Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Types of Farming

- Betelnut Farming

- Fish Breeding

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Use of Technology

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMC

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Impact of Changing Climate Conditions

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

RAIGAD

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

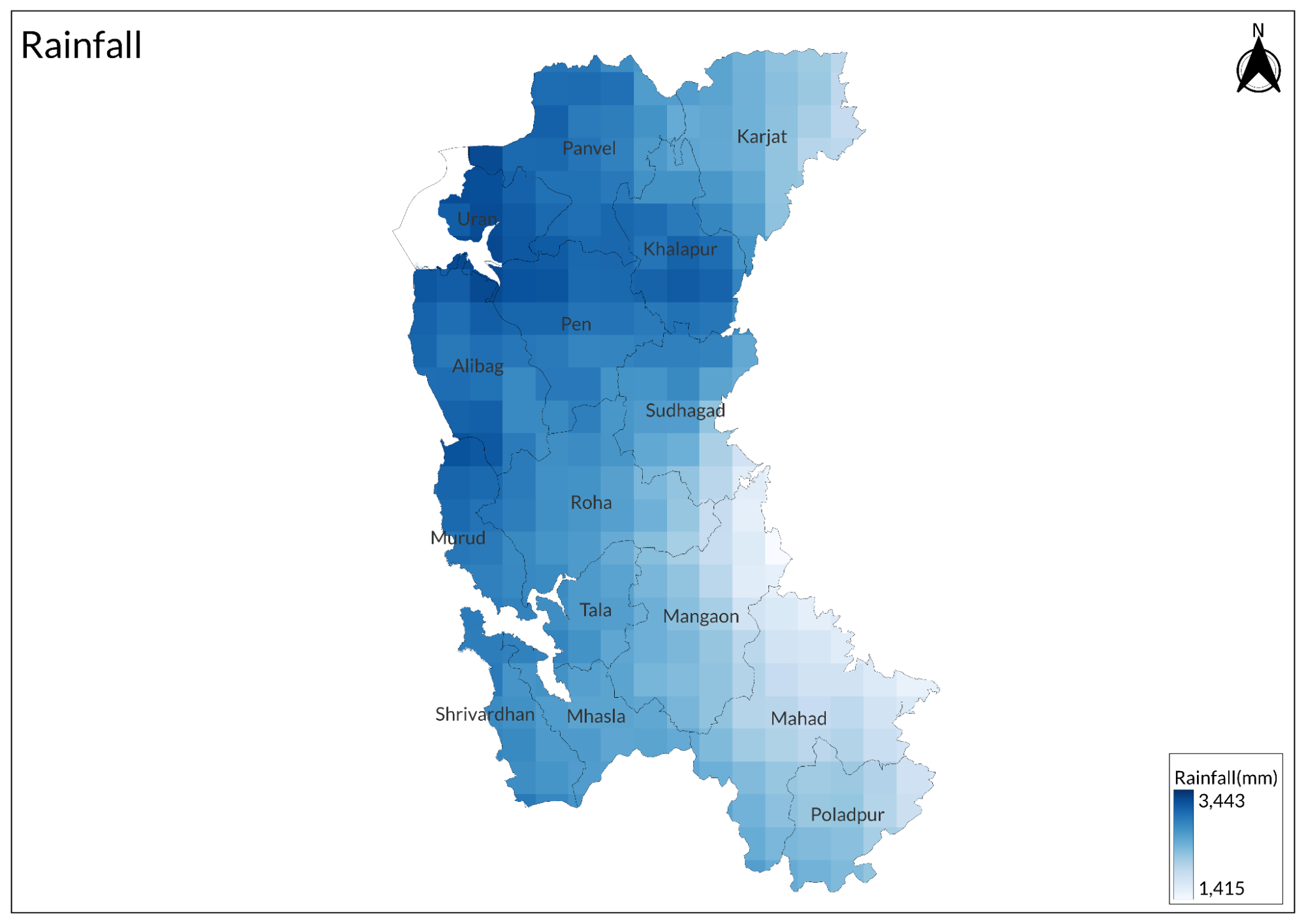

Raigad district serves as a crucial agricultural center in Maharashtra, known for its diverse crop production and rich farming traditions. The region heavily depends on the monsoon season for the rainfall essential to sustain crop growth, with paddy as the foundation of its agricultural economy.

