Contents

- Healthcare Infrastructure

- The Three-Tiered Structure of the District

- Age-Old Practices & Remedies

- Major Epidemics and Outbreaks in the District

- The Bombay Plague

- COVID 19

- Sanitation | Cleanliness & Public Toilets

- Graphs

- Healthcare Facilities and Services

- A. Public and Govt-Aided Medical Facilities

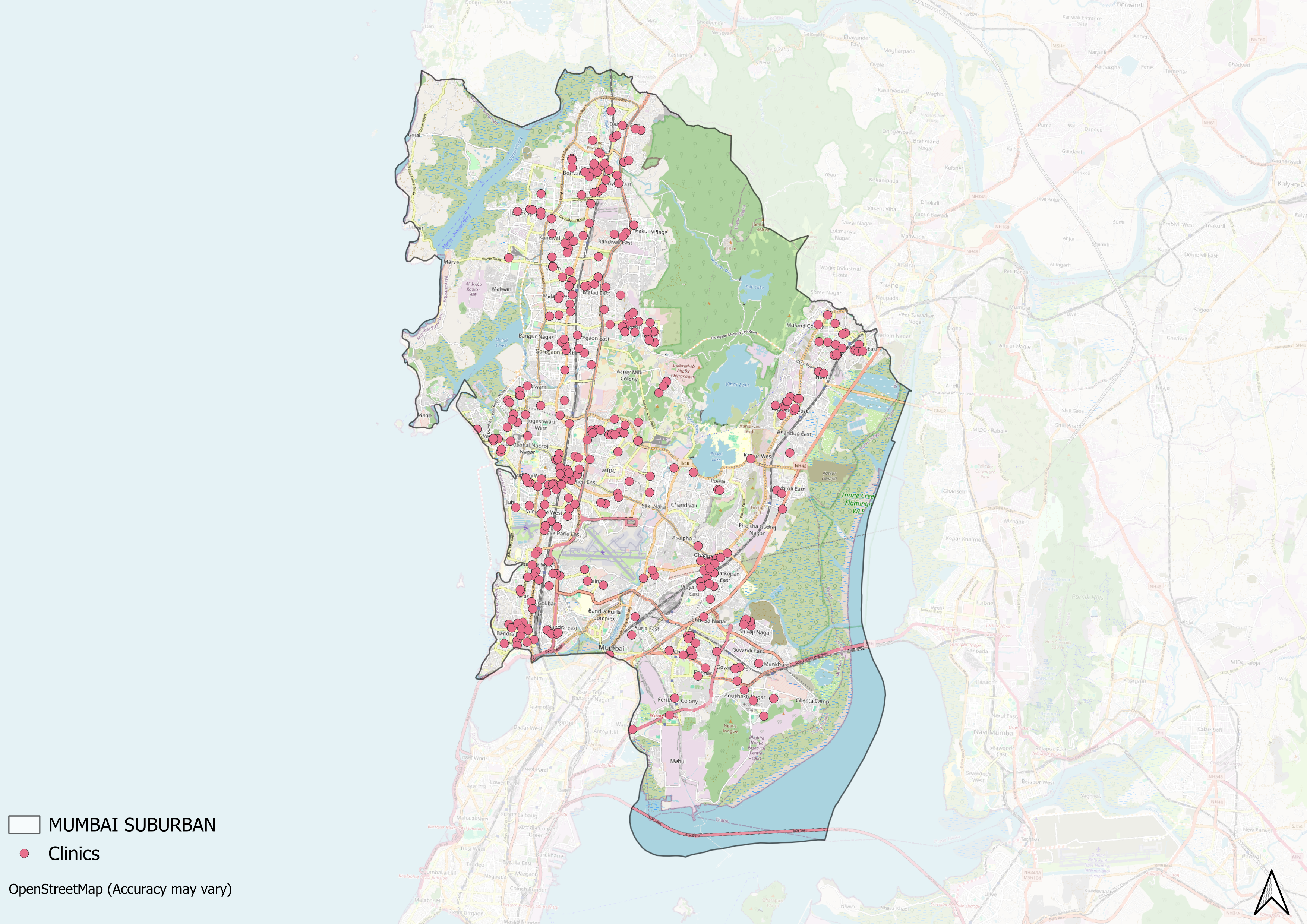

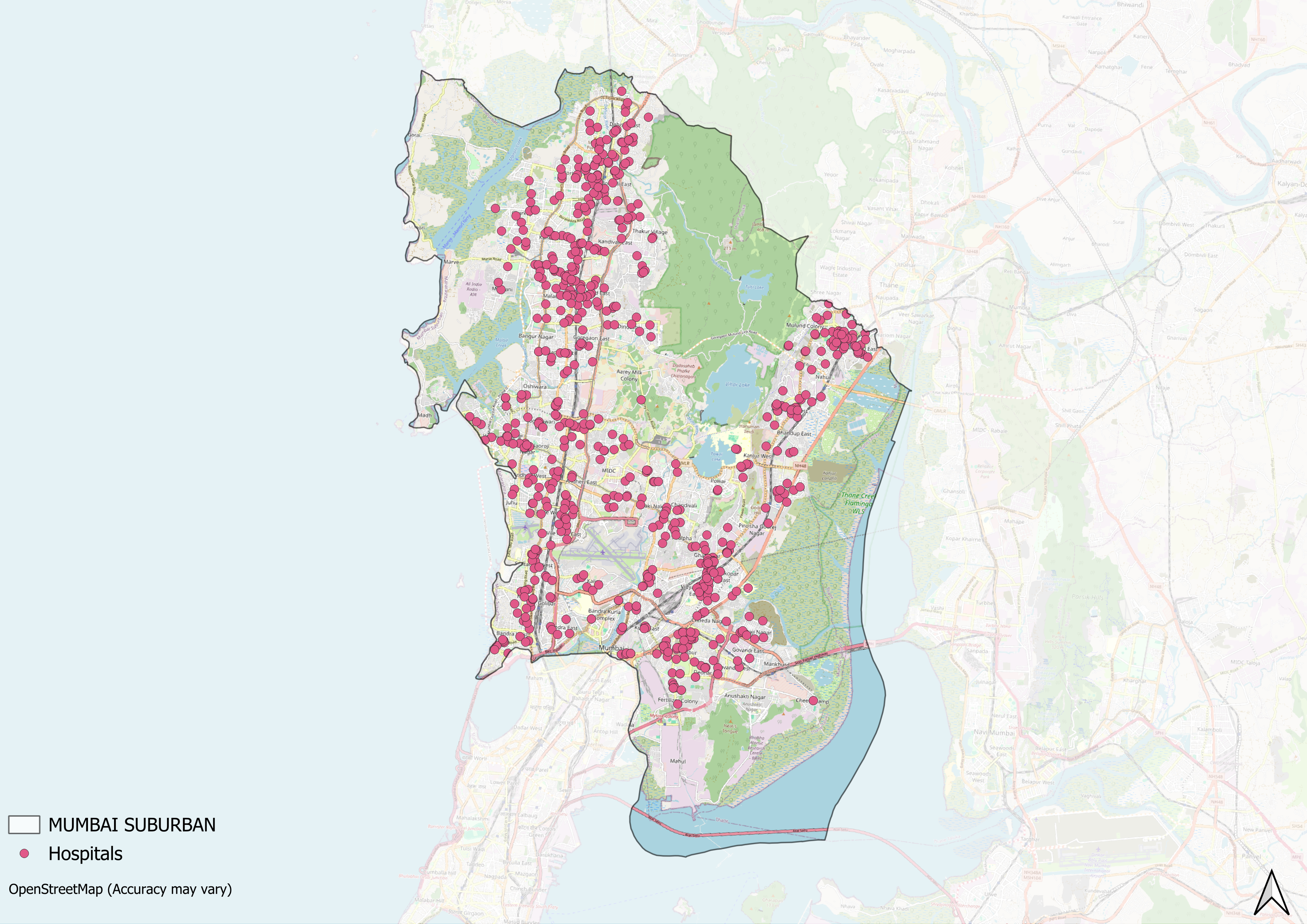

- B. Private Healthcare Facilities

- C. Approved vs Working Anganwadi

- D. Anganwadi Building Types

- E. Anganwadi Workers

- F. Patients in In-Patients Department

- G. Patients in Outpatients Department

- H. Outpatient-to-Inpatient Ratio

- I. Patients Treated in Public Facilities

- J. Operations Conducted

- K. Hysterectomies Performed

- L. Share of Households with Access to Health Amenities

- Morbidity and Mortality

- A. Reported Deaths

- B. Cause of Death

- C. Reported Child and Infant Deaths

- D. Reported Infant Deaths

- E. Select Causes of Infant Death

- F. Number of Children Diseased

- G. Population with High Blood Sugar

- H. Population with Very High Blood Sugar

- I. Population with Mildly Elevated Blood Pressure

- J. Population with Moderately or Severely High Hypertension

- K. Women Examined for Cancer

- L. Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption

- Maternal and Newborn Health

- A. Reported Deliveries

- B. Institutional Births: Public vs Private

- C. Home Births: Skilled vs Non-Skilled Attendants

- D. Live Birth Rate

- E. Still Birth Rate

- F. Maternal Deaths

- G. Registered Births

- H. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- I. Institutional Deliveries through C-Section

- J. Deliveries through C-Section: Public vs Private Facilities

- K. Reported Abortions

- L. Medical Terminations of Pregnancy: Public vs Private

