Contents

- Healthcare Infrastructure

- The Three-Tiered Structure of the District

- Medical Education & Research

- Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS)

- Vithalrao Vikhe Patil Foundation’s Medical College

- Age-Old Practices & Remedies

- GS Gune Ayurved College

- NGOS & Initiatives

- The Evolution of Public Health Services in the District

- Sanitation | Public Toilets & Cleanliness

- Graphs

- Healthcare Facilities and Services

- A. Public and Govt-Aided Medical Facilities

- B. Private Healthcare Facilities

- C. Approved vs Working Anganwadi

- D. Anganwadi Building Types

- E. Anganwadi Workers

- F. Patients in In-Patients Department

- G. Patients in Outpatients Department

- H. Outpatient-to-Inpatient Ratio

- I. Patients Treated in Public Facilities

- J. Operations Conducted

- K. Hysterectomies Performed

- L. Share of Households with Access to Health Amenities

- Morbidity and Mortality

- A. Reported Deaths

- B. Cause of Death

- C. Reported Child and Infant Deaths

- D. Reported Infant Deaths

- E. Select Causes of Infant Death

- F. Number of Children Diseased

- G. Population with High Blood Sugar

- H. Population with Very High Blood Sugar

- I. Population with Mildly Elevated Blood Pressure

- J. Population with Moderately or Severely High Hypertension

- K. Women Examined for Cancer

- L. Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption

- Maternal and Newborn Health

- A. Reported Deliveries

- B. Institutional Births: Public vs Private

- C. Home Births: Skilled vs Non-Skilled Attendants

- D. Live Birth Rate

- E. Still Birth Rate

- F. Maternal Deaths

- G. Registered Births

- H. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- I. Institutional Deliveries through C-Section

- J. Deliveries through C-Section: Public vs Private Facilities

- K. Reported Abortions

- L. Medical Terminations of Pregnancy: Public vs Private

- M. MTPs in Public Institutions before and after 12 Weeks

- N. Average Out of Pocket Expenditure per Delivery in Public Health Facilities

- O. Registrations for Antenatal Care

- P. Antenatal Care Registrations Done in First Trimester

- Q. Iron Folic Acid Consumption Among Pregnant Women

- R. Access to Postnatal Care from Health Personnel Within 2 Days of Delivery

- S. Children Breastfed within One Hour of Birth

- T. Children (6-23 months) Receiving an Adequate Diet

- U. Sex Ratio at Birth

- V. Births Registered with Civil Authority

- W. Institutional Deliveries through C-section

- X. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- Family Planning

- A. Population Using Family Planning Methods

- B. Usage Rate of Select Family Planning Methods

- C. Sterilizations Conducted (Public vs Private Facilities)

- D. Vasectomies

- E. Tubectomies

- F. Contraceptives Distributed

- G. IUD Insertions: Public vs Private

- H. Female Sterilization Rate

- I. Women’s Unmet Need for Family Planning

- J. Fertile Couples in Family Welfare Programs

- K. Family Welfare Centers

- L. Progress of Family Welfare Programs

- Immunization

- A. Vaccinations under the Maternal and Childcare Program

- B. Infants Given the Oral Polio Vaccine

- C. Infants Given the Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) Vaccine

- D. Infants Given Hepatitis Vaccine (Birth Dose)

- E. Infants Given the Pentavalent Vaccines

- F. Infants Given the Measles or Measles Rubella Vaccines

- G. Infants Given the Rotavirus Vaccines

- H. Fully Immunized Children

- I. Adverse Effects of Immunization

- J. Percentage of Children Fully Immunized

- K. Vaccination Rate (Children Aged 12 to 23 months)

- L. Children Primarily Vaccinated in (Public vs Private Health Facilities)

