Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Paleolithic Sites at Malvan

- Microlithic Tools at Koloshi Village

- The Petroglyphs of Sindhudurg

- Association with the Pandavas and their Exile

- Early Empires & Political Transitions

- Revatidvipa (Redi) and Chalukya Naval Expansion

- Shilahara Rule and Jain Traditions at Pendur

- Kadamba Turmoil and Migration from Goa to Kudal

- Yadava Control and the Deshmukhs of Kudal

- Medieval Period

- Vijayanagar Empire

- Bahmanis and the Adil Shahis of Bijapur

- The Rajas of Sawant and Sawantwadi

- Sindhudurg as the Jal Rajdhani of Shivaji’s State

- Mughal Incursions and Regional Instability

- Naval Command under Kanhoji Angre in Sindhudurg

- Arrival of the Dutch in Vengurla

- Kolhapur Marathas and British Intervention in Malvan

- Colonial Period

- Malvan in the Colonial Administrative Framework

- Port Divisions and the Southern Maritime Network

- Trade Volumes and Commodities of the Malvan Division

- Devgad Alphonso

- Vijaydurg Division

- Amboli

- Struggle for Independence

- Quit India Movement

- Post-Independence

- Sources

SINDHUDURG

History

Last updated on 18 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Sindhudurg district, located at the southernmost tip of the Konkan coast, has a long and rich history. Today, it is commonly known for its role as a coastal stronghold; however, what many might not know is that its past stretches back to prehistoric times. Archaeological evidence, including stone tools, indicates human presence here during the Palaeolithic period, one of the earliest phases of human activity on the Indian subcontinent.

In the centuries that followed, parts of the region came under the influence of large South Indian kingdoms, such as the Vijayanagara Empire. By the 17th century, it had come under Maratha rule, with inland areas governed by local chiefs (most notably the Sawants, who ruled from the town of Sawantwadi). During the colonial period, the British recognised Sawantwadi as a princely state, while coastal areas saw limited involvement by Portuguese, Dutch, and British trading companies. Under British administration, the entire region was incorporated into Ratnagiri district as part of the Bombay Presidency. In 1981, Sindhudurg was established as a separate district through the reorganisation of southern Ratnagiri, with its headquarters at Oros.

Etymology

The name Sindhudurg is derived from the prominent fort located in Malvan taluka of the district (which will be discussed more below). It is generally believed that the term Sindhudurg is a combination of two Marathi words: Sindhu and Durg. In Marathi, Sindhu typically refers to the ocean or sea, while Durg translates to fort. Therefore, Sindhudurg can be understood to mean ‘fort in the sea’ or ‘fort facing the ocean’.

Ancient Period

Paleolithic Sites at Malvan

One of the earliest traces of human presence in Sindhudurg district comes from areas around Malvan, where stone tools linked to the Lower and Middle Paleolithic periods have been found. These terms refer to the early part of the Stone Age (long before farming began) when small groups of humans lived by hunting and gathering, and made tools by striking flakes from stone.

In the 1970s, archaeologist Statira Guzder recorded tools at several sites in Malvan taluka, including villages like Salel, Haddi, Tondvli, Kandalgon, and Sarjekot. A more recent site at Karlacha Vhal, located on the slope of a ferricrete plateau (a hard, iron-rich surface typical of the region), yielded over 140 tools. These were made from materials like quartz, quartzite, and sandstone, shaped into sharp flakes and pointed tools. Most were found on the surface, lying in clusters among weathered stone, suggesting that this location may have been repeatedly used for tool-making or food processing.

Microlithic Tools at Koloshi Village

Further inland, near Koloshi village in Kankavli taluka, another group of stone tools was found in 2019. Here, researchers identified a small rock cave while surveying nearby areas. Excavations inside the cave have notably revealed a range of stone tools, including microliths, blades, and larger flaked implements. The microliths (small, flaked tools typically associated with the Mesolithic period) were made from fine-grained stone and show evidence of shaping through pressure flaking.

Preliminary analysis suggests that some of the microliths are about 10,000 years old, while the larger tools may be significantly older, possibly up to 40,000 years or even more. Further testing is ongoing, including residue analysis, which may help determine how the tools were used and provide a glimpse into the life of early humans during this time.

The Petroglyphs of Sindhudurg

Another significant trace of the district’s past comes from its petroglyphs, which are prehistoric rock carvings that are etched into the laterite surfaces of the Konkan plateau. These carvings were created by chiselling directly into the rock or, in some cases, by arranging stone fragments into recognisable forms. The petroglyphs found in Sindhudurg district are attributed to the Mesolithic and early Neolithic periods, with a general date range estimated between 10,000 and 4,000 BCE. While petroglyphs have been recorded in various parts of India, the Konkan region holds one of the highest known concentrations. Within this belt, Sindhudurg and Ratnagiri stand out for the number and variety of sites.

The systematic documentation of these carvings in Sindhudurg began in 2002, when a team led by Mr. Satish recorded more than sixty petroglyphs across two villages in the district. Subsequent surveys expanded the total number to over one hundred and forty, distributed across multiple lateritic plateaus. The carvings were found chiefly in the talukas of Malvan, Kudal, and Vengurla.

The largest concentration of rock art in the district is found at Kudopi village (Malvan taluka), where approximately eighty figures are arranged in three clusters across the surface of a single plateau. The carvings vary in scale and technique. Subjects include faunal forms such as humped cattle, deer, and boar; geometric motifs including triangles, circles, spirals, and rectangles; and a number of anthropomorphic figures, some of which appear in grouped or narrative-like compositions.

The discovery of petroglyphs in the Konkan region is considered highly significant, as it marks the earliest archaeological record of prehistoric activity along the western coastal belt of Maharashtra. Today, the petroglyph sites of Sindhurdurg are included in UNESCO’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites. Their age, scale, and the questions they raise about early life in the region continue to draw interest from researchers and conservationists alike.

Interestingly, while the carvings were not formally studied until the early 21st century, many of the carvings had been known to local residents for a long time. In village usage, they were commonly referred to as Pandava chitra, which literally means “drawings of the Pandavas.” This term, in many ways, indicates a long-standing local awareness of the carvings as ancient or ancestral in character.

