Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Washim as a Tirtha Kshetra and Centre of Learning

- Early Political Developments and Dynastic Control

- Capital of the Vatsagulma Branch of the Vakatakas

- Harisena and the Mysterious Decline of the Vatsagulma Branch

- Madhyameshwar Mandir and Washim’s Place in Ancient Astronomy

- Medieval Period

- Bahmani Sultanate & Administrative Reorganization

- Mughal Administration and Regional Reorganisation

- The Development of Shahpur in Buldhana

- Marathas

- Washim’s Role as a Military Encampment and the Treaty of Kanakpur

- Balaji Mandir

- Washim’s Agricultural Wealth and Revenue Significance

- Battle of Adgaon (1803) and Its Aftermath

- Pindari Raids and Disruption (1809)

- Colonial Period

- Washim’s Brief Tenure as a District

- Severe Drought in 1916 and Raghoji Bhagat

- Post-Independence

- Sources

WASHIM

History

Last updated on 28 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Washim is a district in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra, held considerable significance in ancient times. Scholars generally associate the present-day district with the ancient settlement called Vatsagulma, which is mentioned in early Indian texts as a place closely connected to several rishis. This identification is further supported by its location within Dandakaranya, the expansive forest tract that features prominently in epic and classical literature. Local traditions alongside scattered remains, additionally, point to its place as a centre of learning and tirthayatra (pilgrimage) in the early centuries.

In the 4th and 5th centuries CE, Washim gained political stature as the capital of a branch of the Vakataka dynasty, a major power in the Deccan. Its prominence continued under successive regimes, eventually becoming part of Berar Province under British administration, governed through nearby Akola. In 1998, Washim was formally separated from Akola and established as a separate district.

Etymology

The name Washim is generally understood to come from the ancient settlement known as Vatsagulma. This name appears in many ancient Indian texts, such as the Padma Purana, and is closely tied to stories about a Rishi named Vatsa. He is said to have performed penance in this region with such intensity that it disturbed the natural order, prompting the Devtas and Devis to descend and gather near his hermitage. This divine assembly gave the place its name, Vatsa-gulma, meaning “the gathering of Vatsa.”

References to Vatsagulma can also be found in epic texts like the Mahabharat, indicating the region’s long cultural significance. The continuity of this name into the early medieval period can be evidenced by the writings of Rajashekhara, a Sanskrit poet and dramatist who wrote in the 9th and 10th centuries. In his treatise Kavyamimamsa, he mentions Vatsagulma to be within the bounds of Vidarbha region, and his play Karpuramunjari, composed under the patronage of the Gurjara-Pratiharas at Kanauj, likewise refers to it as a part of the Dakshinapath.

The present name Washim is regarded to be a later linguistic development and believed to be a corrupt form of Vachchhoma, the Prakrit version of Vatsagulma. The transformation is traced as follows, Vatsagulma (वत्सगुल्म) → Vachchhoma (वछ्छोम) → Vashoma (वशोम) → Washim (वाशिम).

Another tradition holds that a ruler named Vasuki established a settlement in this area and named it Vasuki Nagar. Over the centuries, the name gradually changed, first to Bashim, and later to Washim, as it is known today.

Ancient Period

Over the course of history, the region now forming Washim district has fallen under the influence of many different political and cultural powers. Little is currently known about its early history, however, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These are better understood when placed in the context of Vidarbha, Berar, and Akola, to which Washim has for long remained connected by politics, geography, and culture.

Washim as a Tirtha Kshetra and Centre of Learning

Washim has long been regarded as a site of religious and intellectual significance. Ancient textual sources, notably the Padma Purana, refer to the site as Vatsagulma, where sages are said to have undertaken penance and engaged in the transmission of spiritual knowledge. Among these, the figure of Vatsa Rishi features prominently; his presence is believed to have sanctified the area and contributed to its identification as a tirtha kshetra.

The Akola district Gazetteer (1977) also mentions that Washim was once believed to have 108 tirthas. Interestingly, it is said that each tirtha was linked to a Rishi. While many of these sites are no longer visible, their names and associations persist in local oral traditions. One of the most prominent of these is Padmatirtha, a sacred lake and temple complex located in Deopeth, within Washim. The site is described in the Gazetteer as “one of the chief tirthas created by Vishnu.” Local belief holds that the lake was formed when Vishnu placed a lotus (padma) at this spot during his search for Garuda.