- M. MTPs in Public Institutions before and after 12 Weeks

- N. Average Out of Pocket Expenditure per Delivery in Public Health Facilities

- O. Registrations for Antenatal Care

- P. Antenatal Care Registrations Done in First Trimester

- Q. Iron Folic Acid Consumption Among Pregnant Women

- R. Access to Postnatal Care from Health Personnel Within 2 Days of Delivery

- S. Children Breastfed within One Hour of Birth

- T. Children (6-23 months) Receiving an Adequate Diet

- U. Sex Ratio at Birth

- V. Births Registered with Civil Authority

- W. Institutional Deliveries through C-section

- X. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- Family Planning

- A. Population Using Family Planning Methods

- B. Usage Rate of Select Family Planning Methods

- C. Sterilizations Conducted (Public vs Private Facilities)

- D. Vasectomies

- E. Tubectomies

- F. Contraceptives Distributed

- G. IUD Insertions: Public vs Private

- H. Female Sterilization Rate

- I. Women’s Unmet Need for Family Planning

- J. Fertile Couples in Family Welfare Programs

- K. Family Welfare Centers

- L. Progress of Family Welfare Programs

- Immunization

- A. Vaccinations under the Maternal and Childcare Program

- B. Infants Given the Oral Polio Vaccine

- C. Infants Given the Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) Vaccine

- D. Infants Given Hepatitis Vaccine (Birth Dose)

- E. Infants Given the Pentavalent Vaccines

- F. Infants Given the Measles or Measles Rubella Vaccines

- G. Infants Given the Rotavirus Vaccines

- H. Fully Immunized Children

- I. Adverse Effects of Immunization

- J. Percentage of Children Fully Immunized

- K. Vaccination Rate (Children Aged 12 to 23 months)

- L. Children Primarily Vaccinated in (Public vs Private Health Facilities)

- Nutrition

- A. Children with Nutritional Deficits or Excess

- B. Population Overweight or Obese