Association with the Pandavas and their Exile

Notably, mentions of the Pandavas in the above context are not incidental in the district. Across the Konkan region, the Pandavas are more frequently invoked in local tradition than other epic figures, and their names are often used to signify antiquity. Many local traditions in the Konkan region speak of connections with the heroes of the Mahabharat, particularly the Pandavas. In several parts of Sindhudurg, the five brothers are believed to have travelled through the coastal hills and villages during their exile.

These accounts, passed down through generations, often describe their presence as being received with honour by the local population. Some versions refer to a ruler named Raja Veerat Ray, who is said to have welcomed the Pandavas and later supported them during the war at Kurukshetra. Such traditions remain part of the oral history of the region and are linked to place names, carved figures, and yatra customs.

Early Empires & Political Transitions

The territory that now forms Sindhudurg district has, at various times, fallen under the authority of different kingdoms. Little is known about its early history, however, available archaeological findings and a few literary references allow for a general outline, particularly when considered in relation to the broader histories of Konkan and the Deccan region (the cultural and political spheres to which Sindhudurg has historically belonged).

The earliest discernible phase of political control appears to coincide with the ascendancy of the Satavahana dynasty, which ruled large portions of the Deccan from approximately the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE. Although no direct inscriptions of Satavahana rulers have been found within the present boundaries of the district yet, the broader cultural and political currents of the period likely extended to this coastal region.

In the neighbouring Ratnagiri district, several ancient rock-cut caves, such as those at Kol and Chiplun, have been dated to this era (see Ratnagiri for more). These caves are generally understood to be Buddhist in character, created as monastic dwellings and meditation halls. While it cannot be definitively said that they were commissioned by the Satavahanas themselves, their development coincided with the period of Satavahana rule, when Buddhism received considerable patronage in many parts of western and southern India.

It is important to note that by the 2nd century BCE, it appears that Ratnagiri had begun to draw the attention of traders, monks, and maritime travelers. Dabhol was prosperous in the ancient times. Ratnagiri district was a prominent trade center during this time, so much so that it is believed that the well-known maritime text, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE), refers to one of these ports. The adjoining region of Goa, which borders the southern part of Sindhudurg, was likewise prominent when it came to trade and commerce. These developments likely had spillover effects into the Sindhudurg region, due to its geographic proximity, and perhaps influenced both its trade and religious life.

Following the decline of the Satavahanas, parts of coastal Konkan, including Sindhudurg, appear to have come under the influence of the Western Kshatrapas, particularly under the reign of Rudradaman I (c. 130–150 CE). His dominion extended over Gujarat, Malwa, and parts of Konkan.

By the early 6th century CE, a local dynasty known as the Mauryas of Konkan had emerged as rulers of the northern and central Konkan coast. Their authority extended over several coastal settlements, and one of their principal strongholds was Revatidvipa, which is generally identified by scholars to be the present-day town of Redi in Sindhudurg district.

Revatidvipa (Redi) and Chalukya Naval Expansion

Notably, one of the most significant episodes in the early history of Sindhudurg centres around this fortified coastal settlement. Its prominence as a fortified outpost on the Arabian Sea drew the attention of rising powers in the Deccan region of the time.

In the latter half of the 6th century, Kirtivarman I of the Early Chalukya dynasty (r. c. 566–598 CE) launched a series of campaigns across the Deccan. His victory over the Mauryas is recorded in the Aihole inscription, where they are listed among other defeated lineages such as the Nalas and Kadambas. Notably, the primary objective of this expedition appears to have been the capture of Revatidvīpa itself.

Notably, many historians have observed that Kirtivarman’s successful occupation of Revatidvīpa would not have been possible without a coordinated naval strategy and it stands as one of the earliest references to maritime campaigning in the early Deccan. Following the conquest, authority over the region was entrusted to a Chalukya noble named Swamiraja, who is reputed to have led eighteen successful battles and possibly appointed as governor of the former Maurya territory. His headquarters were established at Revatidvipa, from where he appears to have exercised local control for a brief period.

The peace did not last. During the reign of Mangalesha, Kirtivarman’s younger brother and successor (r. c. 597–610 CE), Swamiraja is said to have allied himself with Buddharaja, the Kalachuri ruler of Mahishmati. This alliance took place at a time when the Chalukyas were engaged in northern expansion. It is said that, upon hearing this, Mangalesha was forced to abandon his planned campaign and turn back south. Marching upon Revatidvipa, he then defeated and deposed Swamiraja.

Following its capture, Redi was placed under the charge of a Chalukya vassal named Indravarman from the Batpura lineage, who was a maternal relative of Mangalesha. His position is attested by a copper-plate inscription issued from Revatidvipa in 610 CE, which provides one of the earliest epigraphic evidences of direct Chalukya administrative presence within the present-day limits of Sindhudurg district.

Shilahara Rule and Jain Traditions at Pendur

By the 10th century CE, large parts of the southern Konkan, including what is now Sindhudurg district, had passed under the authority of the Shilaharas of South Konkan, who were a regional branch of the dynasty. Interestingly, it is said that they established their capital at Vallipattana, a name now identified with Kharepatan village, which lies in the present-day district. From this inland seat of power, the Shilaharas exerted control over much of the coastal tract and patronised both Hindu and Jain institutions. Many traces of their presence survive even today and remain scattered across the district.

Fascinatingly, one of the most important archaeological sites tied to this period is located at Pendur, a village in Malvan taluka. In 2011, an archaeological team led by Dr. Sachin Joshi of Deccan College uncovered the remains of a large platform and several carved stone images near the Sateri Devi Mandir. These included Jain icons, such as those of Mahaveer and Kubera, alongside Hindu figures like Matrika and Mahishasura Mardini.

The presence of Jain imagery in Sindhudurg is noted by scholars to be highly significant, as before these findings, medieval Jain activity in much of the region was sparsely documented. Oral traditions and stylistic assessments suggest that the temple complex may date to the 10th–12th centuries CE, with possible connections to King Gandaraditya of Kolhapur, who was a known patron of Jainism.

