Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Bhagwan Ram and the Sangameshwar Mandir

- Sangli as part of Kuntala

- Satavahana Period and the Buddhist Caves at Kukatoli

- Vishnukundins and Khanapur

- Jain Heritage and the Chalukyas of Badami

- The Shilaharas of Karad & their Land Grant at Miraj

- Epigraphic Records from the Late Chalukyas

- Medieval Period

- Miraj Under the Bahmanis

- The Durgadevi Famine (1396–1407 CE)

- Administrative Shifts and the Relocation of the Bahmani Capital

- Mahmud Gawan and the Centralisation of Power

- The Decline of Bahmani Rule and the Rise of Yusuf Adil Khan

- The Campaign Against Bahadur Gilani and the Capture of Miraj

- Political Unrest and Regional Struggles

- Chand Bibi and the Crisis of Regency in the Bijapur Sultanate

- The Daphle family and Feudal Lineages of Maratha Chiefs in Sangli

- Mughal Campaigns in the Deccan

- The Daphlapur State

- Power Struggle between the Marathas and Mughals

- Miraj under Mughal Rule

- The Decline of Mughal Power and the Rise of the Marathas

- Patwardhans of Sangli

- Division of Estates & the Founding of the Sangli State

- The Treaty of Pandharpur (1812) and British Recognition

- Colonial Period

- The Sangli State and the Rule of Chintamanrao I (1782–1851)

- Reforms and Joint Administrative during the reign of Dhundirav Chintamanrao (r. 1851–1901)

- Regency and Administration under Chintamanrao Dhundirav Patwardhan (r. 1901–1947)

- Jath and Daphlapur under British Rule

- Kirloskarwadi and Industrial Enterprise

- Artisanal Production of Musical Instruments in Miraj

- Peasant Movement in Miraj

- Political Developments in Sangli State

- The Jungle Satyagraha in Kavathe

- The Armed Resistance of Veera Sindhura Lakshmana

- Nagnath Naikwadi and the Prati Sarkar

- Women’s Participation in the Freedom Movement

- Post-Independence

- Turmeric Production and Its Commercial Expansion

- Sources

SANGLI

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

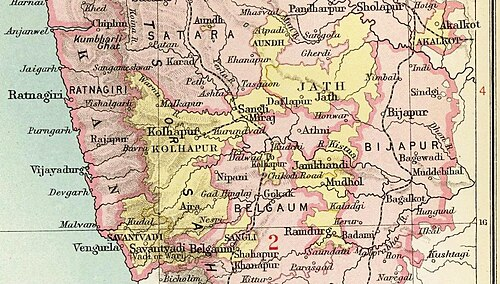

Sangli district, located in the southern part of Maharashtra, lies along the course of the Krishna River and has historically occupied a position on key inland trade routes in the Deccan. This geographic setting contributed to its early development as a centre of local commerce and administration.

The region came under the control of the Maratha Empire in the 17th century and remained under Maratha authority until the early 19th century, when, in the aftermath of the Anglo-Maratha Wars, parts of it passed into British hands. A considerable portion of present-day Sangli was governed as princely states, including those ruled by branches of the Patwardhan and Daphle dynasties. These states, such as Sangli, Miraj, and Tasgaon, remained under British suzerainty until 1947, when they were integrated into the Indian Union. Until May 1960, the area was known as South Satara, reflecting its earlier inclusion within the broader Satara district. It was reorganised and renamed Sangli following the creation of Maharashtra State.

Etymology

The name Sangli is commonly believed to derive from an earlier form, Sahagalli, a compound of the Marathi words saha (six) and galli (lanes). The name is said to refer to the original layout of the principal town, where six narrow streets are thought to have converged. In the course of local usage, the form was shortened to its present version.

Ancient Period

Bhagwan Ram and the Sangameshwar Mandir

One of the earliest traces of Sangli’s early history is tied to traditions related to the Ramayan. According to local belief, during the period of Bhagwan Ram’s exile, he is said to have passed through the area now known as Haripur, approximately five kilometres southwest of present-day Sangli. At the confluence of the Krishna and Warana rivers, he is believed to have consecrated a Shivling, shaped with his own hands. Devotees maintain that faint impressions on the stone preserve the marks of his fingers.

The Mandir that stands at this site today is known as the Sangameshwar Mandir, with its name derived from this meeting of rivers (which literally means sangam in Marathi). It continues to hold much significance even today.

Sangli as part of Kuntala

The territory that now forms Sangli district has, at various times, fallen under the authority of different kingdoms. Its early history is difficult to reconstruct in full due to the scarcity of written records and limited archaeological investigation. However, archaeological findings and scattered references in literary sources allow for a tentative outline.

During the early historical period, the Deccan was divided into several regional units known by distinct names. Among these, Kuntala is recorded as a prominent division extending across portions of what are now southern Maharashtra and northern Karnataka.

According to the district Gazetteer (1969), the districts of Kolhapur, Satara, Solapur, and Sangli were once included within the wider boundaries of Kuntala. Inscriptions cited by Mirashi indicate that the upper valley of the Krishna River was regarded as part of this region. As Sangli lies within this geographical corridor, its inclusion in Kuntala may be possible.

Satavahana Period and the Buddhist Caves at Kukatoli

Among the earliest dynasties to establish rule over this part of the Deccan were the Satavahanas, whose dominion extended, at various times between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE, across large portions of the plateau. The area corresponding to the modern Sangli district appears to have formed part of the southern dominions of the Satavahanas. It is important to note that this period witnessed a notable extension of Buddhist religious architecture, particularly in the form of rock-cut cave sanctuaries, many of which were constructed under royal or merchant patronage.

Recent findings near the Girling Hill in Sangli lend substance to the view that Buddhism had gained a footing in this region during the Satavahana Period. Several rock-cut caves, characteristic of the early Hinayana tradition, have been identified by researchers affiliated with the Miraj Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal, in collaboration with academic personnel from Satara. These structures, tentatively dated to the 1st century CE, constitute the earliest material evidence of Buddhism within the Sangli district.

The distribution of these caves in the district is noteworthy. Four are situated near the village of Kukatoli in Kavathe-Mahankal taluka, while two additional sites have been recorded at Belanki and Kadamwadi, both in Miraj taluka. The separation of these sites by distance, coupled with their alignment across the slopes of the Girling Hills, suggests that they may have formed part of a monastic network positioned along a local trade route or pilgrimage corridor. What is of particular note, that many scholars say that no similar cave sites had hitherto been documented in the district and this may be taken to suggest that this part of the district once stood upon a line of transit frequented by both religious and mercantile communities during the early historical period.

Vishnukundins and Khanapur

Following the decline of the Satavahanas, political authority in the Deccan underwent several realignments. The Vakatakas succeeded them in certain quarters, though their control appears not to have extended in any sustained manner over the Sangli region. In time, the Vishnukundin dynasty advanced westward and is believed to have briefly held sway over parts of southern Maharashtra.

