Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Birds

- Forest Reserves

- Melghat Tiger Reserve

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Deforestation

- Water Pollution and Scarcity

- Climate Change Vulnerability

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Pedhi Dam Project

- Amravati Thermal Power Plant Project

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Soil Moisture (Yearly)

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- K. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- G. Relative Humidity

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- C. Wildlife Projects (Area and Expenses)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

AMRAVATI

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Amravati district, situated in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra, boasts a variety of ecosystems, including the Melghat Tiger Reserve, dense forests, and fertile agricultural lands. This diverse environment supports a rich array of biodiversity, which includes endangered species such as the Bengal tiger.

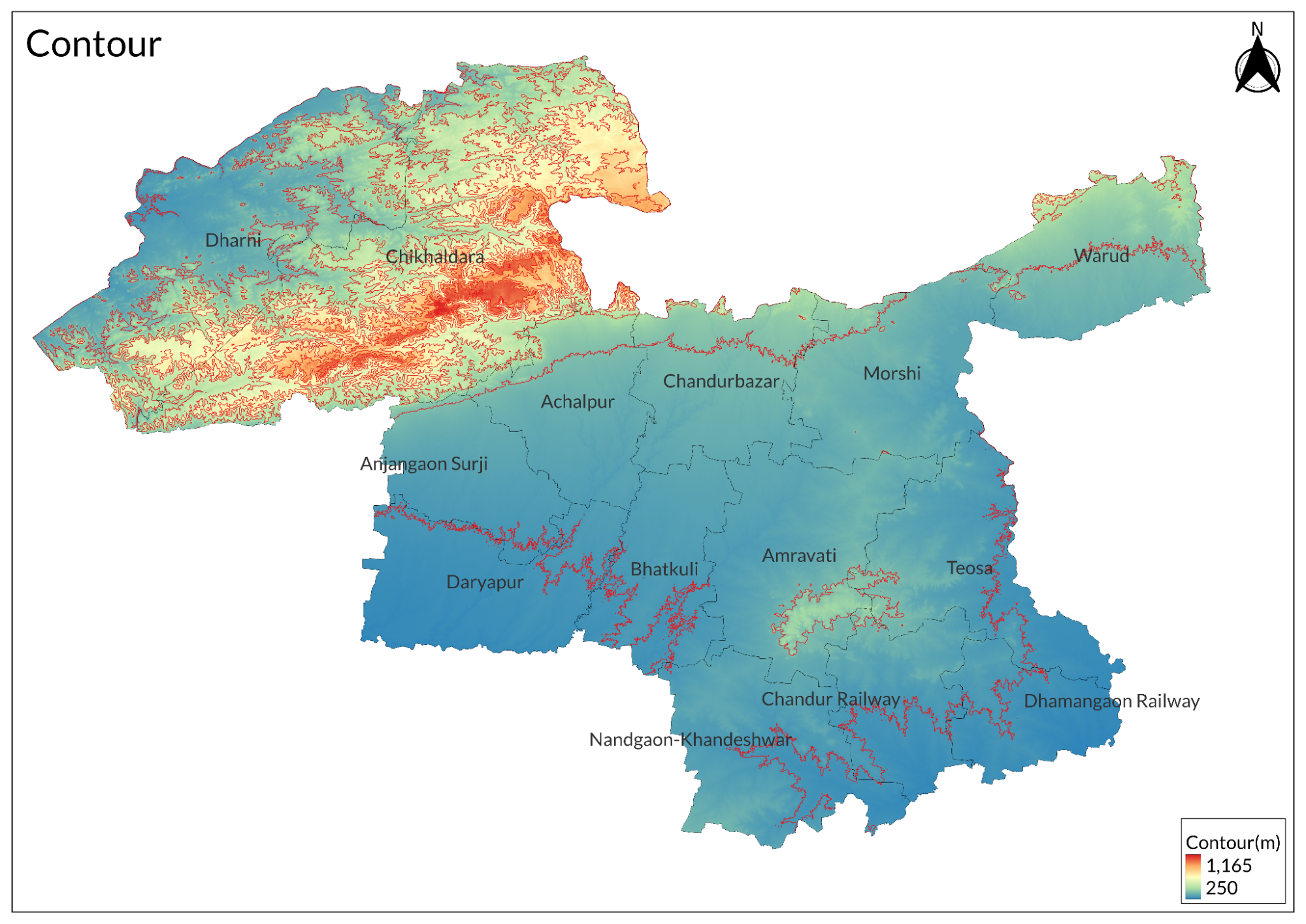

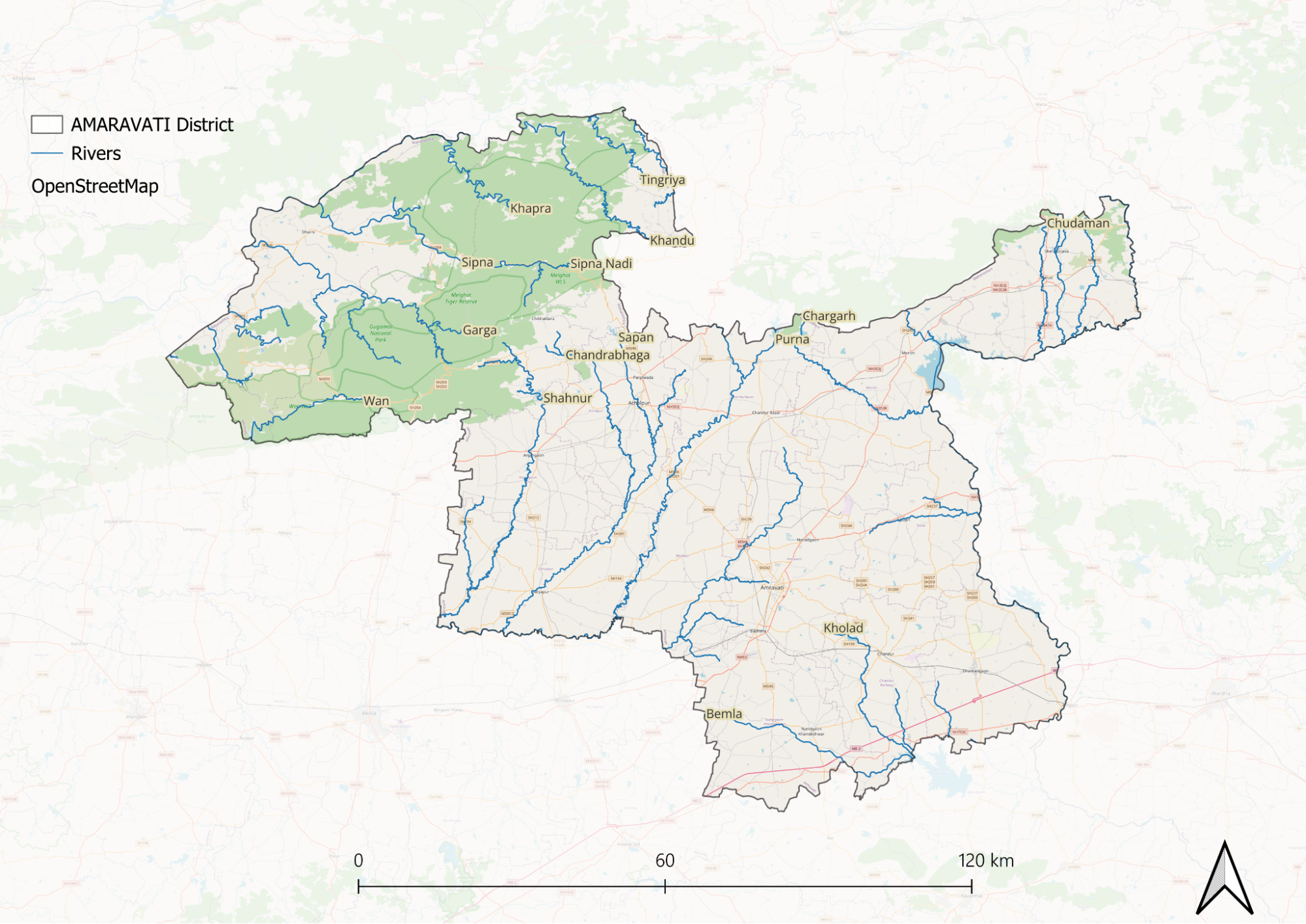

Physical Features

340 m above mean sea level, spanning an area of 12,235 sq. km, the district's name is believed to be derived from the temple of Amba Devi. Geographically, the district is divided into two main regions: the Melghat hilly area of the Satpura range in the north and the plain area in the south. To the north, the western boundary is defined by the Tapti River, while the Wardha River marks the eastern side. The Purna River flows through the center of the district. Amravati is bordered to the north by the Nimar, Betul, and Chhindwara districts of Madhya Pradesh, to the east by Nagpur and Wardha districts, and the south and west by Yavatmal, Akola, and Buldhana districts. The district is administratively divided into 14 tehsils.

The Gawilgarh hills are part of the Satpura range and are named after a fortress situated on one of their southern peaks. This range extends from the Betul District through the Melghat region to meet at the junction of the Tapti and Purna rivers in Nimar. In Melghat, the crests of this range reach an average elevation of 1,036 meters, with the highest point being Bairat plateau at 1,178 meters; Chikhaldara and Gawilgarh are slightly lower. Other notable hills include Pohara & Chirodi Hill and Maltekdi Hill. The foothills bordering the Tapti River have an average height of about 502 meters; this range consists of Deccan trap rock from the upper Cretaceous period, approximately 100 to 66 million years old. Additionally, there is a low line of trap hills near Amravati that extends eastward with an average height of 457 meters above mean sea level. Spurs from these hills extend northward for some distance, creating a stark contrast between their barrenness and the surrounding fertile land.