- C. Population with Low BMI

- D. Prevalence of Anaemia

- E. Moderately Anaemic Women

- F. Women with Severe Anaemia being Treated at an Institution

- G. Malnourishment Among Infants in Anganwadis

- Sources

MUMBAI SUBURBAN

Health

Last updated on 26 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Mumbai Suburban’s healthcare landscape, like that of many other regions in India, is shaped by the coexistence of indigenous practices and modern Western medical systems. For centuries, traditional healers, hakims, vaidyas, and folk practitioners, formed the foundation of local healthcare, using their knowledge of local plants and remedies to treat common illnesses.

The district’s formal healthcare system began to take shape under British rule. Unlike Mumbai city’s large colonial hospitals, the suburban belt saw the gradual spread of grant-in-aid dispensaries established in smaller localities. These early institutions laid the groundwork for the layered public health network that continues to serve the area today. Over time, as industrial growth and population density increased, new hospitals and private clinics emerged to meet the rising demand for healthcare services.

Healthcare Infrastructure

Mumbai Suburban’s healthcare infrastructure aligns with the broader Indian model, which is characterized by a multi-tiered system comprising both public and private sectors. Currently, the public healthcare system is tiered into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. Primary care is provided through Sub Centres and Primary Health Centres (PHCs), while secondary care is managed by Community Health Centres (CHCs) and Sub-District hospitals. Tertiary care, the highest level, includes Medical Colleges and District Hospitals. This system has been shaped and refined over time, influenced by national healthcare reforms.

