Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Labor

- Pioneering Women Agriculturalists

- Shailaja Popatlal Navander

- Padma Shri Rahibai Popere

- Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

- Hurda

- Sugarcane Tiger/Wagh

- Types of Farming

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Kandyache Got

- Dahli/Kumri (Kumari) Cultivation

- Use of Technology

- Drip Irrigation and Sprinkler Irrigation

- Droughts in Marathwada: Challenges and Government Initiatives

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth

- Cooperative societies

- Farmers' Producers Organizations (FPOs)

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

AHILYANAGAR

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

The district of Ahilyanagar, located in the Paschim Maharashtra region of the state, is home to a variety of landforms. The district's western part has hill ranges such as Kalsubai, Adula, Baleshwar, and Harishchandragad. The central region consists of a plateau, which includes Parner and Ahilyanagar talukas and parts of Sangamner, Shrigonde, and Karjat talukas. The southern and northern regions have relatively flatter topography. The district is primarily drained by two major rivers, the Godavari and the Bhima, a tributary of the Krishna. Other significant rivers flowing through the district include the Paravara, Mula, Sina, and Dhora.

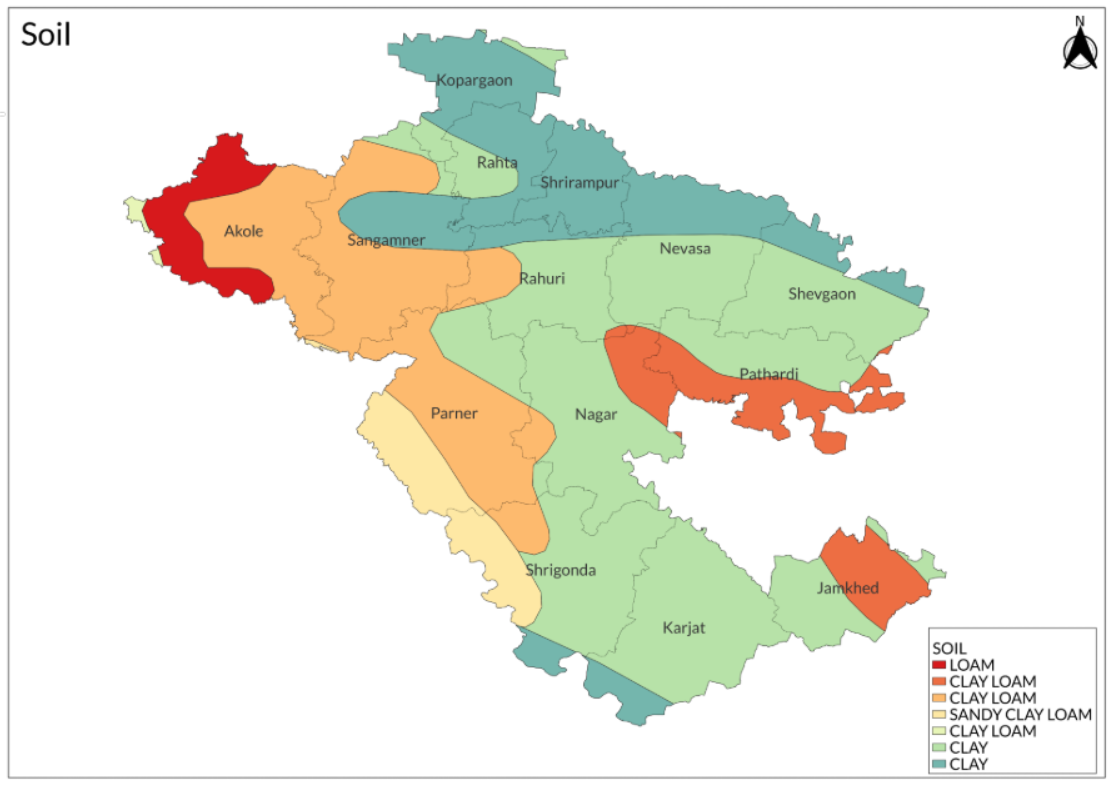

Known for its rich black soil and grey soil, typical of the Deccan Plateau, the district’s economy is primarily agricultural, with Sugarcane, Jowar, and Wheat as the major Rabi crops and Pearl Millet and Soybean as major Kharif crops.