Crop Cultivation

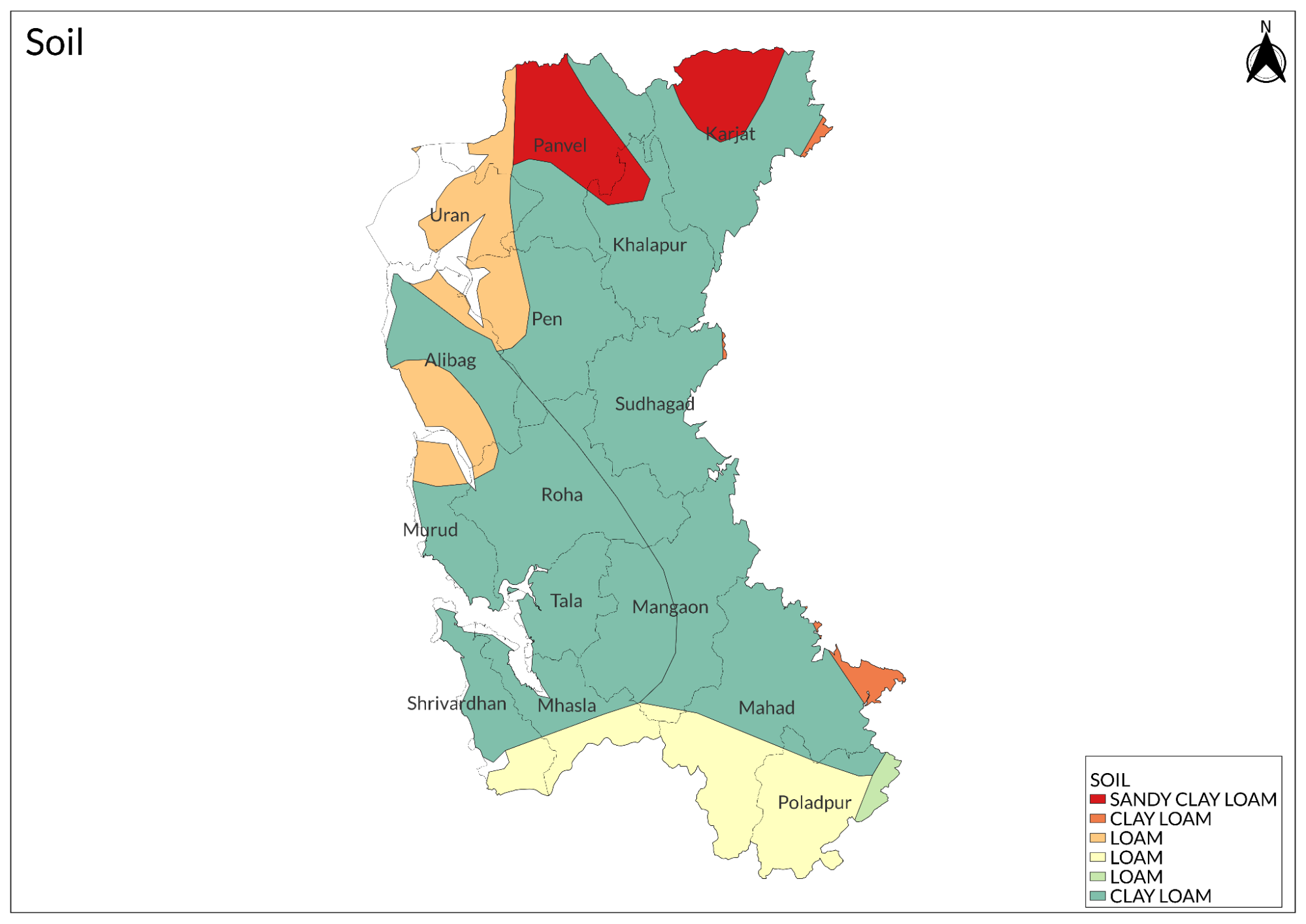

Raigad district has a diverse agricultural landscape, with rice as the primary crop cultivated throughout the year. Other significant crops include ragi (nachni), barnyard millet (vari), yellow peas (val), toor, sesame (teel), and a variety of fruits such as mangoes, cashews, and coconuts.

The district boasts two primary types of agricultural land: fertile areas near the mountains and flatlands, as well as salt-affected regions known locally as kharpattichi jamin. Among the common rice varieties cultivated are Jaya, Suvam, and the historically significant Karjat Kolam. Another notable variety is Tychun, which features short grains; villagers often humorously refer to shorter individuals as ‘Tychun’ after this rice.

During the Kharif season, major crops include paddy and Nagali, along with fruits such as mangoes and cashews. Additionally, the district is home to betelnut plantations, which are also a significant agricultural product.

Agricultural Communities

Farmers and their families in the region work tirelessly year-round to secure their livelihoods. To supplement their income, they cultivate vegetables, pulses, and other crops alongside their main harvest. In some areas, fish breeding (shettali) is also practiced.

Commonly grown vegetables include cucumbers, tomatoes, chilies, padwal, ladyfinger, sweet potatoes, and leafy greens like math and palak. Farming families typically keep a portion of these vegetables for their consumption, selling the surplus in nearby markets. They prepare for the market day by gathering and bundling the vegetables into toplis (round baskets) the night before. Rising early around 3 am, they arrive at the wholesale market by 4 am to sell their produce.

