Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

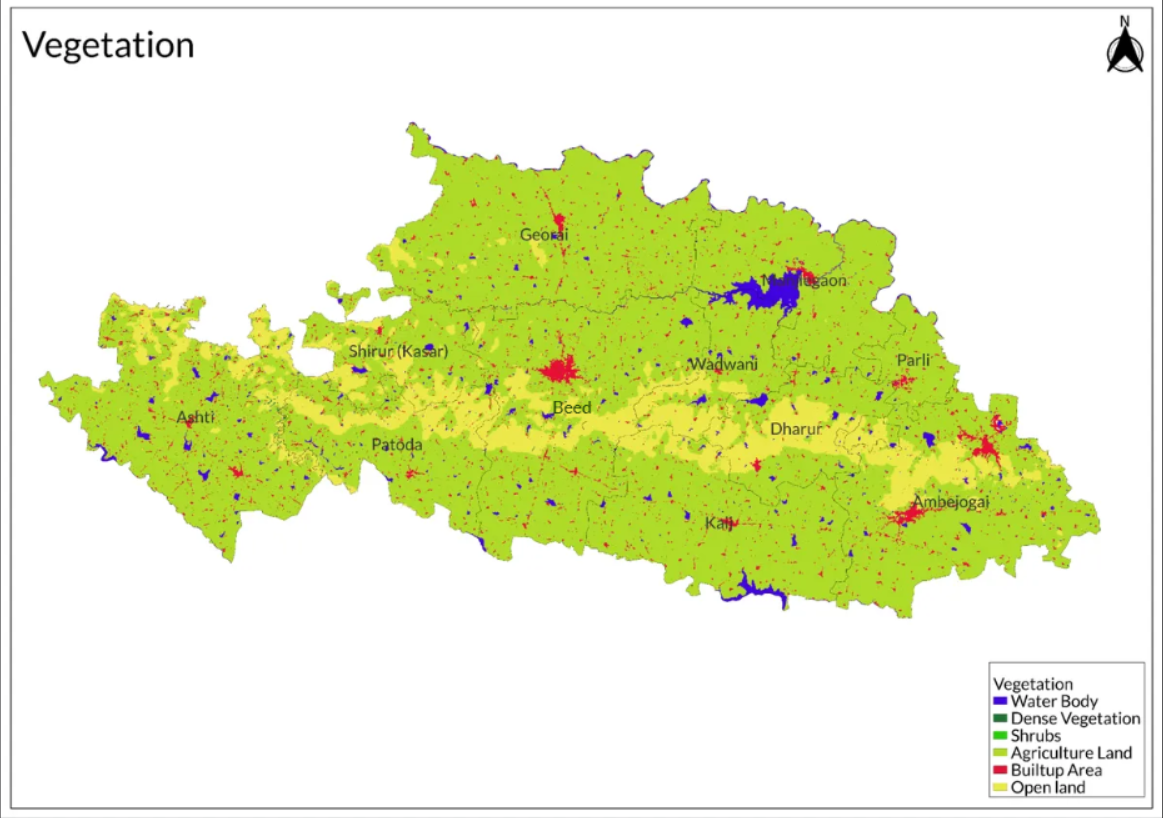

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Birds

- Land Use

- Forest Reserves

- Environmental Concerns

- Water Scarcity

- Climate Change Vulnerability

- Air Pollution

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Shramdaan Abhiyan

- Graphs

- Water

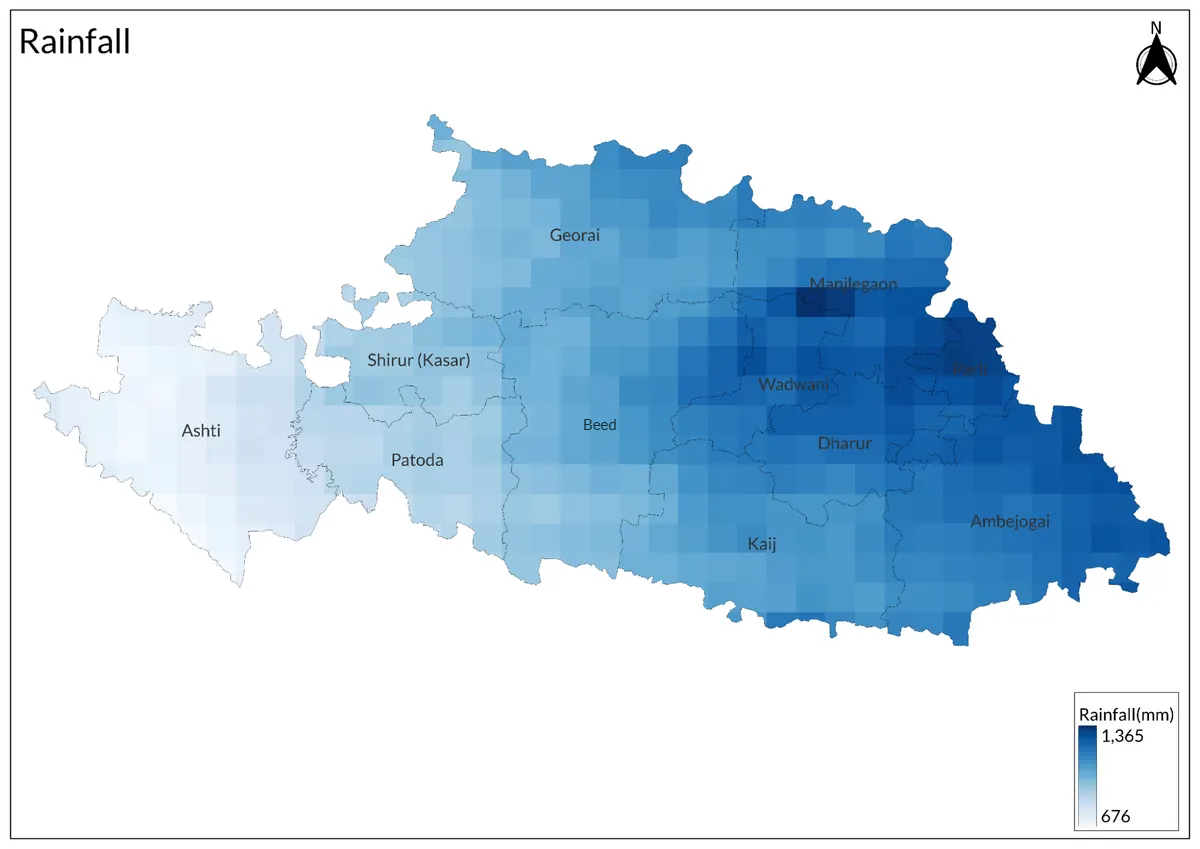

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Wildlife Projects (Area and Expenses)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

BEED

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Beed district, situated in the arid Marathwada region of Maharashtra, features a semi-arid climate and is prone to drought. Its landscape is defined by rugged terrain, limited forest cover, and dependence on seasonal rivers such as the Manjra.