Padmatirtha is further connected with the Rishi Dadhichi, known in Vedic literature for offering his bones to the Devis and Devtas for the forging of the divine weapon Vajra. It is believed that his remains were immersed in the waters of the lake.

Even in later centuries, the area remained important. Ramdevrao Yadav, a ruler of the Seuna Yadava dynasty in the 12th century, is believed to have visited Padmatirtha for ritual bathing. At the time, there were ten stone-paved ghats around the lake, and its waters were thought to purify not just the living, but even the ashes of the dead. Many devotees, drawn by these enduring associations, continue to visit Padmatirtha for ritual bathing and darshan.

Early Political Developments and Dynastic Control

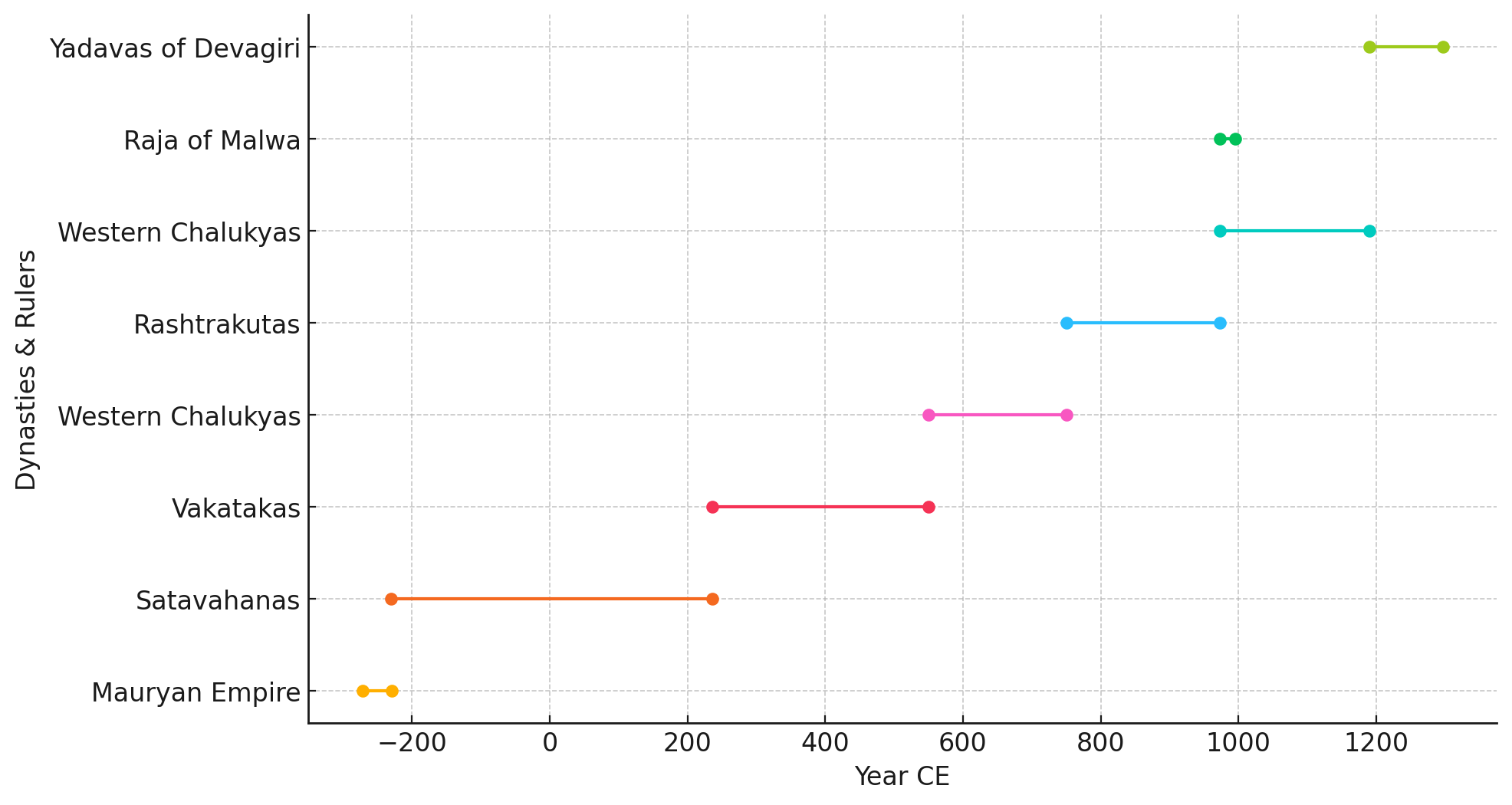

The early political history of Washim likely mirrors the broader developments in the Berar region. During the 3rd century BCE, the area is believed to have formed part of the Mauryan Empire under Emperor Ashoka, whose edicts and administrative reach extended into the Deccan. Following the decline of Mauryan control, the region likely came under the influence of various smaller powers between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE. These included Indo-Scythian (Saka), Pahlava, and possibly Yavana rulers, among them the Saka Satrap Rudradaman I, whose inscriptions reference areas in western India that may have extended influence eastward.

By the 2nd century CE, the Satavahana dynasty, particularly under Pulumayi II, is believed to have controlled portions of southern Berar, which likely included present-day Washim.

Capital of the Vatsagulma Branch of the Vakatakas

A significant phase in Washim’s history unfolded between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE, when it became the capital of the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakataka dynasty. The Vatsagulma branch held a strategically important territory stretching from the Sahyadri mountain range (a mountain range covering the present state of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujarat) to the Godavari River (its source lies in Trimbakeshwar in Nashik). The area under their control included much of present-day Vidarbha and neighbouring parts of the Deccan. Under their rule, the region flourished politically and culturally. Notably, the Vakatakas were patrons of the Ajanta Caves, whose Buddhist murals and architecture are considered masterpieces of early Indian art.

