Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Kelzar and Rishi Vashishtha

- The Defeat of Bakasur and the Tondya Rakshas Maidan

- Iron Age Burials at Khairwada

- Megalithic Remains at Yesamba

- The Kingdom of Vidarbha and Early Political Developments

- Paunar & the Satavahana Period

- The Spread of Buddhism and Remains in Pavnar and Dhaga

- The Gavli Rajas and Early Pastoral Traditions in Hinganghat

- Paunar as the Possible Capital of the Vakataka Dynasty

- Deoli Inscription and the Rashtrakutas in Wardha

- Medieval Period

- Offices of Deshmukh and Deshpandia

- The Sarkars of Berar Under the Mughals

- Pratap Rao and the Marathas

- The Gond Kingdoms of East Vidarbha

- Raghuji I Bhosale

- Colonial Period

- First War of Independence, 1857

- Formation of the Wardha district

- Wardha Town

- Pulgaon

- Cotton Production

- Wardha Valley Coal Mine

- Laxminarayan Mandir and the Temple Entry Movement

- Baba Amte

- Vinoba Bhave and the Paramdham Ashram

- Seth Jamnalal Bajaj

- Mahatma Gandhi and the Sevagram Ashram

- Magan Sangrahalaya

- Vishwa Shanti Stupa

- Wardha Congress Working Committee, 1942

- Post-Independence Era

- Sources

WARDHA

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Wardha district, located in the western part of the Vidarbha region in Maharashtra, holds a long and layered history. There are many settlements in the district that attest to its antiquity and one of the clearest signs of this can be found at Khairwada in Karanja taluka, where a vast field of megalithic burials — among the largest in Maharashtra — dates back to the Iron Age. In the centuries that followed, Paunar (present-day Pavnar) emerged as one of Vidarbha’s earliest urban centres. Its prosperity endured for centuries, and by the late sixteenth century the Ain-i-Akbari recorded the region’s wealth and administrative importance. Over time, Wardha came under the influence of multiple ruling powers, such as the Vakatakas, Gonds, the Marathas, and the British, each of whom left their imprint on the region’s landscape. In the 20th century, pivotal figures such as Mahatma Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave made Wardha their base during India’s struggle for Independence.

Etymology

The origin of the district’s name is of enduring interest and has been the subject of varying interpretations. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1906), the district derives its name from the Wardha River, which flows through the region and has long defined its geography. Several explanations have been offered regarding the origin of the river’s name. One traditional account links it to Varaha, the boar incarnation of Vishnu, from whose mouth the river is said to have emerged at the request of a sage who resided in the area.

This interpretation, however, has been questioned by historian Hira Lal (1906), who proposes that the name is formed from the Sanskrit elements Var and Da, meaning "giver of boons," in reference to the river's confluence with the Pranhita. An alternative explanation is provided by General Cunningham, who suggests that Wardha may be a corruption of Waroha or Wadhona—names historically associated with the banyan tree, which is commonly found in the region.

Ancient Period

Kelzar and Rishi Vashishtha

The village of Kelzar, located in the southern part of Wardha district, is among the earliest sites in the region to which local tradition assigns antiquity. It is said to have been inhabited during the Treta Yuga, and is identified in regional belief with Ekchakra Nagar; which is a name that appears in classical Sanskrit texts, such as the Vashistha Purana.

It is believed that Rishi Vashishtha, regarded as the royal priest and spiritual guide in the court of Dasharatha, resided at Kelzar during a period preceding the events of the Ramayan. During his stay here, the Rishi is believed to have consecrated a Mandir dedicated to Ganesh, where the Devta is worshipped under the form of Varad Vinayak. Interestingly, many in the region say that the name of the Wardha River is connected to this Mandir. with this shrine. It is held that the river was once known as Varada, and that its name was derived from this form of the Devta.

The Defeat of Bakasur and the Tondya Rakshas Maidan

Kelzar is also associated with a well-known episode from the Mahabharat which involves the defeat of the rakshas named Bakasur (also referred to as Baka). The event is said to have taken place in Ekachakra, a town mentioned in the epic but not identified with certainty. In the Wardha region, however, Kelzar is commonly believed to be the site referred to.

According to local accounts, Bakasur is believed to have inhabited the vicinity of the village and demanded from its residents the daily sacrifice of a child. This continued until the arrival of the Pandava brothers, who, while in exile, are said to have passed through the area.

The story recounts that the brothers encountered a family selected to make the day’s offering. On learning of the situation, Bhima, the second of the brothers, is said to have resolved to confront the creature. A fierce struggle is believed to have ensued, culminating in Bakasur’s defeat. The location where this encounter is believed to have taken place is known as the Tondya Rakshas Maidan, situated near the Buddha Vihar at Kelzar.

Iron Age Burials at Khairwada

Alongside oral traditions, there are many archaeological sites in the region that attest to its antiquity. Among them, the village of Khairwada, situated in Karanja taluka, contains one of the most extensive megalithic burial sites in Maharashtra. These remains, consisting chiefly of stone-built circles, are generally assigned to the early Iron Age, and represent a material culture common to large portions of peninsular India in the early first millennium BCE.

The site was first recorded in 1871 by J.J. Carey of the Geological Survey of India, whose notes were later communicated to the Asiatic Society. Excavations conducted in 1980–81 by the Department of Archaeology at Deccan College confirmed the presence of over 1,400 stone circles. These are believed to mark burial locations, with associated habitation layers identified on the eastern and northern edges of the village lands. Notably, the scale and distribution of the remains suggest that Khairwada may once have supported a sizable and long-settled community during that time.

