Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Early Settlement Site at Narkhed

- Mauryan Influence in the Kuntala Region (c. 3rd Century BCE)

- From the Satavahanas to the Early Chalukyas (c. 2nd Century BCE – 6th Century CE)

- The Rise of the Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas

- Pandharpur in Rashtrakuta Inscriptions (c. 6th Century CE)

- From the Later Chalukyas to the Yadavas (c. 10th – 13th Century CE)

- Harihareshwar Mandir at Hattar Sangudal

- Solapur under Yadava Rule (c. 1184–1318 CE)

- Yadava Patronage and Hemadpanti Architecture in Solapur

- Inscription of Yadava King Mahadevaraya, Mahim village (1269 CE)

- Sant Chokamela

- Sant Savata Mali

- Medieval Period

- The Late Yadava Period and the Sultanate's Arrival

- Solapur under the Bahmani Sultanate (c. 1347–1489 CE)

- Solapur under the Deccan Sultanates (c. 1489–1636 CE)

- Early Contests for Solapur and Paranda

- The Solapur Fort as a Diplomatic and Military Asset

- The Rise of Malik Ambar and Solapur in the Mughal-Nizam Shahi Conflict

- Mughal Intervention and the Transfer of Solapur to Bijapur (1636 CE)

- Aurangzeb's Presence at Machnur Fort

- The Maratha Ascendancy

- Chhatrapati Shivaji (c. 1630–1680)

- Chhatrapati Shahu and the Early 18th Century

- The Akkalkot state and Lokhande Bhosales

- The Peshwa Period (c. 1720–1795)

- Battle of Pandharpur (1774)

- Loss of Nizam’s Territories in Solapur

- The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1815–1818)

- Battle of Ashta (1818)

- Siege of Solapur (1818)

- Colonial Period

- Early Colonial Land Survey and Taxation

- The Rise of Solapur's Textile Industry

- Trade in Solapur During the Colonial Period

- Arrival of the Railway in Solapur District

- The Famine of 1876-79

- Mill Workers and the Rise of Worker Resistance

- Salt Satyagraha and Imposition of Martial Law in 1930

- Post-Independence

- Sources

SOLAPUR

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

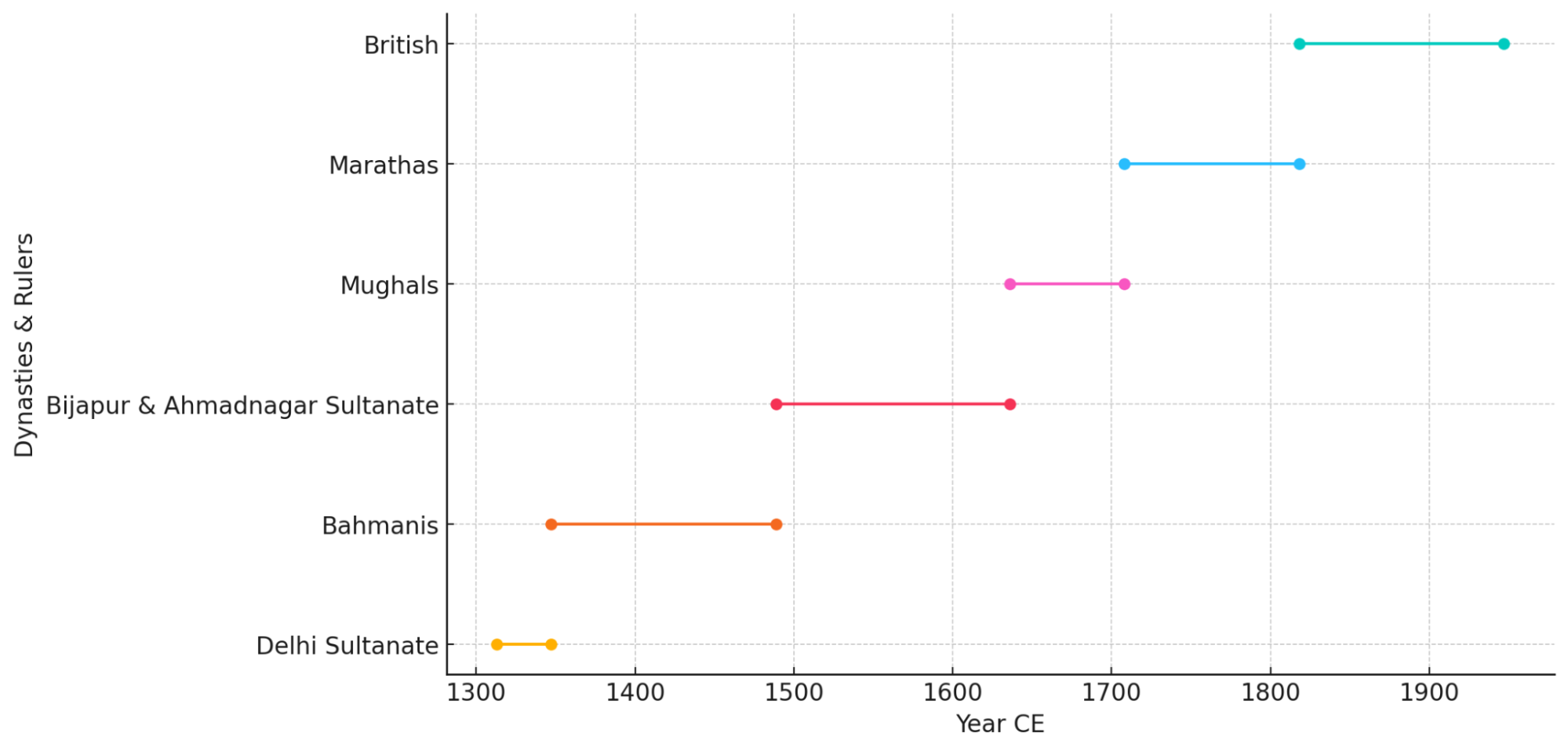

Like any other district, Solapur too has a rich and diverse historical legacy. It witnessed the rise and fall of several dynasties and empires over the centuries. Its historical significance dates back to ancient times when it was part of the Kuntala kingdom, which was then an important political entity in the region. Over time, Solapur became integrated into the vast empire of Ashoka, the great Mauryan emperor renowned for his administrative reforms and the spread of Buddhism. Following the Mauryan era, the district came under the rule of the Satavahana dynasty, which played a crucial role in promoting trade, art, and culture across South India. In the ensuing centuries, Solapur's political landscape evolved under the influence of powerful dynasties such as the Vakatakas, Rashtrakutas, and Chalukyas, who left a lasting impact through their architectural and cultural contributions. During medieval times, the region experienced the dominance of the Delhi Sultanate, followed by the Bahmani Sultanate. However, it was with the emergence of the Marathas that Solapur gained renewed prominence, becoming an integral part of their expanding empire in Maharashtra.

