Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Iron Age Settlement at Pachkhed

- The Kingdom of Vidarbha and Early Political Developments

- Medieval Period

- Bahmani Sultanate

- Yavatmal under Gond Rule

- Famines

- Administrative Reform Under Mahmud Gawan

- Berar Sultanate and Regional Autonomy

- Ahmadnagar Sultanate and the Annexation of Berar

- Mughal Administration

- Administrative Changes in Berar During Shah Jahan’s Reign

- Dual Power and Early Maratha Influence

- Kanhoji Bhosale and his Maratha Base in Yavatmal

- Raghuji Bhosale and the Consolidation of Maratha Control over Berar

- Unrest and Political Spillovers

- Third Anglo-Maratha War

- Appa Saheb’s Uprising and the Confrontation at Kalamb (1848–49)

- Colonial Period

- Administrative Reorganization in the 19th Century

- Struggle for Independence

- Hari Kishor Newspaper and Colonial Repression

- Loknayak Bapuji Aney and the Jungle Satyagraha

- Jawaharlal Darda and Local Nationalist Networks in Yavatmal

- Post-Independence

- Sources

YAVATMAL

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Yavatmal district has a long history that dates back to ancient times. It is believed to have been part of the kingdom of Vidarbha, mentioned in the epic Mahabharat. In later centuries, it became part of Berar, a historic region in central India that later came under British rule. After independence, Yavatmal became part of Maharashtra and was placed under the Amravati Division. While it shares much of its past with the larger Vidarbha and Berar regions, local events have helped shape its own identity.

Etymology

The origin of the name Yavatmal has been the subject of several interpretations, most of which are grounded in the geographical features of the region. According to one widely held view, the name is derived from the words Yot, signifying “proximate land,” and Maad, meaning “tall trees.” These terms, when taken together as Yotmaad, are understood to denote “land of tall trees,” a description consistent with the natural vegetation that once covered much of the area.

Another interpretation suggests that the name is derived from the Marathi words Yavat, meaning “mountain” and Mal, meaning “row” or “range.” This derivation has been taken to reflect the district’s undulating terrain, particularly the low-lying hills associated with the Ajanta ranges.

A third explanation connects the name to Yevata, an earlier term meaning “mountain,” and Lohara, a nearby village. In this version, mal is considered a variation of mahal, a historical designation used for an administrative town, suggesting that the area may have held administrative importance in an earlier period.

Ancient Period

The territory that now forms Yavatmal district has, at various times, fallen under the authority of different kingdoms. Its early history is difficult to reconstruct in full due to the scarcity of information. However, available archaeological findings and a few literary references allow for a general outline, particularly when considered in relation to the broader histories of Vidarbha and Berar (the cultural and political spheres to which Yavatmal has historically belonged).

Iron Age Settlement at Pachkhed

One of the earliest glimpses into Yavatmal’s ancient past comes from Pachkhed, a village in Babhulgaon taluka of the district, where excavations have revealed traces of an Iron Age settlement dating to around 1500 BCE. Excavations carried out by the Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology at Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University brought to light material remains pointing to continuous occupation across different periods. Of these, two are dated to the ancient period.

The first phase, dated to around 1500 BCE, belongs to the Iron Age. Artefacts recovered from this layer include iron and copper furnaces, pottery bearing early Brahmi inscriptions, terracotta figurines, decorated ceramics, and beads made of semi-precious stones. These findings suggest the presence of a settled community engaged in metalworking and craft production.

A second phase, dated to the Satavahana period (1st century BCE to 3rd century CE), includes remains linked to lime use. Lime, typically produced by heating limestone or shells, was used in building materials such as plaster and mortar. Its presence at the site points to activity associated with construction or structural work during this time.

Notably, based on material recovered at the site, some scholars have suggested that Pachkhed may have been connected to regional trade routes. The village lies roughly between Bhokardan (in present-day Jalna district) and Pauni (in Bhandara district), both of which were active centres in early historic Maharashtra. This position has led to the view that Pachkhed may once have formed part of a route linking these sites.

The Kingdom of Vidarbha and Early Political Developments

The Yavatmal district is widely believed to have once been part of the ancient Vidarbha Kingdom. Some accounts identify the present-day village of Kelapur (Yavatmal district) with Kuntalapur which is a city associated with this kingdom. While this link remains unconfirmed and contested, it points to the possibility that parts of the district were once included within the territory of this kingdom.