A copperplate grant of this dynasty, discovered at Khanapur, now a taluka headquarters in Sangli district, constitutes one of the earliest known epigraphic records from the region. The inscription refers to a land grant concerning the village of Retturaka, generally identified with modern Rethare Budruk, and attests to the administrative presence of the Vishnukundins in this region during the 5th or 6th century CE.

Jain Heritage and the Chalukyas of Badami

Between the 6th and 8th centuries CE, the Chalukyas of Badami extended their authority across much of the western Deccan. During their rule, Sangli appears to have been a centre of Jain religious activity. Caves at Kundal, a village in the district, contain a shrine associated with Rishabhanatha, the first Tīrthaṅkara of Jainism. These remains point to an established Jain presence in the region during this period.

The hill above Kundal is known as Samav Sharan, and is regarded by Jain tradition as a site where Mahaveer, the twenty-fourth Tīrthankara, delivered sermons. While such beliefs are devotional in nature, the continued reverence of the site reflects the longstanding importance of Kundal to the Jain community.

The Shilaharas of Karad & their Land Grant at Miraj

Between 1050 and 1220 CE, Sangli district came under the authority of the Shilaharas of Kolhapur, often referred to in inscriptions as the Shilaharas of Karad. Their early capital was situated at Karad (in present-day Satara district, Maharashtra), from which they extended their influence southward.

A copper-plate grant discovered at Miraj (now the headquarters of Miraj taluka, Sangli district) confirms their administrative control in this part of the Krishna River valley. Additional corroboration appears in Bilhaṇa’s Vikramankadevacarita, a courtly biography of the Western Chalukya ruler Vikramāditya VI, which refers to the Shilahara ruler Raja Gonka as governing Karad, Miraj, and parts of the Konkan coast.

The Shilaharas are credited with the construction of several forts in the region, strategically positioned across the upper Krishna basin and adjoining hill country, many of which were later enlarged or rebuilt by subsequent dynasties.

Epigraphic Records from the Late Chalukyas

The 11th and 12th centuries CE saw the emergence of the Later Chalukyas, also known as the Chalukyas of Kalyani (modern Basavakalyan, in Bidar district, Karnataka), as a dominant power in the western Deccan. Their presence in the region, now comprising Sangli district, is confirmed through several epigraphic records discovered in and around the area.

Among the earliest of these are two copperplate grants dated to the 11th century, which provide insight into the administrative framework of the Later Chalukya state and its practice of religious endowment. One of the more recent finds is an inscription at the Sangameshwar Mandir in Haripur (in Khanapur taluka, Sangli district), which further affirms the dynasty’s influence in this region. Notably, the Mandir is dated to this period, and remnants of architecture survive within its structure.

The Later Chalukyas are well known for their patronage of temple construction, and their inscriptions frequently record land or revenue grants for the maintenance of shrines. In Sangli district, such activity was not confined to Haripur alone. Notably, the town of Miraj, today the administrative headquarters of Miraj taluka, is referred to in epigraphic sources as the head of the “Mirinje” division, a local unit of governance under the Chalukyan system.

Further evidence of Chalukya presence has been uncovered at Ankalkhop, a village situated in Palus taluka, on the right bank of the Krishna River, approximately 24 km north of Sangli city and 7 km northeast of Palus. A stone inscription recovered at this site is dated to the 12th or 13th century CE and likely corresponds to the later phase of Chalukya rule.

By the close of the 12th century, the authority of the Later Chalukyas had declined across much of the Deccan. Their place was taken by the Yadavas of Devagiri (modern Daulatabad, in Sambhaji district), who came to dominate the Deccan region. The district likely remained under Yadava control until the early 14th century, at which point it was incorporated into the expanding dominions of the Delhi Sultanate.

Medieval Period

The 14th century CE marked a decisive shift in the political history of the wider Deccan region. The Delhi Sultanate nominally extended its authority into the region in the early part of the century, but its control was neither uniform nor uncontested. By 1347 CE, their influence declined with the establishment of an independent Deccan Sultanate under Zafar Khan, later styled Bahman Shah, who founded the Bahmani Sultanate with its capital at Gulbarga (modern Kalaburagi, Karnataka). This event brought Sangli within the expanding dominions of the Bahmani state.

Miraj Under the Bahmanis

The incorporation of the Sangli region into the Bahmani Sultanate was of particular consequence for Miraj (now a city in Sangli district), which emerged as a site of military and administrative importance. Historical accounts record that in 1347 CE, Miraj was captured by Hasan Bahman Shah, the founder of the Sultanate himself. In commemoration of this victory, the area was said to have been renamed Mubarakabad.

The Miraj Fort, positioned on elevated ground near the Krishna River basin, served as a strategic garrison. Its location made it a key defensive site for controlling access routes into southern Maharashtra. The Sangli District Gazetteer (1969) notes that the Sultan resided in Miraj on occasion, underlining its importance within the Bahmani military system. The concentration of troops and administrative function at Miraj likely imposed a considerable strain on local resources, especially during prolonged campaigns.

The period also coincided with a transformation in the art of warfare, marked by the growing deployment of gunpowder and artillery in South Asia. The Bahmani rulers, like their contemporaries elsewhere, responded to this innovation by constructing and strengthening fortifications. Many of the forts in Sangli district are believed to have been either built or significantly reinforced during this time to resist the destructive capabilities of early cannon fire.

Beyond military concerns, the Bahmanis implemented an organised administrative system. The Sultanate was divided into four principal divisions (tarafs), each under a provincial governor. Sangli, during this period, formed part of the Gulbarga division, which comprised much of the northern Deccan.

The Durgadevi Famine (1396–1407 CE)

The stability established under early Bahmani rule was severely tested during the Durgadevi famine, which afflicted much of the Deccan plateau between 1396 and 1407 CE. Sources cited in the district Gazetteer describe entire settlements becoming deserted, with nearby regions such as Solapur suffering near-total abandonment. Sangli likely experienced similar patterns of village desertion and fort abandonment.

Relief efforts were attempted by the Bahmani court, including grain imports from Gujarat and assistance to orphaned children, but the scale and duration of the crisis overwhelmed administrative capacity. The famine abated only after the return of regular monsoons in 1429 CE, by which time considerable social and economic dislocation had occurred.

Administrative Shifts and the Relocation of the Bahmani Capital

Under Ahmad Shah I Wali (r. 1422–1458), the Bahmani capital was transferred from Gulbarga to Bidar, altering the administrative geography of the sultanate. This reorientation may have affected the governance of the Sangli region, though it remained within the Gulbarga taraf. Reports of continued hardship, including famine and unrest, appear in literary sources from this period.

Efforts to resettle depopulated villages included the grant of tax-free land for one year and state-provided grain in the second. These policies reflected the state's attempt to restore agricultural output and stabilise rural societies.

