Contents

- History

- Ancient Trade Routes & Centers

- TraditionalMeans of Conveyance

- Modes of Transportation in the District

- Train and Rail Systems

- Cycling Infrastructure

- Overview of Bus Networks

- Metro Services

- Autos & Shared Vehicles

- Cars & Two-Wheelers

- Air Travel

- Ferries & Water Transport

- Traffic Map & Congestion

- Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)System

- AttitudeTraffic Rules & Regulations

- Communication Networks

- Newspapers & Magazines

- What’s on the Billboards? A Look at Pune’s Hoardings

- Graphs

- Road Safety and Violations

- A. Cases of Road Safety Violations

- B. Fines Collected from Road Safety Violations

- C. Vehicles involved in Road Accidents

- D. Age Groups of People Involved in Road Accidents

- E. Reported Road Accidents

- F. Type of Road Accidents

- G. Reported Injuries and Fatalities due to Road Accidents

- H. Injuries and Deaths by Type of Road

- I. Reported Road Accidents by Month

- J. Injuries and Deaths from Road Accidents (Time of Day)

- Transport Infrastructure

- A. Household Access to Transportation Assets

- B. Length of Roads

- C. Material of Roads

- Bus Transport

- A. Number of Buses

- B. Number of Bus Routes

- C. Length of Bus Routes

- D. Average Length of Bus Routes

- E. Daily Average Number of Passengers on Buses

- F. Revenue from Transportation

- G. Average Earnings per Passenger

- Communication and Media

- A. Household Access to Communication Assets

- B. Newspaper and Magazines Published

- C. Composition of Publication Frequencies

- Sources

PUNE

Transport & Communication

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

In the Pune district, historically, its location on the Deccan plateau placed it along inland trade routes connecting coastal ports with markets in the interior. This older network included passes like Naneghat, which linked traders from the Konkan to the plateau. Over time, the district has witnessed significant infrastructure development to support both intra-city movement and regional connectivity; growing population and expanding city limits have added new demands on Pune’s roads and public transport. Suburban trains, a developing metro, PMPML buses, auto-rickshaws, private vehicles, and an airport now serve the district, but traffic congestion, uneven planning, and changing commuter needs also continue to shape daily life. Together, these factors offer a view of Pune’s evolving transport landscape and the challenges that come with it.

History

Ancient Trade Routes & Centers

Pune district’s location has long placed it at the crossroads of important inland and coastal trade routes in western India. Situated between the Konkan coast and the Deccan plateau, the region formed a natural corridor for the movement of goods, people, and ideas from the ports of Sopara, Thane, and Kalyan inland to centres such as Nashik, and Paithan.

One of the most significant ancient routes was the Naneghat Pass, located in the Junnar region of the Western Ghats. This mountain pass connected the port cities on the Arabian Sea with the Satavahana capital at Paithan in the Deccan interior. The name Naneghat, meaning ‘coin pass’ is said to refer to its function as a toll point; near the pass, a large 2,000-year-old stone urn is believed to have been used to collect tolls from traders. Brahmi inscriptions found at Naneghat record donations from rulers of the Andhra-Satavahana dynasty, including King Vedisiri, who is credited with improving the pass to facilitate trade.

The town of Junnar where Naneghat lies itself has been an important trading and administrative centre for over two thousand years. Its strategic position on this trade corridor allowed goods such as spices, oil, raw sugar, and salt to move between the coast and the Deccan hinterland. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a 1st-century CE Greek text, notes that Roman ships anchored at ports like Kalyan and Sopara, bringing goods that were then transported inland through Junnar and the Naneghat Pass to reach Paithan.

Many scholars hold that trade routes across the Deccan region (where Pune lies) supported the growth of Buddhism. Many Buddhist cave sites near Junnar, Karla, and Bevda were established along these routes and likely served as resting places for travelling monks and merchants. During the rule of the Western Kshatrapas, it is said that several of these cave complexes were expanded or newly carved, suggesting that local trade continued to flourish during this period.

