong gate with spikes for security remain. The 1827 fire was believed to have destroyed the upper two floors of the palace, while the Royal Hall was destroyed in a fire in another fire in 1913.

In 1918, all this devastation was taken to a new level when it was attacked by the British, who destroyed all the upper floors. Another fire gutted the palace in 1928, this time lasting a week and destroying the entire structure. Even before this destruction, the status of Shaniwarwada was gradually deteriorating under British rule. After taking over, the British used the vast building for the Collector's office. Later, the ground floor was used as a prison and the upper floors housed a dispensary and a lunatic asylum.

Balaji Vishvanath Bhat, first Peshwa (1662-1720)

Balaji Vishvanath was the founder of the Peshwas of Pune. During the reign of Chhatrapati Sambhaji, he defeated the Maratha navy chief, Kanhoji Angria, when he was planning to attack Satara and convinced him to become a Shahu loyalist. For this bravery, he was made the Peshwa. He also rescued Pant Sachiv (also known as Gandekar, the rulers of Bhor) for which he was granted the rights of Pant Sachiv in Purandar as well as the fort. He reduced land leases that encouraged farming in the region. Balaji built strong relations with the court in Delhi and was able to receive grants for one-fourth of the revenue for Hyderabad, Bijapur, Tanjore, Tiruchirappalli, and Mysore, and Sardeshmukhi (one-tenth of the Deccan revenue). In addition, he received a grant for swaraj by Marathas for 16 districts that were identified as ruled by Shivaji. Balaji was also rewarded for his timely aid by the means of jagir. In 1734, Balaji acquired the Malwa region and the area between Chambal and Narmada while his brother was successful in usurping north Konkan from the Portuguese.

Bajirao Peshwa, Second Peshwa (1700-1740)

Bajirao Peshwa is probably the most well-known Peshwa. He is also known as Bajirao I or Bajirao Ballal. He was granted the Peshwai 7 months after his father’s death. He wanted to expand the Maratha kingdom up to the Northern part of India and is famous for fighting the Battle of Bhopal and the Battle of Delhi. He is known to have spread Maratha supremacy to the north and the south.

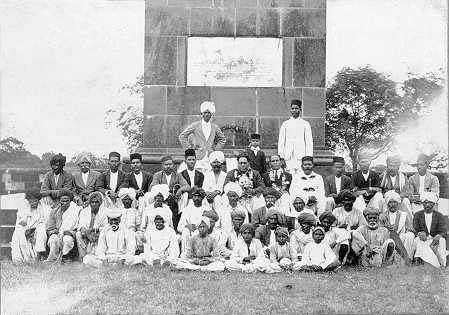

Plaque detailing “Family tree of Peshwas”. Source CKA Archives

The Gazetteer (1885), mentions how the practice of Dakshinas or money gifts was started by him. His triumph over the Maratha Senapati Trimbak Rao Dabhade alienated him from others. Hence, he continued with the customs started by Trimbak Rao that included dakshinas, where he fed thousands of Brahmins for many days, and also donated money.

He is also known to have moved his base from Saswad (part of present Pune district) to Pune city in 1728, and is responsible for laying the foundation of Kasba. During the time, Pune was already a well established town, with six peths. He saw Pune as a town for potential growth and began constructing the Shaniwar Wada making Pune new centre of power and the permanent headquarters of the Peshwas.

From when Bajirao made Pune the capital of the Peshwas, till when the British took over in 1818, the fortunes of the city were very closely linked to the fortunes of the Peshwas, thus, making it a very political city during the period.

Shahu Maharaj died in 1749 without an heir, his adopted son Rajaram II was placed on the throne though virtually the empire was under the control of the Peshwa, Balaji Baji Rao (1720 – 1761). The Peshwas continued to rule in the name of the Satara Chhatrapati, but the Chhatrapati had no real power after Shahu’s death. The Maratha Empire expanded across India, becoming the dominant power in the 18th century under the Peshwa rule.