Mahmud Gawan and the Centralisation of Power

The latter half of the 15th century saw the ascendancy of Mahmud Gawan, a Persian-born vizier who played a pivotal role in reforming the Bahmani administration. His tenure was marked by campaigns aimed at expanding the sultanate’s territory, as well as curbing the power of local governors, reforms that directly impacted regions like Sangli, where provincial fort control had become a point of contention.

Among Gawan’s key measures was a directive that each governor be allowed control of only one fort, with all others placed under the command of royal officers. This centralised military control likely extended to key forts in the Sangli tract, such as those at Miraj, Tasgaon, and Palus, many of which had strategic value for riverine and overland routes.

While these policies strengthened the state, they provoked resentment among the nobility, leading to Gawan’s execution in 1481 CE, after which governors resumed their autonomy in the western Deccan.

The Decline of Bahmani Rule and the Rise of Yusuf Adil Khan

The decline of the Bahmani Sultanate following the execution of its minister Mahmud Gawan in 1482 CE opened the way for ambitious governors to assert independence. Among these was Yusuf Adil Khan, the governor of Daulatabad, who emerged as a principal figure in the western Deccan.

By 1489 CE, Yusuf is believed to have declared his independence, though the precise timing is a matter of some debate. The historian Ferishta states that the khutba (Friday sermon) was read in Yusuf’s name in that year, a traditional marker of sovereignty. However, Dr. Haroon Khan Sherwani notes that coins and inscriptions from the period continued to bear the name of the Bahmani rulers, suggesting that the break with the old regime was gradual rather than immediate.

It was during this phase of political fragmentation that the Bijapur Sultanate began to take shape, with Yusuf Adil Khan at its head. The territory now forming Sangli district, situated in the Krishna basin, would soon fall within its domain.

The Campaign Against Bahadur Gilani and the Capture of Miraj

In the years following his declaration of independence, Yusuf Adil Khan turned his attention to consolidating control over adjacent territories. At this time, Miraj, a fortified settlement of strategic importance, was under the control of Bahadur Gilani, a former Bahmani officer who had established his own authority in the region.

At the request of the nominal Bahmani Sultan, Yusuf marched against Gilani. Historical accounts record that he encamped at Miraj during this campaign.

Gilani rejected the terms of submission and was ultimately defeated in 1494 CE. With his defeat, Yusuf brought Miraj and the wider Sangli region under his control, securing the western frontier of the Bijapur state. From this period onward, Sangli remained within the domain of the Adil Shahi dynasty, lying between the rival powers of Ahmadnagar to the north and Vijayanagara to the south.

Political Unrest and Regional Struggles

The 16th century appears to have been a turbulent period for the Bijapur Sultanate and was marked by repeated conflicts with neighbouring states and intermittent instability within. The Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar to the north and the Vijayanagara Empire to the south posed continual challenges to Bijapur’s frontiers, and Sangli, situated along this borderland, often became drawn into these wider struggles.

During the reign of Ibrahim Adil Shah I (r. 1534–1558), the sultan suffered a military defeat at Solapur at the hands of Hussain Nizam Shah I of Ahmadnagar. In the aftermath, Ibrahim dismissed his general, Saif-ain-ul-Mulk, from service. The disgraced commander withdrew to Man (in present-day Satara district) and soon began asserting independent authority in the region.

From his base at Man, Ain-ul-Mulk began to collect revenue without sanction, first in his immediate surroundings and eventually in neighbouring regions, including Miraj, which lay within Sangli territory. His growing influence posed a direct challenge to Bijapur’s authority in the western Deccan. Though initially successful in resisting royal forces sent against him, Ain-ul-Mulk’s ambitions provoked a more determined response.

With the assistance of Vijayanagara, Ibrahim Adil Shah mounted a campaign to subdue Ain-ul-Mulk, and he was eventually defeated, and the Sultanate reasserted control over the affected regions.

Chand Bibi and the Crisis of Regency in the Bijapur Sultanate

The latter half of the 16th century saw renewed internal unrest following the death of Ali Adil Shah I. His successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah II, ascended the throne as a minor, leading to a prolonged period of regency and factional politics. Several powerful nobles vied for influence, and amidst this uncertainty, Chand Bibi, the dowager queen, rose as a formidable figure in court politics.

Her authority, however, was contested by competing factions at court. One such rival, Kiswar Khan, succeeded in placing Chand Bibi under house arrest at Satara Fort, seeking to eliminate her influence over the young Sultan. His control was short-lived; he was later overthrown by opposing nobles, and Chand Bibi was restored to political prominence.

In 1594 CE, Prince Ismail, a member of the Adil Shahi family, led a rebellion against the regency. He was supported by Ain-ul-Mulk, a former Bijapur commander who had previously fallen out of favour but still retained influence in the Deccan. Their insurrection was viewed as a direct threat to the fragile regency.

In response, Bijapur forces under the command of Hamid Khan were dispatched to suppress the revolt. Ain-ul-Mulk was captured and is said to have been brought to Miraj.

The Daphle family and Feudal Lineages of Maratha Chiefs in Sangli

Throughout the Adil Shahi period, several Maratha families rose to prominence through their service to the Sultanate of Bijapur. Among these, the Daphles of Jath, located in the southeastern corner of the present-day Sangli district, held a particularly influential position.

The Daphles, originally bearing the surname Chavhan, derived their title from the village of Daphlapur (which lies in the Jath taluka of the present-day Sangli district), where they held the hereditary office of patil (village headman). Their ascent began under the reign of Ali Adil Shah I, during which Lakhmajirao Yeldojirao Chavan entered royal service and was granted a deshmukh watan, a hereditary land revenue assignment covering four parganas.

In time, the family was entrusted with military command, becoming key figures in Bijapur’s frontier administration.

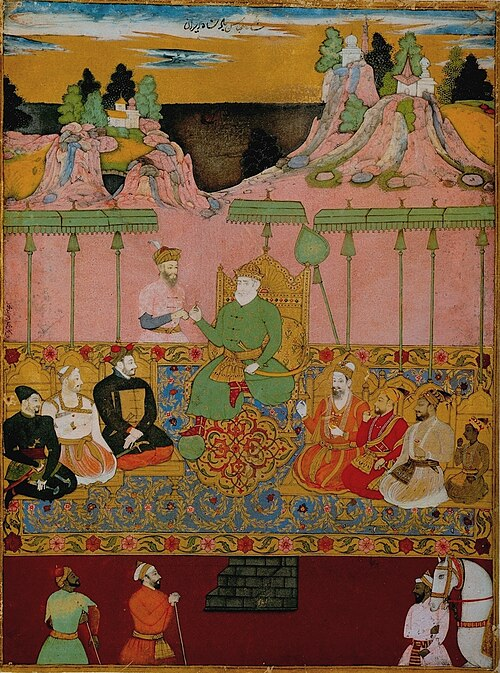

Mughal Campaigns in the Deccan

In the late 16th century, the Mughal Empire extended its authority southward into the Deccan. The initial incursion occurred under Emperor Akbar in 1593 CE, when efforts began to bring the Deccan Sultanates under Mughal control. The campaigns intensified under Shah Jahan, whose forces inflicted significant damage upon the territories of the Bijapur Sultanate, one of the principal Deccan states.