In these remote regions, community collaboration remains strong. Villagers come together to help one another with various farming activities, from sowing seeds to harvesting crops and preparing them for market. The boundaries of farmlands (shetache bandh) must be established each year, and outlets for excess water need to be created. Women often assist each other in these tasks, taking turns to support different families in what is known locally as ‘parka’ or ‘handa.’ A commonly used phrase illustrates this practice: "Patlanchya shetat 2 parka jhalya," which means that the group has assisted in Patil's farm activities twice.

However, labor shortages are becoming a pressing issue. Many young people are migrating to Mumbai for jobs, leaving fewer hands available for farming tasks. In the betel nut plantations, this shortage has forced farmers to send their betel nuts to Alibaug for deshelling. An old wholesaler warns that, due to both natural and man-made challenges, betel nut production may cease entirely in the coming years.

Family farms are essential to middle-aged and older farmers in the district, who remain committed to cultivation despite numerous challenges. In contrast, younger generations are increasingly drawn to opportunities in Mumbai and Pune for education and jobs, aiming for a higher standard of living with less physical labor. A cause of concern for the older generation. Still, many young people hold full-time jobs while also engaging in farming or aquaculture as a side hustle. Some, especially students with agricultural backgrounds, are experimenting with innovative crops and plantations like drumsticks, dragon fruit, strawberries, mangoes, and papaya.

Types of Farming

Raigad is known for its varied farming practices that reflect the region's agricultural diversity. Key types of farming include paddy cultivation, betelnut plantations, and fish breeding. Each method has its unique techniques and challenges, shaped by local conditions and traditions.

