Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Women agriculturists

- Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

- Bail Pola

- Dhawara

- Yel Amavasya Puja

- Types of Farming

- Tomato Farming

- Mango cultivation and seed conservation

- Sunflower Cultivation

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- The post-harvest Jowar

- Use of Technology

- Natural Farming and Watershed programs

- Rejuvenation of Manjara River

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Galit Sansodhan Kendra (Oilseed Research Centre)

- Cotton Research Sub-Centre, Somnathpur

- College of Agriculture, Latur

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Problems Faced by Farmers

- Climate change and the plight of Latur

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

LATUR

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

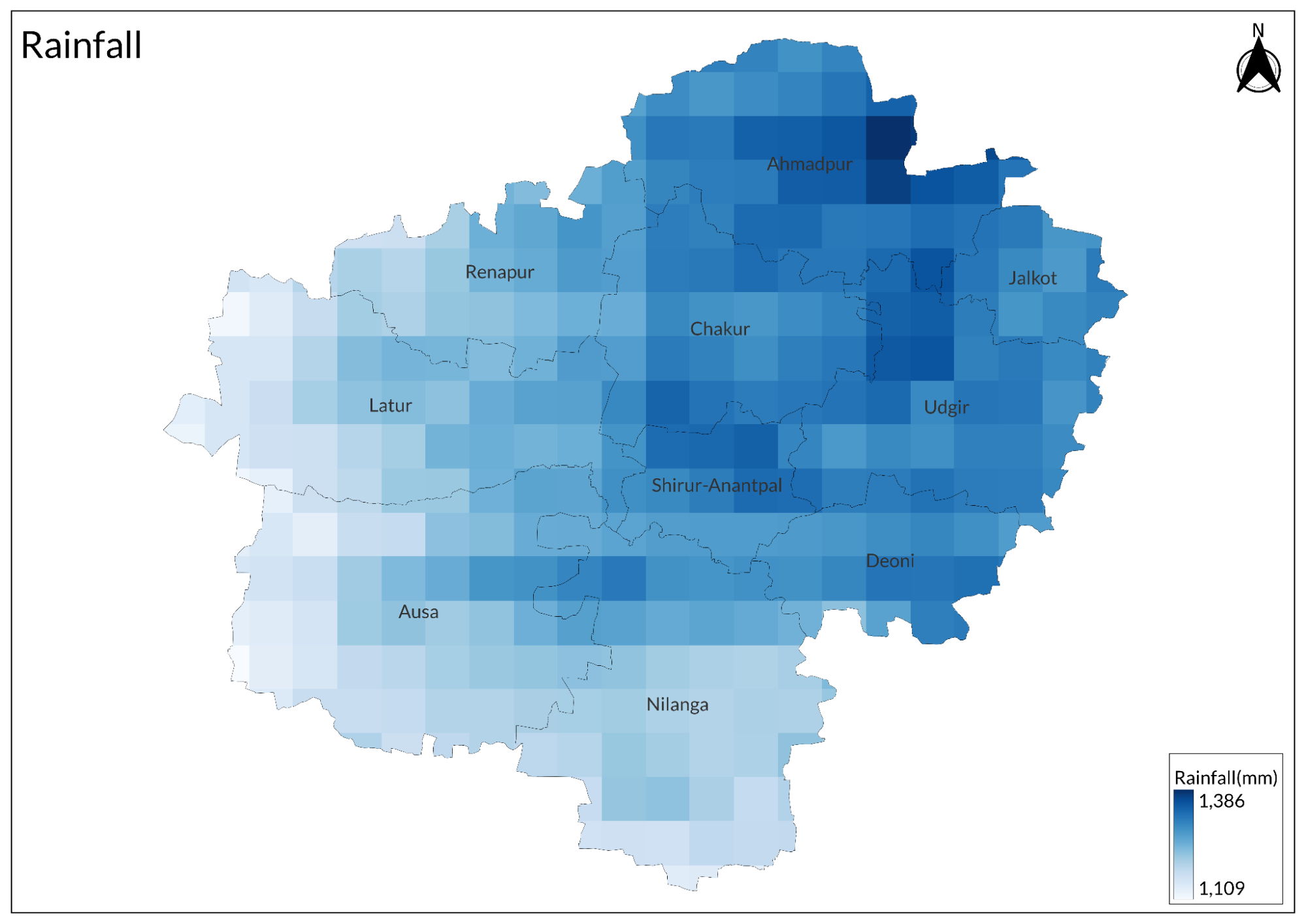

Latur is one of eight districts that lies in the Marathwada region in Maharashtra. Located in the assured rainfall zone in Maharashtra, the district is well-placed for agricultural activity. The district lies entirely inside the Deccan Plateau, it has a Hot Semi-Arid and the population is largely agrarian with major crops such as Soybean, Sorghum, and Pigeonpea. The district is also drained by rivers such as Manjra and its tributaries, the Terna, the Tawarja, and the Gharni, and other rivers such as Manar, the Tiru, and the Lendi, which belong to the Godavari drainage system.