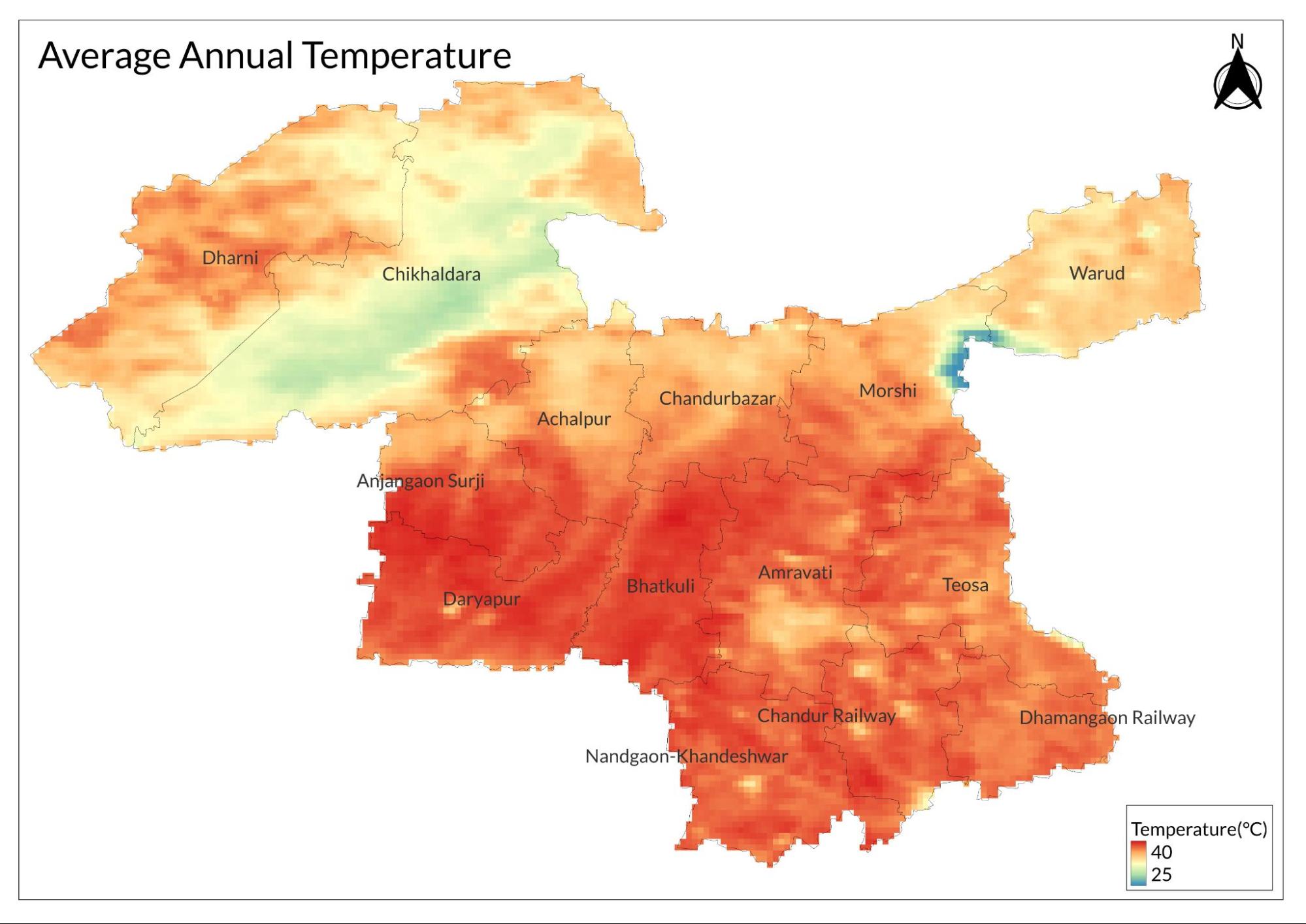

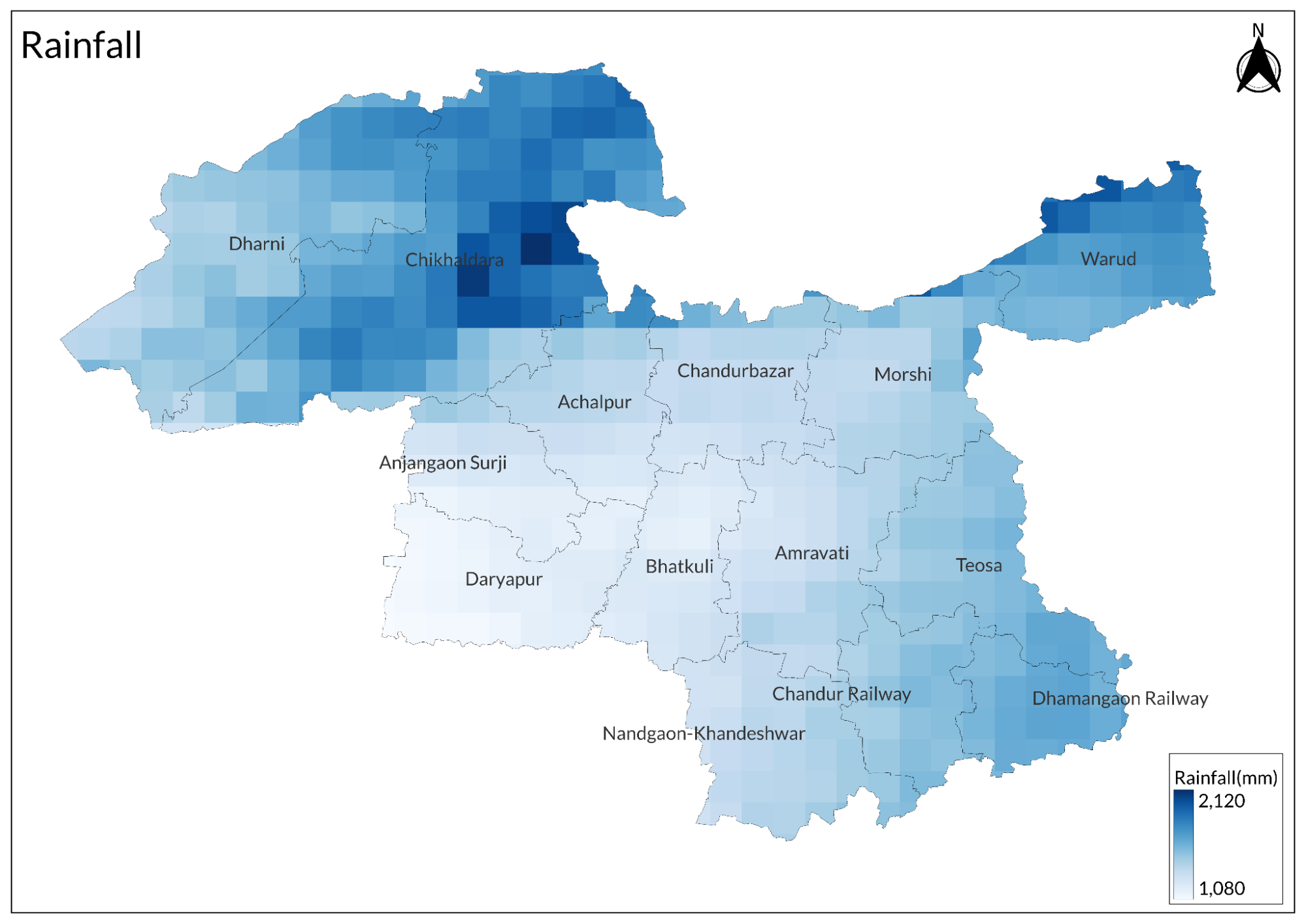

Climate

The Amravati District experiences dry weather for most of the year, with average temperatures ranging from 24°C to 32°C. The climate is characterized as hot and dry, and the year is divided into three distinct seasons: the cold season from November to February, the hot season from March to May, and the monsoon season from June to October.

The district receives rainfall primarily during the southwest monsoon, with average annual precipitation between 700 and 800 millimeters. During summer, maximum temperatures can reach up to 36°C, while winter temperatures can drop to a minimum of 5°C.