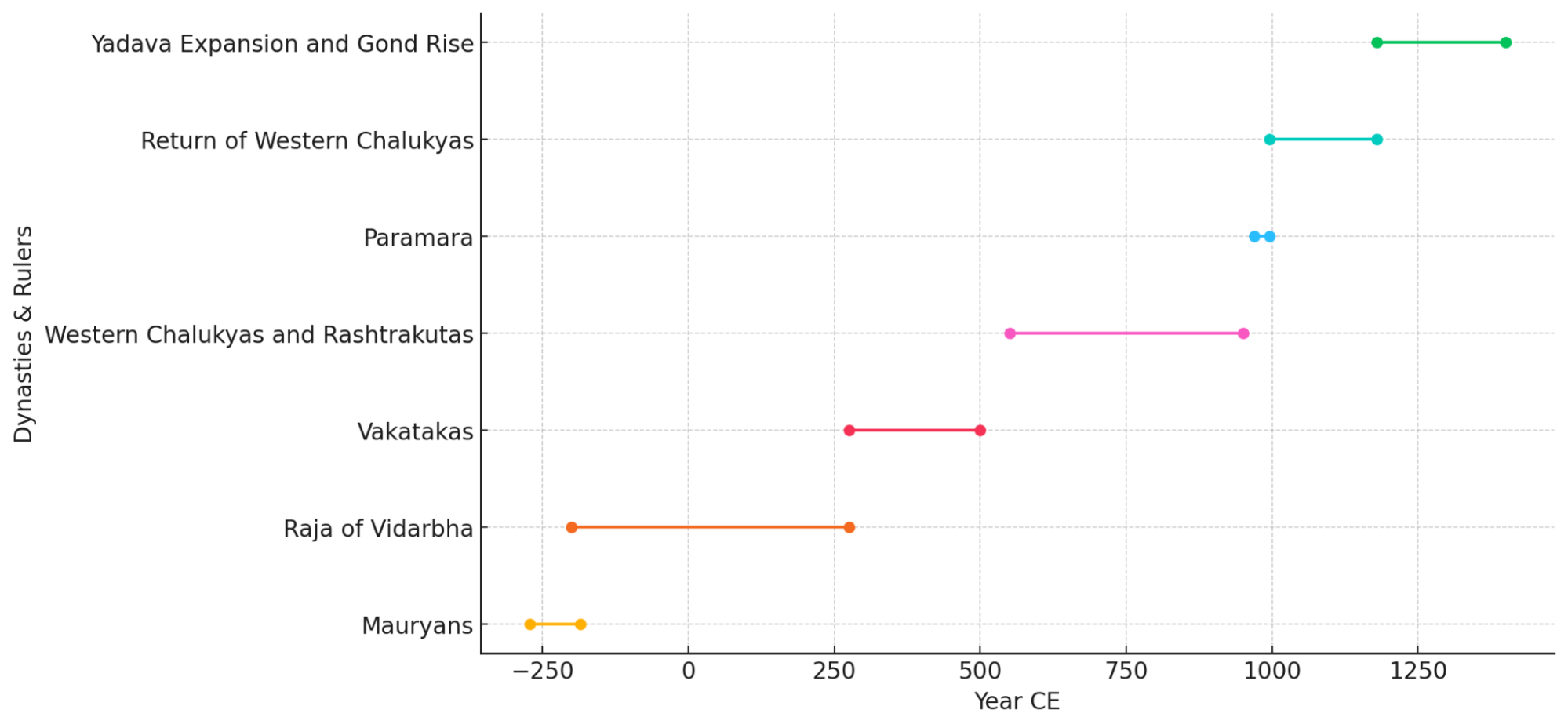

By the 3rd century BCE, according to historical records, the wider Berar region, within which Yavatmal is situated, had come under the control of the Maurya Empire. While there are no specific references to Yavatmal known yet from surviving records from this period, its inclusion in Berar implies that it was likely incorporated into the administrative system established by the Mauryas.

Following the decline of Mauryan authority toward the end of the 2nd century BCE, centralised control weakened across much of the subcontinent. In this context, local rulers began to assert greater autonomy. The district Gazetteer (1908) notes that the Raja of Vidarbha had begun to exercise a degree of independence even before the formal collapse of Mauryan rule. This period saw the emergence of new powers, among them the Sungas, who succeeded the Mauryas in northern India and gradually extended their influence into the Deccan through a series of military campaigns.

A tale reflecting the tensions of this period is found in Malavikagnimitram, a Sanskrit play by the poet Kalidas, composed several centuries after the events it portrays. Though primarily a courtly drama, the play includes a subplot involving a military conflict between the Sunga Empire and the kingdom of Vidarbha. In the story, Agnimitra, the son of the Sunga ruler Pushyamitra, is drawn into a dispute with the Raja of Vidarbha. The war ends with the kingdom of Vidarbha divided between two brothers, one remaining as ruler, and the other supported by the Sungas.

Interestingly, the conflict is also mentioned in the district Gazetteer (1908), which records that Agnimitra “found it necessary to make war on his neighbour, the Raja of Vidarbha. The latter was defeated, and the river Wardha was made the boundary between the two kingdoms.” The Wardha River is described as the boundary between the two territories. Since Yavatmal lies close to the river, it may have formed part of this divided zone.