Crop Cultivation

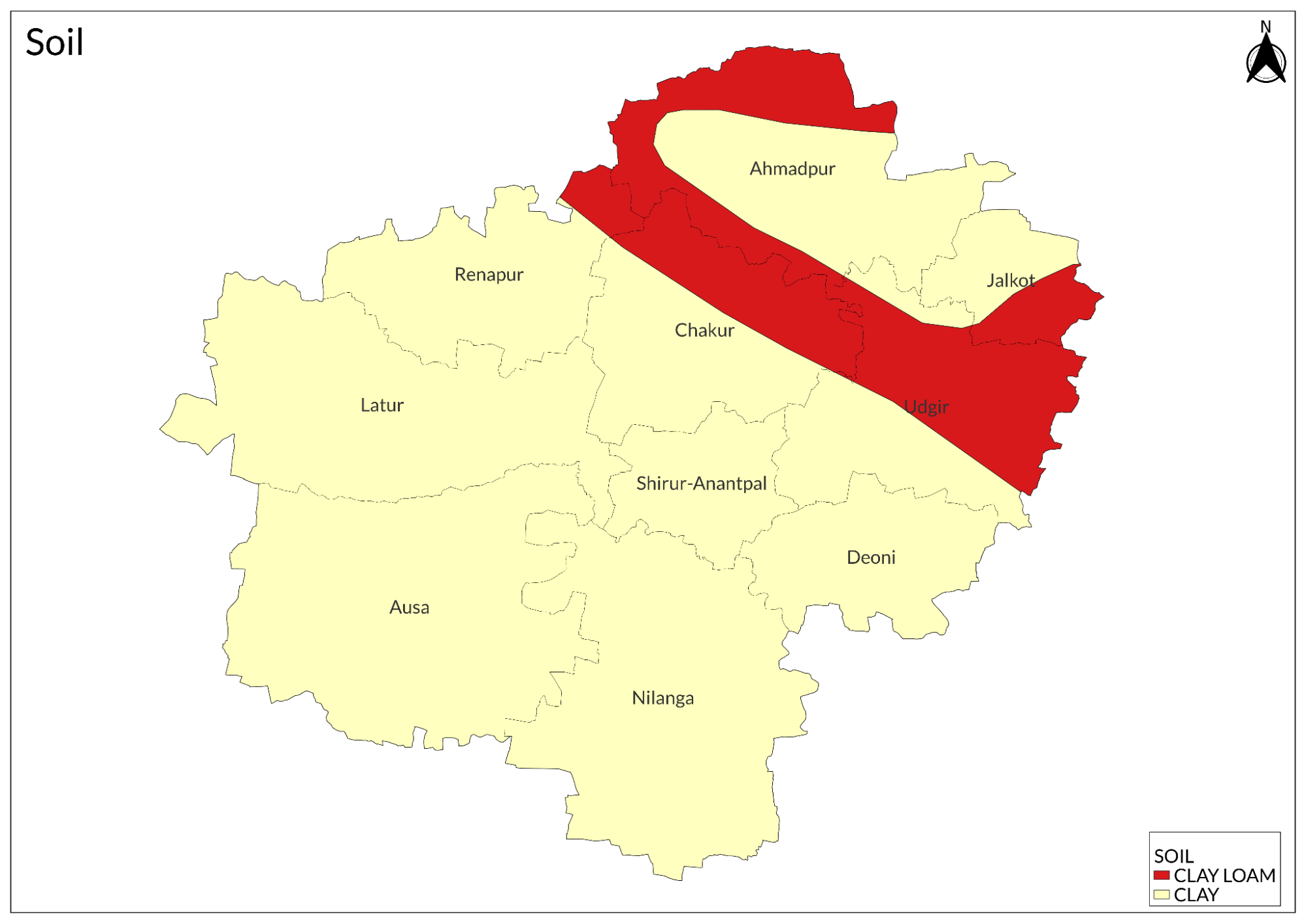

The agricultural landscape of the Latur district is shaped by various soil types, notably Shallow soils of light brown to dark grey-brown, Medium deep soils that are clay-loam to clayey in texture, and lastly deep soils that are again clayey in texture. These soils support a variety of Rabi crops such as Wheat, Sugarcane, Safflower, Sunflower, and Gram, Kharif crops such as Soybean, Kharif-Sorghum, Pigeonpea, Black Gram, and Green Gram and lastly Horticulture crops such as Fig, Mango, Sapota, Brinjal, Tomato, Papaya, Coriander, Tamarind and Pomegranate. A few crops, such as the Tamarinds from Panchincholi, the Gram from Borsuri, and the Coriander from Kasti, all received their respective GI tags in 2024.

Agricultural Communities

Several communities in the region have strong ties to agriculture. Kunbis and Kunbi sub-communities such as the Maratha Kunbis, Konkani Kunbis, Kale Kunbis, Khandeshi Kunbis, Talheri Kunbis, and Kshatriya Marathas are communities that are generally involved in cultivation, though they can also be found in other walks of life.

The Kaikadis, a denotified community originally from Telangana, have settled in the district and now take part in farming. The Mahadev Kolis, also known as Dongar Kolis, are another community active in agriculture and farm labour.

Other groups, such as the Malis — who grow and sell fruits, vegetables, and flowers — along with Matangs, Mahars, and some local Muslims, also contribute to the district’s agricultural workforce.

Women agriculturists

