Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Vasota Fort

- Jabareshwar Mandir

- Buddhism

- Karad

- Karad Caves

- Shirval Caves

- Trading Passes

- Pandavgadh

- Kenjalgadh

- Vandhan Fort

- Mahabaleshwar

- Mahabaleshwar Mandir

- Bhushangadh

- Medieval Period

- Bahmani Sultanate

- Sajjangadh

- Durga Devi Famine, 1396 to 1407

- Bahmani to Bijapuri Sultanate

- Land Reform

- Samarth Ramdas

- Rise of Shivaji

- Local Rajas of Satara

- Ravaji Nimbalkar of Phaltan

- Mores of Javali

- Fall of Jawali

- Pratapgadh

- Battle of Pratapgadh

- The Meeting with Afzal Khan

- Bhavani Mandir

- Ajinkyatara Fort

- Kamalgadh

- Under Sambhaji I and Rajaram I

- The Aundh State

- Chhatrapatis of Satara

- Shahu I, 1707–1749

- Rajaram II, 1749–1777

- Pratapsingh, 1808–1839

- Rajwadas of Satara

- Juna Rajwada

- Nava Rajwada

- Krishna-Venna Sangam

- Vishveshwar Mandir

- Rameshwar Mandir

- Memorial of Maharani Yesubai

- Phaltan Rajwada

- Shri Ram Mandir

- Colonial Period

- Formation of Satara District, 1848

- Mahabaleshwar: Summer Capital of Bombay Presidency

- “First War of Independence”, 1857

- Local Administration

- Revenue Administration

- Mirasi Tenure (Hereditary Landholding)

- Categories of Mirasdars

- Upri (Casual Tenure)

- Sheri (Crown Lands)

- Forms of Tenure

- Prison for Chinese and Malaya convicts

- Education Hub

- Panchgani Boarding Schools

- Sanatorium

- Mahabaleshwar Strawberries

- Sugarcane Industry

- Other Industries

- Civil Disobedience Movement

- Aundh Experiment

- Prati Sarkar or Parallel Government in Satara

- Post-Independence

- Kaas Pathar

- Sources

SATARA

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Satara district, located at the foothills of the Western Ghats, sprawls across the inland Deccan Plateau. Surrounded by majestic hills, this district has long been revered for its strategic importance, drawing the attention of various ruling powers who desired control over its lands. The district gained its utmost political significance when Chhatrapti Shahu I made Satara his capital.

The narrative of Satara district's history stretches back to ancient times. According to local belief, it was in the district that Bhagwan Ram resided on his way to exile, adding cultural significance to the region. Over the centuries, the district witnessed the rise and fall of different dynasties, with the Adil Shahis reigning over the district before being succeeded by the Marathas. The remnants of Islamic rule still manifest in the district’s architecture and heritage today. For the Marathas, Satara held great significance, leading to the construction of numerous forts that bear witness to the district's political significance as well as its turbulent past. Many significant battles were fought on the hallowed grounds of the district, shaping the course of history.

During the colonial era, the British were drawn to Satara's allure, transforming it into a hill station reminiscent of their English landscape. However, despite attempts at emulation, Satara retained its distinct identity and resilience. Throughout the struggle for independence, the district remained steadfast, with its inhabitants making significant contributions to the cause. Their unwavering spirit and determination served as a testament to the district's enduring legacy of resistance and resilience.

Etymology

The name "Satara" is commonly believed to come from the Marathi words Sat-Tara, meaning "seven stars," a reference to the seven hill forts traditionally thought to encircle the district. Another theory suggests the name evolved from "Satare," linked to seven prominent hills guarding the city—though some argue there are actually nine. Among these hills stands the sacred Saptarshi Mandir, dedicated to the seven celestial sages of Hindu lore. Ancient texts like the Puranas even refer to the area as "Saptarshipur," reflecting its mystical association with the heavens.

Ancient Period

Although specific historical records may be limited for certain periods, it is evident that various dynasties and rulers shaped the history of Satara. The Andhrabhartyas or Satavahanas ruled the district from 90 BCE to 300 CE. Their rule was characterised by the proliferation of Buddhism in the district. According to the district Gazetteer (1885), the district must have been under the Kolhapur branch of the Satavahanas, who held sway over Satara.

From 550-760 CE, the Western Chalukyas emerged as a dominant power in the region, marking a significant period of political influence in the district. It is probable that they returned to prominence, asserting their authority over Satara once again from 973 to 1180 CE. Continuing the region’s political dynamics, the Rashtrakutas rose to power and ruled over Satara between 760-973 CE.

From 1050-1220 CE, the Kolhapur Silaharas, a local dynasty, held sway. They are known to have brought stability and cultural development to the region. During the reign of Jatiga-II, Karad was initially their capital. This information is derived from the copper plate grant of Miraj and the Vikramankadevacharita of Bilhana. In fact, they are sometimes referred to as the 'Shilaharas of Karad.' However, the capital was later relocated to Kolhapur.

Among the Silaharas of Kolhapur who held sway over Satara and Belganv districts from 1000 to 1215 CE, Raja Gonka is particularly noteworthy. He is described as the raja of Karhad (Karad), Mairifvja (Miraj), and the Konkan region. The legacy of the Kolhapur Silharas is evident in the numerous forts they constructed, showcasing their existence and their architectural prowess. These forts were further fortified by subsequent powers and repurposed for defence, highlighting their strategic significance in the region.

Following the Silharas, the Yadavas of Devagiri gained control of Satara, further shaping its political landscape during this period before the advent of the Delhi Sultanate in the district.

Vasota Fort

Vasota Fort, also known as Vyaghragad, is located near Bamnoli village within the Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary in Satara district. Surrounded by dense forests and steep cliffs, it holds both historical and cultural significance. According to the Satara District Gazetteer (1963), the fort is attributed to the Shilahara ruler Bhoja II (1178–1193) of Kolhapur. It later came under the control of the Shirkes and Mores before being captured by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in 1655 after his conquest of Javli, at which point he named it Vyaghragad.

The fort is also remembered for the story of Tai Telin, who is said to have defended Vasota for eight months against the Peshwa’s forces in 1806, during the imprisonment of her husband, Pant Pratinidhi, by Bajirao I. Eventually, the fort was taken by the British, likely during the Third Anglo-Maratha War.

During Shivaji Maharaj’s campaigns, Vasota served as a strategic base for resisting the Mughal forces. Its remote location in the forests of the Sahyadris provided natural defense and helped in launching surprise attacks. Apart from its historical importance, Vasota Fort is admired for its scenic surroundings within the Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary. The route to the fort passes through rich forests and varied landscapes, making it a popular trekking destination. Remains of bastions, water tanks, and small mandirs can still be seen, offering insight into Maratha fort architecture.

Locally, the fort is also linked to legends from the Ramayan, with some traditions believing that Bhagwan Ram stayed here during his exile. This association adds to the cultural significance of the site. Today, Vasota Fort attracts trekkers, nature enthusiasts, and history lovers who visit for both its breathtaking views and its connection to the region’s past.

Jabareshwar Mandir

Jabareshwar Mandir is a rock-cut structure located in Phaltan town in Satara district. Believed to have been carved from a single rock around 1237 CE, the Mandir is an example of Hemadpanti architecture and is thought to have been originally dedicated to the 23rd Jain Tirthankar. Over the centuries, the structure has witnessed several transitions, with a Shivling now installed inside its garbhagriha (sanctum).

Though the Mandir is a protected monument under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, its history remains largely undocumented. The Mandir’s external carvings depict human figures in expressive poses, while the interiors—cool and shaded—feature colourful walls and images of various deities. A Nandi murti faces the Shivling, and the Mandir is unusual in that the Shivling is placed east to west, with the entrance facing north, differing from most other Shiv mandirs in Maharashtra.

Located amidst the busy market lanes of Phaltan, the Mandir is surrounded by shops and rarely visited, except by occasional travelers. Though largely unknown to tourists today, it remains a significant but overlooked example of medieval rock-cut architecture in the region.

Buddhism

Buddhism had a significant influence in the district, going as far back as the 3rd century BCE. This was during the time when the Satavahanas ruled a majority of Maharashtra. The inscriptions found at the Bharhut Stupa, dating back to about 200 BCE., indicate the presence of Buddhist pilgrims and activity in the area during ancient times. According to the Gazetteer(1885), the presence of three inscriptions dating back to about 200 BCE., document the donation of pillars by Karad pilgrims at the Bharhut Stupa (presently in Jabalpur in the Central Provinces). It indicates that Karad, or as referred to in the inscriptions, Karahakada, located approximately fifteen miles southeast of Satara, is likely one of the oldest sites in the district.