Aside from these major local centres, Pune is also believed to appear in early international records. Interestingly, it is noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1885)that some British-era scholars believed “Poona” (as Pune was then known) might correspond to Pumiata, a city named by the geographer Ptolemy around 150 CE. Although this connection remains uncertain, it points to Pune’s position and significance within ancient trade networks known to early geographers.

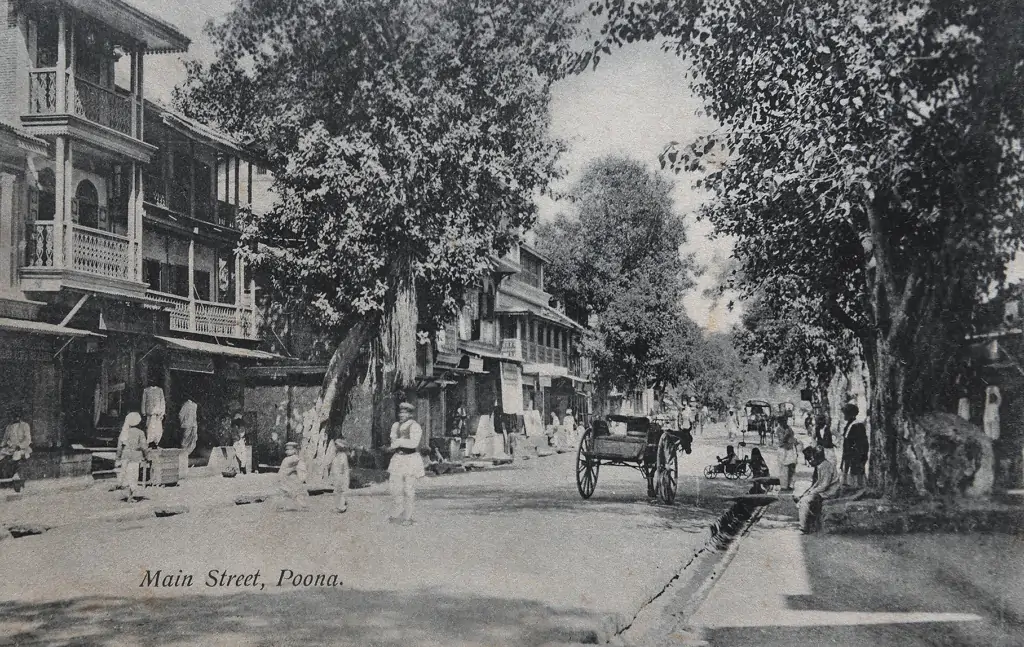

TraditionalMeans of Conveyance

Alongside the long-distance trade routes that shaped the region’s early growth, everyday travel within Pune historically relied on simpler means of conveyance. Before independence, it is said that tongas (horse-drawn vehicles) and bicycles were widely used within Pune’s Peth areas, serving as common modes of local transport for residents and traders alike. For longer journeys beyond the city, bullock carts remained the primary option, carrying passengers and goods between Pune and surrounding villages and markets.

In the years since, tongas and bullock carts have gradually declined with the advent of concrete roads and motor vehicles.