Megalithic Remains at Yesamba

Further remains of the Iron Age period are found at Yesamba, a village also located in Wardha district. Here, more than sixty stone circles, many ranging between 4 and 40 metres in diameter, are dispersed across the Yesamba gram panchayat, particularly near the Bhavani Mata Mandir on the road to Bhankheda.

The site was brought to archaeological attention during an ethnographic survey in nearby Khairwada by Oshin Bamb, whose local informants directed him to the remains. The structures are of a type associated with megalithic burial practice, and fragments of red and black ware pottery were also recovered. Such pottery is often linked with early Iron Age settlement in the Deccan.

The remains at Yesamba are presently unprotected. Quarrying and encroachment have already caused visible damage to several structures. Although a formal proposal for conservation is being prepared to be submitted to the relevant authorities, the site remains vulnerable.

The Kingdom of Vidarbha and Early Political Developments

Over time, Wardha seems to have come under the influence of various political and cultural powers. It was historically part of the ancient Vidarbha kingdom, whose mentions frequently appear in ancient Sanskrit literature. Though its political boundaries are debated, most scholars agree that the Vidarbha kingdom encompassed the present-day Vidarbha and Berar regions, with the Wardha River (which passed through the district) often forming an important internal boundary.

By the 3rd century BCE, the region had likely come under the influence of the Maurya Empire and later the Shungas, who established their capital at Pataliputra (modern Patna, Bihar). Under Pushyamitra Shunga, their control extended gradually southward. His son, Agnimitra, appointed as viceroy of the southern provinces at Bhilsa (present-day Vidisha), is said to have encountered resistance from a ruler of Vidarbha.

An account of this episode is preserved in Kalidasa’s drama, Malavikagnimitram. Though primarily a courtly drama, the play includes a subplot involving a military conflict between the Sunga Empire and the kingdom of Vidarbha. In the story, Agnimitra, the son of the Shunga ruler Pushyamitra, is drawn into a dispute with the Raja of Vidarbha. The war ends with the kingdom of Vidarbha divided between two brothers, one remaining as ruler, and the other supported by the Shungas. The Wardha River is mentioned in later accounts as having served as the boundary between the two dominions and Wardha perhaps functioned as a major frontier zone during this period.

Paunar & the Satavahana Period

Later, the Satavahana dynasty, which ruled the Deccan from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE, established control over much of Berar, including what is now Wardha district. Archaeological excavations at Paunar (also spelt Pavnar), which lies within the district, have unearthed a range of artefacts and structural remains, indicating that the town was not only inhabited but flourished as an urban centre during this time.

Among the items discovered are Satavahana coins, remains of brick houses with rammed clay flooring, ring wells, roof tiles marked with impressions of rice and wheat husk, and planned drainage systems which reveal that it was home to a community who had stable agrarian practices and had their own civic infrastructure.

Other findings in the region include Black-and-Red Ware, Red Polished Ware, amphora fragments, and beads made of semi-precious stones, which suggests a settlement engaged in both regional trade and long-distance exchange. Notably, Scholars such as K.S. Chandra (2019) has suggested that Paunar likely functioned as a transit point within the Satavahana realm. Chandra writes that, “Being under Satavahana dominions, socio-economic relations were at their peak, and Paunar, located at the northeast part of the dominion, must have acted like a buffer between other locations for transit, which is obvious from the rich findings during excavations.”

The Spread of Buddhism and Remains in Pavnar and Dhaga

Pavnar’s location along ancient trade routes appears to have contributed to its emergence as a centre of early Buddhism. Its position along ancient trade routes perhaps made it accessible to travelling merchants and monks and linked it to the wider network of Buddhist centres across the Deccan.

Jason Neelis has observed that early Buddhist monasteries were often located along caravan routes, functioning as both religious institutions and logistical halts. This pattern holds in the case of Paunar and nearby Dhaga. A 2022 field survey by Nishant Zodape recorded fragments of Buddhist sculptures and architectural remnants in these locations.These include sculptural remains and architectural indicators of monastic habitation. Together, they suggest that Wardha district was part of a wider network of Buddhist religious activity in the Deccan from the early historic period onward.

The Gavli Rajas and Early Pastoral Traditions in Hinganghat

Following the decline of the Satavahanas, the historical record becomes sparse. However, local traditions preserved around Hinganghat and Girar refer to the rule of Gavli (herdsmen) rajas. These traditions, recorded in the colonial district Gazetteer (), describe a time when pastoral communities dominated the region.

Some scholars have associated these accounts with the Abhiras, who ruled from Khandesh in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, and were known for their pastoral roots. Archaeological remains like stone barrows and cromlechs, found in adjacent regions like Nagpur, have also been linked—tentatively—to these early groups.

Colonial researchers such as J. Murray Mitchell and V.A. Smith speculated on connections between such communities and migrant Saka groups from Central Asia. While these connections remain uncertain, the persistence of these oral traditions suggests that early pastoral societies may have played a formative role in shaping local power structures before the rise of later dynasties.

Paunar as the Possible Capital of the Vakataka Dynasty

In the 4th century CE, the Vakataka dynasty rose to prominence across Vidarbha. They ruled for over two centuries, establishing a reputation for administrative strength and religious patronage. Wardha district appears to have been particularly important to the dynasty; for, during the reign of Pravarasena II, it is believed that the Vakatakas shifted their capital from Nandivardhan (modern Nagardhan near Nagpur) to a new city named Pravarapura. Archaeological remains, together with the distribution of artefacts from the Vakataka period, have led several scholars, as noted in the district Gazetteer (1974), to identify present-day Paunar as a probable site for this city.

If this identification holds, Paunar’s status during this period would have extended beyond religious and commercial functions to become the political centre of the kingdom. The region’s agricultural wealth, particularly from cotton cultivation (see agriculture for more), likely supported the stability and prosperity of the Vakataka state. Oral traditions and some historical accounts also maintain that a fort was constructed here under Vakataka rule.

