Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient period

- Early Coastal Settlements at Gharapuri Island

- Traditional Accounts and the Antiquity of Chaul

- Satavahana Period & the Rise of Chaul as a Port

- Trade Networks and the Inland Port of Goregaon

- Satrap Influence in the Konkan

- The Mauryas of Konkan and the Question of Puri

- Chalukya Campaigns and the Western Ocean

- The Kalachuris and the Shaiva Excavation at Gharapuri

- Shilahara Rule and Commercial Governance at Chaul

- Alibag and the Bene Israel Settlements on the Raigad Coast

- Medieval Period

- The Bahmani Sultanate and the Contest for Chaul

- Portuguese Expansion and Rivalries on the Raigad Coast

- Korlai Fort and the Luso-Indian Speaking Village

- Siddis of Janjira and Murud

- Marathas

- Shivaji’s Naval Ambition on the Konkan Coast and Kolaba Fort

- Raigad as the Capital of the Maratha Empire

- Shivaji’s Rajyabhishek at Raigad, 1674

- The Siege of Raigad and Mughal Capture (1689)

- Angres of Kolaba, Kanhoji Angre and the Rise of a Maritime State

- Formalization of the Kolaba State

- Military Strength and Naval Strategy

- Clashes with European Powers

- Battle of Khandheri, 1718

- Cultural and Religious Patronage

- Economic Sovereignty

- Kanhoji’s Death and Samadhi (1731)

- Fracture and Rivalry Among the Angrias

- Raghuji Angre and Later Prosperity

- British Annexation of Kolaba (1793–1840)

- Colonial Period

- Expansion After the Maratha Wars

- District Formation and Growth

- The First War of Independence, 1857

- Acharya Vinoba Bhave and Bhoodan Movement

- Education and Print Culture

- Land Tenures and Agrarian Structure

- The Khot System

- Chavdar Tale and the Mahad Satyagraha (1927)

- V.B Shiledar and Chirner Jungle Satyagraha

- Post-Independence

- Renaming of the District

- Alibag’s White Onion

- Sources

RAIGAD

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

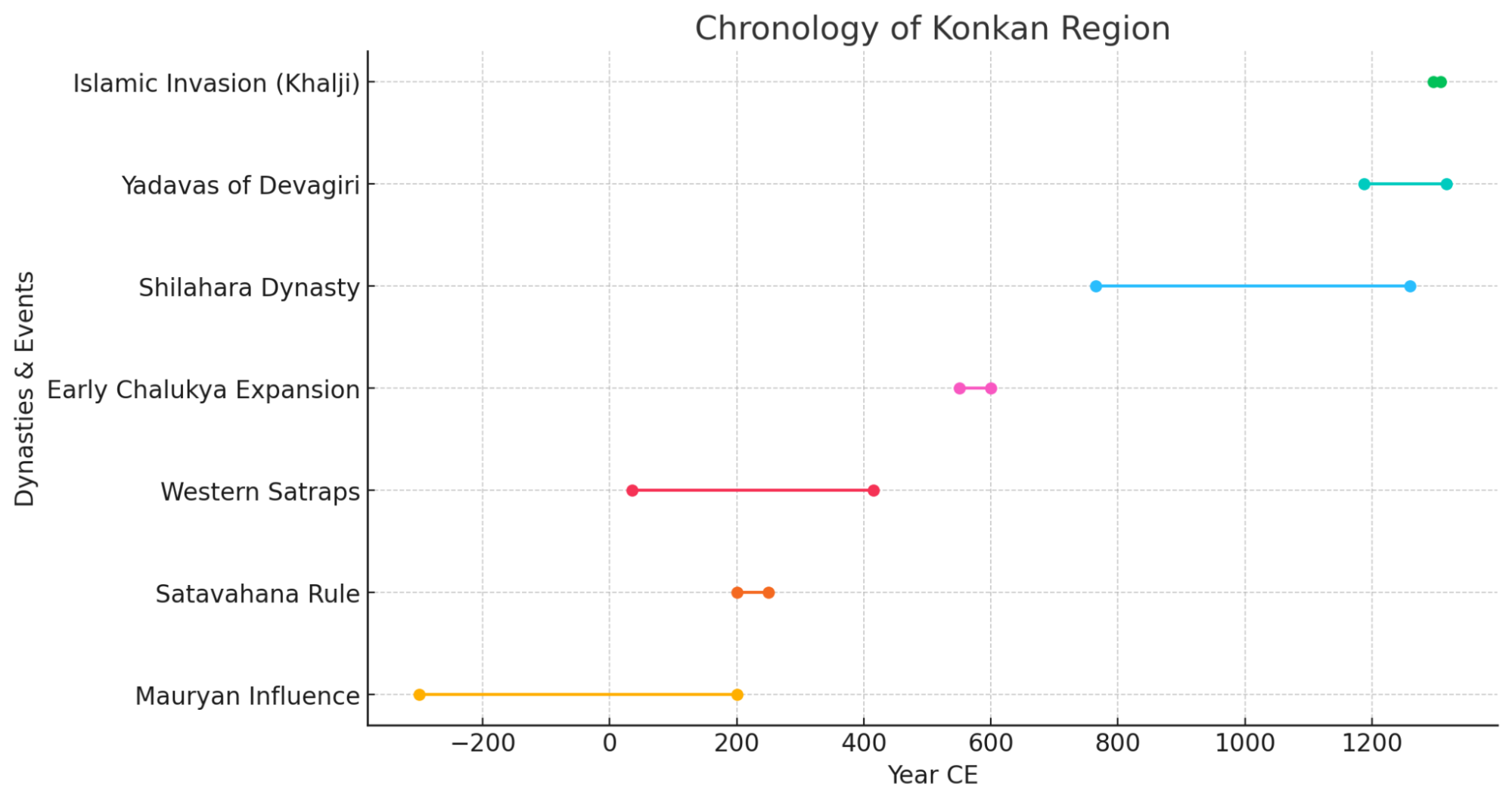

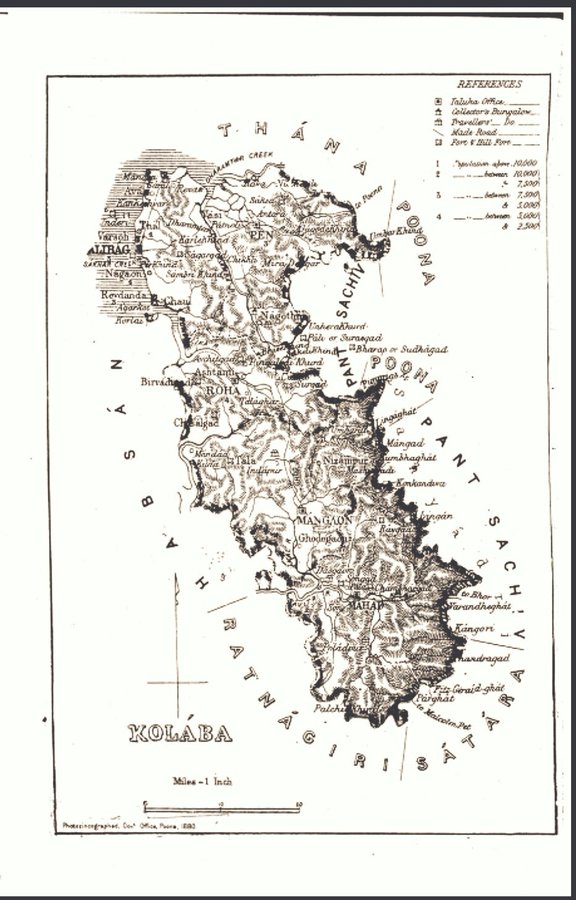

Raigad district, formerly known as Kolaba (not to be confused with Colaba of Mumbai City), is located within the Konkan division along the coastal belt. Bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west and the Sahyadri hills to the east, the district has long occupied a position of both geographic and strategic significance. The district’s coastal location, in many ways, made it a natural point of contact for maritime trade and cultural exchange. Ports such as Chaul were active from ancient times, and their presence is noted in early foreign accounts, including those of Ptolemy and the Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang.

In the course of its history, the district of Raigad came successively under the control of several political powers. The early medieval period saw the influence of regional Sultanates, followed by the advance of the Mughal Empire into the Konkan. With the arrival of European powers along the western coast, the Portuguese and later the British established varying degrees of presence and authority in the region. The district, however, occupies a special place in the history of the Maratha state. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, the hill-fort of Raigad was selected by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj as the seat of his newly established kingdom, and in 1674, it became the site of his rajyabhishek (coronation). In later years, it also became a prominent base for the Siddis and the Angres.

Etymology

The name Raigad is traditionally interpreted as a combination of rai or raja, meaning "king," and gad, meaning “fort” in Marathi. The term is commonly understood to refer to the hill-fort of Raigad, which served as the capital of Shivaji Maharaj’s kingdom and remains central to the district’s identity.

The earlier name of the district, Kolaba, is believed to derive from Kolabhat, a word in the dialect/language of the local Koli community. The term likely reflects the historical presence and association of the Koli people with the coastal forts and settlements of the region.