Etymology

The etymology of the name ‘Solapur’ is subject to multiple explanations. One popular account suggests that the name is a compound of two words: Sola, meaning ‘sixteen,’ and Pur, meaning ‘village,’ referring to a belief that the modern city was once an agglomeration of sixteen settlements.

A second, historically grounded theory traces the name’s evolution from an earlier form, ‘Sonnalage.’ Inscriptions from the time of the Kalachuris of Kalyani, associated with the Lingayat saint Shivayogi Shri Siddheshwar, confirm that the town was known by this name. By the Yadava period, the pronunciation had shifted to ‘Sonnalagi.’ Later inscriptions found at Kamati in Mohol taluka and within the Solapur fort indicate further variations, such as ‘Sonalipur’ and ‘Sonalpur.’ It is widely believed that the present-day name ‘Solapur’ emerged from ‘Sonalpur’ through a gradual linguistic shift, where the syllable ‘na’ was eventually dropped.

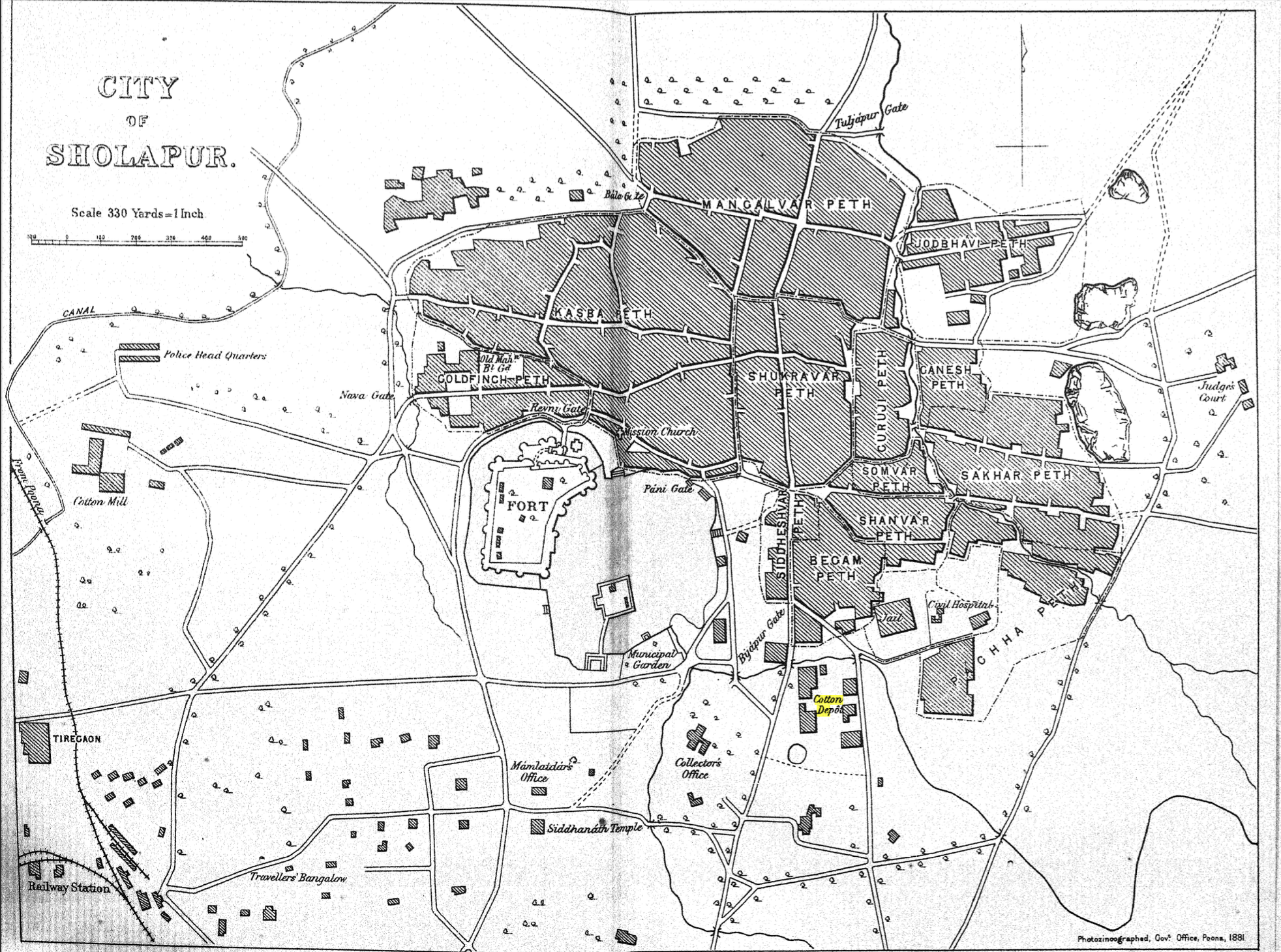

During the period of British rule, the name was officially anglicized and recorded as ‘Sholapur, and this spelling remained in use through much of the colonial era.

Ancient Period

Over the course of history, the region now forming Solapur district has fallen under the influence of many different political and cultural powers. Little is currently known about its earliest history; however, archaeological remains from neighboring regions and later inscriptions offer insights into the district’s past. These are better understood when placed in the context of the Deccan plateau, to which Solapur has long been linked by geography, political influences, and culture.