Battle of Wadgaon/Vadgaon, 1779

The Battle of Wadgaon (12–13 January 1779) was fought near Wadgaon Maval in present-day Pune district and formed a key episode in the First Anglo-Maratha War (1775–1782).

The war stemmed from a succession dispute over the Peshwa’s position in the Maratha Empire. The British East India Company backed Raghunathrao (Raghoba) in his bid to replace the young Peshwa Madhavrao II, launching a military campaign into Maratha territory. British forces under Colonels Egerton and Cockburn advanced toward Pune, aiming to seize control, while Maratha commanders Mahadji Shinde and Tukoji Rao Holkar countered with swift cavalry raids and guerrilla tactics that severed British supply lines.

Harassed along trade routes, the British retreated to Talegaon, only to be surrounded by Maratha forces. Employing a scorched-earth strategy—evacuating villages, destroying crops, removing food stores, and contaminating wells—the Marathas worsened British shortages. Weakened and under constant attack, the British attempted to withdraw but were ambushed near Wadgaon, suffering heavy losses. Forced to surrender, they signed the Treaty of Wadgaon, agreeing to return all territory acquired since 1773.

However, Governor-General Warren Hastings rejected the treaty, claiming the British officers at Wadgaon lacked authority to sign it. Declaring it void, he ordered the resumption of hostilities to protect Company interests in western India.

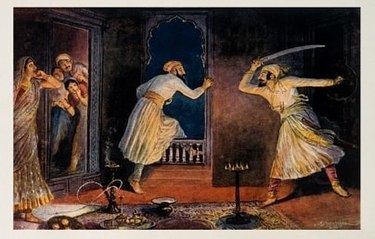

A mural illustrating the British surrender during the First Anglo-Maratha War. This artwork is part of the Victory Memorial (Vijay Stambh) situated at Vadgaon Maval. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Poona Plunder, 1797

The Poona Plunder of 1797 arose from fierce internal rivalries within the Maratha leadership, particularly between Peshwa Bajirao II, Daulat Rao Scindia, and statesman Nana Phadnavis, during a period of overall Maratha decline that paved the way for British interference.

Following the death of Peshwa Madhavrao II Narayan in 1796, Bajirao II (son of Raghunathrao) sought the Peshwa’s seat but faced strong resistance from Nana Phadnavis and other Maratha nobles. At the same time, Scindia, a dominant power in Pune politics, aimed to control the administration. According to the Bombay Gazetteer (1885), to fund Scindia’s military campaigns, his associate Ghate led a ruthless plunder of Pune—arresting and torturing merchants, bankers, and wealthy citizens to extort money. Relatives of Nana Phadnavis were tied to cannons, and properties of prominent residents were seized.

Bajirao II is believed to have tolerated the plunder, as it weakened his political opponents. His brother Amritrao supported Scindia’s faction, deepening the chaos. The city suffered widespread devastation, and the event’s long-term consequence was to undermine Maratha unity, enabling the British to exploit the situation—culminating in the Treaty of Bassein (1802).

Battle of Poona, 1802

The Battle of Poona (1802) was a decisive clash between Yashwantrao Holkar and Peshwa Bajirao II, ending in Holkar’s victory and forcing Bajirao II to seek British protection. This led to the Treaty of Bassein (1802), which marked the beginning of British dominance over the Marathas.

Fought during Diwali on Pune’s eastern outskirts—at Ghorpadi, Banwadi (modern-day Wanowrie), and Hadapsar—Holkar is said to have instructed his troops not to attack until 25 enemy cannon shots were fired. Once the signal came, his forces launched a swift, coordinated assault, defeating Bajirao II. Notably, Holkar forbade harm to civilians, reflecting his disciplined command.

After taking Pune, Holkar assumed control of the administration, freeing political prisoners such as Moroba Phadnavis (brother of Nana Phadnavis) and Phadke, installing Amrutrao as Peshwa, and then departing for Indore on 13 March 1803, leaving 10,000 troops to maintain order.