Ancient period

Early Coastal Settlements at Gharapuri Island

Among the earliest inhabited sites known in this region is the island of Gharapuri, situated off the northern coast of the present district. Long before the famed rock-cut shrines were excavated into its basalt outcrops, the island appears to have served as a port and halting station for vessels plying the western seaboard. Archaeological discoveries, including fragments of Roman amphorae and a brick stupa dated to the 2nd century BCE, indicate both commercial activity and Buddhist presence during this early phase. It is mentioned in the colonial district Gazetteer (1883) that during this time, the island may have served as a regional hub under local rulers. For its location at the mouth of Thane Creek rendered Gharapuri a favourable anchorage for ships seeking fresh water and shelter. Very notably, archaeologist Manish Rai (2014) observes that Gharapuri’s early prosperity derived not only from geography but from its ability to levy docking fees and serve as a regulated port under local chiefs. These maritime functions, in many ways, would come to ensure the island’s continuity in regional trade long before its religious monuments came to define its legacy.

Traditional Accounts and the Antiquity of Chaul

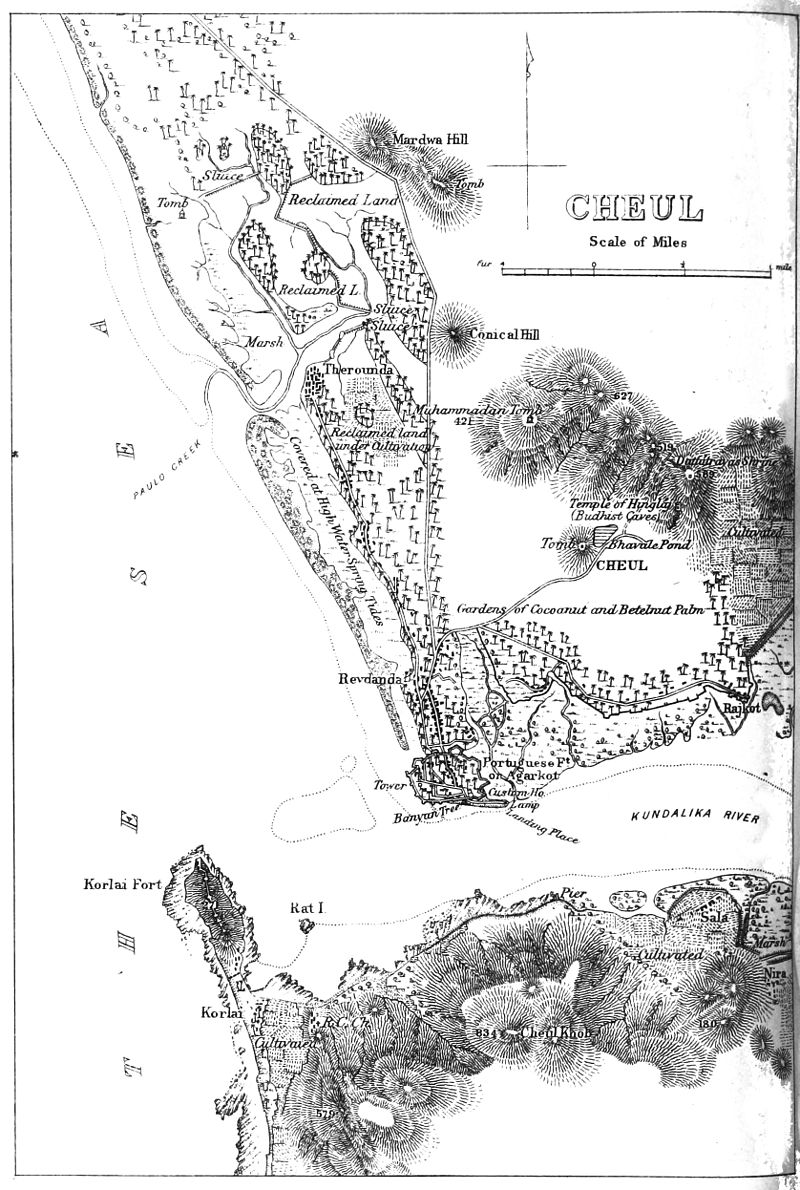

While Gharapuri anchored the district’s northern coastline, Chaul rose as its principal port to the south. Known in older traditions as Chainpavati and Revatikshetra, the town is remembered in local lore as an ancient seat of settlement dating back to the period of Krishna’s reign in Dwarka. Though such associations survive mainly in oral traditions, they point to the enduring antiquity ascribed to the site by the people of the Konkan.

Chaul, notably, came to occupy a prominent place in the early history of the region. Situated at the mouth of the Kundalika River and near strategic mountain passes, it served as a vital coastal hub for trade between the Deccan and the western seaboard. It emerged as the leading mart in Raigad’s ancient seaboard and drew the attention of both Indian rulers and foreign chroniclers.

Satavahana Period & the Rise of Chaul as a Port

By the opening centuries of the Common Era during what is known as the Satavahana period, Chaul had become one of the best-known ports on India’s western coast. The Roman naturalist Pliny, writing around 77 CE, refers to a harbour called Symulla, likely a Greek rendering of Chaul. Ptolemy, in the 2nd century CE, named a place called Timulla in the same region, which is believed to refer to Chaul too. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea refers to it as a significant emporium on the Konkan coast, engaged in the export of sesamum, spices, textiles, and steel, and in the import of wine, metalware, and fine cloth from Egypt, Arabia, and the Mediterranean.

Within the subcontinent, too, Chaul’s prominence was acknowledged. Inscriptions found in the Kanheri caves, dating from the 2nd to 5th centuries CE, mention donations from the goldsmiths and merchants of “Chemulaka”—the Prakrit rendering of Chaul. These records not only reveal the economic vitality of the port but also its connection with wider religious patronage networks, particularly those linked to Buddhism.

The goods that passed through Chaul moved inland via the Sahyadri passes, over routes that connected Raigad to the larger Deccan economy. In consequence, the town became a hinge between oceanic trade and plateau exchange, sustaining the district’s role in early regional commerce.

Trade Networks and the Inland Port of Goregaon

Not all of Raigad’s ancient trade moved through its coastal harbours. Inland settlements, too, played a part in sustaining commercial activity. Chief among these was Goregaon, formerly known as Ghodegaon, situated along the Kal River in present-day Mangaon taluka. The town’s name, combining ghode (horse) and gaon (village), has led many to believe that it was renowned in the horse trade. This connection has led some scholars to associate it with Hippokura, a settlement mentioned in Ptolemy’s Geographia.

Strategically positioned near the confluence of the Kal and Savitri rivers, Goregaon served as an inland port where goods descending from the Sahyadri hills could be transferred onward to coastal destinations. Its bustling market handled horses, textiles, metals, and provisions, allowing it to function as a secondary (yet crucial) node in the trading networks of ancient Raigad.

Satrap Influence in the Konkan

While Raigad’s ports and inland routes remained active through the early centuries of the Common Era, their fortunes were shaped by the broader power struggles across western India. Among the first northern powers to extend influence into the Konkan were the Western Satraps, also known as the Kshatrapas, whose Indo-Scythian rulers maintained dominion over parts of Gujarat, Malwa, and the western coast between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. Around 200 CE, the Satrap king Rudradaman I is recorded as having defeated a Satavahana ruler, establishing a foothold in the northern Konkan. Eventually, the Satavahanas reasserted control over the Konkan, integrating Raigad’s ports into their expanding trade system.

The Mauryas of Konkan and the Question of Puri

However, at some point between the 4th and 7th centuries of the Common Era, a local dynasty styling themselves as Mauryas held sway over portions of the Konkan littoral, including areas of the present-day Raigad district. These rulers, distinct from the Mauryas of Maghada of earlier fame, appear to have exercised authority from a coastal capital referred to in scattered references as Puri. The precise location of this city has remained the subject of scholarly conjecture. However, notably, of the several sites proposed, Gharapuri, now better known as Elephanta Island, has been most frequently associated with this Mauryan capital.

The identification rests upon a convergence of early European travelogues, local place-names, and a small body of archaeological evidence. From as early as 1322 CE, travellers record the name Porus or Pori in connection with this coastal tract, possibly alluding to either a ruler or a settlement. The existence of villages on the island named Morbandar (“Maurya port”) and Rajbandar (“royal port”) has been taken by some as linguistic vestiges of a former political seat.

Chalukya Campaigns and the Western Ocean

By the mid-6th century CE, the Western Chalukyas of Badami had emerged as a dominant force across the Deccan. Their military campaigns reached into the Konkan as part of a larger effort to secure control over both inland and maritime corridors. King Kirtivarman I (r. 550–567 CE) led early incursions against the remnants of the Maurya and Nala powers.

