Contents

- Architecture of Prominent Sites

- Panhalakaji Caves

- Bankot Fort

- Karneshwar Mandir

- Gopalgad Fort

- Shahi Masjid

- Parshuram Mandir

- Murlidhar Mandir

- Thiba Palace

- Residential Architecture

- A Konkani House from the 1940s

- A Residence from the mid-20th Century on Guhagar Road

- A Residence from the 1960s on Chiplun-Karad Road

- A Residence from the 1980s in Markandi

- Sources

RATNAGIRI

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Ratnagiri’s architecture reflects a confluence of trade and layered religious traditions shaped by its coastal geography. The rock-cut Panhalakaji Caves in Dapoli span over a millennium of Buddhist, Shaiva, and Nath sect patronage carved into laterite cliffs. Coastal forts like Gopalgad and Bankot, first built under the Adil Shahis and Shilaharas, and later adapted by the Marathas and British, reflect shifting political control along maritime trade routes. Early Deccan mandirs such as Karneshwar Mandir feature basalt structures with iconographic variations, while the Murlidhar Mandir showcases localized adaptations to the Konkan climate. Sites like Parshuram Mandir exhibit syncretic styles blending Hindu, Portuguese, and Islamic elements, while Shahi Masjid in Dabhol shows Iranian influence with its egg-shaped dome. Thiba Palace, built in exile for Burma’s last king, blends colonial and Burmese architectural elements in laterite and teak.

Panhalakaji Caves

Panhalakaji Caves represent a multi-religious rock-cut architectural tradition carved into laterite cliffs along the Kotjai River in Ratnagiri district. Developed between the 3rd and 13th centuries CE, the site includes nearly 29 caves linked to Buddhist, Hindu, and Nath sect traditions, reflecting shifts in religious patronage and iconography over a millennium.

![The Panhalakaji Caves at Dapoli, Ratnagiri are excavated into laterite cliffs along the Kotjai River, featuring a range of rock-cut forms from Buddhist and Shaiva traditions.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/architecture/the-panhalakaji-caves-at-dapoli-ratnag_s49d9NV.png)

The earliest caves follow the Hinayana tradition of Buddhism, identifiable by simple stupas and austere forms. Later caves show Vajrayana influences and the presence of inscriptions in Brahmi and later Devanagari scripts further mark the site's evolving chronology.

From the 8th century onwards, during the Shilahara rule, several caves were modified or newly excavated for Shaiva and Nath Panth (Nath Panth, or Nath Sampradaya; it's a South Asian religious order primarily found associated with ascetic practices and yoga) use. Cave 14 features images of Nath figures like Matsyendranath and Gorakhnath. Cave 29, known locally as Gaur Lena, was associated with Nath ascetic practice. It houses a stone Shivling and contains Shaiva motifs on the ceiling.

The caves are hewn primarily into laterite rock and feature flat ceilings, plain columns, and occasionally carved door frames or iconographic panels. The architectural layout of most caves includes a central garbhagriha (sanctum) with an adjoining mandap (pillared hall), although this varies across the complex depending on the sectarian use.

![Stone pillars inside the Panhalakaji Caves show simple structural design typical of early Buddhist excavation, later adapted for Nath and Shaiva use.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/architecture/stone-pillars-inside-the-panhalakaji-c_nhvHJ17.png)

Bankot Fort

Bankot Fort is a coastal fortification in Bankot village, built in laterite and designed in a defensive style. The fort was known as Himmatgad under the Marathas and Fort Victoria under the British, reflecting its shifts in political control. The origins of Bankot Fort are believed to date back to the Shilahara dynasty (around the 10th to 13th Century), although the earliest documented reference appears in 1548, when the Portuguese are said to have captured and set fire to the fort and surrounding village.

![Aerial view of Bankot Fort and its surrounding landscape in Bankot village, Ratnagiri.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/architecture/aerial-view-of-bankot-fort-and-its-sur_QRcqXq6.png)

The fort’s layout is built for defense, featuring laterite walls around three ft. thick and a wide trench surrounding the structure. The main gate still stands, with remnants of a carved Bhagwaan Ganesh visible on the stone, a trace of the fort’s Maratha heritage. Within the compound are the remains of British-era bungalows, a well to the west, and a memorial to the wife and daughter of Officer Arthur Malt, who drowned at Bankot Khadi. A concealed sea-facing passage, known as the Chor Darwaja, may have been used for escape or discreet movement.