Another trace of the dynasty’s architectural legacy is found further north at Vijaydurg, a coastal fort which guards the mouth of the Vaghotan River and lies between the present-day Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg districts. It is believed that the site was originally constructed between 1196 and 1206 CE by Raja Bhoja II of the Shilahara dynasty. It went on to become a major stronghold in later centuries, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Kadamba Turmoil and Migration from Goa to Kudal

Around the same period, the inland town of Kudal witnessed a wave of migration from neighbouring Goa, spurred by political upheaval under the newly established Kadamba dynasty. A stone inscription from Kurdi (in present-day Sanguem taluka, Goa), dated to around 960 CE, records that Kantakacharya, founder of the Kadamba line in Goa, was granted territory by the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani following their victory over the Rashtrakutas.

Subsequent Konkani literary traditions, particularly those preserved by Varde Valaulikar (Shennoi Goembab), recount that certain Goan families fled Kantakacharya’s rule around 980 CE, due to political or religious persecution. Some among these migrants are said to have settled in Kudal and neighbouring villages, where they integrated into local society as pujaris, temple stewards, and financial officials. In due course, they rose to prominence in the courts of Shilahara rulers in Thane and Kolhapur.

Yadava Control and the Deshmukhs of Kudal

By the close of the twelfth century, the Konkan coast, including the tract that forms present-day Sindhudurg, had come under the growing influence of the Yadava kings of Devagiri. Though direct records from the region during this time remain limited, the period marks the emergence of one of the most enduring local families in the district’s history who went on to become the Deshmukhs of Kudal.

Often referred to as the Kudal Deshkars, they are believed to have first held positions of local administration as Brahmin feudatories under the Yadavas and other ruling houses. From these beginnings, they steadily rose in prominence, extending their influence over both inland and coastal areas of southern Konkan. The family’s hold over Kudal grew firmer in the centuries to follow, and they continued to play a key role in the politics of the region during the Bahmani and Maratha periods (will be discussed below).

Medieval Period

From the 11th century onwards the tract now forming Sindhudurg district was ruled by a succession of many dynasties and local powers. Remarkably, it is noted that the town of Kudal during the early years, was the seat of the Kudal Deshkar Brahmins, hereditary chiefs who held their lands under the Kadambas of Goa and later the Yadavas of Devagiri. During the Kadamba period, it is said that the area was likely known as Naushe Iridige.

The position of Kudal on the river routes from the Ghats to the Arabian Sea gave it both commercial and military value. Under the Yadavas, whose power reached its height in the late thirteenth century, these routes were guarded by a network of forts and watch posts.

The Delhi Sultanate under Alauddin Khilji pushed into the Deccan in the early fourteenth century, but its hold on the South Konkan appears to have been slight. The hill barrier of the Ghats and the rugged coast likely made permanent occupation difficult, and control was asserted more by periodic expeditions than by settled rule.

Vijayanagar Empire

It was around this time that a new political power also emerged in the south. In 1336 CE, Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, two brothers who had once served the Kakatiya dynasty of Warangal (present-day Telangana), are said to have regrouped after the collapse of their patrons and founded what would become the Vijayanagara Kingdom. Breaking away from the Delhi Sultanate’s hold, they established their capital on the banks of the Tungabhadra River (Karnataka) at Hampi, from where the empire expanded rapidly and became one of the most formidable powers in southern India.

At its peak, the Empire controlled or influenced vast swathes of the peninsula: Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Goa, and parts of Telangana and Maharashtra, including areas close to the South Konkan coast. Sindhudurg, though far from the capital, seems to have fallen within its extended political orbit. A short but intriguing note in the colonial district Gazetteer (1880) points to this connection. Writing about the late 14th century, the Gazetteer records that in 1391 CE, “Vadi [likely referencing the present-day Sawantwadi] was under an officer of the Vijayanagar dynasty, whose headquarters were at Goa.” Though the record is brief, it suggests that this part of the South Konkan coast may have been governed through local officers or hereditary administrators aligned with the larger power to the south.

Some traces of that connection still linger in the landscape. In Malvan Taluka, local tradition credits the construction of Dhamapur Lake, a large man-made reservoir nestled between low wooded ridges, to this period. Built, according to oral history, in 1530 CE by a figure named Nagesh Desai, the lake remains in use to this day. Desai is remembered as a Mandlik, a kind of regional administrator, linked to the Vijayanagara system of delegated authority.

Nearby stands the Bhagwati Mandir, considered one of the oldest surviving mandirs in the district. Like the lake, the shrine is associated with Nagesh Desai and is believed to date to around the same time, circa 1530 CE. The Mandir is dedicated to Bhagwati Devi and continues to be a place of active worship even today.

Bahmanis and the Adil Shahis of Bijapur

Even as Vijayanagara extended its reach along the southern Konkan, another power was gathering strength in the Deccan plateau. In 1347 CE, Zafar Khan, a former officer of the Delhi Sultanate, declared independence and founded the Bahmani Sultanate, with its early capital at Gulbarga (present-day Kalaburagi, Karnataka). Over time, the Bahmanis laid claim to much of the western coast, including the South Konkan, though their presence in this region was mostly indirect, as they administered through governors based in Goa or Belgaum rather than permanent military occupation.

By the 1470s, Kudal had passed from the control of its earlier Deshkar Brahmin chiefs into the hands of the Bahmani state.

However, the Bahmani state weakened after the death of its minister Mahmud Gawan in 1481, and by 1490 it had splintered into five successor states. In that division, the Adil Shahis of Bijapur inherited the western coastal tract, including much of present-day Sindhudurg. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1880), “on the establishment of their power at the close of the fifteenth century, [Sawantwadi] became part of the territory of the Bijapur kings.” Under Adil Shahi rule, local strongholds, including those at Kudal, are noted to have been repaired or modified.