Early Settlement Site at Narkhed

One of the earliest traces of human presence in Solapur comes from an Iron Age settlement site, representing a crucial phase of technological and social development that followed the Chalcolithic period, in the village of Narkhed in Mohol taluka. Excavations conducted here around 2019–20 have unearthed a settlement dating to the Pre-Satavahana period (c. 4th–3rd century BCE).

The most significant discovery at the site is a sophisticated underground grain storage system, known locally as a ‘pev’. These pits, measuring approximately 20 ft. deep and 4 ft. wide, were likely used to store grains and spices, indicating a settled, agricultural way of life. These granaries are considered among the oldest such structures discovered in Maharashtra. This finding is crucial as it provides the first concrete evidence of a well-established community in Solapur during the protohistoric period, confirming that the district was home to some of the state's earliest settlements.

Mauryan Influence in the Kuntala Region (c. 3rd Century BCE)

In the 3rd Century BCE, among the many dynasties that held sway over the Deccan, the Mauryan Empire under the reign of Emperor Ashoka was pre-eminent. Inscriptions from the period suggest that the region of Kuntala, which is believed to have included parts of the modern Solapur district, likely fell within the Mauryan sphere of influence. This is supported by Ashoka’s fifth and thirteenth rock-edicts, which mention communities such as the Rashtrika-Petenikas and Bhoja-Petenikas. Scholarly interpretations suggest these groups were located in Pratisthana (present-day Paithan in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district) and Vidarbha, respectively. Given Solapur’s geographical proximity to these areas, it is probable that the district came under their influence. Furthermore, the discovery of minor rock edicts of Ashoka in the neighboring Karnul district (currently in Andhra Pradesh, situated to the south-east of Solapur) leaves little doubt that the Kuntala country, comprising the Solapur region, was included in the Mauryan Empire.

From the Satavahanas to the Early Chalukyas (c. 2nd Century BCE – 6th Century CE)

Following the Mauryan period, the Satavahana dynasty (c. 2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE) rose to become the dominant power in the Deccan. During this era, the central Deccan was a mosaic of territories with distinct names. The region north of the Godavari River, with its capital at Pratishthana (modern Paithan), was known as Mulaka. To its south lay the country of Ashmaka, which encompassed areas of modern Ahilyanagar and Beed districts. Over time, this southern region was absorbed into the larger territory of Kuntala, a vast province that extended further south and is believed to have included the modern Solapur district.

The decline of the Satavahanas around 250 CE ushered in a period of political fragmentation. A series of smaller powers succeeded them, beginning with the Abhiras and their feudatories, the Traikutaks. Subsequently, the region appears to have come under the dominion of the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakataka dynasty. A fragmented verse found in the Ajanta caves records a Vakataka ruler’s conquest of Kuntala, reinforcing their influence in the area. After the downfall of the Vakatakas, the Vishnukundins briefly occupied the territory.

The Rise of the Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas

By the 6th century CE, the political landscape of the Deccan shifted once again as the Vishnukundins were ousted by the Chalukyas of Badami, who established firm control over southern Maharashtra. Known as Kuntaleshvaras (lords of Kuntala), the Chalukyas established their capital at Manapura (modern Man in Satara district). Their influence was such that the neighboring territory, including parts of modern Satara and Solapur districts, came to be known as Mana-desha. After approximately a century of Chalukyan rule, they were displaced by the Rashtrakutas, who emerged as the next dominant power in the region.

Pandharpur in Rashtrakuta Inscriptions (c. 6th Century CE)

The earliest known historical reference to Pandharpur dates to the Rashtrakuta period, found in a copper plate inscription from 516 CE. Archaeological evidence further indicates that Rashtrakuta kings made considerable contributions to the mandirs in Pandharpur, which was then already emerging as a pilgrimage center.

From the Later Chalukyas to the Yadavas (c. 10th – 13th Century CE)

With the decline of the Rashtrakutas, the Western Chalukyas (also known as the Later Chalukyas of Kalyani) rose to prominence, ruling over Maharashtra from approximately 975 CE to 1184 CE. Their architectural patronage left a lasting mark on the district.

Harihareshwar Mandir at Hattar Sangudal

A significant trace of this era is the Harihareshwar Mandir, a Chalukyan-era structure discovered in 1999 at Hattar Sangudal village. According to local accounts, the Mandir is unique in that it unites devotees of both Vishnu (Hari) and Shiv (Har), featuring two separate garbhagrihas. The Mandir also displays the fine carvings and decorative attention characteristic of Chalukyan architecture. Its most remarkable feature is a Bahumukhi (multi-faced) Shivling, which boasts 359 intricately carved facial expressions, a feat of craftsmanship believed to be unparalleled in ancient Indian mandirs.

Solapur under Yadava Rule (c. 1184–1318 CE)

Following the decline of the Western Chalukyas, the Yadavas of Devagiri rose to become the main power in the Deccan. In the last quarter of the 12th century, a Yadava prince named Bhillama V successfully challenged his former rulers. After leading victorious campaigns against the Hoysalas, Paramaras, and Chalukyas, he established his capital at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad) and took control of the territory north of the Krishna River.

Evidence from a stone inscription at Mardi in Solapur district confirms the Yadava presence, noting that Bhillama V conquered the Solapur territory from the Kalachuris sometime after 1182 CE. The inscription, which records grants made to the god Yogeshvara, dates Bhillama V's ascension to the throne to approximately 1184 CE, cementing his role in bringing Solapur under Yadava administration.

Under Bhillama’s successors, Yadava influence in the district deepened. His son, Jaitugi, and grandson, Singhana, expanded the kingdom’s power significantly. Several inscriptions from Singhana’s reign found across the Solapur district attest to a well-established administration. An inscription at Pulunj, a village near Pandharpur, records a land grant made by Singhana and lists numerous surrounding villages, many with Kanarese names, highlighting the linguistic and administrative landscape of the time. Further inscriptions from the reign of King Ramachandra, discovered at Velapur in Malshiras taluka, detail the construction of local mandirs and the granting of tax exemptions by Yadava officials, which hint at their direct involvement in the region's governance.

