Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

- Dhawara

- Types of Farming

- Bajri (Small Millet) Farming

- Suranji (Chay Root)

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Celestial Influence on Farming

- Intimate Connection with Village Life

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Graphs

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Agricultural Lending

- B. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

CHH. SAMBHAJI NAGAR

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

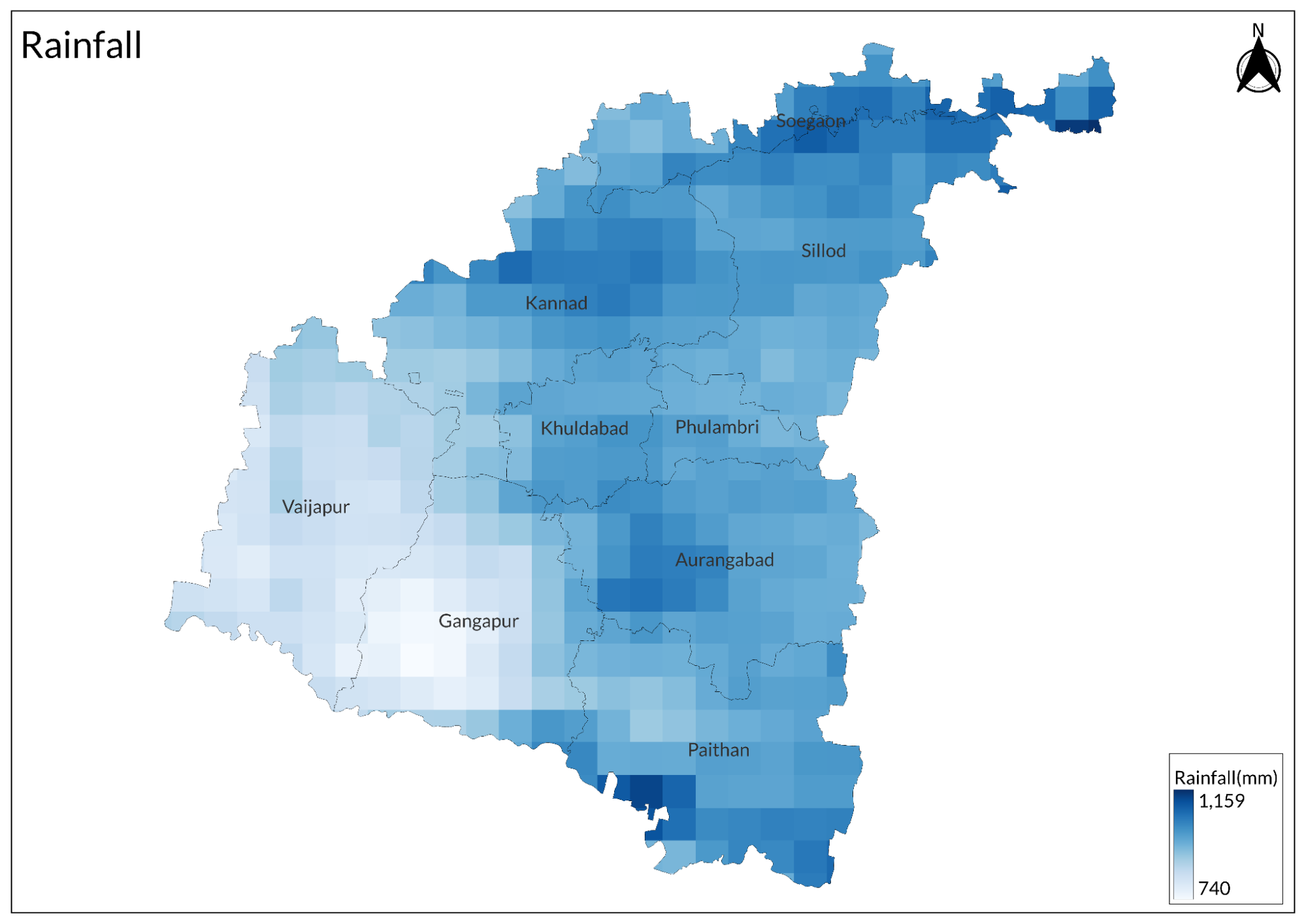

Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar is located in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra. According to the NABARD Credit Plan (2023-24), “Out of 10.07 lakh hectares of the total area, 8.14 lakh hectares are cultivable.” The district has a slim disparity between its rural and urban populations. Agriculture plays a pivotal role in the district's economy, and a large proportion of the rural population relies on farming as their primary livelihood.

Crop Cultivation

Historically, farming in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar was closely tied to the seasonal rainfall and temperature fluctuations that defined the region’s climate. The Kharif (monsoon) and Rabi (post-monsoon) cropping systems, adapted to the seasonal changes, have been vital to the area's agricultural cycle.

It is described in the colonial district Gazetteer (1884) that during the Kharif season, crops such as Bajri (pearl millet), Kapas (cotton), and Tur (pigeon pea) were commonly grown, while Nilwa Jowar (sorghum) and pulses like Mung (green gram) and Urad (black gram) were also cultivated. The Rabi season, which occurs during the winter months, saw the cultivation of Jowar (sorghum), Gehun (wheat), and Chana (chickpea). However, one of the more fascinating aspects noted in the Gazetteer is that the practice of utilising Bagat (garden) lands, which are small, specialised plots, was widespread for cultivating high-value crops. These lands were used to grow crops like Ganna (sugarcane), Rajgira (amaranth), and Poppy, the latter of which was notably discontinued in the late 19th century.

Today, according to the NABARD District Credit Plan for 2023–24, major crops sown in the district include cotton (cultivated on approximately 4.07 lakh hectares), maize (1.77 lakh hectares), and soybean (0.12 lakh hectares). These form the core of the district’s agricultural output.