- Nutrition

- A. Children with Nutritional Deficits or Excess

- B. Population Overweight or Obese

- C. Population with Low BMI

- D. Prevalence of Anaemia

- E. Moderately Anaemic Women

- F. Women with Severe Anaemia being Treated at an Institution

- G. Malnourishment Among Infants in Anganwadis

- Sources

AHILYANAGAR

Health

Last updated on 4 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Ahilyanagar’s healthcare landscape, like many other regions across India, is shaped by a mix of indigenous and Western medical practices. For centuries, indigenous knowledge and treatments provided by practitioners such as hakims and vaidyas have formed the foundation of healthcare in the region. Notably, the region’s medical heritage bears a significant connection to medieval scholarship through Rustam Jurjani; a distinguished Persian physician who served in the courts of Malik Ahmad I and Burhan Shah, rulers of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. Fascinatingly, his medical treatise Zakhirai-Nizamshahi (Supplies of Nizamshah) stands as an important document, offering insights into the medical practices of the medieval era.

Much of Ahilyanagar’s formal healthcare infrastructure began to take shape under colonial rule with the establishment of the Civil Hospital in 1882. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1884), before this, several grant-in-aid dispensaries were also introduced in various zillas, which were among the early efforts to build a healthcare infrastructure within the district. Over the years, the region has witnessed several significant developments in healthcare delivery. Most significantly, a groundbreaking healthcare model was initiated in the Jamkhed taluka of the district, which became recognized and commended by the World Health Organization (WHO). This transformative model of participatory healthcare, called the CHRP (Comprehensive Rural Health Project), engaged local communities in ways that redefined rural healthcare delivery.

Healthcare Infrastructure

Ahilyanagar’s healthcare infrastructure aligns with the broader Indian model, which is characterized by a multi-tiered system comprising both public and private sectors. Currently, the public healthcare system is tiered into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. Primary care is provided through Sub Centres and Primary Health Centres (PHCs), while secondary care is managed by Community Health Centres (CHCs) and Sub-District hospitals. Tertiary care, the highest level, includes Medical Colleges and District Hospitals. This system has been shaped and refined over time, influenced by national healthcare reforms.

The Three-Tiered Structure of the District

Ahilyanagar’s formal healthcare infrastructure, like much of India, has its origins in the colonial era, which laid the groundwork for the system in place today. As Rama Baru explains in Missionaries in Medical Care (1999), “Allopathic medicine was introduced by the British in the mid-18th century, primarily to serve the needs of their civilian and military population.” The presence of the military in Ahilyanagar likely played a key role in the establishment of dispensaries throughout the region. Among the earliest and most significant institutions was the Civil District Hospital, established in Savedi in 1882. It remains the district’s primary government healthcare facility to this day.

While British colonial policies laid the groundwork for healthcare in Ahilyanagar, missionary efforts played a crucial role in shaping its medical landscape. The district is often referred to as the ‘Jerusalem of Maharashtra’ due to the influence of American missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries. Female missionaries, in particular, made significant contributions to both education and healthcare in the region. One enduring testament to their work is the Evangeline Booth Hospital (locally known as Dagadi Dawakhana or the Stone Hospital). Founded in 1904 by female members of the American Marathi Mission, the hospital initially focused on women’s and children’s health, establishing itself as one of the oldest medical institutions in the district.

In 1939, the Evangeline Booth Hospital expanded into a multispecialty facility under the management of the Salvation Army, a Protestant Christian church and international charitable organization. For several decades, it is noted that these two hospitals remained as the only major healthcare providers in the city area of the district.

However, this landscape began to change over time. The public health infrastructure began expanding. Additionally, in the 20th and 21st centuries, private hospitals started to emerge in Ahilyanagar, with their establishment being driven by trusts, NGOs, and locals themselves.