The Three-Tiered Structure of the District

Mumbai Suburban’s organized healthcare system traces its roots to the colonial period, when early efforts laid the foundation for formal health services in what was then the extended periphery of Bombay. During the 19th century, as new settlements developed outside the city core, basic healthcare took shape through grant-in-aid dispensaries set up in localities such as Bandra and Kurla.

Bandra, at the time, was a growing settlement with a sizable East Indian and Koli community. In 1851, the Sir Kavasji Jehangir Dispensary was established here, funded by a prominent local zamindar and businessman whose contribution reflected the role of wealthy landholders in providing community services during British rule.

Kurla’s story, similarly, is rooted in earlier colonial transitions. Originally under Portuguese control through the 16th-century Treaty of Bassein, Kurla and its neighbouring villages were handed over to the British East India Company in 1808. That same year, the British granted Kurla to Hormasji Bamanji Wadia, an influential Parsi merchant, in exchange for land needed to expand the Apollo Pier in Bombay. This transfer coincided with the region’s rapid industrialisation. By the mid-19th century, Kurla had grown into a busy hub with mills, salt pans, and stone quarries that attracted migrant workers from within and beyond Bombay Presidency.

To meet the growing population’s health needs, Wadia is believed to have funded the Mithibai Hormasji Wadia Dispensary in 1855, donating £1,200—then a considerable sum—to establish what became one of the area’s early community health centres. Such local initiatives complemented the colonial government’s limited efforts, gradually expanding access to basic care for workers and their families.

By the mid-20th century, the district’s expanding population required larger facilities. In 1963, Bhagwati Hospital was founded in Borivali to serve the wider suburban population. Today it remains a key municipal hospital under the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), providing core specialties like orthopedics, pediatrics, and general surgery. Over the years, Bhagwati Hospital has played a frontline role during emergencies, from the 2005 floods to the 2011 train bombings and local building disasters.

![Bhagwati Hospital, Borivali[1]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/health/bhagwati-hospital-borivali1-2f048928.png)

The early 21st century has also seen the growth of superspeciality and multispecialty private hospitals in the district. Fortis Hospital Mulund, opened in 2002, is a major example. As part of Fortis Healthcare’s network of 28 hospitals across Asia, this 400-bed quaternary care facility is recognized as the first hospital in India and South Asia to achieve JCI accreditation—a standard it has retained multiple times. Fortis Hospital Mulund was also the first in India to gain NABH accreditation for Emergency Services and is noted for having one of the largest emergency rooms in Western Mumbai

![Fortis Hospital, Mulund[2]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/health/fortis-hospital-mulund2-216028ee.png)

Alongside these developments, the district has also seen a rise in Ayurvedic and homeopathy clinics, reflecting renewed local interest in traditional systems. Panchakarma clinics, for instance, are sought after for holistic treatments and notably locals remark that these options are not necessarily low-cost alternatives to allopathy. The costs for such services can sometimes match or exceed those of standard allopathic care.

However, similar to broader patterns that can be seen across India, the district’s healthcare infrastructure has developed unevenly across geographic lines. In particular, locals say regions like Govandi and Mankhurd experience underdeveloped healthcare infrastructure, highlighting disparities within the district.

Age-Old Practices & Remedies

While Mumbai Suburban is often associated with urban growth and industrialization, its forest-adjacent areas such as Aarey and the hamlets near Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP) remain pockets where traditional medicinal knowledge is still practiced. Communities like the Warli, Katkari, and Mahar Kolis, who have long inhabited these forested zones, continue to rely on locally sourced herbs and plants for everyday health needs. Living in close connection with the land, they forage and farm, preserving knowledge passed down through generations.

In an article by Purnima Sah (2024), Vanita Thakre, a resident of Warli Pada, demonstrates her community’s deep-rooted ethnomedicinal practices through ecological workshops. One example is the kon konsai kandh, a wild tuber found in the Aarey forests, valued not just as food but for its reputed effectiveness in managing diabetes. Likewise, jungli ambadi is widely used for relief from seasonal colds and coughs. Local knowledge systems also guide when certain plants should be consumed — for instance, kurdu, a plant with pink and white flowers, is believed to offer the best therapeutic benefits during the monsoon when its stem, seeds, and leaves are at their peak potency.

