Contents

- Malabar Hill

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Flora and Fauna

- Forest Reserves

- Joseph Baptista Gardens

- Hanging Gardens (Pherozeshah Mehta Gardens)

- Horniman Circle Gardens

- Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan and Zoo (Rani Bagh)

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Air Pollution

- Marine Pollution

- Waste Management

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Coastal road project

- C40 Cities

- Farming Practices Along the Tracks

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- Human Footprint

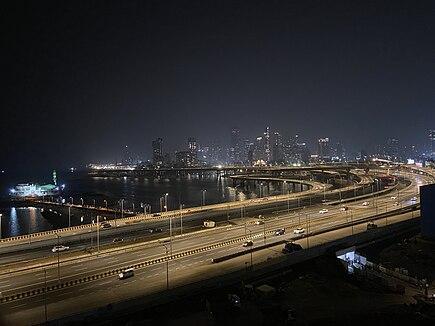

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

MUMBAI

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

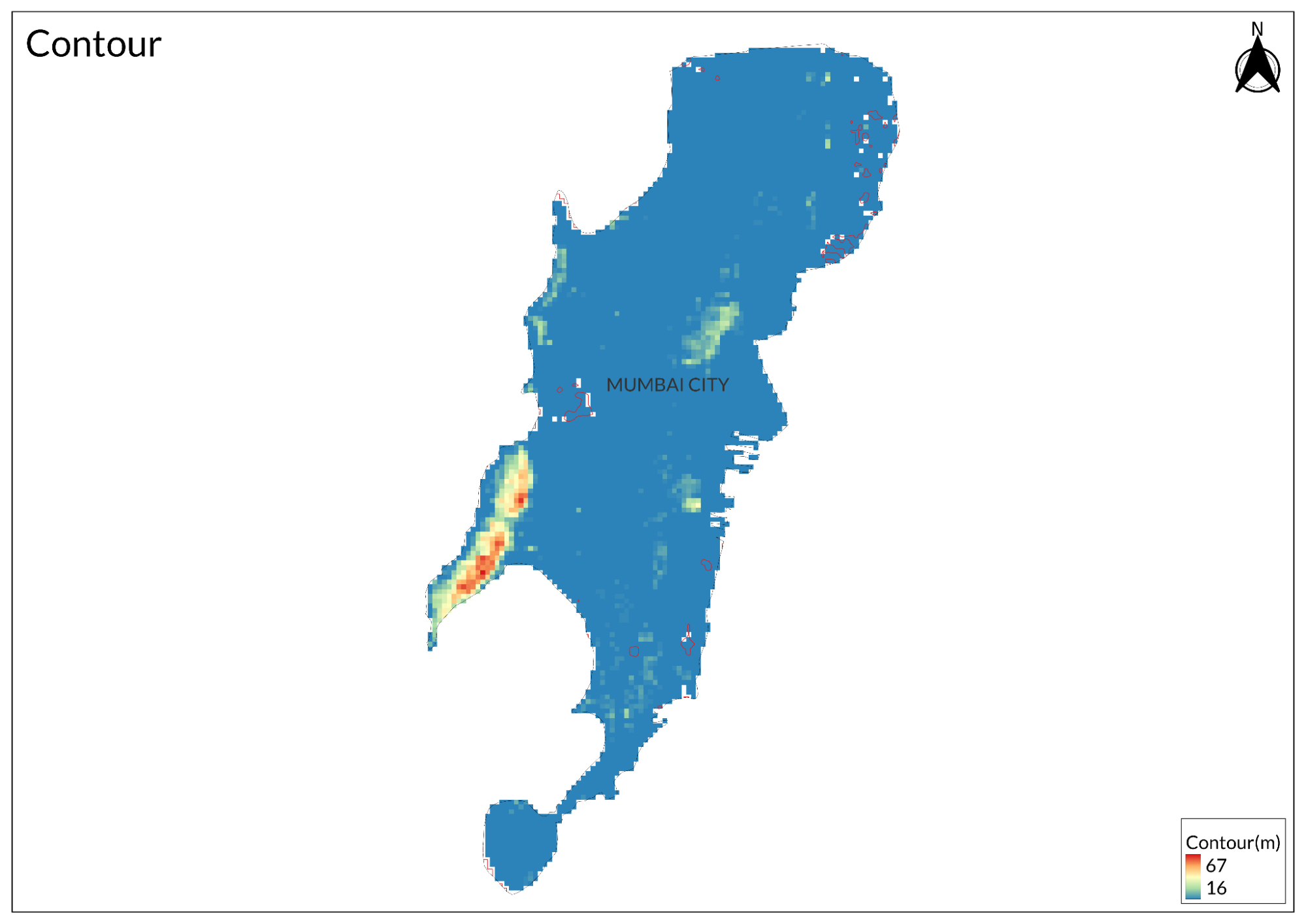

Originally a group of seven islands, the city has been extensively reclaimed and now boasts coastal plains, hills, and a deep natural harbor along the Arabian Sea. The city's topography varies significantly. The northern region is hilly, with elevations reaching up to 450 meters (1,480 feet) in areas like Powai. In contrast, the southern part is low-lying and densely populated. Covering about 468 square kilometers (169 square miles), Mumbai features notable hills such as Ghatkopar and Trombay, as well as several lakes like Tulsi and Powai.

Malabar Hill

The Great Fire of 1803 devastated much of the city within the old fort walls, prompting British administrators to encourage residents to build homes outside the fort. This led to early development around Malabar Hill, and by 1826, the population had grown to over 2,000, comprising English, Portuguese, Parsis, and Hindus. The construction of the first access road to Malabar Point in 1828 marked a significant step towards its urbanization.

As the walls of Bombay Fort were demolished in 1864, the elite began moving to Malabar Hill, transforming it into a desirable residential area. By the 1870s, it had become known for large estates similar to those in Mahabaleshwar. However, from the 1970s onwards, the character of Malabar Hill shifted dramatically as skyscrapers replaced garden bungalows, increasing population density and altering its landscape.