Karneshwar Mandir

Karneshwar Mandir is a stone-built structure reflecting early medieval Deccan mandir architecture. Located at the confluence of the Shashtri and Sonavani rivers in Kasba, Ratnagiri, it is dedicated to Bhagwaan Shiv and is among the oldest surviving mandirs in the region. Its construction is generally attributed to King Karn of the 11th-century Chalukya dynasty and is now a state-protected monument.

The Mandir is built primarily from dark basalt stone and features a sabhamandap (assembly hall) and mukhmandap (entrance hall), with stone carvings that reflect stylistic elements of medieval Indian iconography.

A prominent sculptural panel above the sabhamandap entrance shows Bhagwaan Vishnu in a reclining posture beneath a frieze of the Dashavatars. Interestingly, Devta Balram is shown as the eighth form instead of Krishna, a rare iconographic variation.

The pillars inside the sabhamandap are supported by horizontal Yaksha figures, functioning as bharvahaks (weight-bearers), both structurally and visually.

To the right of the eastern entrance is a magarmukh (crocodile-headed spout), used during abhishek rituals to channel offerings of milk or water. This spout reflects a local belief in the crocodile as Ganga’s vahan, with the flowing water treated as gangajal. The outer walls of the mukhmandap display ornamental stonework with figural and floral carvings typical of early Deccan mandir ornamentation.

Gopalgad Fort

Gopalgad Fort, also known as Anjaval Fort, is a coastal fortification constructed with laterite stone in a military style typical of the Konkan region. Located near Anjanvel village in Ratnagiri, the fort dates back to the 16th century, originally constructed under the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur. It occupies a strategic position at the junction of the Vashishti River, Dabhol Creek, and the Arabian Sea, overlooking maritime routes and trade points on the western coast.

![Aerial view of Gopalgad Fort showing laterite fort walls, gateways, and its strategic coastal placement near Anjanvel.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/architecture/aerial-view-of-gopalgad-fort-showing-l_z8KLSpx.png)

The fort is enclosed by laterite walls and features two main gates: an eastern gate bearing a Farsi inscription dated 1707, and a western gate facing the sea. Defensive features include a trench cut into the southern side of the fort and bastions positioned to guard against coastal attacks. The layout suggests a combination of residential and military functions, with the remains of a wada-style structure likely used for administrative or domestic purposes. The open courtyards and platform bases inside the fort indicate spaces for troop movement or temporary encampments.

Although now partially ruined, the surviving walls and foundation lines offer insight into typical Konkan coastal fort design, emphasizing visibility, access to water routes, and fortification against siege.

Shahi Masjid

Shahi Masjid in Dabhol follows Iranian architectural influence and was built in the 16th century. Locally known as the Anda Masjid due to its distinctive egg-shaped dome, the masjid is believed to be a replica of the Shahi Jama Masjid in Bijapur.

![External view of Shahi Masjid, Dabhol, showing its egg-shaped dome and corner minarets.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/architecture/external-view-of-shahi-masjid-dabhol-s_VCBn0BV.png)

The masjid is constructed from black stone and sits at the top of a wide flight of steps. Its entrance includes a fountain and an ablution basin. The facade features three large arches and four minarets placed at each corner. These minarets are simple but finely carved. The dome rises to a height of approximately 75 ft. and was once covered in gold leaf. Notably, the masjid has a central chhatri in front of the main dome and a symmetrical layout typical of Iranian-style masjids.

Parshuram Mandir

Parshuram Mandir in Chiplun follows a syncretic architectural style, combining Hindu, Portuguese, and Islamic influences. Located near the Mumbai–Goa Highway in Ratnagiri district, the Mandir was established around 1710 by Paramhans Shri Guru Bhramendra Swami. It is dedicated to Parshuram, the sixth form of Bhagwaan Vishnu, who is believed (according to regional lore) to have created the Konkan coast. The site holds deep religious and cultural significance. The Mandir’s architectural history is shaped by overlapping moments of regional patronage, Maratha associations, and reconstruction involving Portuguese artisans.

Architecturally, the Mandir displays a mix of styles. The black stone structure includes a laterite base, ornamental arches, and a modest shikhara (spire). The garbhagriha houses the murti of Parshuram, while smaller devasthans are found within the complex. The presence of features such as cusped arches and plaster detailing reflects Portuguese and Islamic stylistic elements layered onto a Hindu mandir plan.