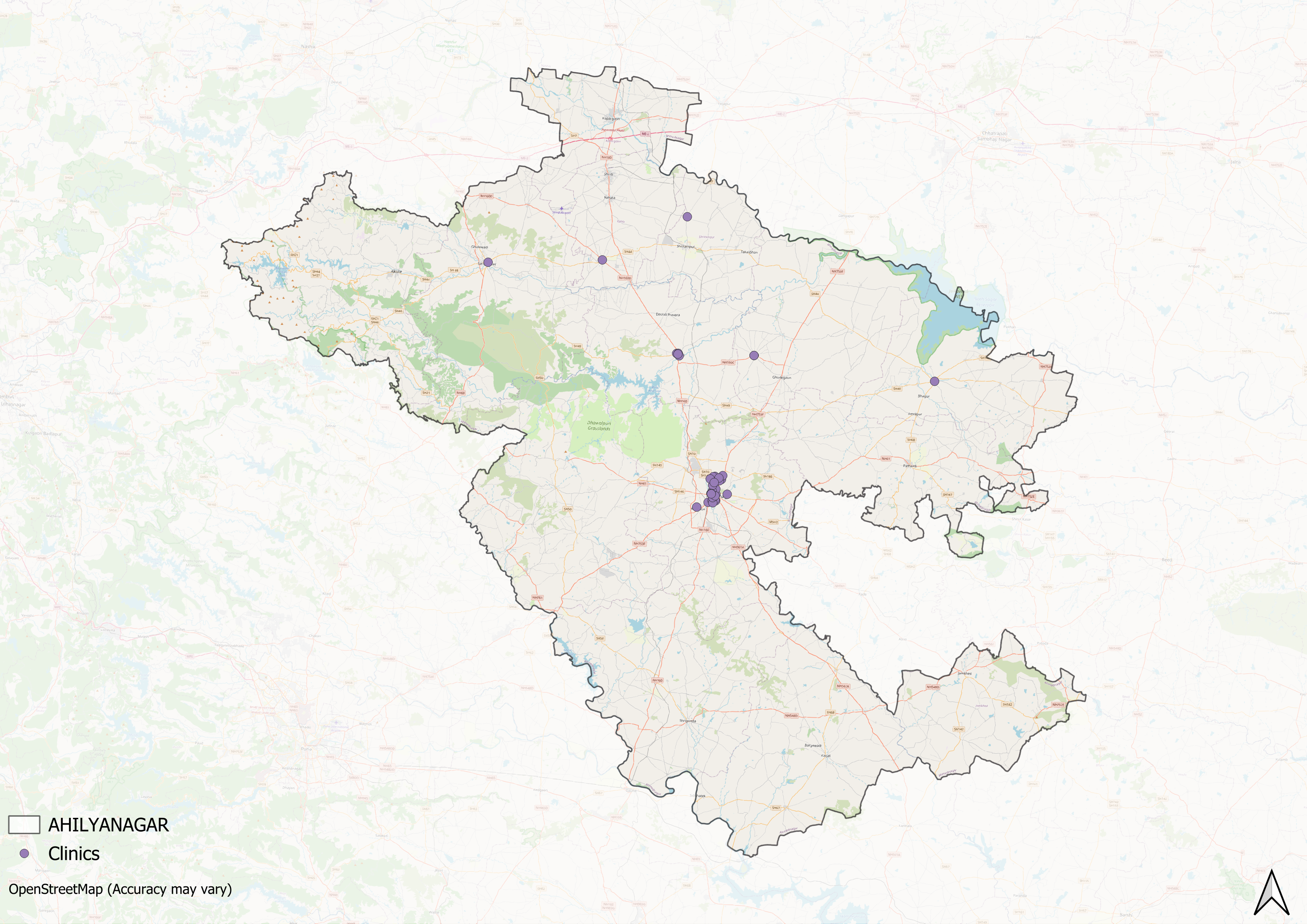

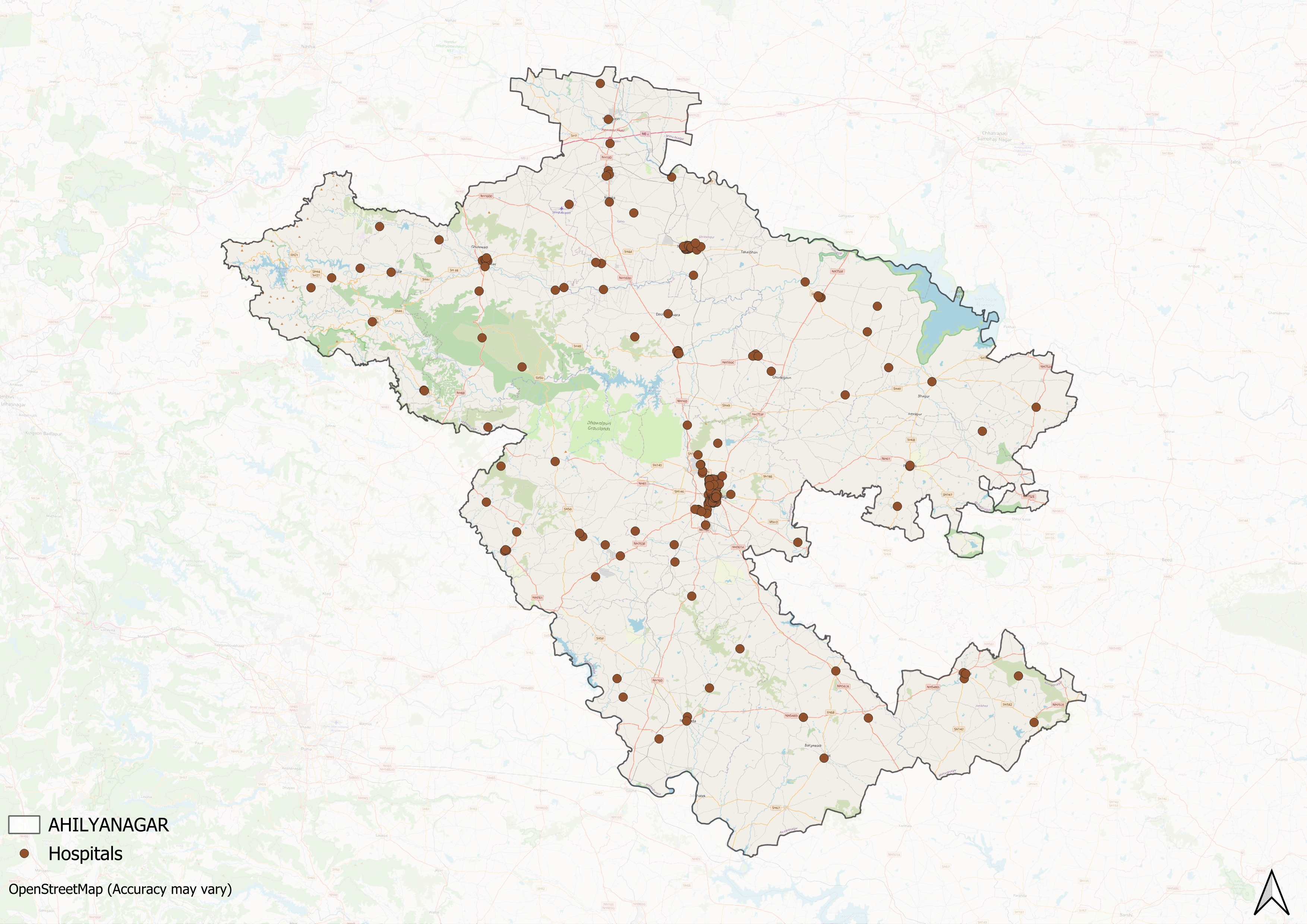

However, similar to broader patterns that can be seen across India, the district’s healthcare infrastructure has developed unevenly across geographic lines. While urban areas experienced substantial growth in private healthcare facilities, rural regions remained predominantly served by government-run hospitals, with fewer private facilities. District health reports (as recent as 2024) indicate a gradual expansion of medical infrastructure, though studies suggest this growth varies significantly between talukas, with some areas, such as Shevgaon, Akole, and Shrigonda, among others, lagging notably behind in this development of both public and private facilities.

The growth of private healthcare in the district, additionally, reflects both positive and challenging trends. While it shows increasing health awareness and local medical capacity, it also highlights gaps in the public healthcare system. This transition also raises important questions about healthcare affordability, quality, and accessibility for the district's population

In response to these challenges, hospitals aimed at minimizing costs have emerged, with NGOs and trusts playing a crucial role. The Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust Super Speciality Hospital, established in 2006, exemplifies this shift. The hospital was designed to provide affordable medical services to patients from Below Poverty Line (BPL) families and those from underserved communities.