The Poona Plunder, 1802

The second Poona Plunder took place in 1802, following Yashwantrao Holkar’s victory over Bajirao II in the Battle of Poona (25 October 1802). The looting was reportedly as severe as the 1797 plunder by Scindia, with wealthy residents tortured for money. Before the battle, Bajirao II had stationed guards to prevent people from fleeing Pune, trapping them for the aftermath.

After the victory, Holkar’s troops continued the plunder, while British involvement loomed in the background—Colonel Close, a British representative, was in Pune at the time. Both Amritrao and Holkar are believed to have wanted him to remain, as his presence was seen as a sign of British approval.

Famine, 1802

Amidst the rivalry of Holkar and Shinde (Scindia), Pune was hit with an overwhelming famine in 1802-03. Grains had to be imported, but this didn’t help the situation. There was a lot of outmigration from the district, where people fled to either Gujarat or Konkan. Many people also died of hunger. The government at the time tried to reduce the hardships by reducing taxes, and primarily only taxed the rich. During this time, the city’s population reduced from 1,50,000 to 1,13,000. Many songs and poems were written about the situation of Pune during the time.

Restoration of Baji Rao II

On 27 October 1802, after the Holkars captured Pune and installed Amrut Rao as Peshwa, Bajirao II fled to Raigad, where he remained for about a month. Sensing an opportunity, the British offered him protection in exchange for signing a subsidiary treaty. On 1 December 1802, he sailed to Bassein (Vasai) aboard the Harkuyan. Bajirao hesitated, as several Maratha sardars—such as Panse and Purandhare—urged him to negotiate with Holkar instead. Even his brother, Chimnaji, opposed an alliance with the British.

Nevertheless, under pressure, Bajirao signed the Treaty of Bassein on 31 December 1802, effectively surrendering Maratha sovereignty. The treaty made the British the dominant power in the Deccan and reduced the Peshwa to a puppet ruler. Its terms required that the British station a subsidiary force in Pune, that Bajirao refrain from forming alliances without their consent, and that he maintain only a British-approved army.

According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1885), General Arthur Wellesley marched from Mysore in March 1803 to restore Bajirao II. After crossing the Krishna River on 12 March, his forces were welcomed by the Patwardhans and other Maratha factions loyal to Bajirao. On 19 April, Wellesley learned that Amrutrao might burn Pune before retreating, prompting a rapid advance through the Bor Pass—covering 60 miles in 32 hours. Wellesley reached Pune on 20 April, scattering Holkar’s remaining forces. Finally, on 13 May 1803, British troops escorted Bajirao II from Panvel back to Pune, reinstating him under their protection.

Colonial Period

The British presence in Pune had started increasing since 1792, with the arrival of Sir Charles Warre Malet (1752–1815). He was a British diplomat, historian, and political officer in India, serving under the British East India Company. He played a crucial role in shaping British diplomatic relations with the Maratha Empire during the late 18th century.

He is believed to have built the Residency at Sangam (near present day Bund Garden). Malet also started building some bungalows there, of which some still exist. These are one of many spectacular examples of colonial architecture in the city till date. In 1790, with the help of Malet, a treaty was signed between the Marathas and the British against Tipu Sultan of Mysore. Malet’s importance in Pune started increasing and many Europeans slowly started settling in the city.

Interestingly, the Sangam is also known to have introduced better medicine in the city. The district was often ravaged with diseases such as small pox. 1806 saw the introduction of vaccination in the district through a colonial doctor known as Dr. Coats. This was the time during which smallpox was almost entirely eradicated from the city and its surroundings.

Treaty of Poona, 13 June 1817

The Treaty of Poona was signed on 13 June 1817, between the British East India Company and Shrimant Peshwa Baji Rao II. It was an important agreement that significantly reduced Maratha control and increased British control over Maratha territories. The treaty was signed shortly before the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818).