Modes of Transportation in the District

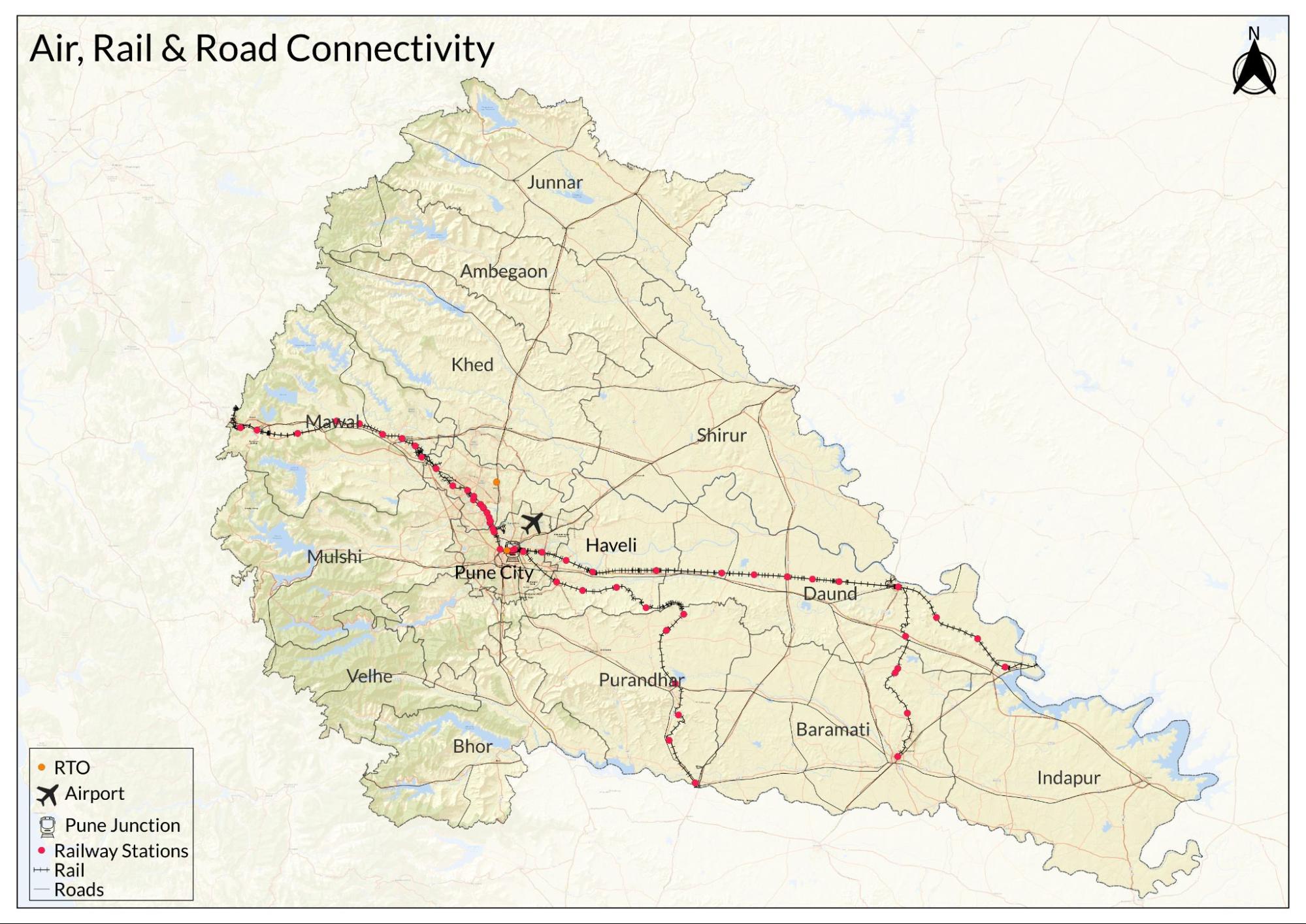

Train and Rail Systems

Pune district falls under the Central Railway Zone and is part of the Pune Railway Division, which manages suburban and long-distance services in the region. The city’s suburban rail network, known as the Pune Suburban Railway (PSR), plays an important role in daily commuting for residents travelling to and from surrounding areas. The PSR operates a line connecting Pune Junction to Lonavala, with local trains stopping at stations such as Akurdi and Shivaji Nagar, providing access to the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC) area. An additional line extends from Pune Station to Daund, serving commuters in the eastern parts of the district.

Pune Junction is the district’s main railway station and handles long-distance services linking the city with other districts and states. Many people commute daily between Pune and nearby districts using inter-district trains and passes such as the MST Dabba, which help facilitate regular travel for work and study.

The development of Pune’s rail system began in 1858 with the first train service between Khandala and Pune. Interestingly, at that time, there was no direct rail connection to Mumbai; trains from Mumbai terminated at Khopoli, and passengers completed the remaining stretch to Khandala by a palanquin! Over time, the network expanded to reach Solapur and Miraj by 1886. The present Pune railway station building was opened on 27 July 1925 and is recognised as a national heritage structure.

Improvements in rail services gradually reduced travel times. Journeys between Mumbai and Pune, once requiring a full day, now typically take two and a half to three hours. The Deccan Queen, introduced as the first superfast train on this route, remarkably, played a notable role in shortening journey times and strengthening the link between the two cities. Over time, more routes and trains have become part of this network, supporting the district’s continued growth and daily movement of people and goods.