Remains attributable to Vakataka period can be found across Paunar. During the building of what is now the Paunar Ashram (see Cultural Sites), stone sculptures were unearthed, carved with scenes from the Ramayan and Mahabharat, some of which are preserved within the ashram’s precincts. Interestingly, based on the style of the sculptures and the site’s location, some scholars have proposed that this may have been the site of a Ram Mandir, which was built under the influence of Prabhavatigupta, the legendary Gupta princess and queen mother to Pravarasena.

Deoli Inscription and the Rashtrakutas in Wardha

After the Vakatakas, Wardha district likely came under the Chalukyas of Badami, who ruled large parts of the Deccan between the 6th and 8th centuries CE. They were followed by the Rashtrakutas, who maintained control until the end of the 11th century.

Notably, traces of Rashtrakuta presence in Wardha comes from a copper-plate inscription found at Deoli, dated 940 CE, during the reign of Krishna III. The grant records a parcel of land awarded to a Kannada-speaking Brahmin, suggesting integration of Wardha into their administrative systems. The boundaries mentioned in the inscription also help identify historical rivers and settlements, including the Kandana/Kanhana, a river that likely corresponds to the Kanhana of Nagpur.

By the beginning of the 12th century, the region could have possibly come under the control of the Paramaras of Malwa. An inscription dated 1104–05 CE, found in the nearby Nagpur district, refers to a Lakshma Deva, believed to be a viceroy under the Paramara king of Malwa. The Paramaras were expanding into Berar, the Godavari basin, and parts of Karnataka during this period.

Later, from around 1187 to 1317 CE, the area fell under the rule of the Yadava dynasty, whose capital was at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad). The Yadavas exercised strong control over the Deccan plateau, including much of present-day Maharashtra.

Medieval Period

The close of the 13th century marked a turning point in the political history of the Deccan. In 1294 CE, Alauddin Khilji, then a general under Sultan Jalaluddin of Delhi, led an expedition into the region, ultimately paving the way for Delhi Sultanate influence over the Berar region. While there is no record of his army directly traversing Wardha, there is material evidence (i.e., his coins found in the district) which indicates some level of administrative or economic influence of the Delhi Sultanate under the Khiljis in the region. These suggest the extension of Delhi's economic or symbolic control, even into peripheral tracts like Wardha.

This brief episode of Delhi’s ascendancy was part of a broader pattern of northern intervention into the Deccan. Yet, the Sultanate’s direct presence in these parts proved short-lived, as more regionally rooted powers rose in its wake.

Offices of Deshmukh and Deshpandia

With the decline of Delhi’s hold over the Deccan, political authority in Berar and the adjoining tracts shifted to regional powers. By the mid-14th century, the Bahmani Sultanate, founded in 1347 CE with its first capital at Gulbarga (Kalaburagi, Karnataka) and later at Bidar (Karnataka), had extended its sway into Berar. The Wardha region, lying within this sphere of influence, appears in records of the time as being administered through the hereditary offices of Deshmukh and Deshpandia.

These offices, noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1906) and by Grant Duff, operated over groups of villages. The Deshmukh (also called Desai or zamindar) served as the territorial head, responsible for general oversight and leadership, while the Deshpandia (also known as Deshlekhak or kanungo) maintained revenue accounts and land records. Their position in relation to a group of villages was comparable to that of the patel and kulkarni within a single village. In return for their services, they held customary rights to a portion of the produce—often one-twentieth of the arable yield—alongside other hereditary privileges.

It is not that the Bahmani’s devised this system of local administration. Some contemporary administrators, such as John Briggs, argued for an earlier, possibly pre-Bahmani origin of these offices, citing their Sanskrit nomenclature and references to similar roles under earlier Hindu rulers. Surviving records, including land-grant confirmations by the kings of Bijapur (present-day Vijayapura, Karnataka) to Desais and Deshpandes, further suggest that these offices were inherited and adapted by successive regimes rather than created anew. However, their persistence in Wardha into the medieval period, in some ways, illustrates the continuity of local administrative structures despite political change.

During the mid-15th century, the region became entangled in conflicts among competing powers. In 1437, the king of Gujarat, aided by the Raja of Gondwana—probably of the Chanda line—launched an invasion of Berar. The Bahmani hold weakened in the following decades, and by 1518 the dynasty had collapsed. In the redistribution of its territories, Berar passed to the Imad Shahi dynasty. The rulers of the dynasty, however, seem to have lacked the military strength needed to secure their borders. This allowed neighbouring powers to press into their territory. To the south-east, the Gond chiefs of Chanda increased their influence, extending their control across the Wardha River into areas that had formerly been part of Berar. It is likely that portions of present-day Wardha district came under Gond authority during this period.

By the latter half of the sixteenth century, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate had taken control of Berar. Their possession, however, was brief. In 1594, Berar was ceded to Emperor Akbar, bringing Wardha for the first time under the authority of the Mughal empire.

The Sarkars of Berar Under the Mughals

Around 1599, five years after its cessation, Berar was organised as a province or in other words a Subah. According to the text Ain-i-Akbari, this Subah was divided into 13 smaller administrative units called Sarkars. Two of these Sarkars, and part of a third, were located beyond the Wardha River. However, large parts of this region were still controlled by the Gond chiefs and yielded no revenue to the Mughal State.

The lands of present-day Wardha district were apportioned between three of these Sarkars, namely, Kherla, Gawilgarh, and Paunar:

- Kherla Sarkar (named after the Gond fort of Kherla near Betul, Madhya Pradesh) included the Waigaon tract of Wardha.