Between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE, the Yavatmal region likely fell within the sphere of influence of the Vakataka dynasty, which held sway over much of central India during this period. Their presence in the Deccan region is reflected in the Ajanta Caves, where several inscriptions attest to the patronage of Vakataka rulers. It is worth noting that Washim, a town not far from Yavatmal, is recorded as having served as the seat of a Vakataka branch; this administrative presence in close proximity, in many ways, places Yavatmal firmly within the bounds of their political and cultural reach. Although the Vakatakas had multiple capitals over time, some historians believe that one of their important centres was at Bhandak (near present-day Chandrapur). If this holds true then, it would place Yavatmal close to a major political and administrative hub during this period.

Following the decline of the Vakatakas, powerful dynasties like the Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas rose to prominence in the Deccan. However, little is known about the impact they left on Yavatmal. In the latter half of the 10th century, the region came under the expanding influence of Vakpati II Munja, a Paramara king from Malwa. His kingdom stretched as far south as the Godavari River, encompassing much of Berar and possibly parts of Yavatmal. However, around 995 CE, he was defeated and captured by Taila II, a Chalukya ruler, bringing Berar once again under Chalukya control.

By the end of the 12th century, the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri (modern Daulatabad) had begun to rise, taking over many northern territories from the declining Chalukyas. While it is not known whether the Yadavas directly governed Yavatmal district, their cultural influence is visible in surviving structures such as the Kamaleshwar Mahadev Mandir at Lohara and the Kedareshwar Mandir at Pangari.

It is more likely that the eastern parts of the region, particularly areas closer to present-day Chandrapur, gradually came under the influence of Gond rulers.

Medieval Period

During the medieval period, Yavatmal district was influenced by shifting regional powers and fluctuating administrative arrangements, shaped by the broader political developments in the Deccan. While it was not a consistent seat of centralized authority, the district remained deeply connected to the contest for control among emerging kingdoms and local forces in the Berar and Vidarbha regions.

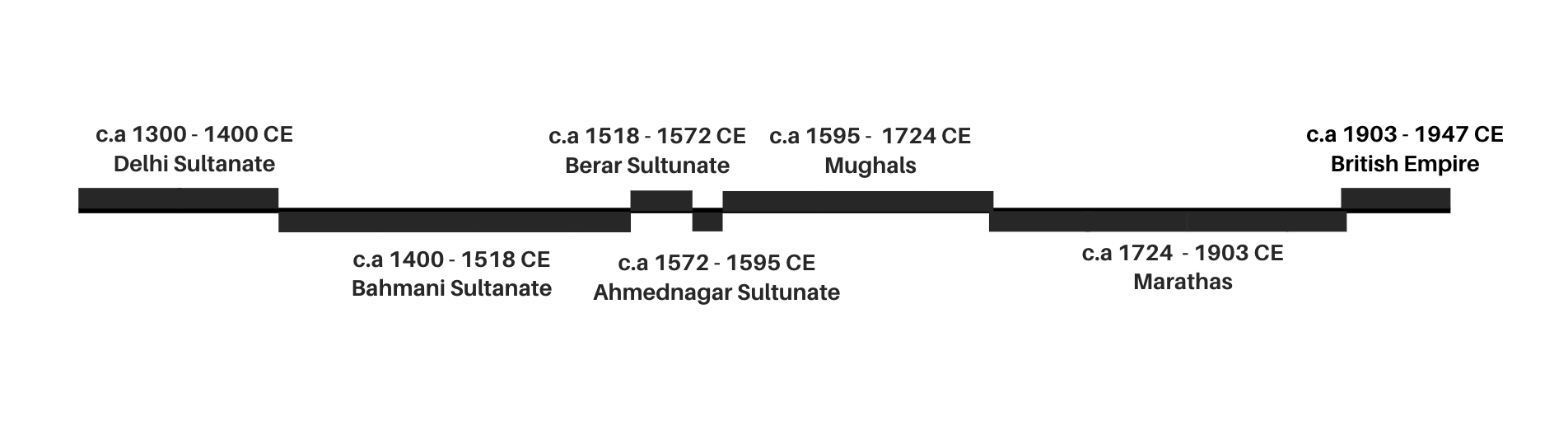

In 1294, Alauddin Khilji launched a raid into the Deccan, marking the Delhi Sultanate’s first military activity in the region. However, according to the district Gazetteer (1908), the district lay outside the core zones of these incursions. It is unlikely that the Delhi Sultanate ever exerted direct administrative control over Yavatmal. The region likely remained under indigenous powers such as the Gonds or remnants of the Yadava dynasty during this time.

Bahmani Sultanate

In 1347, Alauddin Bahman Shah established the Bahmani Sultanate in the Deccan. By 1374, Berar became one of its four main provinces. Yavatmal, as part of northern Berar, was incorporated into this territory, though it was distant from the Sultanate’s central hubs.