Cycling Infrastructure

Cycling has long formed part of Pune’s urban transport system, especially during the late 20th century when it became closely linked with the city’s growth as an educational centre. In the 1990s, bicycles were among the most affordable means of daily travel for students and workers, earning Pune the colloquial title of the “city of cycles.” As bus services expanded and public transport became more accessible, however, the use of bicycles for regular commuting gradually declined.

In recent years, there have been numerous efforts to revive the city’s glory days of cycling but they have been met with failure due to its obsolete nature. One such attempt was PEDL, a public bicycle-sharing scheme launched in 2017. The system used bright green bicycles fitted with QR codes for easy rental and return. Piloted in neighbourhoods such as Aundh, Baner, and Balewadi, the scheme ran for three months but faced challenges. Many residents pointed out that the problem was never a shortage of bicycles but the lack of safe, usable roads for cyclists.

Perhaps to address this, after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) introduced painted cyclist lanes on some main roads. However, these lanes were marked without physical barriers or proper planning, often narrowing roads further and worsening traffic congestion. With no clear separation from cars, the painted lanes have become convenient spots for illegal parking and encroachment, making them unreliable and sometimes unsafe for cyclists to use at all.

Illegal parking and obstructions in these designated lanes have become common, and poor enforcement have left these lanes largely ineffective. Today, bicycles are rarely seen on city roads outside of early morning hours, when they are mostly used by fitness riders rather than daily commuters; and it appears that cycling has lost the place it once held and bicycles have largely disappeared from Pune’s daily conveyance network.

Overview of Bus Networks

Buses remain one of the main modes of daily conveyance for residents in Pune district. The city’s bus services are jointly managed by two municipal corporations: the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) and the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC). Before 2007, these areas operated separate systems—Pune Municipal Transport (PMT) for PMC and Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Transport (PCMT) for PCMC. In 2007, both services were merged under the Pune Mahanagar Parivahan Mahamandal Ltd (PMPML) to streamline operations and improve access across the urban region.

PMPML now operates a mixed fleet of CNG and electric buses, running daily from 5:30 am until midnight, including weekends and holidays. With over 2,000 buses on the road each day, the network covers a wide range of routes that connect neighbourhoods within the city as well as some surrounding villages and taluka headquarters. The fleet includes various types of buses, each marked by a distinctive colour or purpose.

Blue Buses are older CNG models used mainly for shorter routes, with fares capped at ₹40. Green Buses are newer CNG vehicles that operate over longer distances.

The Punyadasham Buses, locally called ‘Dai Mai Bus’, are red buses with a maximum fare of ₹10 and are available at major hubs such as Pune Station, Mahatma Gandhi Bus Stand, Deccan, Swargate, and Shivajinagar. Ladies Special Buses operate during peak hours, reserved for women passengers. A night service known as Ratrani covers a small number of late-night routes, estimated by residents to include four to five main lines.

State Transport buses, often referred to locally as “Yeshti” or “Eshti,” continue to run beyond PMPML’s city limits, serving state highway stops and longer inter-district routes.

PMPML’s fare system includes various passes aimed at affordability where a daily pass costs for about ₹40, a monthly pass for ₹900, a student monthly pass for ₹750 (with proof of enrolment), and a student yearly pass for ₹5,000.

When it comes to the daily experiences of locals and commuters, many say that overcrowding remains one of the main challenges when using the bus network. Although buses have designated seats for women and people with disabilities, these are often occupied by other passengers when services are full. Boarding and exiting can be difficult during peak hours, despite conductors enforcing a rule that requires passengers to board at the rear door and exit at the front to maintain flow inside the bus. Many commuters also point out that ticket payments still rely entirely on cash, even though digital payment is now widespread elsewhere.

Passengers also frequently highlight the condition of bus stops as another concern. Many stops lack clear name signs, shelters, or seating. This becomes particularly uncomfortable during the monsoon, when travellers have no protection from rain while waiting.