- Gawilgarh Sarkar included places like Ashti, Anji, and Karanja-Wadhona.

- The Paunar Sarkar, named after the town of Paunar in the district, covered most of present-day Wardha, including areas like Paunar, Sewanbarha, Selu, Keljhar, and Mandgaon.

During Akbar’s reign, the Ain-i-Akbari recorded the estimated revenue from the parganas (administrative units) which covered the Wardha area to be 2 crore 51 lakh dams. With 40 dams equalling one rupee, this amounted to roughly 6,30,000 rupees in the coinage of the period. W. W. Hunter, writing in the 19th century, calculated this to be equivalent to about nine lakhs in his time.

Under Akbar’s revenue arrangements, one-third of the total agricultural produce was taken as the state’s share. The recorded figures therefore point to a well-cultivated and prosperous tract, indicating that Wardha, under Mughal administration, possessed a flourishing agrarian economy.

Pratap Rao and the Marathas

By the late 17th century, the Mughal Empire’s hold over the Deccan was weakening, and new forces were emerging in Berar — notably the Marathas, alongside the Gonds and the Nizams. From 1670 onwards, Maratha incursions into the region became frequent. In 1671, Shivaji’s general Pratap Rao reached Karanja (present-day Washim district) and is believed to have compelled village headmen, including those in what is now Wardha district, to pay chauth (a form of tribute).

In 1704, the Mughal general Zulfikar Khan temporarily checked these advances, but the Marathas soon resumed collecting chauth and sirdeshmukhi (an additional levy). These extractions reduced local revenue available to the Mughal administration and steadily undermined their authority in Berar.

The Gond Kingdoms of East Vidarbha

Other regional powers also began to assert themselves more forcefully. Among these were the Gond rulers of eastern Vidarbha, who controlled extensive forested and agrarian tracts beyond the Wardha River. Two Gond polities had emerged here — the Gond House of Chandrapur (see Chandrapur district) and the Gond House of Deogarh (present-day Deogarh, Madhya Pradesh). Both rulers had traditionally paid tribute to the Mughal emperor through an officer stationed near present-day Nagpur, under the faujdar of Paunar (Wardha district).

During Aurangzeb’s later years, however, due to prolonged wars, Bakht Buland (See Nagpur district for more), the Raja of Deogarh, began plundering Berar and expanding his control over areas that were previously under Mughal administration, such as those which lay in areas south and west of Nagpur. His successor, Chand Sultan, shifted the capital to Nagpur, bringing southern Wardha within his dominion. This period saw the rise of an independent Gond kingdom centred on Nagpur.

However, the northern parts of Wardha, such as Ashti and its surroundings, remained in Berar, which had by then come under do-amli or joint administration between the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad.

After 1724, Berar was formally placed under the Nizam of Hyderabad following the declaration of independence by Asaf Jah I — later titled Nizam-ul-Mulk — from the Mughal Empire. In practice, however, Maratha influence was already entrenched across much of the province, including Wardha. Even in areas where the Nizam appointed officials, Maratha representatives often operated in parallel, collecting their dues and, in some cases, displacing the Nizam’s men entirely.

The revenue division during this do-amli (joint) arrangement was heavily weighted in the Marathas’ favour. Typically, they claimed about 60 per cent of total collections:

- 25% as chauth

- 10% as sirdeshmukhi

- 25% as an administrative allowance (faujdar’s share)

The remainder went to the Nizam’s treasury. In southern Wardha, the Gond rulers of Nagpur still held sway during Chand Sultan’s reign (d. 1739), but their political position later would increasingly be influenced by Maratha power.

Raghuji I Bhosale

The Deorgarh kingdom which was now based in Nagpur persisted under Chand Sultan until his death in 1739, when a disputed succession invited outside intervention. Raghuji Bhosale, a Maratha leader authorised to collect chauth in Berar and Gondwana on behalf of the Peshwa, entered the capital under the pretext of restoring order. By 1743 he had reduced the Gond ruler to a figurehead and assumed the reins of government, thus bringing most of present-day Wardha within the Nagpur State.

Under Raghuji and his immediate successors, the Bhosales were noted for their closeness to the cultivating classes and their practical administration. Village headmen retained certain judicial functions, revenue officers handled disputes, and the general policy was to encourage agriculture. The closing decades of the eighteenth century, particularly under Raghuji Bhosale II, marked a period of prosperity.

The opening years of the nineteenth century, however, saw the intrusion of British power. In 1803, during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, Raghuji II Bhosale was drawn into hostilities against the East India Company. The British advanced into Berar and Gondwana, defeating the Bhosale forces in two engagements of note — first at the hill-fort of Gavilgad in present Amravati district, and then at Adgaon in Nashik district. These reverses compelled the Raja to sign the Treaty of Deogaon, under which all territory lying to the west of the Wardha River was ceded to the Company. From this time, the present district lay divided: its western tract under British administration, and the remainder still held by the Nagpur State.

In 1817, the Third Anglo-Maratha War brought renewed British intervention. Raghuji II’s successor was drawn into the Peshwa’s conflict with the Company, and in early 1818 British forces entered Nagpur. The ensuing subsidiary alliance reduced the Bhosale ruler to the position of a dependent prince. The kingdom, including Wardha, remained nominally in his possession, but a British Resident was stationed at Nagpur, and a Commissioner, under the Governor-General’s authority, supervised its administration.

This arrangement endured until 1830, when the young ruler Raghuji III was formally invested with the government. His reign passed without major conflict, but he died in December 1853 without a male heir. Applying the Doctrine of Lapse, Lord Dalhousie’s government annexed the State. Nagpur and its territories, Wardha among them, were incorporated into the British dominions as the Nagpur Province, placed under the charge of a Commissioner at Nagpur.