Today, Malabar Hill is recognized as one of Mumbai's most affluent neighborhoods, home to numerous business tycoons and film personalities

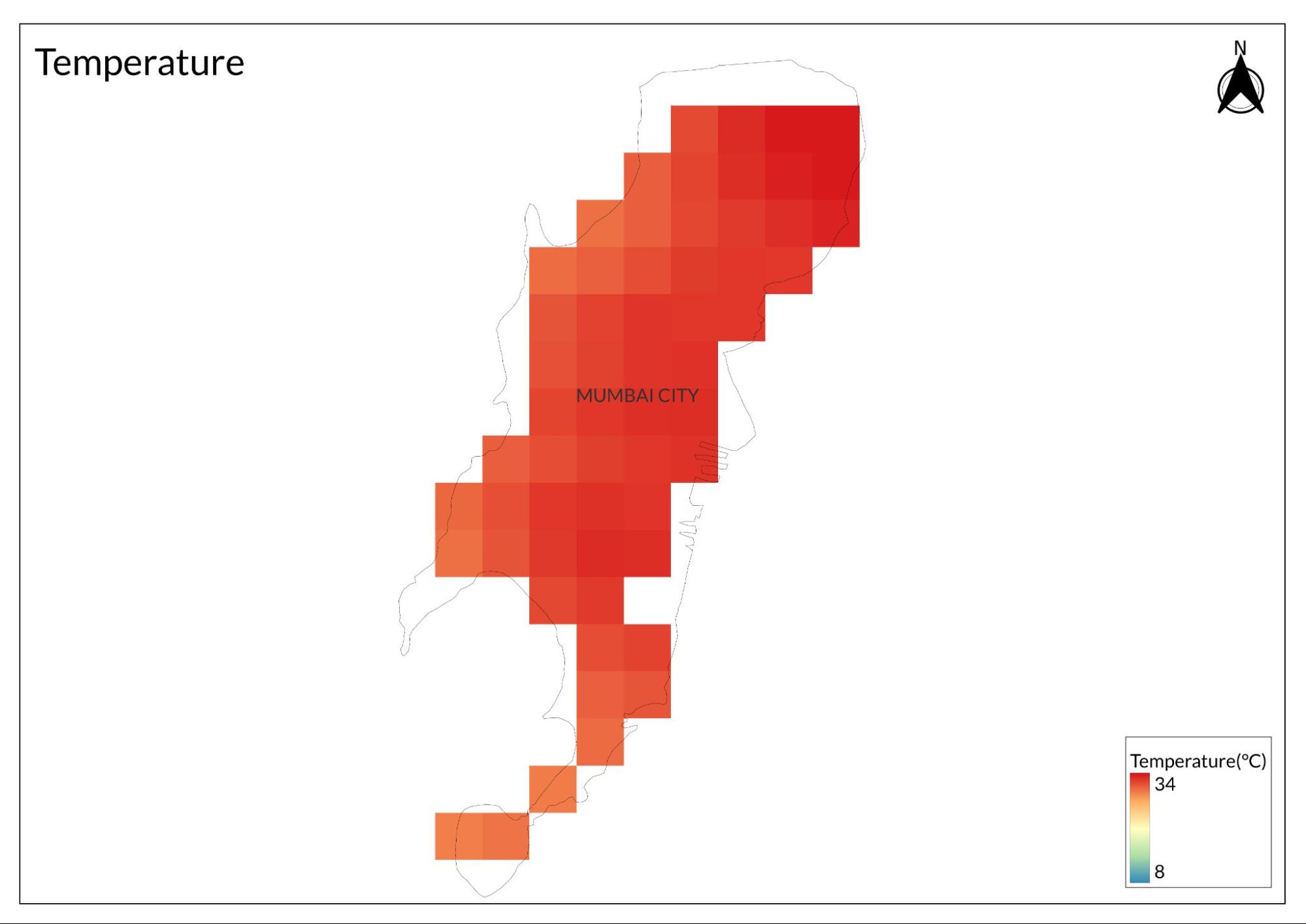

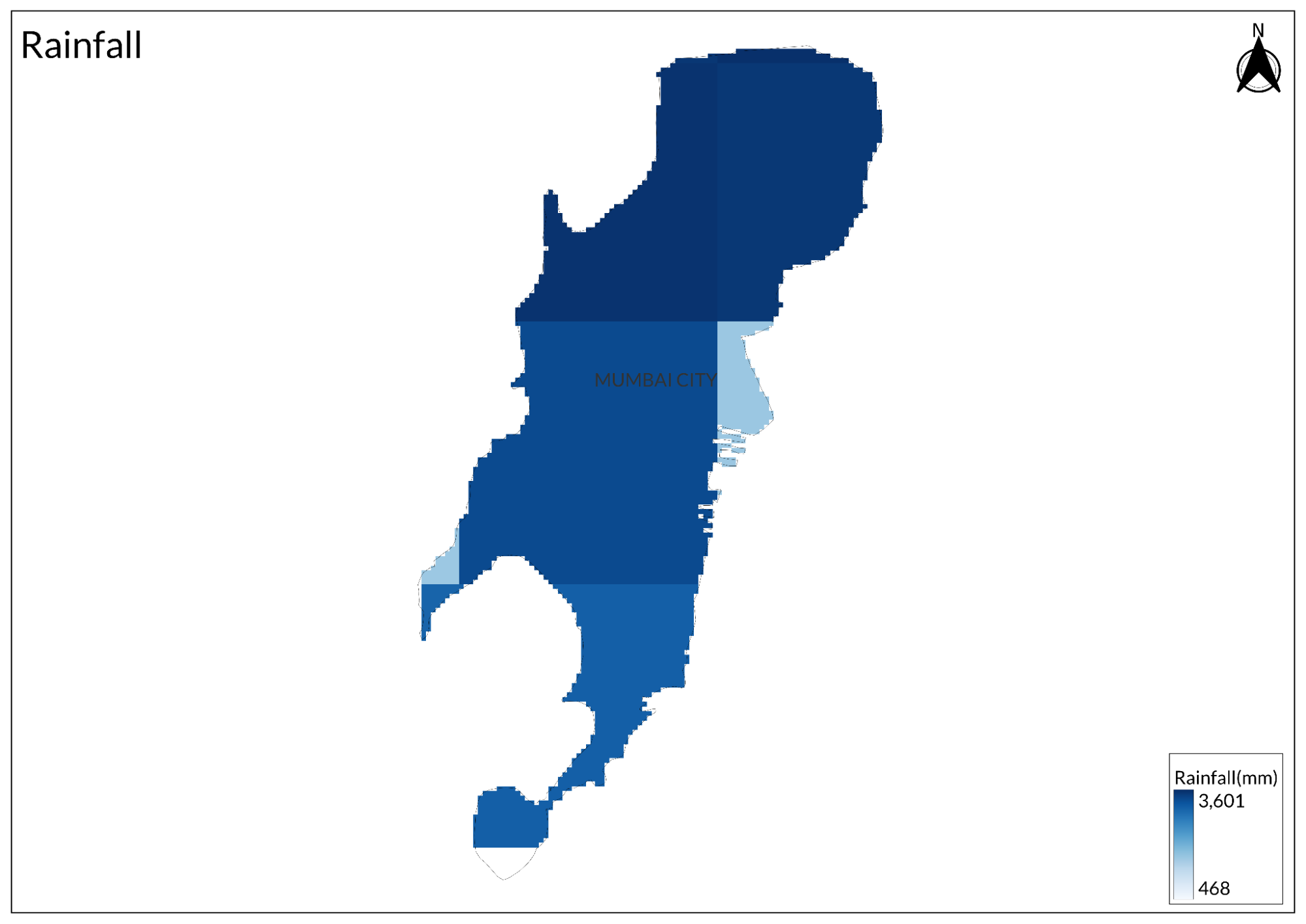

Climate

Mumbai experiences a tropical climate marked by high humidity and elevated temperatures throughout the year, divided into three distinct seasons that significantly influence its weather patterns. Summer, from March to June, sees temperatures soaring to around 35°C (95°F), characterized by intense heat and humidity that make outdoor activities challenging during peak hours. Following this, the monsoon season spans from June to September, bringing heavy rainfall with an average annual precipitation of approximately 2,000 mm (78 inches). This period is vital for replenishing the city's water resources but also leads to flooding and other challenges due to inadequate drainage systems. Finally, winter lasts from October to February, offering cooler and more pleasant weather with temperatures ranging from 15°C to 25°C (59°F to 77°F), making it the most comfortable season for both residents and visitors.