In addition to these everyday issues, many residents feel that routes have not kept pace with the city’s growing population. Suburban areas such as Baner, Aundh, Pashan, and more remain poorly connected despite increasing demand. Commuters also note the absence of a live tracking system, which means they rely on static timetables and personal estimates, often made unreliable by delays from traffic, construction, and ongoing metro works. Together, these factors continue to affect the reliability and comfort of Pune’s bus services for daily users.

Metro Services

Pune is among the few cities in Maharashtra and India with operational metro services. The Pune Metro currently runs the Purple Line, which connects PCMC (Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Corporation) to Ruby Hall Clinic, and the Aqua Line, linking Vanaz to Ramwadi, with an interchange at Civil Court (Shivajinagar) station. The section between Chinchwad and Ruby Hall Clinic, passing through Civil Court, was inaugurated in August 2023.

Additional metro lines are under construction, with extensions planned to reach areas such as Baner, Aundh, and other growing neighbourhoods. These sections are expected to open for service within the next two years.

Since its launch, the metro has gradually seen an increase in daily ridership, with peak crowds usually observed in the mornings around 8 am and in the evenings between 6:30 and 7 pm. Compared to city buses, the metro runs more frequently, with trains arriving every 15 minutes and providing air-conditioned coaches.

Metro stations feature digital ticketing through mobile phones, electronic scanning, and security checks similar to those found at airports. Passengers access the platforms by stairs or elevators. Stations include clocks, route maps, clear lighting, and benches for waiting passengers. Inside the trains, there are benches, overhead handrails, and LED screens that display upcoming stops, with announcements made in Marathi, Hindi, and English.

Autos & Shared Vehicles

Auto rickshaws, three-wheeled vehicles, remain one of the most widely used means of local transport in Pune. However, they are often noted for inconsistent service, with drivers sometimes refusing short trips or waiting for more profitable fares. In nearby areas such as Lonavala, meters are commonly ignored and app-based bookings through services like Ola are restricted. Locals attribute this to the area’s dependence on tourism, with many drivers relying on weekend and peak-season earnings.

Still, where certain bus routes lack coverage, rickshaws often become the only practical option for short-distance travel. Affordability remains a concern for daily users. Following nationwide fare revisions in 2021, the minimum fare for rickshaws in Pune was set at ₹25—higher than the recommended ₹21—due to demands from auto unions citing fluctuating CNG prices, which power many vehicles.

Interestingly, despite the reputation for higher costs that autos now have, in the early 21st century they were seen as a more affordable option. Rather than carrying just one passenger, many autos operated as shared vehicles. However, rising operational costs and increasing fuel prices have led to a decline in their use. As one autowallah noted, these growing expenses and financial pressures have significantly reduced the availability of shared autos in the city’s transport network.

Other than this, six-seater rickshaws, known locally as “tum tums,” were once a familiar sight in Pune. These vehicles often carried more than six passengers despite the name, but concerns about their high emissions led authorities to ban them from city limits in 2002. Remnants of this mode of transport can still be found along Satara Road, Viman Nagar, and near the Swargate Bus Depot.

Another informal mode of local travel is the privately operated Omni or Suzuki van, which resembles a small grey school van and can carry around 8 to 10 passengers. These vans function like flexible carpools, offering cheaper fares than standard rickshaws. They do not follow fixed schedules but are frequently seen in residential areas and can be flagged down when needed.

App-based ride services such as Uber, Ola, and Rapido are increasingly popular alternatives to conventional autos. Many commuters prefer these services because they can be booked directly to the doorstep, fares are agreed in advance, and air-conditioned cabs are especially preferred during the hot summer months.

A newer entrant, InDrive, has also begun operating in Pune, offering both cab and rickshaw services. Unlike standard ride-hailing platforms, InDrive allows passengers and drivers to negotiate fares before confirming a booking. Travellers propose a price based on distance; drivers can accept, reject, or counter with their own fare, allowing both parties to agree on a mutually acceptable cost.

Cars & Two-Wheelers

Two-wheelers and cars remain the most widely used personal modes of transport in Pune. The steady rise in the number of private vehicles, however, in many ways, has contributed to traffic congestion and raised concerns about air pollution within the city.