In 2021, it was reported that approximately 1,38,000 women in Marathwada successfully doubled their incomes through organic farming. One notable figure among them is Santoshi Survase from Mamdapur in Latur, who in 2018 began experimenting with organic farming techniques she had recently learned. She planted various crops on one acre of land, and within a year, her efforts yielded jowar, tomatoes, moong, and brinjals, even amid drought-like conditions. Over time, Santoshi took charge of the entire five-acre family farm, making all the farming-related decisions and managing the financial needs of her husband and two children. By 2021, the Survase family’s annual income had risen to Rs 3,00,000, a remarkable 72% increase from 2018.

Inspired by Santoshi’s success, nearly 20 women in her village adopted the same organic farming technique known as the ‘One Acre Model.’ This model, developed by Swayam Shikshan Prayog (SSP)—a Pune-based non-profit dedicated to sustainable community development and women’s empowerment—has been transformative. Across the Marathwada region, one of the most drought-affected areas in India, the one-acre model has thrived, helping countless women achieve financial stability and sustainability over the past decade.

Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

Bail Pola

On the last day of Shravan, bulls are bathed early in the morning. Their horns are then painted and adorned with ornaments; they are also given good food and are allowed to rest for the entire day. Pola is celebrated in almost every region of Maharashtra and can be seen as a festival that celebrates the efforts and hard work of the farmers, especially the bulls. home from the fields.