It was under his grandson, Pulakesin II (r. 610–642 CE), that Chalukya control over the Konkan became more assured. The Aihole inscription of 634 CE, composed during Pulakesin’s reign, describes a remarkable naval expedition against a coastal settlement referred to as Puri, the goddess of the fortunes of the Western Ocean. The text boasts that the city was besieged by “hundreds of ships,” a phrase that has drawn attention from historians for its implications of both naval strength and perhaps a symbolic conquest.

Some scholars, including archaeologist Manish Rai (2014), suggest that this Puri may refer to Gharapuri (Elephanta Island). In his analysis, he argues that the island’s strategic maritime location, coupled with inscriptional and archaeological evidence, supports its identification as a fortified port and capital in the early medieval period.

The Kalachuris and the Shaiva Excavation at Gharapuri

In the centuries following Pulakesin’s campaign, the island of Gharapuri entered a new phase of prominence—not through warfare, but through temple-building. Between the 5th and 8th centuries CE, the great rock-cut shrines of Elephanta were excavated under the patronage of the Kalachuris, a dynasty based in Mahishmati (modern Maheshwar) in central India. The discovery of copper coins bearing Kalachuri symbols further supports their association with the site.

King Krishnaraja, a mid-6th century Kalachuri ruler and a devout follower of Shaivism, is often credited with commissioning the excavation of the main cave, which features the monumental Maheshmurti panel—one of the most iconic representations of Bhagwan Shiv in Indian art. The Kalachuris were closely aligned with the Pashupata cult, one of the earliest Shaivite sects that venerated Bhagwan Shiv as the supreme Devta. The Elephanta caves were likely part of a broader religious-political project by the Kalachuris to consolidate religious authority in coastal western India.

However, there are alternate theories to this as well. Interestingly, some local legends suggest that Pulakesin II commissioned the caves and that it took nearly a century to complete the labor. While these accounts are not supported by archaeological evidence, they reflect the enduring awe inspired by the monument.

While little is known about this period or who ruled the wider region with certainty, other than Gharapuri, Chaul also appears to have remained prominent during this time. The Chinese monk Xuanzang, writing in the 7th century CE, refers to a coastal location named Chimolo, which some scholars associate with Chaul or its immediate vicinity, suggesting that the site remained active in the early medieval era under these dynasties.

Shilahara Rule and Commercial Governance at Chaul

By the close of the 8th century CE, the northern Konkan, including the greater part of the present Raigad district, had come under the rule of the Shilahara dynasty. Originally feudatories of the Rashtrakutas, the Shilaharas soon established themselves as effective administrators and temple patrons in their own right. From the 9th to the early 13th century, they presided over a network of coastal settlements that included Chaul, Thane, and the surrounding ports.

Of these, Chaul retained its primacy as a trading centre. An Arab historian, Al-Masudi, writing in 916 CE, records that the fifth Shilahara king, Jhanjha, held court at Saimur (identified with Chaul), affirming the town’s continued relevance as both a port and political seat. Inscriptions from the later period reinforce this view. A record dated to 1096 CE, during the reign of Anantpal (or Anantadeva), the fourteenth Shilahara ruler, grants toll exemptions for the carts of two ministers operating through the port of Chaul (Chemuli). Such administrative privileges point to a well-organised system of trade regulation and revenue collection.

The long-standing rule of the Shilaharas came to an end in the early 13th century, when the Yadavas of Devagiri extended their influence westward from the Deccan plateau. Though less invested in maritime governance than their predecessors, the Yadavas maintained control over Raigad’s coastal trade and continued its integration into wider inland networks.

During this period, towns such as Goregaon and Pen grew in importance as minor ports and resting stations. Pen, in particular, appears to have served as a redistribution centre for rice, salt, and other commodities, supported by its strategic location near the Bor Pass. The revised district Gazetteer notably mentions that “a number of carved stones about the town appear to belong to an unusually large temple of about the thirteenth or fourteenth century.”

Alibag and the Bene Israel Settlements on the Raigad Coast

While trade remained a politically significant aspect of Raigad’s early history, the region of Alibag, now the district’s administrative centre, holds a quieter but enduring significance in Raigad’s social history. Located along the central coast, Alibag was historically linked to the Bene Israel, a Marathi-speaking Jewish community who are believed to have settled along the Konkan after being shipwrecked over two millennia ago.

According to local tradition, the settlement’s name derives from Eli, a prosperous Jewish resident whose coconut and mango plantations became known as Eli-cha-bagh—later shortened to Alibag. Though the precise date of the community’s arrival is uncertain, the Bene Israel established themselves in surrounding villages such as Navgaon, Revdanda, Nagaon, and Korlai, adopting local customs while maintaining distinct religious practices.

By the 19th century, Alibag had emerged as a modest port engaged in the export of rice, charcoal, and dried fish to Bombay and neighbouring districts. The construction of the Magen Aboth Synagogue in 1843, located in what is known as the “Israel area” of the town, marked the formal institutional presence of the Bene Israel in the region. Though their numbers have declined in recent times, their cultural legacy remains embedded in the urban and coastal fabric of Raigad.

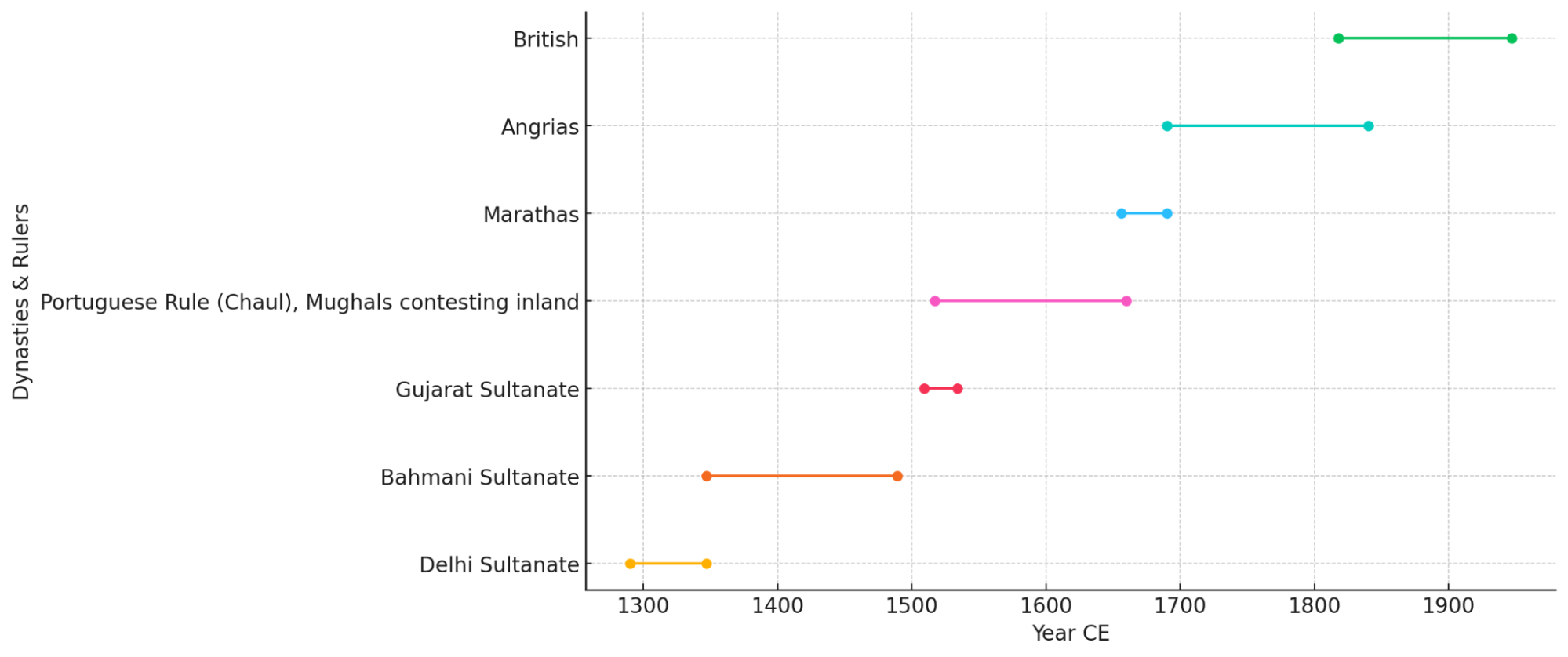

Medieval Period

After the fall of the Yadavas in the early fourteenth century, the territory that is now Raigad district did not come immediately under the control of distant sultanates. Instead, local chiefs and dynasties continued to wield authority, especially in the forested and coastal tracts. According to the district Gazetteer, the southern stretches of Raigad and the broader Konkan coast remained under the influence of the Vijayanagara or Anegundi kings (present-day Karnataka) until at least 1377. The Kanara kings, identified as a Lingayat dynasty, maintained their headquarters at Anegundi, providing a base of regional authority that extended to southern Raigad’s interior.

The Koli community played an especially prominent role in this era. Villages along the creeks, islands, and estuaries of Raigad district were often ruled by Koli chiefs.