Betelnut Farming

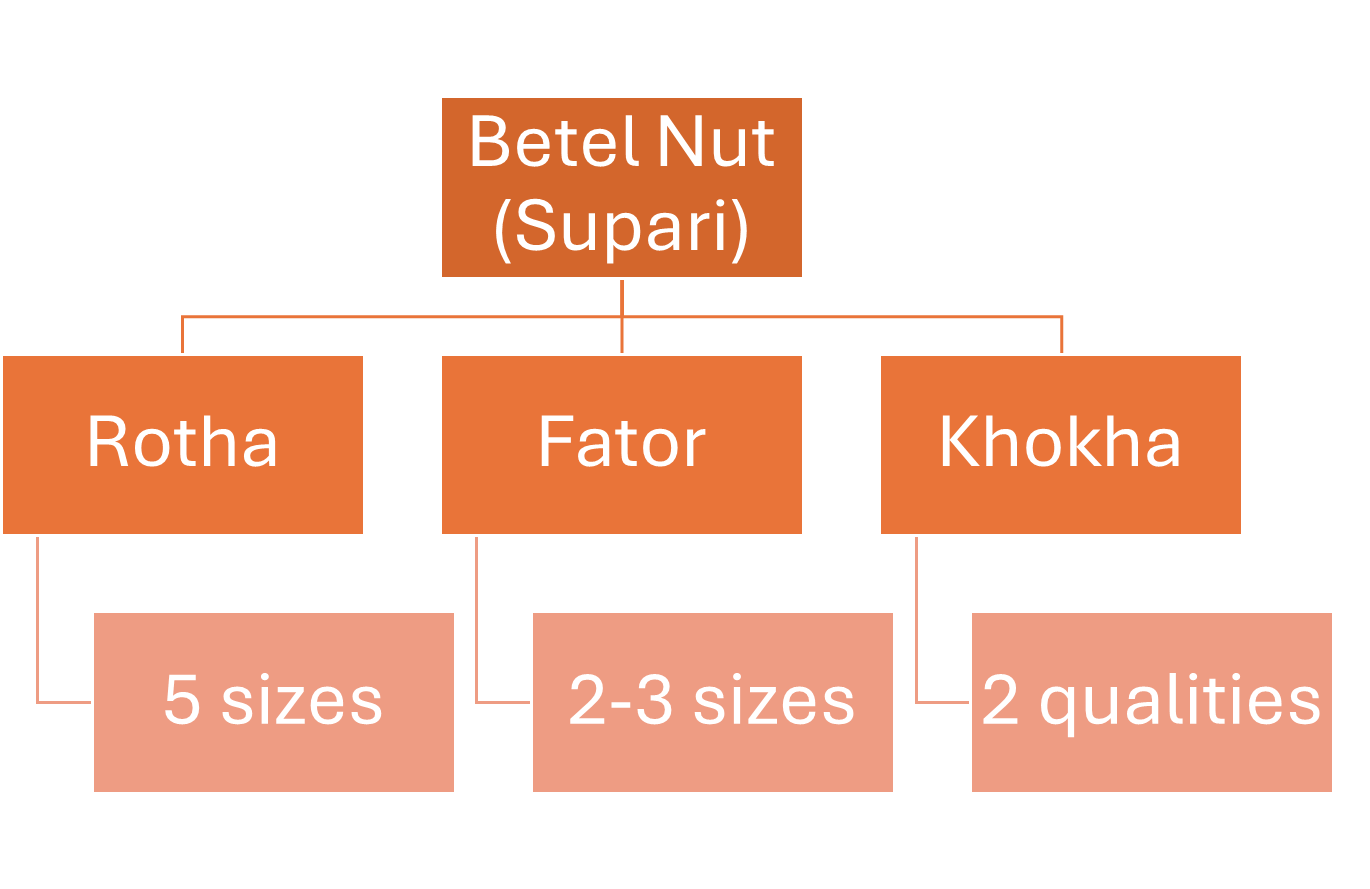

Betel nut cultivation is a significant agricultural activity in Raigad, with plantations in the district dating back around 150 years. The renowned 'Rotha' variety from Shrivardhan taluka is famous worldwide and is exported globally. After establishing a betel nut plantation, it takes approximately five years for the trees to start bearing fruit. Farmers replant one-year-old saplings in holes dug two feet deep in the plantation area. The fruits typically begin to grow around October and are ready for harvest by January or February. When the betel nuts turn orange or red, they are harvested either by climbing the trees or using a knife-like tool attached to a long stick.