Horticulture has also expanded, aided by the district's climatic suitability. Pomegranate, sweet lime, and Kesar mango are also important cash crops. Notably, the Kesar mango grown in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar has received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag.

Agricultural Communities

In Sambhaji Nagar, farming is carried out by both small, marginal farmers and large farmers. According to the NABARD report (2023-24), 83.09% of landholders in the district are small farmers, owning less than 2 hectares of land, and they control only 56.39% of the total agricultural land. This highlights the presence of both small and large farmers in the region. The colonial district Gazetteer (1884) also records communities that Kunbis have long been associated with farming in the area.

Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

Dhawara

Shahu Patole, in his book, The Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada (2024), talks about a festival known as Dhawara. Dhawara is a cherished tradition in the local farming culture, marking the celebration of a successful harvest with a sacred meal. The preparations for Dhawara begin on the new moon of Diwali, a day dedicated to worshiping the Pandavas, the five legendary brothers from the Mahabharata. In the fields, five small stones are selected and painted with Chuna (limewash), showing the Pandavas.

As part of the ritual, wheat flour dough is shaped into various forms, such as plain balls, fruits, and lamps, before being steamed. These, along with dried dates, dry coconut, Ambil (a tangy buttermilk preparation infused with chilies and coriander), Kadhi (a tempered chickpea-buttermilk curry), and Wadya (steamed gram flour cakes), are offered as Naivedya (a devotional offering). A Morva (medium-sized earthen pot) and Shendur (a sacred red powder) are also placed near the symbolic Pandavas.

In keeping with tradition, five stacks of Jowar Pachundas (bundles of harvested sorghum) are arranged upright before the stones. A lamp is then placed inside the Morva and lit as a mark of reverence. At dusk, the Morva is carefully buried near the painted stones, symbolizing the completion of the Dhawara ritual and expressing gratitude for the harvest.