Dhawara

Dhawara is a cherished tradition in the local farming culture, marking the celebration of a successful harvest with a sacred meal. The preparations for Dhawara begin on the new moon of Diwali, a day dedicated to worshiping the Pandavas, the five legendary brothers from the Mahabharata. In the fields, five small stones are selected and painted with Chuna (limewash), symbolizing the Pandavas.

As part of the ritual, wheat flour dough is shaped into various forms, such as plain balls, fruits, and lamps, before being steamed. These, along with dried dates, dry coconut, Ambil (a tangy buttermilk preparation infused with chilies and coriander), Kadhi (a tempered chickpea-buttermilk curry), and Wadya (steamed gram flour cakes), are offered as Naivedya (a devotional offering). A Morva (medium-sized earthen pot) and Shendur (a sacred red powder) are also placed near the symbolic Pandavas.

In keeping with tradition, five stacks of Jowar Pachundas (bundles of harvested sorghum) are arranged upright before the stones. A lamp is then placed inside the Morva and lit as a mark of reverence. At dusk, the Morva is carefully buried near the painted stones, symbolizing the completion of the Dhawara ritual and expressing gratitude for the harvest.

Yel Amavasya Puja

A puja similar to Dhawara is performed during Yel Amavasya (the new moon night that falls in January). The Yel Amavasya puja is still a common and notable festival related to farming in the Ashmak region, which comprises areas of present-day Maharashtra and Karnataka.

Types of Farming

Tomato Farming

Tomatoes are usually grown on specified plots of land. The commonly grown varieties of tomatoes are Arka Abha, Arka Saurabh, Pusa Gaurav, Angurlata, Pant Bahar, Ratna, and Rupali. Tomatoes are usually sown in March-June. As tomatoes typically take 100 to 120 days to harvest after planting seeds, multiple crops can be grown in a single season. A few farmers who have huge land holdings also plant multiple varieties of tomatoes in a single season. One of the most important processes is that of staking, in which wooden poles are dug into the ground to support the plants and prevent them from coming into contact with the soil. This prevents the Tomatoes from spoiling.

Mango cultivation and seed conservation

In 2023, Mahadev Gomare, a farmer, seed conservationist, and natural farming trainer with The Art of Living NGO, launched a mission called Ek Laksh Aam Vruksh (One Lakh Mango Trees). The initiative aimed to plant one lakh mango trees while promoting seed conservation and natural or organic farming practices. Gomare began by encouraging farmers and residents of Latur to collect and donate mango seeds. These seeds were then treated with bio-enzymes at a nursery on Gomare’s farm, where they were nurtured into saplings and grafted to produce Kesar mango varieties for distribution to farmers.

This initiative serves multiple purposes: mango trees help arrest soil erosion, conserve water due to their low water requirements—an essential factor in water-scarce Latur—and provide a sustainable income for farmers. Once the trees begin bearing fruit, they can offer a reliable source of income, with mango plantations potentially generating earnings of Rs. 4-5 lakh annually, effectively serving as a "pension plan" for farmers.

Sunflower Cultivation

Sunflower is cultivated in both the kharif and rabi seasons in the district. It is mainly grown in the talukas of Udgir, Ausa, Latur, and Ahmedpur. The district’s climate and soil are generally suitable for sunflower cultivation.

The land is first ploughed and then tilled twice to prepare the seedbed. Seeds are sown in rows, and after 10 to 16 days, excess plants are removed to give the remaining plants enough space to grow and develop flowers — a practice locally known as viralni. Weeding is done two to three times during the growing period to maintain healthy growth.

The crop is ready for harvest in about three and a half to four and a half months. After harvesting, the flowers are dried and beaten with sticks to separate the seeds.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Various traditional practices are prevalent in the district as it has a deep-rooted agrarian society.

A few practices though stand out such as the use of Shendanyachi Pend (which literally translates to Groundnut Cake) an organic manure. Malni — a method where bulls are used to separate the seeds of crops such as wheat, sorghum, pearl millet, and black gram from their husks — remains in practice as well. The Tifan, a traditional tool for sowing seeds, is also widely used by farmers in the region.