The Vatsagulma branch was established by Sarvasena I, grandson of Vindhyashakti I, the founder of the Vakataka dynasty. Around the mid-4th century CE, Sarvasena I founded a separate line of rule with its capital at Vatsagulma—identified with modern-day Washim. This marked a significant reorganisation within the Vakataka polity. While the main branch ruled from Nandivardhana (near present-day Nagpur), Sarvasena I established a second seat of power to the southwest.

The rulers of the Vatsagulma branch, as identified from inscriptional sources, include:

- Sarvasena I (c. 325–355 CE): Founder of the Vatsagulma branch and established the capital at Washim.

- Vindhyasena (c. 355–400 CE)

- Pravarasena II (c. 400–415 CE)

- Sarvasena II (c. 415–455 CE)

- Devasena (c. 455–480 CE)

- Harisena (c. 480–510 CE): The most prominent ruler of the branch, known for territorial expansion and patronage of the Ajanta Caves.

The existence of the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakataka dynasty remained uncertain until the early 20th century, when key inscriptions were discovered in Washim district. These records helped establish the genealogy, administrative reach, and chronological framework of this lesser-known line of Vakataka rulers.

The first major breakthrough came in 1939, with the discovery of copperplate inscriptions at Washim. These plates provided names of Vatsagulma rulers, beginning with Sarvasena I, and helped confirm the region's role as a secondary seat of Vakataka power alongside the main line at Nandivardhana.

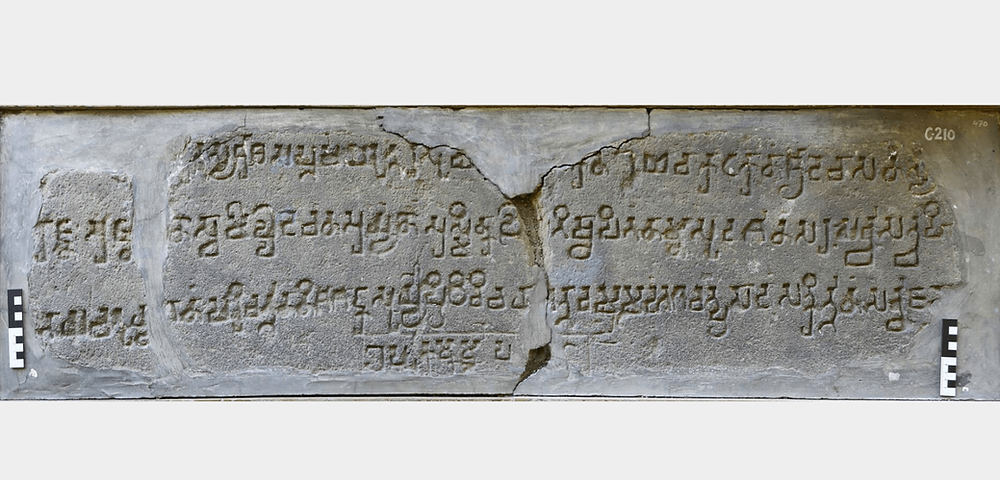

Further clarity emerged in 1963–64, when archaeologist Shobhana Gokhale uncovered a stone inscription near Hisse-Borala village, approximately 10 kilometres south of Washim. The inscription was found embedded in the riverbed of the Vatsagulma river, adjacent to an ancient brick structure known locally as a palu or lake embankment. The artifact was later transferred to the Central Museum, Nagpur, where it remains preserved.