The Rajas of Sawant and Sawantwadi

Interestingly, it was during the time of the Adil Shahis that the Sawant family, who would later become the ruling house of the Sawantwadi princely state, began to assert themselves. According to regional tradition, Mang Sawant, the founder of the line, had originally come to the coast with a Vijayanagara force. After the collapse of that kingdom following the Battle of Talikota in 1565, he established himself independently at Hodawade (in present-day Karnataka), a stronghold near the trade and military routes connecting the Konkan to the Deccan plateau.

The Gazetteer (1880) mentions that Mang Sawant was first based at Gandharvagad (now in Chandgad taluka, Kolhapur district), where he was known by the title Chandgudhadhipati. From there, he shifted south to Hodawade, where he is said to have defeated local rajas who had previously controlled the region. As his position strengthened, his name gained recognition across the coastal belt.

One of his principal rivals was the Raja of Kudaldesha, whose territory likely included parts of modern Kudal Taluka. Both the Sawants and the Kudal Deshkars were nominal vassals of the Bijapur Sultanate, however, it is important to note that their political loyalties during this period were rarely stable. Alliances in the Konkan shifted frequently, later between Bijapur, the Mughals, the rising Maratha powers, and the Portuguese—depending on who held advantage in the region at any given time.

In 1580 CE, Mang Sawant, along with Dev Dalvi, a general aligned with the Kudaldeshastha side, launched a joint campaign to take control of the Kudal region. The local raja appealed to Bijapur for assistance, and a conflict ensued near the fortified hills of Manohar and Mansantosh, not far from Hodawade. In the battle that followed, Mang Sawant was killed. Though he did not survive the campaign, the family he founded continued to shape the fortunes of the South Konkan for generations to come

Sindhudurg as the Jal Rajdhani of Shivaji’s State

By the middle of the seventeenth century the South Konkan lay within reach of the rising Maratha power under Shivaji Bhosale. His early campaigns against Bijapur brought him to the Konkan coast, where control of the harbours and passes became essential to his wider designs in the Deccan region.

One of the first coastal towns to come under Maratha influence was Kudal, captured around 1659–1660. Although briefly lost again to Bijapur, it was retaken by 1664, and soon after, Shivaji reorganised the area into a new administrative unit made up of Kudal and over 200 villages. Local chiefs were retained in power; for instance, in 1671, the chief of Kudal, Narhari Anandrao, was ordered to collect tax on salt from Bardesh (Goa), a sign that the region had been absorbed into the fiscal system of the Swarajya.

Shivaji’s interest in the coast, it is said, intensified after a failed attempt to capture the island fort of Janjira (which lies in Alibag, Raigad district, Maharshtra) from the Siddis. In 1665, after the siege failed, Shivaji began looking for an alternative naval base on the west coast. He chose Malvan, a small natural harbour shielded by rocky outcrops and shallow reefs, difficult for large enemy ships to approach. Between 1664 and 1667, on a rocky islet just off Malvan, Sindhudurg Fort was built.

As mentioned earlier, the name Sindhudurg is believed to derive from two Marathi words: Sindhu (sea) and Durg (fort), meaning "fort in the sea" or "fort facing the ocean." True to its name, the fort was built by Chhatrapati Shivaji to guard the western coastline of his kingdom and establish a naval stronghold.

The construction of Sindhudurg Fort was a significant engineering feat. Very notably, it is said that approximately 3,000 workers contributed to its construction. The fort spans 48 acres, with fortified walls that stand 29 ft. high and 12 ft. thick. These walls extend over two miles and are protected by 52 bastions. Some of these bastions feature secret exits, and many include embrasures designed for mounting cannons.

Interestingly, it is believed that Shivaji was very pleased with the fort’s construction and at the request of the fort’s architect, a handprint and footprint of the Maratha king are embedded on a slab within the fort.

Uniquely, the fort is also home to the Shivrajeshwar Mandir, which is regarded as the only Mandir dedicated to Shivaji Maharaj within a fort.

In parallel with the construction of Sindhudurg, Shivaji expanded fortifications further north and south along the coast. One of the most significant of these was Vijaydurg, which was located at the tip of the Devgad peninsula. Originally known as Gheria, the fort was expanded under Shivaji and later renamed Vijaydurg or the "Fort of Victory." Its strategic positioning (surrounded by the Arabian Sea on three sides and overlooking the Waghotan Creek) made it nearly impregnable. Vijaydurg would later become the principal base for Kanhoji Angre, the Maratha navy’s most prominent admiral. Its prominence in Maratha naval history earned it the nickname "Eastern Gibraltar" in British records.

Around Sindhudurg, Shivaji also constructed a network of subsidiary forts, namely Padmadurg on a neighbouring island, and Rajkot and Sarjekot on the mainland, to secure the harbour approaches and reinforce coastal control.

Together, these forts formed the backbone of Shivaji’s coastal defence system. They allowed the Marathas to challenge Portuguese, Siddi, and European naval presence along the Konkan, and served as staging grounds for campaigns inland and at sea. Sindhudurg, in particular, became known as the jal rajdhani, or rather an important maritime centre of the Maratha state throughout the latter half of the seventeenth century.

Mughal Incursions and Regional Instability

After the death of Shivaji Maharaj in 1680, the region entered a period of instability. His successor, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj, was soon confronted by the advancing Mughal Empire, which under Emperor Aurangzeb intensified its military campaign in the Deccan. As part of this southern offensive, Mughal forces under Prince Shah Alam advanced into the South Konkan in 1683. During this time, notably, the town of Kudal, a key administrative centre in the district, was sacked and set ablaze.

Although Maratha forces regained Kudal the following year, control over the region remained precarious. Local chiefs such as the Sawants of Sawantwadi and the Desais of Kudaldesh are said to have oscillated between supporting the Mughals and the Marathas, depending on the prevailing balance of power. The strategic forts at Kudal and Rajkot were repeatedly contested throughout the 1690s, with each transfer of control likely damaging the fortifications and destabilising the surrounding areas.

By the early 1700s, the Mughal Empire’s capacity to maintain pressure in the Konkan had diminished, and the Marathas re-established effective control over most of the coastal tracts of Sindhudurg. This period marked a return to relative stability, and the reassertion of Maratha naval and administrative authority along the coast.