Karad

Originally known as Karhatak, this town is believed to have gotten its name from a term that means "Elephant Market." Karad in the district finds mention in ancient texts such as the Mahabharat, suggesting that it has a significant cultural and historical legacy. The town is mentioned in relation to Sahadeva, one of the Pandavas who resided there. These references indicate that the town has been a centre of human settlement and cultural activity since ancient times, contributing to its status as a city of historical importance.

It is of immense cultural significance to the locals as Karad is situated at the confluence of the Koyna River and the Krishna River, a location known as Pritisangam. These two rivers originate from Mahabaleshwar, which is situated approximately 100 kilometres away from the town in the district. Moreover, several ancient Buddhist sites are located in the town, enhancing its significance as a Buddhist cultural centre.

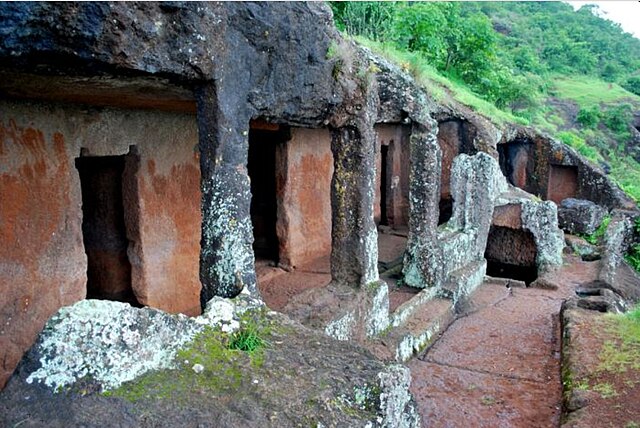

Karad Caves

According to the Gazetteer(1885), Karad is home to a cluster of 63 early Buddhist caves. The gazetteer mentions that these caves are situated approximately three miles southwest of Karad. Interestingly, one of these caves bears an inscription from around the 1st century CE. These caves add immensely to the significance of the district as an ancient buddhist site and spread of Buddhism in the region.

The number of caves at present, however, is 66. Nestled around Agashiv hill, they are situated approximately five kilometres southwest of Karad. This is near the village of Jakhinwadi, overlooking the Koyna River. It is believed that the caves facing south hold particular significance. Additionally, some caves are also found in the valley. Notably, one of the caves is named after Chokhamela, who resided there for about 8 years.

The Karad Caves are a group of ancient Buddhist rock-cut caves located about 5 km southwest of Karad, near the village of Jakhinwadi in Satara district. Overlooking the Koyna River, these caves are carved into the Agashiv hill and its surrounding spurs. Together, they form one of the earliest and largest groups of Buddhist caves in Maharashtra, with a total of 66 excavations spread across three main clusters—Agashiv Caves, Bhairav Caves, and Dongrai Caves.

Dating back to the 1st century BCE, the caves are noted for their simplicity, with plain viharas (monastic dwellings) and small chaityas (prayer halls). They are among the earliest examples of rock-cut Buddhist architecture in the region, roughly contemporary with sites like Karle, Bhaja, and Nasik. Many caves contain stone benches carved for use as beds. Some caves retain carvings of Buddhist symbols such as wheels (chakras) and lions (simhas), especially seen in Cave 5 and Cave 30. A significant inscription in the caves records a donation by Sanghamitra, the son of Gopala, highlighting the site's early religious patronage.

One of the caves is also traditionally associated with Chokhamela, the 14th-century Varkari sant, who is believed to have stayed there for several years.

Though mostly plain, the caves offer glimpses of early Buddhist architectural styles. Features like square window openings, stone relic shrines (daghobas), and faint traces of early sculptures connect them to the early phases of Buddhist cave development in western India. The soft amygdaloidal rock in which the caves are carved has suffered significant weathering, with only a few inscriptions and reliefs remaining legible today.

The Karad Caves hold archaeological importance not only for their early date but also for their role in tracing the spread of Buddhism in Maharashtra. Their association with both ancient Buddhist traditions and later Bhakti figures like Chokhamela makes them a unique site linking different spiritual movements in the region.

Shirval Caves

According to the Gazetteer (1885), additional evidence of ancient Buddhist settlements are found in caves located at Shirval. This is in the extreme northwest, at the sacred town of Wai in Jivli (present Jawali village). The Shirwal Caves comprise a collection of 15 Buddhist caves situated in the quaint village of Shriwal, located 48 kilometres south of Pune.

Among these caves, one serves as a Chaitya, or prayer hall, while the remaining 14 caves function as Viharas, or residential cells for monks. All of these caves are characterised by their simplistic design and architecture, indicative of the early phase of Buddhism.

Trading Passes

The district is likely had a reputation for its commercial activities. The famous Varandha and Kumbharli passes were connected with the Konkan seaports such as Mahad, Dabhol, and Chiplun (see Ratnagiri for more). According to the Gazetteer (1885), these passes, cutting across the western ghats, likely connected inland areas with coastal trading centres, contributing to the economic activity in the district. Additionally, the mention of early Buddhist settlements and pilgrimage sites in the district indicates that it may have been a hub for travellers, traders, and pilgrims who traversed through this trading passes for various reasons, further enhancing its commercial significance.

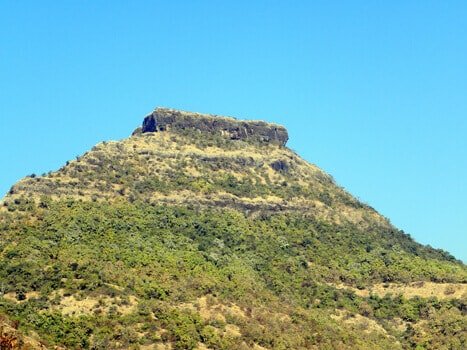

Pandavgadh

Pandavgadh, also known as Pandugadh, is another historic fort. It is situated four miles north-west of Wai and is 4177 feet above sea level. The fort is believed to have been built by the Kolhapur Silahara Raja Bhoja II (1178-1193) of Panhala. Although there is no conclusive evidence, it is probable that the fort is named after the Pandavas. Given that the Pandavas are believed to have traversed this district on their journey to exile, it's plausible that they paused in this area. This historical connection likely inspired the Silhara rulers to name the fort after the Pandavas. The fort offers a very good view of the surroundings and is located strategically atop a hill.

In the 17th century, the fort was under the charge of a Bijapur mokasdar (official) stationed at Wai. In 1673, it was taken by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. In 1713, Balaji Vishvanath, the first Peshwa, sought shelter at the fort during his flight from Chandrasen Jadhav, the Maratha Senapati. It was surrendered to Aurangzeb's officers during the late 19th century.

The fort is in close proximity to Mahabaleshwar and is surrounded by caves, including a flat-roofed chaitya, an eight-celled vihar (dwelling cave), and a daghoba (relic shrine). The fort is largely spread over six acres and has a mandir in memory of Vaman Pandit, the famous Sanskrit poet of the 15th century.

Kenjalgadh

Kenjalgadh, also known as Ghera Khelanja Fort, is a hill fort located in the district. It is situated on the Mandhardev spur of the Mahadev hill range, approximately 18 km north-west of Wai. The fort is visible from a distance due to its stone scarp that is 30-40 feet high, rising as a cap on the irregular hill. Kenjalgad Fort is rhomboid in shape with a long axis of 388m and a short axis of 175m. The fort is believed to have been built by Kolhapur Silhara Raja Bhoja II of Panhala (present city in Kolhapur) in the 12th century.

The fort has its own share of changes, with many different rulers acquiring it. In 1648, it was annexed by the Adilshah of Bijapur. However, in 1674, it was captured by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj during a military campaign at Chiplun (present city in Ratnagiri district). The fort was then captured by Aurangzeb in 1701. Finally, in the aftermath of the 3rd Anglo-Maratha War, it was captured by the British in 1818. It is believed that there were three large and six small water tanks on the fort, but they were drained out by the British after capturing the fort.

The fort is accessible by road from Wai (25 km) or Bhor (17 km). It is a small plateau with a ruined main entrance and a small magazine room without a roof. It is said that there are pratima of Kenjai Devi on the fort, and two lime mixers with mortar stones are in good condition.

Vandhan Fort

Vandhan Fort is one of the twin forts of the district, the other being the Chandan Fort. It is situated near Bhunj, approximately 110 kilometres from Pune. It is believed that stone pillars at the fort entrance have remained undisturbed for several centuries, despite the destruction of most monuments and cannons on the fort during the Anglo-Martha conflict. It is believed that the fort is a part of the Silhara’s legacy and perhaps built by King Bhoj-II in 1191-1192. The forts likely came under Maratha rule in 1673, when Shivaji Maharaj captured them before his coronation ceremony.

