Contents

- Healthcare Infrastructure

- Medical Education & Research

- Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College

- Public Health Challenges Through Time

- COVID Stories

- The Case of Primary Healthcare Centres in Villages

- Administrative Response

- Graphs

- Healthcare Facilities and Services

- A. Public and Govt-Aided Medical Facilities

- B. Private Healthcare Facilities

- C. Approved vs Working Anganwadi

- D. Anganwadi Building Types

- E. Anganwadi Workers

- F. Patients in In-Patients Department

- G. Patients in Outpatients Department

- H. Outpatient-to-Inpatient Ratio

- I. Patients Treated in Public Facilities

- J. Operations Conducted

- K. Hysterectomies Performed

- L. Share of Households with Access to Health Amenities

- Morbidity and Mortality

- A. Reported Deaths

- B. Cause of Death

- C. Reported Child and Infant Deaths

- D. Reported Infant Deaths

- E. Select Causes of Infant Death

- F. Number of Children Diseased

- G. Population with High Blood Sugar

- H. Population with Very High Blood Sugar

- I. Population with Mildly Elevated Blood Pressure

- J. Population with Moderately or Severely High Hypertension

- K. Women Examined for Cancer

- L. Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption

- Maternal and Newborn Health

- A. Reported Deliveries

- B. Institutional Births: Public vs Private

- C. Home Births: Skilled vs Non-Skilled Attendants

- D. Live Birth Rate

- E. Still Birth Rate

- F. Maternal Deaths

- G. Registered Births

- H. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- I. Institutional Deliveries through C-Section

- J. Deliveries through C-Section: Public vs Private Facilities

- K. Reported Abortions

- L. Medical Terminations of Pregnancy: Public vs Private

- M. MTPs in Public Institutions before and after 12 Weeks

- N. Average Out of Pocket Expenditure per Delivery in Public Health Facilities

- O. Registrations for Antenatal Care

- P. Antenatal Care Registrations Done in First Trimester

- Q. Iron Folic Acid Consumption Among Pregnant Women

- R. Access to Postnatal Care from Health Personnel Within 2 Days of Delivery

- S. Children Breastfed within One Hour of Birth

- T. Children (6-23 months) Receiving an Adequate Diet

- U. Sex Ratio at Birth

- V. Births Registered with Civil Authority

- W. Institutional Deliveries through C-section

- X. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- Family Planning

- A. Population Using Family Planning Methods

- B. Usage Rate of Select Family Planning Methods

- C. Sterilizations Conducted (Public vs Private Facilities)

- D. Vasectomies

- E. Tubectomies

- F. Contraceptives Distributed

- G. IUD Insertions: Public vs Private

- H. Female Sterilization Rate

- I. Women’s Unmet Need for Family Planning

- J. Fertile Couples in Family Welfare Programs

- K. Family Welfare Centers

- L. Progress of Family Welfare Programs

- Immunization

- A. Vaccinations under the Maternal and Childcare Program

- B. Infants Given the Oral Polio Vaccine

- C. Infants Given the Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) Vaccine

- D. Infants Given Hepatitis Vaccine (Birth Dose)

- E. Infants Given the Pentavalent Vaccines

- F. Infants Given the Measles or Measles Rubella Vaccines

- G. Infants Given the Rotavirus Vaccines

- H. Fully Immunized Children

- I. Adverse Effects of Immunization

- J. Percentage of Children Fully Immunized

- K. Vaccination Rate (Children Aged 12 to 23 months)

- L. Children Primarily Vaccinated in (Public vs Private Health Facilities)

- Nutrition

- A. Children with Nutritional Deficits or Excess

- B. Population Overweight or Obese

- C. Population with Low BMI

- D. Prevalence of Anaemia

- E. Moderately Anaemic Women

- F. Women with Severe Anaemia being Treated at an Institution

- G. Malnourishment Among Infants in Anganwadis

- Sources

BEED

Health

Last updated on 3 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Beed’s healthcare landscape, like many other regions across India, is shaped by a mix of indigenous and Western medical practices. For centuries, indigenous knowledge and treatments provided by practitioners such as hakims and vaidyas have formed the foundation of healthcare in the region. This long-standing relationship between communities and their natural environment played a key role in shaping the district’s early medical traditions. Over time, its landscape has gradually evolved with the introduction and expansion of more specialized medical services.