Among two-wheelers, the Honda Activa is the most commonly seen scooter on city roads, valued for its reliability and moderate price. In recent years, electric scooters such as the Ather have begun to appear more frequently, especially among college students who benefit from state subsidies for electric vehicle purchases. Many see this shift as one way to address the environmental impact caused by petrol-based vehicles.

For cars, locals say that models like the Maruti Suzuki Swift and Honda City are commonly owned across the district. Both Maruti Suzuki and Honda remain trusted brands for middle-income households, known for offering budget-friendly models suited to city driving. More recently, newer brands such as Kia and Morris Garages (MG) have gained popularity and are now a familiar sight on Pune’s streets.

The move toward electric vehicles is slowly increasing. In addition to electric scooters, cars such as the Tata Nexon EV have started appearing more often despite having entered the market only a few years ago.

Air Travel

Pune district is served by the Pune International Airport, which handles both domestic and limited international air traffic for the city and surrounding areas.

The airport’s origins date back to the 1930s, when it was established as a military airfield. First known as RAF Poona, it was formally established in 1939 to provide air security for Bombay (now Mumbai) and hosted World War II squadrons equipped with de Havilland Mosquito, Vickers Wellington bombers, and Supermarine Spitfire fighters. In May 1947, control of the airfield passed to the Royal Indian Air Force. Over the decades, the airport gradually expanded its facilities and operations. In 2005, it was granted international status, enabling direct international flights and improved passenger services.

However, for many residents, the airport has also become a point of frustration due to frequent overcrowding and congestion. Nitin Gadkari (2024), the current Minister for Road Transport & Highways, remarked that Pune Airport resembles a “Swargate bus stand,” a comparison that reflects the experience of many travellers who face long queues and limited space.

The existing terminal often struggles to handle the rising passenger volume, prompting calls for urgent upgrades and expansion. An ongoing dispute between the Air Force and the Airports Authority of India (AAI) over operational control and available land has further complicated plans for improvement. Proposals to create additional terminal space within the restricted area have encountered operational and regulatory challenges. Many Pune residents continue to push for better airport infrastructure to ease congestion and keep pace with the city’s growth as a regional hub.

Ferries & Water Transport

Before modern roads and bridges became common, ferries were an important part of Maharashtra’s transport system, connecting villages and towns across rivers and enabling regional and inter-district travel. It is recorded in the colonial district Gazetteer (1885) thirteen public ferries in operation at the time, divided into four categories based on how frequently they ran. Routes included locations such as Khed, Bhima, Pimpri Khurud, and Sangrun in Haveli Taluka, among others.

These services were typically operated by Koli boatmen, who managed the crossings and maintained the boats. Interestingly, it is noted that many ferries used flying bridges to help move people, carts, and goods across river stretches.

Traffic Map & Congestion

Traffic congestion has become one of the most pressing challenges faced by residents in Pune today. According to the 2023 TomTom report, Pune ranks as the 7th most congested city in the world, a situation that shapes daily life for countless commuters. While the district’s transport network has expanded over time, rapid growth and uneven planning have created persistent difficulties alongside improved access.

Historically, locals say travel in Pune was mostly contained within the Mula–Mutha river boundary. Over the last six decades, the city’s expansion—driven in part by the rise of the IT sector—has created new residential and commercial clusters beyond this core. Neighbourhoods such as Baner, Aundh, and Hinjewadi, once on the city’s edge, are now heavily populated. Many residents note that this growth happened without consistent planning, resulting in roads that are often narrow and unable to handle today’s traffic volumes.

Frequent changes in local administration and shifting project priorities have further affected road conditions. Long-term residents recall stalled flyover projects and roads repeatedly dug up for new works. For example, the University flyover, built just over a decade ago, was demolished in 2020 to make way for a planned two-level replacement. Ongoing metro construction in areas like Baner and Aundh has added to daily congestion, with constantly shifting routes and narrowed lanes.

Seasonal monsoons bring potholes, waterlogging, and damage that require repeated repairs, further testing commuters’ patience.