Following this, Mughals were dominant in the region. Emperor Aurangzeb took control of the forts in 1701, but Chhatrapati Shahu regained control in 1707, marking the last battle fought on these forts. During the Peshwa regime, the forts were used as a watchtower and a prison.

Mahabaleshwar

Mahabaleshwar, a scenic hill station in the Western Ghats has a rich and deep history that dates back centuries. Its history is a fascinating blend of ancient mandirs, historical sites, colonial architecture, and modern developments. While these hills were originally inhabited by local tribal communities, there is limited documentation available to trace their history in the region. According to the Gazetteer (1885), the locals of the region includes the Kolis, Kulvadis or Kunbis, Dhangars, and Dhavads communities.

The history of Mahabaleshwar can be traced back to the 11th century, when a Yadava King of Devgiri constructed a small mandir in the area. It is of utmost religious significance to the locals as the river Krishna has its origin here. However, the place did not gain popularity until the 1350s, when the Satara king began ruling the area and granted peace and growth to the place.

It is believed that the region surrounding Mahabaleshwar, known as the Vale of Jawali, was governed by the More clan. They served as vassals to the Adil shahi sultanate of Bijapur and ruled Mahabaleshwar during the time. In 1656, due to prevailing political conditions, Chhatrapati Shivaji, took action against Yashwantrao More and annexed the territory.

Mahabaleshwar Mandir

One of the most famous mandirs in the town is the Mahabaleshwar Mandir, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv. It adds to the cultural significance of the district. According to legend, the entire hill station of Mahabaleshwar was created by Bhagwan Shiv, who struck the earth with his trishul and created a spring that became the source of the Krishna River. The mandir is a popular pilgrimage site for Hindus and attracts many devotees throughout the year.

Bhushangadh

Bhushangad Fort is another significant fort in the long list of historical forts in the district. It is located in the present Khatav taluka in the district. It was originally built by Singhan II of the Yadava Dynasty of Devagiri around 1210-1247. Bhushangad Fort is located about eleven miles south-west of Vaduj in the Satara region of Pune. The fort is roughly oval in shape and has a solitary hill that rises above the surrounding plain. The north-west half of the slope has several houses that were mostly inhabited by Brahmans who were attached to the fort garrison. The fort has a mandir of Harinai Devi, which is a form of Durga Devi, and a mandir devoted to Hanumanji, also known as Maruti.

Although the origin of the fort was attributed to Yadavas, the fort was repaired by Shivaji about 1676, and it sustained an attack from Fattesingh Mane in 1805. The fort was under the control of the Marathas, but it was later conquered by Aurangzeb and believed to have been renamed "Islamtara".

During the rule of the Peshwa, the fort was under the control of the Pant Pratinidhi. Currently, the fort is roughly triangular in shape and has observation bastions at all three ends. The ramparts of the fort are still in good condition, and bastions have been built at various places in the ramparts. The ramparts have a total of ten bastions, including the two bastions at the gate. The fort is a testament to the architectural prowess of the Marathas and offers a glimpse into the rich history of the region.

Medieval Period

Bahmani Sultanate

The district came under Muslim rule after the Yadava line was extinguished in 1317-18. Soon after, the district became a part of the Bahamani sultanate. In 1357, Alauddin Bahman Shah, the founder of the Sultanate, reorganised the administrative structure of his kingdom. He divided his kingdom into four taraf (provinces), appointing a provincial tarafdar (governor) over each. A large part of the district stretched into the Kulbarga province (in present Karnataka), with its territories going as far as Raichur and Mudgal in the south (both in present Karnataka). In the west, it stretched from Kulbarga to Dabhol (in the present Ratnagiri district). Alauddin's control over the district encompassed the entire region, except for the hilly west, which remained independent along with the Konkan until about a century later. According to the Gazetteer (1885), it was around this time (1358-1375) that the fort of Satara, along with many others, was likely constructed.

Sajjangadh

Originally built by the Bahamani Emperors between 1347-1527, this fort has rich historical significance. Popular belief is that it was also referred to as Parali Fort. It is situated at an altitude of 914 meters, has two main gates, two lakes, and mandirs of Bhagwan Ram, Hanuman, and Anglai Devi. It was later conquered by Adil Shah in the 16th century and subsequently came under the rule of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. The fort is considered the cultural capital of the Maratha King Shivaji.

Renamed from Parali Fort to Sajjangadh at Shivaji Maharaj's request, the fort became the final resting place of Samarth Ramdas, the Guru of Shivaji Maharaj. The teachings and works of Samarth Ramdas, including the renowned Dasbodh, are still followed by many in Maharashtra, giving Sajjangadh cultural importance.

Currently managed by the Ramdas Swami Sansthan, the fort and the samadhi of Samarth Ramdas are open to devotees from sunrise to sunset. The daily routine at the samadhi includes morning prayers, Abhishek, Puja, Bhajans, and readings from the Dasbodh. Every year during Shiv Jayanti, thousands of devotees visit the mandir. Devotees are provided with free accommodation at Bhakt niwas, and the mandir hosts various rituals and festivals throughout the year, including Guru Purnima, Das Navami, and Ram Navami.

Durga Devi Famine, 1396 to 1407

However, the aforementioned period of prosperity did not last long. During the Bahmani rule, a devastating famine known as the Durga Devi famine occurred. It is one of the tragic events in the district's history. The famine lasted for twelve rainless years from 1396 to 1407, leading to widespread depopulation, loss of life, and the transfer of control of strongholds from Islamic rulers to local rajas.

According to the Gazetteer (1885), during the initial years of the famine, Mahmud Shah Bahmani (1378-1390) deployed ten thousand bullocks to transport grain from Gujarat to the Deccan and established seven orphan schools in major towns within his realm. Despite these efforts, no ruler could mitigate the widespread disorder and loss of life experienced during this prolonged crisis.

Before the region could begin to recover, it was further ravaged by two consecutive rainless years in 1421 and 1422. Countless cattle perished, and unrest among the populace escalated into open revolt. The devastation was so severe that many existing villages had vanished entirely, necessitating the formation of new settlements. Land was granted to those willing to cultivate it, exempt from rent for the first year and requiring only a horse-bag of grain as payment for the second year. This resettlement initiative was overseen by Dadu Narsu Kale, an experienced administrator and a Turkish eunuch from the court.

Famine was accompanied by a series of local disturbances. In 1429, Malik-ul-Tujar, the governor of Daulatabad, led a campaign alongside deshmukhs (hereditary local officers) to restore order. Their efforts initially targeted Ramoslus in Khatav Desh and a band of bandits in the Mahadev hills. The expedition then proceeded to subdue disturbances towards Wai and Tarfhal.

Bahmani to Bijapuri Sultanate

To enhance centralised control over the Bahmani Kingdom (1463-1482), Mahmud Gawan, the Prime Minister of the Bahmani Sultanate, aimed to restructure the administration. Gawan's scheme aimed to streamline governance by distributing authority more effectively and ensuring that forts were not under the sole control of potentially rebellious governors.

According to the Gazetteer (1885), he restructured the Bahmani territories into eight provinces instead of the previous four. Satara was placed under the jurisdiction of Bijapur, one of the two divisions of Gulbarga. It was governed by Gawan himself. Each province was allocated only one fort under the governor's control, with all other forts entrusted to appointed captains and garrisons, funded and supervised centrally. The captains received substantial increases in pay and were strictly mandated to maintain full garrison strength.

In 1481, upon Mahmud Gawan's passing, his estate of Bijapur, including the district, was granted to Yusuf Adil Khan, who was a jagirdar at the time. He would later establish the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur. In 1489, Yusuf Adil Khan asserted his independence by proclaiming himself a king. Between 1482 and 1518, he successfully captured numerous forts from the governors of Mahmud Shah Bahmani II and brought the entire region from the Bhima River to Bijapur under his control.

Land Reform

One of the initial actions undertaken by the Adil Shahis in the district was land reform. According to the Gazetteer (1885), under the Bijapur kings, the country was divided into districts or sarkars, although perhaps not as consistently as during the later Mughal period. These districts were further subdivided into smaller units, often referred to in Persian as parvana, kat-yat, sammat, mahal, and taluka, and occasionally referred to as prant and desh. In the hilly west, which was typically administered by local Hindu officials, the land was organized into valleys with names such as khora, maura, and madval.

Revenue collection was primarily entrusted to revenue farmers, with some farms overseeing just one village. In cases where revenue farming was not practiced, officers were often responsible for revenue collection. An amil (government agent) supervised the revenue farmers, overseeing revenue collection, managing law enforcement, and adjudicating civil disputes.

Samarth Ramdas

Samarth Ramdas made a unique contribution to Maharashtra's spiritual and social life by advocating for Bhakti (devotion) combined with Shakti (strength). He was born Narayan Suryajipant Thosar in 1608 at Jamb (Jalna district).