In the 1390s, internal conflicts between the Bahmanis and the Vijayanagar Empire weakened the Bahmani hold on the region. In this period, it has been noted that Hoshang Shah of Malwa attempted to advance into Berar. His forces were repelled by Ahmad Shah Bahmani, who is recorded to have moved through the Yavatmal region as part of this campaign. These movements suggest that the district functioned as a strategic corridor, even if it was not a centre of direct conflict.

Yavatmal under Gond Rule

During the same period of instability, Narsingh Deo, a Gond ruler based in Chanda (present-day Chandrapur), extended his authority over parts of Berar. Around 1398–99, taking advantage of weakened Bahmani control, he occupied the Yavatmal district. Bahmani forces, led by Firoz Shah, later reasserted control.

Despite the loss of territorial control, Narsingh Deo remained an active political figure in the region. The District Gazetteer (1908) notes his involvement in a later conflict, when Hoshang Shah of Malwa attempted to invade Berar. Ahmad Shah Bahmani repelled the advance, reportedly with support from Gond forces. After the campaign, it has been noted that Narsingh Deo travelled with Ahmad Shah through Yavatmal and was presented with gifts at Mahur; which is, in many ways, a gesture marking coordination between the two sides during a period of contested control.

Famines

In 1473 and 1474, during the reign of Muhammad III, the 13th king of the Bahmani dynasty, the region faced severe droughts which led to a catastrophic famine. The district Gazetteer (1908) records that “the district suffered equally with the rest of Berar”. It further notes that much of the population either succumbed to starvation or fled to nearby regions like Malwa for sustenance.

In 1630, another severe famine struck the region of Berar, including Yavatmal. While historical data from this period is limited, the famine likely had significant and widespread impacts on the district’s population and social conditions.

Administrative Reform Under Mahmud Gawan

During the governance of the Bahmani Kingdom in the late 15th century, significant administrative changes reshaped the region, particularly in South-Eastern Berar, which included the Yavatmal District.

Under the guidance of Mahmud Gawan, a prominent advisor and a minister in the court of Muhammad III, the King began restructuring the kingdom’s administrative divisions in 1480. The initial four provinces were subdivided into eight, marking a critical shift in governance.

Specifically, the region of Berar was divided into Gawil (now in Amravati district) and Mahur (now in Nanded district) provinces. Yavatmal district became part of the Mahur province. Khudawand Khan was appointed governor of South-Eastern Berar, with Mahur as his base. It is mentioned in historical accounts that the Bembla River, which flows through Yavatmal was likely used to define the province’s boundary, emphasizing Yavatmal’s geographic and strategic position in South-Eastern Berar.

Berar Sultanate and Regional Autonomy

Following the weakening of central authority of the Bahmani Sultanate, regional governors declared independence. In 1490, Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk declared Berar an independent kingdom, becoming its first sultan. Although Yavatmal lay within the Mahur province, its local governor Khudawand Khan continued to rule semi-autonomously and did not declare independence.

After Fathullah’s death in 1504, Berar was reunified under Alauddin Imad Shah, followed by his son Darya Imad Shah around 1529. However not much is known about how Yavatmal was affected by this change.

Ahmadnagar Sultanate and the Annexation of Berar

During the mid-16th century, the Imad Shahi dynasty in Berar began to lose political strength due to internal instability and shifting alliances in the Deccan. As neighboring sultanates grew more assertive, particularly Ahmadnagar under the Nizam Shahis, Berar found itself increasingly drawn into regional power struggles.

Tensions between Berar and Ahmadnagar Sultanates escalated into a long and intense conflict by the 1570s. In 1572, during the reign of Murtaza Nizam Shah I, Ahmadnagar launched a sustained military campaign to annex Berar. After a series of battles and sieges, particularly the capture of strongholds like Narnala (which lies in Akola district) and Gavilgad (which lies in Amravati district) the Ahmadnagar Sultanate succeeded in deposing the last Imad Shahi ruler.

By the mid-1570s, Yavatmal and the surrounding region were formally annexed into the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. However, control over the area remained unstable due to ongoing resistance, local unrest, and interference from other Deccan powers such as Khandesh and Bijapur. This period of contested rule continued until 1596, when Berar, including Yavatmal, was ceded to the Mughal Empire by Chand Bibi, then regent of Ahmadnagar, following sustained Mughal military pressure.

Mughal Administration

In 1596, after Berar was ceded to the Mughals by the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, a detailed account of the province was added to the Ain-i-Akbari. It is noted in the district Gazetteer (1974) that this account was compiled “immediately after the treaty of Ahmadnagar,” before Mughal officers had time to “settle the province and readjust boundaries.” It thus reflects the continuance of the administrative setup of the Nizam Shahi, Imad Shahi, and possibly Bahmani period during the initial years of Mughal rule.

