Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

DHULE

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Dhule is a district renowned for its milk and ghee production and plays a vital role in Maharashtra’s agro-industrial economy. Agriculture, complemented by dairy farming and livestock rearing, particularly sheep and goats, forms the foundation of the district’s economic activities. The region’s agricultural lands, nestled in the foothills of the Satpura and Satmala mountain ranges, are framed by the Tapi River to the west, which divides Dhule into two parts, and the Narmada River to the north. While this unique topography provides fertile land, it also presents challenges for farming.

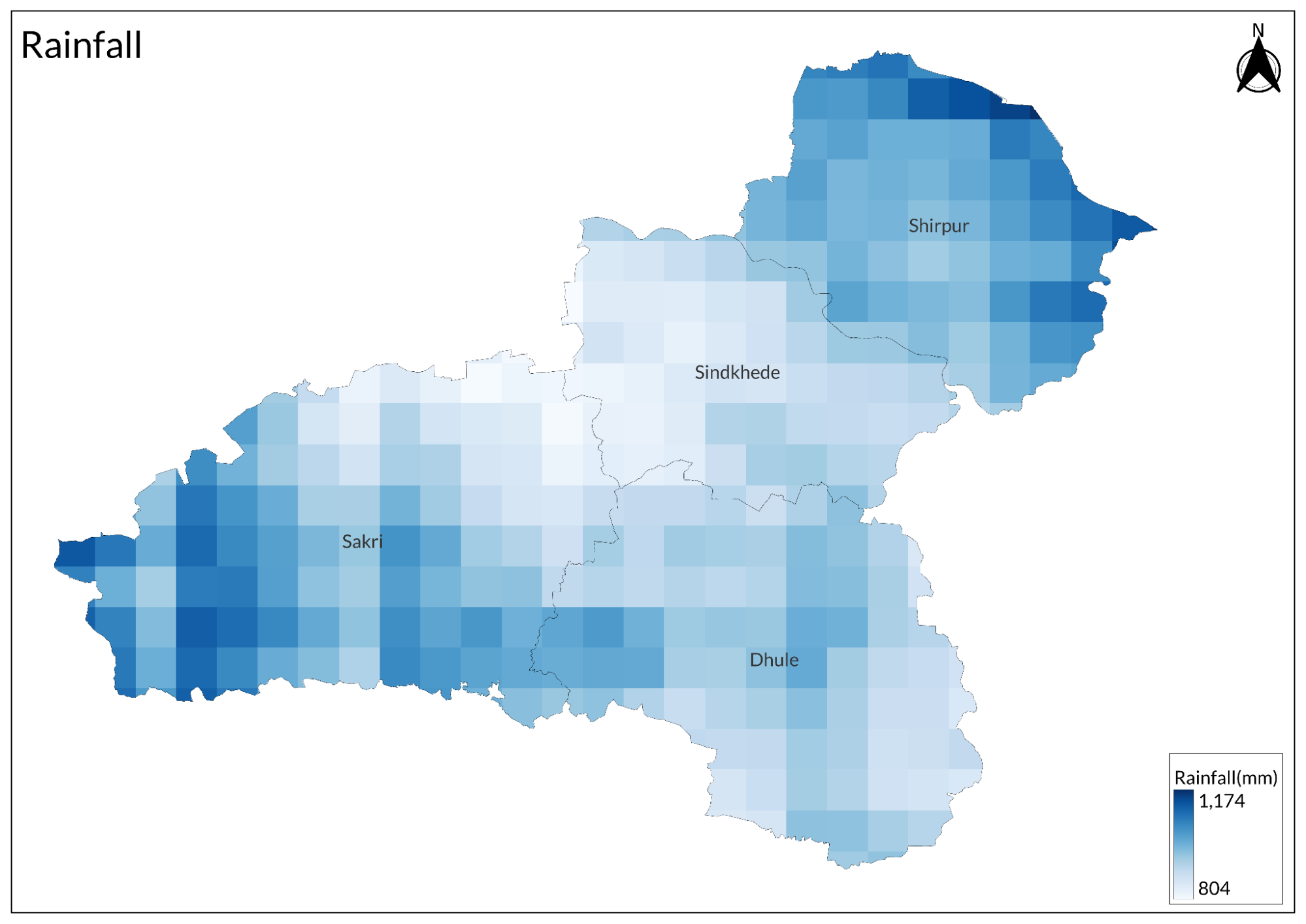

Despite the resilience of its farming community, Dhule faces challenges due to its climatic conditions. According to the NABARD report (2023-24), Dhule receives an average annual rainfall of 566 mm. Still, with three out of four blocks located in rain-shadow areas, the region is highly susceptible to drought. As a result, 424 of its 681 villages are classified as drought-prone.