The harvested nuts undergo a process called Pastalne, where the skin is peeled to facilitate drying. Once dried, they are deshelled in a process known as Nisne, after which they are ready for use. Betel nut (supari) serves as a cash crop for many farmers. Before 2020, Shrivardhan produced around 4 to 5 lakh kilos of supari. However, production dropped to about 1 to 1.5 lakh kilos post-2021 due to the Nisarg cyclone, which severely affected local plantations. The region boasts about nine varieties of supari.

Being a coastal region, farmers in Raigad face numerous challenges each year. Floods, landslides, untimely rains, and cyclones frequently devastate their crops, leaving them empty-handed and disheartened. Local farmers state that the recent Nisarg cyclone in 2020 significantly damaged betel nut plantations in Shrivardhan Taluka, leading to a notable decline in overall production.

In many remote villages, such as Maleghar Bedi and Mantri Bedi, families face ongoing challenges with limited access to drinking water. To tackle this issue, farmers have devised a system of satha vihiri or satha taki (tanks) that are placed beneath the outlet pipes on their roofs to collect and store rainwater. These tanks are designed to block sunlight, which helps prevent insect breeding and keeps the water clean and safe for consumption. Ironically, despite being a coastal region, many farmers still lack access to drinking water. Furthermore, the absence of proper roads forces villagers to navigate knee-deep, waterlogged soil (chikhal) during emergencies, complicating their daily lives and making access to essential services even more challenging.

Fish Breeding

Fish breeding is a traditional practice in the district, particularly in farm lakes (Shettali), and is especially common in the kharpatti (saltwater lands). Some popular fish varieties include Fantoosh, Chimnya, Kolambi, Jitada, Shivda, Katla, Rui, Khaul, Boit, Chimbori, Mrigal, Gavtya, Saipres, M M Tilapiya, Calcutta Katla, Goa Pomfret, Gavti Pomfret, and Bodhi. Like vegetables, these fish are sold in local markets and consumed regularly.

Recently, due to labor shortages and rising wages, many farmers are turning to fish breeding or aquaculture. They dig lakes on their farmlands to cultivate these fish. Typically, two or three different-sized pits are created to facilitate the transfer of fish as they grow, ensuring that larger fish don’t prey on smaller ones. Once the lakes are filled with water, baby fish (1-2 inches long) are introduced, often purchased from Chennai or Calcutta.

Around the end of July, these small fish are placed in a smaller lake. Farmers provide about 20 kilograms of feed daily, made from leftover rai and groundnut plants (known as penda in Marathi). This dried hay is soaked overnight and formed into balls, which are then fed to the fish. It takes about 4-5 months for the fish to reach maturity. By November, they typically weigh between 1 to 1.5 kilograms each and are ready for sale or consumption. On Sundays, when many locals prefer non-vegetarian meals, farmers can earn around 8,000 to 9,000 rupees, with earnings ranging from 3,000 to 7,000 rupees on other days.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Raigad is a region steeped in age-old agricultural practices that have been passed down through generations. These time-honored techniques reflect a deep connection to the land and a profound understanding of the local environment. Among these practices, paddy cultivation holds a prominent place, reflecting the time-honored wisdom that guides farmers in nurturing this vital crop.

The journey of paddy cultivation begins with churning the soil and dividing the land into squares of 10x10 or 10x15 feet, where seeds are planted. Once these seeds grow, the baby shoots are taken out and are sorted as single twigs. An important step while sorting the shoots is removing the unnecessary twigs. This activity is called ‘Bendni’.