Physical Features

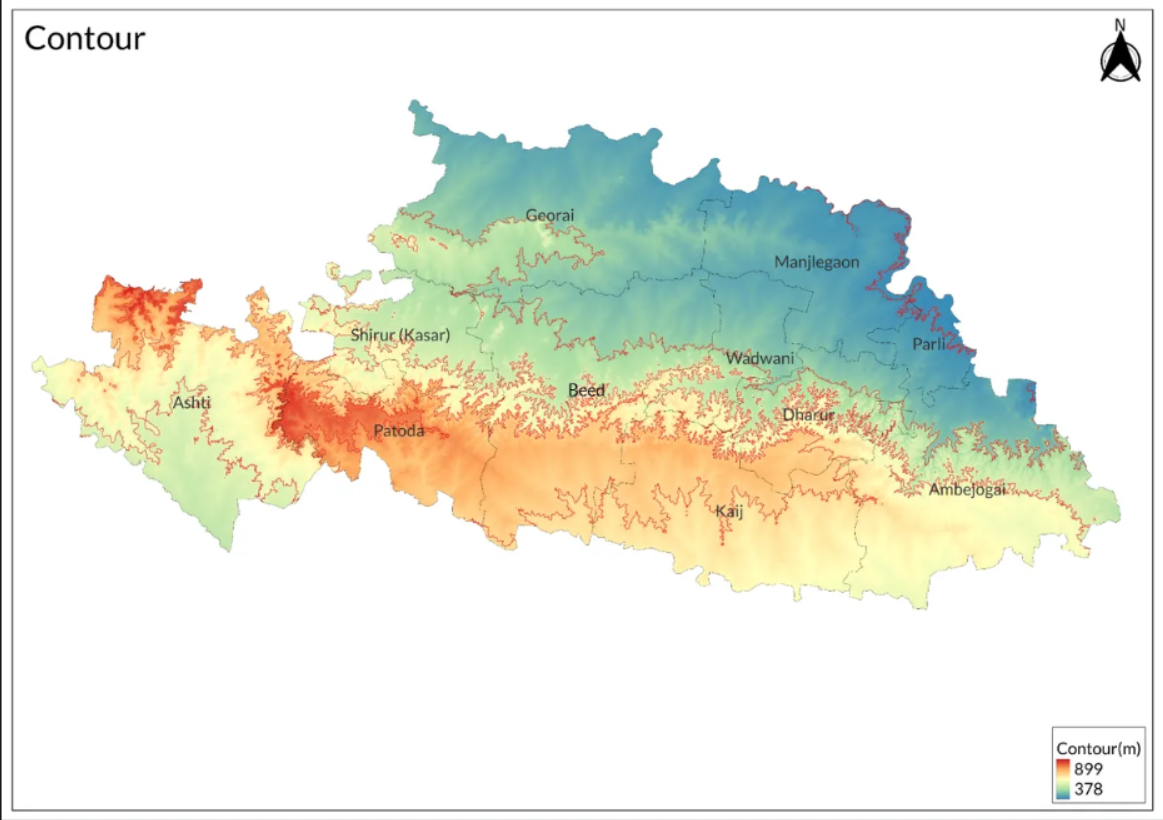

According to the District Gazetteer of 1969, Beed district is characterized by three distinct geographical regions: Lowland Bhir, Plateau Bhir, and the Sina Basin of Ashti tahsil.

The Lowland Bhir consists of the Godavari valley and the Gangathadi area, which features low-lying land approximately 5 to 10 kilometers wide. This region is known for its extremely fertile soils that support heavy crops such as jowar, cotton, and pulses, primarily relying on rainfall for irrigation. Villages in this area are often spaced about 1.5 kilometers apart and depend on the Godavari River for drinking water. Major villages include Chakalamba, Umapur, Dhondrai, Georai, Jategaon, and Manjlegaon. While irrigation is rare, the fertility of the soil allows for significant cultivation during the rabi season.

The Plateau Bhir rises steeply from Lowland Bhir and is characterized by dissected hills composed mainly of basaltic rocks. The soils here are thinner and more eroded compared to those in Lowland Bhir. Hardy crops such as bajri and jowar are cultivated during the kharif season, while rabi crops benefit from better groundwater conditions found in the valleys of streams draining southwards towards the Manjra River. Villages in this region are typically located along streams, with larger settlements at road crossings.

The Sina Basin encompasses most of the Ashti tehsil and features valleys of small tributary streams draining into the Sina River. This region has poorer soils due to its sloping terrain and lower average rainfall, which ranges from 509 mm to 638 mm. The prevalence of stony ground contributes to its designation as the poorest region in the district, leading to significant migration to irrigated areas in the nearby Ahmednagar district. Despite these challenges, this area has seen an increase in small irrigation projects, with jowar occupying a substantial portion of the cropped area.