The geographical features of the district make the landscape fertile, and agriculture thrives as a backbone of the region. One of the important aspects of agriculture in the region is that the practice is genderless. Women play an active role in the region, often taking the lead in various farming activities.

Crop Cultivation

Agriculture in the district has roots dating back to the Harappan era, with evidence found at the Daimabad archaeological site in Ahilyanagar. Discovered in 1958, this site, situated on the left bank of the Pravara River, dates back to the late Neolithic age, around 2300 BCE. The inhabitants of ancient Daimabad were believed to be settled agriculturists living in modest mud or thatched huts. Notably, Daimabad is often associated with a ‘Harappan affinity,’ though this connection remains a subject of ongoing scholarly debate.

Modern-day agriculture in the district continues to thrive on the Deccan Plateau’s fertile landscape. According to the ICAR’s (Indian Council of Agriculture Research) agriculture contingency report for the district of Ahilyanagar, the weather in the district is usually hot-semi-arid, and the soil is divided into three major types: Shallow grey soils, Medium deep black soils, and Deep black soils. In addition to this, the district is drained by rivers such as Godavari, Bhima, Mula, Sina, Dhora, and Parvara. The area is conducive for crops such as Sugarcane, Soybean, Cotton, Maize, Jowar, Green gram, Red gram, Black gram, Bajri (Pearl millet), Moong, Wheat, Bengal gram, Nigerseed, Paddy, and Groundnut. Even small amounts of rice are cultivated throughout the district.

Horticulture crops such as Pomegranate, Kagzi Lime, Guava, Mango, Chickoo, Onion, Tomato Pea, Brinjal, Chilli, and flowers such as Sunflower, Marigold, Chrysanthemum, Aster, Tube rose (Nishigandha), and Rose are also cultivated.

Cultivated land is classified into two main categories: jirayat (dry-crop lands) and bagayat (watered lands). Dry-crop lands are further divided into kharif and rabi crops. Kharif crops are sown in June or July and harvested between August and November, while rabi crops are sown in October and November and harvested in February and March. In the western hilly region near Akola (Akole), early crops such as rice and coarser hill grains are of prime importance. During the cold season, crops like wheat, peas, gram, and lentils are grown. In other parts of the subdivision, both early and late harvests are significant, though in certain areas, the late harvest takes precedence.

The primary early crops in the eastern region of the district include bajri (pearl millet) mixed with pulses such as tur and hulga (horse gram). Oilseeds like niger seed, hemp, sesame, Indian millet, cotton, and tobacco are also grown, especially in poor shallow soils near the hills. Hot weather crops, such as mug and udid, are cultivated only in fertile, moisture-retaining land and are harvested in late August, after which the land is prepared for cold weather. Cold-weather crops include Indian millet, wheat, gram, lentils, and oilseeds like groundnut safflower, niger seed, and linseed. This mixed crop grows in poor soils but does not thrive in rich soils where bajri flourishes. Wheat, in particular, grows best in rich black soil. In some alluvial lands, vegetables and castor plants are grown alongside the usual late crops.

Garden crops such as vegetables, chilies, onions, garlic, guavas, limes, sugarcane, betel leaves, grapes, plantains, and gram. The best garden tillage can be found in parts of Parner, Nagar, Shevgaon, and Jamkhed.

Agricultural Communities

According to the 2011 Census, at the time, about 46% of the total population were engaged in agriculture, with a higher percentage of women (49%) participating in the activity compared to men (43%). The Ahilyanagar district Gazetteer (1976) provides insight into the various communities involved in agriculture. The Bangars, for example, are landowners, cultivators, and field laborers. Kunbis, found throughout the district, especially in the western Akole division, typically own land and work as cultivators. Malis, or gardeners, are present across the district and are divided into four groups based on their specialization—Phul Malis (flower growers), Jire Malis (cumin-seed growers), Haldi Malis (turmeric growers), and Kacha Malis (cotton-braid weavers). They primarily serve as agricultural laborers. Other landowning agricultural groups include the Pahadis, Rajputs, and Deshastha Brahmins.