Colonial Period

First War of Independence, 1857

The annexation of Nagpur in 1853, carried out under the doctrine of lapse, had unsettled the political balance of the region. In Wardha and the adjoining tracts, the removal of the Bhosale rulers meant the dismantling of familiar administrative networks and the growing presence of new colonial structures. Tensions simmered throughout the years along with discontent which was felt by many.

By 1857, news of uprisings in north India spread rapidly along trade and communication routes, finding ready listeners in the towns and villages of Berar and Vidarbha. In Nagpur, close to Wardha, sympathy for the rebels was not confined to the common people; members of the former royal household also extended quiet support. The district Gazetteer (1906) notes that Baka Bai, the regent princess of the Bhosale family, was among those who encouraged anti-colonial activity in both Nagpur and Wardha.

The following year, events to the north gave renewed hope to those opposing British authority. In late 1858, Tatya Tope — a key leader of the 1857 struggle and long associated with the Maratha cause — crossed the Narmada River in an attempt to move into the territories of Berar and the wider Deccan. His reputation as a seasoned commander who had fought in Kanpur (Uttar Pradesh) and other major theatres preceded him. His presence alarmed British officials, who feared that a leader so closely linked to the Peshwa might incite rebellion among the local population.

Formation of the Wardha district

The suppression of the revolt led to a major reorganisation of British India’s political structure. In 1858, authority was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown. One of the early measures under this arrangement was the reorganisation of provincial boundaries to strengthen control over distant and scattered territories.

In the wider Nagpur region, the districts lay at some distance from any local seat of government, and communication with them was slow and uncertain. The difficulty of exercising effective supervision over these tracts, combined with the unsettled conditions of the preceding years, made it necessary to revise the existing arrangements.

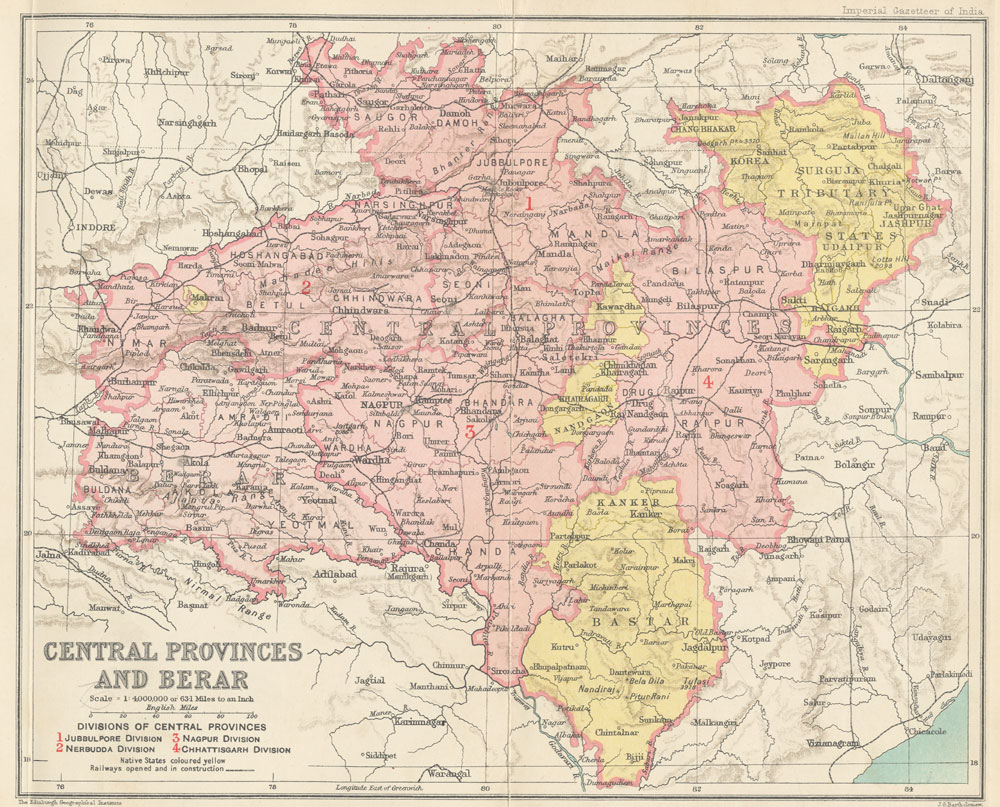

In 1861, the Central Provinces and Berar were formed, and many territories, including the area now comprising Wardha was brought under a single provincial administration. At that time Wardha remained a part of the Nagpur district, but the extent of that district, coupled with the growing importance of the Wardha valley as a cotton-producing tract, led to a further change.

Accordingly, in 1862 Wardha was constituted a separate district. Kaotha, near Pulgaon, was selected as the headquarters, but in 1866 the site was transferred to a new town laid out at Wardha. This settlement was planned upon the site of the village of Palakwadi, which was absorbed in the process, and has since remained the administrative centre of the district.

Wardha Town

The present town of Wardha owes its origin much to this transfer of the district headquarters from Kaotha in 1866. The site selected, as mentioned above, was that of the village of Palakwadi, which was cleared to make way for a new administrative settlement. The planning and construction were carried out under the supervision of Sir Bachelor and Sir Reginald Craddock, in accordance with the principles of colonial town-planning. Broad roads were laid out in a regular grid, with the principal administrative offices and civic buildings occupying prominent positions.

During the British period, several institutions and thoroughfares bore the names of these officials. The principal school of the district was known as the Craddock School, and one of the main roads carried Sir Bachelor’s name. In the years following Independence, many of these were renamed — the Craddock School becoming the Mahatma Gandhi School, and King George Hospital receiving a new designation. In some cases, the original name-stones remained in place, concealed beneath later additions.