To counter this threat, the rulers of Bijapur entered into a temporary alliance with the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, ceding certain jagirs in the process. Among these was Khanapur, now a village in Sangli district, which passed under Nizam Shahi control. Although a treaty was eventually signed, compelling Bijapur to pay tribute to the Mughals while receiving a portion of the Ahmadnagar territory in return, this settlement proved short-lived. Mughal ambitions in the Deccan continued unabated, drawing the region into prolonged conflict that would shape its political trajectory well into the 18th century.

The Daphlapur State

Amidst this broader backdrop of contestation, local chieftains in the Deccan gradually consolidated their authority. Among them were the Daphles of Jath, a Maratha family who had served the Adil Shahi state in both administrative and military capacities. By the second half of the 17th century, the family had transitioned from subordinate military commanders to de facto autonomous rulers.

In 1672 CE, Satvaji Chavan, a descendant of the original Daphle lineage, is said to have founded the Daphlapur State, centred around the family’s hereditary lands, many of which lay in Sangli district. Although their position shifted under Maratha and later British oversight, the Daphles retained considerable influence in the region well into the colonial era.

Power Struggle between the Marathas and Mughals

Parallel to the Mughal push into the Deccan, the rise of the Maratha Confederacy under Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj reconfigured the political landscape. Initially, Shivaji sought accommodation with the Mughals, offering his assistance to Prince Aurangzeb, then viceroy of the Deccan, in return for formal recognition of his control over forts and territories seized from Bijapur. When his overtures were rebuffed, and Bijapur offered more favourable terms, Shivaji turned against the Mughals, launching a series of raids into their Deccan holdings beginning in 1657 CE.

His campaigns continued until he died in 1680, leaving the region, including Sangli district, exposed to ongoing warfare. Under his son Chhatrapati Sambhaji, the Maratha resistance persisted, successfully holding the Mughals at bay until 1686, when Aurangzeb launched a major offensive into the Deccan. During this campaign, the Mughals succeeded in capturing Miraj and other parts of the present-day Sangli district.

Miraj under Mughal Rule

Following its conquest, Miraj (then known as Murtazabad) was incorporated into the Mughal administrative system. According to the Sangli district Gazetteer (1969), by the time of Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Deccan had been reorganised into six subhas (provinces): Khandesh, Berar, Aurangabad, Bidar, Bijapur, and Hyderabad.

Miraj formed part of the Bijapur province, which included additional districts such as Akluj (now in Solapur), Raibag (Belgaum), Naldurg (Dharashiv), Dabhol (Ratnagiri), and Panhala (Kolhapur). It served as the district headquarters, divided into six talukas and comprising 225 villages. The total monthly revenue of the Miraj district was estimated at Rs. 5,57,359, translating to an annual income exceeding Rs. 11 lakh.

The Decline of Mughal Power and the Rise of the Marathas

Following Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Mughal Empire rapidly lost its hold over the Deccan. The vacuum was filled by competing Maratha factions, each vying for control over the former imperial provinces. In this struggle, Shahu I, grandson of Shivaji, emerged as the dominant claimant. He ultimately defeated his rival Tarabai, who had ruled from Panhala, and was crowned Chhatrapati at Satara, thus re-establishing a centralised Maratha authority in the early 18th century.

During this period, Sangli district found itself caught between shifting allegiances and territorial claims, as various Maratha chiefs, including the powerful Patwardhans, expanded their domains at the expense of waning Mughal power.