![The Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust Super Speciality Hospital in Shirdi.[1]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/health/the-shri-saibaba-sansthan-trust-super-sp_hPlikFI.png)

This rising involvement of NGOs and trusts in healthcare underscores ongoing concerns about accessibility, quality, and affordability. These issues, which are prevalent across India, require targeted attention to ensure that healthcare is both equitable and efficient for all.

Medical Education & Research

Medical education and research are foundational to a district’s healthcare infrastructure. As Mathew George (2023) aptly highlights, medical institutions often serve a “dual purpose,” which includes educating future healthcare professionals and providing healthcare services to the local population. The medical education landscape in Ahilyanagar spans multiple healthcare traditions such as allopathy, ayurveda, and homeopathy, a feature that captures India’s pluralistic healthcare traditions.

However, surprisingly, the district notably lacks an explicitly listed government medical college despite having 14 talukas and a substantial rural population. While, according to a Times of India report (2022) plans for a government medical college are underway, currently, private institutions and government-aided colleges make up the medical education landscape of the district. Notably, among these private institutions are some significant healthcare centers, including a deemed university-status medical institute with extensive hospital facilities and research capabilities.

Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS)

One of the key private institutions in Ahilyanagar is the Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS), which is located in Loni. PIMS is a deemed-to-be University, and its status as a university allows it to offer a wide range of academic programs in the medical field.

The university includes seven constituent colleges that provide specialized education in fields such as rural healthcare (through Dr. Balasaheb Vikhe Patil Rural Medical College), dentistry (Rural Dental College), public health (School of Public Health and Social Medicine), and biotechnology (Center for Biotechnology). Students are given practical training at both Primary Health Centers (PHCs) and tertiary healthcare institutions, ensuring a broad exposure to different levels of healthcare delivery. The university offers undergraduate programs, postgraduate courses, and research opportunities, allowing students to specialize in various areas of medicine.

Vithalrao Vikhe Patil Foundation’s Medical College

The Vithalrao Vikhe Patil Foundation Medical College is a private medical school located in Vilad Ghat. Founded by the Vithalrao Vikhe Patil Foundation, the college offers a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) program and postgraduate programs in 10 medical specialties. The college is affiliated with the Maharashtra University of Health Sciences.

The college is affiliated with the Dr. Vikhe Patil Memorial Hospital, a 990-bed facility, which serves as a teaching hospital for students. In addition, the college operates an Urban Health Training Centre in Ahilyanagar and a Rural Health Training Center in Vambori, both of which provide training for undergraduate students in diverse healthcare settings.

Age-Old Practices & Remedies

Historically, before the advent of Western health care systems or the three-tiered healthcare infrastructure that exists today, people in the district relied on and made use of indigenous knowledge and medicine for their well-being. When it comes to healthcare, India, for long, has been characterized by a pluralistic health tradition. Among the many medicine systems that have a long history in India and in Ahilyanagar, as locals say, are Ayurveda and Unani.

GS Gune Ayurved College

While historical records of local medical practices in Ahilyanagar are sparse, some fascinating details survive. Interestingly, in the year 1917, a medical college dedicated to Ayurveda was established by a vaidya named Panchanan Gangadhar Shastri Gune in the district. Besides the college, Gune also formed an organization named the Ayurved Shastra Seva Mandal within Ahilyanagar city.

![GS Gune Ayurved College in Ahilyanagar.[2]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/health/gs-gune-ayurved-college-in-ahilyanagar2-7104c915.png)

The establishment of the institution is fascinating and significant for several reasons. Firstly, they offer a glimpse into the local history and figures involved with Ayurveda in the district. Secondly, this development, occurring during the colonial period, offers valuable insight into local efforts to formalize and preserve Ayurvedic practice, and is particularly notable given the political context of the time. Thirdly, at a time when Western medicine was gaining prominence, it shows how local communities actively preserved and formalized their indigenous medical traditions.