Yadava Patronage and Hemadpanti Architecture in Solapur

The Yadavas' rule also left an indelible mark on the architectural landscape of Solapur district. Under their rule, various mandirs were built in the district, reflecting the distinct Hemadpanti style of architecture, which became popular under the patronage of the Yadava minister, Hemadpant. This style is characterized by the use of locally sourced black stone and a dry masonry technique, where large, dressed stones are fitted together without mortar.

A notable example of this architectural patronage is the Ardhanari Nateshwar Mandir at Velapur. Also known as the Hara Nareshwara Mandir, it was constructed in the 12th century CE during the reign of King Ramchandra Dev and showcases classic Hemadpanti features. According to local tradition, Velapur’s name signifies its role as the southern boundary of the Devagiri kingdom (vel meaning boundary and pur meaning village), and the town served as an important military and administrative sub-capital for the Yadavas.

The Mandir is famed for its distinctive murti depicting Mahadev on the right and Devi Parvati on the left, symbolizing the union of divine energies. Its intricate carvings are attributed to the brothers Bramhadev and Baidev Raina. The Mandir complex also features a large square water tank and other sculptures, including those of Hanuman and Bhairav. Inscriptions found on its walls suggest later renovations, including the installation of two facing Nandi statues, a unique feature for a Mandir of this period.

Another notable site from this period is the Bhagwant Mandir in the town of Barshi. Constructed in 1245 CE, this Mandir dedicated to Bhagwan Vishnu is believed to be the only one in India bearing the name "Bhagwant." It stands as a significant architectural marvel in the Hemadpanti style, its construction attributed to the influence of Hemadpant himself.

Sites like the Aklai Devi Mandir at Akluj are believed to have gained prominence during the Yadava era. While local legends place the Mandir’s origins further back in time, historical accounts and traditions suggest that Akluj was a place of significance throughout the Yadava period, indicating the Mandir’s long-standing importance in the region’s cultural and religious life.

Inscription of Yadava King Mahadevaraya, Mahim village (1269 CE)

Direct evidence of this royal patronage comes from a stone inscription dated to 1269 CE, discovered in the Mahim village of Sangola taluka. The inscription, belonging to the reign of Yadava King Mahadevaraya (c. 1260–1270), was found carved on a large rectangular slab. The inscription comes from the Seuna Yadava Dynasty, which ruled from Devagiri (Daulatabad) from around 1187 to 1317 CE. Solapur district, then known as Sonnalage or Sonalipur, was a major trade and religious hub under the Yadavas.

The inscription itself, written in Devanagari script, transitions from Sanskrit to an early form of Marathi. It records a specific act of royal support: a donation of 20 gadyanas (gold coins) by King Mahadevaraya for the construction of a Mandir in Mahim. The slab also features carvings of a sun, moon, a cow with its calf, and a sword - symbols common to Yadava-era grants.

As possibly the first known record of King Mahadevaraya found in Solapur district, this inscription offers tangible proof of the Yadava dynasty’s support for Mandir construction and highlights their role in promoting the Marathi language.

Sant Chokamela

Chokhamela was a 13th–14th century saint from Maharashtra, India. He was born in Mehuna Raja, a village in Deulgaon Raja Taluka of Buldhana district, and belonged to the Mahar community, which was considered a low caste at the time. He later lived in Mangalvedha, Maharashtra.

Chokhamela was introduced to the bhakti (devotional) path by the poet-saint Namdev (1270–1350 CE). During a visit to Pandharpur, he heard Namdev’s kirtan (devotional singing), which deeply inspired him. Profoundly influenced by Namdev’s teachings, Chokhamela later made Pandharpur his home. A devoted follower of Lord Vitthal (Vithoba), Chokhamela composed numerous Abhangas (devotional poems), among which “Abir Gulal Udhlit Rang” is especially well known. He is regarded as one of the earliest poets from the lower castes in India.

Sant Savata Mali

Savata Mali was a 12th-century Hindu saint and a contemporary of Namdev, known for his deep devotion to Lord Vithoba. His grandfather, Devu Mali, relocated for financial reasons to Arangaon (also known as Aran-behndi), near Modnimb in the Solapur district. Devu Mali had two sons — Parasu (Savata’s father) and Dongre. Parasu married Nangitabai, and although they lived in poverty, they remained devoted followers of the Bhagwat faith. Dongre passed away at a young age. In 1250, Parasu and Nangitabai were blessed with a son, Savata Mali.

Raised in a deeply religious household, Savata later married Janabai, a devout Hindu woman from Bhend village. While tending his fields in Aran, Savata Mali would sing praises of Lord Vithoba. It is believed that since Savata could not undertake a pilgrimage to Vithoba’s temple, the deity himself appeared before him. Today, a temple dedicated to Sant Savata Mali stands in Aran in his honor.

Medieval Period

The medieval era in Solapur began with the end of local Yadava rule, pulling the district into centuries of conflict. It became a key battleground for the rival Deccan Sultanates and the Mughal Empire, with its strategic forts changing hands numerous times. The period concluded with the rise of the Marathas, who established Solapur as a vital military and administrative hub.

The Late Yadava Period and the Sultanate's Arrival

Towards the end of the 13th century, the Deccan region experienced a shift with invasions from the Delhi Sultanate. In 1296, Alauddin Khilji led a raid on Devagiri, forcing the Yadavas to pay tribute. Although the dynasty persisted for two more decades, its authority was severely weakened, and by 1318, its kingdom was fully annexed, bringing the region under the control of the Sultanate.

Solapur under the Bahmani Sultanate (c. 1347–1489 CE)

In the mid-14th century, as the authority of the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan weakened, the region entered a new political era with the rise of the Bahmani Sultanate. In 1347, Ala-ud-Din Bahman Shah, a former officer under the Tughlaq administration, took advantage of the instability and declared independence. To govern his new kingdom, he divided it into four large provinces, or tarafs. Due to its strategic location, the Solapur region was incorporated into the Gulbarga taraf, the province surrounding the capital. To consolidate their power, the Bahmanis focused on military and administrative control, and the forts within Solapur district, particularly at Paranda and Solapur itself, grew in strategic importance.