He was a renowned devotee of Lord Rama and Hanuman. His primary karmabhoomi was the fort of Sajjangad in Satara district, which was gifted to him by his disciple, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. He established mathas (monasteries) across India to spread "Maharashtra Dharma" (righteous living) and inspire cultural and national consciousness. His most famous work, the Dasbodh, is a comprehensive manual for both spiritual and practical worldly life. His Samadhi at Sajjangad remains a centre for his teachings.

Rise of Shivaji

The decline of the Adil Shahi kingdom was partly caused by the constant Mughal invasions from the north (the first one being in 1631) and partly by the rebellion of Chhtrapati Shivaji Maharaj (1630-80 CE) of the Bhosale dynasty (S/o of Shahji Bhonsale, an Adilshahi Commander and Jijabai Bhonsale). Shivaji initiated his rebellion against the Adil Shah in 1646 when, at the age of 16, he captured the Torna Fort (currently in Pune). Soon enough, he became embroiled in a constant conflict with the Adil Shah.

Local Rajas of Satara

Under the Bijapur government, Satara was managed by local Maratha Chiefs such as the Mores. Chandrarao More's territory, Javli (present Jawali village in Phaltan teshil), is described as located approximately thirty-five miles northwest of Satara. Other rajas included Rav Naik Nimbalkar of Phaltan, located about thirty-five miles northeast of Satara; Junjharao Ghadge of Malavdi, approximately twenty-seven miles east of Satara; Daphle of Jath, situated around ninety miles southeast of Satara; Mane of Mahasvad, approximately sixty miles east of Satara; and Ghorpade of Kapshi on the Varna river, about thirty miles south of Karad.

Ravaji Nimbalkar of Phaltan

Ravaji Nimbalkar of Phaltan (present Phaltan tehsil) was the Naik of Phaltan. Originally surnamed Povar, he adopted the name Nimbalkar from Nimbalik or Nimlak, where the first Nimbalkar resided. The Nimbalkar family is regarded as one of the oldest in Maharashtra, as they were appointed as Sardeshmukh of Phaltan by one of the Bijapur kings before the mid-17th century. The Deshmukh of Phaltan is believed to have become an independent chief, repeatedly withholding the district's revenues. The Nimbalkars had a matrimonial alliance with Shivaji Maharaj, Sayeebai Nimbalkar was his first wife and mother of his first son Sambhaji.

Mores of Javali

Chandrarao More held a position of authority and influence in the present Jawali village. According to the Gazetteer (1885), More was initially a Karnatak chief. The Mores were, in fact, believed to be descendants of the Maurya dynasty. He was appointed during the reign of Yusuf Adil Shah (1490-1510) to lead a contingent of 12,000 Hindu infantry tasked with subduing the formidable region between the Nira and the Varna rivers. More achieved success in this endeavour and rose to prominence.

Gazetteer further notes that the descendants of Chandrarao More ruled over the same region for seven generations, and their governance led to the transformation of the once barren Jawali land into a populous area. All subsequent rulers of the More lineage adopted the title of Chandrarao.

Fall of Jawali

After Daulatrav More passed away without an heir in 1648, His widow seeked Shivaji’s help in adopting Yashwantrao (a young child from the Shivtar branch of the family) and carrying forward Jawali’s administration during his minority with the assistance of Hanmantrao More, a distant relative. In course of time Yeshvantrao grew jealous and impatient due to Shivaji’s interference.

In the year 1654, Shivaji decided to take care of the problem of Jawali. After the Mores refused the terms sent by him, Shivaji sent a small force to intimidate them. When this did not yield any results, he sent another force; this time, a small battle took place near Jawali, in which Jawali’s forces were routed and Hanmantrao was killed. Yashwantrao fled to the fort of Rairi (now in Raigad district). In the meantime, Shivaji quickly seized Jawali and sent forces to confront him. Inviting Yashwantrao to negotiate, Shivaji captured him along with his two sons. Yashwantrao was executed, and his sons were imprisoned and taken to Pune. Soon after

The conquest of Jawali ended with the submission of the Shivthar valley and the capture of the formidable Vasota fort, located approximately fifteen miles west of Satara, renamed as Vajragad by Shivaji. G.S. Sardesai, in his Volume 1 of the ‘New History of the Marathas’, mentions that Yashwantrao's sons were put to death for maintaining clandestine communication with Bijapur.

Pratapgadh

After taking control of Jawali, Shivaji constructed the famous Pratapgadh. It is one of the most beautiful hill forts in the district. The fort holds significant historical importance in the Maratha Empire's history.

According to the Gazetteer (1885), in 1656, to secure access to his possessions on the banks of the Nira and the Koyna and to strengthen the defences of the Par pass, Shivaji pitched upon a high rock near the source of the Krishna, on which he resolved to build another fort. The execution of the design was entrusted to a Deshastha Brdhman named Moropant Trimbak Pingle, who, shortly before, had been appointed to command the fort of Purandhar in Poona. This man, when very young, had accompanied his father, then in the service of Shahaji to the Karnatak and returned to the Maratha country about the year 1653 and shortly after, joined Shivaji. The able manner in which he executed everything entrusted to him soon gained him the confidence of his master and the erection of Pratapgad.

The strategic location of Pratapgadh, built on a high spur overlooking the road between the villages of Par and Kinesvar, provided a natural defensive advantage to the Marathas. It is believed that the fort's construction was a well-thought-out move by Shivaji, as it allowed his forces to camp behind its walls, utilising the thick forests and steep hills that surrounded it to their advantage during battles.

Battle of Pratapgadh

As soon as the construction of Pratapgadh fort was completed, conflicts that had been brewing between the Adil Shahi and Marathas erupted. The Adil Shahi of Bijapur perceived Shivaji as a threat and aimed to confront him. The Adil Shah in 1658 sent a vast force under the leadership of Afzal Khan to intimidate and subdue Shivaji. Afzal Khan before putting up a camp in Wai (on the foothills of Pratapgad) is said to have desecrated the temples of Tuljabhavani in Tuljapur, the Vithal temple in Pandharpur and the Shiv mandir in Shikhar Shingnapur. The Battle of Pratapgad that followed, was a significant event where Shivaji faced Afzal Khan's large army, including cavalry, infantry, musketeers, cannons, camels, and elephants. Despite being outnumbered, Shivaji's strategic positioning and the fort's defenses enabled the Marathas to emerge victorious. The battle not only secured a crucial military triumph for the Marathas but also marked the beginning of the Maratha Empire's expansion and growth under Shivaji's leadership.

In the years following the battle, Pratapgadh remained an important strategic fort for the Maratha Empire. Small temples were built inside the fort, and in 1957, a 17-foot-tall equestrian bronze statue of Shivaji was erected. The fort continues to be a popular tourist destination, offering panoramic views of the Konkan coast and housing important historical sites like the Bhavani Temple and Afzal Khan's tomb.

The Meeting with Afzal Khan

At dawn, Afzal Khan, a general of the Adilshahi Sultanate, established his camp with an army of over 10,000 horsemen in the valley below Pratapgad. Advancing into Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s territory, his objective was to suppress the growing Maratha power by targeting key Hindu religious and economic centers. His campaign involved the destruction of temples, confiscation of wealth, and persecution of Hindu pandits and merchants. As he moved through the rugged terrain of Maharashtra, Afzal Khan sought to provoke Shivaji into open battle.

Shivaji, known for his strategic acumen, avoided direct confrontation and instead maneuvered to draw Afzal Khan into the forested and hilly terrain around Pratapgad, where the Marathas held a tactical advantage.

When military pressure failed to produce results, Afzal Khan proposed a personal meeting under the pretext of diplomacy, sending Krishnaji Bhaskar as his envoy. Aware of Afzal Khan’s previous dealings with other rulers, Shivaji approached the proposal cautiously and dispatched his own envoy, Gopinath Pant, to negotiate the terms. It was agreed that both leaders would meet in a private tent on the slopes of Pratapgad. Shivaji attended the meeting equipped with a concealed wagh nakh (tiger claw weapon) and the sword Bhavani, worn beneath a protective chilkhat (chainmail coat).

During the meeting in the tent, Afzal Khan attempted to stab Shivaji with a concealed dagger, as recorded in the Sabhasad Bakhar. Anticipating possible treachery, Shivaji had worn concealed armor beneath his garments, which prevented the blade from causing injury. In response, he used his wagh nakh (tiger claw weapon) and the sword Bhavani to strike Afzal Khan in the abdomen and neck, inflicting severe wounds. As Afzal Khan retreated, Shivaji’s bodyguard, Jiva Mahala, intervened and killed him when one of Afzal Khan’s armed attendants moved to attack.