This institutionalization of Ayurvedic knowledge represents one facet of Ahilyanagar’s medical heritage. However, besides formal institutions, one of the significant yet frequently overlooked aspects of healthcare traditions includes the role of age-old practices and home-based remedies. In India, as many say, indigenous knowledge and household remedies have for long formed the basis of many family healthcare practices. These local remedies and healing methods have persisted through time through intergenerational transmission.

Historical records and local accounts indicate that “nadi pariksha” (pulse diagnosis) was widely practiced in Ahilyanagar. Locals would approach either vaidyas or hakims for medical cures and treatments that were usually herbal-based remedies. Additionally, they would provide spiritual knowledge to the patients on how to heal their bodies and minds.

This traditional knowledge passed down generationally and often orally gradually became part of local household recipes and is now commonly used without formal consultation or diagnosis. One such natural remedy is the ‘Jwaragna Kadha,’ often prepared to treat coughs and viral infections. This Kadha is made by boiling a mixture of natural and easily available ingredients such as Tulsi, Jeshtamadh, Turmeric, Mulethi, cardamomum, black pepper, and cinnamon in a cup of water until it reduces by half. The resulting brew is consumed while still hot.

Notably, even today, for many, these healing practices and knowledge continue to play a vital role in family healthcare traditions and have become part of the region’s medical heritage. The widespread use of these practices alongside contemporary medical practices demonstrates their enduring relevance.

NGOS & Initiatives

The determinants of health and health outcomes, as the World Health Organization (WHO) elaborates, are not solely shaped by more than just medical factors and healthcare services. The organization uses the term “social determinants of health (SDH)” to refer to the “non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.” These non-medical factors can be sanitation, nutrition, community well-being, or, as the WHO outlines, “income and social protection,” “food security,” access to quality healthcare, and more.

While there have been ongoing efforts to strengthen Ahilyanagar district’s healthcare infrastructure, certain areas still face challenges, particularly in addressing these broader health determinants. In response, non-governmental organizations have emerged as vital partners, working alongside public health systems to develop innovative, grassroots-level approaches that bridge these gaps.

Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP)

The Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP) is one such transformative initiative that has had a significant impact on the healthcare and health outcomes in the region. Launched in the 1970s by Dr. Rajanikant Arole and his wife Mabelle Arole, CRHP has not only addressed the pressing health issues of Jamkhed but also provided a model that has been recognized worldwide for its innovative, holistic, and community-based approach to healthcare.

The roots of the project can be traced back to the 1960s when the Aroles, having recently completed their graduation, worked at a rural voluntary hospital. It was during this time that they identified a troubling pattern: patients diagnosed and treated for preventable illnesses were often returning with the same conditions. Their observations revealed that rural health challenges extended beyond medical issues to encompass systemic problems of poverty, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to health education.

In the early 1970s, the Aroles arrived in Jamkhed, a village weighed down by poverty and lacking basic healthcare infrastructure. They quickly realized that perhaps clinical treatments alone wouldn’t address the community’s deeper health struggles. Rather than focusing solely on medical solutions, the couple created a holistic model that addressed the fundamental determinants of health such as clean water, proper nutrition, and basic sanitation— basic necessities that were out of reach for the villagers.

The Aroles perhaps understood that lasting health improvements required more than just medical care; they needed to address the foundational elements that underpinned well-being. By tackling these basic necessities, they laid the groundwork for sustainable change.

A central element of the CRHP’s success is its Village Healthcare Workers (VHWs) program. To overcome the challenge of inadequate healthcare infrastructure, the Aroles recruited local individuals, primarily women and Dalits, to serve as healthcare workers within their communities. This grassroots approach ensured that healthcare services reached the most marginalized populations while also fostering local ownership of health initiatives.

![Village healthcare workers (VHWs) of the CHRP. Source: CRHP India[3]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/health/village-healthcare-workers-vhws-of-the-c_OXgCwPo.png)

The VHWs were trained to provide essential health services, educate community members about disease prevention, and mobilize resources. Their role extended beyond clinical care to include broader public health education, especially regarding sanitation, nutrition, and preventive care.