The Lonaris, a community of salt makers, are found in all subdivisions except Akole and Rahuri, with their name derived from "Lonar," meaning salt in the local language. Agricultural labor is also provided by the Bhois, a fishing community residing in riverbank towns and villages, except in Akole and Kopargaon. Several other groups contribute to agriculture, including the Kamathis, Lamans (also known as Charan Vanjaris), and Mangs. Among the Muslim communities, the Bagbans (fruit vendors) and Pinjaras (cotton cleaners) also engaged in agricultural activities.

Labor

For most farming activities, labor is typically provided by the farmer's own family. Routine tasks like irrigation are handled by family members, while additional laborers are hired from the local area based on seasonal demand or specific work needs. A unique practice in the village, known as 'Savad,' involves mutual labor exchange instead of monetary payment. For example, if Farmer B works for three days on Farmer A's field, Farmer A will later work for three days on Farmer B's field to repay the labor.

Agricultural labor is generally sourced locally, with villagers working on nearby farms daily. If no work is available in their village, they often travel to neighboring villages to find employment. Additionally, many laborers from regions such as Marathwada, especially the Beed district, and the Vidarbha region, come to Ahilyanagar for farm work. Conversely, after the main harvest season, many villagers, particularly from the Akole region of Ahilyanagar district, migrate to urban areas like Mumbai (Bhiwandi and Thane) in search of employment.

For orchard crops like grapes, pomegranates, custard apples, and guavas, farmers often hire laborers from outside the region, including from states like Bihar, due to the specialized nature of the work.

Pioneering Women Agriculturalists

Shailaja Popatlal Navander

According to a news article written by Steve Herman (2014), Shailaja Popatlal Navander from Umbri Balapur village in Sangamner Taluka was one of five farmers from the Asia-Pacific region recognized by a U.N. agency on World Food Day for her innovation in family agriculture. Along with her husband, Shailaja began farming on seven and a half hectares, initially focusing on wheat as a cash crop. While they saw initial success, monocropping soon depleted the soil of essential nutrients, making chemical fertilizers less effective and reducing yields, which led to mounting debts.

Determined to change this, Shailaja sought help from agricultural workers who taught her organic farming methods and environmentally friendly practices. She and her husband learned to use natural compost and pesticides, level their land, and implement irrigation systems. Today, they grow a variety of crops, including grains, sugarcane, flowers, fruits, and vegetables, restoring the fertility of their soil.

Shailaja is also making a broader impact by empowering women in her community. She organized thrift groups and taught women organic farming techniques. Her leadership has earned her a position on the State Farmers Advisory Committee for Maharashtra, where she continues to influence sustainable farming practices.

Padma Shri Rahibai Popere

Rahibai Soma Popere was born in 1964 in Ahilyanagar district, She is a farmer and conservationist, renowned for encouraging other farmers to return to growing native crop varieties. She also helps self-help groups prepare hyacinth beans. In 2018, she was named one of the BBC's "100 Women" and is affectionately referred to as the "Seed Mother" by scientist Raghunath Mashelkar (former Director General of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)) for her work in seed conservation. Hailing from Kombhalne village in the Akole taluka of Ahilyanagar district, Rahibai belongs to the Mahadev Koli community. Despite having no formal education, her lifelong experience working on farms has given her an extensive understanding of crop diversity. On her land, she grows 17 different crops.

According to an article published by YourStory (2017), Rahibai has managed to conserve various native seeds like 15 types of rice, 60 types of vegetables, 9 types of pigeon peas, and many other oilseeds. In 2017, the BAIF Development Research Foundation recognized her efforts, noting that the gardens she supports provide enough food to sustain a family for an entire year. She received the country's fourth-highest civilian award from then-President Ram Nath Kovind in January 2015 for her significant contribution to agriculture.

Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

Hurda

Hurda is a local festive picnic popular in regions that grow Jowar (Great Millet). It is celebrated after the harvesting of Jowar is completed. A few stalks of the crop are threshed on the spot, and then this threshed grain is roasted over a fireplace to make a delicious snack, which is locally known as "hurda". This snack is usually consumed by the farmer’s family on the farm itself.

Sugarcane Tiger/Wagh

Just before the sugarcane harvest starts, a tiger-like figure (called Wagh) is made using the sugarcane leaf, this figure is then worshiped. People ceremoniously crack open a coconut and carry gulal with them for this ritual. After this, the mature sugarcane is harvested.