A number of public buildings of the colonial period are still standing. Among these are the old Zila Parishad building, the Central Jail, the church at Bajajwadi, and the Christian cemetery, each representing a phase in the administrative and social organisation of the district during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Pulgaon

Among the other settlements to develop in this period was Pulgaon, which was constituted as a municipality in 1901. The older quarter, lying to the south of the railway station, is believed to have grown from housing provided for labourers engaged in the construction of the nearby railway bridge over the Wardha river, and came to be informally referred to as “Bridgetown.”

Close to Pulgaon lies the Central Ammunition Depot, now the second-largest of its kind in Asia. For much of its existence, the area was open to limited public access. From about 1999–2000, and particularly after the events of 11 September 2001 and the attack on the Indian Parliament later that year, security measures were greatly tightened, and recreational access was withdrawn.

Cotton Production

The growth of Wardha and its urban planning, in many ways, coincided with the transformation of the district’s agriculture. In the valleys and uplands around Hinganghat, Arvi, and Pulgaon, cotton had long been grown for local use, but the extension of railways and the opening of new markets in the latter half of the 19th century brought the crop into the centre of the district’s economy.

The colonial district Gazetteer (1906) records the rapid spread of cotton cultivation in this period. In 1867, 1,84,000 acres in Wardha were under cotton. By the time of settlement in 1892–94, this had risen to 251,000 acres, and by 1904–05 the figure stood at 4,04,000 acres — more than double the area within forty years; this sharp rise indicating how important cotton had become in the district’s agrarian economy under colonial rule.

Local farmers cultivated multiple varieties like jari and bani, each having its own distinct qualities. The bani produced in Hinganghat was especially prized and marketed as “Hinganghat cotton,” giving the area a notable place in cotton markets.

In 1887, an experiment was made to diversify cultivation with the introduction of a foreign strain — Upland Georgian — in the Arvi region. Its pink to scarlet flowers stood out among the pale blooms of local fields, but its lint was considered inferior, its seeds germinated poorly, and the yield was unsatisfactory. It was recorded in the Gazetteer (1906), farmers, accustomed to the reliability of jari and bani, declined to adopt it. Owing to these reasons, its distribution was halted until it could be adapted to local soil and climate.

By the early twentieth century, cotton was firmly established as the dominant crop in Wardha district. The expansion of cultivation also supported associated activities such as ginning and pressing. In later decades, the district’s cotton fields would supply both industrial mills and hand-spinning units.

In the mid-nineteenth century, cotton itself in Wardha would acquire a new significance through its association with Mahatma Gandhi. His ashram at Sevagram would make the district a centre for khadi production. Cotton from the surrounding villages would be spun on the charkha, linking cultivation directly with the ideals of Gandhi and rural industry. The connection between cotton and Wardha, in many ways, endures even today as its cotton yarn is now recognised under the “One District One Product” scheme.

Wardha Valley Coal Mine

Coal mining, too, was beginning to make its mark on the regional economy during this period. The colonial district Gazetteer (1906), described the coalfield in Wardha as stretching “for a long distance in the vicinity of the Wardha, Pranhita, and Godavari rivers.” At that time, the principal working was the Government colliery at Warora (present-day Chandrapur district), while new seams were being opened in other parts of the coalfield.

In later decades, the Wardha Valley Coalfield (covering parts of present-day Chandrapur, Yavatmal, and Wardha districts) became one of the major coal-producing regions in India. According to the Geological Survey of India, it holds over 5,300 million tonnes of coal, which is used mainly for power generation.

Laxminarayan Mandir and the Temple Entry Movement

The early years of the twentieth century also saw the growth of institutions which were to play a part in the social awakening of the district. In 1905, Seth Bachhrajji Bajaj, a wealthy merchant already well-known in the region, built the Laxminarayan Mandir. At the time, entry into such mandirs was largely restricted by caste. More than twenty years later, in 1928, this Mandir became the focus of reformist action when Acharya Vinoba Bhave, with the support of Jamnalal Bajaj, led a group of Dalit worshippers inside. The event was intended as a direct challenge to prevailing social barriers and was among the earliest recorded temple-entry actions in the district.

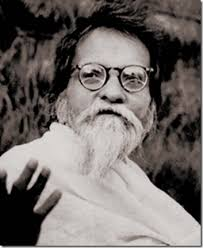

Baba Amte

Baba Amte, revered as a modern Gandhian saint, made a monumental contribution to humanity by dedicating his life to the service and empowerment of people afflicted with leprosy. He was born as Murlidhar Devidas Amte on December 26, 1914, in Hinganghat (Wardha district) to a wealthy land-owning family. He moved to Chandrapur and founded Anandwan ("Forest of Joy") Ashram in 1949. He passed away in Anandwan in 2008.

Vinoba Bhave and the Paramdham Ashram

Vinoba Bhave’s connection with Wardha only deepened in the following decade. A social reformer and close associate of Mahatma Gandhi, Vinoba Bhave’s association with Wardha began in 1916, when he joined Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement and later made frequent visits to the district.

In the early 1930s, Jamnalal Bajaj, a leading industrialist and nationalist based in Wardha, invited Bhave to Paunar, a village on the banks of the Dham River. Bajaj had earlier developed the site as a seasonal retreat. Under Bhave’s guidance, it was transformed into the Paramdham Ashram, which became his permanent base. From here, he conducted training in satyagraha, promoted constructive village industries, and encouraged self-sufficiency among rural communities. The ashram came to be known as a place where religious practice and social reform were pursued together.