Peshwa Baji Rao II had previously signed the Treaty of Bassein (1802), which made him a client ruler under British protection, effectively reducing his autonomy. Growing discontent among the Marathas led to tension between the Peshwa and the British. The treaty was signed following rising hostilities and political instability within the Maratha Confederacy, especially the rivalry between the Peshwa and other Maratha chiefs, like Yashwantrao Holkar and Daulat Rao Scindia.

The treaty resulted in Peshwa ceding several territories to the British East India Company as compensation for the British military support. This included significant areas around Poona (modern-day Pune) and regions extending towards Ahmednagar. This treaty gave British control of territory north of Tungabhandra and south of the Narmada River.

Additionally, the treaty curtailed the authority of the Peshwa, restricting his ability to form alliances or wage war without British approval. The British gained control over the external affairs of the Maratha Empire. The Peshwa was required to maintain a British force in his territory and pay for its upkeep, effectively enforcing the subsidiary alliance system initiated by Lord Wellesley.

Monstuart Elphinstone who served as the Resident at the Court of Peshwa Baji Rao II in Pune before he became Governor of Bombay (1819–1827) drafted the Poona Treaty, which Bajirao signed on 13 June 1817. In addition to the lands he gave up, Bajirao agreed to receive a yearly payment as a settlement of all of his claims on the Gaikwad. Bajirao also disbanded some of his horses. The regular battalions of the Peshwa were moved as part of the army that the British were required to maintain in exchange for the new territorial grant. Only one battalion, led by a colonial military officer Captain Ford, was preserved in Peshwa service, and the English created a new corps in their place. When the terms of the Treaty of Poona were modified in July 1817, Bajirao departed Pune for his yearly pilgrimage to Pandharpur.

The Treaty of Poona was a critical step in the gradual dismantling of the Maratha Empire and the consolidation of British power in India. It diminished the political autonomy of the Peshwa and set the stage for the final defeat of the Marathas in the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818).

Battle of Kirkee, 5 November 1817

The Battle of Kirkee (now known as Khadki), is probably one of the most important events in Pune’s history. This battle ended the Peshwai rule in the area and established British rule. The Battle of Khadki (also spelled Khirkee or Kirkee) took place on 5 November 1817 at present Khadki in Pune. This battle was fought between the forces of the British East India Company and Peshwa Baji Rao II during the early stages of the Third Anglo-Maratha War. Led by Mountstuart Elphinstone, the British decisively defeated the Maratha forces, forcing Baji Rao II to flee Pune. This defeat allowed the British to take control of Pune and install Pratap Singh, a descendant of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, as a nominal ruler under British oversight.

The Surrender of Pune to the British in 1817

The day before, the district was given up, order and calm were quickly established, and utmost care was taken to protect the peaceful town residents. On 22 November General Smith chased Bajirao to Mahuli in Satara, then to Pandharpur and finally to Junnar, where Bajirao hoped Trimbakji would hide him amid the hills. In search of protection towards the end of December, Bajirao fled south toward Pune. Upon learning that the Peshwa intended to attack the city, Colonial Officer Colonel Burr, who was in charge of Pune, sent for assistance and soon another battle was going to take place between the British and the Marathas. The second and the final battle between the two factions was fought at Koregaon in January 1818. In this battle, the British loss was 175 men killed and wounded as opposed to the Maratha loss of 500 or 600 men.

Battle of Koregaon, 1 January 1818

The Battle of Koregaon was another significant conflict fought on 1 January 1818, between the forces of the British East India Company and the Maratha Empire. It was part of the Third Anglo-Maratha War and took place near the village of Koregaon Bhima (not to be confused with Koregaon Park) of Shirur Taluka , on the banks of the Bhima River in the district.