The Hisse-Borala inscription is of particular historical importance because it contains a Saka-era date, offering one of the few fixed chronological points for the Vakataka dynasty. It also mentions a noble named Svamideva, who is referenced in other Vakataka land grants discovered at Thalner (on the Tapi River) and Bidar (in present-day Karnataka). These references span the reigns of Sarvasena II, Devasena, and Harisena, helping historians reconstruct the genealogy and extent of the Vatsagulma branch with greater precision.

For many years, the Hisse-Borala record has been regarded as one of the most important sources for understanding the chronological sequence and territorial reach of the Western Vakatakas.

Harisena and the Mysterious Decline of the Vatsagulma Branch

Harisena, who ruled in the late 5th to early 6th century CE, is regarded as the most distinguished ruler of the Vatsagulma branch. Under his leadership, the kingdom reached its widest territorial extent, stretching from the Tapi River in the north to regions of present-day Telangana in the south.

He is best known for his patronage of Buddhist architecture and painting, particularly the later phase of work at the Ajanta Caves. Inscriptions found in Cave 16 at Ajanta identify him as the principal royal patron. Art historian Dr. Walter Spink, who studied Ajanta extensively, noted that Harisena’s court supported an artistic output that, in his words, “hardly had a rival in the world in terms of its political or artistic achievements.”

Alongside his cultural patronage, Harisena is credited with military conquests and the strengthening of Vakataka rule across the Deccan. However, following his death, the dynasty appears to have declined abruptly. The precise reasons remain uncertain, and no clear records survive detailing the end of Vakataka authority in Vatsagulma.

After the decline of the Vakatakas, in line with the broader patterns in the Deccan and wider Berar region, the region of Washim likely came under the control of the Early Chalukyas of Badami around the mid-6th century CE. These Chalukyas established their dominance across the Deccan, including Berar, and ruled until the mid-8th century.

In the second half of the 8th century, the Chalukyas were overthrown by the Rashtrakutas, led by Dantidurga. The Rashtrakutas became the dominant power in the region and ruled for over two centuries, bringing Berar and Washim under firm control.

Around 973 CE, the Rashtrakutas were defeated by Tailapa II, who revived Chalukya power by founding the Western Chalukya dynasty, also known as the Chalukyas of Kalyani. These rulers reasserted authority over Berar and retained it until the late 12th century. Washim remained under their control until it eventually passed into the hands of the Yadavas of Devagiri.

Madhyameshwar Mandir and Washim’s Place in Ancient Astronomy

In addition to its religious and administrative history, Washim is also noted in several medieval Sanskrit texts for its role in early Indian astronomical geography. These references place Washim, or more specifically Vatsagulma, along a conceptual north–south meridian known as the Madhyarekha, or "central line," used in astronomical calculations.

The Madhyarekha was a theoretical line employed by Indian astronomers to assist in determining the position of celestial bodies, calculating regional time differences, and defining relative distances between locations. It was described as extending from Lanka (Sri Lanka) in the south to Mount Meru in the north, passing through major centres such as Ujjain, Kurukshetra, and, in some accounts, Sri Vatsagulma. This line functioned much like the Prime Meridian at Greenwich does today, serving as a fixed central reference for time and spatial measurement.

One of the earliest references comes from Shripati, an 11th-century astronomer and mathematician, who listed Sri Vatsagulma among several key places situated along this central meridian. In the 12th century, Bhaskaracharya further developed this framework in his work Siddhānta Shiromani, a foundational text in Indian mathematical astronomy. In it, he outlines how time should be adjusted based on a region’s position relative to the central meridian i.e. by “Subtract [ing] time to the east of the meridian, and add to the west.”

This approach provided a practical system for measuring deshantara, or longitudinal time difference, across various parts of the Indian subcontinent.