Types of Farming

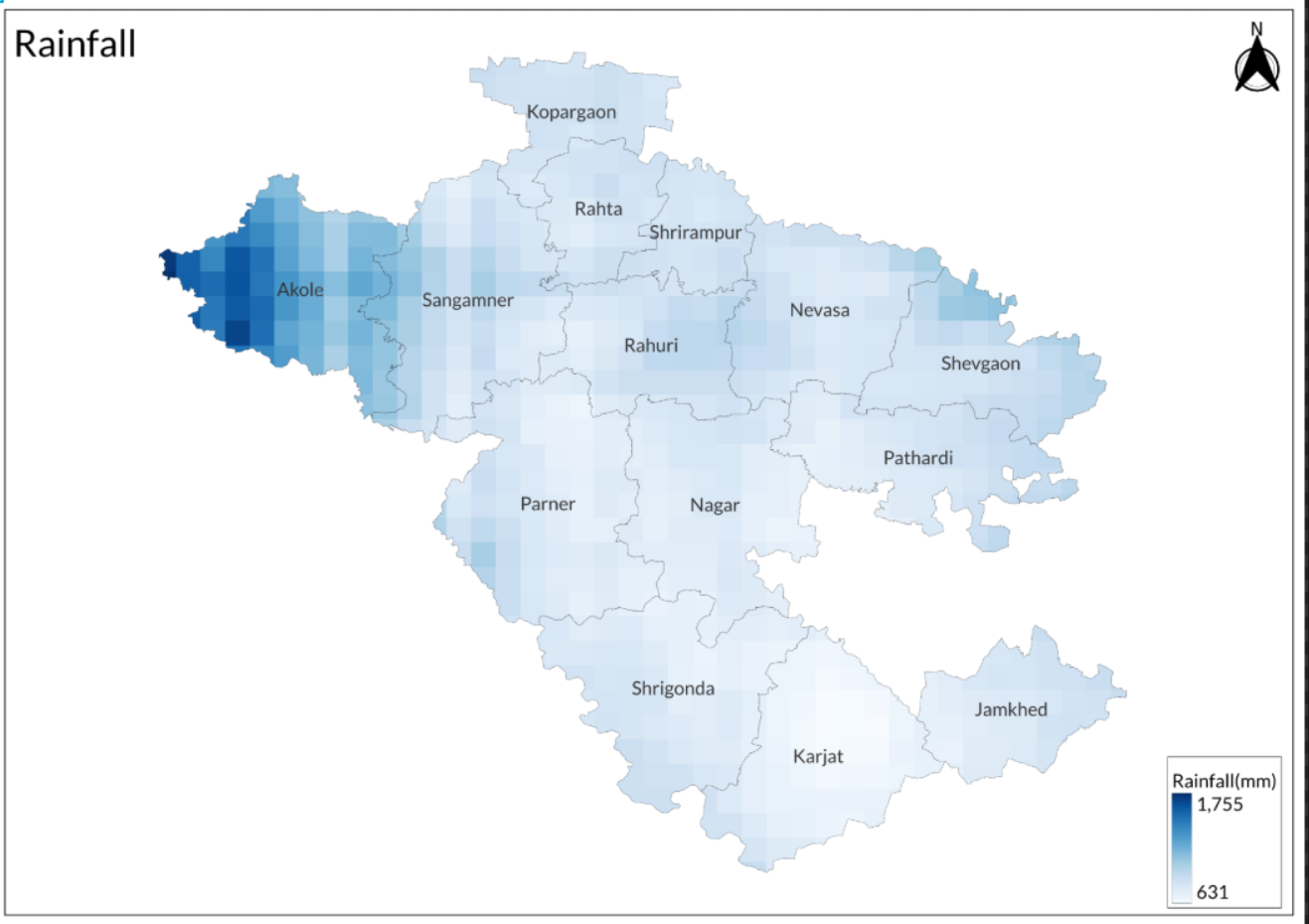

Ahilyanagar entirely lies in the Deccan Plateau. According to the Ahilyanagar District Gazetteer of 1976, the soils in the district can generally be classified into three groups, viz., black or kali, red or tambat, and laterite, and the gray of inferior quality locally known as barad, including white or pandhari. Of these, barad soils are very poor in fertility. Near the Pravara and Godavari rivers, white tracts of deep, rich lands are found. The rains usually start in the second week of June and last till the end of September. Agriculture in the district depends mainly on the rainfall from the southwest monsoon. The distribution of rainfall is most uneven. The major part of precipitation is experienced in the western portions of Akole taluka, whereas rains in the southern part of the district are erratic.