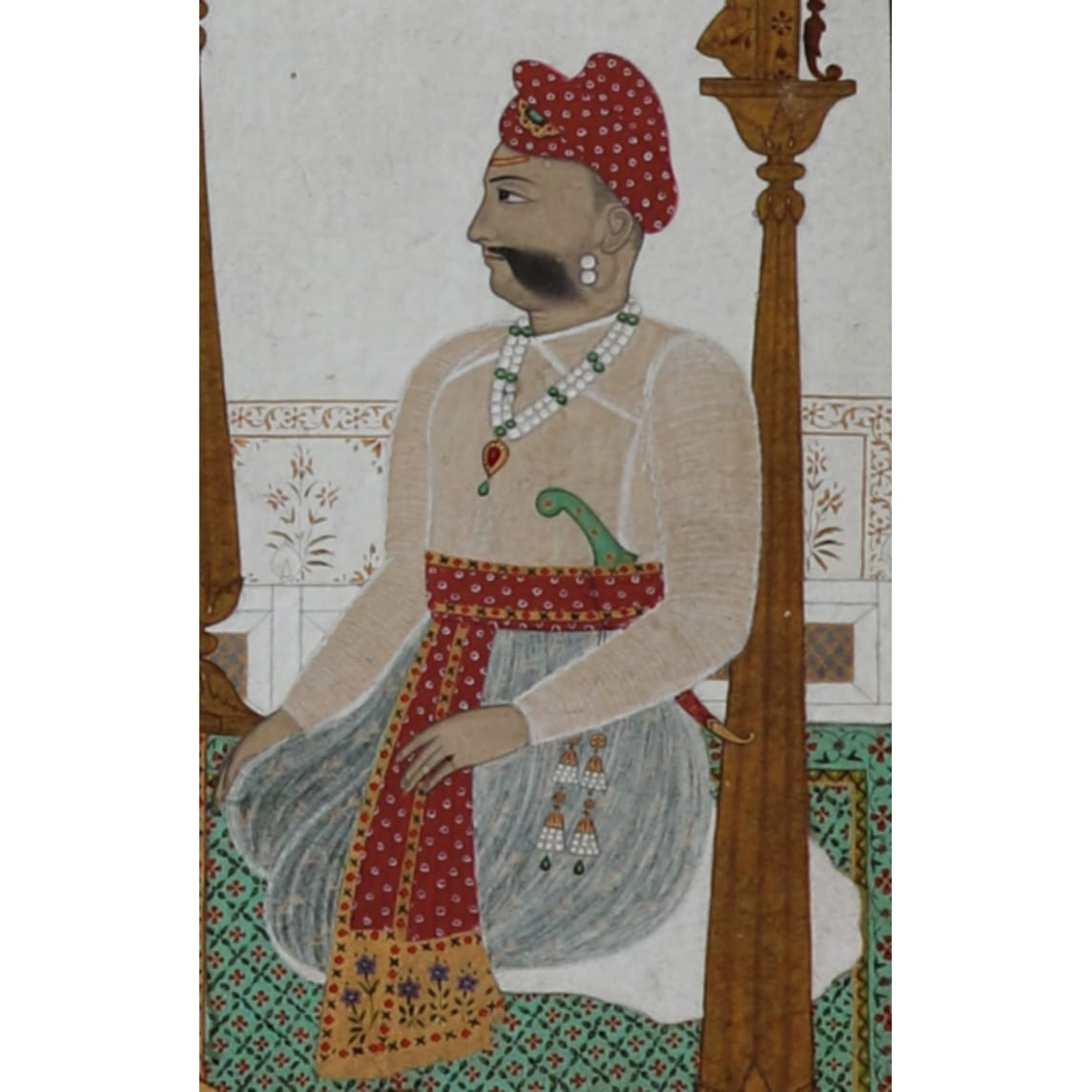

Patwardhans of Sangli

The Patwardhan family, Brahmins of Konkan origin, rose to prominence in the mid-18th century under the patronage of the Peshwas of Pune. Their rise is traditionally traced to Har Bhatt, a family priest associated with the chief of Ichalkaranji (which lies in Kolhapur district). Har Bhatt’s descendants entered the Peshwa’s service through court connections and, over time, came to hold significant military and administrative authority.

A pivotal figure in the family’s ascent was Gopalrao Patwardhan, Har Bhatt’s grandson. His successful campaign against the Nawab of Saoner earned him a jagir at Miraj, as well as control over a local fort. Subsequently, the Patwardhans were granted saranjami lands in 1763, military assignments valued at over 25 lakhs rupees in annual revenue. The location of their headquarters at Miraj was of strategic importance, allowing the family to monitor developments in Kolhapur, Mysore, and beyond.

The Patwardhans remained loyal allies of the Peshwas and played crucial roles in resisting Tipu Sultan and other threats to Maratha dominance. Their influence was such that, by the late 18th century, they had become among the most powerful Maratha nobles in the Deccan, governing large swathes of land through a network of family branches.

Division of Estates & the Founding of the Sangli State

In 1801, internal disputes within the Patwardhan family led to the formal separation of Sangli from the Miraj estate. The schism followed a bitter quarrel between Chintamanrao Pandurangrao Patwardhan, the rightful heir, and his uncle, Gangadharrao Govindrao, who had served as regent during Chintamanrao’s minority.

Chintamanrao had served with distinction in campaigns involving the British, the Nizam of Hyderabad, Tipu Sultan, and Dhondia Wagh. Upon returning from military service, he found his uncle unwilling to cede authority. According to historical accounts, the young chief removed the family murti from the ancestral home in Miraj and established a separate seat of power at Sangli City. From this point, the Sangli State began to function independently, although formal recognition would come later.

The Treaty of Pandharpur (1812) and British Recognition

The rift within the Patwardhan house, unresolved by domestic means, drew the attention of the British authorities, who then acted as arbiters in Maratha affairs. Gangadharrao, through a mixture of courtly influence and intrigue, had by 1808 secured recognition from the Peshwa as the rightful holder of Miraj. Meanwhile, tensions with Chintamanrao continued to simmer.

Continued hostilities between the two branches of the Patwardhan family prompted British intervention. To prevent open conflict, the Resident at the Peshwa’s court brokered the Treaty of Pandharpur in 1812, which formalised the division of territories among the Patwardhan chiefs. The British later recognised the treaty in 1817, and among its clauses was a key provision, as cited in the District Gazetteer (1969), where:

“The strength of the contingents to be supplied for service was considerably reduced, and personal retainers were granted to several members of the family. The terms were gladly accepted by all except Cintamanrao of Sangli, who declined to serve the British Government and was allowed to cede territory of the annual rental of Rs. 1,35,000 in commutation of service.”

The Treaty, later affirmed by the British in 1817, formally recognised the states of Sangli, Miraj, Tasgaon, Sedbal, Kurundwad, and Jamkhandi as distinct political units under Patwardhans. Yet, the spirit of the settlement was soon tested. Chintamanrao, asserting his independence, is said to have issued a formal proclamation to that effect.

With negotiations failing and the situation growing untenable, British forces were dispatched to Sangli. By 1819, realising the futility of resistance, Chintamanrao submitted, and Sangli thereafter became a princely state under British suzerainty.

Colonial Period

During the colonial period, the region corresponding to the present-day Sangli district was not governed as a single administrative unit, but was instead divided among several princely states under British paramountcy. This arrangement took shape following the Third Anglo-Maratha War of 1817–18, which ended with the defeat of the Peshwa and brought Maratha political sovereignty in western India to a close. As part of the post-war settlement, substantial portions of the former Maratha territory were annexed to the Bombay Presidency. Other lands, particularly those granted as military rewards to long-serving commanders, were retained under the new regime as saranjams, or service tenures.

Among the most significant of these were the jagirs held by various branches of the Patwardhan family. Their longstanding military service to the Peshwa state, beginning in the mid-18th century, had earned them widespread holdings across the southern Deccan. These jagirs, however, did not constitute a unified polity. Rather, they were geographically scattered and politically distinct. In the decades following British ascendancy, these holdings underwent a series of formal divisions, each sanctioned by the colonial administration, gradually transforming them into semi-autonomous princely states.

One of the earliest such divisions occurred within the Miraj branch of the Patwardhan family. Shortly after British rule was established, a request was submitted for the partition of their joint saranjam. As this appeal followed prior precedent, it was approved, and the Miraj estate was divided into four parts, of which Miraj Senior and Miraj Junior became the principal states. A similar pattern unfolded in the Jamkhandi line, resulting in the formation of Jamkhandi State and Cinchni (likely corresponding to present-day Chinchani village in Sangli). In 1854, the Kurundvad estate, based in what is now Kolhapur, was similarly partitioned among the heirs of its deceased chief.

To these may be added the Sangli branch, which became the most prominent Patwardhan state in the Deccan, with a direct line of succession from Chintamanrao I “Appa Saheb”, who ruled from 1782 to 1851. The British formally recognised the state's internal autonomy while retaining control over external relations and succession approvals. The Patwardhans of Sangli, as in the other branches, held their territories under the terms of political treaties and maintained their own administrations, revenue systems, and courts.

However, succession remained a sensitive matter, especially in the absence of male heirs. During the early period of British paramountcy, the right to adopt was not presumed; it was treated as a discretionary privilege to be granted by the Government in cases where a ruling chief had demonstrated loyalty or administrative competence. Under this policy, several minor estates in the present-day district were allowed to lapse to British control. These, according to the district Gazetteer (1969) ,were:

- Cinchni (1836)

- Portions of Miraj (1841, 1845)

- Tasgaon (1849)

- Sedbal/Kagvad (1857), both situated in the present-day Kagwad taluk of Belagavi district, Karnataka

In some cases, adoption was initially permitted but later disallowed when the adopted heir died without issue. By the 1850s, dissatisfaction with this restrictive approach was growing among the saranjamdars. While the Patwardhan states themselves remained largely quiet during the events of 1857 (when the First War of Independence took place), the broader unrest across India prompted a rethinking of policy. In the aftermath of the uprising, the Government of India under Lord Canning issued a series of sanads to various princely houses—including the Patwardhans—granting them the general right to adopt. These Canning Sanads curtailed the practice of annexation and restored a measure of dynastic security.