Geology

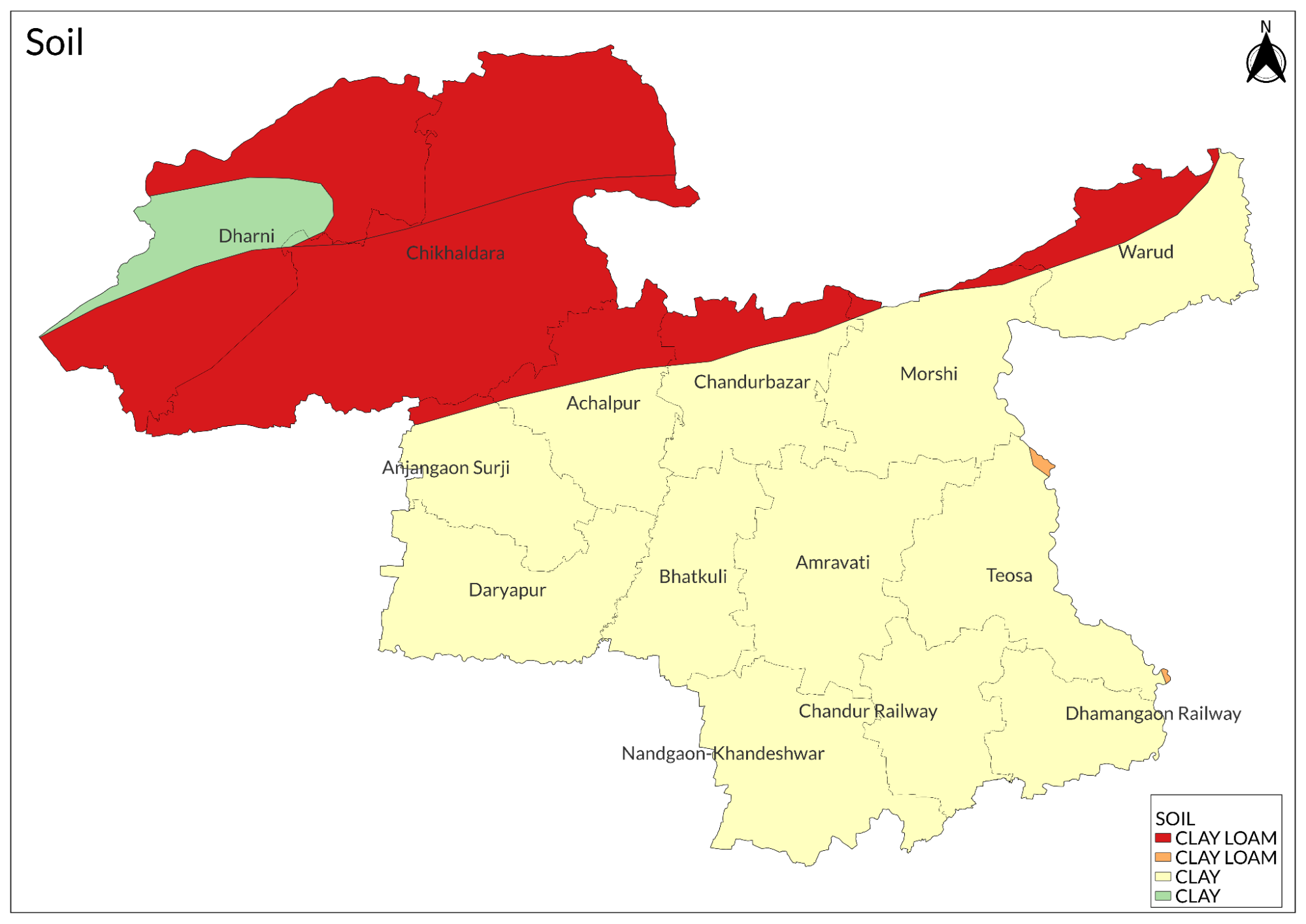

This is a geologically diverse region characterized by two main areas: the Deccan Traps, which date back to the Cretaceous period and are approximately 66 million years old, located in the north, and the Purna alluvial plain situated in the south.

Soil

The district is predominantly covered with black cotton soil, which is highly fertile and extensively used for agricultural practices. This soil type is particularly well-suited for growing crops such as cotton, pulses, and various cereals. Additionally, the Purna alluvial plain in the southern part of the district features alluvial soil, which contributes to the region's agricultural productivity.

Minerals

The only major mineral found in the region is fireclay, which is located in the Achalpur tehsil. In addition to this, various minor minerals are categorized as construction materials, including murrum, sandstones, and sand, predominantly found near Achalpur tehsil.

Rivers

The Purna River, the largest river in Amravati District, originates from the southern slopes of the Gawilgarh Hills in the Satpura range. It flows partly through Achalpur and partly through Amravati taluka before turning westward, forming a boundary between the Murtizapur and Daryapur regions as it continues into Akola District.

The Chandrabhaga River waters the western portion of Achalpur tehsil, flowing southwest past Khallar and Daryapur to join the Purna at Dhamni Khurd in Daryapur taluka. Its tributary, the Sirpan River, flows past Achalpur city, historically supplying water through a now-ruined aqueduct. Other tributaries of the Purna include the Shahnur and Bordi Rivers, which provide water to Daryapur tehsil. The Pedhi River runs from north to south through the entire length of Amravati taluka.

Several significant streams, such as the Chundamani, Bel, and Matu, traverse the Morsi tehsil for a few miles from the hills to the Wardha River, which supplies water to villages along its borders for over 80 kilometers. To the north of Melghat lies the Tapti River, which bounds the district for about 48 kilometers and receives substantial rainfall runoff from its tributaries, including the Kamda, Kapra, Sipna, and Garga rivers. Historically, local jungle inhabitants utilized this river for transporting timber to Burhanpur.

This intricate network of rivers and tributaries plays a vital role in supporting agriculture and providing water resources throughout the Amravati District.

Botany

In the Amravati District, various trees and plants thrive along roadsides and in hilly areas. Common species include neem, siris, maharuk, mango, mahua, and banyan. The siora plant is often cultivated in betel leaf gardens to support creepers and provide shade.

The coffee plants found in the Chikhaldara region were first introduced by the British and have continued to flourish for over 100 years. While wood apples are less common along field borders, they still contribute to the local flora.