Farmers in the talukas of Shrigonda, Parner, Akole, Sangamner, and Rahta typically cultivate one sugarcane crop annually, while Sangamner is known for large-scale tomato cultivation. In the Takli Dhokeshwar and Nighoj regions of Parner Taluka, green peas are specifically grown, with some farmers also cultivating sunflowers, bajri, onions, and other cereals, primarily during the rainy season. Cultivation continues during the Rabi season as well.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Traditional agricultural practices are still followed in many villages of the Ahilyanagar district. Farmers in these areas continue to use bullocks for various tasks such as plowing, sowing, and harrowing, instead of modern machinery like tractors. This reflects a deep connection to traditional methods of farming, which have been passed down through generations. Another important practice is the use of "Shenkhat," manure made from cow dung, instead of chemical fertilizers. Farmers also prefer biofertilizers, which help maintain soil fertility and health, over chemical alternatives.

Kandyache Got

In most villages, farmers grow their onion seedlings rather than purchasing them from shops or nurseries. Known locally as Kandyache Got, these seedlings are grown directly in the field and later transplanted to onion farms or beds. Additionally, farmers often use non-hybrid varieties of seeds, opting for naturally pollinated crops instead of hybrid seeds created through artificial cross-pollination. These practices reflect a preference for sustainable and organic farming techniques over modern industrial methods.

Dahli/Kumri (Kumari) Cultivation

In the western hilly regions, a farming technique called dalhi or kumri is practiced. This method was primarily used on small plots of land located on steep hillsides. The process begins during the cold weather season by clearing the brushwood and trimming the branches of large trees. By the end of the hot weather, the fallen branches have dried up. They are then set on fire, simultaneously clearing the ground and providing natural fertilizer. After rainfall, the surface is loosened using a hoe or kudal, and the seeds are sown in the ashes. The crops, including grains like nagli, vari, and sava, are allowed to grow without being transplanted. Sometimes, the land can support a second crop the following year, but to cultivate it again, a resting period of six to ten years is necessary to allow the brushwood to regrow. While this practice continued in private fields, due to the damage caused by it to forests, the practice has seen a decline.

Use of Technology

Tractors are widely used in agriculture for tasks such as plowing, using fertilizer seed-cum drills, threshing, harvesting wheat, harrowing, and operating tractor-mounted sprayers and blowers. Technologies like spaced transplanting (STP) and various tractor-drawn implements help reduce manual labor, save time, and require less manpower. However, not all farmers adopt these technologies. Some avoid using tractors and heavy machinery due to concerns that excessive use can harm the soil's fertility and structure. Additionally, high machinery costs and the expense of implementation make them unaffordable for small and marginal farmers, especially those with small landholdings or those farming on challenging terrain, such as mountainous regions.

Today, bullock-based farming has been largely replaced by tractor-drawn farming, with the majority of farmers owning tractors and machinery. However, there remains a significant gap between the technology recommended by scientists and agricultural institutions and the farming practices used. Many farmers continue to rely on traditional methods and are hesitant to adopt newer techniques.

Drip Irrigation and Sprinkler Irrigation

The most commonly used irrigation system in farms is drip irrigation, which covers a significant portion of the agricultural area in the Ahilyanagar district. This system offers several advantages, such as conserving water, improving soil biological activity, and reducing weed growth. The sprinkler irrigation system is also used on some farms, though it is less widespread. In many rural areas, traditional sources of irrigation like wells, borewells, farm ponds, and lakes remain the primary sources of water. The water in these sources is utilised with the help of water pumps.

Droughts in Marathwada: Challenges and Government Initiatives

According to an analysis done by CEEW (2022), the frequency and intensity of extreme droughts in Ahilyanagar district have increased fourfold since 1970. The district experienced severe droughts in 2005, 2007, 2013, and 2016, leaving its people and agriculture deeply affected. In recent years, water shortages have worsened due to unpredictable and declining rainfall, making farming increasingly unviable. However, many farmers have found ways to adapt to these challenges. With the support of organizations such as Panlot and NABARD, they have implemented watershed management and more efficient cropping techniques. Some farmers have also started burying diffusers in the soil, particularly for horticultural crops, to manage water more effectively.