Crop Cultivation

According to a NABARD report (2023-24), Dhule spans a geographical area of 7.19 lakh hectares, with 5.24 lakh hectares of cultivable land. The district's agricultural patterns are heavily shaped by its diverse agro-ecological zones. These zones play a crucial role in determining the types of crops that can thrive in the region, but they also underscore the vulnerabilities farmers face.

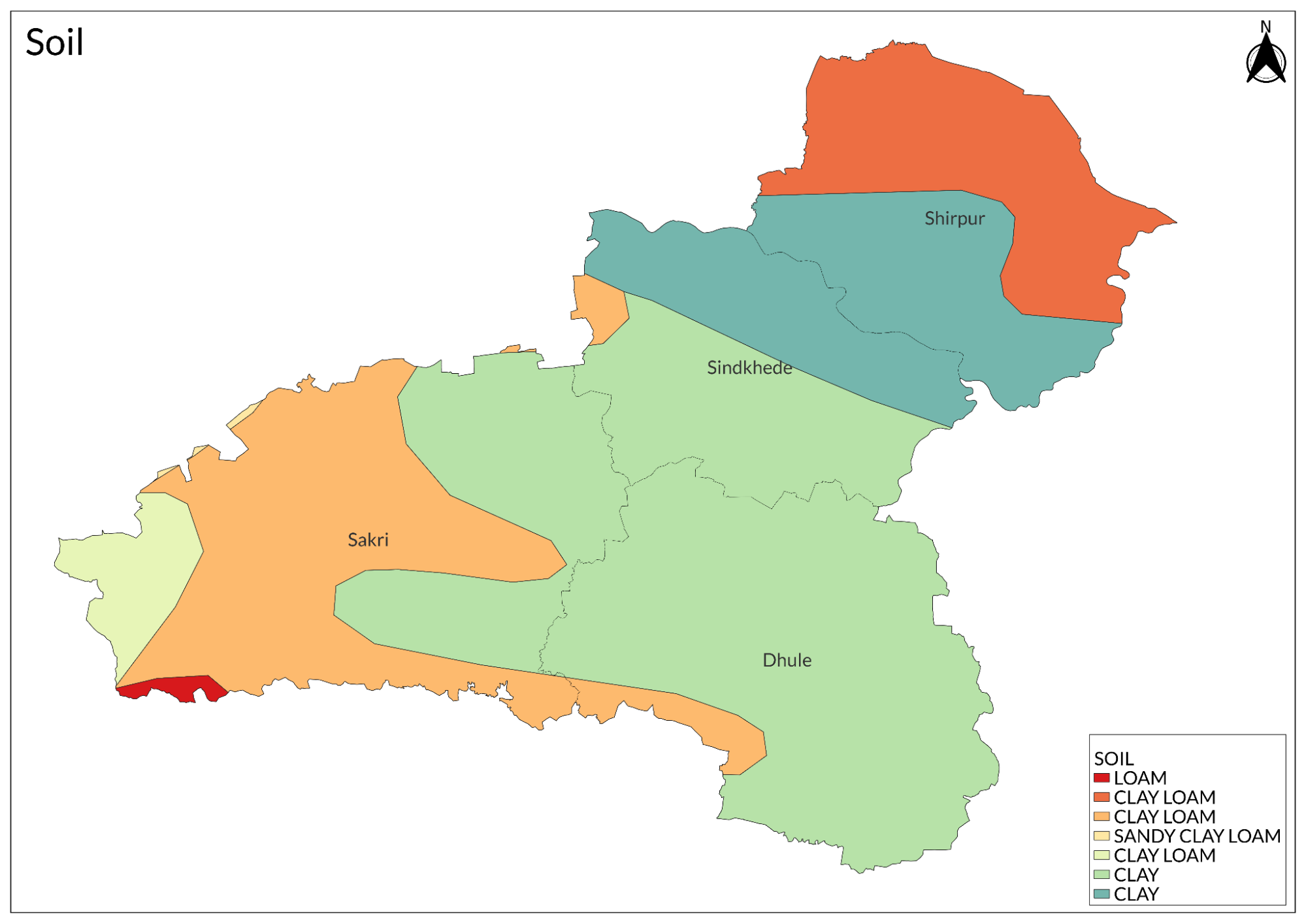

The district is primarily divided into three agroecological zones, each with its unique agricultural potential and challenges. The ‘Scarcity Zone’, which includes Dhule, Shindkheda, and the eastern part of Sakri, is marked by high dependence on the monsoon season for irrigation. Agriculture in this zone is particularly vulnerable to the erratic rainfall patterns of the region. Farmers in this area face the compounded challenge of recurring droughts, often leading to crop failures and economic distress.

Shirpur taluka, which falls under the 'Assured Rainfall Zone', is reported to experience more consistent rainfall, potentially offering a more stable environment for agriculture. This zone plays a role in supporting food security in Dhule, as its relatively reliable rainfall may encourage a more diverse cropping system. Conversely, the western part of Sakri taluka is characterized by high rainfall and fertile, medium-to-deep black soils, which may provide favorable conditions for a wide range of crops, potentially making it one of the more productive agricultural areas in the district.

The district’s soil composition varies, with light, medium, and black soils found in different areas. These soil types appear well-suited for growing drought-resistant crops such as jowar, bajra, maize, and cotton, which are commonly cultivated in Dhule.

In terms of crop production, cotton remains the dominant crop in Dhule, especially during the Kharif season. In the 2022-23 season, cotton covered approximately 2.35 lakh hectares, although this area has seen some fluctuations over recent years. Other major Kharif crops include bajra, maize, jowar, groundnut, and pulses like moong, urad, and tur. Finger millet, or Nagali, which is known for its ability to withstand dry conditions, is also widely grown in the region.