In Washim today, a Mandir known as Madhyameshwar ("Lord of the Centre") reflects this historical association. Local tradition holds that the site marks the passage of the Madhyarekha. The current structure was rebuilt in 1969, but remains of an earlier basalt construction are visible nearby, suggesting that the site was in use during earlier periods, possibly during the Chalukya rule. The Mandir houses a Shiva linga and is mentioned in the Vatsagulma Mahatmya, a local text that refers to Washim's religious and symbolic significance.

Medieval Period

In the medieval era, the history of the district is shrouded due to limited historical records. However, a few records provides a glimpse into the district’s historical transformation During this time, various ruling entities engaged in a fierce competition for control over the Deccan region, all seeking to demonstrate their dominance and power.

In 1298, Alauddin Khilji, then general under Sultan Jalaluddin and later Sultan himself, led the Delhi Sultanate’s first expedition into the Deccan. At this time, the region that now forms Washim district was part of the Yadava kingdom ruled from Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad). King Ramachandra Yadava faced defeat in 1308, and by 1311, the Sultanate had annexed much of the Yadava territory.

While Washim likely remained under local chieftains or semi-independent rulers during this transitional period, it would have felt the broader political shifts as Delhi established its presence in the Deccan.

Bahmani Sultanate & Administrative Reorganization

From 1312 to 1347, the Deccan was governed by officials dispatched by the Delhi Sultanate and stationed in Devagiri (present Daulatabad). However, in 1347, the Delhi Sultanate's hold on the Deccan began to wane and the Bahmani Sultanate was established in 1347 under Alauddin Bahman Shah. Subsequently, the Bahmani Sultanate divided the Deccan into five provinces, one of which was Berar, encompassing the Washim region. This political reorganization was a significant development, starting a new chapter in Washim’s history.

In 1366, during the reign of Muhammad Shah I Bahmani, the second ruler of the Bahmani Sultanate, a notable episode of political unrest occurred in the Deccan, with reverberations likely felt across the wider Berar region, including the area now comprising Washim district. At the time, the Sultan was engaged in military conflict with the Vijayanagara Empire, which may have stretched the administrative capacity of the state.

Amidst this backdrop, Bahram Khan Mazandarani, who served as deputy governor of Daulatabad, initiated a rebellion against the Bahmani court. His insurrection is said to have been encouraged by Kondba Deva, a Maratha leader, and drew the support of several nobles from Berar who were related to or aligned with Bahram Khan. The rebellion, however, was short-lived. The Bahmani forces suppressed the uprising, although both Bahram Khan and Kondba Deva reportedly evaded capture and fled westward to Gujarat.

Around this same period, contemporary sources indicate that law and order in Berar had become a serious concern for the Bahmani administration. The region, including present-day Washim, was reportedly affected by rising incidents of highway robbery and banditry, particularly along routes connecting key provincial centres. In response, Sultan Muhammad Shah I is said to have implemented severe punitive measures. Historical chronicles describe mass executions of those accused, with reports that the severed heads of offenders were collected and sent to Daulatabad, the then-capital of the Sultanate. Some sources suggest that as many as 20,000 heads were displayed during the campaign, a figure which reflects the scale and intensity of the effort.

In 1480, during the reign of Muhammad Shah III of the Bahmani Sultanate, the kingdom underwent a major administrative restructuring. The earlier system, which had divided the Deccan into four large territorial divisions known as tarafs, was revised and expanded into eight provinces, aimed at improving governance and revenue collection across the increasingly decentralised state. As part of this reorganisation, the region of Berar, which included present-day Washim district, was divided into two provinces:

- Gawil, to the north, roughly aligning with parts of modern-day Amravati district, and

- Mahur, to the south, named after the historic and religious town of Mahur (or Mahurgad), now in Nanded district.

While surviving records do not clearly define the boundary between Gawil and Mahur, geographic features such as the Balaghat plateau likely influenced the division. It is probable that Washim and Mangrul talukas, situated along the southern edge of the plateau, fell under the Mahur province, while the northern parts of Washim district were included in Gawil. This administrative restructuring likely marked a significant change in the governance of the region and influenced its historical and cultural development.

Mughal Administration and Regional Reorganisation

A major political shift in the Deccan occurred in 1595, when the Mughal Empire formally incorporated Berar into its administrative system. This development followed the appointment of Prince Murad, the fourth son of Emperor Akbar, as the governor of the Deccan. Murad assumed control over Berar, and under his leadership, the region was absorbed into the expanding Mughal Empire.