The Mandir is located on the banks of the Vashishti River, offering a scenic view of the river and hills. It remains active for worship and draws visitors during festivals like Akshaya Tritiya, when the Mandir is decorated and ceremonies are held in reverence to Parshuram.

Murlidhar Mandir

Murlidhar Mandir reflects 18th-century local mandir architecture marked by the use of wood, carved detailing, and sloping tiled roofs. Built in 1780, it is located in Ratnagiri and is among the oldest surviving mandirs in the region. Though modest in scale, the structure offers insight into the spatial and material traditions of its time and continues to function as a site of regular worship.

The Mandir is approached by a short flight of stairs leading into a wooden sabhamandap, which is supported by carved wooden pillars and topped with a sloping roof made of mud tiles. The use of wood and tiles is typical of mandir construction in Konkan’s humid coastal climate, where lighter materials and sloped roofing help manage rainfall and humidity.

A stone deepmal (lamp tower) stands in the courtyard, lit during festive occasions. The Mandir’s preserved layout and unaltered materials reflect enduring architectural practices that remain closely tied to local religious life.

Thiba Palace

Thiba Palace follows a blend of colonial and Burmese architectural styles. It was constructed in 1910 as the residence of Thibaw Min, the last king of Burma, who was exiled and placed under house arrest here by the British. His queen, Supayalat, also lived at the site until he died in 1916.

Thiba Palace is built from red laterite and features a symmetrical three-storeyed layout. The structure includes teakwood beams, lava stone walls, and an exposed wooden roof. A central courtyard with a water fountain improves ventilation and reflects typical colonial design.

![A view of Thiba Palace, constructed in 1910 from red laterite, blending colonial and Burmese architectural styles.[6]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/architecture/a-view-of-thiba-palace-constructed-in-_AveRcSU.png)

Key architectural details include semicircular wooden windows inspired by Burmese stupas, arched openings for lighting and airflow, and a marble-floored hall used for performances. Peripheral corridors and a concealed staircase used by the royal family are also part of the layout. A Buddhist murti placed at the rear adds to the palace’s Burmese architectural elements.

Residential Architecture

In Ratnagiri district, domestic architecture reflects a deep-rooted engagement with time (both seasonal and historical). Residences across the region, from the 1940s Konkani homes to mid-20th-century structures in Chiplun, are shaped by agricultural rhythms, climatic needs, and evolving social norms. These houses often feature sloping roofs with terracotta or mud tiles, stone or laterite plinths, and mud-plastered walls—all drawing on local materials for thermal comfort and durability. Spatial arrangements, such as the presence of a vadi for cultivation or an attic for grain storage, show how households integrated food production into the very fabric of daily life. Elements like the balintinichi kholi (a dedicated room for menstruating or pregnant women), clerestory windows, and inward-opening shutters offer insights into how domestic spaces adapted over time to both private rituals and communal exchanges. With renovations spanning decades, these homes embody not just continuity but the layering of lived experiences: reimagining time through material memory and incremental change.

A Konkani House from the 1940s

Ratnagiri district is home to several settlements where built structures are closely integrated with agricultural practices and the natural landscape. In one such settlement, this one-storey residence, built around the mid-1940s, sits at the centre of a rectangular plot. The front yard features flowering shrubs and seasonal vegetables, while the backyard, locally known as the vadi, is used for cultivating coconuts, supari, and beans. Most houses in the area have a well in their vadi, supplying fresh water for domestic use. The village streets, locally referred to as chirache raste, are traditionally paved with laterite red stones, lending a distinct visual and cultural identity to the settlement.

The plinth of the house is built using stone masonry. The composite structure features locally available materials: cow dung was traditionally used to coat the floor, while the walls are constructed with red sandstone and finished with a layer of red mud plaster. Red sandstone was chosen for its thermal properties, helping to keep the house cool. The sloping roof is covered with terracotta tiles, which also aid in temperature regulation.

The doors of the house are made out of wood. The doors are wooden panel doors, with a wooden frame and iron embellishments.

The windows of this house are fitted with metal grills with shutters that open inward. Unlike the other windows around the house, the ones beside the main door do not have panel shutters. This design choice allows for maximum natural light and airflow into the interior spaces.

The house also features a ‘balintinichi kholi’ (literally translated as the delivery room), a room traditionally used by menstruating and pregnant women, offering insight into the social practices and domestic arrangements of the time. The room includes a small built-in bathing space and an external drain for water disposal.