Historically, Mumbai received an average of about 94 inches of rain annually, primarily during the four-month monsoon season. Traditionally, residents prepared for the monsoon by clearing drains and repairing roofs; however, changing rainfall patterns have led to critical issues. Severe flooding, which once occurred infrequently, is now a near-annual event due to an increase in cyclone frequency and intensity. From 2001 to 2019, there was a 52% rise in cyclone occurrences and a 150% increase in very severe storms, with cyclone durations increasing by 80%. This trend exacerbates the city's vulnerability to flooding.

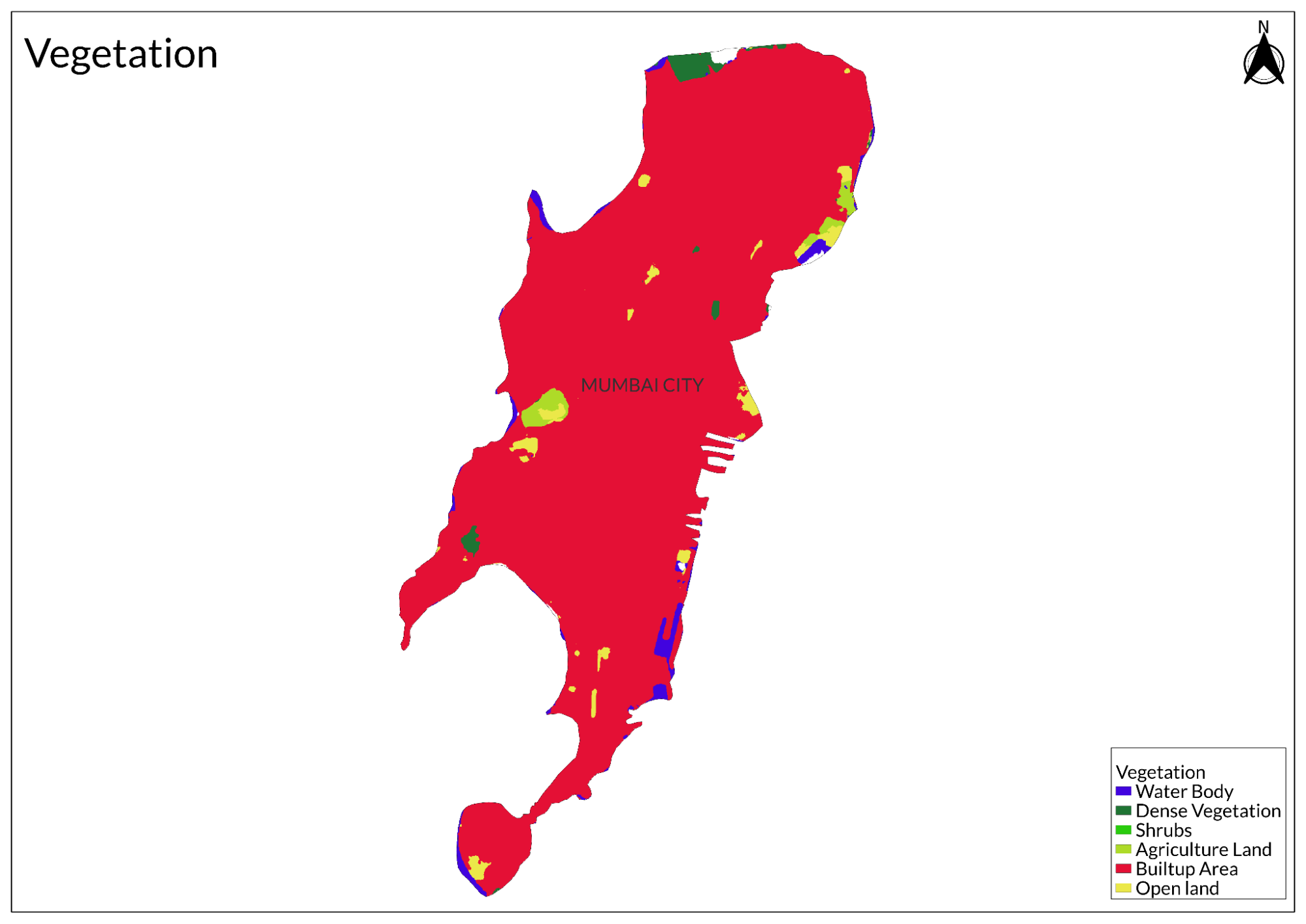

Rapid urbanization has significantly impacted Mumbai's landscape, resulting in a loss of 58% of its already limited open space between 1991 and 2018. This urban sprawl over floodplains and hills heightens the risk of severe flooding during extreme rainfall events. The city’s infrastructure struggles to manage the volume of water, leading to disruptions in train services, increased water-borne diseases, and occasional landslides or building collapses.