Life under Bahmani rule, however, was marked by both administrative efforts and severe hardship. The region was struck by the devastating Durgadevi Famine, which lasted from 1396 to 1407. The prolonged drought led to widespread starvation and mass depopulation across the Deccan, including in Solapur district. The Bahmani state attempted to provide relief by importing grain from Gujarat and establishing orphanages, but the famine’s long duration overwhelmed these efforts. It was only after the return of rains in 1429 that the area began a slow recovery.

Later in the 15th century, during a period of administrative reorganization under Prime Minister Mahmud Gawan, the administration of Solapur and Paranda was placed under the authority of a governor named Khwaja Jahan. This move aimed to strengthen central control over key territories. However, Gawan's reforms provoked opposition from the nobility, leading to his execution in 1481 and triggering the rapid fragmentation of the Bahmani kingdom. This collapse paved the way for the rise of the rival Deccan Sultanates, who would vie for control of Solapur in the coming century.

Solapur under the Deccan Sultanates (c. 1489–1636 CE)

Following the fragmentation of the Bahmani kingdom, Solapur district emerged as a volatile and highly contested frontier, caught between the two most powerful successor states: the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur to the south and the Nizam Shahi dynasty of Ahmadnagar to the north. For over a century, control over the district, and particularly its formidable fort, became a central issue in the relentless power struggle that defined Deccan politics.

Early Contests for Solapur and Paranda

The initial division of territory saw Solapur fall into a zone of intense conflict. According to the Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (1883), Yusuf Adil Shah of Bijapur expanded his rule northward up to the Bhima River in 1489, incorporating parts of present-day Solapur into his new kingdom. However, the Partition Treaty of 1497 between the Sultanates assigned the nearby fort of Paranda to Ahmadnagar's (current Ahilyanagar) sphere of influence, leaving the fort of Solapur and its surrounding districts as a point of contention.

This ambiguity led to frequent shifts in power. Although Bijapur initially held sway, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate’s influence grew, and by 1511, Bijapur had to recapture Solapur by force. The district’s strategic importance was such that it remained a primary military objective for both kingdoms for decades.

The Solapur Fort as a Diplomatic and Military Asset

The Solapur fort became more than just a military asset during this time; it was also a key asset in treaties and royal alliances. In 1523, a royal marriage was arranged between the two sultanates in an attempt to broker peace, with the Solapur fort intended as part of the dowry. However, the alliance quickly soured, leading to renewed conflict.

In the 1540s, Ibrahim Adil Shah of Bijapur temporarily lost control of five and a half districts of Solapur to Ahmadnagar. He launched a successful counterattack, forcing Burhan Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar to sue for peace and return the territory. The peace was short-lived, as Ahmadnagar, in alliance with other Deccan powers, again attempted to reclaim the region, nearly overwhelming Bijapur in a multi-front war.

Later in the 16th century, the fort was formally ceded to Bijapur as part of the dowry of Chand Bibi, the princess of Ahmadnagar, upon her marriage to the Bijapur Sultan. Yet even this high-profile alliance failed to permanently settle the dispute, as Ahmadnagar soon renewed its attempts to reclaim this territory.

In the late 17th century, as part of the marriage alliance, the Solapur fort and its surrounding area were given as dowry. The fort's design is in the style of the Bahamani era. It is currently protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

The Rise of Malik Ambar and Solapur in the Mughal-Nizam Shahi Conflict

The turn of the 17th century brought another major power into the politics of the Deccan: the Mughal Empire. In 1600, Mughal forces captured the city of Ahmadnagar (present-day Ahilyanagar), the capital of the Nizam Shahi Sultanate. However, this did not lead to an immediate consolidation of Mughal power. In the aftermath, a formidable figure emerged to lead the Nizam Shahi resistance: Malik Ambar, an Abyssinian-born military commander and statesman.

Though the Mughals held the Ahmadnagar fort, Malik Ambar established a new, de facto Nizam Shahi state, first from Paranda in nearby Dharashiv and later from Khadki (present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar). For nearly three decades, he successfully challenged Mughal expansion in the Deccan. His influence extended into the northern parts of Solapur district, which prospered under his renowned land revenue system. This system, which replaced revenue-farming with direct, systematized collection, brought stability and wealth to the territories under his control.

In 1623, demonstrating his military prowess, Malik Ambar laid siege to the fort of Solapur, briefly bringing this key stronghold under his administration. However, this period of resurgence was followed by a severe famine between 1629 and 1630, which, accompanied by a pestilence, devastated the region and hastened the decline of the revived Nizam Shahi state.

Mughal Intervention and the Transfer of Solapur to Bijapur (1636 CE)

The decline of the Nizam Shahi state, hastened by the death of Malik Ambar and the devastating famine of 1629-30, created a power vacuum that the Mughal Empire moved decisively to fill. The long-standing rivalry over the Deccan's territories was finally settled through imperial intervention.

In 1636, a treaty was concluded between the Mughals and the Bijapur Sultanate. Under this agreement, the long-contested forts of Solapur and Paranda were formally transferred to the rule of Mahmud Adil Shah of Bijapur. This treaty not only marked the official end of the Nizam Shahi dynasty but also resolved, for a time, the century-long struggle for control over the region. For the next thirty years, Solapur enjoyed a period of relative stability under the consolidated authority of the Bijapur Sultanate.

Aurangzeb's Presence at Machnur Fort

A unique trace of Mughal presence in the district comes from Machnur village in Mangalvedhe taluka. According to local tradition, a fortress was built here by Emperor Aurangzeb around 1695 CE. The story is tied to the nearby Siddheshwar Mandir. It is said that after taking control of the area, Aurangzeb ordered a Shivling in the Mandir to be destroyed. When his soldiers were thwarted by a swarm of bees, he sent a disrespectful offering that miraculously transformed into flowers. Ashamed, Aurangzeb is believed to have begun making annual donations to the Mandir and even initiated the Rudrabhishek ceremony there, providing financial support for the rituals. He is said to have spent four years at this camp, using the fortress as a base for overseeing his southern campaigns. This account, preserved in local memory, offers a fascinating glimpse into the complex interactions between Mughal authority and local religious traditions in Solapur.