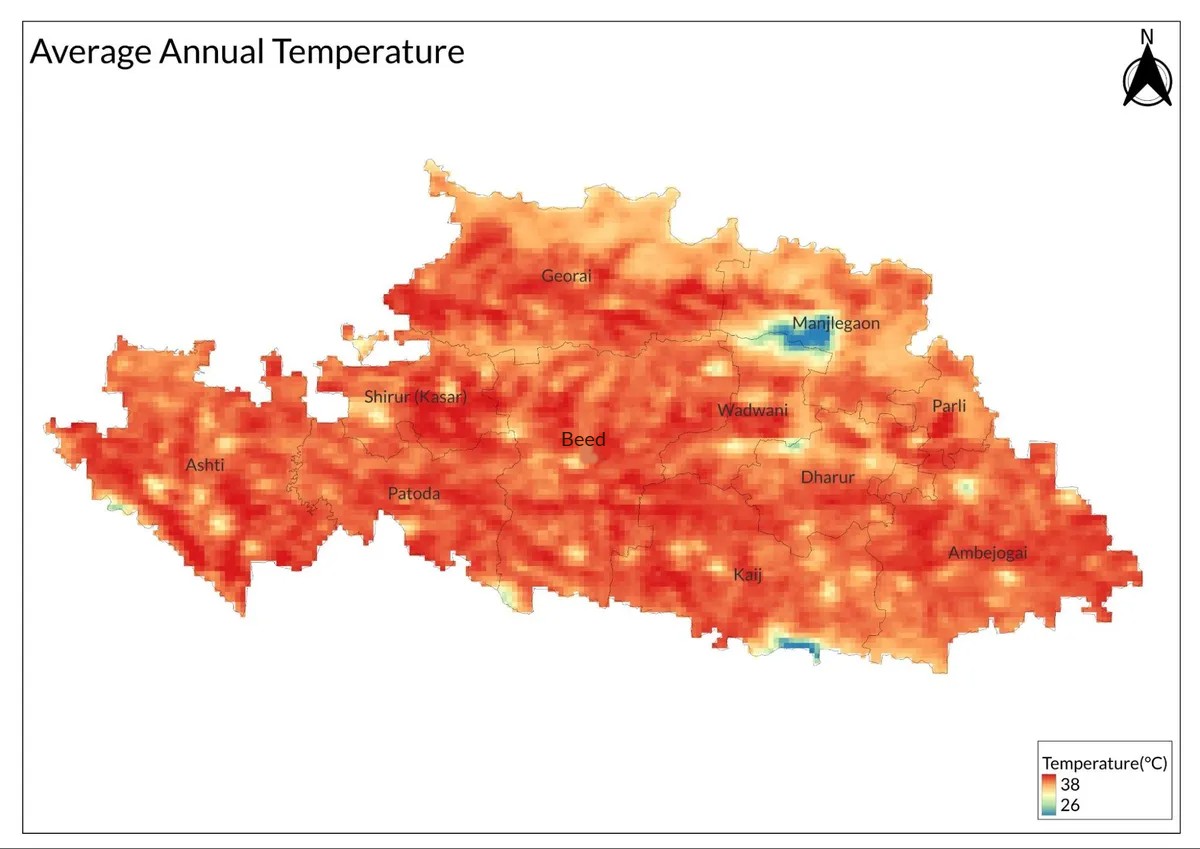

Climate

According to the Meteorological Department of the Government of India, Poona, the climate of Beed district is predominantly dry, except during the southwest monsoon season. The year is divided into four seasons: a cold season from December to February, a hot season from March to May, the southwest monsoon from June to September, and a post-monsoon period in October and November. The average annual rainfall for the district is 750.1 mm (29.53 inches), with rainfall increasing from west to east, ranging from 665.3 mm (26.19 inches) at Ashti near the western border to 850.6 mm (33.49 inches) at Mominabad near the eastern border. Approximately 80 percent of annual rainfall occurs during the southwest monsoon season, with September being the rainiest month.

Recent data indicate that climate patterns continue to show variability; for instance, rainfall records at Beed have extended over approximately 85 years, while those at other stations range from 8 to 17 years. On average, there are about 41 rainy days each year (defined as days with rainfall of 2.5 mm or more), although this number varies across different locations within the district.

Geology

The section on geology has been contributed by the Geological Survey of India, Calcutta. Beed district is divided into two main regions: the Balaghat or highlands, in the southern and eastern parts, and the Payinghat, or lowlands. A low spur of the Western Ghats runs from Ahmadnagar to Amba.