Naval Command under Kanhoji Angre in Sindhudurg

In the early 18th century, the coastal forts of Sindhudurg district, first developed under Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, came under the control of Kanhoji Angre, the Maratha navy’s most formidable commander. Angre rose through regional service and was appointed Sarkhel (admiral) of the Maratha fleet. From this position, he assumed responsibility for maritime security along the western coastline, particularly across the waters and fortresses of Sindhudurg.

From his main base at Vijaydurg (now part of Devgad taluka), Angre oversaw a network of forts, including Sindhudurg, which retained its stature as the main operational centre of Maratha naval power. From these strongholds, Angre maintained a tight grip on the Konkan’s maritime routes. Merchant ships (whether Portuguese, English, or Dutch) were routinely intercepted off the coast of Sindhudurg and compelled to pay chauth (protection levy) to proceed. This not only enriched the state treasury but also reinforced coastal sovereignty in a period when European powers sought to dominate the Arabian Sea.

Multiple attempts were made by European forces to breach this control. Between 1717 and 1720, Anglo-Portuguese expeditions were launched to capture Angre’s bases. Yet the natural defences of Sindhudurg Fort, combined with Angre’s knowledge of local tides, reefs, and anchorages, allowed the Maratha fleet to consistently frustrate larger, better-armed European vessels.

During this time, Devgad Fort, constructed under Angre’s command in 1705, emerged as a secondary watchpost within the district, guarding northern sea approaches to Sindhudurg and serving as a customs station for vessels arriving from Janjira and further south. Harbours at Malvan and Vengurla were also used for minor ship repairs, provisioning, and revenue collection.

Arrival of the Dutch in Vengurla

By this time, the decline of Mughal authority in the Konkan had also opened the coast to competing powers. Chief among these were the Sawants of Sawantwadi, the Portuguese in Goa, and new European entrants. The harbour of Vengurla, lying within easy reach of the frontier and possessing a sheltered anchorage, became a point of particular importance. Its position gave access both to the coastal trade and to the inland passes leading to the Deccan.

In 1665, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established a base at Vengurla, perhaps drawn by these advantages. The harbour offered a platform from which to challenge Portuguese dominance in nearby Goa, while the surrounding hinterland supplied commodities: cloth, millets, cardamom, and salt, that could be readily traded across the Indian Ocean. The Dutch built a warehouse (wakhar) and other facilities to support their operations, and for some years, the port served as their northern outpost on the Konkan coast.

Remains of the Dutch period, notably the old warehouse, survive as a reminder of the port’s earlier commercial connections and the centuries of contest that shaped its fortunes.

Kolhapur Marathas and British Intervention in Malvan

Alongside Vengurla, the coastal town of Malvan emerged as one of the most contested sites in Sindhudurg district during the 18th century. Of all the ports along the southern Konkan, Malvan appears to have been one of the most coveted. Its deep and sheltered harbour, guarded by the offshore stronghold of Sindhudurg Fort, offered year-round anchorage and direct access to both regional and international maritime routes. The town’s position allowed for the collection of customs, deployment of naval patrols, and effective control over trade and supply lines along the western seaboard.

According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1880), Malvan and its adjoining forts were initially under the Sawants, who maintained a naval presence in the area through much of the early 18th century. However, by the 1760s, the Kolhapur branch of the Maratha Confederacy (or rather the Kolhapur State), had begun to assert claims over the same coastline. The Sawants held Redi, Nivti, and Vengurla, while Kolhapur’s forces made repeated attempts to seize Malvan and its harbour.

As open hostilities escalated between the two factions, the British East India Company, well-established in Bombay, worried, moved to secure their trade routes along the coast. In 1765, a Company-led expedition under Major Gordon and Captain Watson captured Sindhudurg Fort and Redi Fort. The British briefly renamed Malvan as “Fort Augustus.”

However, the cost of maintaining control over Malvan proved burdensome. The Gazetteer notes that for the British, the fort was “unprofitable and very hard to dismantle.” In 1766, just one year after its capture, Malvan was returned to the Kolhapur Raja under strict terms:

- The Raja was required to guarantee that trade would not be obstructed;

- He was to pay a sum of ₹3,82,890 (equivalent to £38,289 at the time) to the Bombay Government;

- And he was to allow the Company to establish a factory (trading post) at Malvan.

Simultaneously, Redi Fort was returned to Khem Sawant, provided he pays ₹2,00,000 (about £20,000). This amount was to be raised through a 13-year mortgage on the revenues of Vengurla, which remained under Sawant control. To enforce the agreement, it is noted that the British took two hostages from the village of Wadi, established a factory at Vengurla, and raised the British flag over the port.

Despite these treaties, tensions resurfaced. By 1780, relations with the Sawants had broken down. The hostages had escaped, the Sawants refused to honour revenue obligations, and the Company, in turn, denied their demand for territorial restoration. In retaliation, Sawant forces launched a surprise assault on Vengurla Fort on 4 June 1780, and retook the port by force, re-establishing control over what they viewed as their rightful domain.

For the next three decades, a fragile equilibrium held:

- Vengurla remained under Sawantwadi;

- Malvan remained under Kolhapur;

- And the British maintained trading rights but no direct control.

This balance ended in 1812, when the British accused the Raja of Kolhapur of failing to suppress piracy along the coast. Invoking a clause in their treaty with the Peshwa, the British demanded and secured the formal cession of Malvan. From that point onward, Malvan and Vengurla were placed under direct Company administration, marking the end of independent regional control over the Konkan’s southern coast.

In the following years, both towns were gradually developed under British rule. Malvan retained its status as a naval and administrative centre, anchored by Sindhudurg Fort, which remained in use. Vengurla, on the other hand, was developed as a municipal town, with roads, marketplaces, public buildings, and a hospital constructed in subsequent decades.