A further development of importance took place in the year 1848, when the British Government revised the terms under which the Patwardhan estates were held. Under the earlier system, the Patwardhan chiefs held their saranjams (territories) on the condition that they would provide military assistance to the ruling power. This obligation dated back to the Maratha period and had continued, in principle, under British paramountcy. However, in 1848, the British government abolished the requirement for active military service and instead converted it into a fixed annual payment. From this point onward, the Patwardhan states were no longer expected to supply troops; they were simply required to pay an agreed sum each year. From that point onward, the Patwardhan rulers no longer had to supply soldiers. Instead, they paid an agreed sum each year, turning their estates into tributary holdings rather than service tenures. The amounts assessed on each of the major Patwardhan states were as follows:

- Rs. 12,558 from Miraj Senior

- Rs. 6,412 from Miraj Junior

- Rs. 9,619 from Kurundvad

- Rs. 20,840 from Jamkhandi

With these changes, the various states within the present-day Sangli district each continued to manage its own internal affairs, including revenue, justice, and public works. By the late 19th century, the states of Sangli, Miraj Senior, Miraj Junior, Jamkhandi, Kurundvad, and Jath came under the supervision of the Southern Maratha Jagirs, later known as the Deccan States Agency. A Political Agent was stationed to oversee external matters, such as succession disputes and treaty obligations, but interference in daily administration was limited.

For the most part, the rulers maintained steady, cooperative ties with the colonial authorities. Their position within the political hierarchy was clear, and their authority in local matters remained largely intact.

The Sangli State and the Rule of Chintamanrao I (1782–1851)

As noted earlier, the Sangli State was among the most prominent of the Patwardhan jagirs in the Deccan region and emerged as a distinct political entity under British recognition in the early 19th century. The earliest and foundational ruler of the Sangli State was Chintamanrao I "Appa Sahib", who formally assumed power in 1782. His rule, however, as noted earlier, was initially guided by the regency of Gangadharrao Govindrao until 1801. His administration coincided with the waning decades of Maratha sovereignty and the early years of British influence. Chintamanrao’s reign extended well into the colonial era, concluding in 1851.

During this time, efforts were made to develop the region’s economic base. The ruler promoted gold mining, sugarcane production, and the local silk and marble industries, laying early groundwork for commercial diversification. To stimulate internal trade, he established several “peth” (market) settlements, which served as commercial and craft hubs. In religious and cultural spheres, In the religious and cultural sphere, his most lasting contribution was the foundation of the Ganapati Panchayatan Sansthan Mandir, which is dedicated to the Patwardhan’s kuldevta (family deity).

Reforms and Joint Administrative during the reign of Dhundirav Chintamanrao (r. 1851–1901)

Chintamanrao I was succeeded in 1851 by his son, Dhundirav Chintamanrao “Tatya Saheb,” who was a minor at the time. The state remained under regency until 1860. During his long rule, efforts were directed toward institutional development, particularly in the fields of education and public health. A municipal body was constituted for Sangli, and one of the earliest public libraries in the region was established. A hospital was opened in 1855. Schools offering instruction in English and Sanskrit were founded, and notably, free education was extended to socially disadvantaged groups.

By the latter part of his rule, however, administrative concerns attracted the attention of the British authorities. In 1873, Captain West was appointed joint administrator of the Sangli State. Dhundirav is noted to have refused to cooperate with the appointed officer, remaining aloof from the day-to-day functioning of the joint administration. In 1878, Major Waller assumed charge of the joint administration, which continued until 1880, when the Raja was formally restored to full powers on his undertaking to exercise better oversight. Nonetheless, supervision by the Political Agent remained in place for some time thereafter.

Regency and Administration under Chintamanrao Dhundirav Patwardhan (r. 1901–1947)

Following the death of Dhundirav Chintamanrao in December 1901, the succession passed to his adopted son, Chintamanrao Dhundirav Patwardhan, who was then a minor. During the period of minority rule, the administration of the State was conducted under the supervision of officers appointed by the British Government. From 1901 to 1905, affairs were managed by A. B. Desai, followed by Captain Richard John Charles Burke, who held charge until 1910. In June of that year, Chintamanrao attained majority and assumed full powers of rule.

The period of his administration, extending until the end of British paramountcy in 1947, was marked by several institutional developments. In the field of education, the establishment of Willingdon College provided a centre of higher learning which served not only Sangli but the broader region of southern Maharashtra. Financial consolidation was also undertaken, and in 1916, the Sangli Bank Ltd. was founded to provide structured banking services to the local economy.

Chintamanrao was granted the title of “Sir” on 1 January 1923, in recognition of his status and services. He remained in office until the dissolution of paramountcy in August 1947, following which the State acceded to the Indian Union by signing the Instrument of Accession. Sangli was merged with the Bombay State in 1948. Thereafter, the Patwardhan family retained ceremonial standing but no longer exercised sovereign authority.

All together, the following is a chronological list of the rulers of Sangli State, including periods of regency where applicable.

- Chintamanrao I “Appa Saheb” (r. 1782–1851) – Regency: Gangadharrao Govindrao (1782–1801)

- Dhundirav Chintamanrao “Tatya Saheb” (r. 1851–1901) – Regency during his minority (1851–1860)

- Sir Chintamanrao Dhundirav Patwardhan “Appa Saheb” (r. 1901–1932) – Regency during his minority (1901–1910), according to the district Gazetteer (1969), was held by A. B. Desai (1901–1905) and Captain R. J. C. Burke (1905–1910)

- Raja Chintamanrao Dhundirav Patwardhan (r. 1932–1965)

- Raja Vijaysinh Patwardhan (1965–present; ceremonial head)

Jath and Daphlapur under British Rule

Alongside the Patwardhans, the Daphale family (briefly mentioned above), who were the hereditary Deshmukhs of Jath, also governed a large jagir in the parts of present-day Sangli district during this period. The town of Jath (in Sangli district) served as the administrative headquarters of the estate throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Notably, during this period, and in contrast to the neighbouring Patwardhan states (where succession generally proceeded along more continuous lines), the Jath State witnessed a series of succession changes which frequently involved widow administrators and the adoption of heirs in the absence of direct male issue. These transitions, while not uncommon for the period, brought the estate into regular correspondence with the British authorities overseeing the Southern Maratha States. It is also of note that a greater degree of matrilineal authority, through female regents or widows in charge, can be observed in Jath during this period than in many neighbouring estates.