The increasing number of cyclones in the Arabian Sea and rising sea levels further complicate the situation. Cyclones can drive storm surges that flood coastal areas; for instance, Cyclone Tauktae in 2021 brought record rainfall for May. Instead of consistent rain, Mumbai now experiences more days of heavy rainfall (over 2.5 inches in 24 hours) interspersed with long dry periods—an erratic pattern attributed to increased atmospheric moisture from a warming Arabian Sea. Extreme precipitation events have tripled from 1950 to 2015 across western India, resulting in flash floods and landslides.

Local scientists suggest that clusters of concrete structures contribute to warmer temperatures and atmospheric instability, potentially intensifying monsoon rainfall. Additionally, the monsoon season now ends later than before, requiring extended vigilance from residents. The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) classifies rainfall intensity and issues color-coded warnings; however, Mumbai's infrastructure often fails to handle sudden heavy downpours effectively.

Projections indicate a potential increase in rainy days by 3-12% in Mumbai city and by 3-9% in the suburbs by 2050, depending on carbon emission trends. This increase poses significant challenges for the city when combined with other climate change effects such as rising temperatures and sea levels.

Geology

Mumbai's geology is primarily characterized by its volcanic origins, particularly the Deccan Trap formation, which consists of extensive basalt lava flows. These flows were formed between 68 and 60 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous to Early Paleocene periods. The region's geological history reflects a complex interplay of volcanic activity and sedimentation, resulting in a unique geological framework that distinguishes it from other areas in the Deccan Volcanic Province.

The predominant rock type in Mumbai is basalt, an igneous rock rich in iron, magnesium, and calcium silicate minerals. In addition to basalt, the region features other volcanic rocks such as rhyolites and trachytes, which are more silica-rich and contain minerals like quartz. Much of the volcanic activity occurred underwater, leading to the formation of distinctive structures such as pillow lavas and hyaloclastites, which differ from the predominantly subaerial volcanism seen in other parts of the Deccan.

Structurally, the lava flows in Mumbai exhibit a pronounced westward tilt known as the Panvel Flexure. This tilt likely resulted from crustal bending due to cooling and sediment weight or from movement along west-facing faults formed during continental breakup.

Mumbai is also located in a seismically active zone classified as Seismic Zone III, indicating potential earthquakes of up to magnitude 6.5. The area is intersected by 23 fault lines, adding to its geological intricacies.

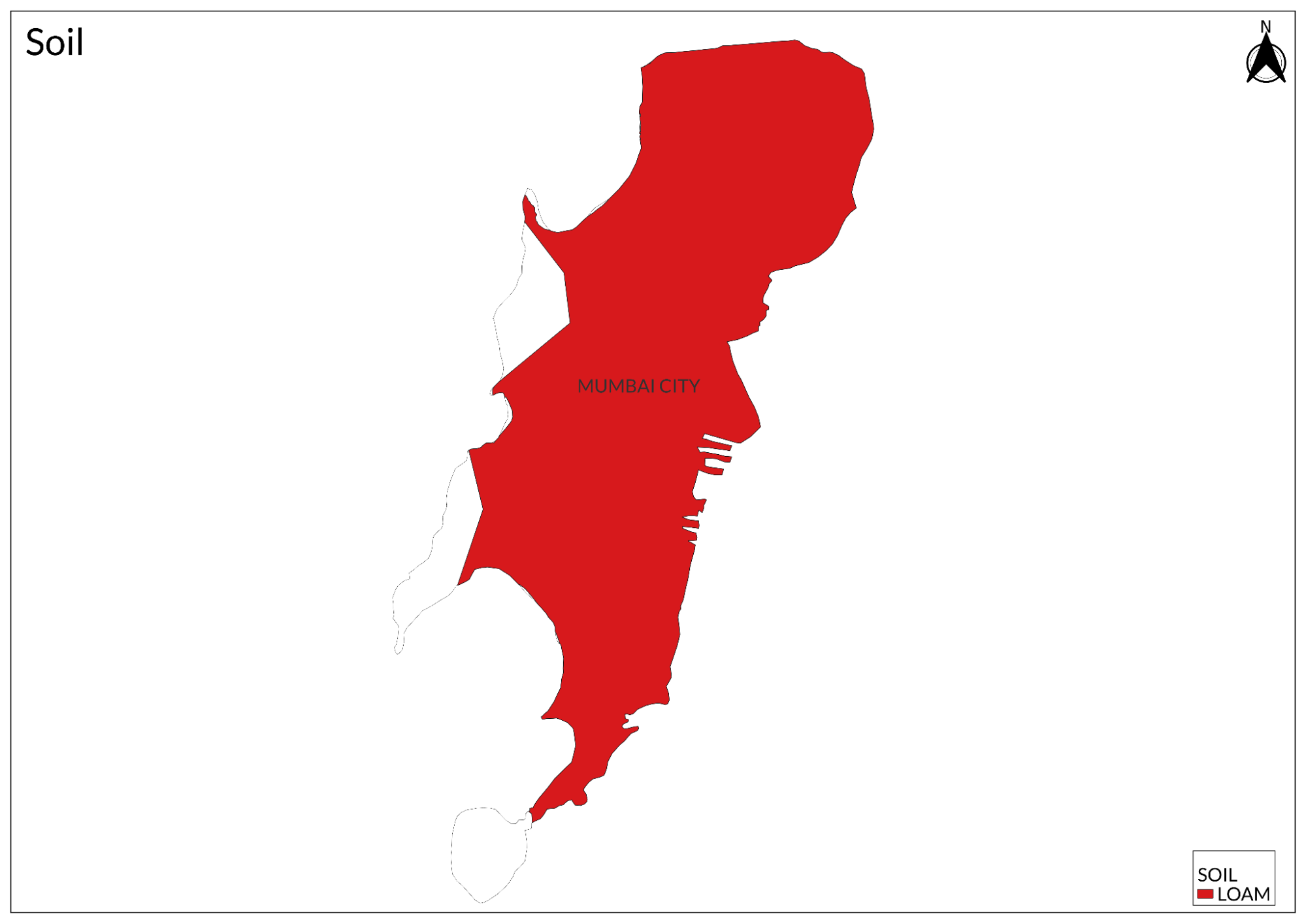

Soil

The soil cover in Mumbai varies; sandy soils are prevalent near the coast, while alluvial and loamy soils dominate in the suburbs. The urbanization of Mumbai has significantly impacted geological outcrops, making many historical rock formations inaccessible.