Back then, Berar was divided into thirteen sarkars (a term used to describe something akin to district-level units). The present-day Yavatmal district comprised most of Kalam and Mahur, although “some few mahals of these sarkars lay beyond the present limits of the district.” Yavatmal appears in the record as a pargana headquarters under the name Yot-Lohara, which combines the words “Yot” (a corruption of Yevata) and Lohara, a village nearby. The estimated land revenue demand for what is now Yavatmal was “rather more than ten lakhs of rupees” and it had a relatively flourishing agricultural economy.

In the early 1600s, Mughal authority in Berar was actively contested by the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, under the leadership of Malik Ambar, a powerful regent and military commander. Around 1610, he recaptured Ahmadnagar and gained control over much of Berar, including areas like Yavatmal. Over the next several years, control shifted back and forth between the Mughals and Ahmadnagar forces. Around 1613, he introduced a new revenue settlement in Berar, aimed at improving efficiency. This rehaul, possibly, reached to and affected Yavatmal.

In 1626, a Mughal official named Khan Jahan Lodi handed over parts of Berar, including Yavatmal, to the Ahmadnagar Sultanate in return for a large payment. According to the Gazetteer, “the commanders of military posts in the Balaghat... surrendered them to the Deccani officers and retired to Payanghat.” Locations such as Kalam and Mahur were likely among the posts affected by the administrative uncertainty during the period.

Administrative Changes in Berar During Shah Jahan’s Reign

When Shah Jahan became emperor in 1628, he introduced a major administrative reorganization across the Deccan. Until then, Berar, Khandesh, and parts of the former Ahmadnagar territories were managed together under one provincial governor, usually based in Burhanpur.

In 1634, this arrangement was restructured. The region was divided into two broad zones based on geography with Balaghat, referring to the upland plateau areas, and Payanghat, referring to the lower river plains.

As part of this change, Yavatmal was placed in the Balaghat division, along with other upland parts of Berar. This change in territorial affiliation likely had significant implications for the governance and administrative dynamics of the district during this period.

Dual Power and Early Maratha Influence

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Yavatmal, like much of the Deccan, came under the influence of a weakening Mughal administration and the rising Maratha power. This led to a system of dual governance, where both Mughal or Nizam and Maratha authorities exerted control over the region, often simultaneously.

In 1719, Emperor Farrukhsiyar, the tenth Mughal Emperor, formally recognized the Maratha right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi across the six Deccan provinces, including Berar. According to the district Gazetteer, this sanad "legalised their right of doing so," marking a shift in authority, but not without resistance. However, this was contested. Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I, recently appointed viceroy of the Deccan and founder of the Hyderabad state, refused to accept Maratha rights in Berar, leading to conflicts over revenue and territorial control would continue for decades.

Kanhoji Bhosale and his Maratha Base in Yavatmal

One of the earliest prominent Maratha leaders in Berar was Kanhoji Bhosale, son of Parasoji Bhosale and cousin of Raghuji Bhosale. According to the district Gazetteer (1974), his headquarters were located at Bham, a fortified site in what is now Yavatmal district (It is important to note that the colonial district Gazetteer (1907) does not make any mention of Kanhoji's presence at Bham. Instead, it specifically mentions that his nephew, Rughuji (mentioned below), “before his appointment as Sena Sahib Subah in 1734, had established himself at Bham.”)

Under Kanhoji’s leadership, it is said that the Bhosales consolidated their position in Berar and Gondwana and extended their influence eastward toward Orissa. Interestingly, it is noted in the district Gazetteer (1974) that “the Bhosales are referred to even up to the treaty of 1803 with the English, as the Rajas of Berar,” reflecting the sway they held over the region.

However, Kanhoji’s growing autonomy and increasing distance from the Maratha court led to political friction. Chhatrapati Shahu I, the Maratha king, began to view Kanhoji with suspicion, particularly for failing to send revenue accounts from his jagir and for not fully aligning with the court at Satara. These tensions deepened when Kanhoji began aligning with Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I. According to the Gazetteer, this inevitably, contributed to the “strained relations between the Marathas and the Nizam,” especially due to the Nizam’s efforts “to seduce Sahu’s Sena Saheb Subha, Kanhoji Bhosale and his Sar Lashkar [major general], Sultanji Nimbalkar.”

In response, Shahu dispatched forces to detain him. Raghuji Bhosale was tasked with confronting his cousin. With support from other Maratha commanders, Raghuji laid siege to Bham Fort. After the death of Kanhoji’s commander Tukoji Gujar and a series of military losses, Kanhoji retreated to Mahur (Nanded district) and was eventually captured. He was taken to Satara, where he died in captivity.