The Bahmani Sultanate and the Contest for Chaul

By the early 15th century, the attention of the Bahmani Sultanate, then the dominant force in the Deccan, turned toward the economic and strategic assets of the Konkan coast. Chaul (present-day Revdanda–Chaul, Raigad district), with its deep natural harbour and vibrant marketplace, became the primary focus of Bahmani ambitions in the region. In 1429, a Bahmani expedition is said to have moved by sea to compel local chiefs, including those of Redi (now in Sindhudurg) and Raigad, to acknowledge Bahmani authority and pay tribute.

The process was uneven and often contested. In 1469, Muhammad Gawan, the celebrated minister of Sultan Muhammad Shah Bahmani II, led a formidable force that drew on contingents from Junnar (now Pune district), Chakan, Kolhapur, Dabhol (Ratnagiri), and local strongholds in Raigad. These campaigns were part of a wider strategy to consolidate sultanate control over the fragmented political landscape of the Konkan, integrating Raigad’s ports and trade routes into the administrative and military network of the Deccan. The establishment of Junnar as a significant centre in 1451 reinforced these connections and helped anchor the coastal regions more firmly to the inland sultanates.

Chaul developed into a significant port during this period. Ferishta, writing in 1380, identified Chaul as the principal port of the Bahmani Sultanate. By the end of the fourteenth century (1398), it was known as one of the main coastal hubs in the Konkan region, from where the Bahmani king Firuz Shah (reigned 1397–1422) sent ships in search of goods and skilled workers from distant lands. Russian traveler Athanasius Nikitin visited in the 1470s, describing Chaul—called “Chivil”—as populous, with a majority of residents of modest means, and noted the curiosity shown toward foreign visitors. In about 1490, Chaul passed from the Bahmani to the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, serving as its main port for over a century.

Documentation and traveler accounts continued into the Portuguese era. By the early sixteenth century, the Portuguese established a trading factory in Chaul after 1521, and the port remained prominent in both local and international records. The town was renowned for cotton textiles, as described by Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema and Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa. Cotton production supported livelihoods and attracted foreign traders.

Portuguese Expansion and Rivalries on the Raigad Coast

With the decline of the Bahmani Sultanate toward the end of the fifteenth century, the port of Chaul, long a prized asset of that dominion, passed into the hands of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. Situated at the mouth of the Kundalika River, and commanding both maritime and inland routes, Chaul continued to flourish under Ahmadnagar's protection, serving for several decades as its principal port on the western seaboard.

By the early sixteenth century, however, the growing presence of the Portuguese along the Konkan coast introduced a new and disruptive element into the region's political economy. Drawn by the prospects of trade and strategic control, the Portuguese sought to establish a permanent foothold in Chaul. In 1521, it is recorded that Burhan Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar, in a calculated effort to secure commercial advantage, granted them permission to erect a fortified trading post at Revdanda, adjacent to Chaul, in exchange for trade privileges and assurances of political neutrality.

The fort of Revdanda was completed by 1524 and marked a significant moment in the consolidation of Portuguese power on the Konkan coast. However, their growing influence quickly provoked resistance. In 1528, a naval force of some eighty vessels dispatched by the Gujarat Sultanate launched an assault upon Portuguese-held Chaul, damaging trade installations and undermining Ahmadnagar’s maritime interests in the process. The Portuguese response was swift and severe: they seized several Gujarati ships and burned no fewer than six towns along the Nagothna (Amba) River in a show of naval strength.

Ahmadnagar Sultanate reasserted its position in 1529, taking direct control of Chaul from the Portuguese. Yet the town would continue to see contestation in the decades that followed. In 1540, Burhan Nizam Shah seized the important inland fort of Sankshi, near Pen, from the Gujarat Sultanate. The defeated Gujarati commandant sought Portuguese support to regain the position. Although the Portuguese succeeded in retaking the fort, they deemed it too costly to maintain and ultimately ceded it to Ahmadnagar, a gesture that revealed the limits of their inland ambitions at that time.

The escalating Portuguese presence along the coast stirred apprehension across the Deccan and beyond. By 1570, a rare alliance had formed between four major powers (Ahmadnagar, Bijapur, Calicut, and the distant Sumatran kingdom of Achin) united by their shared interest in halting Portuguese expansion. Murtaza Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar led an expedition against Chaul, but his forces failed to dislodge the Portuguese garrison. In retaliation, the Portuguese raided the inland town of Kalyan (in Thane district), setting fire to its suburbs and reasserting their coastal dominance.

Nevertheless, Portuguese control remained contested. In 1594, Ahmadnagar forces mounted yet another assault on Chaul and dispatched cavalry columns to ravage Bassein (modern Vasai, Palghar district), underscoring the continued resistance to Portuguese encroachment. These events, frequent and often brutal, signalled not only the fierce competition for Chaul and its environs but also the shifting balance of power between Indian sultanates and European maritime powers on the western coast.

Korlai Fort and the Luso-Indian Speaking Village

As Portuguese ambitions on the Konkan intensified in the early 1500s, Raigad’s coastline witnessed a surge in new fortifications and international rivalries. After securing permission from Burhan Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar, the Portuguese built Revdanda Fort in 1524 and soon set their sights on the rocky promontory of Korlai (present-day Korlai, Raigad district). In 1521, construction began on Korlai Fort, intended as a companion to Revdanda and a sentinel guarding the bay.

Initially, Ahmadnagar sultans allowed limited Portuguese presence, but as Portuguese influence grew, tensions escalated. By the mid-16th century, as noted above, the region was a battleground. The Portuguese, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, and the Gujarat Sultanate repeatedly clashed over fortifications, control of river mouths, and rights to levy trade. In 1594, after a period of uneasy coexistence, the Portuguese captured Korlai Fort in a major assault. While the victors partially demolished the stronghold (leaving only its central tower and artillery), the fort’s dominance over the bay signaled a new era of European control along Raigad’s coast.

Their hold over this village was so strong that Korlai developed a distinctive Portuguese-influenced creole language, termed Luso-Indian (see Language for more), which survives to this day, and the fort itself became a contested landmark in the struggles that would follow.

Siddis of Janjira and Murud

While the Portuguese focused on the northern creeks, the southern coastline of Raigad saw a different contest unfold. During the late 1400s, the island now known as Janjira (off Murud, Raigad district) was fortified by Ramrao Patil, a Koli admiral of the Ahmadnagar navy. Seeking to defend local fishermen from piracy, Patil’s wooden stronghold soon became a strategic prize.

Political intrigue led to dramatic change. In 1498, Piram Khan, acting on orders from the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and allied with a force of Siddis (military specialists of Abyssinian origin), seized Janjira through subterfuge. After gaining entry to the fort under the guise of merchants, they captured the island and ousted Ramrao Patil. Malik Ambar, the celebrated regent of Ahmadnagar, later ordered the replacement of the wooden defenses with massive stone ramparts, granting the island to the Siddis in recognition of their loyalty and naval prowess.

Throughout the 1600s and 1700s, Janjira developed into the principal seat of Siddi authority on the Konkan. The Siddis, who had now hereditary admirals and governors, maintained a precarious independence, nominally allied to the Deccan sultanates or the Mughal Empire, but acting autonomously in matters of trade and war. The fortress of Janjira, with its formidable sea walls and batteries, withstood repeated sieges by the Portuguese, the Marathas, and even the British.

Even Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj launched several campaigns to capture Janjira but was repulsed each time. In response, the Marathas built new forts such as Birwadi (near Mahad, Raigad district) and Lingana (near Raigad Fort) to contain the Siddi threat. It is important to note that the ongoing rivalry between these powers, notably, shaped the political geography of Raigad’s coast, creating a unique zone where European, Deccan, and local powers all vied for dominance.