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)System

To address growing traffic congestion, the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) launched the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system in 2008, making Pune the second city in India, after Ahmedabad, to adopt this approach. The plan aimed to encourage more people to use public transport by introducing dedicated bus lanes on existing roads and intended to make bus services faster, more reliable, and more affordable.

However, in practice, the system has faced significant challenges. One key issue, as many residents point out, is the limited number of buses, which has often led to overcrowding and long waits.

Another problem that locals pointed out Although the BRT included modern bus stops with shelters, seating, and automatic doors, many of these facilities have not been properly maintained. During the monsoon, water frequently collects at stops, and broken automatic doors have allowed rainwater to accumulate inside. Concerns about safety, especially for women, have also been raised due to poor lighting and the often isolated locations of some stops.

Enforcement of BRT lane rules has also proved difficult. While cars, scooters, and bikes are technically banned from the BRT corridors, many drivers use them to bypass traffic without facing penalties, largely due to limited traffic police presence. This misuse has reduced the system’s effectiveness and speed. Over time, many BRT corridors have stopped operating as intended, adding to congestion on nearby routes instead of easing it.

Residents have also noted a lack of clear channels to raise complaints or report problems specifically related to the BRT. Although PMPML manages regular bus services and helplines for issues like late buses, it does not directly handle BRT feedback, as the system was funded through national schemes like the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) and the Sustainable Urban Transport Project (SUTP). As of May 2024, there remains no dedicated point of contact for BRT-related issues.

In conversations, many local commuters describe the BRT as an example of an idea that fell short in practice, adding to infrastructure problems rather than solving them.

AttitudeTraffic Rules & Regulations

Pune’s traffic challenges are compounded by a widespread disregard for traffic rules among many daily commuters. Signal violations, riding without helmets, neglecting seatbelts, illegal U-turns, and driving on footpaths are common occurrences across the city. Residents often point out that heavy traffic itself pushes people to break rules, creating what some describe as a “herd mentality” where such behaviour becomes routine.

Speed limits are widely treated as general suggestions rather than strict limits. Traffic police, who are mostly stationed at major intersections, often struggle to manage the high volume of vehicles, especially during peak hours, and frequently work with limited facilities and difficult conditions. Many locals note that this mix of public impatience, limited enforcement, and gaps in traffic management continues to make road safety a persistent concern.

Communication Networks

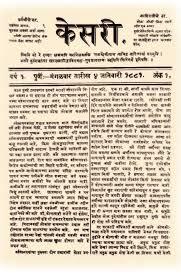

Newspapers & Magazines

Pune’s local publications have long played a central role in daily life. Many well-known Marathi papers were started or grew here, including Sakaal, Lokmat, Loksatta, Punya Nagari, Pudhari, and Maharashtra Times (‘Ma Ta’). These titles still reach homes, corner stalls, and reading rooms across the city and district every morning.

Some of India’s earliest and boldest publications also came from Pune. In 1881, Kesari was founded by Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar to speak directly to Marathi readers under colonial rule. Editorials such as ‘Sarkarcha Doka Thikanavar aahe ka?’ (Is the government’s brain even working?) and ‘Deshache Durdaiv’ (The misfortune of the country) challenged British authority and stirred public debate. Despite repeated attempts by the British to silence Tilak through charges of treason, the paper survived — and Tilak’s grandson, Jaywant Tilak, later expanded it with daily issues and a Sunday supplement that continues to this day.

Equally important to Pune’s print history is the Chitrashala Press, founded in 1878 in Sadashiv Peth by Vasudeo Bapuji Kanitkar and Vishnu Krishna Chiplunkar. Long before modern printing presses, Chitrashala produced Marathi books, magazines, and striking colour lithographs of Devis and Devtas, Maratha leaders, and freedom fighters. During the Swadeshi Movement, these prints—signed ‘Chitrashala Press, Poona’—brought nationalist ideas into homes and marketplaces, reaching towns and rural areas alike. Though the original wada was demolished after 1991, Chitrashala Chowk still marks the site. Some of these prints remain preserved in private collections and local museums.