The Maratha Ascendancy

In 1665, the Mughals, aiming to weaken Bijapur, allied with Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, launching a campaign in the region. By 1685, Mughal general Shaista Khan advanced towards the Bijapur borders, and in the following year, the Mughals annexed the entire Bijapur Sultanate, including the district. Solapur remained part of the Mughal Deccan province until the early 18th century.

Chhatrapati Shivaji (c. 1630–1680)

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj became deeply involved in the district's affairs, initially through a temporary alliance with the Mughals and then by joining the campaign of Mughal commander Jaysing. While his forces captured several surrounding locations, they were unable to take the fort itself. Ironically, diplomacy soon achieved what military force could not: a treaty in 1668 transferred Solapur to Mughal control, bypassing Shivaji’s efforts.

When the Mughals attacked Bijapur in 1679, Shivaji was called to assist. Finding the siege impenetrable, he diverted his forces and raided Mughal possessions between the Bhima and Godavari rivers. In 1686, Aurangzeb set up his camp in Solapur before marching to Bijapur for its final siege. The prolonged conflict devastated Solapur’s economy. In 1689, Shivaji’s son, Sambhaji, was captured by the Mughals, escalating hostilities.

The Akluj Fort in Solapur, located on the banks of the river Nira, stands as a legacy of this period. A section of the renovated fort, known as Shivsrushti, showcases the life of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj through sculptures and murals depicting key moments from his life.

Chhatrapati Shahu and the Early 18th Century

Chhatrapati Shahu ji was instrumental in reclaiming Solapur for the Marathas. He allied with Syed Husain Ali Khan, the Mughal Viceroy of the Deccan, and in exchange for his support, was granted control over the region east of Pandharpur in 1719. However, the Nizam, consolidating power in the Deccan, captured the remaining Mughal territories in Solapur by 1723. This led to a revenue-sharing agreement and frequent conflicts between the Nizam and the Marathas.

The Akkalkot state and Lokhande Bhosales

Shahu adopted Ranoji Lokhande, later known as Fatehsinh I Raje Sahib Bhonsle was the son of Meherban Sayaji Lokhande, Patil of Parud. Sayaji Lokhande, a loyalist of Tarabai, had died during Chhatrapati Shahu’s sack of Parud in the Maratha conflict between Tarabai and Shahu I. Tradition holds that Ranoji’s mother placed him in Shahu’s palanquin after the sacking, leading to his adoption. Around 1708, Ranoji took the name Fatehsinh Bhonsle and was granted the town of Akkalkot along with the surrounding areas. He thus became the first Raja of Akkalkot and founder of the Lokhande Bhosale dynasty. These estates remained under the Satara state until 1848, when the British deposed the Chhatrapati of Satara and recognized Akkalkot as a separate princely state.

The Peshwa Period (c. 1720–1795)

In 1750, a rebellion by Sadashivrao Bhau, who took refuge in the fort of Sangola, was suppressed by Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao. In 1761, after the Maratha defeat at Panipat, Nizam Ali of Hyderabad ravaged Pune but was checked. A treaty was made, but the Nizam soon allied with Janoji Bhosale. The Marathas, avoiding direct conflict, ravaged Solapur and Naldurg. The issue was decided at the Battle of Rakshasbhuwan in 1763, where the Nizam's forces were routed, and he surrendered territory worth 82 lakhs to the Marathas.

In 1766, Peshwa Madhavrao captured the forts of Solapur and Wandan from Babuji Naik Joshi of Baramati, who had resisted the Peshwa's authority.

Battle of Pandharpur (1774)

In 1774, after his nephew's murder, Peshwa Raghunathrao faced opposition from his ministers. A clash occurred at Pandharpur on March 4, 1774, where Raghunathrao, despite being outnumbered, achieved a decisive victory. This triumph briefly revived his reign, but his prospects ended with the birth of a posthumous son to the murdered Peshwa Narayanrav.

Loss of Nizam’s Territories in Solapur

The relationship between the Marathas and the Nizam deteriorated over a dispute about the chauth (tax). On 11 March 1795, a conflict resulted in a decisive Maratha victory, forcing the Nizam to relinquish a significant portion of his territory, including possessions in Solapur. The following years were marked by turmoil within the Maratha state, which the rising British power exploited.

The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1815–1818)

By the early 19th century, Solapur was a contested region between the declining Maratha Empire and the rising British. The murder of Gangadhar Shastri in 1815 in Pandharpur, under the guarantee of British safety, heightened tensions and set the stage for the Third Anglo-Maratha War.

Battle of Ashta (1818)

The Battle of Ashta in 1818 was one of the final battles of the war. After his defeat at Kirkee, Peshwa Baji Rao II fled through Pandharpur and Solapur. British forces under General Smith confronted the Maratha army at Ashti village. In the struggle, Bapu Gokhale, the Peshwa’s most trusted general, was killed. His death marked the end of effective Maratha military resistance and led to the Peshwa’s surrender, paving the way for the British takeover of Solapur.

Siege of Solapur (1818)

The Siege of Solapur in April 1818 further consolidated British control. After his campaign in Bombay-Karnataka, General Monro advanced on Solapur, where the Peshwa’s elite infantry had retreated. After receiving reinforcements, Munro's army forced a siege of the town and its fort.

The British launched a full-scale assault, breaching the town's defenses. The Maratha garrison, facing superior firepower and heavy casualties, eventually surrendered. The British captured the fort and its 37 cannons. The capture of this important fort deprived the Peshwa’s troops of their last rallying point in the region. With the end of the war, Solapur was annexed by the British and became part of the Bombay Presidency, marking a significant shift from a Maratha stronghold to British colonial administration. This transition also disrupted local industries, particularly weaving, as artisans and traders were displaced by the conflict.