Following Afzal Khan’s death, his forces became disorganized, enabling the Marathas to launch a planned assault. The ensuing engagement ended in a decisive Maratha victory, significantly enhancing Shivaji’s political and military standing and marking a pivotal moment in his struggle against the Deccan Sultanates.

Bhavani Mandir

Around 1661, the construction of the Bhavani Mandir at Pratapgadh took place perhaps due to Shivaji's profound devotion to Bhavani devi. There is a story behind how the mandir came about in the town. According to the Gazetteer (1885), during the rainy months of 1661, Shivaji was unable to visit the Bhavani mandir at Tuljapur. Therefore, he took the initiative to honour Bhavani Devi by dedicating a mandir to her within his own domain. For this purpose, he chose Pratapgadh as the site for the mandir.

Shivaji had to fight a few conflicts in the 1670s, with local cheifs such as the Nimbalkars and Ghatges of Phaltan and Malvadi respectively a few times to gain complete control over the land that now consist of the district of Satara.

Ajinkyatara Fort

Ajinkyatara Fort, also known as the "Fort of the Sapta-Rishi," is a historic hill fort situated atop Ajinkyatara Mountain, one of the seven peaks surrounding Satara. Believed to have been built in the 16th century by Raja Bhoj of the Silhara dynasty—a royal lineage that ruled parts of the Konkan region from the 8th century CE—the fort's early history in Satara remains partly speculative, as direct evidence of Silhara rule here is lacking.

Over the centuries, Ajinkyatara became a coveted stronghold due to its strategic location, defensive strength, and symbolic importance. In 1673, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj captured it from the Adil Shahis of Bijapur. From 1700 to 1706, the fort fell under the control of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, before being recaptured by Shahu Maharaj in 1708. It remained under Maratha control until the British conquest in 1818. Tradition holds that Queen Tarabai (regent queen and mother of Shivaji I of Kolhapur) briefly seized the fort from the Mughals and renamed it Ajinkyatara. The fort also served as her prison later on.

Near the fort lies Char Bhinti, a site of both royal and nationalist significance. Originally known as the ‘Nazar Mahal,’ it was first viewed by Chhatrapati Pratap Sinha Maharaj in 1830 as a vantage point for royal women to watch the Vijaya Dashami procession. Later, it was transformed into a Martyr Memorial dedicated to heroes of the 1857 War of Independence, such as Rani Lakshmibai, Tatya Tope, and Rango Bapuji Gupte. Featuring four surrounding walls and a central pillar, the memorial was established to mark the centenary of the uprising and refurbished in 2001, now standing as a reminder of both Satara’s royal heritage and its role in India’s freedom struggle.

Kamalgadh

Kamalgadh, also known as Bhelanja or Kattalgad, is a square hill fort located near Wai in the district. Exact details about its construction are unknown, but it is believed that it was built during the Maratha times. The fort stands at an elevation of over 4511 feet and offers a good view of the surrounding area. Perhaps, like any other fort, it served as a strategic defensive location.

In the context of the Third Anglo-Maratha War, the fort was surrendered to a British army commanded by Major Thatcher in 1818, and was subsequently used as a prison for prisoners of war under British rule. The fort covers a flat area of nearly 3-4 acres and is surrounded by thick woods and steep rocks that need to be carefully scaled to reach its base. Unlike other forts in the area, Kamalgad lacks buildings, walls, or gateways on top, with the only structure being a well sunk through the rock, which still contains water and was used for punishing criminals.

Under Sambhaji I and Rajaram I

After the death of Chhatrapati Shivaji in 1680, his elder son Sambhaji ascended the throne following a brief succession dispute with his stepmother Soyarabai, who sought to place her own son, Rajaram I, on the throne. During his short reign (1681–1689), Sambhaji was engaged in constant warfare against the Mughals, the Portuguese, and other regional powers.

The fall of Bijapur in 1686 and Golconda in 1687 brought the Maratha kingdom under increasing Mughal pressure, with several smaller forts, such as Tathvad, falling to Aurangzeb’s forces. In 1689, Sambhaji was captured and executed by Aurangzeb. The throne then passed to Rajaram I, who was crowned as the heir since Shahu I (Sambhaji’s only son) was considered too young to rule. Soon after, Raigad fell to the Mughals (1689), forcing Rajaram I to flee to the southern fort of Jinji. Yesubai (Sambhaji’s widow) and Shahu I were captured by the Mughal commander and were imprisoned.

During his time at Jinji, Rajaram created the office of Pratinidhi (King’s Representative). Maratha officers such as the Pratinidhi worked diligently to restore forts and inspire the garrisons. The Pantpratinidhi frequently moved between locations; he finally established his principal residence at Satara.

In January 1698, Jinji fell to the Mughals after a prolonged siege, but Rajaram managed to escape to Vishalgad in Kolhapur. In 1699, he briefly stayed in Satara, which, on the Pantpratinidhi’s advice, was made the seat of government. He then marched north on military expeditions. Aurangzeb, upon learning of Rajaram’s movements, advanced west from Brahmapuri in Solapur and encamped near the fort of Vasantgad, about seven miles northwest of Karad.

In early 1700, Aurangzeb laid siege to Ajinkyatara, which surrendered in April, a month after Rajaram’s death, and remained under Mughal control until 1706. Maharani Tarabai assumed control of the Maratha kingdom after her husband’s death as a regent of her son Shivaji I of Kolhapur and carried forward the resistance against Mughal forces. It is also believed that she took back Ajinkyatara and the surrounding regions, bringing Satara back into the folds of the Maratha kingdom.

The Aundh State

The Aundh state was located 41 kms from the city of Satara. The Rajas of Aundh held the title of ‘Pant Pratinidhi’(literal meaning is representative), a ministerial position in the cabinet of the Maratha Empire. Interestingly, this position was created during the reign of the third Chhatrapati i.e, Rajaram I. The Pant Pratinidhi was tasked with representing the king and governing in the king’s absence.

The Aundh State came to be after the conflict between Tarabai and Shahu I of Satara over the Maratha throne was concluded, and Shahu had emerged victorious. The elder brother, Shripatrao, loyal to Shahu I, became his Pant Pratinidhi. His loyalty was rewarded with the grant of the Aundh jagir. Later on, his family came to be known as the ‘Rajas of Aundh’, though their power and importance in the larger Maratha empire were downgraded to equal the status of a local chieftain.

In 1818, after the third Anglo-Maratha war, the East India Company abolished the Peshwai, and the state of Satara was given to the Chhtrapati. Aundh remained as a jagir under it. In 1848-49, when Satara was annexed under the Doctrine of Lapse, the Aundh state became a princely state in its own right. In the 1930s, the state undertook a democratic experiment, endorsed by Gandhi, which proved to be moderately successful.

Chhatrapatis of Satara

After the death of Aurangzeb in March 1707, Prince Azam Shah released Shahu from Mughal captivity. Shahu returned to Maharashtra, where many Maratha chiefs rallied behind him as the rightful heir to the Maratha throne. His claim was strongly opposed by Rani Tarabai. As a culmination of this, in October 1707, he faced Rani Tarabai’s forces at the Battle of Khed (in present-day Pune). Tarabai was decisively defeated, largely due to the last-minute defection of the influential Maratha commander, Dhanaji Jadhav. Shortly after, she also lost control of the strategic fort of Satara (Ajinkyatara).

Shahu established Satara as the new capital of the Maratha kingdom and was formally crowned Chhatrapati in January 1708. By 1710, the political division of the Maratha state into two principalities, Satara under Shahu and Kolhapur under Tarabai, had become a reality.

However, Tarabai and her son Shivaji II were soon overthrown by Rajasbai, another widow of Rajaram, who in 1714 installed her son, Sambhaji II (styled as Sambhaji I of Kolhapur), as the ruler of Kolhapur.

For a brief period, Sambhaji I of Kolhapur entered into a secret alliance with the Nizam of Hyderabad in an attempt to challenge Shahu's supremacy. This alliance collapsed after the Nizam’s defeat by Peshwa Bajirao I in the Battle of Palkhed (1728), which forced him to sign the Treaty of Mungi-Shevgaon and withdraw his support for Sambhaji I. It is also believed that Tarabai had decided to move to Satara itself. The rivalry between the Satara and Kolhapur branches was formally resolved in 1731 with the signing of the Treaty of Warna. Through this agreement, both parties recognized each other’s authority. Shahu ceded territory between the Krishna and Tungabhadra rivers to Sambhaji I. At the same time, Kolhapur accepted a vassal relationship under the suzerainty of Shahu.

Shahu I, 1707–1749

Shahu I (Shahu Ji), the grandson of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, ruled from Satara from 1707 until his death in 1749. His rule marked the transition of the Maratha Empire from a centralized monarchy to a more decentralized confederacy, where power was shared with the Peshwas and regional chieftains.