Dalbergia sissoo is frequently planted as an avenue tree and originates from Northern India. Additionally, the rithia or soapnut tree is sometimes found in gardens. The shrub known as takal, which features sweet-smelling white flowers, is commonly seen in hedges.

Another notable plant is the thuar, recognized for its round green stems filled with milky sap, making it an excellent choice for hedges. Furthermore, the district boasts approximately 74 different species of bamboo, particularly located in the bamboo garden at Wadali village. This revised version enhances readability by organizing the information more logically and ensuring a smoother transition between ideas.

Wild Animals

The Amravati District is rich in diverse wildlife, including various species of monkeys, big cats such as tigers and leopards, hyenas, bears, wild pigs, deer, antelopes, and smaller mammals like foxes, squirrels, and flying squirrels. The region is also home to a variety of reptiles, including lizards and snakes like cobras and pythons. The presence of these animals reflects the district's ecological diversity, with different species inhabiting the plains, forests, and hilly terrain of the Melghat hills.

Birds

The region has a diverse bird population, featuring various species that contribute to its rich avian biodiversity. Notable species include the golden oriole, blue roller (or jay), kingfisher, and little green flycatcher. The district is also home to painted sandgrouse, rock sandgrouse, peacocks, grey partridges, jungle quails, and various quail species such as large grey, rain, and button quails.

In the Melghat region, several uncommon Indian bird varieties can be found, including the black and orange flycatcher, typically seen only in the Nilgiris and Ceylon, as well as the Malabar whistling thrush near Chikhaldara. The Ghat Black Bulbul, mentioned in the British Gazetteer of 1911, is no longer present in the district. Other notable species include the southern black-headed oriole, Indian corby, two species of green pigeons (Crocopus phoenicopteryx and C. chlorigaster), and both grey and red jungle fowls.

Forest Reserves

Melghat Tiger Reserve

Melghat Tiger Reserve, located in the Amravati district of Maharashtra, spans an area of around 2768.52 km². Located 113 km from Amravati city and situated between the Gawilgarh range of the Satpura Hills and the Tapti River, established as a wildlife sanctuary in 1967 and declared Maharashtra's first tiger reserve in 1974, Melghat is one of the country's largest tiger reserves. The name 'Melghat' means the confluence of various 'ghats' or valleys, typical of the reserve's landscape. Besides tigers, it is home to animals like the sloth bear, Indian gaur, sambar deer, leopard, nilgai, and the endangered and recently rediscovered forest owlet. The reserve is accessible by railway and plane, with the nearest railway stations being Semadoh, Kolkas, and Harisal, and the nearest airport in Nagpur, about 250 km away. While tourists can explore Melghat year-round, the monsoon season from mid-July to the end of September offers the best views. Winters can be cold with night temperatures dropping below 5°C, and summers are ideal for animal sightings. Jungle safaris are available in private and forest reserve vehicles, and accommodation is primarily run by the forest department, with some private hotels and resorts in Chikhaldara.