The post-harvest Jowar

During the rabi season, jowar stalks are uprooted while still green to prevent grain shedding in the field. The harvested stalks are tied into bundles, marking the beginning of the threshing process. This takes place in the Khale, a specially prepared circular threshing floor. The Khale is meticulously rammed and watered to ensure a smooth, solid, and sturdy surface for threshing. At its center, a Tivda, a twelve-foot cylindrical wooden pole, is erected, around which bullocks are tied and made to move in circles, trampling the harvested cobs to separate the grains.

Fresh green jowar cobs, still moist, are laid out on the Khale to dry. They are tossed around using a Datala, a type of farm fork, ensuring each cob gets adequate sunlight exposure. Once dried, the cobs are again spread across the Khale, and bullocks are set to circle and trample over them, further loosening the grains from the husks. The bullocks' muzzles were tied with cotton cloth to prevent them from eating the cobs and jowar. The separated grains are collected into heaps and then winnowed, using the wind to filter out unwanted husk and debris.

The intricate task of manually separating good kernels from husks, particles, and dust was traditionally carried out by members of the Mang community. They used Haatni, brooms crafted from the long, thin stems of the Aghada plant (Achyranthes aspera), a medicinal herb also used in the auspicious months of Shravan and Bhadrapad for worshiping Bhagwan Ganesha. These brooms helped efficiently sift hollow cobs, good kernels, and spoiled kernels. Hollow cobs were beaten once more to extract any remaining grains, while spoiled kernels were reprocessed to remove impurities and salvage usable jowar. Through this meticulous process, piles of clean, white jowar were separated and made ready for storage or sale.

Use of Technology

The use of modern technology in agriculture has been on the rise for several decades, helping farmers enhance productivity and reduce losses. In 2016, Malan Raut from Nagarsora village in Aura taluka installed a borewell on her 2.5-acre plot, enabling her to cultivate 25 varieties of vegetables, including brinjal, ladies’ fingers, and greens, alongside fruits like pomegranate, sitaphal (custard apple), and jamun (black plum). However, her success was soon threatened by wild animals like deer and wild boars, which destroyed her crops at night, causing severe financial losses.

Relief came in April 2019 when Katidhan, a Bengaluru-based organization specializing in agricultural tech solutions, introduced Parabraksh, a solar-powered autonomous flashlight designed to deter wildlife without harm. The device, powered by a small solar panel, lithium-ion battery, and LED lights, created random blinking patterns across the field to scare away animals. Over two years, Parabraksh proved to be 90% effective in protecting Raut’s crops, helping her earn nearly ₹90,000 annually by selling her produce.

Alongside technological interventions for crop protection, farmers in Latur have increasingly adopted modern agricultural inputs to boost yields. The shift towards high-yielding variety (HYV) seeds has been particularly noticeable, with farmers cultivating Jowar (Sorghum) using varieties like PJ-4, PJ-8, PJ-16, and M 15-1, while Wheat farmers use HYV seeds such as N-59, HY-65, Niphad-59, Kalyansona-1593, and HD 2021. These improved seed varieties have significantly benefited farmers by increasing production and ensuring better resilience to climate variations.

The growing adoption of advanced farming techniques, improved seed varieties, and innovative technology-driven solutions highlights a transformative shift in agriculture. Farmers across Maharashtra are leveraging both traditional knowledge and modern advancements to tackle agricultural challenges, improve productivity, and safeguard their livelihoods.

Natural Farming and Watershed programs

Latur lies in the drought-prone Marathwada region of Maharashtra. This makes Natural farming and Watershed management a necessity for the district as these practices can aid the district in its long fight against drought and scarcity, and they can also shield the farmers from economic hardships.

A government official in 2023 stated that a firm based in Nalegaon taluka set out to carry out organic farming on 300 hectares of land under the aegis of the state agriculture department. Fifteen clusters of farmers were formed for this initiative, each of which is set to get Rs 10 lakh over the next three years to cultivate crops in Chakur tehsil here without using chemicals. Each cluster consists of 20 farmers from Nalegaon, Ajansonda (Khurd), Sawantwadi, Hatkarwadi, Ukachiwadi, Hudgewadi, Limbalwadi, Sugaon, and Gharni villages.