In the Rabi season, wheat and gram are primarily cultivated, while sunflower, an oilseed, is grown during the summer months. A range of vegetable crops, including chili, brinjal, bhendi (okra), peas, beans, onions, and tomatoes, are also grown extensively. These vegetables play a significant role in the district’s agricultural economy, contributing to both local consumption and regional markets.

Dhule’s climate is said to be increasingly favorable for horticultural crops. Over the years, fruit crops like pomegranate, guava, custard apple, and ber (Indian jujube) have become more common. These fruits are diversifying the agricultural portfolio of the region and providing alternative income sources for farmers. Among these, bananas and mangoes are the most widely cultivated, while lime, sweet lime, and oranges also contribute significantly to the local economy.

Sugarcane has historically been an important cash crop in Dhule, particularly in the Sakri taluka. According to records from the district’s Gazetteer (1974), in 1952-53, Sakri accounted for 68% of the total area under sugarcane cultivation. By 1961-62, this share had reduced to 40%, although the area of sugarcane cultivation in Sakri remained the highest in the district. This shift reflects the spread of sugarcane cultivation to other talukas, likely driven by the expansion of irrigation infrastructure and the increasing availability of water resources, as noted in the gazetteer.

The range of crops grown in Dhule, from staple cereals to horticultural fruits, highlights the district's agricultural diversity. This diversity reflects the adaptability and resilience of local farmers, who continuously navigate both traditional practices and modern techniques to maintain productivity and sustain the region's agricultural economy.

Agricultural Communities

The agricultural landscape of Dhule is shaped by a variety of farming communities, each with its unique traditions and practices. Broadly, the farming communities in Dhule can be categorized into two main groups, each associated with different geographic regions and agricultural methods. The first group comprises indigenous communities residing in the district's hilly regions, while the second group includes local husbandmen farming in the plains and more fertile areas.