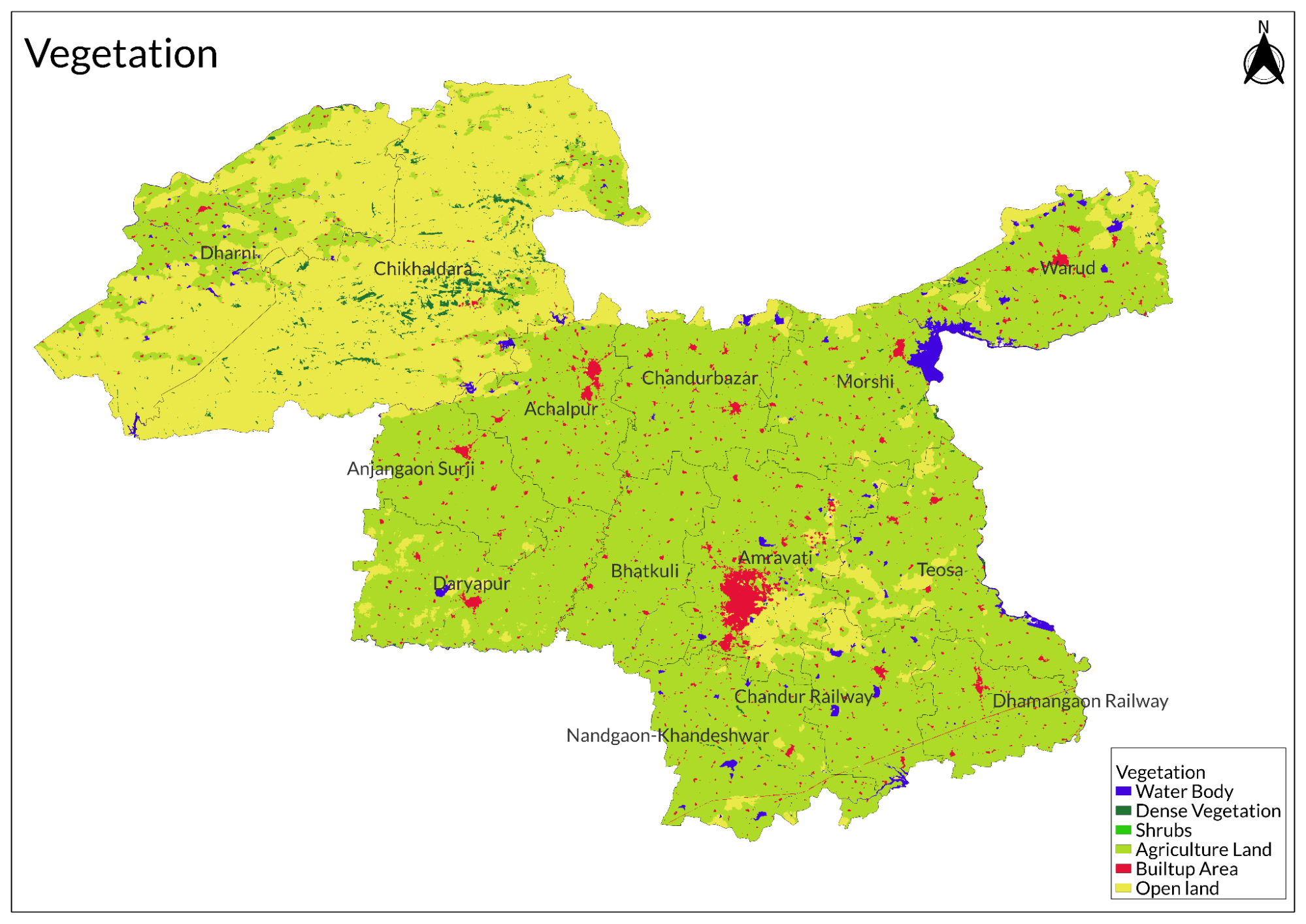

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Deforestation

Deforestation in the Amravati district has become a critical environmental concern, marked by significant reductions in forest cover over the decades. From 1978 to 2008, the district experienced a loss of 25.6 square kilometers (3.43%) of forest area. In contrast, urban settlements increased by 2.26 square kilometers (0.36%), while rural settlements expanded significantly by 25.35 square kilometers (3.40%). This shift indicates that forest degradation is closely linked to the growth of rural communities, particularly in the northern regions of Warud tahsil, where the most severe deforestation has been observed.

The situation continued to deteriorate in subsequent years; by 2010, Amravati had only 22.8 thousand hectares of tree cover, accounting for just 1.9% of its total land area. Between 2001 and 2023, the district lost an additional 376 hectares of tree cover. Specifically, in Warud Tahsil, deciduous forest cover plummeted from 57.35 square kilometers in 1977 to just 23.56 square kilometers by 2006.

The primary drivers of deforestation in Amravati include agricultural expansion, urbanization, and inadequate forest management practices. As rural populations grow and seek more land for cultivation and settlement, forests are increasingly cleared to meet these demands. The loss of tree cover not only affects biodiversity but also contributes to soil erosion, disruption of local water cycles, and climate change.

Water Pollution and Scarcity

In 2024, residents of Mariampur village in Amravati district faced a severe water crisis exacerbated by soaring temperatures and the intense summer heat. With no reliable sources of clean drinking water, villagers were compelled to collect water from polluted ponds. The only pond available to them was contaminated, forcing locals to dig pits along its banks to gather what little water they could. This laborious process required them to wake up as early as 4 AM and spend hours filling these pits, often waiting in long queues with their neighbors.

Subhash Sawalkar, a villager, described the distressing situation, highlighting the health risks posed by the polluted water. He noted that the lack of government intervention left them without water tankers or functioning taps, leading to dire consequences for their families. Many children suffered health problems due to the consumption of dirty water, prompting frequent visits to doctors.

Elderly resident Phulkai Belsare echoed these sentiments, expressing frustration over the absence of assistance from local authorities. The villagers had no access to tanker supplies and were forced to endure long waits just to collect contaminated water. Jasmine, another villager, lamented the neglect from municipal and water department officials, pointing out that while other villages had access to government taps and borewells, Mariampur was left without any reliable water source.

The situation in the Amravati district is reflective of a broader water crisis affecting the Vidarbha region, which has long struggled with climate vulnerability and inadequate water management.

Climate Change Vulnerability

Amravati district faces a range of environmental problems exacerbated by climate change and rapid urbanization. The region is particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events, which have become more frequent and severe. This includes increased temperatures and altered rainfall patterns, leading to challenges in water availability and agricultural productivity.

One significant concern is the projected increase in water consumption due to rising temperatures, which places additional stress on already limited water resources. As the population grows and urban areas expand, the water demand is expected to rise sharply, further complicating the management of this vital resource.