Marathas

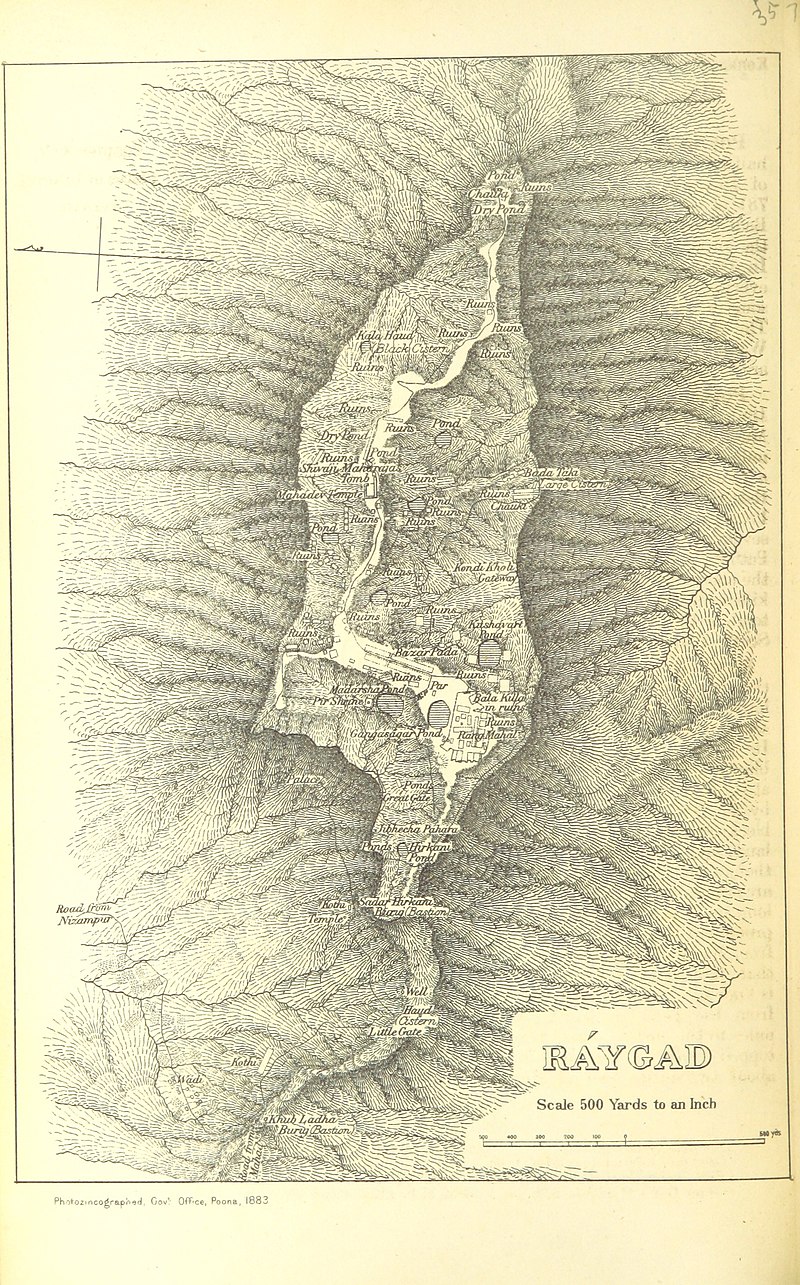

It was here that Shivaji established his capital at Raigad Fort, a site of immense and strategic importance, from which the district later derived its name. However, long before it became the Maratha capital, the site of Raigad, then called Rairi, was held by local chieftains and changed hands over successive regional powers. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1883), it was constructed and controlled by Chandraraoji More, a local chief who possibly belonged to a Maratha community. Positioned within the Western Ghats, the fort served as a strategic outpost before being captured by Shivaji Maharaj in 1656. He renamed it Raigad, meaning “royal fort,” and began developing it into a central administrative base.

Shivaji’s Naval Ambition on the Konkan Coast and Kolaba Fort

By the early 1660s, Shivaji Maharaj had secured key victories in the Deccan, weakening major adversaries such as the Bijapur Sultanate. With his inland control firmly established, he turned his focus toward the Konkan coast, recognizing its immense strategic importance, not only for defending the Maratha homeland, but also for expanding maritime trade, securing supply lines, and projecting naval power.

Among the forts selected for coastal fortification was Kolaba Fort, situated just off the shore of present-day Alibag in Raigad district. According to the Kolaba District Gazetteer (1882), the first known reference to Kolaba occurs in the mid-seventeenth century, when Shivaji identified it as one of the key coastal posts vital to the defense of the Konkan, which had recently come under his control south of Kalyan (Thane district).

In 1662, he undertook reconstruction and strengthening works at Kolaba, transforming it into a naval station equipped to monitor and challenge foreign maritime powers—chiefly the Portuguese and the Siddis.

Work on Kolaba continued beyond Shivaji’s lifetime and was completed in 1681 under Sambhaji Maharaj, highlighting the enduring commitment of the Maratha state to establishing coastal fortresses as part of a broader maritime strategy. In later decades, the fort would serve as the capital of the Kolaba State under Kanhoji Angre, the formidable admiral of the Maratha navy, who elevated it into a bastion of resistance against European encroachment. But even before its rise under the Angres, Kolaba stood as a testament to Shivaji’s early vision of sea power as essential to securing Hindavi Swarajya.

Raigad as the Capital of the Maratha Empire

While Shivaji was asserting Maratha control over the Konkan coast, he was also consolidating inland authority through bold political and military action. In January 1664, Shivaji launched one of his most famous and strategic military operations: the raid on Surat. At that time, Surat was one of the wealthiest trading ports in the Mughal Empire, serving as a crucial commercial hub where merchants from Europe, Persia, and the Middle East conducted business. The city was home to vast Mughal treasures, warehouses filled with riches, and important foreign trading posts, including the British and Dutch East India Companies.

Following his dramatic escape from Mughal captivity in Agra in 1666, Shivaji returned to Raigad and began reorganizing the Maratha administration. Anticipating further conflict with Aurangzeb, he focused on strengthening the military, expanding the fort network, and enhancing intelligence systems. These efforts culminated in Raigad being selected as the Maratha capital.

Shivaji’s Rajyabhishek at Raigad, 1674

In June 1674, Shivaji Maharaj was formally crowned as Chhatrapati at Raigad Fort. The coronation, known as Rajyabhishek, was officiated by the scholar Gaga Bhatt of Kashi and attended by nobles, diplomats, and envoys from across India. The ceremony marked the assertion of a sovereign Maratha rule (Hindavi Swarajya) outside the influence of both the Mughal Empire and Deccan Sultanates.

The Siege of Raigad and Mughal Capture (1689)

After Shivaji’s death on 3 April 1680, his son Sambhaji Maharaj succeeded him. However, Sambhaji’s reign faced both internal dissent and intensified Mughal pressure. In 1688, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb ordered a renewed assault on Raigad, entrusting the mission to general Zulfiqar Khan. The siege that followed cut off supplies and surrounded the fort from all directions.

With Sambhaji’s capture and execution in 1689, leadership passed to his half-brother Rajaram Maharaj, who was covertly evacuated from Raigad before its fall. The fort was eventually captured by the Mughal forces later that year. It is noted in the district colonial Gazetteer (1883), that in 1689, Mughal general Zulfiqar Khan captured Raigad, renaming it Islamgarh. However, the Marathas reclaimed the fort, years later, in 1735.

Angres of Kolaba, Kanhoji Angre and the Rise of a Maritime State

The siege and fall of Raigad in 1689 marked a major turning point in Maratha history. As Mughal forces captured the fort and briefly renamed it Islamgarh, Raigad’s political prominence waned, and much of the Maratha stronghold in the region fell into disarray. However, even as the inland capital receded in influence, a new centre of power began to take shape along the Konkan coast.

In the closing years of the 17th century and into the early 18th, a formidable maritime leader named Kanhoji Angre (also written Angria) emerged. Hailing from Angarwadi near Harnai in Ratnagiri district, Kanhoji rose through the ranks to become the chief architect of Maratha naval power. His early seafaring exploits and sharp political instincts established him not only as the guardian of the western coastline, but also as a semi-independent ruler in his own right.

By the turn of the 18th century, the Maratha Empire under Chhatrapati Shahu was in the process of reasserting itself after years of turmoil following Sambhaji Maharaj’s execution. During this time, Kanhoji Angre emerged as a key figure in securing the Maratha coastline from both foreign intrusion and rival factions.

According to the Bombay Presidency Gazetteer (1886), Kanhoji’s authority began to solidify in 1713, when he formally swore allegiance to Chhatrapati Shahu. In recognition of his strategic and military value, Kanhoji was granted control over a number of key coastal forts, including Kolaba, Khanderi, Vijaydurg, Avshṭagad, Rajapur, and Kharepatan. This effectively made him the undisputed master of the Konkan coast.

His rise was strongly supported by Balaji Vishwanath, the first Peshwa and the chief architect of Shahu’s administrative revival. Balaji played a crucial role in securing Kanhoji’s loyalty, recognising the need for a powerful naval commander to stabilise the volatile coastline. The two leaders coordinated efforts to push back against the Siddis of Janjira, long-standing naval adversaries entrenched along the coast. Together, they succeeded in recapturing several territories that had remained under Siddi control for decades, thereby asserting Maratha dominance at sea.

Formalization of the Kolaba State

Despite Kanhoji’s allegiance to Shahu, his increasing independence and control raised concern within Maratha political circles. The Peshwa at the time, Bahiroji Pingale (Balaji’s predecessor), was dispatched to check Kanhoji’s growing influence. In a dramatic turn of events, Kanhoji defeated the Peshwa’s forces and captured Pingale himself, displaying both tactical brilliance and political boldness.

Rather than triggering a prolonged internal conflict, the incident led to negotiations with Chhatrapati Shahu. As part of the settlement, Kanhoji released Bahiroji Pingale and was granted official control over 26 forts, thus formalizing the Kolaba State with its administrative base at Kolaba Fort.

Though nominally under Maratha sovereignty, the Kolaba State operated with substantial autonomy. Kanhoji levied taxes, conducted naval operations, and maintained a private navy independent of Peshwa command. This marked a rare moment in Indian history when a regional naval commander transformed into a semi-independent ruler, commanding not just the seas but the coastal heartland of Raigad district and beyond.