Colonial Period

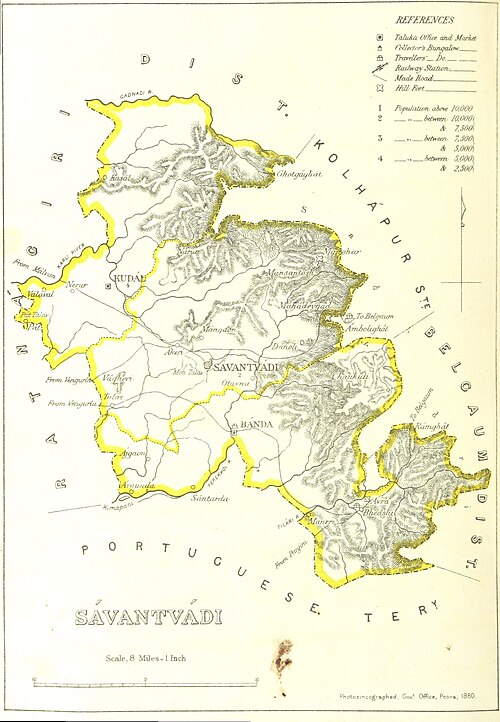

With the expansion of British control in the early nineteenth century, the region now forming Sindhudurg district was administered as part of Ratnagiri. The administrative structure was gradually formalised over the decades. In 1832, Ratnagiri was designated a full district comprising five subdivisions. By 1868, the district was expanded to include eight subdivisions, namely, Dapoli, Chiplun, Guhagar, Sangameshwar, Ratnagiri, Rajapur, Devgad, and Malvan. It also had four petty divisions under the jurisdiction of magistrates’ courts at Mandangad, Khed, Lanja, and Vengurla. Of these, Devgad, Malvan, and Vengurle now fall within the boundaries of Sindhudurg district.

In the case of Sawantwadi (which, as mentioned earlier, was ruled by the Sawants), the course of political change followed a distinct path. As it was ruled by the Sawant dynasty, this territory retained a measure of autonomy well into the 19th century. British involvement intensified following the events of 1765 (as noted earlier), when pressures along the southern frontier grew more acute. By 1838, citing misgovernment and internal disorder, the British formally brought Sawantwadi under their protection. It was thereafter recognised as a princely state within the framework of British India. While the Sawant rulers continued to hold nominal authority, a British political superintendent was installed to supervise affairs, and the local military force, styled the Sawantwadi Local Corps, was placed under the command of British officers, though financed by the state treasury.

Malvan in the Colonial Administrative Framework

With the formal establishment of British authority in this part of the Konkan region, the administrative structure of the region underwent steady reorganisation. Among the southern ports of the erstwhile Ratnagiri district, Malvan emerged as a site of growing importance owing to its deep natural harbour, longstanding mercantile activity, and proximity to the fortified island of Sindhudurg.

The colonial District Gazetteer (1880) records that Malvan was one of only three locations in the broader district to house an official bungalow for district officers, the others being Harnai (now in Ratnagiri) and Vagothan (now part of Raigad). This presence of colonial infrastructure suggests that Malvan may have functioned as a subordinate administrative centre during the later 19th century, where matters of revenue and coastal policing functions were being overseen in the southern Konkan.

Port Divisions and the Southern Maritime Network

During the colonial period, the maritime infrastructure of the district was subsumed into the larger customs framework of British Ratnagiri. Fourteen ports were formally recorded, grouped into six customs divisions: Suvarnadurg, Anjanvel, Ratnagiri, Vijaydurg, Vengurla, and Malvan. Of these, the latter two divisions, Malvan and Vijaydurg, fall within the present-day Sindhudurg district. Their inclusion in the structured customs regime, in many ways, highlights the historical significance of the district's ports within the broader commercial geography of the Konkan region.

Trade Volumes and Commodities of the Malvan Division

Malvan, along with Devgad and Achra, was listed in the Gazetteer (1880) as a principal port within its division. The trade handled through these outlets primarily comprised agricultural and food commodities, suggesting that the region served both as a supplier and a transit point in western India's food grain economy.

As per figures from the Gazetteer (1880), the Malvan division recorded a total trade of £88,574 in the year 1878–79. Of this, £46,869 comprised imports and £41,705 exports. Compared figures with trade totals from earlier years showed the following:

- 1874-75: £77,683

- 1873: £81,639

- 1871: £81,154

- 1867: £99,619

- 1850: £43,274

- 1840: £10,775

This data illustrates fluctuations in trade volumes over time in the Malvan division, showing variations in both import and export values across different years.

Each of the ports within the Malvan division maintained distinct export and import profiles, based on their local geography and agricultural production:

- Devgad port: The primary exports from Devgad included hemp, betel leaves, betel nuts, sugarcane, fuel, and bamboo, all of which were mainly sent to the British Bombay (now Mumbai City). Additionally, Devgad exported hemp, fish, and blankets to other ports in the Konkan region. The imports into Devgad include husked and cleaned rice, nagli, vari, harik, groundnuts, tiles, fish, timber, blankets, coconuts, oil, molasses, tobacco, chillies, cocoa kernels, salt, and country piece goods from other ports within the Konkan region.

- Achra Port:The port of Achra (now a small village) was involved in both exports and imports. Exports to Bombay (now Mumbai City) included hemp, coir, sugarcane, earthen pots, fuel, husked and cleaned rice, and hardware. To other Konkan ports, Achra sent rice, grains, pulses, nuts, spices, oils, timber, salted fish, coconuts, betel nuts, and handicrafts. Imports consisted of rice and hardware from Bombay (now Mumbai City), alongside similar agricultural products and general goods from other Konkan harbours.

- Malvan Port: The port of Malvan primarily exported a variety of goods to Bombay, including rice, linseed, gallnuts, hemp, cashew nuts, dried rinds of Kokam (Garcinia purpurea), coir, coir ropes, coconuts, chilies, and sugar. Imports from Bombay (now Mumbai City) included rice, wheat, gram, oil, hardware, and English piece-goods. Malvan also maintained extensive inter-port and coastal trade: pulses, molasses, coconuts, salt, sugar, betel nuts, oil, hemp seed, onions, cashew nuts, palm leaves, and tiles to other Konkan ports; cashew nuts and coconuts to Honavar (Karnataka); rice, clarified butter, and earthen pots to Cochin (now Kochi, Kerala); onions to Kundapur (Karnataka); rice, millet, sesame, pulses, and onions to Cannanore (now Kannur, Kerala); rice and pulses to Kalilat (location uncertain, possibly in present-day Kerala or Lakshadweep); and rice, molasses, pigs, and oil to Goa. This network hints at Malvan’s role as a central exchange hub between Bombay (now Mumbai City), the Konkan, and distant ports along the Arabian Sea.