NABARD has launched the Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) project in Ahilyanagar district with a fund of more than 29 lakhs. The project's goal is to develop knowledge, strategies, and approaches to help vulnerable communities cope with and adapt to the impacts of climate change. Covering more than 25 villages with a combined population of over 23,000 people, the project employs a knowledge-driven, multi-disciplinary, and participatory approach. It focuses on watershed-based ecosystem management, integrated water resources management, and adaptive sustainable agriculture. Additionally, it provides localized, crop-specific agromet advisories and promotes biodiversity conservation, renewable energy, and institutional development. The project also emphasizes capacity building, community empowerment, the creation of tool kits, training modules, applied research, development communication, and policy engagement.

Institutional Infrastructure

According to the 2023-24 NABARD’s Potential Linked Credit Plan (PLCP) report, Ahilyanagar has a well-developed agricultural infrastructure, including 14 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 42 godowns, 19 cold storage facilities, 13 soil testing centers, 69 plantation nurseries, 30 farmers' clubs, and approximately 2,500 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. Additionally, there are two Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) supporting agricultural extension services in the region.

Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth

The Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth in Rahuri was established on 29 March, 1968, and has been operational since October 1969. The university is affiliated with numerous agricultural colleges and offers a wide range of academic programs. These include diplomas in agricultural technology and polytechnics, bachelor's degrees in Biotechnology, Food Technology, Agricultural Engineering, and Animal Husbandry, as well as B.Sc. degrees in Horticulture and Agriculture. The university also provides M.Sc. and Ph.D. programs in various agricultural disciplines.

Moreover, the university hosts a State-Level Biotechnology Center, which offers an M.Sc. program in Agricultural Biotechnology, with an intake capacity of 8 students per year.

Cooperative societies

Cooperative banks are essential to the agricultural economy, providing loans to farmers and dairy owners that enable critical investments in their operations. The district is home to several such cooperative societies. Key institutions include the Ahilyanagar District Central Cooperative Bank (ADCC Bank), Shriram Sahakari Sakhar Karkhana Ltd., Vighnahar Cooperative Sugar Factory Ltd., Sangamner Taluka Sahakari Dudh Utpadak Sangh Ltd. (Sangamner Dairy), Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS), and the Ahilyanagar District Cooperative Federation. For instance, the Ahilyanagar District Central Cooperative Bank (ADCC) disburses short-term crop loans to farmers through primary service cooperative societies under the government's Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme.

Farmers' Producers Organizations (FPOs)

The concept of Farmers Producers Organizations (FPOs) is gaining popularity among farming communities due to its significance. To form an FPO, a minimum of 15-20 groups is required, with each group consisting of 20 members, all of whom must be growers of a particular commodity. Currently, five FPOs have started operating in tehsils such as Newasa, Shrirampur, Rahata, Sangamner, and Kopargaon in Ahilyanagar district.

The first FPO, Adarsh FPO, was established in Pimpri Lauki village of Sangamner tehsil. The organization has set up a business office and started providing information to its 320 farmer members. Selected members underwent training in production technology, processing, and marketing. These trained farmers now share their knowledge and skills with other farmers, focusing on various agricultural technologies.

In addition to lime-based activities, the FPO is involved in red gram (pigeon pea) production. Each member cultivates red gram on one to two acres of land, primarily for green pod production. These green pods are mainly marketed in Gujarat, with earnings ranging from 30,000 to 45,000 rupees per acre. To enhance production and marketing, the FPO supports its members by supplying inputs, providing marketing assistance, and sharing information on various farming technologies.