Military Strength and Naval Strategy

Kanhoji Angre’s rise was not solely due to his political acumen or local alliances—it was his ability to build and command a powerful navy that distinguished him. He developed a highly mobile and well-organized maritime force suited to the challenges of the Arabian Sea. This navy enabled him to exert control over the western coast and challenge the European powers who had long dominated Indian waters.

According to the Kolaba Gazetteer (1883), Kanhoji’s fleet consisted primarily of two types of vessels: grabs and gallivats.

- Grabs were larger warships, often carrying 9 to 12 cannons, with a crew complement of 150–200 men.

- Gallivats were smaller, faster vessels, ideal for quick assaults and evasive manoeuvres.

His navy was manned by a diverse group of seafarers (including Maratha sailors, Arabs, Portuguese defectors, African mercenaries, and other skilled mariners). This diversity reflected the cosmopolitan nature of maritime warfare in the region and gave his forces a distinct tactical edge.

Kanhoji employed hit-and-run tactics, ambushing enemy ships, looting cargo, and retreating to fortified coastal strongholds before European reinforcements could respond. These operations were often brutal: after disabling enemy vessels with cannon fire, Angre’s men would board with swords drawn, fighting hand-to-hand in the chaos of broken masts and blazing decks. His mastery of the sea turned the Konkan into a zone of Maratha maritime control.

Clashes with European Powers

The growing reach of Kanhoji Angre inevitably brought him into conflict with the European trading powers—especially the British East India Company and the Portuguese Estado da Índia, both of whom maintained trading posts and naval bases along the coast.

By the early 1720s, Kanhoji Angre's naval campaign against British interests in western India had escalated significantly. His fleet launched repeated attacks on British merchant ships near Mumbai, asserting Maratha sovereignty over the coastal waters and demanding chauth: a form of protection tribute for safe passage through territories effectively under his control.

The British East India Company, increasingly frustrated by these demands, branded Kanhoji a pirate. Yet this label said more about imperial irritation than legal reality. Kanhoji operated as a recognised officer within the Maratha Empire, with full authority to collect tribute and regulate maritime trade in his domain.

Battle of Khandheri, 1718

Tensions had been rising since 1717, when Kanhoji attacked a British merchant vessel near Surat. The British East India Company responded with military force. One of the earliest major encounters was the Battle of Khanderi in 1718, when the British mounted a full-scale assault on Khanderi Island, a critical naval base under Kanhoji’s command.

Despite their superior weaponry and naval infrastructure, the British suffered a humiliating defeat. According to the Kolaba Gazetteer (1883), their forces were heavily outnumbered, and only 40 British soldiers ultimately participated in the campaign, as local Indian recruits were reluctant to engage Kanhoji’s forces. The fort on the island held firm, and the British failed to secure any lasting advantage. The failure cemented Kanhoji’s image as a naval tactician capable of defeating European powers on his own terms.

In 1722, the British and Portuguese joined forces in a combined offensive against Vijaydurg (Sindhudurg district), one of Kanhoji’s key strongholds. Once again, their efforts were repulsed by clever positioning and superior maneuvering on Kanhoji’s part. The British, realising their naval superiority was not guaranteed, even attempted to bribe Kanhoji to align with them. He refused, preserving his autonomy and reputation.

These engagements marked a rare phase in Indian history when an Indian naval commander repeatedly defeated European fleets, safeguarding native sovereignty in waters long dominated by imperial trade powers.

Cultural and Religious Patronage

Kanhoji Angre’s legacy was not confined to his military conquests. He also left a strong imprint on the cultural and religious landscape of Alibag, the town that became his home and administrative centre in his later years.

At the peak of his power in 1720, Kanhoji commissioned the construction of the Hirakot Fort (also referred to as Hirakot Old Fort), near the banks of the Hirakot Lake in Alibag. Though originally intended as a military bastion, the structure was later repurposed by the British as a prison, and continues to serve that function today. Within its walls, Kanhoji is believed to have resided during his final years.

As part of his religious devotion, Kanhoji also established a Mandir dedicated to Kalamba Devi, his kul devi. This Mandir, known as the Kalambika Mandir, was initially situated within the Hirakot Fort itself. When the fort was later converted into a jail under British rule, the Mandir was relocated to Tilak Road in Alibag, where it remains a site of local worship.

Economic Sovereignty

One of the clearest markers of Kanhoji Angre’s autonomy was his ability to control and manage economic systems independent of the central Maratha authority. Beyond collecting chauth (tribute) from ships sailing through his waters, Kanhoji also operated his own mint, issuing currency under his own administration—a privilege typically reserved for sovereign rulers.

According to the Kolaba Gazetteer (1883), three types of currency circulated in the region during the Angria period:

- The Alibag-Kolaba rupee (also known as the “old rupee”), which bore Persian inscriptions,

- The Janjira-Kolaba rupee (or “new rupee”), with the Marathi word "Shri" and a drilled hole,

- Alibag copper pice, used in local trade.

Some coins bore the stamp of the Satara Chhatrapati, reflecting nominal allegiance to the Maratha throne, while others were issued directly under the Angria name, demonstrating de facto independence. This parallel economy enabled the Kolaba State to manage its own fiscal policies and enforce taxation within its waters and ports.

The regional economy, too, thrived. Tax records from 1878, while postdating Kanhoji’s era, offer a glimpse into the continuing prosperity of the district. Populations were diverse: Brahmins, Prabhus, Marathas, Gujarati Vaniis, Muslims, with annual incomes for most ranging between £10 and £50, while wealthier individuals earned upwards of £1000. Money-lending and credit were primarily managed by Marwaris, Gujaratis, and Marathi Vaniis. By 1854, local banking houses in Alibag issued exchange bills (hundis) for trade with major cities such as Mumbai, Puna, and Banaras (Uttar Pradesh), indicating a well-integrated financial system.

Kanhoji’s control over trade, ports, and currency, in many ways, made Kolaba one of the most economically self-reliant regions along the Konkan coast.

Kanhoji’s Death and Samadhi (1731)

After a long and storied career at sea, Kanhoji Angre spent his final years in Alibag. He passed away in 1731, leaving behind a formidable maritime legacy unmatched in 18th-century India.

In recognition of his achievements, a samadhi (memorial tomb) was constructed at Shivaji Chowk in Alibag, where it still stands today. This site remains a place of public veneration, visited by locals who offer flowers in his memory and regard him as a measure of Maratha resilience and maritime strength.

Fracture and Rivalry Among the Angrias

With Kanhoji’s passing, the once-unified Angria command began to unravel. His sons, Tulaji, Sekhoji, and Manaji, vied for power, each seeking to dominate the territories their father had so skillfully consolidated. This internal rivalry led to instability, weakening the central authority of the Kolaba State just as foreign threats persisted.

Instead of strengthening the navy Kanhoji had built, the Angria brothers often used it against each other, draining resources and eroding the disciplined coordination that had once made their fleet invincible. As they fought among themselves, European powers (particularly the British) and even the Peshwa in Pune began to eye the weakening Kolaba State with interest.

The most decisive blow came in 1756, when a joint British-Peshwa force attacked and captured Vijaydurg (which lies in Sindhudurg district), one of the Angrias’ most important naval bases. This campaign marked the collapse of independent Maratha naval power in the Konkan and ended the era of Angria dominance at sea. The once-feared Angria fleet was broken, and its commanders were relegated to regional landlords under Peshwa oversight or British suspicion.

Raghuji Angre and Later Prosperity

In the wake of internal strife and the loss of key forts, the Angria house saw a revival under Raghuji Angre, who ascended to leadership of the Kolaba State in 1758 after the death of his father, Manaji Angre. Though much of the naval glory from Kanhoji’s time had faded, Raghuji managed to bring stability and prosperity back to the region, maintaining the Angria legacy of autonomy and strategic importance.

That same year, the Siddis of Janjira, long-time maritime rivals of the Marathas, launched a damaging assault on Kolaba, targeting temples and villages. Raghuji, with the assistance of the Peshwa, successfully repelled the attack. In a show of loyalty and martial capability, he then led a counter-offensive, capturing Underi Fort on 28 January 1759, which he presented to the Peshwa as a token of gratitude. He later seized Padmadurg Fort as well, further securing Kolaba’s maritime boundaries.

The capture of Janjira itself seemed within reach, but broader Maratha military demands, particularly the recall of Sadashivrao Bhau to northern India, prevented its completion. Despite accusations of privateering and harassment of British ships, Raghuji remained largely aligned with the Peshwa’s interests. Notably, private naval campaigns by the Angrias ceased after his reign, marking the end of Kolaba’s era of active maritime conflict.

Under Raghuji, Kolaba flourished. According to English sea captain James Forbes, who visited in 1770, the region was fertile, economically active, and governed with considerable sophistication. Forbes described the reception he received from Raghuji as hospitable and generous, further indicating the ruler’s engagement with diplomacy and trade.