Raghuji Bhosale and the Consolidation of Maratha Control over Berar

Perhaps during the campaign against Kanhoji, Raghuji Bhosale’s hold over Yavatmal began to strengthen. It is noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1907) that his base was located at Bham (Yavatmal district), “where the ruins of his palace [Rajwada] are still to be seen.” This early foothold suggests that Yavatmal played a key role in Raghuji’s rise and in the shaping of Maratha administration in Berar. Notably, it predates his formal appointment as Sena Saheb Subha in 1734, underscoring the strategic significance of the district during his early years of influence.

Following his appointment, Raghuji expanded his administrative reach further, with Nagpur emerging as his central seat of power. His authority was later reinforced when the Nizam of Hyderabad formally recognised him as mokasadar (revenue assignee) of Berar, granting him the right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi through his own officers. However, this arrangement did not displace the Nizam’s own tax officials, resulting in overlapping demands on the same population.

The consequences of this dual administration were severe. As the district Gazetteer (1974) notes, “Military foragers from both sides ravaged the countryside, and many peasants, driven to despair, gave up cultivation and turned to plunder themselves,” contributing to widespread instability and hardship across the region.

Unrest and Political Spillovers

In 1770, a rebellion against the Nizam of Hyderabad broke out in southern Berar, led by the zamindar of Nirmal (in present-day Telangana). Defeated by the Nizam’s general, Zafar-ud-Daulah, the zamindar and his followers fled across the Penganga River into Yavatmal, drawing the region into the fallout. This episode highlights the district's role as a buffer and refuge in times of regional unrest.

Third Anglo-Maratha War

During the final years of Maratha power, Yavatmal again became a zone of military activity. In 1818, during the Third Anglo-Maratha War, Peshwa Baji Rao II used the district as a corridor while moving to support Appa Sahib Bhosale of Nagpur, who was resisting British intervention.

According to British accounts, towns in Yavatmal like Wani, and Pandharkawada became transit points for both Maratha forces and British detachments. Ganpat Rao, a Maratha commander, attempted to cross the Wardha River within Yavatmal but was intercepted and defeated by Lt. Col. Adams, effectively halting the Peshwa’s eastern campaign. Though no major battle is known to have occurred in the district, Yavatmal’s roads and river crossings played a strategic role in this battle.

Appa Saheb’s Uprising and the Confrontation at Kalamb (1848–49)

A decade later, Yavatmal once again became the site of a brief but violent uprising. In 1848, a man claiming to be Appa Saheb, the former Raja of Nagpur, led a rebellion in Berar and drew considerable support from Yavatmal. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1907), the region, then part of Berar under the nominal authority of the Nizam of Hyderabad, saw growing unrest as the claimant gathered support from discontent local officials and enlisted Rohilla mercenaries (Afghan-origin soldiers-for-hire from northern India). Over time, his force is said to have grown to nearly 4,000 men.

By May 1849, his force had established a camp in the hills near Kalamb, which lies in present-day Yavatmal district. A British detachment under Brigadier Onslow was sent to confront them. In the fighting that followed, the rebels were pushed back, but Onslow was killed after a fall from his horse. The rebel leader escaped, retreating with part of his force.

A month later, British troops under Brigadier Hampton caught up with the remaining rebels after several days of pursuit. In the final clash, Hampton was seriously wounded, but the rebel leader was captured and his followers scattered. The revolt was short-lived, but its scale and local support revealed the underlying tensions in the region during the final years of Nizam-era rule.

Colonial Period

In 1833, the Yavatmal region, along with the rest of Berar, was formally assigned to the British East India Company by the Nizam of Hyderabad. Although Berar remained nominally under the Nizam’s dominion, a treaty signed in 1835 transferred its administration to the British. This began a unique arrangement where British officials governed Berar on behalf of the Nizam, with overall supervision resting with the British Resident at Hyderabad. During this time, Berar was reorganized into North and South divisions.

Administrative Reorganization in the 19th Century

Following the Revolt of 1857, further administrative restructuring occurred. Berar was divided into East and West Berar, with Yavatmal falling under East Berar. As part of these changes, the districts of Amravati and Akola were established in 1858. At this time, most of what is now Yavatmal district except the Pusad taluka was incorporated within East Berar, but a distinct Yavatmal district did not yet exist.

That changed in 1864, when the talukas of Yavatmal, Darwha, Kelapur, and Wun were grouped together to form a new district initially called South-East Berar, later renamed Wun District. This administrative setup lasted until 1903, when the Nizam formally leased Berar to the British Government of India, transferring full administrative control. This led to its integration into the Central Provinces, and in 1905, the Pusad taluka was added following the dissolution of Washim district. That same year, the district was renamed from Wun to Yeotmal (Yavatmal), establishing its present administrative identity.