By 1596, Prince Murad had relocated the provincial capital from Ellichpur (present-day Achalpur, in Amravati district) to Balapur (now in Akola district), transforming it into a key military and administrative centre. This change in headquarters likely had significant implications for neighbouring areas, including Washim, which lay nearby geographically and within the same revenue jurisdiction. The Mughal presence in Washim itself is noted in historical records, including the Ain-i-Akbari, compiled by Abul Fazl in 1596–97. At that time, much of what is now Washim district was included in the Narnala Sarkar (a sarkar being a Mughal term for a revenue and administrative district and within Narnala Sarkar, various parganas (smaller revenue units) are listed) and is believed to have hosted a Mughal garrison.

Territorial boundaries in the Deccan were fluid, and over time, portions of the old Narnala Sarkar came to be divided among modern-day Akola, Buldhana, and Washim districts. The inclusion of Washim in the Mughal revenue system placed it under the regular assessment of land revenue and administrative oversight, linking it more directly to the fiscal structure of the empire.

The Development of Shahpur in Buldhana

In 1597, Prince Murad also oversaw the founding of Shahpur, a planned settlement situated near Balapur. While the town now lies within Buldhana district, its establishment was part of a broader phase of regional consolidation by the Mughals in Berar. The town is believed to have been laid out near the Mun River, with further construction attributed to Mirza Azam Shah, son of Emperor Aurangzeb, who added a palace complex known as Shahpur Fort or Shahpur Palace.

Given Washim’s geographic proximity to Shahpur, Balapur, and Akola (three significant Mughal centres), it is likely that imperial infrastructure and policy had spillover effects on the district. These may have included improvements in trade routes, security arrangements, and the development of supporting settlements.

In the later Mughal period (late 17th to early 18th century), the area of Akola, including parts of Washim, was granted as a jagir (a land assignment) to Asad Khan, who was then the Wazir (Prime Minister) of the Mughal Empire. As part of his administration, Asadgarh Fort was constructed in Akola, and his presence in the region suggests the continued strategic importance of the broader Berar area under Mughal control.

Although Washim is not mentioned specifically in records of Asad Khan's activities, its proximity to Akola and shared governance structure within Berar implies that the district experienced the ripple effects of Mughal investment in the area—especially in security, taxation, and road infrastructure.

Marathas

In the mid-18th century, control over the region passed from the Mughals to the Marathas following the capture of Narnala Fort (now in Akola district). This shift had broader consequences for neighbouring areas, including Washim, which became part of the growing Maratha influence in Berar. Under the Bhosale rulers of Nagpur, a new framework of governance and revenue arrangements was introduced, which likely reshaped the district’s political and economic landscape.

Washim’s Role as a Military Encampment and the Treaty of Kanakpur

In the late 1760s, growing tensions between Peshwa Madhavrao I, the head of the Maratha confederacy based in Pune, and Janoji Bhosale, the Maratha ruler of Nagpur, led to a military confrontation. The disagreement arose from disputes over revenue rights, territorial claims, and political alignment within the Maratha fold. The Bhosales of Nagpur were nominally subordinate to the Peshwa but had grown increasingly autonomous, leading to strained relations.

In 1768–69, the Peshwa launched a military campaign to assert control over the eastern territories. His forces advanced from Aurangabad (now Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar) through a mountain pass in Washim district, using the area as a key transit point. Historical records suggest the army encamped in Washim during this movement. It was here that Madhavrao and Janoji Bhosale met to negotiate peace, marking Washim as the setting for a significant political dialogue.

These discussions led to the signing of the Treaty of Kanakpur, which helped de-escalate hostilities.One article in the treaty, as noted in the Akola district Gazetteer (1977), refers directly to Washim’s economic contribution to the region. It was agreed that the Bhosales would annually send cloth manufactured in Washim and Balapur worth ₹5,000 to the Peshwa. This clause, in many ways, underscores the economic value of Washim’s textile industry during this period.

Balaji Mandir

The religious and architectural landscape of Washim was also shaped during this period. A landmark construction from the late 18th century is the Shri Balaji Mandir, completed in 1779, under the patronage of Bhavani Kaloo, who served as Diwan (chief administrative officer) to the Bhosale rulers of Nagpur.