British Annexation of Kolaba (1793–1840)

Following Raghuji Angre’s death in 1793, the Kolaba State entered a period of decline and political instability, worsened by disputes over succession. His infant son, Manaji Angre II, was placed on the throne under the protection of Jai Singh Angre, an illegitimate son of Raghuji. However, this arrangement lacked Peshwa approval and sparked considerable unrest.

Anandibai Bhosale, Raghuji’s widow, attempted to remove Jai Singh from power but failed, resulting in her banishment. She later returned with an army, besieged Kolaba Fort, and imprisoned Jai Singh. In the chaos that followed, Baburao Angre, another member of the family, seized the opportunity to establish control. After his death in 1813, his widow administered the state briefly until Manaji Angre II proclaimed himself ruler. In exchange for territorial concessions, the Peshwa recognised his position, but these lands were later restored to the Angrias shortly before the British and Peshwas went to war in 1818.

This period of turmoil greatly reduced the state’s revenues, which fell to about Rs. 3,00,000 annually, a significant drop from earlier decades. The weakening of the Angria authority allowed the British to increasingly intervene in Kolaba’s affairs.

In 1821, Kashibai, the widow of Baburao Angre, approached the British Government to secure her son Fatesingh’s claim to the throne. A treaty signed in 1822 formalised British recognition of Kolaba’s ruler while asserting colonial authority. The treaty preserved land rights and family pensions, but the autonomy of the Kolaba State was effectively lost.

Further succession disputes continued. In 1839, Yashodabai’s son was recognised as Kanhoji Angre II, with Vinayak Parshuram Biwalkar appointed as karbhari (administrator). However, Kanhoji II died the same year. With no clear heir, the British moved to annex Kolaba under the pretext of the Doctrine of Lapse in 1840, citing the absence of a legitimate successor and the inefficiency of small princely states.

Personal belongings of the Angrias were distributed among surviving family members, and Raghuji Angre II’s widows were granted annual pensions. Thus ended the independent political legacy of the Angrias, whose power had once defied empires.

Colonial Period

The roots of British authority in what is now Raigad (formerly Kolaba) district stretch back to the mid-eighteenth century. The first British possessions in the region, Dasgaon and Komala (in present-day Mahad taluka), along with the strategic fort of Bankot at the Savitri River’s mouth, were acquired in 1756. These acquisitions, made through diplomatic arrangements with the Peshwa, marked one of the earliest British footholds in the Konkan and laid the groundwork for later expansion.

Expansion After the Maratha Wars

The landscape of power in Raigad changed dramatically after the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1818), which ended Maratha sovereignty and ushered in a new era of British ascendancy. Following Kashibai Angria’s treaty with the British and the broader defeat of Maratha forces, the British moved to annex Underi and Revdanda (now in Alibag and northwest Roha) as well as clusters of villages in what are today the Panvel and Karjat subdivisions (now split between Raigad and Thane). Between 1818 and 1840, further annexations from local rajas consolidated British control across the district.

In 1840, Kolaba was formally incorporated under direct British rule, initially overseen by a Political Superintendent. Four years later, administrative reforms saw the appointment of an Agent, and Kolaba became subject to the standard legal framework of the Bombay Presidency, likely administered from Thane at first.

District Formation and Growth

This growing administrative apparatus continued to evolve. In 1869, Kolaba was granted the status of an independent collectorate, distinct from Thane. Over the next two decades, boundary changes brought Panvel (1883) and Karjat (1891) into Kolaba’s fold. By 1882, the district included five subdivisions: Alibag, Pen (with Nagothna), Roha, Mangaon, and Mahad, encompassing more than a thousand villages. Governance was a patchwork: about half the villages were khalsa (directly administered), others were managed by hereditary revenue farmers (khots), and a smaller portion were alienated as inam grants. This evolving structure reflected the administrative complexity and the district’s shifting political landscape under British rule.

The First War of Independence, 1857

As British control took firmer hold, so too did currents of dissent and unrest. The district’s engagement with the broader national movement surfaced most vividly during the 1857 Uprising. While the main centers of revolt were in North India, Raigad’s connection to this moment comes through individuals such as Vishnubhat Godse, a Marathi priest and writer from Varsai (near Pen), whose celebrated travelogue, Majha Pravas, records a firsthand account of the rebellion and its impact, linking local experience to the wider tide of resistance.

Acharya Vinoba Bhave and Bhoodan Movement

Acharya Vinoba Bhave, the spiritual successor of Mahatma Gandhi, was born Vinayak Narahari Bhave, in 1895, in Raigad district. He was a 20th-century saint, scholar and social reformer. He eventually moved to Wardha district, where he made a monumental contribution to post-independence India through his non-violent Bhoodan Movement.

Education and Print Culture

Amid these social crosscurrents, the late nineteenth century brought significant advances in education and public discourse. The British government and local communities established regional language schools, with the first in Mahad (1840), followed by more in towns such as Alibag, Nagothna, Madgaon, Pen, and Roha. By the early 1880s, the district’s network of schools had expanded remarkably, including the first girls’ school in Alibag (1861), contributing to rising literacy.

Alongside formal education, Raigad (especially Alibag) emerged as a center of Marathi print culture, with newspapers and magazines like Satya Sadan, Sharabh, Satdharma Dip, and Abala Mitra circulating widely. These publications reflected a growing intellectual engagement, addressing themes from religious reform to women’s issues and social progress. The district’s vibrant reading culture not only encouraged debate but also helped nurture a sense of civic identity.

Land Tenures and Agrarian Structure

As education, civic institutions, and political life developed in 19th-century Kolaba (modern-day Raigad), rural society continued to be shaped by an intricate and layered system of land tenure. Villages across the district were previously classified into a mix of government-owned lands, private estates, and areas managed by hereditary revenue collectors, known locally as khots. These systems coexisted with varied tenant arrangements, reflecting both traditional practices and colonial-era reforms.

In most cases, landowners (many of whom were absentee landlords) collected rent from cultivators, with rates that differed based on land ownership type. Private villages typically charged higher rents than government-controlled ones, and tenants paid either in cash or kind, depending on agreements and the quality of the land they farmed.

It is documented in the Kolaba District Gazetteer (1883), that there were 1,064 villages in the district at the time, out of which:

- 985 were government-owned, and

- 79 were alienated (inam villages).

Among the government villages:

- 500 were managed directly by landholders,

- While 435 were administered through khots (village-level revenue contractors).

The inam villages were held by a mix of communities: Brahmans, Prabhus, Marathas, Muslims, and even individuals from lower castes, many of whom did not reside in the villages they controlled and instead collected rent through intermediaries.

Rent collection practices varied by location, tenure, and land productivity. The Gazetteer notes that rents in private villages were typically 25% higher than those in government-managed ones. In surveyed villages, rents were assessed based on the quality and productivity of the land, while in unsurveyed areas, landlords often relied on annual inspections and collected a fixed portion of the crops. Examples from the 1882 records in Alibag illustrate this variation:

- On rice lands, rents ranged from 240 to 1,260 pounds per acre.

- In upland areas, where crops like nagli and vari were cultivated, rent could reach 160 pounds per acre—collected only once every four to five years, when the land was fit for tillage.

- In some cases, estates were divided among multiple owners, while in others, they remained jointly managed, without division of shares.

The Khot System

The khot system stood as a powerful and persistent institution under both Maratha and British rule. A khot acted as a village-level revenue contractor, responsible for collecting land taxes on behalf of the state, but often operating with substantial autonomy and influence over local affairs.

According to the Kolaba Gazetteer (1883), of 485 khoti villages:

- 478 were held by private landlords

- 7 were classified as waifat khots (service khots)

These waifat khots were hereditary officers like deshmukhs and deshpandes, granted rent-free rights to villages by earlier regimes. While their privileges were retained under Maratha rule as long as revenue was paid, they often exercised landlord-like authority. Their presence was especially notable in the Pen and Roha subdivisions.

Though the khot system provided continuity in administration, it also became a source of conflict. Khots were frequently accused of tenant exploitation, and colonial land reforms struggled to balance traditional power structures with the rights of cultivators. As colonial rule deepened, these tensions would shape wider debates around justice, land, and social hierarchy in the region.

Chavdar Tale and the Mahad Satyagraha (1927)

While tensions over land and revenue marked one form of inequality in Raigad, another, perhaps even more deeply rooted form of oppression stemmed from the rigid social hierarchies of the caste system. In the early 20th century, as India’s freedom movement gathered momentum, Raigad district became the site of a landmark struggle, not for political independence, but for basic human dignity.

This struggle came to a head in the town of Mahad in 1927, with a civil rights protest that would go on to reshape the anti-caste movement in India. Known as the Mahad Satyagraha, it was led by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, a rising leader and visionary who sought to challenge centuries-old caste-based restrictions and reclaim public space for the marginalized.

At the heart of this protest was Chavdar Tale, a public water tank in Mahad. Though legally open to all castes following a 1923 resolution by the Bombay Legislative Council, Dalits, considered "untouchables" within the caste hierarchy, were still denied access in practice. Public spaces, especially sources of water, remained powerful measures of social exclusion.