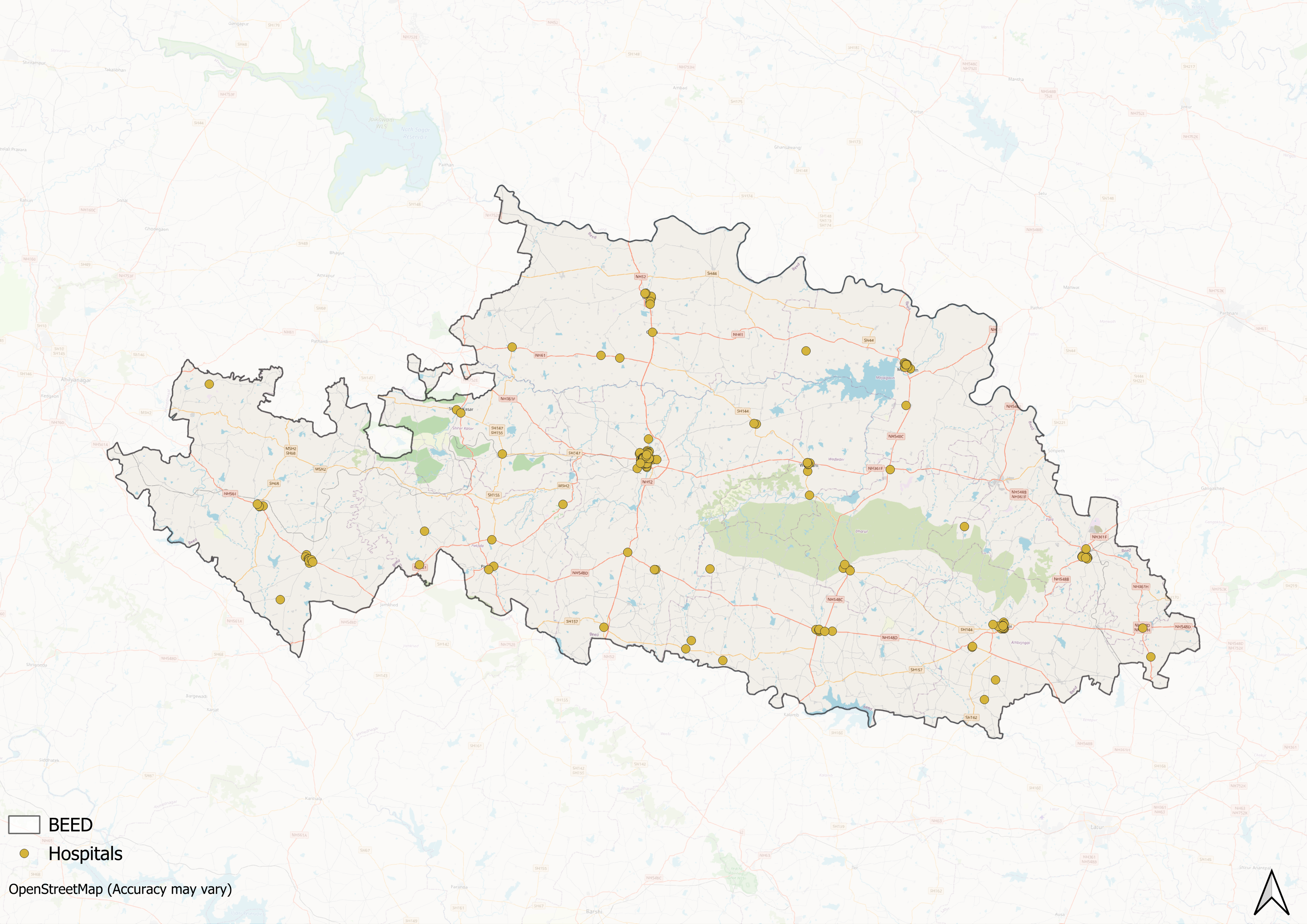

Healthcare Infrastructure

Similar to other regions in India, Beed’s healthcare infrastructure follows a multi-tiered system that involves both public and private sectors. The public healthcare system is structured into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. Primary care is provided through sub-centers and primary health centers (PHCs), secondary care is managed by community health centers (CHCs) and sub-district hospitals, while tertiary care, the highest level, is delivered through medical colleges and district hospitals.