The success of this approach became evident through significant improvements in key health indicators. As per reports, Jamkhed saw remarkable reductions in maternal and infant mortality rates, demonstrating the effectiveness of community-based, holistic healthcare solutions. These improvements caught the attention of global health organizations and influenced worldwide approaches to rural healthcare delivery.

As scholars Henry Perry and Jon Rohde (2019) note, the CRHP’s impact extended far beyond Jamkhed. The World Health Organization recognized it as a pioneering model for healthcare delivery in developing nations, featuring it prominently in their 1975 publication “Health by the People.” The project’s influence peaked at the 1978 Alma-Ata Conference, where its principles played a key role in shaping the global primary healthcare movement. The resulting Alma-Ata Declaration famously framed health as a fundamental human right and emphasized that achieving the highest possible level of health is a critical global social goal.

In addition to its long-term successes, CRHP’s infrastructure was crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. The project’s community-based framework allowed it to rapidly adapt to the crisis, working closely with local authorities to classify, diagnose, and treat COVID-19 patients in Jamkhed.

![Julia Hospital, Jamkhed. Source: CRHP India[4]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/ahilyanagar/health/julia-hospital-jamkhed-source-crhp-india_bMtYwFg.png)

During the pandemic, Julia Hospital, originally part of CRHP’s healthcare infrastructure, was repurposed to accommodate COVID-19 patients. Meanwhile, the Old Hospital was converted into designated wards for COVID-19 treatment. CRHP also established Community Centres to support vulnerable populations, further expanding its services to meet the needs of the community during a global health crisis.

The Evolution of Public Health Services in the District

Epidemics and disease outbreaks have significantly shaped public health outcomes throughout history, creating persistent challenges that communities have continuously sought to overcome. In the case of Ahilyanagar district, documented historical records indicate several key outbreaks that impacted both the population’s health and mortality rates, particularly in the late 19th century under colonial rule. During this period, the district faced widespread outbreaks of cholera, smallpox, and fevers, which contributed to high mortality rates. The colonial district Gazetteer (1884) offers a detailed account of this era, noting the prevalence of additional ailments, including conjunctivitis, skin diseases, and malaria. Moreover, the Gazetteer draws attention to a mysterious Cat Plague, which is suggested to have been interrelated with the cholera outbreaks.

The mortality data from the Gazetteer (1884) reveal that fevers were the leading cause of death in the district, accounting for approximately 64% of all fatalities. Cholera, smallpox, and bowel complaints were also significant contributors to the high death toll, underscoring the severe health challenges the district faced during this period.

By the mid-20th century, significant strides were made in controlling diseases like cholera and plague, primarily due to targeted public health campaigns. Mortality rates from these diseases declined sharply, as indicated in the Gazetteer. However, while cholera and plague became less of a concern, other diseases such as malaria and gastroenteric infections remained persistent challenges.

In the post-independence era, the Government of India launched several national programs aimed at eradicating specific diseases. Notably, the National Malaria Eradication Programme played a crucial role in reducing the burden of malaria in Ahilyanagar. From 1953 onwards, a systematic approach to malaria control was introduced, with DDT spraying implemented across the district’s talukas. According to the Gazetteer (1976), “an intensive campaign against malaria was launched in the district during the period of First Five-Year Plan under the National Malaria Eradication Programme. Under this scheme, each house in every taluka of the district was sprayed twice with DDT every year.”

Additionally, targeted efforts were made to address leprosy, with the establishment of specialized units at primary health centers. The creation of a voluntary colony for leprosy patients at Savedi, which provided a bed capacity for 100 individuals, was another significant step in managing the disease.

Sanitation | Public Toilets & Cleanliness

While public health services in the region have evolved over time, the struggle to control these outbreaks has remained constant. In 2010, a “cholera like outbreak” was reported to have occurred in Bhingar and other areas across the district. The main factors cited to have possibly caused this were “contaminated water supply” and “lack of cleanliness.” These same factors—poor sanitation and inadequate access to clean water—have been identified as recurring causes of outbreaks throughout history, highlighting the critical need for comprehensive interventions. This underscores the urgent need for preventive measures, including improved sanitation and proactive public health services, to address the root causes of outbreaks and safeguard community health.