The district is underlain by Deccan traps of Cretaceous-Eocene age, consisting of 'Plateau Basalt' rocks that are uniform in composition, similar to dolerite or basalt, with an average specific gravity of 2.9. These rocks are dark grey or dark greenish-grey and can be classified into vesicular and non-vesicular types. Non-vesicular traps are hard and compact, while vesicular types are softer.

Under tropical conditions, the Deccan traps decompose to form laterite (of Pleistocene age), which caps the traps in some areas and can be rich in iron ore. Beds of gravel and clay from the upper Pliocene to Pleistocene age containing fossil bones of extinct mammals overlie the traps in the valleys of the Godavari and its tributaries.

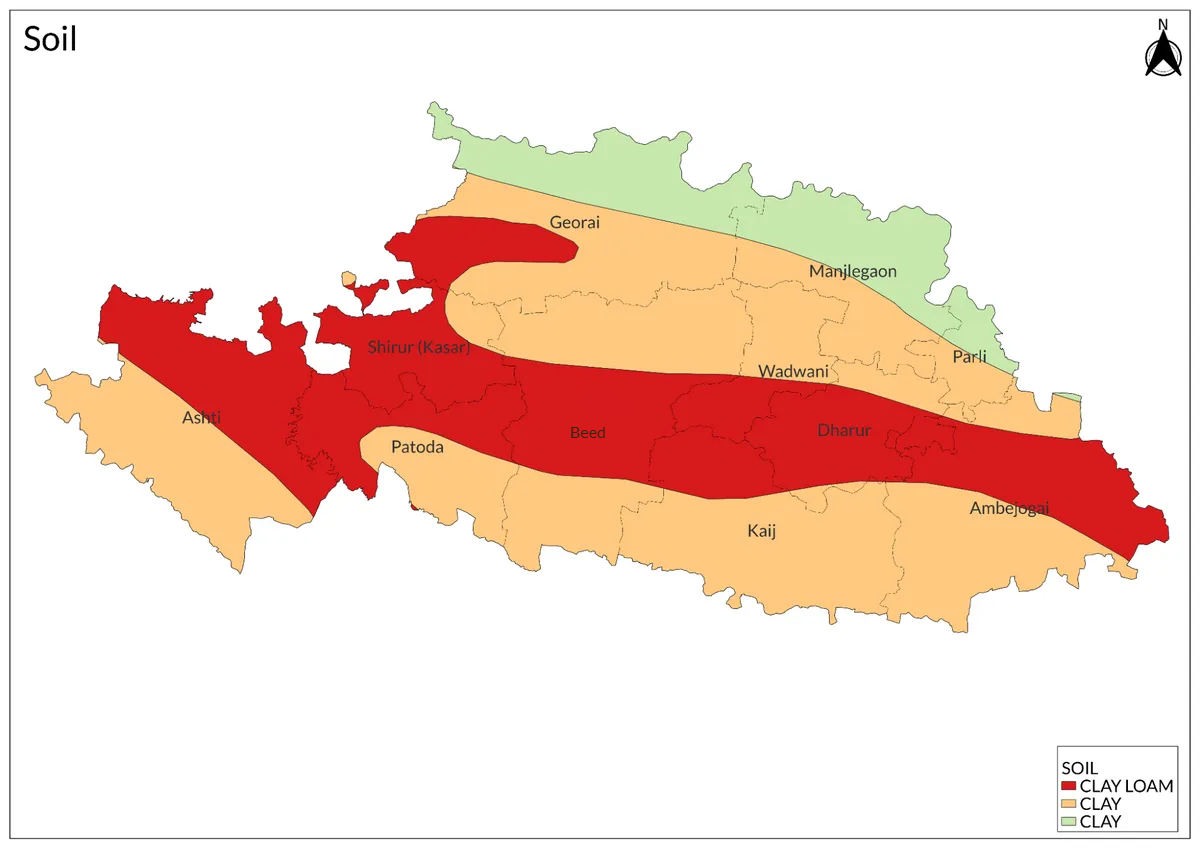

The traps weather into fertile black cotton soil, which is widespread in the district. Nodules of kankar are commonly found within this soil layer.