The attic, traditionally used to store surplus agricultural produce, features a wooden floor and mud-plastered walls and has visible rafters of the sloping roof.

A Residence from the mid-20th Century on Guhagar Road

The Guhagar road runs through Markandi, a settlement in Chiplun, located in the Ratnagiri district. It is an area known for its dense greenery and laterite-rich terrain. Along this road stands a one-storey house, estimated to have been built around the 1950s or 60s. Set back from the main road, the residence is surrounded by trees in its front and backyards, offering shade and quiet seclusion.

The exterior of the house is painted in a faded pink tone, with a small attic on top featuring exposed brickwork. A narrow walkway leads from the road to the entrance of the house, where the residents have parked their two-wheelers.

Constructed in the mid-20th century, the house was renovated in 2014 and 2021. The composite structure of the house is composed of cement, laterite rock, and black basalt rock (for the foundation). The roof is constructed using a wooden frame and topped with mud tiles. The exterior walls are painted in a neutral, faded pink shade, while the interior walls carry a cool white tone, lending a subtle contrast to the earthy materials used in the structure.

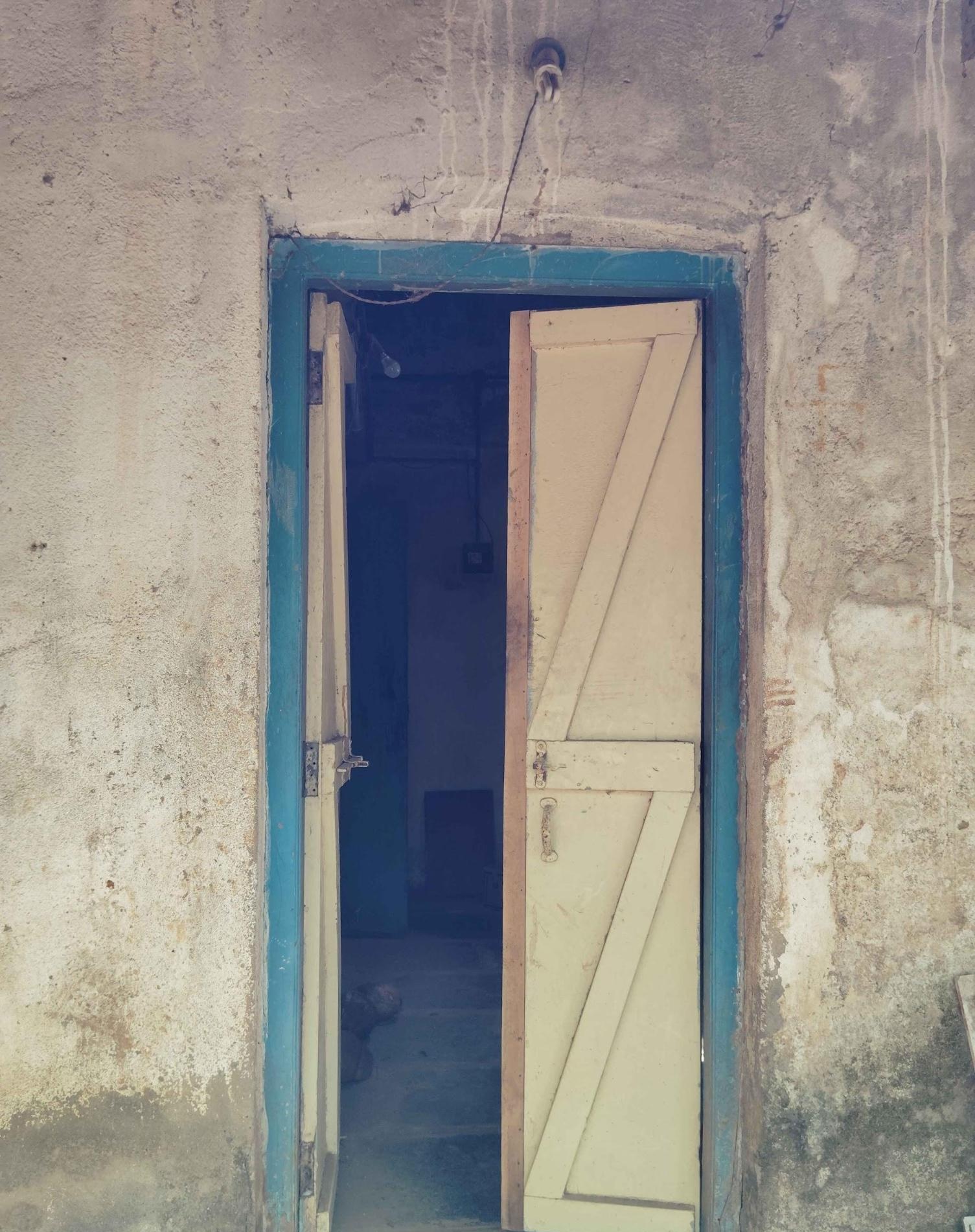

The designs on the doors in the house are distinctive. They are double-shuttered and feature a zigzag pattern, seen both on the door leading to the backyard and on the door in the living room that opens into one of the inner rooms. Just beside the main entrance, a small shoe stand has been kept—a common feature in homes across the region.

All the windows around the house have a similar structure, while the colors may differ. They are wooden and have double shutters that open outwards and have metal grills. The windows also have an upper clerestory window above with glass panes to let in light.