After the soil is plowed, these single twigs are planted in neat rows. As the crop develops, fertilizers are applied to nourish the plants and protect them from insects and rodents. In earlier times, when cooking was done over wood fires, ash accumulated, which was collected along with dry and wet household waste in a pit near the farmer’s home. This organic matter would decompose over time, creating a natural fertilizer. Today, farmers often use readily available fertilizers such as Sufala, Ujwala, Urea, and Goli khat, communicated in specific quantities like 18 by 18 or 16 by 16. Additionally, natural waste from earthworms and droppings from hens, sheep, and goats are also utilized.

Around the festival of Ganeshotsava, rice grains begin to form, a stage locals refer to as ‘Garbhdharana,' the formation of a baby in the womb. The stage when the rice grains begin to form is referred to as ‘bhat tatoris lagla’ in the local language. At this point, the grains are still soft and not fully developed. If a grain is picked and pressed, a milky white substance oozes out.

By Diwali, the grains harden, signaling that harvest time is near. The cutting process, called ‘Kapni,’ then begins. The harvested crops are bundled into small bunches and stacked in an aesthetically pleasing manner, creating rows of rice known as ‘Urvi’ (singular: Urva).

Once all the crops are harvested, the land is leveled, and pits are dug. Farmers strike the rice corn against the sides of these pits to collect the grains in a process known as ‘Malni.’ Finally, women and men gather the grains in a pan called ‘sup’ and shake it high into the air. This helps separate lightweight debris, leaving only fully formed rice grains, a process referred to as ‘Harapna.’

This entire process demands significant physical energy, fitness, and patience. If the harvest goes well, farmers state that they can earn around 10,000 to 12,000 rupees per acre of rice produced. Beyond their daytime work in the fields, farmers and their families engage in various tasks at home. For example, ‘Sandhali’ ropes are crafted from hay, typically by those in their 40s and 50s.

In Karjat, a unique custom of letting the Kathkaris cultivate a certain area of land free of rent is practiced. The upland seedbed, like a rice seedbed, is thatched with branches, burnt, and manured with ashes. When the rains have begun, the bed is ploughed and the grain sown. Like rice, the nachni or vari is not left to ripen where it grows but is planted in another piece of upland, mal varkas, which by plowing or hoeing has been made ready to receive it. Both grains ripen in October, when, as the straw is useless, the heads are plucked and the stems left standing. The heads are taken to the threshing floor, and the grain is beaten out with sticks. As they are used only in the form of a meal, nachni and vari do not require the careful cleaning that rice does.

Use of Technology

Over the past decade, the introduction of various technological interventions has started to reshape the agricultural landscape of Raigad, driving improvements in productivity, sustainability, and farmers' income. One of the primary ways in which technology is transforming agriculture in Raigad is through mechanization. Traditionally, farming in the region was heavily reliant on manual labor, with farmers using bullock-drawn plows and manual tools for most operations, from tilling and planting to harvesting. However, with increasing labor costs and a shrinking labor force, mechanization has become an essential strategy for improving farming efficiency.

Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) in Raigad have played a pivotal role in promoting mechanization by offering training, machinery access, and expert guidance. They have actively encouraged farmers to integrate modern tools into their farming practices to improve productivity.

One example of a successful technological intervention is Shri Ganesh Mhaskar, a rice farmer from Roha. Facing issues such as labor shortages and increasing wages, Shri Mhaskar approached KVK for assistance in 2010, as reported on their website. Previously, he relied on family labor and hired help, using traditional farming implements. His annual income from rice cultivation was about Rs. 1 lakh. After consulting with KVK, he adopted mechanized solutions, starting with a power tiller for puddling his rice fields.

The power tiller not only reduced the cost of puddling by 50% but also saved significant time. Motivated by this success, Shri Mhaskar purchased his power tiller and began offering custom hiring services to other local farmers. This new income stream added Rs. 50,000 to his annual earnings.