During his tenure, Kaloo was tasked with a revenue collection expedition to Bengal, a mission that had previously met with little success under others. Before undertaking the journey, Kaloo is believed to have visited a sacred site in Vatsagulma (the ancient name of Washim), where he offered prayers to Sri Vishnu-Balaji. There, he is said to have made a sankalp (vow) that should his mission succeed, he would construct a grand Mandir in honour of Balaji.

With the blessings of Balaji, Kaloo completed the task and returned successfully. On receiving permission from the Bhosales, he began the construction of the Mandir. The work took twelve years, during which Kaloo also served as Subhedar at Karanja (in present-day Thane district). The structure that stands today is a testament to his devotion and administrative capacity.

The Mandir is set within a large paved quadrangle, with a verandah used during special occasions for Bhandaras (community feasts). According to local traditions, several ancient murtis, including those of Sri Vishnu, Ganapati, Parvati, Brahma, and Mahadev, had been hidden underground during earlier periods of turmoil, possibly during the reign of Aurangzeb, and were later rediscovered and installed during Kaloo’s project. A nearby talav, known as Dev Talav, was also excavated under his patronage to serve the religious and ritual needs of the Mandir.

Bhavani Kaloo lived from 1718 to 1808, and his contributions to the religious life of Washim are still remembered today. The Balaji Mandir remains under the care of his descendants, now in their seventh generation, led by Shri Dynanshwara (Deelip Dadasaheb) Narayanrao Kaloo, who serves as the current head of the trust.

Washim’s Agricultural Wealth and Revenue Significance

By the mid-18th century, Washim had become an important centre of agricultural production, particularly known for its cotton cultivation. The area's rich black soil and stable climate supported high-yield farming, which in turn sustained local industries such as weaving and cloth production. This agricultural base helped position Washim as a key node in regional trade circuits. The reference to Washim in the Kanakpur treaty (mentioned above) , specifically its obligation to supply cloth annually, illustrates how agricultural output fed directly into Maratha-era economic arrangements. Together, these factors contributed to Washim’s growing importance as both a revenue-generating district and a supplier within the larger Maratha administrative and trade system.

In addition to its prominence in agriculture, Washim is also believed to have housed a mint during the Maratha period, suggesting its relevance in monetary and commercial activities.. According to the Akola district Gazetteer (1909), the district’s revenue demand during this period stood at approximately ₹24 lakhs, placing it among the most valuable administrative units under the Nagpur Bhosale regime.

Battle of Adgaon (1803) and Its Aftermath

In 1803, during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, the region around Washim again entered a period of upheaval. A major confrontation occurred at the Battle of Adgaon (also known as Argaum), near Sirsoli, just south of present-day Akola. The combined forces of Raghoji II Bhosale and Daulat Rao Scindia confronted the British army under Major-General Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington).

Although Maratha artillery inflicted significant damage at the outset, the British ultimately regrouped and secured a decisive victory. The battle, while not fought directly in Washim, had a destabilizing impact on the region. With troop movements, supply disruptions, and political uncertainty, local economies and village life were most likely severely affected. The defeat, also in many ways, marked a turning point, leading to the gradual erosion of Maratha power in the region.

Pindari Raids and Disruption (1809)

In the years following the war, Washim was among the towns in Berar targeted by Pindari raids—sporadic looting expeditions carried out by loosely organised warrior bands. In 1809, one such raid resulted in Washim being looted, along with other settlements in the region. These incursions added to the instability and economic distress that marked the closing years of Maratha dominance in Berar.

Colonial Period

Washim’s Brief Tenure as a District

In the second half of the 19th century, under British colonial administration, the region of Berar was subject to a series of territorial reorganizations. Within this broader process, a lesser-known development was the brief period during which Washim functioned as an independent district.

The first major reorganization in the region occurred in 1857, when the British divided Berar into two districts: East Berar, with Amravati as its headquarters, and West Berar, administered from Akola. This division set the foundation for later administrative changes.

In 1864, the creation of Buldhana district further altered the regional structure. Four years later, in 1868, Washim was officially designated as a district. It comprised areas from western Berar, including portions of the now-defunct Achalpur and Mehkar districts.

This configuration, however, was short-lived. Subsequent administrative adjustments led to the merger of Washim and Mangrulpir tehsils into Akola district, effectively dissolving Washim’s status as an independent district. These changes reflected a broader pattern of reorganization within British India, where district boundaries were periodically revised in response to administrative, logistical, and economic factors.