Types of Farming

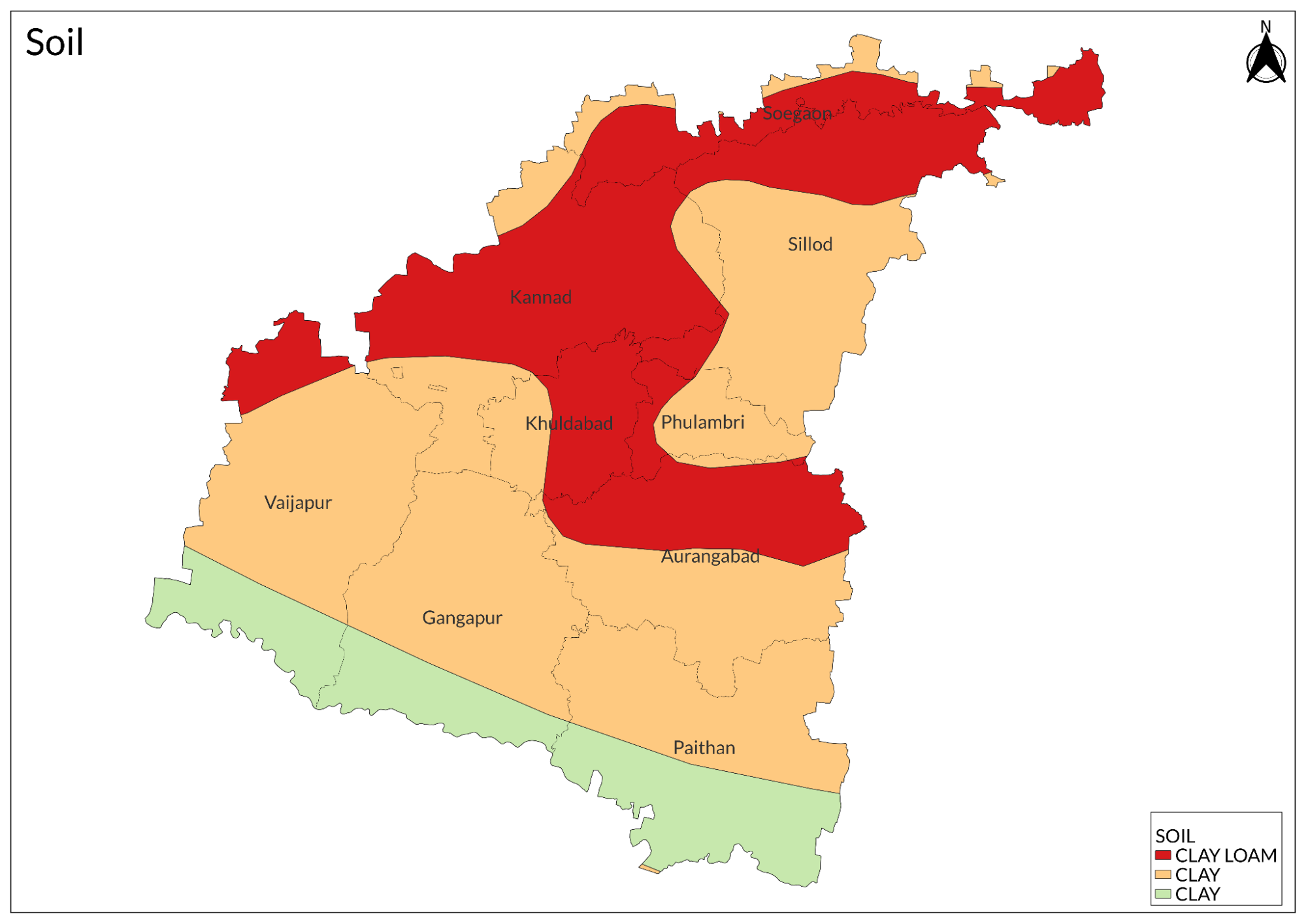

Farming in Sambhaji Nagar is strongly influenced by the region’s diverse soil types and topographical features, which determine the crops that can be cultivated and the farming practices used. According to the Gazetteer (1884), the soils in the district include black (regar), red (masab), and a mixture of both (milwa). Local farming communities, particularly the Kunbis, as mentioned in the gazetteer, have a rich vocabulary for describing these soils: "kala mitti" for black soil, "pandri mitti" for white soil found around villages, "chun khada" for calcareous soil, "matwant thandi" for red soil, and "balda" for stony soil. These soil types play a crucial role in determining the suitability of crops, and the farming methods are tailored accordingly.