According to the district Gazetteer (1974), farming in the hilly areas, particularly in the northern Satpuda and southern Satmala ranges, is often practiced using traditional methods passed down through generations. These regions are home to indigenous communities such as the Bhils, Dhanka, Gamit, Kokna, Naikda, and Pardhi. These communities rely not only on farming but also on gathering wild fruits, hunting, and wood-cutting to sustain their livelihoods. Their agricultural practices are generally less mechanized and closely tied to the natural environment.

In contrast, Dhule's plains and fertile regions are home to local husbandmen from communities like the Marathas, Gujars, Rajputs, and Malis. Interestingly, Gujar farmers are particularly distinguished by their long-standing tradition of using horses in the fields, which is quite unusual and striking. On the other hand, the Malis continue to follow the traditional bagait or mala method of cultivation, a practice passed down through generations. This deep connection to their land and methods underscores the agricultural customs that shape the identity and way of life of these communities.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

The agricultural practices of Dhule have been shaped by its distinctive landscape. Nestled between the Satpura and Satmala mountain ranges, the region's farming systems can perhaps be broadly categorized into two approaches: farming in the hilly areas and the plains. Over time, these practices have evolved, influenced by the natural environment and changing policies.

Farming in Hilly Regions

Historically, it is noted in the district Gazetteer (1974) that farming in Dhule's hilly regions was largely dominated by a traditional agricultural practice known as dalhi or kumri. This method involved clearing small patches of forest land by cutting and burning brushwood. After the first monsoon rains, crops like ragi, coarse grains, and sometimes bajri were sown. These crops were planted either in organized rows (regular lines) or scattered across the land (broadcast).

The "regular lines" method involved planting seeds in straight, even rows, ensuring equal spacing for the crops, while the "broadcast" method involved scattering the seeds randomly over the soil, allowing them to grow more chaotically. The latter is often seen in traditional farming systems with less intensive management.

After a few harvests, the land would be abandoned, and a new patch of forest would be cleared for cultivation. This form of shifting cultivation was once widespread, but due to modern agricultural policies and stricter forest regulations, its prevalence has sharply declined. However, the gazetteer mentions that the practice persisted, albeit on a smaller scale, in some dense forest areas.

The shift away from traditional practices can perhaps largely be attributed to programs initiated by the administration for farming communities living in the forests. As mentioned in the gazetteer, these programs aimed to move away from shifting cultivation and encourage settled agricultural practices. Settled farming involves farmers remaining in one location throughout the year to care for their crops and livestock. The shift from traditional farming methods to settled farming can likely be ascribed to the benefits of more consistent and organized agricultural practices, which are better suited for long-term sustainability and increased crop production.

Market Structure: APMCs

Dhule is home to four major Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), with several submarkets established over the decades. These markets help structure the agricultural trading system and provide farmers with a platform for selling their produce.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

|

1 |

Dhule |

1930 |

Bajirao Hiraman Patil |

|

2 |

Shirud |

1962 |

Bajirao Hiraman Patil |

|

3 |

Lamkani |

1965 |

Bajirao Hiraman Patil |

|

4 |

Boris |

1976 |

Bajirao Hiraman Patil |

|

5 |

Dondaicha |

1937 |

Narayan Bajirao Patil |

|

6 |

Shindkheda |

1949 |

Narayan Bajirao Patil |

|

7 |

Nardhana |

1945 |

Narayan Bajirao Patil |

|

8 |

Betavad |

1955 |

Narayan Bajirao Patil |

|

9 |

Sakri |

1962 |

Bansilal Vaman Baviskar |

|

10 |

Pimpalner |

1964 |

Bhushan Kailasrao Bacchav |

|

11 |

Nijampur |

1964 |

Bhushan Kailasrao Bacchav |

|

12 |

Shirpur |

1948 |

Narendrasing Pratapsing Sisodiya |

The major agricultural commodities traded in the district include wheat (husked), sorghum (jowar), maize, groundnut pods, and onions. In addition, Sakri APMC also deals with bulrush millet, while Shirpur APMC is known for trading sorghum, maize, gram, green gram, black gram, groundnut pods, soybean, and sesame.

These APMCs and submarkets are integral to the agricultural economy of Dhule, providing a structured marketplace for local farmers to sell their produce.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Govt. Of Maharashtra. 1974. District Gazetteers, Dhulia District. Gazetteers Dept. Mumbai.

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan: Dhule. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/te…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.