During the Third Anglo-Maratha War, Peshwa Baji Rao II sought to reclaim lost influence and power from the British by mobilizing his forces against the British. According to the Gazetteer of Bombay Presidency (1885), a force of around 800 British troops (including 500 soldiers from the Mahar Regiment) marched to defend the garrison at Koregaon. The Maratha army, numbering around 30,000 and led by Peshwa Baji Rao II, launched an attack on the British contingent stationed at Koregaon. On reaching the high ground above Koregaon Bhima, about 10 in the morning of 1 January, the Company army saw Martha forces on the eastern bank of the Bhima.

Captain Francis Staunton, a British officer, continued his march and took possession of the mud-walled village of Koregaon. When the Marathas caught sight of the British troops, they recalled a body of 5000 infantry some distance ahead. The infantry soon arrived and formed a storming force divided into three parties of 600 each. The storming parties breached the wall in several places, especially in the east, forced their way into the village, and gained a strong position inside the walls. Still, despite the heat, thirst, and terrible loss, the besieged held on till evening, when the firing ceased, and the Peshwa's troops withdrew. The following day, Captain Staunton retired to Sirur. His loss was 175 men killed and wounded, including twenty-one of the twenty-four European artillerymen. About one-third of the auxiliary horses were killed, damaged, or missing. The Marathas lost five or six hundred men.

Today, the battle is commemorated annually by members of the Dalit community, including followers of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who saw the event as a turning point in the fight against caste discrimination. The anniversary of the battle, known as Koregaon Bhima Shaurya Din, draws thousands to the memorial each year.

Colonial Administration

The British acquired the district between 1817 and 1868, primarily through conquest, treaties, and exchanges with Indian rulers. In 1817, the British seized control over most of Pune following the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-1818), which led to the overthrow of the Peshwa. This victory marked the end of Maratha sovereignty and paved the way for British dominance in western India. Over the next few decades, various Maratha rulers ceded territories to the British, either due to political pressure or in exchange for other lands. On April 20, 1844, following the death of the Chief of Kolaba, the British annexed half of the village of Chakan in Khed, further expanding their control in the region.

The process continued in 1861, when Scindia of Gwalior signed a treaty on 12 December 1860, transferring 12 villages to the British. These included three villages in Sirur, seven in Bhimthadi, and two in Haveli, marking yet another shift in power. Five years later, in 1866, the Gaikwad of Baroda ceded additional land on 9 October 1866, including half of Chakan village in Khed and one more village in Haveli.

By 1868, the Holkar ruler of Indore also surrendered six more villages to the British on November 28, 1868, further consolidating British authority. These included one village in Junnar, four in Khed, and one in Sirur. Through these successive agreements, the British systematically absorbed more of Pune’s territory, turning what was once the heartland of the Maratha Empire into a key part of British India.

Revenue System

According to the Gazetteer (1885), before British rule, the revenue system in Pune was based on the Jatha (or Thai) system, which functioned as a family estate-based settlement system. The land was originally owned collectively by families, and each family was responsible for paying its share of revenue. It is said that each settlement or village had designated family holdings known as thals, named after the occupant's surname. The head of the family estate (or Jatha) was responsible for collecting and paying revenue on behalf of the entire estate. These estates were passed down hereditarily and governed by Hindu inheritance laws.

The village headman (mukaddam or patil) played a significant role in revenue administration. The headman collected revenue from individual family estates and paid the government’s share. In times of financial hardship or government demand, the entire family estate was collectively responsible for any defaults.

Under Malik Ambar, instead of payments in kind (crops), Malik Ambar introduced a fixed cash revenue system resulting in a major reform in land revenue. During his rule, Land was measured and classified based on its fertility and quality, and revenue was determined accordingly. This system, which was said to be inspired by Todar Mal's settlement reforms, created a more systematic approach to taxation. Shivaji refused to make such payments for his father's estates (discussed above).

After the British takeover in 1817, the revenue system underwent further transformation. Fixed land revenue rates were established, often favoring British economic interests. The British expanded ryotwari settlements, where individual cultivators (ryots) were directly responsible for paying revenue to the government, reducing the role of traditional headmen. According to these reforms villages were surveyed and taxed based on productivity, with certain lands (such as waste or inam lands) exempted or taxed differently. The British system often increased the tax burden on farmers, leading to peasant unrest and periodic revolts.