Minerals

Maharashtra, including Mumbai, has substantial mineral reserves that contribute significantly to the state's economy. The state is known for its diverse mineral resources, which include approximately 5.5 billion tonnes of coal, about 1.37 billion tonnes of limestone, around 20 million tonnes of manganese ore, and approximately 260 million tonnes of iron ore. While Mumbai itself may not be as mineral-rich as other regions in India, the geological features of the area provide valuable resources that support local industries.

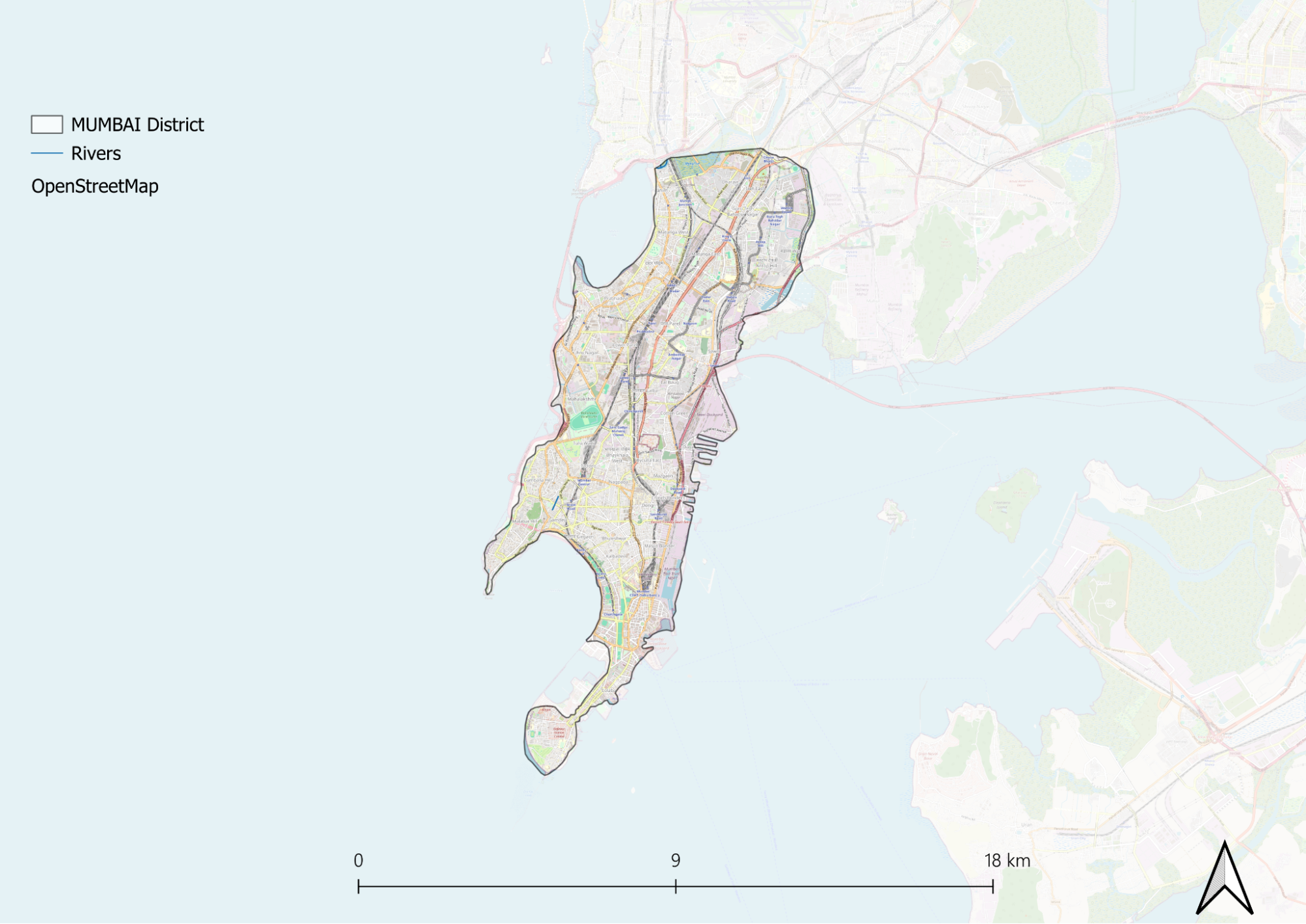

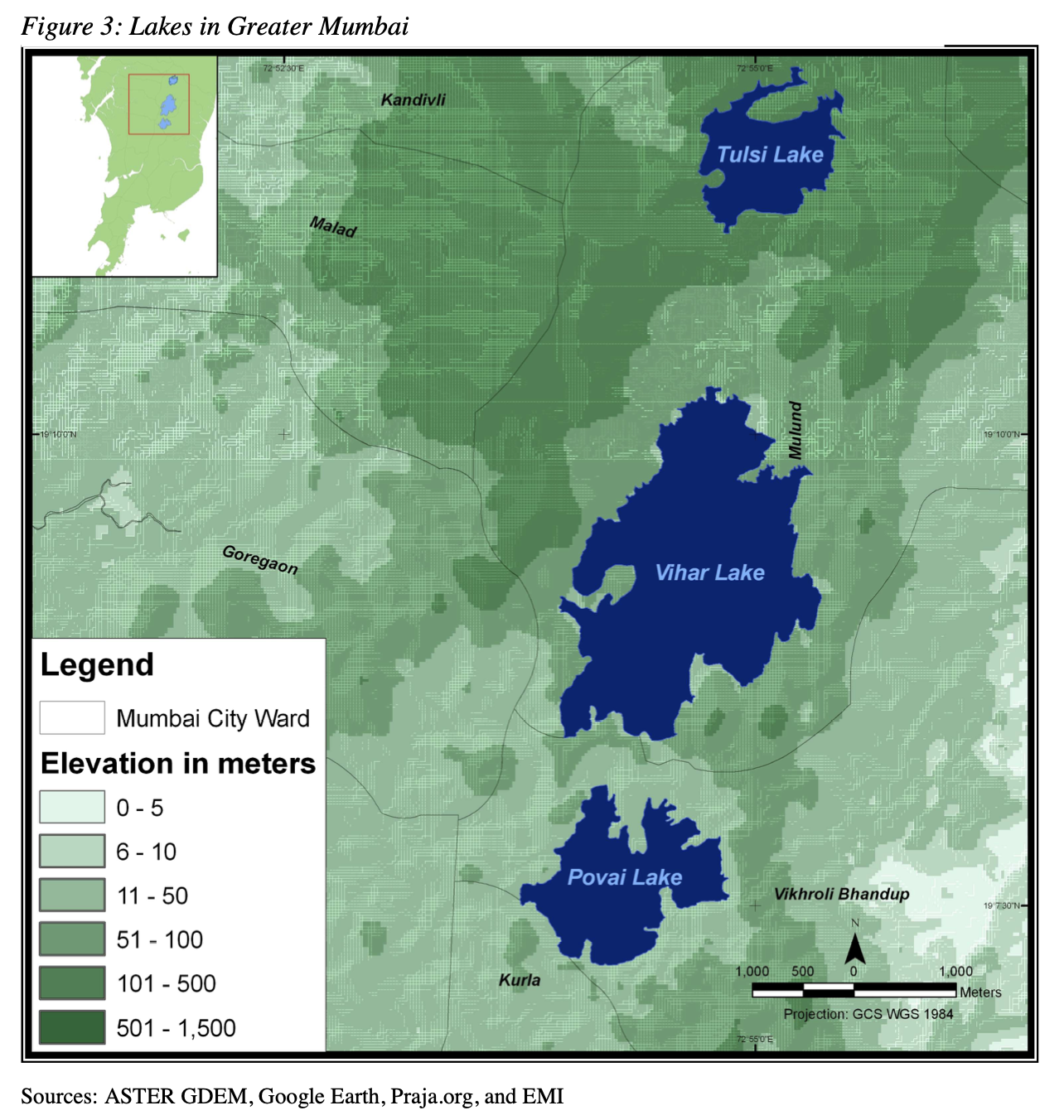

Rivers

Mumbai features several important bodies of water, including lakes and rivers that are vital for the city's water supply and ecology. Within the metropolitan area, three key lakes are Tulsi Lake, Vihar Lake, and Powai Lake. Tulsi Lake, located in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, is the second-largest freshwater lake in Mumbai and serves as a significant drinking water source. Vihar Lake, built in 1860, also contributes to the city's water supply. Powai Lake, an artificial lake created in 1891, is surrounded by residential areas and is known for its biodiversity.

In addition to these lakes, Mumbai relies on Lower Vaitarna, Upper Vaitarna, and Tansa Lake for water. The city has three small rivers: Dahisar River, Poisar River, and Oshiwara River, which all originate in the national park. The Mithi River, originating from Tulsi Lake, is heavily polluted as it collects overflow from Tulsi and Vihar Lakes.

Mumbai's coastline includes numerous creeks and bays stretching from Thane Creek in the east to Madh Marve in the west. The eastern coast of Salsette Island features extensive mangrove swamps rich in biodiversity, while the western coast is mostly sandy and rocky. These bodies of water are crucial for both the city's inhabitants and its ecological health.

Flora and Fauna

A Nagpur-based wildlife cartoonist, Rohan Chakravarty, has created a unique map for Mumbai that showcases the city's surprising biodiversity. This initiative is part of a campaign by the Ministry of Mumbai's Magic, a collective focused on climate action, which includes local residents, environmental organizations like Waatavaran, and the entertainment company DeadAnt. Their goal is to harness community power to protect Mumbai's natural heritage.

The interactive biodiversity map not only highlights various flora and fauna but also features two indigenous communities: the Warli people and the Koli, one of the city's oldest fishing communities. It includes special sections that identify hidden wildlife hotspots throughout the city. The map serves as an educational tool, aiming to raise awareness about Mumbai's rich biodiversity and inspire residents to engage in conservation efforts.