Today, Pune’s reading culture remains diverse. Hindi readers turn to papers like Nava Bharat, while English titles such as The Times of India and The Indian Express remain part of daily routines in schools, offices, and homes. Journalism courses in local colleges keep this long tradition alive, with new writers and editors adding to the city’s long record of print and public debate.

What’s on the Billboards? A Look at Pune’s Hoardings

What appears on a city’s billboards often says a great deal about its economy, its aspirations, and how it grows. In Pune, this is clear from the rows of advertisements that line busy streets and intersections. Areas such as Laxmi Road, FC Road, Deccan, and Kasba Peth are filled with hoardings for jewellery and clothing shops, especially during festivals like Akshaya Tritiya, Ganesh Chaturthi, Gudi Padwa, and Diwali. These ads, notably, focus on seasonal sales and auspicious days to buy gold and are centered around local customs and beliefs.

Smaller advertisements are also common, appearing on poles, buses, and in newspapers. Many promote coaching centers for class 10th and 12th exams and competitive entrance tests like JEE and NEET, often showcasing successful students to attract new enrollments during critical exam cycles.

Smaller ads are also common—on poles, in buses, and across local newspapers. Many promote coaching centres for students appearing for Class 10th and 12th board exams or competitive tests like JEE and NEET. It is common to see billboards showing photos of ‘toppers’ to attract new enrolments during exam cycles.

Advertisements also appear on PMPML buses, which earn revenue not only through ticket sales but also through these large exterior ads. Buses—especially the Green and Blue lines—often carry promotions for coaching classes, local exhibitions, masalas, pickles, and similar everyday products.

Real estate ads are especially visible. Billboards along the Mumbai–Bangalore highway and other major routes promote new housing projects and rental schemes, pointing to the city’s steady expansion and the value placed on property investment.

Yet this growth has also brought pushback from locals concerned about its impact on the city’s look and environment. Many people point out that the endless cycle of construction is tied to the relentless stream of ads encouraging real estate sales. Many concerned residents lament that this often comes at the cost of green spaces and trees.

Festival grounds and pandals have not been spared either. Corporate advertisements now cover stages and processions during Ganesh Chaturthi and other events. Many residents feel this flood of ads has changed how the city looks—and, for some, even weakens the meaning and community spirit behind these celebrations. This tension between commerce and culture remains part of the larger story of a city trying to balance rapid change with what people want to preserve.

Graphs

Road Safety and Violations

Transport Infrastructure

Bus Transport

Communication and Media

Sources

Airport Authority of India. 2018.Executive Summary: New Integrated Terminal Building, Reconstruction and Expansion at the Pune Civil Enclave (Pune Airport).Pune: Airport Authority of India.https://mpcb.ecmpcb.in/notices/pdf/Executive…

Ashish Kuvelkar. Making Bombay-Poona a Reality: Trains Across Maharashtra’s Bhor Ghat. Google Arts & Culture.https://artsandculture.google.com/story/maki…

Atikh Rashid. 2023. Hidden Stories: How a Pune-based lithograph press founded in 1878 became a flagbearer of Indian nationalism. The Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pun…

Dheeraj Bengrut. 2021. Experts to Preserve and Maintain Heritage Pune Railway Station Building. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Dheeraj Bengrut. 2022.Nation turns 75: From tongas to buses to metros, Pune’s public transport finally comes of age. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

ET Online. 2024. Commuters in Pune Spend Over 5 Days in Traffic On Average: TomTom Report. Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/in…

Gazetteer Department. 1885 (reprinted 1992). Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency:Poona District, Volume XVIII, Part II. Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

PMB Desk. 2024. New Pune Airport Terminal Faces Backlash Over Operational Shortcomings. Pune Mirror.https://punemirror.com/pune/others/new-pune-…

Pune Municipal Corporation. 2017.Comprehensive Bicycle Plan for Pune.Resolution Number 693, dated 14 December 2017. Pune: Pune Municipal Corporation.https://punecycleplan.wordpress.com/wp-conte…

TNN. 2022. Auto Fare Rs 25 for First 1.5km in Pune from September 1. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Yogesh Sangle. 2024. Pune Airport is Looking Like Swargate Bus Stand: Gadkari. Pune Mirror.https://punemirror.com/pune/politics/pune-ai…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.