From Pavnar, Bhave launched the Bhoodan Movement in 1951, where he walked to villages across India to persuade landowners to voluntarily donate part of their holdings to the landless. The ashram functioned as the organisational headquarters of this campaign, coordinating the collection of records and correspondence related to land donations.

Another one of his most enduring outcomes at Paunar was the establishment of the Brahma Vidya Mandir in 1959. Run by women from across the country, the centre functions as a residential space for spiritual study, communal life, and rishi kheti (a form of non-violent, chemical-free agriculture.) The ashram remains active, continuing these practices today.

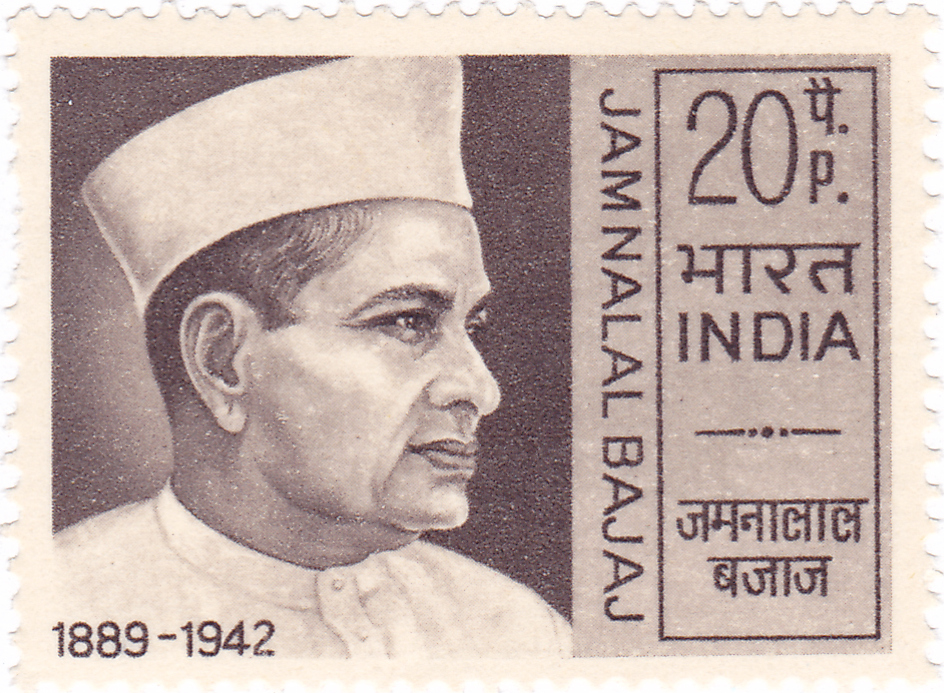

Seth Jamnalal Bajaj

The philanthropic and political atmosphere that made such initiatives possible in Wardha owed much to Jamnalal Bajaj. Born in 1889 at Kashi-ka-Bas, near Sikar in the Jaipur State, he was adopted at the age of five by Seth Bachhrajji Bajaj, a merchant of Wardha, and brought to that town. In the years following, he established himself as a successful trader and businessman (who notably founded the Bajaj Group). His activities, however, soon extended beyond commerce into public causes of wider scope.

During the First World War, Bajaj contributed generously to the British war effort, for which he was endowed with the title of Rai Bahadur and an honorary magistracy. The close of the war, however, brought a change in his political convictions. The temper of the country was shifting, and by 1921 Bajaj, drawn to the principles of Mahatma Gandhi, renounced both honour and office in protest against imperial policy. The acquaintance between the two men deepened into friendship, and it was through Bajaj’s persuasion and patronage that Gandhi was encouraged to make Wardha the base of his later work. The land on which Gandhi’s ashram stands was Bajaj’s gift.

Mahatma Gandhi and the Sevagram Ashram

Mahatma Gandhi’s connection with Wardha arose from a series of events in the 1930s. In 1930, at the outset of the Salt Satyagraha, he left the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad (Gujarat), declaring that he would not return there until India had achieved independence. The years that followed were taken up with travel to different provinces, intervals of imprisonment, and work in rural areas. By 1935 he was seeking a more central location from which to conduct his activities, one removed from the larger towns yet in keeping with his preference for village life and his belief that India’s future rested on the self-reliant village community.

It was at this stage that Seth Jamnalal Bajaj, a close associate and supporter, offered land in a village near Wardha. The site, then known as Shegaon, lay eight km south-east of the town and was surrounded by fields of cotton and grain. Gandhi arrived in April 1936, when he was sixty-seven years of age, and decided to settle there. He renamed the place Sevagram which means the “village of service,” and had a small group of huts built in the local style, mud walls, thatched roofs, and simple furnishings. One hut was occupied by Gandhi and his wife Kasturba; others housed companions and visiting co-workers.

From Sevagram he continued both his political work and his programmes for rural reconstruction. Discussions held here ranged over village industries, sanitation, education, and social reform, as well as the direction of the independence movement. The annual session of the Indian National Congress, convened in Wardha in 1934, had already brought national attention to the district, and the ashram became a regular meeting place for leaders from across the country. Gandhi remained at Sevagram until 1948, and the village has since retained its association with the later phase of his life.

Magan Sangrahalaya

Among Gandhi’s undertakings at Sevagram was the founding, in 1938, of the Magan Sangrahalaya. Conceived as a memorial to his associate Maganlal Gandhi, the institution was devoted to the demonstration of rural industries and village crafts. Its exhibits ranged from improved ploughs and dairy apparatus to diverse designs of the charkha, from khadi cloth to the handiwork of village artisans. In harmony with the ideals of the Swadeshi movement, the Sangrahalaya served as a center to spread awareness about the research and development of rural industries, agriculture, dairy, various types of charkhas, khadi, handicrafts by rural artisans.