Devgad Alphonso

Beyond its harbour, Malvan Division was also linked to the cultivation and trade of the celebrated Devgad Alphonso mango. Though nearby Ratnagiri Alphonso often attracted greater renown, the orchards of Devgad taluka produced a fruit prized for its rich aroma, fibreless pulp, and deep golden hue. Local tradition holds that grafts from Ratnagiri were first brought here in the early 19th century, leading to the development of a distinct sub-variety adapted to Devgad’s coastal soils and microclimate.

By the late colonial period, these mangoes were already appearing in Bombay markets, shipped seasonally from Devgad port alongside other agricultural produce. Today, the Devgad Alphonso enjoys Geographical Indication (GI) status and is marketed worldwide. The harvesting season typically runs from February to early June, with the short supply period adding to its value.

Vijaydurg Division

Alongside Malvan, Vijaydurg was another of the six division ports during the colonial period. It remains a significant port even today, operating as a minor (non-major) port under the jurisdiction of the Maharashtra Maritime Board (MMB). By the late 19th century, it ranked among the busiest outlets on the Konkan coast.

The colonial district Gazetteer (1880) records that in 1878–79 the division’s total trade amounted to £245,415, of which imports were valued at £107,217 and exports at £136,108. Earlier figures of £234,525 in 1874–75, £251,230 in 1873, and £305,978 in 1871. Compared to Malvan’s figures for the same years, Vijaydurg consistently managed a larger turnover, underscoring its importance within the erstwhile Ratnagiri district’s maritime economy.

- Jayatpura Port: Among Vijaydurg’s satellite harbours, Jayatpura was the most prominent. Its exports ranged from husked and cleaned rice, jvari, and nagli to coriander seed, chillies, coconut products, oils, molasses, and tobacco. Cargoes were sent to ports across the Konkan, to Bombay (now Mumbai City), Goa, Kumta (Karnataka), Baliapatam (now Kannur district, Kerala), Calicut (now Kozhikode, Kerala), Cochin (now Kochi, Kerala), Cutch (now Kutch, Gujarat), Makran (Pakistan), and notably even Muscat (Oman). Imports included agricultural produce, textiles, hardware, coconuts, salted fish, salt, fuel, spices, and cocoa kernels, arriving from other Konkan ports, Bombay (now Mumbai City), Goa, and Calicut. The scale and diversity of this traffic placed Jayatpura in regular contact with both regional markets and overseas destinations.

- Vijaydurg Port: The main harbour at Vijaydurg specialised in exports of gallnuts, molasses, hemp, ambadi, bamboo, shembi bark, and twine, most of which were shipped to Bombay (now Mumbai City). Additional trade included molasses, hemp, and ain bark to other Konkan ports; sugarcane to Goa; husked rice to Cochin; and rice, hemp, and pulses to Calicut. Imports brought in husked and cleaned rice, nagli, vari, millet, wheat, coconuts, cocoa kernels, palm leaves, and piece goods from Konkan ports; piece goods from Bombay (now Mumbai City); salt from Mora (Raigad district, Maharashtra); husked rice from Antora and Talabadi; salted fish from Goa; and coconuts from Kankon (Canacona, Goa). While some consignments were consumed locally, others were forwarded to Kolhapur and the Deccan plateau. Even today, Vijaydurg remains a functioning port, though its trade is now limited to small volumes of foodstuffs.

Amboli

While Vijaydurg and other harbours formed the coastal nodes of trade, their prosperity depended on inland routes connecting the Konkan with the Deccan. Chief among these was the pass through Amboli, a hill settlement that served as the principal staging post on the road from Vengurla port to Belgaum (now Belagavi, Karnataka). During the colonial period, this route carried commercial goods, postal traffic, and military supplies from Sindhudurg’s ports to garrisons in the southern and central Deccan.

Notably, Amboli’s association with the armed forces was not limited to the passage of troops. Many men from the village are believed to have served in the British army during the pre-independence era. The tradition has continued into modern times, and it is common to find households here with at least one member in the Indian Army. Among them was Pandurang Mahadev Gawade, who lost his life on 22 May 2016 while engaging five Lashkar-e-Taiba militants at Drug Mulla, Kupwara district, Jammu & Kashmir. His bravery was recognised with a posthumous award of the Shaurya Chakra on the eve of the 68th Republic Day.

Struggle for Independence

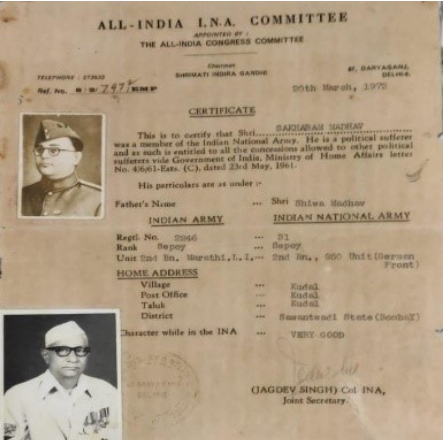

By the early decades of the 20th century, the movement for Indian independence had gathered momentum across the country. In Sindhudurg district, as in other parts of the Konkan, individuals contributed in varied ways — some through organised protest, others by joining revolutionary groups or military units whose loyalties lay with the national cause. Among them was Sakharam Madhav, whose life connected the local history of Kudal to the wider political currents of the time.

Born on 10 August 1910 in Ambadpal (present-day Kudal taluka), Sakharam lost both parents to a plague outbreak when he was four. In 1929, a British recruitment rally at Kudal High School changed the course of his life. Sakharam, then tending buffaloes nearby, joined the drill on a whim and was selected for service. His first posting was at Belgaum (now Belagavi, Karnataka).