Following the fall of the Peshwas in 1818, the British recognised Renukabai, widow of the deceased chief Khanajirao, as head of the estate. Her administration continued until she died in 1823, after which her co-widow, Salubai, held power for ten months. After her death, the jagir was then temporarily taken under the authority of the Raja of Satara, but was restored shortly thereafter to a male member of the family, Ramrao Daphale.

Ramrao died in 1835 without leaving an heir. In 1841, with the sanction of the British Government, his widow, Bhagirathibai, adopted Bhimrao, who later assumed the name Amritrao II. During his minority, the estate was managed by his adoptive mother and later under British supervision. Amritrao came of age in 1855, but friction soon developed between the State and the British political officers. During the Revolt of Shorapur in 1857–58, British officials suspected Jath of maintaining communication with its Raja. Although no uprising occurred within the Jath estate itself, the state’s arms were confiscated, and surveillance was increased.

By the early 1870s, continued complaints of misrule prompted further intervention. According to the district Gazetteer (1969), in 1872, following an official inquiry conducted by Captain West, the British Government withdrew civil and criminal powers from Amritrao. Authority was transferred to a karbhari (a government-appointed manager), who held magisterial and judicial powers and reported to the Political Agent. This administrative arrangement remained in effect for the rest of the colonial period. The Daphale chief retained ceremonial status and continued to pay tribute of Rs. 4,739 instead of sardeshmukhi rights and Rs. 6,400 in place of military service, but exercised no direct authority thereafter.

A smaller estate associated with the same ruling house was Daphlapur, located to the west of Jath and administered independently by a cadet branch of the Daphale family. It consisted of six villages and appears to have remained politically distinct throughout the colonial period. In the late 19th century, it was governed by Baisaheb Lakshmibai Daphale, whose position was formally recognised by the Government. She retained judicial and magisterial authority and appears to have exercised effective administrative control during her tenure.

Kirloskarwadi and Industrial Enterprise

Alongside political change, the early 20th century saw steady industrial growth in the Sangli region. Among the most significant of these developments was the establishment of the Kirloskar Industrial Works in 1910 by Laxmanrao Kirloskar, an engineer and entrepreneur formerly based in Belgaum (which lies in Karnataka). The factory was located at Kundal Road, a station on the Southern Mahratta Railway, chosen for its proximity to agricultural zones in the Krishna River valley and its access to rail transport.

The enterprise, later named Kirloskar Brothers Ltd, initially specialised in the manufacture of iron ploughs and mechanical pumps, products aimed at the region’s agrarian market. Over time, the works expanded to include foundries, machine shops, and residential quarters, forming the nucleus of what came to be known as Kirloskarwadi. By the 1930s, the site had developed into a functioning industrial township, distinct from the surrounding rural settlements. The factory provided regular employment and became a centre for mechanical supply in the southern Bombay Presidency. It is now considered India’s second-oldest industrial township.

During the 1940s, Kirloskarwadi gained attention for its association with the national movement. The township offered shelter to underground workers, and several employees participated in strike actions and satyagraha campaigns. A memorial was later erected in honour of those involved.

Artisanal Production of Musical Instruments in Miraj

Another notable development during this period came with the rise of Miraj as a centre for the manufacture of Indian string instruments, particularly the sitar and tanpura. The craft became associated with the Shikalgars, a community of metalsmiths who had formerly been employed in the repair of arms and armour under the Bijapur Sultanate. With the decline of military demand and the standardisation of British arms, members of the community gradually turned to other branches of artisanal production.

The shift toward instrument-making occurred in the late 19th century, largely owing to the efforts of Faridsaheb Sitarmaker, who was a member of this community (refer to Artforms for more). His work gained recognition across India, and Miraj gradually drew visiting musicians who came both to perform and to commission repairs and new instruments.

The craft received continued encouragement from the ruling house of Miraj Senior, notably under Shrimant Balasaheb Patwardhan II (r. 1866–1939), who is recorded as having taken an active interest in classical music. Through his patronage, the town came to be associated with the Kirana Gharana, and the manufacture of instruments developed into a hereditary occupation. A dedicated quarter of workshops, known as Sitarmaker Galli, took shape within the town and continues in operation. Today, the craft remains one of the more distinctive artisanal traditions of the district, and is now recognised under the Geographical Indications (GI) registry.

Peasant Movement in Miraj

In the early decades of the 20th century, the Miraj State also witnessed growing rural unrest, largely in response to repeated seasons of agricultural distress and the continued enforcement of land revenue demands. Despite the prevailing conditions, the state authorities are said to have maintained existing assessments and introduced further increases in some areas, contributing to widespread dissatisfaction among cultivators.

During this period, political organisation within the princely states began to take form under the Praja Parishad, a regional platform distinct from the Indian National Congress but broadly aligned in its calls for administrative reform. In Miraj, between 1922 and 1928, notably, four sessions of the Parishad were held. These meetings raised demands for revenue relief, improved governance, and an end to what were described as coercive methods of collection. Estimates suggest that as many as 4,000 peasants participated in satyagraha-related actions. A formal resolution was adopted during the fifth session, followed by a petition submitted to the authorities at the sixth.

Political activity intensified with the launch of the Civil Disobedience Movement in 1930. In response, the Miraj administration imposed restrictions on public gatherings and proscribed political assemblies. Undeterred, sections of the rural population initiated a No-Tax Campaign, which soon drew national attention.

This momentum continued into the late 1930s. In 1938, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel addressed a session of the Dakshini Sansthan Lok Parishad convened in the present-day district. A resolution was passed seeking land revenue concessions. Shortly thereafter, the state announced a 20 per cent remission in assessments, and restrictions on assemblies were formally lifted.

Political Developments in Sangli State

Parallel to the events in Miraj, political mobilisation was also taking shape in Sangli State. In 1922, the Sangli Praja Parishad was established as a local representative body. Through it, cultivators and townspeople expressed concerns over revenue policy, administrative oversight, and the absence of any representative mechanism within the state structure. Early resolutions of the Parishad addressed the growing economic pressures on the rural population and called for institutional reform.

Though unaffiliated with any national party, the Parishad often aligned itself with the broader aims of the Indian National Congress and received intermittent support from its members. The body remained active through the 1920s and 1930s, petitioning the state for relief and improved governance.

The Civil Disobedience Movement of 1930 led to renewed mobilisation within the state. In response, the administration imposed restrictions on political meetings and public assemblies. Despite this, the Parishad continued to organise and remained a point of contact between the population and the state.

The Jungle Satyagraha in Kavathe

While political activity was advancing in the administrative centres, agitation also emerged in the agrarian tracts of the district. Here, resistance took a different form and was directed against forest regulations introduced under the British-imposed Forest Act, which restricted grazing rights and auctioned off grasslands traditionally used by cultivators.