Originally launched in 2020 as a static map, the updated interactive version allows users to click on different species to learn more about their habitats and conservation status. The map covers the Mumbai Metropolitan Region and important water bodies such as the Arabian Sea and Thane Creek, showcasing 78 species of fauna and 17 species of flora.

Chakravarty emphasizes that making the map interactive significantly broadens its reach, especially among younger audiences who are more likely to engage with digital content. By fostering a sense of ownership among Mumbaikars regarding their city's biodiversity, this project aims to encourage proactive conservation efforts.

For more details about the map and its features, you can explore it through the Ministry of Mumbai's Magic website or view the specific biodiversity resources linked in their campaign.

Forest Reserves

Mumbai has several significant gardens that serve as essential green spaces amid urban growth.

Joseph Baptista Gardens

These were originally part of Mazagon Fort from the 1660s and became a public garden after serving as a water reservoir since 1884. The gardens offer a blend of historical significance and natural beauty.

Hanging Gardens (Pherozeshah Mehta Gardens)

These were built in 1881 on Malabar Hill. These terraced gardens provide stunning views of the Arabian Sea and the Mumbai skyline. They are known for unique hedges shaped like animals and are popular with both locals and tourists.

Horniman Circle Gardens

These are located in Mumbai's Fort area, surrounded by historical buildings.

Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan and Zoo (Rani Bagh)

It was established in 1861 in Byculla. This botanical garden spans over 60 acres and includes a zoo, featuring more than 4,213 trees across 256 species. It attracts an average of 8,000 visitors daily, with numbers surging to 40,000 on holidays. A dedicated group of five women has worked for years to protect Rani Bagh from redevelopment threats.

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Air Pollution

Mumbai is grappling with a severe air pollution crisis, exacerbated by its industrial activities and heavy reliance on fossil fuels. The city’s air quality has deteriorated significantly over recent years, with a report indicating a 22% decline between 2019 and 2023. This decline has led to a staggering 305% increase in air pollution complaints, highlighting growing public concern about the health impacts associated with toxic particulate matter. Studies have shown that the concentration of harmful PM2.5 particles in Mumbai is alarmingly high, often surpassing levels found in other major cities, including Delhi.