Supporting this structure is a network of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) who, as described by the National Health Mission, serve as “an interface between the community and the public health system.” Over time, this multi-layered healthcare model has been continuously shaped and refined by national healthcare policies and reforms to improve universal health coverage across regions.

Beed’s formal healthcare infrastructure, like much of India, has its origins in the colonial era, which laid the groundwork for the system in place today. According to the district Gazetteer (1969), Beed experienced a notable increase in the number of hospitals and dispensaries between 1911 and 1941. However, it was after Independence that notable improvements in accessibility and infrastructure began to take shape. By the 1960s, the district had two hospitals, along with several civil, ayurvedic, and unani dispensaries, and PHCs.

In the post-liberalization period, particularly in the 21st century, the expansion of private healthcare facilities became increasingly visible. Many of these hospitals and clinics were established by local trusts, non-governmental organizations, and private practitioners.

However, similar to broader patterns that can be seen across India, the district’s healthcare infrastructure has developed unevenly across geographic lines.

Medical Education & Research

Medical education and research form an important part of Beeds’s healthcare system. As noted by Mathew George (2023), medical institutions in India generally serve a “dual purpose” by training healthcare professionals and providing services to the local population. Notably, here, both public and private institutions contribute to this sector.

Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College

Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College (SRTR GMC) is a government medical college located in Ambajogai, Beed district. Notably, it is known as Asia’s first rural medical college. The institution is affiliated with the Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, Nashik. The college was founded under the leadership of Dr. V.K. Dawale, who served as its first dean.

![Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College, Beed district[1]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/beed/health/swami-ramanand-teerth-rural-government-medical-_tIXvNhW.png)

The college offers postgraduate degrees and diploma courses in medicine. Some specializations offered are Anatomy, Biochemistry, Physiology, Microbiology, Pathology, Pharmacology, Community Medicine, Anesthesiology, General Medicine, Paediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ENT, General Surgery, Ophthalmology, and related clinical disciplines.

Public Health Challenges Through Time

Historically, the Beed district has struggled with a range of communicable diseases. The District Gazetteer (1969) reports recurring outbreaks of malaria, tuberculosis, cholera, smallpox, guinea worm disease, and leprosy. In response, the Medical and Public Health Department introduced a number of preventive and curative initiatives. These included vaccination drives, sanitation campaigns, and disease eradication programs, which laid the foundation for later public health interventions.

COVID Stories

The Case of Primary Healthcare Centres in Villages

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed both the deficiencies in the district's primary healthcare systems and the remarkable bravery of some individuals during this crisis. Several primary health sub-centers, including the one at Pahadi-Paragon, were reported to be chronically understaffed and, in some cases, remained non-functional for extended periods. As a result, many villages lacked timely access to essential medical care during the pandemic. These deficiencies underscored longstanding issues within the district’s healthcare delivery system, especially the uneven distribution of medical personnel and resources.

Administrative Response

During the pandemic, local administrative efforts played a notable role in managing the crisis. The Beed Police, under the leadership of IPS Harssh Poddar, implemented a decentralized response strategy aimed at prevention and community engagement. This included the establishment of Help Cells and the formation of village-level intelligence committees to monitor population movement and prevent the entry of unscreened individuals into rural areas. These measures were credited with raising awareness, encouraging public compliance with health protocols, and strengthening localized pandemic response efforts across the district.

Graphs

Healthcare Facilities and Services

Morbidity and Mortality

Maternal and Newborn Health

Family Planning

Immunization

Nutrition

Sources

Bureaucrats India. 2020. "Handling the Covid Crisis: Beed Police Shows the Way." Bureaucrats India.https://bureaucratsindia.in/news/good-govern…

Diksha Munjal, Prateek Goyal, and Tanishka Sodhi. 2021. "Shambolic Rural Health System Piles on Covid Misery in Beed." Newslaundry.https://www.newslaundry.com/2021/06/24/shamb…

M Choksi, B. Patil et al. 2016. Health systems in India.Vol 36 (Suppl 3). Journal of Perinatology.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC514…

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1969. Bhir District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationery & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

National Health Mission (NHM). "About Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA)." National Health Mission, India.https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1…

Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College. Home.https://www.srtrmca.org/

Tanvi Patil. 2020. 2 Months & 0 Active Cases: How Beed Police Kept the District Safe from COVID-19. The Better India.https://thebetterindia.com/225568/maharashtr…

Last updated on 3 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.