Soil

Soil types in the Beed district vary significantly across its regions. In Lowland Bhir, particularly along the Godavari valley, soils are deep and fertile, supporting heavy crops like jowar, cotton, and pulses. This region relies on rainfall for irrigation due to challenges in well sinking.

In Plateau Bhir, soils are thinner and more eroded. Hardy crops such as bajri and jowar are cultivated during the kharif season, while rabi crops benefit from better groundwater conditions found in valleys.

Minerals

No minerals of economic value are found in the district. The basalts, which are prevalent throughout, provide excellent and durable building stones, as well as materials for road metal and ballast. Kankar is typically found in stream courses and is locally burned for lime. Deposits of red lithomargic clays have been noted in the southern parts of the Ashti tahsil. The ferruginous type of laterite has historically served as a useful source of iron ore for smelting. Agate and chalcedony can be found in the geodes of the basalts, while sands suitable for plaster, mortar, and concrete can be obtained from the beds of the Godavari River and other streams.

Irrigation primarily comes from wells, where water levels can be variable. Although the yield is considerable, the groundwater reservoirs in the traps are small, and groundwater levels fluctuate over short distances. Traps with close horizontal joints yield more water, while those with columnar joints follow in importance. The presence of red boles in a well generally indicates a poor yield. Wide, shallow depressions bounded by trap ridges are ideal sites for wells.