In addition to the power tiller, KVK introduced the vertical conveyor reaper for harvesting. After successful on-farm trials, Shri Mhaskar incorporated this technology into his operations. The reaper reduced harvesting costs by 70% compared to traditional manual methods and saved valuable time, allowing him to focus on other farming tasks. The combination of mechanized puddling and harvesting not only improved his farm's efficiency but also boosted his overall income by an additional Rs. 50,000 annually.

Through these technological interventions, Shri Mhaskar's experience highlights how mechanization here is being used to increase operational efficiency, reduce labor costs, and enhance farm profitability.

Institutional Infrastructure

Agriculture and infrastructure development are closely linked, with changes in one often influencing the other. Typically, when one grows, the other tends to shrink, a pattern observed across many regions. These dynamics are especially evident in rapidly urbanizing regions, where agricultural land is frequently converted to accommodate new infrastructure projects.

Raigad district, like many such regions, has experienced notable land use changes in recent years. Urbanization, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development have significantly altered the landscape. A study (2024) on Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection in the Kal River Basin of Raigad, using remote sensing data, offers valuable insights into how infrastructure development is increasingly influencing agriculture in this area specifically.

The study indicates that the built-up area in the Kal River Basin has expanded by 0.31%, from 7.78 km² in 2017 to 9.22 km² in 2021, highlighting the rapid urbanization taking place. As urban areas expand, agricultural land is often converted into housing or industrial zones, thereby reducing the space available for farming. Furthermore, infrastructure developments such as road construction and industrial zones can fragment agricultural land, making it less accessible and disrupting traditional farming practices. Additionally, land cover changes near water bodies, such as rivers, may have broader implications for water resource management, which is critical for sustaining both agricultural and urban growth in the region.

Market Structure: APMC

Raigad district is home to several Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) that play a crucial role in the organized trading of agricultural produce. These APMCs, along with their sub-markets, serve as important hubs for transactions between farmers, third-party buyers, and the government.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1 |

Karjat |

1955 |

Prakash Nanu Farat |

49 |

|

2 |

Panvel |

1957 |

Narayan Gomaji Gharat |

1 |

|

3 |

Roha |

1962 |

Ganpat Kisan Mhatre |

1 |

|

4 |

Pen |

1957 |

Jayprabha Prafull Mhatre |

NA |

|

5 |

Khalapur |

1963 |

NA |

16 |

|

6 |

Mahad |

1962 |

Sridhar Bhaskar Sakpal |

NA |

|

7 |

Mangaon |

1964 |

Ram Pandarang More |

2 |

|

8 |

Murud |

1963 |

Santosh Joma Kambali |

NA |

|

9 |

Alibaug |

1963 |

Kamlakr Govind Sakhale |

NA |

Raigad's APMCs handle a diverse range of agricultural commodities. Key items traded in these markets include bulrush millet, unhusked paddy, rice (paddy-husk), other cereals like wheat and sorghum (jawar), as well as other pulses such as ragi (nachni).

Despite the presence of APMCs across the district, many farmers and middlemen still prefer to sell their produce in local sabzi mandis (vegetable markets), bypassing the formal APMC system. This highlights the continued reliance on informal markets, even with the availability of structured trade platforms.

Farmers Issues

In recent years, the government has introduced several concession policies to support agriculture, offering subsidies on essential inputs like pesticides, fertilizers, pumps, cutters, and equipment, as well as for aquaculture. There are also subsidies available for building wells and farm lakes. Furthermore, it has been reported that some farmers in the region are eligible for income support of ₹12,000—₹6,000 from the state government and ₹6,000 from the central government.

While these schemes are publicly available online, with a fully digitized application process designed to ensure that the benefits reach the right recipients, many farmers are still unaware of the assistance they can access. This gap in awareness points to a critical need for more effective outreach and education within the farming community, ensuring that the benefits of these government programs reach those who need them most.