The windows of the dining room can be seen next to the door at the entrance of the house. The color of the windows around the house differs and corresponds to where they are positioned in the house. The windows of the dining room are a neutral white color, while those of the storeroom, situated at the back of the house, are blue.

A wall composed of laterite rock and cement, built in 2021-22, encircles the compound. The wall was built as part of the second renovation of the house.

The house has a backyard where several mango trees grow. These trees bear Alphonso mangoes, a variety native to the Konkan region and particularly associated with Ratnagiri. Known for their distinct sweetness and aroma, Alphonso mangoes are among the most valued mango varieties in the region.

A wooden staircase within the house provides access to the attic above.

The roof of the attic features exposed wooden rafters that reveal the underlying structural framework of the house. This wooden framework is evidence of traditional construction techniques, probably typical of the time period it was built in. The attic floor is also made entirely of wood.

A Residence from the 1960s on Chiplun-Karad Road

The building is located near Bahadur Shaikh Naka, along the Chiplun-Karad road. It is a mixed-use structure, with one room at the front converted into a small garment and tailoring shop, and the rest of the house is a private residence.

The house is situated on the Subhash Road in Ratnagiri, with exterior walls painted a neutral tone. It is a single-storey structure topped with an attic-like space, with cement making up its composite structure. It was built around the late 1960s, reflecting construction methods in use at the time.