The primary sources of air pollution in Mumbai include traffic emissions, construction activities, and waste management practices. Road traffic accounts for approximately 80% of the city's fossil fuel emissions, making it a significant contributor to poor air quality. Additionally, construction dust from rampant real estate development contributes over 71% of particulate matter in the air, a sharp increase from previous years. The city also faces challenges from open waste burning and emissions from landfills, which further compromise air quality.

Recent assessments have identified specific areas within Mumbai that consistently record the highest pollution levels, including Deonar, Govandi, and Trombay. These hotspots are critical for targeted interventions aimed at reducing pollution. The government is urged to implement stricter regulations on vehicle emissions and to promote cleaner fuels and electric vehicles as part of a comprehensive strategy to tackle the crisis.

Marine Pollution

Mumbai is facing a significant marine pollution crisis, primarily due to the inadequate treatment of sewage. The city generates between 2,200 and 2,400 million liters of sewage daily, but only about 1,500 million liters are treated at various sewage treatment plants (STPs). This leaves approximately 700-900 million liters of untreated sewage, which is either processed by private STPs or directly discharged into rivers, creeks, or the Arabian Sea. Consequently, around 25% of the city's waste, especially from slum areas that lack proper sewer connections, flows untreated into local water bodies.

The impact of this pollution is profound, affecting both marine life and public health. Untreated sewage not only degrades the habitat for marine species such as crabs, fish, and dolphins but also poses risks to humans who consume seafood from these waters. Environmental activists have raised alarms about the visibility of untreated waste in stormwater drains that eventually lead to the sea. Reports indicate that many of Mumbai's rivers have become mere conduits for sewage, with little to no fish remaining in their waters.

Inadequate infrastructure exacerbates the problem; many outfalls designed to manage sewage are either submerged during high tides or clogged with plastic and other debris. Of the 186 outfalls in Mumbai, only a small fraction is positioned above high tide levels, rendering them ineffective during flooding events. Major outfalls are responsible for discharging a mix of sewage and plastic waste directly into the sea.

To combat this issue, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has announced plans to construct seven new STPs at a cost of approximately ₹26,436 crore. These facilities aim to treat an additional 2,464 million liters of sewage daily, with half of it undergoing tertiary treatment for potential reuse in non-potable applications. However, completion timelines for these projects extend from four to six years.

Waste Management

Mumbai faces significant challenges related to its drainage and solid waste management systems, particularly during the monsoon season when heavy rains exacerbate flooding issues. Despite the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) investing substantial funds in desilting efforts, drains across the city remain clogged with solid waste, leading to persistent waterlogging in low-lying areas.

The city's drainage network, which dates back to colonial times, includes a complex system of stormwater drains and open canals. However, this infrastructure is often overwhelmed by the volume of waste dumped haphazardly into the drains. Although the BMC claims to have met its pre-monsoon desilting targets, many drains are still filled with debris, rendering them ineffective during heavy rainfall.

A visit to various nullahs revealed that solid waste—including plastics, medical waste, and construction debris—fills these drainage channels, obstructing water flow. Residents report that despite regular desilting efforts, the drains quickly become clogged again due to ongoing dumping practices. Encroachments along drain banks further complicate maintenance efforts, as access for cleaning vehicles is often restricted.

In response to these challenges, the BMC is exploring long-term solutions such as converting open drains into covered box drains to improve their capacity and reduce waste entry. Additionally, there are plans to implement daily waste collection from drains and install nets to catch floating debris.

Experts emphasize the need for a comprehensive sewage network in Mumbai to address the unchecked dumping of waste by various sources, including slums and small industries. They argue that a proactive approach involving proper waste segregation and treatment is essential for sustainable drainage management.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Coastal road project

The Mumbai Coastal Road Project (MCRP) aims to connect Marine Drive with the Bandra Worli Sea Link (BWSL), with its foundation stone laid in December 2018. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) is managing the project's implementation, with AECOM serving as the general consultant.

A key feature of the project is the 2.07-km-long twin tunnels starting in Girgaum and running 7 to 20 meters beneath the Arabian Sea. Phase 1 is estimated to cost Rs 12,700 crore. By the end of 2023, the BMC awarded contracts for the second phase of the MCRP to four infrastructure firms. The project is designed to link Versova in the western suburbs to Dahisar in northern Mumbai and is divided into six segments (A, B, C, D, E, and F).

Phase 2 includes a 4.5 km stretch from Versova to Bangur Nagar (Goregaon) for Package A, a 1.66 km stretch from Bangur Nagar to Mindspace (Malad) for Package B, and both north and south-bound carriageways covering 3.66 km each for Packages C and D, connecting Mindspace to Charkop (Kandivali). Additionally, Package E involves a 3.78 km link between Charkop and Gorai, while Package F covers a 3.69 km stretch from Gorai to Dahisar. The contracts were awarded to:

- APCO Infratech for packages A and F.

- J Kumar Infra projects (in a joint venture with NCC Limited) for package B.

- Megha Engineering Private Limited for packages C and D.

- Larsen and Toubro (L&T) for package E.

- The estimated cost of Phase 2 is Rs 18,000 crore.

The Coastal Road Project has faced significant criticism due to various issues.

Firstly, it is considered an inefficient mode of transportation. Car-based transport is inherently inefficient as it accounts for only a small percentage of daily trips. This inefficiency highlights skewed public investment priorities. Car ownership has been increasing rapidly, growing by 9.8% annually between 2014 and 2018. This rise in car reliance has led to greater fuel consumption and vehicular pollution. For over two decades, the city's investments have largely favored car-oriented infrastructure and, more recently, Metro rail, while public bus and suburban rail systems have been neglected and underfunded.

Moreover, the project is likely to exacerbate the class divide. The southern and western parts of Mumbai are already well-served, whereas the rest of the city, with some exceptions, remains poorly serviced. The Coastal Road Project reinforces this south-north spatial structure and fails to connect the western part to the central and eastern regions. Consequently, it primarily benefits car owners living along the well-served western corridor, offering little to the rest of the city. Ultimately, the Coastal Road Project is seen as a product of a flawed planning system that sacrifices the basic needs of the many to provide luxuries for a few.

The Koli community of Worli has staged major protests, fearing that the Coastal Road Project will devastate their livelihood. The fisherfolk, who operate in shallow waters which are prime fishing areas, claim that sea reclamation is already affecting their catch. They warn that the construction of new pillars will further obstruct their navigation routes, making fishing nearly impossible. During storms or rough seas, the boats risk crashing into these pillars. They note that the existing Sea Link pillars have already slowed them down, and additional pillars will only worsen the situation, ultimately destroying their livelihood.