Major Epidemics and Outbreaks in the District

The Bombay Plague

Mumbai Suburban, like the city of Mumbai itself, has witnessed major public health challenges over time. One of the most severe was the infamous bubonic plague outbreak that gripped Bombay from 1896 for well over a decade. This event is vividly described in the 1915 novel Pootli: A Story of Life in Bombay by Ardeshir F. J. Chinoy and Mrs. Dinbai A. F. Chinoy, which opens with a depiction of its impact on “Bandora,” known today as Bandra.

Historical accounts, including reports by The Quint (2023), note that Ranwar village in Bandra — home to Goan, East Indian, Mangalorean, and Anglo-Indian communities — became an isolation zone for those infected. To combat the crisis, the British set up the Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT) to decongest crowded living quarters and improve sanitation. Churches like Mount Mary in Bandra reportedly suspended mass several times to prevent large indoor gatherings and curb the spread of infection, while local nuns and priests provided care to the sick.

In a related episode, Pandita Ramabai Saraswati’s writings provide rare insight into local perceptions and experiences under colonial medical control during this time. Her 1897 letter to the Bombay Guardian, later read in the British Parliament, criticized the treatment of women at plague segregation camps. She wrote, “the shameful way in which women were made to submit to treatment by male doctors goes to prove that English authorities in general do not believe that Indian women are honest and need special consideration… How would an Englishwoman, poor though she may be, like to be exposed to the public gaze and roughly handled by male doctors?”

COVID 19

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic brought new challenges to the district’s public health system. In Mulund West, for instance, a dedicated COVID-19 health center was set up in the former Richardson & Cruddas industrial facility to serve as a quarantine site for positive cases.

Sanitation | Cleanliness & Public Toilets

Toilets in urban India, including Mumbai, often struggle with sanitation issues despite being accessible. Recognizing the importance of improving facilities for women, the Central Railways launched the “Woloo Women’s Powder Room.” This initiative aims to provide healthier and safer sanitation options at railway stations, where many women commuters rely on the rail network for daily travel.

![Woloo Powder Room[3]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/health/woloo-powder-room3-f88a92f3.png)

Women in Mumbai depend heavily on trains for commuting, making access to clean and safe restrooms essential for their comfort and dignity. Launched in 2023, the Woloo facility offers services for Rs 10 per use, with annual subscriptions available for frequent travelers. A mobile app-based model at just Rs 1 per day allows unlimited access to any Woloo toilet nationwide. Currently, these facilities can be found near Mulund, Ghatkopar, and Kanjurmarg Stations.

Graphs

Healthcare Facilities and Services

Morbidity and Mortality

Maternal and Newborn Health

Family Planning

Immunization

Nutrition

Sources

Aditi Suryavanshi. 2023. "In Photos: Christmas in the Lanes of Ranwar Village in Bandra." The Quint, India.https://www.thequint.com/photos/in-photos-ch…

B. Arunachalam, et al. 1986-87. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Greater Bombay District. Vol. I, II, III. Gazetteers Department, Govt of Maharashtra. Mumbai.

Fortis Healthcare. "Fortis Hospital." Fortis Healthcare.https://www.fortishealthcare.com/location/fo…

Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency.1882 (Revised 1982). Thana District. Parts I and II. Superintendent of Government Printing, Bombay.

Kamal Mishra. 2023. "Mumbai: Central Railway Introduces Woloo Women’s Powder Room at Mulund Station." The Free Press Journal.https://www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai/mumba…

M Choksi, B. Patil et al. 2016. Health systems in India. Vol 36 (Suppl 3). Journal of Perinatology.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC514…

Mumbai Story. 2016. "Kurla Village, Part 1: The Suburb Gets Its Name from the East Indian Village of Kurla." Facebook Post.https://www.facebook.com/mumbaioldstories/po…

Murali Ranganathan. 2020. How the first English novels by Parsis were written in the backdrop of the plague and politics. Dawn.https://www.dawn.com/news/1569130

National Health Mission (NHM). "About Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA)." National Health Mission, India.https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1…

Purnima Sah. 2024. How to forage for lunch in Mumbai’s Aarey forest. The Hindu.https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/…

S. M. Edwardes, et al. 1909. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Bombay City and Island. Vol. I, II, III. Bombay.

Shashi Prabhu & Associates. "Bhagwati Hospital." Shashi Prabhu & Associates.https://www.shashiprabhu.com/work/healthcare…

Susie Tharu, and Lalita, eds. 1991. Women Writing in India, Volume I: 600 BC to the Early Twentieth Century. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Last updated on 26 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.