In 1903, a formal agreement between the British Government and the Nizam of Hyderabad resulted in the transfer of Berar to British control. This change brought Berar, including Washim, under the jurisdiction of the Central Provinces.

The final major administrative change in this period took place in 1905, when the remaining territory of Washim district was distributed between Akola and Yavatmal districts. Washim would not regain district status until the post-independence reconfiguration of administrative boundaries in Maharashtra.

Severe Drought in 1916 and Raghoji Bhagat

In 1916, a severe drought affected parts of central India, including the Washim region. Raghoji Bhagat, also known as Raghoji Mahar, appears in local accounts as one of the main figures remembered from this time. He was a resident of Tornala, a village located about 16 km from Washim city.

According to oral narratives, Raghoji used his personal grain reserves to provide food during the famine. It is said that his stores were sufficient to feed people across the district for an entire year. This act of large-scale support earned him the local title Varhad’s Kuber, a reference to the deity associated with wealth.

A popular story links the beginning of his economic rise to the discovery of a pot of gold, which he is said to have used to start a business venture. His enterprise grew quickly, and he began working as a moneylender. Over time, he became known as a Sahukar—a term for a wealthy financier. His economic success and visible lifestyle stood out, especially because he belonged to the Mahar community, which at the time occupied a marginalized position in the social structure.

He is remembered for his philanthropic contributions as well, including donations to educational institutions and hostels such as the Sant Chokamela Hostel in Risod and the Kholeshwar Hostel in Akola. It is also believed that he also supported Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in his early initiatives.

Raghoji’s samadhi remains within the village boundaries of Tornala and continues to serve as a site of local remembrance. His life and legacy are also chronicled in the Marathi book Raghnak, which is authored by Shekar Korde.

Post-Independence

After India gained independence in 1947, the region of Berar, including Washim, continued to be administered as part of the Central Provinces and Berar. In 1950, this territory was reorganized into the state of Madhya Pradesh, placing Washim—then a part of Akola district—under its jurisdiction.

A major change followed in 1956 with the States Reorganisation Act, which redrew state boundaries based on language. As a result, Berar was transferred from Madhya Pradesh to Bombay State, aligning the region with its majority Marathi-speaking population.

In 1960, Bombay State was divided to create the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. Washim became part of Maharashtra, where it remained a taluka within Akola district for the next several decades.

In 1998, Washim was established as a separate district. The move was part of a wider administrative reorganization in Maharashtra, aimed at decentralizing governance and improving access to public services in growing regions.

Washim today functions as one of the districts in the Vidarbha region, with its own administrative offices and jurisdiction over several talukas.

Sources

C. Brown. A.E. Nelson ed. 1910.Central provinces and Berar District Gazetteers Akola District. Vol. A - Descriptive, p. 20. Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta.

Census of India. 2001. “District Census Handbook, Washim District.” Series 28, Part A & B. Directorate of Census Operations, Maharashtra, India.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

Kishori Saran Lal. 1950. History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). pp 51-3. The Indian Press, Allahabad, India.

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1977. Akola District. Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra, Bombay.

Meadows Taylor. 1863. “Sketch of the Topography of East and West Berar, in Reference to the Production of Cotton.” Vol. 20, pp. 1-21. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

RJ Dipak Wankhede. 2021. दुष्काळात वाशिम जिल्हा पोसणारे | विदर्भरत्न राघोजी महार | Tornala | Washim | RJ Dipak. Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3KPXqe35xxg

RJ Dipak Wankhede. 2022. Shri Madhyameshwar Sansthan | Washim | श्री मध्यमेश्वर मंदिर | वाशिम | Vidarbha Tourism | RJ Dipak. Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VfLDz3QFS4c

Sachin Dixit. 2018. “Madhyarekha and Madhyameshwar of Washim”. Paper presented at Conference organized by CHAEN and Sathaye College, Mumbai.Academia.edu.https://www.academia.edu/44274664/Madhyarekh…

Sachin Jadhav. 2018. “Madhyarekha: The Ancient Indian Astronomical Median Line That Was Centuries Ahead of Its Time.”Medium.https://medium.com/@sac.jadhav93/madhyarekha…

The News Dirt. 2025. Hisse-Borala Inscription: Vakataka Dynasty’s Ancient Record in Washim. The News Dirt.https://www.thenewsdirt.com/post/hisse-boral…

V.D. Mahajan. 2019. Ancient India. Ed. 14. Chand And Company Limited, New Delhi.

Last updated on 28 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.