Shahu Ji (Shahu I) was the son of Sambhaji Maharaj, who was captured and executed by Aurangzeb in 1689. As a child, Shahu was taken prisoner by the Mughals and kept in captivity in Aurangabad and Delhi for nearly 18 years. While Shahu remained in Mughal captivity, Rajaram I (the younger son of Shivaji Maharaj) who had been leading the Maratha Empire, died in 1700. Following his death, Tarabai, his widow, assumed power as regent for her young son, Shivaji II, and began ruling from Satara. With Shahu still imprisoned, Tarabai effectively became the de facto leader of the Maratha Empire, guiding it through a critical and turbulent period. But this did not last long.

Satara became the capital of Shahu’s kingdom. His authority was recognized across the Maratha territories, but he relied heavily on Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath and, later his successors. Maratha Empire expanded under his rule, particularly under Bajirao I (1720-1740). Chhatrapati Shahu ruled Satara until 1749. He had two adopted sons—Ranoji Lokhande, renamed Fatehsinh I, and Rajaram II of Satara (1726–1777), who succeeded him as Ramaraja Chhatrapati. Rajaram II had been brought to Shahu by Tarabai, who initially claimed he was her grandson through Shivaji I of Kolhapur and thus a direct descendant of Shivaji Maharaj. When he refused to serve her political ambitions, she denounced him as an imposter, only to later acknowledge his legitimacy before the Maratha sardars.

Rajaram II, 1749–1777

Rajaram’s period is particularly interesting because it highlights a period of political intrigue, shifting power dynamics, betrayal, war, and empire-building within the Maratha Empire.

Rajaram II was adopted heir of Shahu ji but his origins were unclear. It is believed that it was to counter the power of the Peshwas, Queen Tarabai(see Kolhapur for more) brought forward a young boy named Rajaram II and claimed that he was her grandson (the son of her late son, Shivaji I of Kolhapur). This claim gave Rajaram II legitimacy, as he would be considered a direct descendant of Shivaji Maharaj through Tarabai’s lineage. Since Shahu I had no natural heir, and the Peshwas needed a Chhatrapati for political stability, Rajaram II was accepted as the new Chhatrapati of Satara.

According to the Gazetteer (1885), In 1751, just two years after installing Rajaram II, it was argued that Tarabai suddenly disowned him. It is argued that she publicly declared that Rajaram II was not her grandson and was an imposter. This confession shocked the Peshwas, as it weakened Rajaram II’s legitimacy and created a political crisis.

Rajaram II, despite being officially the Chhatrapati, was left powerless under Peshwa dominance. Subsequently, according to the district Gazetteer (1885), “Poona took the place of Satara as the capitals of Marathas”. The Third Battle of Panipat (1761) was fought during Rajaram II’s reign, in which the Marathas were defeated by Ahmed Shah Abdali. The following Chhatrapati Shahu II (1777–1808) is argued to have remained a nominal ruler, with the Peshwas controlling all state affairs from Pune.

Pratapsingh, 1808–1839

In the early 19th century, Chhatrapati Pratapsingh was known for his resistance against British interference in Maratha affairs. He attempted to preserve the independence of Satara, even after the fall of the Peshwas and the defeat of the Marathas in the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-1818). The British East India Company had defeated Peshwa Baji Rao II and annexed his territories, ending the Maratha Confederacy. The British did not abolish the Chhatrapati's title in Satara, but they reduced it to a British-controlled princely state. Pratapsingh was restored as Chhatrapati by the British in 1818, but he was expected to govern under British supervision, which he attempted to resist.

Pratapsingh was considered a just and capable ruler. He undertook various developmental projects, including road construction, aqueducts, and waterworks at Mahabaleshwar and Satara. According to the Gazetteer (1885), his rule was described as orderly and prosperous, receiving praise from British officials like Mr. Elphinstone.

Pratapsingh faced deposition in 1838 as the British suspected that he was in contact with the exiled Peshwa Baji Rao II, who was living under British surveillance in Bithoor (presently in Uttar Pradesh). According to the Gazetteer (1885), the British suspected that he was plotting against their rule and was involved in secret correspondence with various Indian leaders, including Mudhoji Bhosale, the ex-Raja of Nagpur. He was also accused of conspiring with European powers, including the Portuguese in Goa, France, Russia, and Austria (to form an anti-British alliance). The British claimed that he had promised territories to Portugal in exchange for military assistance. He was officially deposed on 5 September 1839, under the orders of Sir James Carnac, the Governor of Bombay. He was first imprisoned at Vasota Fort before being sent into exile in Benares (Varanasi), where he eventually died in 1847.

His sibling, Shahaji, assumed the throne. However, it is argued that as Pratapsingh approached death, he attempted to adopt an heir, Venkatji, from the Bhonsle family. However, the British refused to recognize this adoption, stating that the sanction of the paramount British power was necessary to validate it. Instead, they supported Shahaji’s claim as the legitimate successor to the Satara throne.

The treaty of 1819, which had initially recognized Pratapsingh as the ruler, was interpreted by the British to justify their control over succession. Even though Shahaji was considered a possible successor, the British eventually decided to annex Satara in 1848. Satara emerged as the first local ruling entity annexed by such legal expansionism. This was done under the Doctrine of Lapse, a British policy stating that if a ruler died without a direct male heir, the kingdom would be annexed. Despite supporting Shahaji’s claim, the British denied him the throne, marking the end of the independent rule of Satara.

Rajwadas of Satara

The two rajwadas located in Shukrawar Peth, Satara, known as the Old Palace (Juna Rajwada) and the New Palace (Nava Rajwada), are important landmarks that reflect the city’s Maratha heritage. These structures stand as reminders of Satara’s role as a center of Maratha power, administration, and cultural life.

Juna Rajwada

The Juna Rajwada, or Old Palace, was built in 1824 by Raja Pratapsinh of Satara. It represents traditional Maratha architecture, with features like large terraces, balconies, and detailed stonework. Rising 50 ft. above the ground, the rajwada could be seen from over a mile away to the east. A large cistern was built into the right wing for the use of its residents, reflecting the thoughtful planning that went into royal residences of the period.

This rajwada once served as the seat of local administration and was central to important events in Satara’s history. During the famine of 1876–77, it was used as a relief center, providing shelter and aid to the people of the region. In later years, it was repurposed to house the Government High School, now known as Pratapsinh High School, as well as primary schools, municipal offices, and other government departments.

Despite changes in its use over time, the Juna Rajwada retains its historical significance, offering a window into the Maratha era’s architecture and royal life.

Nava Rajwada

The Nava Rajwada, or New Palace, was built between 1838 and 1844 by order of Raja Shahaji. It was designed by a British engineer named Mr. Smith, who also oversaw the construction of several bridges in Satara during the same period. The New Rajwada reflects the changing influences of the 19th century, blending traditional Maratha elements with newer architectural styles.

The structure has a distinctive façade adorned with traditional motifs, though many have eroded over time. Inside, a large courtyard is surrounded by a broad colonnade, with a grand hall supported by 64 teak pillars on its western side. These pillars were once richly decorated with brocade and gold embroidery during royal functions. A separate audience hall at the upper end of the courtyard was dedicated to Devi Bhavani, the kuldevi of the Marathas. The rajwada also once housed Bhavani, the famous sword of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, kept in a richly carved room near the colonnade.

After coming under British control in 1876, the rajwada served various administrative functions. It housed the district and sessions courts and other offices such as the treasury, Satara City Survey Office, and the Divisional Forest Office. Although it is now undergoing changes in function, the rajwada remains an important part of Satara’s architectural and historical legacy.

Together, these two rajwadas preserve the layered history of Satara—its role in the Maratha Empire, the adaptations during British rule, and the continued pride of local residents in their city’s past.

Krishna-Venna Sangam

Krishna-Venna Sangam, also known as Sangam Mahuli, is located about 5 km east of Satara city, at the confluence of the Krishna and Venna rivers. This site is home to a group of 18th and 19th-century mandirs built in typical Maratha architectural style, characterized by basalt stone construction, carved domes, and arcaded passageways. The meeting of the two rivers, combined with the historical and religious importance of the site, makes it an important yatra destination in the region.

The establishment of the mandirs at Sangam Mahuli is closely associated with the patronage of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, who granted the land to his minister, Shripatrao Pant Pratinidhi. The mandirs were built over time by Shripatrao and other local Brahmins, making this area both a religious centre and a symbol of Maratha-era patronage. Sangam Mahuli is also remembered for its connection to historical events, such as the meeting between Bajirao II and Sir John Malcolm before the Third Anglo-Maratha War, and is known as the birthplace of Ramshastri Prabhune, an important figure in Maratha history.