Unlike the Save Aarey movement, the Coastal Road Project has not seen a unified city-wide protest. Smaller citizen groups only began protesting in early 2019, after the initial 10 km of reclamation work was well underway.

One reason for the lack of widespread support is that forest conservation and tree protection are more straightforward and widely understood concepts. Even school children are taught about the importance of saving trees, which contribute to clean air. In contrast, the significance of coastal ecology, marine life, and tidal buffer zones is not as well known. Additionally, the Aarey protesters had alternative options to negotiate, whereas the Coastal Road debate is limited to whether the road should be built as a sea link or through reclamation, offering little room for compromise.

C40 Cities

Mumbai secured a place in the C40 cities, on tackling climate change and driving urban action that reduces greenhouse gas emissions and climate risks, while increasing the health well-being and economic opportunities of urban citizens. The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group is a group of 97 cities around the world that represents one-twelfth of the world's population and one-quarter of the global economy.

Being a part of C40 can make a huge difference for Mumbai. Many C40 cities, including Auckland, Berlin, Lima, Rome, Paris, and Mexico City opened or improved over 1,000 km of temporary or extended bike lanes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing safe walking and cycling and reducing pressure on public transportation, particularly for critical staff. The same can be done in Mumbai to tackle air pollution and mobility issues.

As a financial centre, Mumbai's economy is skewed towards service sectors and high-tech manufacturing, rather than heavy industry and agriculture. The majority of goods consumed by residents are often imported. If C40 mayors can influence patterns of consumption to be less carbon-intensive, they can have a significant impact on the economy outside their city.

Apart from being a C40 city, the city also has a Maharashtra-wide climate policy called Majhi Vasundhra. Majhi Vasundhara focuses on restoring the five elements of nature through six initiatives. The Environment and Climate Change Department, Govt. of Maharashtra, targeted these initiatives to engage stakeholders from different sectors and age groups to sensitize them about sustainable development and climate change. Majhi Vasundhara works with Maharashtra's local governments to define new action points for environmental improvement. It aims to establish connections with government agencies, local and global corporate bodies and put both national and international non-profit organisations under one umbrella to pioneer change.

Farming Practices Along the Tracks

Farmers like Ramkishore Chauhan have been growing crops between Elphinstone Road and Lower Parel stations for over 25 years. They cultivate a variety of vegetables, including fenugreek, spinach, and radish, benefiting from the fertile soil and monthly harvests. Despite lacking electricity for irrigation, farmers use diesel pumps to draw water from nearby drains. During monsoon floods, they adapt by planting taller crops like lady's finger.

Farmers are aware of their precarious situation; they understand that they could be asked to vacate the land at any time by railway authorities. Jitendra Chauhan, another farmer, notes that shopkeepers often buy directly from them, eliminating the need for market trips.

Many farmers live in makeshift huts without basic amenities like electricity. Ramkripan, who moved from Jaunpur with his family, emphasizes the importance of family support despite the harsh living conditions. He also raises poultry alongside his vegetable farming.

Farmers rely on dung as fertilizer, procuring it from local dairy farms such as Aarey milk colony. However, challenges arise due to infrastructure changes, such as a wall that restricts access to manure deliveries. Kanta Yadav, a long-time farmer in the area, faced fines due to these logistical issues.

The Central Railways initiated the "Grow More Food" scheme to utilize unused land and prevent slum encroachment. Under this program, railway employees were allocated land on lease for farming, generating additional income for them while allowing the railways to earn revenue from the land. The lease rates have increased over time but remain nominal compared to market prices.

Despite concerns about using untreated water for irrigation, tests conducted by accredited laboratories confirmed that vegetables grown along railway tracks are safe for consumption. This initiative highlights how urban spaces can be repurposed for agriculture, contributing to food security in densely populated areas like Mumbai.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Acharya, P. 2023, June 28.The muck stops here: As solid waste chokes Mumbai drains, is desilting enough? The Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mum…

Bavadam, L. 2022, September 8. 160 years of mumbai’s rani bagh. Frontline.https://frontline.thehindu.com/environment/c…

Bharucha, N. K. 2022, October 2.25% of Mumbai sewage flows untreated into sea. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/25-of-mu…

Chakravarty, R. Biodiversity map. Ministry of Mumbai’s Magic.https://ministryofmumbaismagic.com/biodivers…

Chandrashekhar, V 2022, February 7. Climate change is stretching mumbai to its limit. The Atlantic.https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/…

City Profile of Greater Mumbai. 2011. Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai.https://dm.mcgm.gov.in/assets/pdf/city_profi…

Mehta, S. 2023, April 22. Five female senior citizens have joined forces to preserve Mumbai’s largest green space. Vogue India.https://www.vogue.in/content/rani-bagh-is-fa…

Mukherjee, S., & Chaillat, K. 2013, February 11. Mumbai’s urban railway farms. Down To Earth.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/m…

Nair, M. R. 2013, November 21. Malabar Hill: How a jungle turned into a posh address. DNA India.https://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-malab…

Nambiar, S. 2016, August 31. The history of the hanging gardens of mumbai in minute. Culture Trip.https://theculturetrip.com/asia/india/articl…

Rahaman, S., Jahangir, S., Haque, M. S., Chen, R., & Kumar, P. 2021. Spatio-temporal changes of green spaces and their impact on urban environment of Mumbai, India.Environment, Development and Sustainability,23(4), 6481–6501.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00882-z

Sethna, S. F. 1999. Geology of mumbai and surrounding areas and its position in the deccan volcanic stratigraphy, india. Journal of Geological Society of India, 359–365.https://www.geosocindia.org/index.php/jgsi/a…

Shahfahad, Rihan, M., Naikoo, M. W., Ali, M. A., Usmani, T. M., & Rahman, A. 2021. Urban heat island dynamics in response to land-use/land-cover change in the coastal city of mumbai.Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing,49(9), 2227–2247.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12524-021-01394-7

Virani, S. 2022, June 4.Climate change, rainfall patterns and what it means for Mumbai’s monsoon. Citizen Matters.https://citizenmatters.in/mumbai-monsoon-cli…

Warang, R. (2021, May 30). What does becoming a C40 city mean for Mumbai? Talk Dharti To Me.https://www.talkdhartitome.com/post/what-doe…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.