During his service in the British army, it is said that Sakharam maintained contact with nationalist circles. Over time, suspicions arose that he was assisting revolutionary movements, and this brought him under close watch by the authorities. Eventually, he was sent back to his village, a move intended to curtail his influence. When the Second World War began in 1939, Sakharam was called back into army service. He was sent to fight in the Eastern Front, in what is now Myanmar (then Burma), an important battleground between British and Japanese forces.

Between 1943 and 1945, Sakharam heard about Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his call to join the Indian National Army (INA): a force that fought alongside Japan against the British, aiming to secure India’s independence. Inspired by Bose’s message, Sakharam decided to support the INA. This led to his arrest and a short time in prison. After being released, he officially joined the INA. He fought in military operations in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and in Myanmar until the end of the war.

Following independence, Sakharam served in the Indian Police until 1965. His contributions to the freedom movement were acknowledged on India’s 25th Independence Day by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and by the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. He died on 21 May 1999 at the age of 90.

Quit India Movement

While individuals such as Sakharam Madhav contributed through personal service and revolutionary activity, the 1940s also saw a surge of mass participation in the struggle for independence. This was most visible during the Quit India Movement of August 1942, when Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress called for the British to leave India immediately.

The appeal resonated across Sindhudurg. Early arrests of senior Congress leaders by the colonial administration, meant to quell the agitation, instead deepened local resentment. In towns and villages, groups organised to resist in whatever ways they could. Some cut post and telegraph wires to disrupt official communication; others targeted government offices.

In Malvan, protesters went further, setting fire to the taluka office and the government treasury. The destruction of records and funds caused losses running into several lakh rupees and stood out as one of the most determined acts of defiance in the district.

Post-Independence

Following Independence in 1947, the territory now comprising Sindhudurg district remained a part of Ratnagiri district under the newly formed Bombay State. The former Sawantwadi State, which had been a princely state under British paramountcy, was merged into Bombay State soon after accession. Administrative control of the area continued under this arrangement until further reorganisation in the decades that followed.

In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act brought several territorial adjustments to Bombay State, incorporating adjacent regions on linguistic grounds. However, agitation for a separate Marathi-speaking state continued to mount. On 1 May 1960, the bilingual Bombay State was formally bifurcated into the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat, with Sindhudurg remaining under Maharashtra’s jurisdiction.

It was not until 1 May 1981 that Sindhudurg was constituted as a separate district, carved out of the southern portion of Ratnagiri. The district took its name from the fort of Sindhudurg, located off the coast of Malvan, constructed in the 17th century by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Upon its formation, Sindhudurg comprised eight talukas: Sawantwadi, Kudal, Vengurla, Malvan, Devgad, Kankavli, Vaibhavwadi, and Dodamarg. The date of establishment, incidentally, coincided with Maharashtra Day (a day where the formation of the State is celebrated).

Sources

Aarefa Johari. 2014. Why the Konkan belt has become a hotspot for archaeologists. Scroll. https://scroll.in/article/663057/why-the-kon…

Akiyala Imchen, Niharika Srivastava, Suman Pandey, Sushama G. Deo. 2019. Re-investigating Palaeolithic Sites Around Malvan, Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra. Vol 79, Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute.https://www.jstor.org/stable/48652398

Amitabha Gupta. 2022. Vijaydurg Fort is a sentinel with stories of Maratha warfare and resilience. The Telegraph.https://www.telegraphindia.com/my-kolkata/pl…

Asia Mumbai Circle. 2013. List of the protected monuments of Mumbai Circle district-wise. https://web.archive.org/web/20130606093840/h…

BBC. 2022. Maharashtra: Ancient stone age tools found in India cave. BBC.https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-62…

Census Organization of India. 2011. Malwan Town Population Census 2011 - 2025. http://www.census2011.co.in/data/town/802878…

Devgad Mango. n.d. About Us. Devgad Mango.https://devgadmango.com/about-us/

District Administration, Sindhudurg. n.d. History of Sindhudurg District. District Administration, Sindhudurg. https://sindhudurg.nic.in/en/about_district/…

Durg Bharari. n.d. Kudal.https://durgbharari.in/kudal/

Durga Prasad Dikshit. 1980. Political History of the Chālukyas of Badami. Abhinav Publications, New Delhi. https://books.google.co.in/books?id=lEB11tKm…

ET Online. 2019. Murud-Janjira & Padmadurg Fort: Keepers of the Konkan coast. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazin…

Express News Service. 2022. Petroglyph found in Konkan added in UNESCO heritage sites tentative list. Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mum…

Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. 1880. Ratnagiri and Savantvadi. Government Central Press.

Maharashtra State Gazetteer. n.d. History, Chapter 3: Successors of the Satavahanas in Maharashtra. Directorate of Government Printing, Mumbai. https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

N.T. Monc; P.M. Joshi; P. Setu Madhava Rao; S.G. Panandikar; S.L. Karandikar; S.M. Katrc; V.V. Mirashi. 1962. The Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Ratnagiri District. Government Printing, Stationery and Publications, Mumbai.

Neha Madaan. 2011. Deccan College Team to Shed Light on Art of Shilahara Dynasty. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Pilar Seminary Museum. n.d. The Kadambas of Goa. https://pilarmuseum.org/the-kadambas-of-goa/

Richa Shah. Sindhudurg fort: The 1664 architecture marvel constructed on an island. Rethinking the Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-st…

Richard M. Eaton. 2006. A social history of the Deccan, 1300–1761: eight Indian lives. Cambridge University Press. Rethinking The Future.

The Imperial Gazetteer of India. 1908. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

The Metro Gnome. 2012. Neolithic Rock Art Sites Found in Maharashtra. The Metro Gnome. https://www.themetrognome.in/places/neolithi…

Vocal Media. n.d. Why is Devgad Alphonso the Best Compared to Other Mango Varieties? https://vocal.media/feast/why-is-devgad-alph…

Websites Referred: Sakharam Madhav: Digital District Repository Detail, Sindhudurg District: Official Website, Wikipedia, Sahapedia.

Last updated on 18 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.