Vishveshwar Mandir

The most prominent Mandir at Sangam Mahuli is the Vishveshwar Mandir, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv in the form of Vishveshwar. Built in 1735 CE by Shripatrao Pant Pratinidhi on land donated by Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, this stone-built structure exemplifies the Hemadpanthi architectural style seen across the region. The layout consists of a sabhamandap (assembly hall), antarala (vestibule), and garbhagriha, with murtis of Ganesh and Parvati placed in niches along the passageways. The shikhar is crowned with fluted domes and decorated with stucco figures, with miniature replicas clustered around the central tower. In front of the Mandir stands a striking 60 ft. deepastambha, carved from a single stone with niches for oil lamps. A separate small Nandi mandap with an intricately carved dome completes the composition.

An arcaded passageway runs along two sides of the Mandir, with hidden stairways leading to its upper levels. From here, visitors can get elevated views of the complex and the surrounding confluence of the Krishna and Venna rivers.

Rameshwar Mandir

Another significant Mandir at the Krishna-Venna sangam is the Rameshwar Mandir, situated by the Krishna river, in the village of Kshetra Mahuli. Also dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv, it is smaller than the Vishveshwar Mandir but holds local significance. Built in the Nagara style with brick and lime, its shikhar rises over a garbhagriha housing a Shivling, surrounded by the waters of the Krishna during certain seasons. Like its counterpart across the river, it has a sabhamandap with murtis of Ganesha and Parvati, a Nandi mandap, and a stone deepastambha.

Memorial of Maharani Yesubai

Sangam Mahuli is not only significant for its religious importance and architectural heritage but also for its association with one of the most powerful women of the Maratha Empire—Maharani Yesubai. The wife of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj and mother of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, Yesubai, was imprisoned by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb for 29 years. After her release, she is believed to have arrived in Satara around 1729 CE, where she spent the remainder of her life.

For many years, the exact location of Maharani Yesubai’s memorial remained unknown. However, recent research conducted by Satara-based historians and organisations such as the Jidnyasa Itihas Sanshodhan ani Sanvardhan Sanstha has led to the identification of her tomb at Mahuli, near the Krishna-Venna Sangam. The site features a stone Vrindavan and dome, marking the final resting place of this important historical figure.

In recognition of its significance, the Government of Maharashtra has recently declared the site as a state-protected monument. Conservation efforts are expected to begin in the coming years under the supervision of the state archaeology department. Today, this memorial stands as a testament to Maharani Yesubai’s resilience, as well as her role in shaping the history of Satara and the Maratha Empire.

Phaltan Rajwada

Phaltan Rajwada is located in Phaltan, around 60 km from Satara. Traditional Maharashtrian wadas, or mansions, represent a lifestyle long gone, and among them, royal palaces or rajwadas are even rarer. While many such structures across Maharashtra have disappeared or lie in ruins, Phaltan Rajwada, formally known as Madhoji Manmohan Rajwada, after the one who built it, remains a rare example that has survived.

From the 13th century CE to 1947, Phaltan was the seat of the Naik Nimbalkar dynasty, a family that played an important role in the region’s history for over 700 years. The dynasty traces its origins to an adventurer named Nimbra, a member of the Parmar Rajput clan from Malwa in Central India. Around 1270 CE, Nimbra arrived in the Deccan and established a principality at the foot of the Bhambhumahadev range, an offshoot of the Sahyadris. His descendants later settled at Nimblak, a village near Phaltan, giving the family its surname, ‘Nimbalkar.’

By 1327 CE, Nimbra’s grandson Nimbraj II had received a jagir (land grant) and the title ‘Naik’ from Sultan Muhammad Bin Tughlaq in recognition of his family’s service in battle. Over the centuries, the Naik Nimbalkars developed close ties with the Marathas, especially after the marriage of Saibai Nimbalkar to Shivaji Bhosale in 1640 CE. Phaltan remained a feudatory of the Chhatrapatis of Satara until 1849, when Satara was annexed by the British, making Phaltan a princely state under the Crown. Major Shrimat Malojirao Naik Nimbalkar was the last ruling Raja of Phaltan before it acceded to India in 1947. The royal family remained politically influential in the region, and this continuity helped preserve Phaltan Rajwada as a seat of local authority and cultural life.

Construction of the Phaltan Rajwada began in 1861 and was completed in two phases by 1911. It replaced an earlier wada of the family on the same site. The palace, named after Madhoji Manmohan Naik Nimbalkar, blends Jain, Hindu, and Western styles, reflecting changes in architecture during that period. Its Indo-Saracenic design, with domes, circular pillars, and Gothic features, marks a shift from traditional designs to modern forms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The main building is a two-storey structure, with courtyards on the ground floor, halls on the first floor, and bedrooms on the second floor. Prominent parts of the residential section include the Darbar Hall, Surucha Hall, Hirva Hall, Badami Hall, Saatkhani Laxmi Terrace, and Gulabi Hall. The walls feature paintings of Naik Nimbalkar rulers, including depictions of Maharani Saibai. The woodwork of the Rajwada stands out for its fine carvings of parrots, peacocks, and lions, and its halls are decorated with glass chandeliers. The palace also houses objects from the family’s hunting expeditions.

One of the most unusual events held here was the celebration of King George V’s coronation in 1911. Along with ceremonies in Delhi and London, Phaltan also held a grand procession and durbar. A portrait of the British monarch was paraded through the town on an elephant, followed by a durbar held in the Shri Ram Mandir inside the Rajwada, where the portrait was ceremonially blessed.

Shri Ram Mandir

An important feature of the Rajwada is the Shri Ram Mandir, located within its complex. The Mandir is over 225 years old and built in the Hemadpanti style. It has an east-facing entrance, surrounded by a tall stone wall, and features three deepmala (lamp towers) at its front. The garbhagriha contains beautiful murtis of Ram, Sita, and Laxman. Adjacent to the Shri Ram Mandir are smaller mandirs dedicated to Radhakrishna, Ekamukhi Datta, and Garuda. Over generations, this Mandir has been a key religious site for the local community, with its festivals drawing people from the town and surrounding areas.

The chowk surrounding the Rajwada remains an active space shaped by these religious and historical layers. Today, the Phaltan Rajwada is managed by the Naik Nimbalkar Devasthan trust, which oversees its religious and charitable functions.

Colonial Period

From 1849, Satara was directly under the control of the British. According to the Gazetteer (1885), the earliest British possession in the Satara district (as of 1883) included sixteen villages in the Tasgaon sub-division. These villages were acquired in 1818 after the British overthrew the Peshwa post 3rd Anglo-Maratha War. In 1829, the Raja of Satara ceded more land in Malcolmpeth in exchange for other territories. The rest of the Satara district lapsed to British control between 1837 and 1848, as discussed above.

Formation of Satara District, 1848

Initially, the area was not classified as a collectorate or district, but rather a larger province under British administration. The British placed it under a Commissioner and divided it into eleven subdivisions, including Bijapur, Javli, Karad, Khanapur, Khatav, Koregaon, Pandharpur, Satara, Targaon, Valva, and Wai.

It was in 1856, through a revision that led to the creation of twelve mahals (small divisions). In the process of reconstructing a district, the villages were redistributed, and twelve new administrative officers (mahalkaris) were appointed. In 1862-63, Bijapur was transferred to Belgaum, and Tasgaon was moved from Belgaum to Satara. In 1864-65, Pandharpur was moved to Sholapur. In 1867, the Targaon sub-division was abolished, and its eighty-three villages were redistributed among Karad, Koregaon, Satara, and Patan. In 1875, Malshiras was moved to Sholapur. By 1884, the district had eleven subdivisions: Javli, Karad, Khanapur, Khatav, Koregaon, Man, Patan, Satara, Tasgaon, Valva, and Wai.

Mahabaleshwar: Summer Capital of Bombay Presidency

During the period, Mahabaleshwar emerged as a significant site under British rule, serving as the summer capital among other roles. Its strategic importance increased, where colonial influences intersected with efforts to develop infrastructure and recreate familiar cultural landscapes. The British administration aimed to recreate the English landscape in the hill stations, introducing European fruits such as strawberries and constructing amenities like libraries, theatres, boating lakes, and sports grounds.

According to the Gazetteer (1885) , its location in the Western Ghats made it an attractive destination for British officials seeking respite from the heat and humidity of the plains. The recommendation of Colonel Lodwick and subsequent visits by high-ranking British officials highlighted its appeal. Initially, the British saw it as a favourable location for a sanatorium, and later, designated it as the summer capital of the Bombay Presidency.

The British had an eye on Mahabaleshwar as early as 1828. It was during this period that the Raja of Satara was granted alternative villages in exchange for the British acquiring Mahabaleshwar. Later Mahabaleshwar was renamed as Malcolm Peth after the governor’s name.