Struggle for Independence

In the early 20th century, Yavatmal district became increasingly involved in India’s national freedom movement, which was gaining momentum across the Central Provinces and Berar. Local leaders and activists began aligning with the broader nationalist cause, particularly in response to Lord Curzon’s decision to partition Bengal in 1905, a move that triggered widespread unrest across the country. By this time, political consciousness in the district had started to grow, with connections emerging between Yavatmal and prominent national leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak.

The momentum built in the years following continued into key phases of the national struggle, including the Non-Cooperation Movement, Civil Disobedience Movement, Salt Satyagraha, and Quit India Movement. Local leaders such as Loknayak Bapuji Aney, P.H. Gosavi, Gopalrao Kothekar, Narayan Balaji Patil, and Jawaharlal Darda were among those who played an active part in mobilizing the district’s participation.

Hari Kishor Newspaper and Colonial Repression

As political activism expanded in Yavatmal in the early 20th century, so too did colonial efforts to suppress dissent. A prominent early example of this was the prosecution of Hari Kishor, a local weekly newspaper published from Yavatmal and edited by Narhar Vithal Bhave. The paper had a circulation of about 750 copies in 1909 and regularly published commentary on nationalist issues.

According to the district Gazetteer (1974), the paper played a notable role in early nationalist mobilization. The editors had invited Bal Gangadhar Tilak to Yavatmal from Amravati, and it was on this occasion that Tilak was publicly addressed for the first time as “Lokmanya,” a title that would come to define his political legacy.

The newspaper came under official scrutiny in 1907 when it published a series of articles protesting the arrest of Lala Lajpat Rai. On this basis, the government initiated prosecution under Section 124-A of the Indian Penal Code (sedition). The Gazetteer (1974) records “The Harikisor had published three articles on the arrest of Lajpatrai and it was on the ground of these articles that the paper was prosecuted.”

As a result, on 12 November 1907, Prithvigir Hargir, the publisher, was sentenced to two years of rigorous imprisonment and fined Rs. 1,000. The editor, Narhar Vithal Bhave, was later sentenced to five years’ rigorous imprisonment, and the printing press was confiscated.

But Hari Kishor’s editorial stance extended beyond national events. It frequently used local incidents to expose the contradictions of colonial rule. One article, which appeared to deepen government hostility toward the paper, reported on a ceremonial event during the Chief Commissioner’s visit to Pusad (which lies in Yavatmal district). The function, held at the Anglo-Vernacular English School, featured flag salutes, hymns, speeches, and the distribution of certificates and sweets, all meant to showcase the supposed benefits of British rule: railways, postal services, and education.

Instead of repeating this praise, Hari Kishor questioned it. The article pointed out how ordinary people had been excluded from the event, and how local elites had supported it mostly to show their loyalty to the British. It also criticised how funds like the Paisa Fund and Mushti Fund, which were meant for public welfare, were being used as a pretense of their benevolence, rather than to truly help the people. Even after the imprisonment of its editor, Hari Kishor continued to voice resistance. Later issues drew attention to Bhave’s deteriorating health in Nagpur Jail, using it to question British claims of justice and humanity.

This combination of nationalist reporting and pointed local criticism made Hari Kishor both influential and threatening in the eyes of the colonial government. As it is noted in the district Gazetteer (1907), its repression was part of a wider effort to control the local press in the years leading up to the Press Act of 1910 with “the Harikisor of Yavatmal, the Hindu Kesari and Desa-sevak” being among the major newspapers who were consistently persecuted by the them.

The repression of Hari Kishor highlights how local platforms in places like Yavatmal became part of the broader national struggle. The newspaper's criticism of colonial officials and local elites challenged the colonial narrative and reflected broader anxieties in the British administration, especially as nationalist ideas began to circulate across the country.

Loknayak Bapuji Aney and the Jungle Satyagraha

By the 1930s, the district became the site of one of the earliest organized civil disobedience campaigns against colonial forest policy. The movement in Yavatmal was led by Bapuji Aney, a prominent lawyer and freedom fighter.

Aney had initially practiced law in the district after earning his degree from Calcutta University in 1907. His early involvement in nationalist journalism, writing for Hari Kishor in 1910, led to punitive action by the colonial government, including the suspension of his legal license for one year. Over the next two decades, he became an increasingly influential figure, aligning closely with Tilak’s brand of assertive nationalism and later emerging as a regional leader within the Indian National Congress. He became associated with the Home Rule League, presided over the Vidarbha Pradesh Congress Committee in 1921, and later founded the Lokmat newspaper in Yavatmal in 1918.

In July 1930, during the Civil Disobedience Movement, Aney led a Jungle Satyagraha in Pusad (Yavatmal district), protesting colonial restrictions on forest use. Along with a group of volunteers, he entered reserved forest land and cut grass as a symbolic act of defiance. He was arrested, charged under Section 379 of the Indian Penal Code (theft), and sentenced to six months of imprisonment.