Market Structure: APMCs

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1 |

Ahilyanagar |

1954 |

Bhausaheb Nanasaheb Bothe |

NA |

|

2 |

Akole |

1988 |

Bhanudas Tikande |

NA |

|

3 |

Jamkhed |

1960 |

Sharad Pandit Karle |

4 |

|

4 |

Karjat (Nager) |

1984 |

Kakasahb Laxman Tapkir |

NA |

|

5 |

Kopargaon |

1949 |

Sahebrao Rohom |

25 |

|

6 |

Newasa |

1960 |

Kadubal Baburao Kardile |

5 |

|

7 |

Parner |

1981 |

Babaji Bhimaji Tarate |

1 |

|

8 |

Pathardi |

1955 |

Subhash Rabhaji Barde |

1 |

|

9 |

Rahata |

2001 |

Dnyaneshwar Gangadhar Gondkar |

5 |

|

10 |

Rahuri |

1950 |

Arun Baburao Tanpure |

9 |

|

11 |

Sangamner |

1959 |

Shankarrao Hanumanta Khemnar |

2 |

|

12 |

Shevgaon |

1955 |

Ekanatha Dinakara Kasal |

18 |

|

13 |

Shrigonda |

1960 |

Dhansing Vitthalrao Bhoyte |

9 |

|

14 |

Shrirampur |

1950 |

Nanasaheb Punjaji Pawar |

22 |

Farmers Issues

Farmers in Ahilyanagar face numerous challenges that are affecting their agricultural productivity and livelihoods.

One of the key issues is the increasing cost of inputs. The prices of seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers continue to rise, making it difficult for farmers to afford these essential products. This is especially problematic for the majority of farmers in the district, as about 61% have land holdings of 1 hectare or less, according to NABARD’s PLCP report (2023-24). These small-scale farmers must invest significant amounts of capital to purchase inputs, yet due to unpredictable climatic conditions, their yields are often decreasing. As a result, the returns they receive are often not enough to justify the high input costs, leaving them dissatisfied.

In addition to rising input costs, farmers are facing a decrease in yield and crop loss due to erratic weather patterns. Unpredictable rainfall, extreme temperatures, and other unsuitable weather conditions are causing crops to fail. This situation is especially tough on small farmers, who rely heavily on consistent yields to sustain their livelihoods.

Water availability is another pressing concern. In recent years, the district has experienced severe water shortages due to unpredictable and declining rainfall. According to an analysis by CEEW, the frequency and intensity of extreme droughts in Ahilyanagar have increased fourfold since 1970. This makes agriculture increasingly unviable, as many farmers struggle to secure enough water to sustain their crops.

Labor availability and rising labor costs further compound the difficulties faced by farmers. One of the major issues is the unavailability of labor, coupled with the increased wages demanded by workers. Male laborers now charge around 500 rupees per day, while female laborers charge 300 rupees per day for farm work. This escalation in labor costs puts additional financial strain on smallholder farmers, who are already struggling with high input costs and uncertain yields.

Together, these challenges make it increasingly difficult for the farmers of Ahilyanagar, particularly those with small landholdings, to maintain sustainable and profitable farming operations.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Ahmednagar.gov.in. Geographical Informationhttps://ahmednagar.nic.in/en/about-district/…

Disha Ahluwalia. 2024. Daimabad was home to skilled agriculturalists—even before the Harappans’ cultural influence. ThePrint.in.https://theprint.in/opinion/daimabad-home-to…

Gazetteers Department. 1976. District Gazetteers, Ahmadnagar District. Government of Maharashtra.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

ICAR.MAHARASHTRA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: AHILYANAGAR. ICAR - CRIDA - NICRA.https://www.icar-crida.res.in/CP/Maharastra/…

Lifestyle Desk. 2020. कम पानी में अधिक फसल देने वाला बीज बैंक बनाने वाली राहीबाई स्कूल नहीं गईं लेकिन वैज्ञानिकों ने इनके ज्ञान का लोहा माना. Dainik Bhaskar.https://www.bhaskar.com/women/lifestyle/news…

Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth (Agriculture University), Rahuri.https://mpkv.ac.in/

NABARD. 2023-24.Potential Linked Credit Plan: Ahmednagar. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/te…

NABARD. Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) Project in Maharashtra.https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/Fi…

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. 2011. Census of India. Government of India.http://censusindia.gov.in

Shawn Sebastian. 2022. Climate Smart Agriculture. How an Ahmednagar farmer is adapting to drought. CEEW..https://www.ceew.in/how-ahmednagar-farmer-is…

Steve Herman. 2014. Those Who Feed Asia Constitute Most of Region’s Hungry and Poor. VOA News.https://www.voanews.com/amp/those-who-feed-a…

Your Story team. 2017. Meet Rahibai Soma Popere: the Seed Mother of Maharashtra. Your Story..https://yourstory.com/2017/09/rahibai-soma-p…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.