Ramoshis of Pune

The Ramoshis of south Pune rose in revolt in 1826, due to the reduction in the local garrison. They were so successful and enterprising under the revolutionary Umaji Naik that, in 1827, when they could not be put down, their crimes were pardoned. They were put to work as hill police, paid for their crimes, and given land grants. The Ramoshis' triumph sparked a revolt among the Kolis of the northwestern Pune and Ahmednagar hills. In Pune, Thane, and Ahilyanagar, sizable gangs turned to outlawry and caused a lot of trouble. As a result, strong troop detachments were recruited from all the surrounding areas. By 1830, the rebel bands had been broken up, their commanders had been apprehended, and order had been reinstated.

Koli Uprising

Between 1839 and 1846, hill “tribal” uprisings caused the following significant disruptions. Early in 1839, Koli communities broke out in several regions of the Sahyadris and raided and pillaged several settlements. Under the leadership of three individuals, Bhau Khare, Chimnaji Jadhav, and Nana Darbare. The number of participants quickly increased to three or four hundred. The uprising leaders claimed to be working on behalf of the Peshwa and took control of the government in his name, giving the uprising a political bent. The Brahmins convinced the populace that most British troops had evacuated the area because the Pune garrison had recently undergone significant reductions. The British acted quickly to avert considerable trouble. They assembled a group of messengers and locals and suppressed them throughout the night with continuous attacks. The rising ended as soon as the main band dissolved and the members were identified fully. Of the 54 rebels convicted, a Brahmin named Ramchandra Ganesh Gore and a Koli were executed. At the same time, the other twenty-four received pardons or were found not guilty. Of the other rebels, some received life sentences of transportation and others received varying prison sentences.

In 1844, another uprising took place in Pune under the leadership of Raghu Bhangria's. They ambushed a native police officer, and holed up ten constables in the hills and killed all except three. The disturbances began in Satara and moved south through Purandhar in 1845, affecting the area south of Pune. Sixty-two Ramoshis were added to the Pune police force. On 18 August 1845, Bapu Bhangria was apprehended after a fight with one of his men. Despite the death of their commander, the gangs carried on harassing the nation and pillaging communities with the covert assistance of some influential people. The atrocities committed were widespread. A writer in the Purandhar mamlatdar's establishment was assassinated, government funds were seized as they were being gathered, a Patil was killed because he had assisted the police in finding some previous outrage, numerous moneylenders were looted, one or two of whom were also maimed.

The First War of Independence, 1857

Nanasaheb Peshwa, who was the adopted son of Bajirao (Bajirao II), took an active part in the fight and joined the freedom fighters where he wanted his right as the Peshwa to be restored. Pune was free of overt acts of revolt during the 1857 Revolt, including offences that called for political charges. For attempting to cause a disturbance in the city of Pune in June 1857, a constable who had been discharged received a whipping. Later that year, Nural Huda, a maulvi from Pune and one of the leaders of the Wahabi sect of Muslims in Western India, was imprisoned at Thane on charges of maintaining a treasonous correspondence with the Muslims from Belgaum and Kolhapur who had joined the revolt. A few suspicious Northern Indians were compelled to return home. The Kolis and other hill tribes assaulted a few settlements and pillaged their longtime enemies, the moneylenders. For printing a seditious declaration in support of Nana Saheb, the late Peshwa's adopted son, a man was charged and executed in 1858. In Pune, a seditious paper was posted in September 1857 close to the college and library. The dangerous elements in Pune were overwhelmed by the garrison due to the local authorities' vigilant watch.

Struggle for Independence

The district's involvement in the freedom movement dates back to the 19th century when social reformer Jyotirao Phule founded the Satyashodhak Samaj, an organisation that worked towards the upliftment of marginalised communities and women's education. The Samaj's work was carried on by other reformers such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who founded the Servants of India Society to work for the betterment of the country.