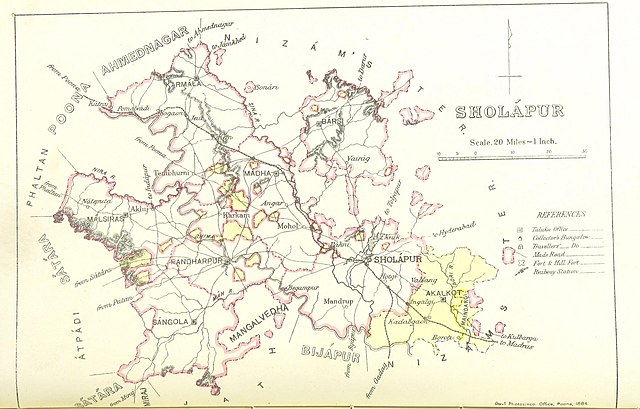

Colonial Period

Following the conclusion of the Third Anglo-Maratha War, the British began the process of integrating the Solapur district into their territories. As a direct result of Peshwa Baji Rao II’s defeat in 1818, the British annexed his domains, which included 92 villages in Solapur along with other nearby regions. This marked the formal beginning of colonial administration in the area. Subsequently, in 1822, the Nizam of Hyderabad ceded 38 villages in Solapur to the British under a treaty. Between 1839 and 1870, further territorial changes occurred. For instance, in 1839, following the death of the local feudatory chief of Nipani, a nearby principality, 11 of his villages located within Solapur were annexed by the British under their policy of lapse. Decades later, in 1870, the district’s boundaries shifted again when the Nizam of Hyderabad ceded an additional 11 villages to the British as part of a land exchange agreement.

While direct British administration expanded across Solapur, the princely state of Akkalkot maintained a distinct political identity within the district. Originally an estate granted to the Bhonsle dynasty, Akkalkot was recognized by the British as a separate state in 1848. For the remainder of the colonial era, it existed as an island of princely rule, administered as part of the Deccan States Agency and surrounded by territories managed directly by the British and the Nizam.

Early Colonial Land Survey and Taxation

In 1840-41, the British introduced survey settlements in Solapur and Ahirwadi village groups, covering a 12 to 15-mile radius around Solapur town. The first survey was conducted between 1838 and 1839. According to the Gazetteer (1884), of the 2,56,878 acres surveyed, out of which 2,10,996 acres were deemed suitable for cultivation, while the rest were wastelands or designated as pasture lands. The district was considered challenging for agriculture due to its dry climate, lack of irrigation, and soil conditions. Only 10% of the surveyed land had fertile black soil, while the rest was a mix of red and gravelly soil, with limestone layers near the Sina River.

According to the Gazetteer (1884), taxation in Solapur was considered to be burdensome under Peshwa rule, especially during the tenure of Mankeshwar, who had increased rent and land tax (ukat), placing a heavy burden on farmers. By 1839, Solapur’s farmers began protesting against high taxes, particularly rising leases on kauls (land contracts) and additional land charges. Before British rule, taxes were collected under the mamul (customary) system, where villages paid different rates depending on soil quality. Some villages had up to six or seven different tax rates, making the system highly inconsistent and oppressive. When the British took over, they attempted to standardize taxation through land surveys, but tax burdens remained high.

Between 1824 and 1856, under the British government, the district faced severe economic hardships due to recurring famines and epidemics. The famine of 1832-34 and 1838-39 led to widespread crop failures, worsened by rat infestations that destroyed grain supplies. Between 1839 and 1859, a major cholera outbreak further reduced the population, affecting the region’s labor force and overall agricultural productivity. These conditions hampered economic stability, making it difficult for farmers to meet tax demands.

The Rise of Solapur's Textile Industry

As Solapur transitioned into the colonial era, its economy underwent a profound transformation centered around its textile industry. For centuries, the district had been known for its handloom weaving, an industry reliant on the skill of local artisans. However, the late 19th century witnessed a decisive shift from traditional handlooms to mechanized production with the establishment of large-scale cotton mills. This development would come to define Solapur's modern identity.

According to the district Gazetteer (1977), the district in 1872 had a thriving artisan community with a significant number of weavers, dyers, and spinners. The turning point came in 1874, with the establishment of the first textile mill by Seth Morarji Gokuldas of Mumbai. The region proved to be an ideal location for such an enterprise due to several factors: a large pool of cheap labor made available by frequent famines, adequate water resources, and a pre-existing skilled workforce of weavers.

The success of the first mill spurred further industrialization. In 1898, two more mills were founded: the Laxmi Cotton Mill by Seth Laxmidas Khimji and the Narsinggirji Mill by Mallappa Warad. While Seth Morarji was a pioneer, it was Mallappa Warad who is widely credited with laying the foundations of modern business and industry in Solapur. By the early 20th century, the city's mills were employing over 31,000 workers. The output from these mills grew significantly during World War I and solidified Solapur's reputation as a leading hub of textile manufacturing in Western India.

A lasting legacy of this rich textile tradition is the Solapuri Chaddar, a distinctive cotton blanket renowned for its unique designs and durability. In a testament to its cultural and economic significance, the Solapuri Chaddar became the first product from Maharashtra to be granted Geographical Indication (GI) status, formally recognizing its unique origin and heritage.

Trade in Solapur During the Colonial Period

During this time, Solapur's location positioned it as a vital trade hub for centuries. Throughout history, it served as a key waypoint on major Deccan trade routes, connecting the region's rich agricultural produce and handcrafted goods with coastal ports.

One such prominent route linked Solapur with Chaul, a bustling port on the western coast. This route facilitated the exchange of goods between the Deccan plateau and international markets. Later, under British rule, the rise of Mumbai as a major commercial center further amplified Solapur's significance. The city became a crucial link in the supply chain, channeling goods from the Deccan towards the booming port city. According to the Gazetteer (1884), some of the trade centres in the district were Barsi, Solapur, and Pandharpur. These cities thrived by offering a platform for local artisans and farmers to exchange their wares.

Arrival of the Railway in Solapur District

The arrival of the railways dramatically transformed the district's economic landscape. In 1856, the extension of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (established in 1853) reached the district, connecting it to key commercial hubs like Mumbai and Pune. This vital link spurred internal and external trade, opening new avenues for the district’s booming textile industry.