The movement quickly spread throughout Berar. According to the Digital District Repository website, over 300 individuals were said to have been arrested from Yavatmal district alone. The satyagraha drew broad support, including notable involvement from local indigenous communities.

Aney’s leadership during this period earned him the title “Loknayak” ("People’s Leader") among supporters. The campaign was one of the earliest forest-based satyagrahas in India and highlighted how environmental and economic issues were central to local resistance under colonial rule.

Jawaharlal Darda and Local Nationalist Networks in Yavatmal

Jawaharlal Amolakchand Darda (1923–1997), widely known as Babuji, was a freedom fighter, journalist, and senior political leader. Deeply influenced by Gandhian ideals, he played a key role in shaping early Congress activity in Yavatmal and remained active in state politics until the 1990s.

Born in 1923, Darda joined the Quit India Movement at the age of 19 and was sentenced to a year and nine months in jail. While imprisoned in Jabalpur Jail, he helped organise a Youth Conference on 10 August 1942. In 1944, he established the Azad Hind Sena in Yavatmal to mobilise nationalist youth action.

Following his release, Darda became President of the Yavatmal City Congress (1946–56) and played a key role in consolidating post-independence Congress networks in the Vidarbha region. He later served in the Maharashtra legislature, holding several ministerial portfolios, including industries, energy, and public works.

Beyond politics, he was also the founding editor of Lokmat and chairman of the Lokmat Media Group, which grew into one of Maharashtra’s largest regional media platforms. In 2013, he was posthumously honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the UK House of Commons for his contributions to the freedom movement and to public initiatives in education and healthcare across the state.

Post-Independence

After India gained independence in 1947, the country undertook a major administrative restructuring to align state boundaries with linguistic and cultural identities. Until that point, most provinces were organized based on colonial administrative convenience rather than regional or linguistic considerations.

In 1953, the Government of India established the States Reorganization Commission (SRC) to examine the issue. Based on its recommendations, the States Reorganization Act was passed in 1956, leading to the reconfiguration of state boundaries primarily along linguistic lines.

Yavatmal, which had previously been part of the Central Provinces and Berar, was initially transferred to the bilingual Bombay State. This state included regions where both Marathi and Gujarati were spoken. However, the linguistic composition of Bombay State led to further demands for a clearer division.

On 1 May 1960, Bombay State was reorganized into two separate states: Maharashtra for Marathi-speaking areas and Gujarat for Gujarati-speaking areas. As a predominantly Marathi-speaking district, Yavatmal became part of Maharashtra.

Sources

Atul Bhatia. 2023. Jawaharlal Darda’s biography “Jawahar” launched in Delhi: Know about him. India TV News.https://www.indiatvnews.com/news/india/jawah…

D.D. Sathe et al. 1974. Maharashtra Gazetteers: Yeotmal District. Department of District Gazetteers, Bombay, India.https://archive.org/details/dli.csl.3289/mod…

Digital District Repository Detail. 2025. Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav. Ministry of Culture, Government of India. Yavatmal, Maharashtra.https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/district-reopsi…

History of Yavatmal. n.d. Yavatmal Online.https://www.yavatmalonline.in/city-guide/his…

History369. 2018. Vaakaataka Vakataka kingdom history. Encyclopedia of Indian History.https://history369.blogspot.com/2018/07/vaak…

Jagran Josh. 2013. Freedom fighter Jawaharlal Darda conferred House of Commons award posthumously. Jagran Josh.https://www.jagranjosh.com/current-affairs/f…

Mahur Fort. n.d. Hindu Janajagruti Samiti.https://www.hindujagruti.org/history/39846.h…

Map of Yavatmal District. n.d. यवतमाळ जिल्हा, महाराष्ट्र.https://yavatmal.gov.in/map-of-district/

National Archives of India. 1909. “Prosecution of Hari Kishore newspaper under section 124-A, Indian Penal Code; Decision of the Judicial Commissioner, Central Provinces that Section 517, Criminal Procedure Code, does not provide for the confiscation of the press at which a newspaper which publishes seditious matter is printed.”

National Archives of India. 1909. “Selection from the Native Newspapers Published in the Central Provinces for the Week Ending 31st July 1909.”

Russell R.V. 1908. Gazetteers of the Central Provinces and Berar, Yavatmal Gazetteer. Vol. A. The Gazetteers Department - Yeotmal.

Shirish Borkar. 2024. Iron Age Smelting Site Found in Yavatmal.The Hitavada. https://www.thehitavada.com/Encyc/2024/5/12/…

Sir William Wilson Hunter.Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. 7. Digital South Asia Library.https://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazettee…

W. H. Moreland and A. Yusuf Ali. 1918. Akbar's Land-Revenue System as Described in the "Ain-i-Akbari". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press.https://www.jstor.org/stable/25209343

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.