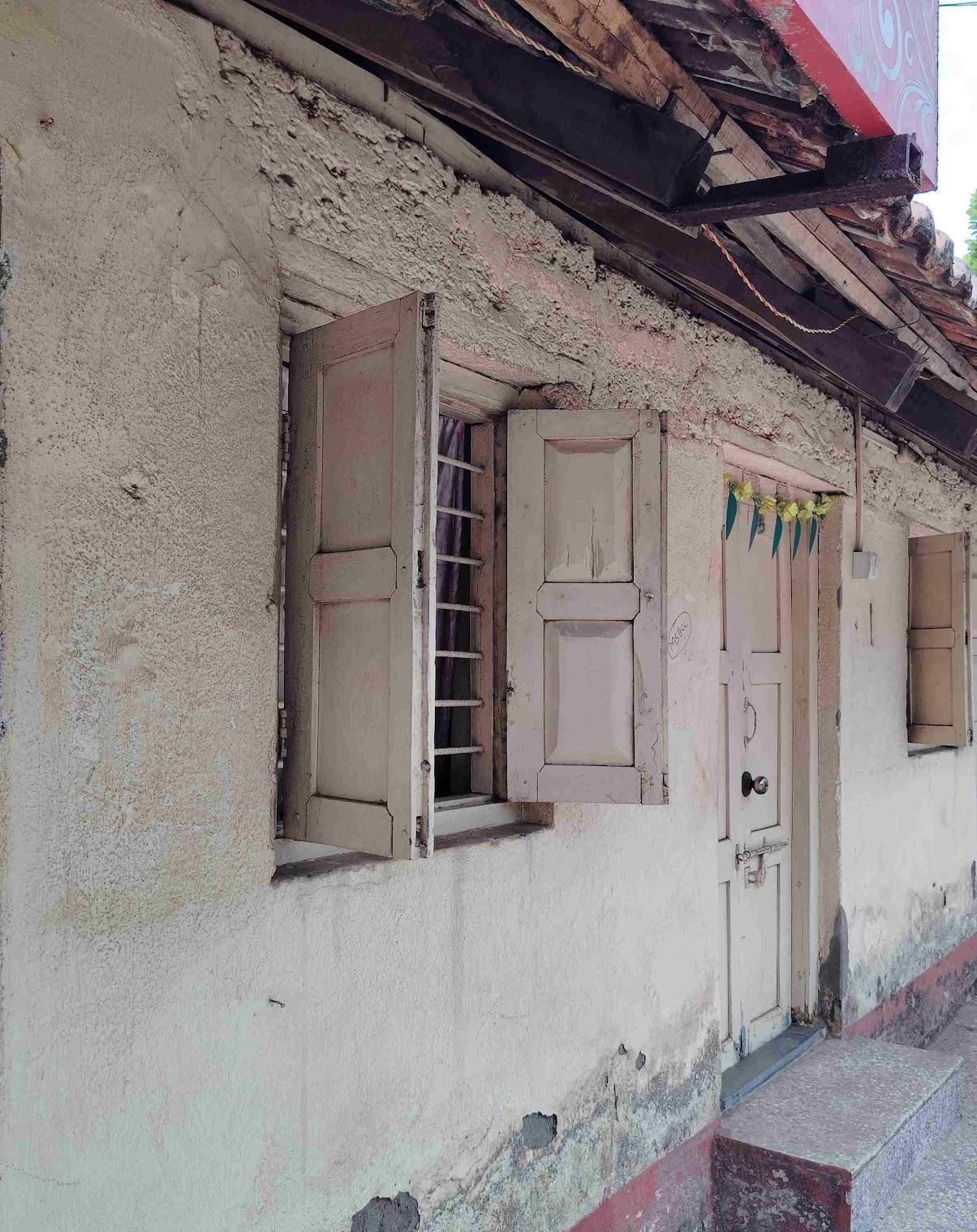

The door of the house is of medium height and slightly elevated, with a short staircase leading up to it. It is a double-panelled wooden door featuring a hatch lock and handle, and next to it is an electric doorbell. The door is adorned with a toran (a decorative hanging placed at the entrance of a house, traditionally believed to attract prosperity to the family residing within) made of plastic, yellow flowers, and mango leaves.

The windows of the house are relatively small and fitted with spaced horizontal grills. Each window has two wooden shutters that open outward. The design of the shutters mirrors that of the main door. There are two such windows on the front of the house, positioned on either side of the door.

The roof of the house is a sloping structure covered with traditional mud tiles.

The house has a well-maintained garden with lush green trees and healthy plants.

A Residence from the 1980s in Markandi

Markandi, a locality in Chiplun city in the Konkan region of Maharashtra, is known for its mix of residential and commercial spaces. The area accommodates a range of middle-class to well-off families and has various types of shops. The locality also lies within walking distance of The United English School, established in 1918. In this locality, just off the main Karad–Chiplun road, an internal lane leads to this two-storey residence, built around the mid-1980s.

The exterior of the building features exposed brickwork, while the interiors are painted in a variety of colors, each adding a distinct pop of brightness to the space. The house has a composite structure primarily made of cement, with a sloping roof covered in traditional mud tiles.