Vishwa Shanti Stupa

The district’s association with Gandhian ideals also drew international figures. Among them was the Japanese Buddhist monk Nichidatsu Fujii, founder of the Nipponzan-Myōhōji order, who met Gandhi at Wardha in 1933. United by their commitment to non-violence, Gandhi incorporated the chanting of daimoku—the title of the Lotus Sutra—into the ashram’s prayers during Fujii’s stay. After the Second World War, Fujii began building Peace Pagodas around the world to promote harmony. The Vishwa Shanti Stupa at Wardha forms part of this series, linking the district’s modern history with a wider global movement for peace.

Wardha Congress Working Committee, 1942

Wardha also became a stage for decisive political action. On 14 July 1942, the Congress Working Committee met here to consider its response to the failure of the Cripps Mission and the ongoing war. The result was the Quit India resolution which called for the immediate withdrawal of British power.

Within weeks, Gandhi’s “Do or Die” call had been taken up across the district. Strikes, processions, and demonstrations followed, joined by students, workers, and farmers alike. The British response was swift and severe, with mass arrests and the use of force to suppress gatherings. Yet the movement endured for more than a year, leaving a clear record of the district’s place in the final struggle for independence.

Post-Independence Era

After India achieved independence in 1947, Wardha, then part of the Central Provinces and Berar, underwent several administrative changes. In 1950, it was included in the newly formed state of Madhya Pradesh. However, this arrangement changed with the enactment of the States Reorganisation Act in 1956, which redrew state boundaries along linguistic lines. As a result, Wardha was transferred to Bombay State. Later, in 1960, when Bombay State was divided, Wardha became part of the newly formed state of Maharashtra.

Sources

A.R. Kulkarni. 1969.The origin of Deshmukh and Deshpande.Vol. 31. The Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.

Abu Fazl. 1873. The Ain-I-Akbari.Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Anjali Marar. 2023. Pune student’s accidental discovery: 2,600-yr-old megalithic site in Wardha. Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pun…

Bamb, O. P. 2022. “Changing Memories of Monuments: Case Study of Khairwada Megalithic Circles Wardha District, Maharashtra.” ASSSR.https://www.academia.edu/121927537/Changing_…

Bamb, O.P. 2022. “Newly Discovered Yesamba Megalithic Circles, Wardha District, Maharashtra and Memories of the Monument.” Journal of History, Archaeology and Architecture.Vol. 1, no. 2.https://www.pbjournals.com/image/catalog/Jou…

Central Mine Planning & Design Institute. 2021.Proposal for preliminary exploration (G-3 stage) for coal: West of Borda & Ghonsa–Parsoda, Wardha Valley Coalfield, District–Yavatmal, Maharashtra. CMPDI.https://nmet.gov.in/upload/project_registrat…

D.C. Ahir. 2009. The Pioneers of Buddhist Revival in India. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications Klaus Schlichtmann. Japan in the World: Shidehara Kijuro, Pacifism, and the Abolition of War. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Debala Mitra. 1984. Indian Archaeology 1981-82 - A Review. Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi.

Dennis Dalton. 1977. Reviewed Work: Harijan: Collected Issues of Gandhi's Journal, 1933-1955 (19 vols.). by Mohandas Gandhi. The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 570–72.https://www.jstor.org/stable/2054131?seq=2

Dr. Iravati Karwe. 1968. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Maharashtra Land and its People.

Government of Maharashtra. 1974.Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Wardha District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary and Publications.

Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation. n.d. https://www.jamnalalbajajfoundation.org/ward…

Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation. n.d. Gitai Mandir.Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation.https://www.jamnalalbajajfoundation.org/ward…

Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation. n.d. Paunar Ashram. Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation.https://www.jamnalalbajajfoundation.org/ward…

Jason Neelis. n.d. Buddhism on the Silk Road.https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibi…

K.S. Chandra. 2019.A comparative study of material culture found from excavations at Bhokardan and Paunar. In Human and Heritage: An Archaeological Spectrum of Asiatic Countries (Felicitation to Professor Ajit Kumar), Volume I. New Bhartiya Book Corporation, New Delhi.

Kant, Rajni, and Balram Bhargava. 2019. “Medical Legacy of Gandhi: Demystifying Human Diseases.” The Indian journal of medical research. Vol. 149.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC651…

Kumar Amarendra Singh. 1985. “Some Aspects of Agrarian History under the Vakatakas.” Vol 46. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141346?seq=1

Nanda, B. R. 2002. In Gandhi’s Footsteps: The Life and Times of Jamnalal Bajaj. Oxford University Press. Chapter 17: Gandhi Comes to Wardha, pp. 210–223.https://academic.oup.com/book/10270/chapter-…

Nishant Zodape. 2022. Archaeological remains of Buddhism at Early Historic Vidarbha (Maharashtra).Vol I, Issue III, Amoghvarta.

P. K. Thomas. 1993. Subsistence and Burial Practices Based on Animal Remains at Khairwada. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute.

R.V Russel. 1906.Central Provinces District Gazetteer: Wardha District, Vol A, Descriptive. Pioneer Press. Allahabad.

Shantanu Vaidya. 2016. Burials and Settlements of the Early Iron Age in Vidarbha: A Fresh Analysis, Man and Environment.Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies.

Shree Siddhivinayak Kelzar Temple. n.d.https://www.shreesiddhivinayakkelzar.com/

Tilok Thakuria. 2017.Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective.Vol. 5, Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology.

Vinoba.in. n.d. Life of Vinoba Bhave. Vinoba.in.https://vinoba.in/life

Websites Referred:The Gandhi Ashram, Sevagram (Official website). Wardha district: Official website, Wikipedia.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.