In a noteworthy initiative, Volkswagen, the German automobile manufacturer, in collaboration with the International Association for Human Values (IAHV), launched a watershed management program in the Nashik district. Volkswagen India allocated Rs 1.34 crore for the project, which focuses on restoring and sustaining natural resources in a cluster of villages in Latur such as Lasona, Indral, Wadmurambi, and Ambanagar.

The initiative aims to establish an integrated and sustainable natural resource management model through a unique combination of social, technical, and financial strategies. The project adopts a structured approach that includes community mobilization and capacity building, artificial groundwater recharge, soil and water conservation, farmer field schools, afforestation, and leveraging government schemes. This comprehensive strategy is designed to address the challenges of resource depletion while empowering local communities to sustainably manage their natural resources.

Rejuvenation of Manjara River

Marathwada, a region frequently plagued by water scarcity, faces compounding challenges of debt and crop failure, leading to severe agrarian distress. However, in Latur, a transformative movement led by agriculturist Mahadev Gomare and a determined group of villagers has begun to reverse this grim narrative, offering hope to farmers in the region.

The journey toward change began in 2013 with the rejuvenation of the Manjara River, a 143-km lifeline for Latur, providing water to over 900 villages. This effort extended to reviving its tributaries, including the Gharni, Tamarja, and Terna rivers. Over time, this grassroots initiative evolved into the larger "Jal Jagruti Abhiyan," a movement involving farmers, local communities, and district authorities, all working together to combat the region’s chronic water issues.

A key aspect of the campaign was removing silt that had obstructed the flow of the rivers. Gomare explains that silt accumulation, caused by eroded soil from forests and fields flowing into rivers and reservoirs, severely hampers groundwater recharge. Over 9 lakh cubic meters of silt were removed from the Manjara River, restoring its vitality. The excavated silt was repurposed to level adjacent farmland, boosting agricultural productivity through sharecropping initiatives.

Gomare credits traditional knowledge as the foundation of the movement. By combining age-old wisdom with modern interventions, his team introduced desilting measures and gabion structures in select villages as a pilot project. Encouraged by initial success, more villages joined the initiative, pooling resources into a community fund to expand the effort. The result was not only a rejuvenated river system but also a marked improvement in the region's groundwater levels.

The project’s success spurred a series of agricultural advancements. Farmers embraced natural farming, afforestation, and climate-resilient practices to increase productivity while conserving resources. Agroforestry and social forestry initiatives were launched to green the area and protect it from future droughts. Volunteers from Gomare’s team continue to guide farmers through the transition to sustainable practices.

Today, the Manjara River and its tributaries stand as symbols of the region’s revival, with water levels showing significant improvement. For the 1.5 lakh farmers in Latur who rely on these resources, these interventions have not only increased crop yields but also restored hope for a more sustainable future.

Institutional Infrastructure

Latur has an average developed agricultural infrastructure, which includes 11 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 138 godowns, 15 cold storages, 5 soil testing centers, 333 farmers clubs, 6 plantation nurseries, and approximately 2776 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. There is also one Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) supporting agricultural extension services in the region. In addition to this, there are 19 commercial banks, 1 Regional rural bank, and District Central Cooperative bank, 43 branches of Maharashtra Gramin Bank, and 586 Primary Agr. Cooperative Societies. Latur also has 13 sugar factories.

In addition to this, there are various large-scale and medium-scale irrigation projects in the districts, such as the Manjara project, which was inaugurated in 1986, Dharni Dam, built on the Dharni river in Jogala, Tiru Dam, inaugurated in 1979, and Tawarja, inaugurated in 1986. Other than these, there are various other projects in the district as well.