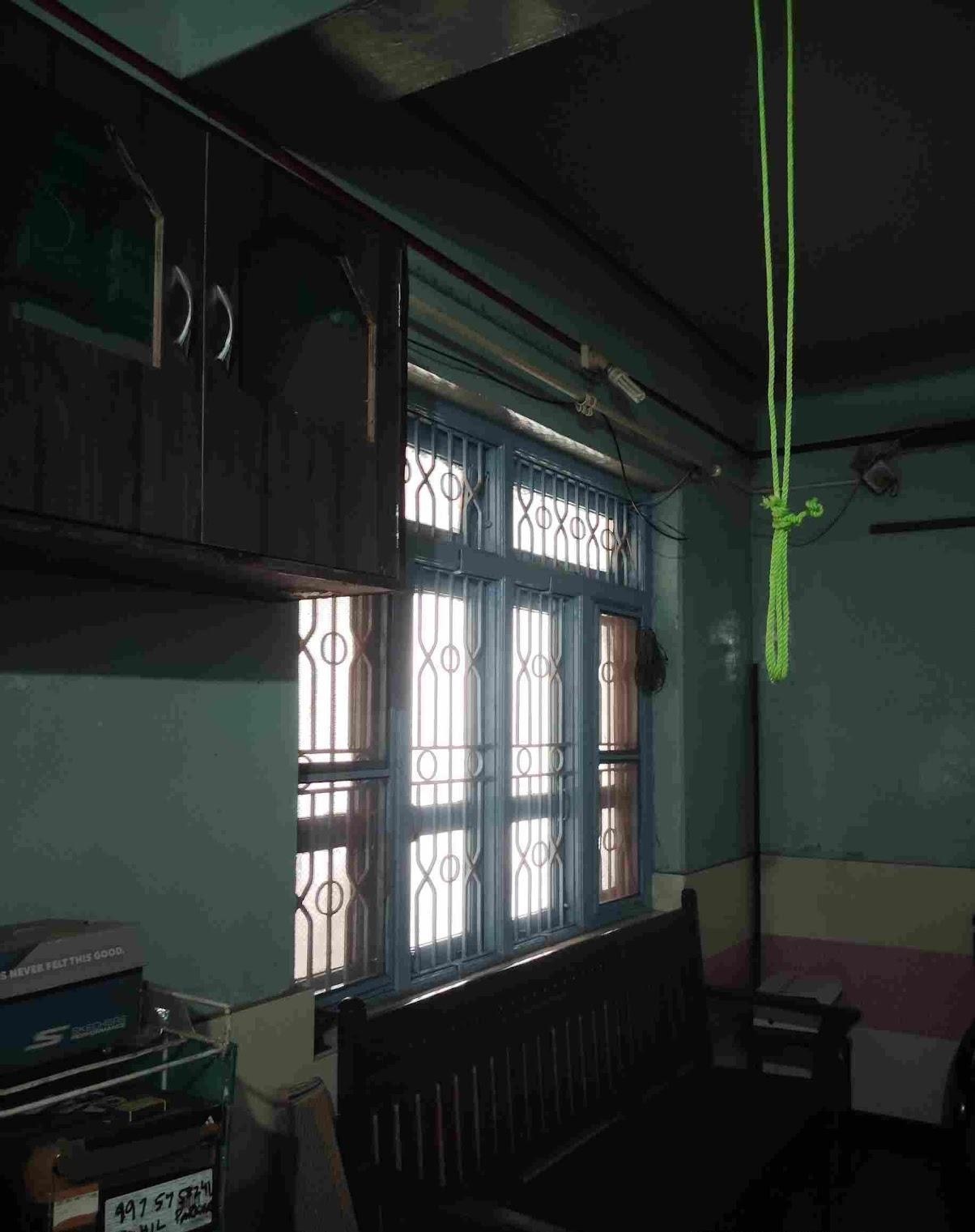

At the entrance of the house is a blue double-paneled wooden door, while a grey one with green-bordered squares stands along the hallway leading to the hall. Both doors are wooden and double-paneled. Above each is a small clerestory vent with a mesh covering, allowing light and ventilation into the space.

The windows are fitted with metal rods arranged in a specific decorative pattern, and each has a metal frame with glass panes. A long window along the stairwell wall, leading to the first floor, features horizontal metal rods.

The house has two staircases leading to the upper storey. The inner staircase is constructed from cement, with mud tiles on the steps and a cement railing. The outer staircase is made of iron, with a matching iron railing.

The house has a spacious attic supported by thin wooden beams, with visible rafters lining the sloping roof. The flooring in the attic is finished with cement.

The house has a sloping roof made of mud tiles.

Sources

Dongarmatha. The Parshuram Temple in Chiplun. Dongarmatha.https://www.dongarmatha.com/the-parshuram-te…

Kirthika Nandhakumar. 2020. Thiba Palace: The Remnant of Myanmar’s Royal Family in India. Pratha: The Indian School of Cultural Studies.https://www.prathaculturalschool.com/post/th…

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1880 (reprinted in 1996). Ratnagiri and Sawantwadi District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Sachin Vidyadhar Joshi. 2012. रत्नागिरी जिल्ह्याची दुर्गजिज्ञासा. Bookmark Publication. Parag Pimpale. 2004. Sad Sagarachi: Guhagar-Velneshwar-Hedavi. Bookmark Publication.

Taluka Dapoli. 2018. Shahi Masjid, Dabhole. Taluka Dapoli.https://talukadapoli.com/places/shahi-masjid…

Wikipedia Contributors. 2025. Panhalakaji Caves. Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panhalakaji_Ca…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.