In late 1930, one such protest took place in Kavathe village, where residents entered reserved forest land in defiance of state authority. The movement was led by Kisan Veer, who was arrested and sentenced to eleven months' imprisonment. Upon his release, the agitation spread, drawing wider support across the district. Those involved faced lathi charges, arrests, and physical reprisals.

Among those who took part in the Kavathe Jungle Satyagraha were Kisan Veer, Shridhar Kulkarni, and Babu Satpute, all of whom were detained or otherwise penalised for their participation.

The Armed Resistance of Veera Sindhura Lakshmana

Armed resistance was also recorded during this period, particularly in the border regions of Sangli. One such instance involved a local figure named Sindhura Lakshmana, who was a resident of the village of Sindhur in present-day Jath taluka.

Between 1920 and 1922, Lakshmana and a group of associates conducted raids on colonial treasuries and government posts. The proceeds from these raids were, according to local accounts, distributed among the rural population. Lakshmana’s activities were treated as criminal by colonial authorities, and he was eventually killed in 1922 during a covert operation carried out by police personnel. The episode today stands as one of the lesser-known instances of individual resistance in the region.

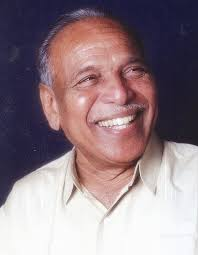

Nagnath Naikwadi and the Prati Sarkar

Another figure from Sangli district known for his role in organised resistance during the later phase of British rule was Nagnath Naikwadi of Walwa village. Born in 1922, Naikwadi became politically active in the early 1940s through his involvement with the Rashtra Seva Dal and later aligned closely with Nana Patil, a key organiser of underground resistance in western Maharashtra. His activities were centred largely in Satara and Sangli and contributed directly to the formation and functioning of the Prati Sarkar (parallel government).

During his early years, Naikwadi participated in the looting of a colonial treasury in Dhule to raise funds for resistance activities. He was also involved in operations against the Hyderabad State. During one such action, he was injured and captured by colonial police, and subsequently held at Satara jail. He later escaped from custody. Declared a wanted man, he evaded arrest and remained in hiding for several years.

In 1943, Naikwadi played a leading role in the establishment of the Prati Sarkar, a parallel administrative structure which operated in approximately 150 villages across the present-day Satara and Sangli districts. The organisation conducted village-level governance independent of British authority, handling tasks such as local dispute resolution, grain distribution, and the protection of underground activists. In the present-day Sangli district in particular, Naikwadi likely emerged as a principal coordinator of these efforts.

The Prati Sarkar remained active between 1942 and 1946, forming part of a broader pattern of rural mobilisation and anti-colonial activity in western Maharashtra during the Quit India movement. Within this framework, Sangli served as one of the key centres of resistance, and Naikwadi’s contributions placed him at the core of its local organisation.

Women’s Participation in the Freedom Movement

The later years of the freedom movement also saw women in Sangli district becoming increasingly active in the national struggle. From the early 1920s through to the Quit India Movement, they played both direct and supporting roles in political agitation. A key moment came with Mahatma Gandhi’s visit to Sangli on 12 November 1920. His presence prompted widespread public engagement and is said to have marked a notable rise in women’s political involvement in the region.

Several of these women were linked with the Prati Sarkar movement led by Nana Patil, particularly in the years between 1942 and 1946, when portions of the present-day district saw the rise of parallel administrations and a surge in underground resistance.

Notable among those involved were Leelatai Patil, Rajmati Patil, Hausabai Chaugule, Indutai Patankar, Lakshmibai Naikwadi, and Kalantreya, whose efforts extended across Sangli and neighbouring districts and contributed significantly to the functioning of local resistance networks.

Post-Independence

In 1947, upon the attainment of independence, the princely states of Sangli were merged into the Indian Union and their political and social structures were gradually integrated into the administrative framework of the Indian Republic. Upon accession, Sangli was incorporated into the Bombay State, a large administrative unit that, at the time, included much of present-day Maharashtra and Gujarat.

On 1 August 1949, the region was formally constituted as a district, originally under the designation South Satara. This designation continued until 21 November 1960, when the district was renamed Sangli, aligning with administrative and linguistic realignments taking place across the country.

The most significant of these realignments came with the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which redrew internal boundaries based on language. Although Sangli remained part of Bombay State following the reorganisation, continued agitation for a distinct state for Marathi-speaking regions ultimately led to the division of Bombay State. On 1 May 1960, two new states were created: Maharashtra, for Marathi speakers, and Gujarat, for Gujarati speakers. With this, Sangli was incorporated into the newly formed State of Maharashtra.

Turmeric Production and Its Commercial Expansion

In the decades following independence, Sangli district emerged as one of the most prominent turmeric-producing regions in the country. The southern talukas of the district- Miraj, Tasgaon, Palus, Kadegaon, Walwa, Vita, Khanapur, and Chinchali- proved especially well-suited to turmeric cultivation, owing to their black cotton soil and semi-arid climate.

The turmeric of Walwa and Miraj in particular came to be noted for its high sugar content, distinctive deep saffron colour, and a specific root structure, known locally as halakunda, that was easy to break and thus prized in trade. In 2018, Sangli turmeric was granted a Geographical Indication (GI) tag based on these characteristics. Over time, this association with turmeric has led to the district being referred to, informally, as the ‘Saffron City’ of the Deccan.

It is interesting to note that historically, large quantities were exported through the Rajapur harbour (in Ratnagiri), and the product became known as Rajapuri turmeric. In 1910, an auction system was introduced in Sangli, contributing to the organised trade and international recognition of its turmeric.

Sources

B. N. Sardesai. 1993. "The Peoples' Awakening in Sangli State." Vol. 54,Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44142997?seq=1

Deepak Bhau Kumbhar. n.d. String Masters: Sitarmakers of Miraj. Sahapedia.https://www.sahapedia.org/string-masters-sit…

Indian Culture. n.d. Jungle Satyagrah at Kavathe. Indian Culture Digital Repository.https://indianculture.gov.in/digital-distric…

Indian Culture. n.d. Peasant Movement in Miraj. Indian Culture Digital Repository. https://indianculture.gov.in/digital-distric…

Mayuri Phadnis. 2016. Six new ancient Buddhist caves found in Sangli. Pune Mirror.https://punemirror.com/news/six-new-ancient-…

Shyam Prasad. 2019. Kannada inscription from 11th CE in Sangli. Bangalore Mirror, India Times.https://bangaloremirror.indiatimes.com/news/…

The Week. 2024. Sitars, Tanpuras Made in Maharashtra’s Miraj Town Get GI Tags. The Week, India. https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2024/04/07…

Viraj Shah. 2009. A study of temples of medieval Maharashtra (11th to 14th centuries CE). A socio-economic approach. Report submitted to Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), New Delhi, for Post-Doctoral Fellowship.https://www.academia.edu/41462964/A_STUDY_OF…

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.