Bajri (Small Millet) Farming

Among the most important crops historically grown in Sambhaji Nagar is Bajri (small millet). The Gazetteer highlights the fact that Bajri thrives in poorer soils, often found in areas with "barad," "chikni," and "pandri" soil types. These are soils that require intensive and annual ploughing.

The sowing season for Bajri typically begins in the early monsoon months of July and August, when the land is carefully prepared by ploughing and cross-ploughing. Farmers use a combination of tools, such as the mogra for harrowing and the vakhar for further soil work. These traditional techniques are labor-intensive but vital for the crop’s success. After sowing, farmers use a "rahak" to cover the seeds with earth and level the field.

Once the crop starts to grow, Bajri needs little more than occasional weeding and protection from pests like the "khurpud" insect. The grain matures in about three months, typically around November or December, when it is time for harvest. During harvest, the stalks are cut, and the grain is separated using a traditional threshing technique: cattle trample the stalks to extract the grain, which is then winnowed by hand. Bajri, being a staple crop, serves as the main food source for local families, ground into flour to make bread. The plant is versatile; its stalks are used for cattle fodder, and the cobs are burned as fuel.

Suranji (Chay Root)

While Bajri has long been a food staple in Sambhaji Nagar, another fascinating crop with a rich cultural and economic history is Suranji, also known as chaya root. Suranji is cultivated primarily for its red dye, which was once used in place of madder dye. According to the Gazetteer (1884), this crop thrives in the fertile black soils of the region, specifically, the "kali" and "morvandi" soils, which are ideal for its growth.

The cultivation process for Suranji is very complex and labor-intensive. In the past, farmers began preparing the land in November and December (Kartik and Margasir), ploughing it thoroughly before exposing it to the elements for two months. This exposure to the open air allowed the soil to take on the necessary qualities before being cross-ploughed in the spring months of March and April. After the first rains of the season, the soil was levelled using a vakhar, a large plough drawn by bullocks.

The actual planting of Suranji took place in June, with a small amount of seed, about half a seer to one seer per acre. Once planted, the crops needed careful attention, with multiple rounds of weeding. The plants grew slowly, taking about three years to reach maturity. At the end of this period, laborers would dig up the roots, which had become deeply set in the soil. The roots were then carefully sorted: thinner roots were more valuable because they produced a higher-quality dye. These roots were cut into 2-inch pieces and sold in the markets, often travelling as far as Bombay, where they were used for dyeing textiles.

The dyeing properties of Suranji were highly prized, and its cultivation brought economic benefits to the region, as well as a sense of cultural heritage tied to the craft of dyeing.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Celestial Influence on Farming

Agriculture has long been closely linked to the rhythms of nature, with farming cycles traditionally shaped by the changing seasons and various natural forces. While these cycles are primarily marked by the seasons today, farming practices in many regions were historically influenced by a variety of additional factors. In Sambhaji Nagar, the Gazetteer (1884) makes mention of a fascinating practice where farmers once aligned their agricultural activities with celestial movements.

At the heart of this practice were the nakshatras, the twenty-seven lunar divisions that marked different phases of the farming cycle. It is noted here that “the nakshatras are precisely calculated by Brahman astrologers, who regularly update the community on the movements of celestial bodies. Farming activities are undertaken only during the prescribed nakshatras, which… vary in length.”

This system illustrates a time when agriculture was intricately intertwined with astrology, showcasing how multiple factors, including celestial movements, played a significant role in determining farming cycles across the region.