The impacts of climate change are not only felt in terms of water scarcity but also the broader context of environmental resilience.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Pedhi Dam Project

In the Amravati district, significant environmental conservation efforts have emerged in response to the proposed Lower Pedhi dam project, which has sparked widespread protests among local communities. Residents of Bhatkuli tehsil have expressed their strong opposition to the dam, claiming that they were misled about the formation of a committee meant to address their concerns regarding the project.

The controversy began after a prolonged dharna (sit-in protest) led by women from the area, which lasted for 20 days. Following this, they were promised a meeting with government officials, but no concrete actions were taken. Farmers like Vivekanand Mathane, a member of the Peedi Prakalp Sangram Samiti, have raised alarms about the potential negative impacts of the dam on local agriculture. They argue that the land in question is saline and unsuitable for irrigation, warning that introducing forced irrigation could render it barren within a few years.

Soil tests conducted by reputable institutions have indicated high salinity levels in the land designated for irrigation. However, the state government has countered these findings with a report from an autonomous body that claims the land is suitable for irrigation. This discrepancy has fueled further distrust among villagers, who feel that their voices are being ignored.

The protests reflect a broader concern about environmental degradation and water management in the region. Activists are not only opposing the Lower Pedhi dam but are also questioning the overall water management strategies employed by the government, particularly in light of existing challenges such as water scarcity and soil salinity.

Moreover, there are fears that the dam will exacerbate issues related to farmer suicides in an already vulnerable agricultural community

Amravati Thermal Power Plant Project

In recent years, the residents of the Amravati district actively protested against the Amravati Thermal Power Project due to significant environmental concerns. Farmers in the Vidarbha region were particularly worried that the power plant would deplete water resources from the Upper Wardha irrigation project. In June, a breakthrough occurred when Maharashtra's water resources minister, Ajit Pawar, assured local representatives that the thermal plant would not draw water from Upper Wardha but would instead recycle sewage generated by Amravati city.

While this announcement initially seemed promising and was celebrated by some activists as a victory for farmers, it quickly raised more questions than it answered. Protests resumed as details emerged about the project's water requirements. The first phase of the 2,640 MW project was projected to need 87 million cubic meters of water, far exceeding the 22-24 million cubic meters of sewage produced by Amravati. To meet its demands, additional water would also be sourced from the Kaundanyapur dam, which had not yet begun construction.

Critics like Someshwar Pusadkar, coordinator of the Sophia Hatao Sangharsha Samiti, viewed the minister's assurances as misleading. They pointed out that 24 million cubic meters of water from the Upper Wardha Irrigation Project was already reserved for industrial use, and diverting this water to the power plant would leave other industrial units in the area without the necessary resources. Pusadkar highlighted that the district had a significant irrigation backlog and that fulfilling the power plant's water needs could result in substantial irrigation losses for local farmers.

Additionally, concerns about job creation arose. The Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation had previously acquired land for industrial purposes in the area, displacing many farmers with promises of employment. Activists questioned how these promises could be met if the thermal power plant consumed most of the available water.

The community also expressed skepticism regarding assurances about ending load shedding in the district, arguing that Vidarbha produced more electricity than it consumed and did not require additional power generation from Sophia.

As discussions continued, it became evident that various stakeholders were vying for access to Amravati's limited sewage resources. The Amba nala, which received sewage discharge, irrigated local agricultural land and was linked to other projects aiming to treat and recycle this water for non-drinking purposes. With multiple claimants for this resource, including proposals for a dam project associated with Amravati's sewage, community leaders criticized the lack of coherent planning.

Farmers had long opposed projects like the Lower Pedi dam, which aimed to irrigate saline land deemed unsuitable for agriculture. With plans to divert Amba nala's water to Sophia, they argued that such projects were unnecessary and detrimental to their livelihoods.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Amol Waindeshkar. 2012.Forest Degradation in Warud Tahsil of Amravati District.Research Nebula. Academia.https://www.academia.edu/70298110/Forest_Deg…

Amravati District Administration. Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency (GSDA). Amravati District Official Website.https://amravati.gov.in/departments/gsda/

ANI. 2024.Locals in Village of Maharashtra's Amravati District Forced to Drink Dirty Water.Times of India, May 31.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/lo…

Aparna Pallavi. 2010.Misled About Water: Vidarbha's Farmers Protest Maharashtra Government's Attempt to Build Yet Another Thermal Power Plant by Depriving Them of Irrigation Water.Down to Earth, August 16.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/m…

Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). May 2019.Amaravati: Building Climate Resilience.Climate Resilience.https://www.ceew.in/publications/climate-ris…

Global Forest Watch. Forest Monitoring Dashboard - Amravati District. Global Forest Watch.https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards…

Government of Maharashtra. 1911 (Reprinted in 1983).Geology of Amravati District. Maharashtra Gazetteers.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

Nidhi Jamwal. 2007.People Feel Cheated Over Government Assurances on Pedhi Dam.Down to Earth, September 30.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/p…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.