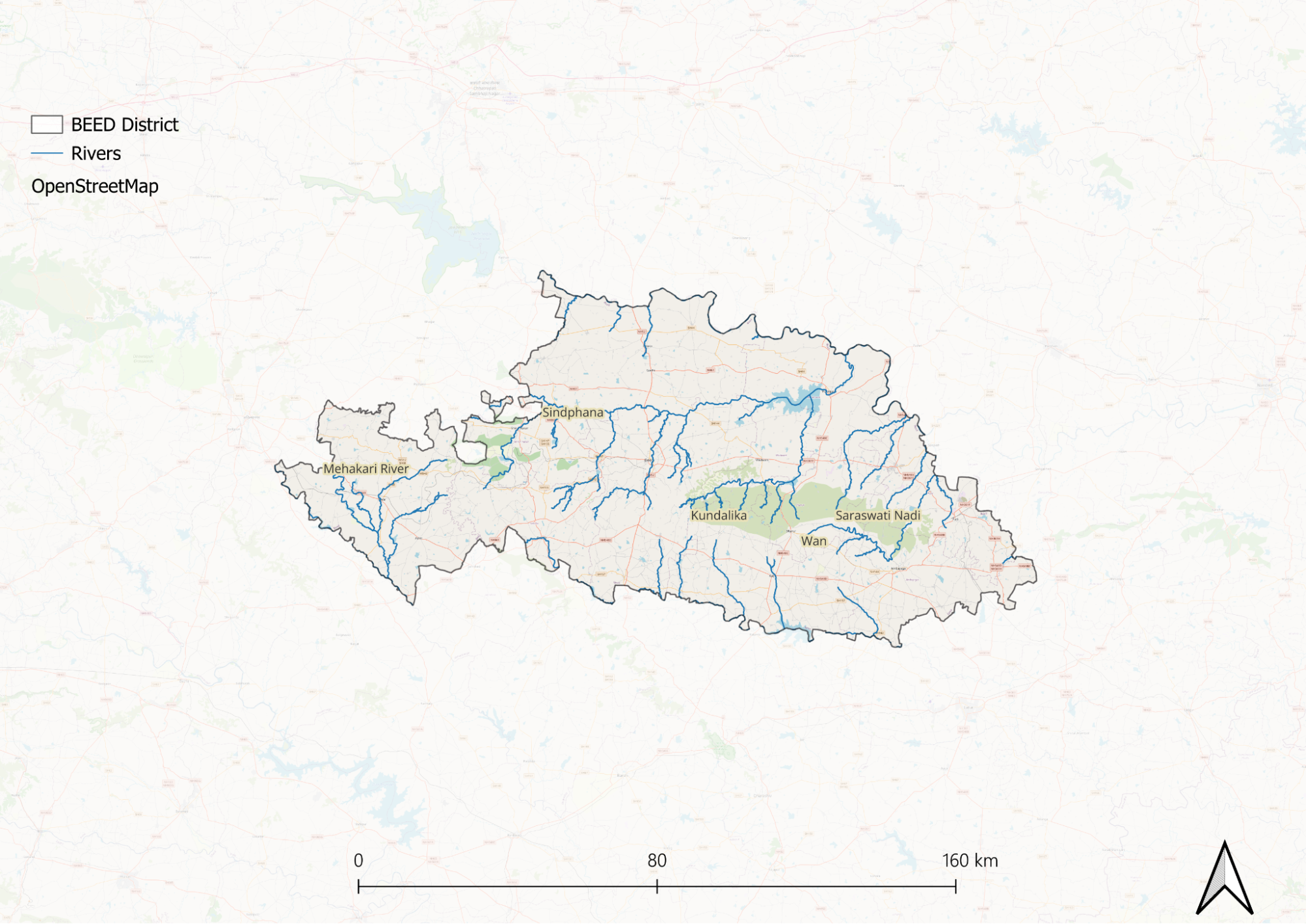

Rivers

The Beed district features several significant rivers that contribute to its geography and agriculture. The most prominent river is the Godavari, which flows through the district and serves as a crucial water source for irrigation and drinking water. The Godavari valley is characterized by fertile soils, allowing for the cultivation of crops like jowar, cotton, and pulses. Villages along the southern bank of the Godavari depend on the river for their water supply, with well sinking being challenging due to deep soils.

The Bendsura River is notable for its historical significance, as the town of Bhir developed along its banks. This river has shaped the local landscape and provided water resources for agriculture. Additionally, several small tributary streams drain into these major rivers, enhancing the irrigation potential of the Beed district. These streams are vital for supporting agriculture in regions where rainfall may be insufficient.

Botany

Beed district's forest produce is largely consumed locally, with a high demand for teak timber and firewood. However, local forests are insufficient to meet this demand, leading to imports from other districts. Consequently, many residents use mango, salai, and neem for construction, resulting in the clearing of these trees from fields. Minor forest products include fodder grasses, temru leaves for bidi production, sandalwood, charoli, and gums.

The district's roadside trees include karanj, neem, and various ficus species. Common field trees are mango, neem, tamarind, and jamun. Fiber plants such as kekti and hemp are also present. The region has a variety of water plants like lotuses and several weeds, including tarota and lantana. Exotic ornamental plants like the rain tree have been introduced into gardens and along avenues. The area supports diverse vegetables, including beans, cabbage, carrots, and tomatoes.

Wild Animals

The wildlife in the Beed district has significantly declined due to deforestation and poaching. Once home to many tigers, the species is now practically extinct, with only a few panthers remaining in sheltered areas. These panthers often venture into agricultural lands in search of food. The district is home to small populations of chital and chinkara, as well as more common species like wild boar and jackals, which cause damage to crops. Monkeys, particularly langurs, are prevalent and can damage gardens. Other common animals include squirrels and hares, while various rodents and bats contribute to the ecosystem by controlling insect populations.

The district's terrain includes hills with sparse forests, particularly around Ambejogai and Manjarsumbha, where snakes such as pythons and shield-tailed snakes may be found. Non-poisonous snakes like blind snakes and sand boas inhabit the area, while more dangerous species include cobras and kraits. The diverse snake population plays a role in controlling pests but can pose risks to humans. The region also features a variety of vegetation, including grasses, shrubs, and trees that support local wildlife.

Birds

Owing to the poverty of habitat reflected in the open stocking of the forest and general scarcity of water, the bird population is also meager. Even the most common game birds, like peafowl and grey jungle fowl, are rarely encountered.

Land Use

Forest Reserves

Environmental Concerns

Water Scarcity

Water scarcity in Beed district, Maharashtra, has become a pressing issue due to a combination of drought conditions and insufficient rainfall. The district has experienced several drought events over the years, notably in 1985–86, 1987–88, 1992–93, 2001–02, 2005–06, and 2011–12. Beed is situated in the Western Maharashtra Dry or Scarcity Zone, where it receives very little rainfall, exacerbating the water crisis.