Intimate Connection with Village Life

Farming in the past was also closely connected to village life. The gazetteer describes how village farming activities were communal and involved shared spaces. One such practice was the use of the kulla, a threshing floor located outside the village. This enclosed area was where grain was brought directly from the fields to be threshed.

Once harvested, the grain was carefully stored to ensure its preservation. It is noted in the Gazetteer (1884) that grain was often stored in kangis, wicker baskets placed outside homes. These baskets could hold between 5 and 15 maunds of grain and were about six ft. in height. To protect the grain from insects, the bottom and sides of the baskets were coated with cow dung, while the top was covered with a chapar to protect the grain from the elements.

In addition to the kangis, grain was sometimes stored for longer periods in underground vaults, known as pandri-mitti, made in the soft, muram earth where villages were built. These vaults were larger, holding between 120 and 225 maunds of grain, and provided an effective means of long-term storage.

Market Structure: APMCs

The Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) were established to ensure that farmers receive fair prices for their produce. These markets are structured to provide an organized environment where farmers can sell their crops to traders, who then bid on the commodities. Once the goods are sold, they are distributed to other regions to ensure wider availability.

In Sambhaji Nagar, according to the Agriculture Marketing Board, some of the common commodities sold in the APMCs include bulrush millet, husked wheat, sorghum (jowar), maize, and pigeon pea. Additionally, markets like Fulmbri are known for trading crops such as cotton and green gram.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

|

1 |

Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar |

1934 |

Radhakishan Devrao Pathade |

|

2 |

Pempriraja |

1981 |

Radhakishan Devrao Pathade |

|

3 |

Fulmbri |

2002 |

Anuradha Atul Chavan |

|

4 |

Nidhona |

2008 |

Anuradha Atul Chavan |

|

5 |

Gangapur |

1969 |

Bhausaheb Jayram Padar |

|

6 |

Turkabad (Kharadi) |

1989 |

Bhausaheb Jayram Padar |

|

7 |

Waluj |

1986 |

Bhausaheb Jayram Padar |

|

8 |

Kannad |

1963 |

Manoj Maharu Rathod |

|

9 |

Chincholi (Limbaji) |

1986 |

Manoj Maharu Rathod |

|

10 |

Chapaner |

1988 |

Manoj Maharu Rathod |

|

11 |

Devgaon (Rangari) |

2008 |

Manoj Maharu Rathod |

|

12 |

Khultabad |

2002 |

Sushma N Sabale |

|

13 |

Lasur Station |

1947 |

Sheshrao Bhavrao Jadhav |

|

14 |

Paithan |

1960 |

Raju Nana Asaram Bhumare |

|

15 |

Vihamandhwa |

1972 |

Raju Nana Asaram Bhumare |

|

16 |

Bidkin |

1980 |

Raju Nana Asaram Bhumare |

|

17 |

Pachod |

1981 |

Raju Nana Asaram Bhumare |

|

18 |

Sillod |

1968 |

Keshavrao Yadavrao Tayde |

|

19 |

Bharadi |

1979 |

Keshavrao Yadavrao Tayde |

|

20 |

Ajantha |

1979 |

Keshavrao Yadavrao Tayde |

|

21 |

Ambhai |

1988 |

Keshavrao Yadavrao Tayde |

|

22 |

Andhari |

1985 |

Keshavrao Yadavrao Tayde |

|

23 |

Soygaon |

1974 |

NA |

|

24 |

Vaijapur |

1947 |

Bhaginath (dada) Shahadrav Magar |

|

25 |

Shiur |

1981 |

Bhaginath (dada) Shahadrav Magar |

Graphs

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Gazetteers of the Nizam’s Dominion 1884 (reprinted 2006). Aurangabad District. Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Aurangabad. "District Profile." Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Aurangabad.

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan: Aurangabad. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

Shahu Patole. 2024. Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada, Anna he apoorna Brahman. Harper Collins.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.