Galit Sansodhan Kendra (Oilseed Research Centre)

Established in 1956, this centre in its earlier days carried out research on Peanuts, Niger Seeds and Sesame after 1970 it only focused on Peanuts and then later on in 1989, it added Sunflower to its research ambit as well. The centre has been instrumental in developing newer disease-resistant varieties of Sunflower, Sesame, Safflower, Peanuts, and Flaxseeds.

Cotton Research Sub-Centre, Somnathpur

This centre was established by the Central Institute of Cotton Research in 1934. In 1962, it was moved to its current location in Somnathpur, Udgir Taluka. Crops such as Sal, Cotton, and Sorghum and their various varieties, benefits, and demerits are researched at the centre. Since it is only a Sub-Centre, the research conducted here is sent to the Cotton Research Centres at Nanded and Parbhani.

College of Agriculture, Latur

The College of Agriculture, Latur, was established in 1987 with the primary objective of offering higher education in the form of a B.Sc. (Agriculture) degree to Village Level Workers (VLWs) employed by the Department of Agriculture under the Training and Visit (T&V) system. Initially, the intake capacity was limited to 35 candidates. In 1989, the institution was expanded to include a regular 10+2 pattern B.Sc. (Agriculture) program of four years, accommodating 64 students. Subsequently, the intake capacity was further increased to 94 students, with provisions made to admit in-service candidates who had passed their XII (Science) education on deputation.

In 2002-03, the college introduced a postgraduate program leading to M.Sc. (Agriculture) degrees across six disciplines: Agronomy, Agricultural Botany, Agricultural Entomology, Plant Pathology, Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, and Agricultural Economics, each with an intake capacity of six students. This program was further enhanced in the academic year 2005-06 with the inclusion of four additional disciplines: Horticulture, Animal Husbandry & Dairy Science, Agricultural Meteorology, and Agricultural Extension Education. These developments reflect the college’s commitment to providing comprehensive and advanced education in agricultural sciences.

Market Structure: APMCs

There are 11 APMCs in the district. The Shegaon and Malkapur APMCs are the oldest ones in the district. Wheat (Husked), Jowar, Maize, Gram, Pigeon Pea, Cotton, Soybean, Green Gram, Safflower, Sunflower, etc., are some of the important commodities that are sold at these markets.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1. |

Ahmedpur |

1960 |

MANCHAKRAO MOHANRAO PATIL |

3 |

|

2. |

Aurah Shahjani |

1997 |

Narshing Shyamrao Biradar |

NA |

|

3. |

Ausa |

1982 |

Chandrasekhar Bhaurao Sonwane |

1 |

|

4. |

Chakur |

1987 |

Nilkanth Virnath Mirkale |

NA |

|

5. |

Devani |

2008 |

NA |

1 |

|

6. |

Jalkot |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

7. |

Latur |

1931 |

Jagadish Bavane |

2 |

|

8. |

Nilanga |

1961 |

Shivkumar Chinchansure |

1 |

|

9. |

Renpur |

1998 |

Umakant Khalangre |

NA |

|

10. |

Shirur Anantpal |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

11. |

Udgir |

1946 |

Shideshwer Gunwantaro Patil |

1 |

Problems Faced by Farmers

Agriculture in Latur is an arduous occupation. Farmers face problems such as erratic weather, flooding, hailstorms, and droughts, which visibly lead to an agrarian crisis. This, paired with a debt trap, leads to farmers’ suicide, which is pretty common not only in Latur but also in the larger Marathwada region. In 2023, around 51 farmers had committed suicide in the district, which alone dictates the somber situation of the farmers of Latur.

Climate change and the plight of Latur

Latur presents an interesting case, the district has been facing torrential rain and hailstorms for a decade now. The district has also seen a drop in the number of annual rainy days, while seeing an increase in the count of hotter days. In 1960, for instance, a farmer could expect at least 147 days annually that would see temperatures of 32° C or above; in 2019, the number had risen to 188, with projections saying that the number might further increase to 211 in the next 15-20 years.