During the early 20th century, Pune became a centre of revolutionary activity, with leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and Mahatma Gandhi inspiring the fight for independence. Tilak's fiery speeches and nationalist writings, which called for Swaraj or self-rule, inspired a generation of young revolutionaries who saw him as a hero and mentor.

Chitrashala Steam Press

Many new initiatives were taken up by the revolutionaries in Pune too during this time. Among them, Vishnu Krishna Chiplunkar, an Indian Freedom Fighter established the Chitrashala Press in Pune in 1878. The vision behind this endeavour was to encourage fine arts and take Chiplunkar’s anti-colonial agenda forward. This steam press played an extremely crucial role in India’s Independence Movement.

It aimed to spur nationalism in the country by printing images of historical figures and some loose symbols that would promote subversive political ideas. For example, the images of Khandoba, the Warrior Bhagwan sitting on horseback with a sword in his hand to slay demons, Ram’s mother freeing a caged parrot, or postcard images of uncaged birds. The press also went on to publish commercially successful lithographs like Rampanchayatam and Shivpanchayatam and other hundreds of large, colourful lithographs. Due to its anti-British political agenda, Chitrashala played an important role in spreading revolutionary ideas indirectly through mass-produced artworks that remain outstanding.

Kaal Newspaper

Shivram Mahadev Paranjape, founded the weekly extraordinaire Kaal in 1897. To channelize his patriotism, he founded the weekly, Kaal, and in a brisk period, Kaal became immensely popular, addressing issues ranging from social, political, historical, religious to literary. Kaal (The Times) had ushered in a new era of satirical and incisive writing. Indicted on charges of sedition due to his writings in Kaal, in 1908, Paranjape was sentenced to 19 months of imprisonment which, however, ended after 15 months. Upon failing to pay the bail amount of Rs. 10,000 the government seized 10 volumes of published writings that formed the soul of Kaal between 1900-1908. Kaal, thus met with its fateful demise. Later, “Kaal karta” Paranjape founded the weekly Swarajya in 1920-21.

Mulshi Satyagraha

The Satyagraha Movement launched by Gandhi in 1919 took various forms throughout India. In the district, the movement manifested in the form of revolt against the construction of a Dam in Mulsi Peta. Concerned that this dam will destroy their way of life, the peasants of the region launched the anti-dam struggle now famous as the Mulshi Satyagraha. Gandhiji, who toured Pune in 1920, advised the peasants to offer satyagraha at the site of the construction rather than petition the government. Thus, the campaign was launched under the leadership of the prominent nationalist Senapati Bapat. The efforts of the British District Collector to convince peasants of the benefits of the dam were disregarded, as the sacrifice of their land and home for the sake of the rich people was unacceptable to them. Bapat and young leaders like Shankar Rao Deo toured all over Maharashtra to raise funds for the struggle, and prominent nationalists such as S.M. Paranjape and Sarojini Naidu gave their support to the peasant struggle. Bapat successfully compelled the colonial government to offer compensation to the peasants in exchange for their land.

The Mulshi Satyagraha eventually ended when Senapati Bapat and other leaders were arrested by the British police. However, this struggle played a crucial role in deepening the roots of national movement among the masses and drawing the peasantry into the mainstream of the freedom struggle.

Electricity in Pune

Electricity was first introduced in the city in 1920, by the British. Hydroelectric plants were set up in the Western Ghats between Pune and Mumbai in the first few years of the 1900s.

The Paisa Fund and Swadeshi Movement

In order to promote indigenous production, The ‘Paisa Fund’ was established in 1905 by Antaji Damodar Kale along with Bal Gangadhar Tilak. The objective of this was to support Swadeshi industries and fight recurrent famines brought on by reliance on agriculture. In Talegaon, a glass plant was instituted in 1908 and it began producing glass in August 1908. Overtime, the production of this factory increased to such a level that 60% of India's glass demand was met by it during World War I, having an effect on glass imports. The Paisa Fund movement played an unrivalled role in India’s Independence by supporting industrialization, encouraging Swadeshi industries, and offering technical training.