Sanitation remains a critical issue that needs urgent attention within the district. Beyond general cleanliness, locals have frequently raised concerns about the lack of accessible public toilets, particularly in the Nagar taluka.

According to residents, this infrastructure gap creates daily challenges for both locals and visitors to the district. Women, in particular, have raised concerns about the shortage of clean and accessible toilets, which significantly limits their ability to move freely in public spaces. Some express that the absence of basic sanitation facilities, in subtle ways, forces them to even avoid traveling or going out.

Furthermore, the situation at historical monuments and market areas, residents say, clearly demonstrates this problem. Despite being centers of public gathering for both locals and tourists, these locations lack restroom facilities. This absence, as local community members emphasize, underscores the urgent need for improvements in the district’s sanitation infrastructure.

Graphs

Healthcare Facilities and Services

Morbidity and Mortality

Maternal and Newborn Health

Family Planning

Immunization

Nutrition

Sources

CHRP’s COVID-19 Programs.CHRP.https://www.crhpindia.org/covid-19

Deepak Gadekar, C. M. Bansode, Vijay Sonawane. 2024.A Geographical Study of Healthcare Infrastructure & Medical Facilities in Ahmednagar District, Maharashtra, India.Vol 9, No. 3.EPRA International Journal of Research & Development (IJRD).https://eprajournals.com/IJSR/article/12539

Foundation.Dr. Vithalrao Vikhe Patil Foundation's Medical College & Hospital.https://www.vimsmch.edu.in/Foundation

G. S. Gune Ayurved College.G.S.Gune Ayurved College,Maliwada,Ahmednagar.http://www.guneayurvedahmednagar.org/

Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency. 1884 (Reprinted in 2003, e-Book Edition 2006).Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency: Ahmadnagar District, Volume XVII.Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Henry Perry, Jon Rhode. 2019.The Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project and the Alma-Ata Vision of Primary Health Care.Vol. 109, No. 5. American Journal of Public Health (AJPH).

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/state-to-get-12-med-colleges-but-existing-ones-shortstaffed/articleshow/93719586.cmshttps://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mum…

Indian Environment Portal. 2010.Cholera-like epidemic claims one in Ahmednagar, 500 fall sick.http://admin.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/n…

Isaac Christiansen. 2017.Commodification of Healthcare and Its Consequences.Vol. 8, no. 1. World Review of Political Economy.https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13169/worlre…

M Choksi, B. Patil et al. 2016.Health systems in India.Vol 36 (Suppl 3).Journal of Perinatology.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC514…

Mathew George. 2023.The real purpose of the medical college.The Hindu.https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-r…

Prafulla Marpakwar. 2022. Maharashtra to get 12 medical colleges, but existing ones get short-staffed. The Times of India.

Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences is Deemed to be a University.Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences.https://www.pravara.com/university.html

Rama Baru. 1999. Missionaries in Medical Care. Vol. 34, No. 9.Economic and Political Weekly.https://www.jstor.org/stable/4407696

Rinchen Norbu Wangchuk. 2022.Padma Winning Doctor Couple’s Healthcare Model Has Been Replicated in 100+ Countries.The Better India.https://thebetterindia.com/275012/doctor-mab…

SA Hussain. 1993.Zakhira-e-Nizam Shahi: a medical manuscript of Nizam Shahi period.Vol. 23, No. 1.Bulletin of the Indian Institute of History of Medicine (Hyderabad).https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11639384/

Shri Sai Baba Hospital.Shri Sai Baba Sansthan Trust, Shirdi.https://sai.org.in/en/content/shri-saibaba-h…

Social determinants of health.WHO.https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-det…

Varsha Singh. 2020.Salvation Army hospital in Ahmednagar leads the battle against coronavirus.MIG.https://mediaindia.eu/society/salvation-army…

Last updated on 4 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.