These increased ‘hot days’ also enable droughts. The district has been facing water scarcity since 2011, however, this situation got extremely precarious in 2015-16 when according to a report of the Godavari Marathwada Irrigation Development Corporation, 11 major irrigation projects, 75 medium irrigation projects, and 729 minor irrigation projects in the eight Marathwada districts have only four percent, five percent and three percent of live water storage respectively. An additional problem is posed by sugarcane, which is widely grown in the district. The crop is a water-intensive crop and uses about 90% of the district’s total water available for irrigation. This severely affects the water resources of the district.

This scarcity of water was at its peak in 2016 when the government had to ferry water trains named ‘Jaldoot Express’ to help local farmers cope with extremely critical water crises. Water was so scarce that police security was provided to tankers and reservoirs, and the authorities imposed prohibitory orders at water distribution points.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

A.S Pathak. 2008.District Gazetteers, Latur District.Govt. of Maharashtra. Mumbai

ABP Majha. 2023.Tomato farming Selu Latur: टोमॅटोतून 1 कोटी कमाई,10 गुंठ्यावर टोलेजंग बंगला, पंडगे बंधूंची यशोगाथा. YouTube.

Agricultural Post. 2019.Volkswagen launches watershed management program in Latur.Agricultural Post.Com.https://agriculturepost.com/farm-inputs/volk…

Aishwarya Tripathi. 2023.Can a solar-powered flashlight address human-wildlife conflict?GaonConnection.com.https://www.gaonconnection.com/english/clean…

Anu.V, J. R Verma, A. Nivaskar. 2019.Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plan of Latur District, Maharashtra.Central Ground Water Board.

College of Agriculture, Latur.About Us.Coal.Vnmkv.ac.n

Gopi Karelia. 2021.How 1,38,000 Women Farmers In Drought-Prone Marathwada Doubled Their Incomes.TheBetterIndia.comhttps://thebetterindia.com/258354/maharashtr…

http://researchjournal.co.in/upload/assignments/3_347-349.pdf

https://coal.vnmkv.ac.in/Home/AboutUs

https://krishijagran.com/success-story/ek-laksh-aam-vruksh-mahadev-gomare-and-the-art-of-living-revitalize-maharashtras-mango-legacy-through-sustainable-farming-in-latur/

https://science.thewire.in/economy/agriculture/hailstorms-at-43-c-wreck-farming-in-latur/

https://www.business-standard.com/industry/agriculture/685-farmer-suicides-in-marathwada-so-far-agri-min-s-home-district-on-top-123091200124_1.html

https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/cover/latur-shows-the-way-for-marathwada-farmers/article33868708.ece

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6cfhJ-yHDw

ICAR. 2017.MAHARASHTRA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: LATUR.ICAR - CRIDA - NICRA.

K.T. Sonar, R.B. Changule, B.B. Mane, G.P. Gaikwad .2012.Economics of Rabi tomato production in Latur district of Maharashtra. Vol. 3, no. 2.Internationl Research Journal of Agricultural Economics and Statistics.

Murali Krishnan. 2021.Latur shows the way for Marathwada farmers.The Hindu.

N. Jamwal, Jitendra, R.Mahapatra, S.Venkatesh, K. Bahuguna, K. Pandey. 2016.In-depth coverage: Drought, but why.DownToEarth.Org.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/agriculture/i…

NABARD. 2023-24.Potential Linked Credit Plan:Latur.Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

Parth M.N. 2019.Hailstorms at 43° C Wreck Farming in Latur.ScienceTheWire.

PTI. 2023.5 clusters of farmers to carry out organic farming on 300 hectares in Latur.Mid-Day.com.https://www.mid-day.com/news/india-news/arti…

PTI. 2023.685 farmer suicides in Marathwada so far; agri min's home district on top. Business Standard.

Shahu Patole. 2024.Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada, Anna he apoorna Brahman. Harper Collins.

Shivam Dwivedi. 2024.‘Ek Laksh Aam Vruksh’: Mahadev Gomare and The Art of Living Revitalize Maharashtra's Mango Legacy Through Sustainable Farming in Latur.Krishi Jagran.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.