Rising temperatures have further contributed to the drying up of water sources, leading to significant shortages. Villagers have been forced to walk long distances to fetch water, often travelling up to 18-20 kilometers. In many cases, the water they receive from private tankers is contaminated and unfit for drinking, raising health concerns among residents.

The dire situation has compelled many villagers to migrate to urban areas such as Pune, Satara, Sangli, and Kolhapur in search of better water access. The ongoing water scarcity has not only affected daily life but has also had severe socio-economic impacts, including low agricultural yields and increased rates of seasonal migration.

The groundwater levels in Beed have dropped dramatically over the years. Reports indicate that the water table has declined significantly since 2008, with bore wells needing to be dug deeper to access water. In some instances, villagers have had to drill wells over 300 meters deep to find sufficient water supplies.

Efforts to address these challenges have included initiatives focused on rainwater harvesting and community engagement. Organizations like Yuva Gram have been working since 1984 to revitalize water resources and empower local communities to manage their water needs sustainably. However, despite these efforts, the region continues to face acute water shortages that threaten livelihoods and community stability.

Climate Change Vulnerability

The Beed district in Maharashtra, India, is significantly vulnerable to climate change, particularly due to its susceptibility to drought. Located in the Marathwada region, Beed is recognized as a drought-prone area, facing severe challenges related to water scarcity.

The impacts of climate change have led to livelihood insecurity for many residents, limiting their access to better opportunities and resources. The district exhibits low adaptive capacity to climate change, making it difficult for communities to cope with the increasing frequency and severity of droughts.

One of the most alarming consequences of this vulnerability is the health crisis faced by women in Beed. Many have been compelled to undergo hysterectomies as a means to avoid missing work and losing pay due to debilitating menstrual symptoms exacerbated by the demanding labor conditions in agriculture. This situation highlights the intersection of climate change and health issues, further complicating the socio-economic landscape in the district.

Air Pollution

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Shramdaan Abhiyan

Deficient rainfall significantly impacted water conservation efforts in Beed district, Maharashtra, leaving farmers facing potential crop losses. In April and May 2018, locals from 15 villages participated in a 45-day "Shramdaan Abhiyan," a voluntary labor campaign aimed at building rainwater harvesting infrastructure. This initiative was launched by the Global Vikas Trust, led by social activist Mayank Gandhi, who had adopted these villages for water conservation.

During the campaign, residents dug trenches, constructed farm ponds, and constructed watershed structures and check dams to enhance rainwater preservation. They managed to create over 80 crore liters of surface water storage and 1,600 crore liters of underground storage capacity. However, the lack of adequate rainfall rendered these efforts largely ineffective. Gandhi noted that the region received only 41% of its average rainfall for the season, with June recording just 71.6 mm compared to an average of 136.7 mm, and July seeing only 60 mm against an average of 183.7 mm.

Farmers expressed their frustration over the situation. Anant Rupnar from Parchundi village lamented that despite their hard work, the anticipated rains had not materialised, leading to drying soybean crops and damage to cotton crops from pests. Mukteshwar Kadbhane from Bhilegaon village warned that without significant rainfall in the following days, their cotton crops would face near-total destruction.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Deccan Herald. 2022. Climate Crisis in Maharashtra's Beed Forces Women to Choose Between Womb and Work. Deccan Herald, Maharashtra.https://www.deccanherald.com/india/maharasht…

Himanshu Nitnaware. 2024. Vanishing Wells of Marathwada: Farmers Report Water Table Dropped to 300 Metres in 30 Years.Down to Earth, April 10.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/water/vanishi…

Press Trust of India. 2018. Scarce Rainfall Hits Water Conservation Project in Maharashtra's Beed. NDTV, All India, August 04.https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/scarce-rainf…

S. 2022.Drought Identification and Analysis of Precipitation Trends in Beed District, Maharashtra. Materials Today: Proceedings, Volume 61, Part 2, Pages 332-341.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Shrinivas Deshpande. 2019. No Bathing, Washing in Drought-Hit Beed. Hindustan Times, Pune, May 31.https://www.hindustantimes.com/pune-news/no-…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.