Handmade Paper Institute

Further bolstering the Swadeshi Movement in India, the Handmade Paper Institute was established in the year 1940. The factory was established under the guidance of K.B. Joshi, a pioneer of paper manufacture in India. Joshi was a firm believer in the swadeshi ideal espoused by Mahatma Gandhi. Like the Glass factory, it also provided employment to the local population. It is noteworthy that the Handmade Paper Institute had the distinction of supplying the paper on which the very first copies of the Indian Constitution were published. The Institute continues to function even today, and produces paper in an entirely eco-friendly manner, with cotton rags rather than wood pulp.

Post-Independence

After Independence, initially, the district was part of the larger Bombay State. However, due to the Samyukta Maharashtra Movement, which demanded a separate Marathi-speaking state, Bombay State was reorganized on 1 May 1960, leading to the creation of Maharashtra and Gujarat. The district then officially became part of Maharashtra. When the British left after Indian independence, the bungalows that were vacated were said to have been occupied by all the communities who were known to have close connections with the British in the district.

Two events in the 1960s are important in Pune’s history. One of them is the establishment of Pimpri Chinchwad (the new industrial township), and second were the disastrous floods of 1961. Panshet dam (also known as Tanajisagar dam on the Ambi river), built on the Ambi River, a tributary of the Mutha River, was constructed in the late 1950s. It was primarily designed for irrigation purposes. Along with Varasgaon, Temghar, and Khadakwasla dams. The dam plays a crucial role in supplying drinking water to Pune, making it an essential component of the city's water management system. In 1961, the dam burst in the first year of its construction completion. This affected a large part of the western side of Pune, which at the time was the largest urban sprawl in the city.

Sources

"Why bells from Portuguese-era churches ring in temples across Maharashtra". 22 December 2018.https://www.hindustantimes.com/more-lifestyl…

.Lokmat News18. 12 February 2023.https://web.archive.org/web/20230816210511/h…

Aditi Dixit. 2024. ‘Naneghat – The Royal Mountain Pass’,Puratattva. Accessed on March 20, 2025.https://puratattva.in/naneghat-the-royal-mou…

Balkrishna Govind Gokhale. 1988.Poona in the Eighteenth Century: An Urban History.Oxford University Press.

BalKrishna. 1932.Shivaji the Great: Volume 1. D. B. Taraporevala Sons.

Campbell, James M ed. 1885. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona, Vol. XVIII, Pt. I. The Government Central Press, Bombay.

Chandrashekhar Shirur. 2020. ‘Unsung Warrior’,Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed on March 15, 2025.https://photocontest.smithsonianmag.com/phot…

Chinmay Damle. 2023.“Mahatma Phule’s Fight for Equitable Water in Pune.”Hindustan Times. Accessed 4 May 2025.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Drifter Advait. 2023. Bedse Caves. Drifter Advait.Accessed on April 11, 2025https://drifteradwait.com/bedse-caves/

Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency. 1885 (Reprinted in 1992, e-Book Edition 2006). Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency: Poona District, Vol XVIII.Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Himanshu Damle. 2023. Bedse Caves (aka Bedsa Leni), Bedse Village, Maval Taluka, Pune District, Maharashtra. Himanshu Damle.Accessed on April 11, 2025https://hdheritagewalks.wordpress.com/2023/0…

Incredible Temples. “Ekvira Mandir.”Instagram. Accessed 4 May 2025.https://www.instagram.com/incredible_temples…

Leo Patnaik. 2024. ‘The Haunting of Shaniwar Wada: Echoes of Betrayal and a Desperate Cry’,Folklore Chronicles. Accessed on March 17, 2025.https://folklorechronicles.com/the-haunting-…