The prominence of Mahabaleshwar grew as British officials from the Bombay Presidency, including Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone, Arthur Malet (whose seat at "Point Arthur" is named after him), Carnac, and others, began visiting regularly from 1828 onwards.

In 1842, Venna Lake was constructed to harness water from perennial springs, with the Venna River flowing from this lake. Bartley Frere, the commissioner of Satara in the 1850s, facilitated the construction of the road from Satara to Mahabaleshwar. The construction of Venna Lake for water collection, the building of roads, and other infrastructure projects facilitated the accessibility and development of Mahabaleshwar.

“First War of Independence”, 1857

The Indian Revolt of 1857, also known as the First War of Independence, was a significant uprising against British rule that primarily affected the northern and central regions of India. The district equally played an important role. According to the Gazetteer (1885), Pratapsingh's family, their supporters attempted to rise against the British during the widespread Revolt of 1857. It is argued that Rango Bapuji gathered a group of armed men in the forests near Parli and planned attacks on Satara, Vasota, Mahabaleshwar, and other locations. The objectives of the uprising included massacring all Europeans in the region, plundering the British treasury, and freeing Pratapsingh’s family from imprisonment. Unfortunately, before the plan could be executed, British intelligence intercepted the plans and took preemptive action, preventing a full-scale attack.

After the Revolt had subsided, Shahu, the adopted son of Pratapsingh, was allowed to return to Satara with his wife Anandibai. Whereas Venkatji, the adopted son of Shahaji, was exiled—first to Ahmadabad and later to Ahmednagar in 1859-1860. The British provided monthly allowances to certain individuals during the period:

- £10 (Rs. 100) to Shahu

- £5 (Rs. 50) to Durgasing

- £3 (Rs. 30) to Kaka Saheb

- £10 (Rs. 100) to Rani Rajasbai

- £4 (Rs. 40) to Gunvantabai

- Some old servants of Pratapsingh were pensioned at a total cost of £73 (Rs. 730), while others were discharged with gratuities of £153 (Rs. 1530).

Subsequently, Venkatji died in 1864, leading Shahaji’s widow to adopt another son, Madhavrao, who became known as Aba Saheband. He later had a son named Shivaji. Additionally, one prominent figure from the district was Rango Bapuji Gupte, a diplomat and revolutionary born into a Marathi Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu family. After the British dissolved the state of Satara in 1839, Gupte was sent to England to defend the case before the British Parliament, where he stayed for 14 years without much success. Upon his return to India, he contributed towards the 1857 revolt, collaborating with leaders like Nanasaheb Peshwa and Tatya Tope. It is argued that Gupte focused on building armed organizations in regions including Satara, Kolhapur, Sangli, and Belgaon. However, when his plans were exposed, many of his recruited fighters were killed, and Gupte went underground. In 1857, during a religious ceremony at a relative's residence in Thane, British authorities attempted to arrest him. Gupte escaped in the disguise of an old woman and was never found again. In his memory, Jambhali Nakahasa has been named Rango Bapuji Chowk, and a memorial named 'Char Bhinti' in Satara honors him.

Local Administration

According to the Gazetteer (1885) the district’s land revenue was managed through eleven sub-divisions (Talukas), overseen by seven covenanted assistants. Additional administration included Mahalkaris, who managed smaller divisions like Shirala in Valva and Khandala in Wai. Mahalkaris earned salaries between £60 (Rs. 6000) and £72 (Rs. 7200) then.

Village administration was managed by hereditary village headmen (Patils or Kulkarni). Headmen handled revenue collection and policing duties. 786 accountants (Kulkarnis) were employed, with most being hereditary. A total of 3,171 village servants were recorded to be employed for policing, revenue collection, and maintaining order. Annual payments to headmen and their families totaled £647 (Rs. 67,000), while village accountants received £527 (Rs. 58,270). The total cost of village administration was £16,669 (Rs. 1,66,690) then.

Revenue Administration

According to the Gazetteer (1885), land tenure systems in the district under British rule were categorized into different types of land ownership and usage rights.

Mirasi Tenure (Hereditary Landholding)

The Mirasi system was the most prevalent form of tenure in Satara. Mirasdars, or hereditary landlords, held perpetual rights to their land, which they could mortgage or sell while continuing to pay government dues. The British administration did not interfere in the sale or transfer of mirasi lands, and purchasers of such land became responsible for paying the revenue to the government.

Categories of Mirasdars

There were two main classes of mirasdars. The Patil Vatandars (elite landlords) enjoyed special privileges, including a share of the village rent (inam), and were attached to the position of village headman, holding traditional honors. The Thalkari or Kunbi Vatandars (regular hereditary landowners) were farming families who did not hold the headman position but enjoyed the same landholding rights as Patil Vatandars.

Mirasdars could not be removed from their land as long as they paid their revenue. They influenced village affairs, were exempt from certain taxes and dues to the headman, and possessed rights such as grazing cattle on village commons, building houses on village land, and holding a share in the village site.

If a mirasdar remained in the village, he was required to pay rent. If he left or became insolvent, other mirasdars were responsible for paying his dues. If he returned, he could reclaim his land. The government preferred to auction mirasi lands for revenue rather than lease them, although sales required official approval. In some cases, British officials granted new mirasi rights at reduced rates to encourage cultivation.

All mirasi lands were heavily taxed to sustain the privileges associated with the tenure. These lands were regularly assessed, and landlords were required to pay revenue promptly.

Upri (Casual Tenure)

Upri's tenure was temporary and held entirely at the discretion of the government. Holders of upri lands could be evicted at any time, and rent was negotiated, often at a rate lower than the standard assessment.

There were two types of upri lands. Casual upri tenants were often new settlers or landless farmers who lacked the privileges of mirasdars. While they could build houses, they could neither sell them nor remove them, as the land remained the property of the mirasdar or the government. In some cases, if an upri tenant successfully cultivated the land over time, he could gain mirasi status. This policy was used to encourage settlement and cultivation.

Sheri (Crown Lands)

Sheri lands were directly controlled by the government, either taken from previous landowners or retained for state purposes. These lands were used to generate revenue or were granted to favored individuals.

Forms of Tenure

The right to occupy land could be based on hereditary ownership (Mirasi, Inam) or lease/rent-based tenure (Istava, Sheri, Upri). This system allowed the British to maintain firm control over land revenue while preserving traditional village hierarchies.

Prison for Chinese and Malaya convicts

Mahabaleshwar was known to have a prison that housed convicts from China and Malaysia in the region. They contributed significantly towards the development of districts in terms of labour and skill thereby impacting various aspects of life during the colonial period and beyond. According to the Gazetteer (1885), in the early 19th century, after the establishment of the station, a jail was set up for Chinese and Malay convicts due to concerns about the detrimental effects of the climate in Pune and Thane on their health. The jail, built to accommodate around 120 prisoners, was described by Dr. Winchester in 1830 as follows in the gazetteer:

It was constructed in a quadrangular layout with an inner paved courtyard. The front side, serving as the entrance, housed rooms for the guard of sepoys, offices for jail authorities, and two rooms used as solitary cells or for prisoners requiring special care due to illness. The other three sides of the jail comprised long, airy apartments accessible only from the inner courtyard. Two of these sides were typically occupied by prisoners, while the third served as a storage and work area. The jail was situated on the site currently occupied by the Engineer’s store.

The Gazetteer records that various Superintendents noted that the prisoners, despite being convicted of serious crimes such as murder, piracy, and robbery, were generally well-behaved and compliant. Each convict received a daily ration of food. During working hours, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., they were required to work for the government. Except for a few exceptions, they were confined to their quarters by six in the evening, although lights were allowed until later hours. During leisure time, they were permitted to visit the bazaar to obtain provisions. Many took advantage of this opportunity to cultivate potatoes and other English vegetables in nearby fields, which they were allowed to sell for profit. Some convicts with good conduct were granted the privilege of working all day in their potato fields and sleeping there at night, provided they arranged substitutes for their government-assigned work.

The prisoners' main tasks included constructing station roads and other tasks for the Commissariat Department. They also significantly contributed to improving station gardens, particularly in the cultivation of potatoes and English vegetables. Additionally, they imparted skills to residents in making cane baskets and chairs. When the jail was closed in 1864, most prisoners received tickets-of-leave, and some were allowed to remain on the hill under certain conditions. In the 1880s, only four Chinese resided on the hill, with one of them maintaining a productive garden.

Education Hub

According to the Gazetteer (1885), by the early 1800s, there were a total of 248 government schools in the district. Among them, one was a high school offering instruction in English and Sanskrit up to the matriculation standard, while four were Anglo-Vernacular schools teaching in both English and Marathi. The remaining 243 schools were vernacular schools, consisting of 238 boys' schools and five girls' schools.