The railway network continued to expand in 1865 with the commencement of construction southwards from Solapur. Later, the East Deccan Railway, established towards the end of the 19th century, further strengthened Solapur's connectivity, forging a vital link between South Maharashtra and Karnataka. These developments transcended mere economic benefits. The efficient transportation network proved invaluable during the Indian independence movement, facilitating communication and troop movement across the region.

The Famine of 1876-79

Despite its growing industrial and commercial importance, the district remained vulnerable to agrarian crises. According to the Gazetteer (1977), Solapur has a long history of devastating famines, often triggered by the failure of seasonal rains. The Great Famine of 1876–79, caused by insufficient rainfall and widespread crop failure, resulted in severe hunger, malnutrition, and death across the region.

The British colonial government responded by implementing relief measures, including public works programs like dam and well construction to provide income, the establishment of relief houses, and the large-scale import of grain. The scale of the grain import via the newly built railways was so immense that stations were reportedly overwhelmed with bags. This crisis exposed the profound vulnerability of the region and catalyzed future infrastructure projects aimed at mitigating the impact of drought.

The district was hit again by an even more severe cycle of famines beginning in 1896, with the effects lasting for over a decade. As detailed in the Gazetteer (1977), the famine of 1896–97 affected the entire district. At its peak, over 1,32,000 people were receiving relief. When the rains failed again in 1899–1900, the situation worsened dramatically. The crop yield fell to just 17% of normal, and at the height of this famine, the number of people on relief soared to over 1,71,000, with special aid provided to the district's weavers to support their craft. The death rate climbed to nearly 57 per million, and thousands perished from dysentery, cholera, and malnutrition. These repeated famines underscored the precariousness of life in the region and the immense challenge of survival for its agricultural and artisan communities.

Mill Workers and the Rise of Worker Resistance

In 1912, the colonial government established a "criminal tribes" settlement in Solapur. This settlement, later managed by the American Marathi Mission (1918), housed members of specific communities (Chhaparbands, Kaikadis, Ghanticors, Haranshikaris, and Manggarudis) who were branded as criminals. These men, women, and children were then forcibly recruited to work in the city's textile mills, constituting a significant portion of the workforce (700-800 out of 18,000).

The practice of employing these "criminal tribes" resembled penal servitude. Unlike the rest of the population, these workers were essentially prisoners within the city limits, even during outbreaks of disease. This system benefited both the government and mill owners. The government saved on jail and settlement maintenance costs, while mill owners enjoyed a readily available, cheap labor source, further eliminating the need for famine relief programs during droughts.

This exploitative system fueled worker discontent. The interwar period saw major strikes (1920 and 1922) as workers sought better wages and working conditions. While these strikes were brutally suppressed, they signaled growing worker solidarity. Notably, the 1920 strike, led by Bhimrao and other workers, involved acts of defiance like whistling, throwing tools, and damaging factory property. Despite their efforts, the strike failed, and 13 leaders faced repercussions. The decision not to implement recommendations for improved security measures in Sholapur's mills would come back to haunt the administration a decade later. In 1930, following Mahatma Gandhi's arrest, the city erupted in serious unrest, highlighting the simmering tensions beneath the surface.

Salt Satyagraha and Imposition of Martial Law in 1930

The Civil Disobedience Movement gained significant momentum in Solapur with the launch of the Salt Satyagraha in 1930. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's call, local leaders such as Dr. Antrolikar and Tulsidas Jadhav mobilized widespread participation across the district.

The situation escalated dramatically following the arrest of Mahatma Gandhi. His arrest triggered mass processions and protests in Solapur, which unfortunately led to violence. As unrest grew, police opened fire on demonstrators, and the city's court building was set on fire. In response to these events, the colonial administration took the unprecedented step of imposing Martial Law on Solapur on May 12, 1930. Under military rule, numerous individuals were arrested and tried by tribunals without the opportunity for a standard legal defense. The period of Martial Law continued until June 30, 1931, marking a unique and intense chapter in the city's role in the freedom struggle.

Post-Independence

Solapur has undergone several political and administrative changes since India's independence in 1947. During British rule, as highlighted above, the district was part of the Bombay Presidency, a major administrative division in colonial India. The district was governed under provincial administrative structures, with local administration managed by British-appointed Collectors and District Magistrates. Solapur was divided into multiple talukas, such as Solapur, Barshi, Akkalkot, Pandharpur, Sangola, Mangalvedha, and Karmala, primarily for revenue collection and governance.

Following India's independence in 1947, Solapur remained part of Bombay State until the linguistic reorganization of states in 1960, when it was merged into the newly formed state of Maharashtra due to its predominantly Marathi-speaking population. After becoming part of Maharashtra, Solapur district underwent multiple administrative changes, including the restructuring of talukas for better governance. Some talukas were split or renamed, such as the separation of Mangalvedha from Pandharpur taluka, while others, like Mohol and Madha, were newly created to accommodate population growth and improve local governance. These changes helped decentralize administration, making government services more accessible while also supporting industrial and infrastructural development. Over time, Solapur evolved into a major hub for textiles, sugar mills, and agro-based industries. Today, the district has 11 talukas, namely North Solapur, South Solapur, Akkalkot, Barshi, Mangalwedha, Pandharpur, Sangola, Malshiras, Mohol, Madha, and Karmala.

Sources

Dhaval Kulkarni. 2023. When archaeologists found pre-historic era storage pits in Maharashtra's Solapur. India Today.https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insigh…

Dhaval S. Kulkarni. 2023. When archaeologists found pre-historic era storage pits in Maharashtra’s Solapur. India Today.https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insigh…

District Census Handbook – Solapur. 2011. Census of India. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

James Campbell, et al. 1884. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Sholapur.Vol. XX. Government Central Press, Bombay.

P. N. Chopra, et al. 1977. Maharashtra State Gazetteer: Solapur District. Gazetteers Department, Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Wikipedia. Akkalkot State. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akkalkot_State

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.