Impact of Changing Climate Conditions

Raigad, located in the coastal Konkan region of Maharashtra, is a key agricultural district, especially known for its rice cultivation. However, like many other agricultural regions worldwide, Raigad is increasingly experiencing the adverse effects of climate change. As global temperatures rise and rainfall patterns become more erratic, the agricultural landscape in Raigad is changing.

Recent studies on climate change projections for Maharashtra have highlighted significant shifts in temperature and rainfall patterns by 2050. In Raigad, the projected temperature change ranges between −1°C and +2.7°C, while the percentage change in rainfall varies from 3.0% to 11.7%. These projections suggest that the region will experience relatively moderate to higher increases in rainfall, combined with a slight increase in temperature.

Rice, a staple food crop in Raigad, is particularly sensitive to changes in temperature and precipitation. Based on the climate projections for the district, the rice production in Raigad is expected to increase by 0.46% to 30% by 2050. This rise in production can be attributed to higher rainfall compensating for any negative effects of temperature increases. In essence, the combination of moderate temperature changes and increased rainfall appears to create a favorable environment for rice cultivation.

Interestingly, the Kolhapur district, with similar climatic trends, has also shown that a slight dip in temperature combined with a rise in rainfall can lead to significantly improved rice yields. This observation offers hope that even in the face of global warming, there is a potential for some regions to adapt and thrive with the right balance of climatic changes.

One of the most critical findings from the study is the importance of rainfall in maintaining rice yields. In Raigad, where rainfall is projected to increase moderately, this change is seen as beneficial for rice production. Increased precipitation helps mitigate the negative effects of temperature increases, which can often stress crops like rice, leading to reduced yields. Therefore, in Raigad, the forecasted moderate to higher rainfall could help sustain or even increase rice yields, as long as the temperature increase remains within manageable limits.

While higher rainfall can have a positive effect, temperature changes are still concerning. Even a slight increase in temperature (projected at 1.5°C to 2°C by 2050) can affect crop growth stages, such as flowering and grain filling in rice. High temperatures, especially during critical stages of growth, can cause heat stress, leading to reduced yields and lower grain quality. Additionally, the combination of climate change and undeterred human activities on the environment could pose challenges.

According to a 2023 Deccan Herald article, experts and long-time residents have emphasized several key concerns, particularly the growing vulnerability of hillsides, soil instability, and the increased risk of landslides. As climate change usually leads to more extreme weather events, including heavy rainfall in shorter periods, the region is seeing an increase in soil saturation. When soil becomes overly saturated with rainwater, it loses its ability to support the weight of rocks and soil on the slopes, making the area more prone to landslides. In Raigad, agricultural areas, especially terraced fields on hilly slopes, are increasingly at risk. Landslides have already become a significant issue in several talukas across the district, underscoring the need for greater attention to these risks.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Gopal Krishna, Mahfooz Alam, Rabi N. Sahoo, and Chandrashekhar Biradar. 2021. Impact of Climate Change on Crop Production and Its Consequences on Human Health.Recent Technologies for Disaster Management and Risk Reduction: Sustainable Community Resilience & Responses, Earth and Environmental Sciences Library, Springer.https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/97…

Kumari, Neelam, Ayare, B. L., Bhange, H. N., Ingle, P. M., & Kasture, M. C. 2024. Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection Using Remote Sensing in the Kal River Basin, Raigad District, Maharashtra, India. Vol. 14, no. 10.International Journal of Environment and Climate Change.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384…

Kvkraigad.orghttp://www.kvkraigad.org/uncategorized/mecha…

Msamb. Comhttps://www.msamb.com/ApmcDetail/Profile

NABARD. 2022-23. Potential Linked Credit Plan: Raigad. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/te…

PTI. 2023. Down a slippery slope: Climate change, landslide and heavy rain push Raigad villagers to edge of despair. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com/india/maharasht…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.