Recognizing this injustice, Ambedkar chose Mahad as the site for a bold assertion of equality. He received strong support from progressive figures, including Surendranath Tipnis, then president of the Mahad Municipality, who officially declared that public spaces in the town were accessible to everyone, regardless of caste.

Following a public meeting, Ambedkar led thousands of participants to Chavdar Tale, where he and many others from the Dalit community drank from the water tank as an assertion of equal rights. Notably, commenting on this moment, in 1927, Ambedkar said, “We are not going to the Chavadar Tank to merely drink its water. We are going to the Tank to assert that we too are human beings like others.”

Very significantly, the Mahad Satyagraha is widely recognized as a landmark moment in the struggle against caste discrimination. It is often referred to by many as the Dalit community’s “Declaration of Independence” and March 20 is now observed as Social Empowerment Day across India to commemorate this event.

Today, Chavdar Tale remains a site of historical importance. The lake and the nearby Ambedkar Smarak continue to attract visitors, serving as reminders of the ongoing struggle for social equality and dignity which has taken place in Indian history.

V.B Shiledar and Chirner Jungle Satyagraha

Around the same time, resistance was also taking shape in rural and forested parts of Raigad - this time in response to colonial forest policies that restricted access to traditional lands and resources. In Panvel taluka, V. B. Shiledar emerged as a key figure in organizing resistance among farming communities.

A radical thinker and skilled organizer, Shiledar was deeply committed to the cause of the rural poor. He emerged as a prominent figure within the Panvel Congress and was instrumental in revitalizing the Satyagraha Mandal—a local committee formed to plan and lead nonviolent resistance movements based on Gandhian principles of satyagraha. These mandals served as platforms through which national campaigns like civil disobedience and anti-tax protests could be carried out at the local level, connecting village grievances with the wider struggle for independence.

One of the significant events associated with Shiledar’s activism was the Chirner Jungle Satyagraha of 1930, which took place in the village of Chirner, now part of Uran taluka in Raigad district. At the time, British colonial authorities had imposed strict forest regulations that curtailed the rights of local communities to access resources such as firewood, grazing land, and timber: resources that were essential to their survival.

In response, Shiledar and other local leaders organized a peaceful protest, part of a larger wave of nonviolent civil disobedience inspired by Gandhian principles. On September 25, 1930, a group of villagers marched into the forest in open defiance of the colonial laws, asserting their traditional rights.

However, what began as a peaceful satyagraha ended in tragedy when British police forces opened fire on the unarmed demonstrators. Nine villagers were killed, including Joshi Mamledar, a local administrative officer who had sided with the protestors. The brutality of the crackdown shocked the region and galvanized support for the anti-colonial cause.

In the aftermath of the violence, the local community came together to honor the fallen. A Smruti Stambh (memorial pillar) was erected on January 3, 1932, as a tribute to the courage and sacrifice of the Chirner satyagrahis. However, in an attempt to suppress public memory, the British administration demolished the memorial later that same year.

Refusing to let the story fade, local leaders rebuilt the Smruti Stambh in 1939, under the leadership of N.B.G. Khare, a prominent member of the Mumbai government at the time. Decades later, in 2005, parts of the original, destroyed pillar were recovered and have since been preserved at the site as tangible reminders of the community’s resilience.

Today, the site is known as the Chirner Hutatma Smarak. Every year, on September 25, residents and visitors gather to pay tribute to the martyrs through ceremonies, public gatherings, and formal tributes.

Post-Independence

Following India’s independence in 1947, the territory comprising Raigad district (then Kolaba) became part of the newly restructured Bombay State, formed from the former Bombay Presidency. After the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, Bombay State expanded to include Marathi-speaking regions from Hyderabad State, Vidarbha from southern Madhya Pradesh, and Saurashtra and Kutch in Gujarat. The state came to be known locally as Maha Dwibhashi Rajya (the great bilingual state) due to its inclusion of both Marathi- and Gujarati-speaking areas.

In 1956, the States Reorganisation Committee proposed the creation of a bilingual Maharashtra–Gujarat state with Bombay (now Mumbai) as its capital. The Samyukta Maharashtra movement, active during the 1957 elections, called for Bombay to be recognized as the capital of Maharashtra. On 1 May 1960, Bombay State was dissolved. Two new states were formed: Maharashtra, including Raigad and other Marathi-speaking areas, and Gujarat. Raigad has remained within Maharashtra State since that time.

Renaming of the District

In 1981, the district’s name was changed from Kolaba to Raigad. The renaming referenced the historical significance of Raigad Fort, a site closely associated with Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. The change took place during the tenure of Chief Minister A. R. Antulay, effective from 1 January 1981.

Alibag’s White Onion

In 2022, the white onion variety cultivated in Alibag received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag. This variety is identified by its white skin and flesh, distinctive flavor, and traditional methods of cultivation. The white onion of Alibag is noted for its specific taste and shape, which are attributed to the region’s geo-climatic conditions. The crop is grown from locally preserved seeds, and its reputation is based on long-standing agricultural practices in the area.

Sources

Aditi Shah. 2020. Elephanta Caves: Celebrating Shiva. Peepul Tree. https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Anita Kainthla. 2011. The Invincible Fort of Murud Janjira. India Currents.https://indiacurrents.com/the-invincible-for…

D. K. Vairagi. n.d. भर पावसातला चांभारगड, शेवते घाट आणी उपांड्या घाट. Maai Boli.https://www.maayboli.com/node/59421

Dhaval Kulkarni. Archaeological Survey of India excavates Raigad fort's pre-Maratha history. DNA India.https://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-archa…

Dr Uday Dokras, Srishti Dokras. n.d. Janjira Fort – Siddhi Architecture of India. Hypotheses.https://f-origin.hypotheses.org/wp-content/b…

East India Company. 1841. An Appeal to British Justice and Honour. The treatment of the protected native states of India by the Government of the East India Company, illustrated in the case of the State or Principality of Colaba, commonly called Angria's Colaba, near Bombay, in the East Indies. Smith, Elder & Company.https://books.google.com/books?id=R6pUWmpnSM…

Gayatri Desai. 2024. Study of Sea Fort Construction Techniques in Maharashtra. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ar-Gaya…

Indian Culture. n.d. The Legendary Raigad Fort. Indian Culture.https://indianculture.gov.in/forts-of-india/…

James M. Campbell. 1883. Gazetteer Of The Bombay Presidency: Kolaba District. Vol 11. Government Central Press.

Jewels of Maharashtra. 2017. Raigad Fort: The Capital of a Maratha Kingdom. Jewels of Maharashtra Blog. https://jewelsofmaharashtra.wordpress.com/20…

John O Brien. 2018. When British officials sought pensions for select residents of Colaba after annexing the region. The Scroll.https://scroll.in/article/890461/when-britis…

Kenneth X Robbins; John McLeod. 2006. African Elites in India: Habshi Amarat. New Delhi, India, Asia: Mapin.

Kurush Dalal. 2019. Chaul: Maharashtra's Medieval port. The Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1882 (reprinted in 2000). Thana District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Maharashtra Times. 2021. Chhatribagh of Angria in Alibaug.https://maharashtratimes-com.translate.goog/…

Manish Rai. 2014. Archaeology of Gharapuri (Elephanta) Island from Inscribed and Written Records.Heritage and Us. Vol 3, no. 3, ISSN 2319-1201.

Ministry of Culture. n.d. Destruction and burning of Raigad Fort. Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav. https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/district-reopsi…

Mumbai Tourism. n.d. Elephanta Island, Mumbai. Mumbai Tourism.https://mumbaitourism.travel/elephanta-islan…

Pavanpreet Kaur. n.d. Reimagining the Mahad Satyagraha in the Age of Google Maps. Critical Collective.https://criticalcollective.in/ArtistInner2.a…

Radhesyam Jadav. 2022. GI tag for Alibag’s white onion brings cheer to farmers. The Hindu.https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy…

S.S Puranik. n.d. Tulaji Angre Ek Vijaydurg - तुळाजी आंग्रे एक विजयदुर्ग. Sahyadri Books.

Shubhasree Purkayastha. 2019. Stories & Histories Hidden in Mumbai’s Suburbs. Sarmaya. https://sarmaya.in/spotlight/stories-histori…

Siddhartya Roy. 2016. The Lake Of Liberation. Outlook India. https://www.outlookindia.com/national/the-la…

Sohoni Pushkar. 2020. The Fort of Janjira. Greensboro, NC; Ahmedabad: University of North Carolina Ethiopian and East African Studies Project; Ahmedabad Sidi Heritage and Educational Center.

Swachhchandi. 2016. पेणचा वैभवशाली इतिहास - द. कृ. वैरागी. Maai Boli.https://web.archive.org/web/20081227211902/h…

TravelSole | Shash Wat. 2021. Unique Guide to Murud Janjira Fort. Medium. https://shash-wat2206.medium.com/unique-guid…

Websites Referred: Wikipedia, Raigad District: Official Website, Maharashtra Tourism: Hirakot Fort.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.