Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Birds

- Forest Reserves

- Karnala Bird Sanctuary

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Illegal Mining and Deforestation

- Coastal Erosion

- Industrial Pollution

- Waste Management

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Mangrove Conservation

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- H. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- C. Wildlife Projects (Area and Expenses)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Matheran: Asia’s Only Automobile-Free Hill Station

- Sources

RAIGAD

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Raigad district, situated along the Konkan coast of Maharashtra, is a sanctuary for a wide variety of flora and fauna, enriched by its tropical forests, mangroves, and lush green spaces. This district hosts wildlife, including leopards, deer, wild boars, and numerous bird species such as kingfishers and herons, especially in the vicinity of mangrove habitats. However, with the passage of time, the district has been facing environmental issues like coastal erosion, industrial pollution, among others.

Physical Features

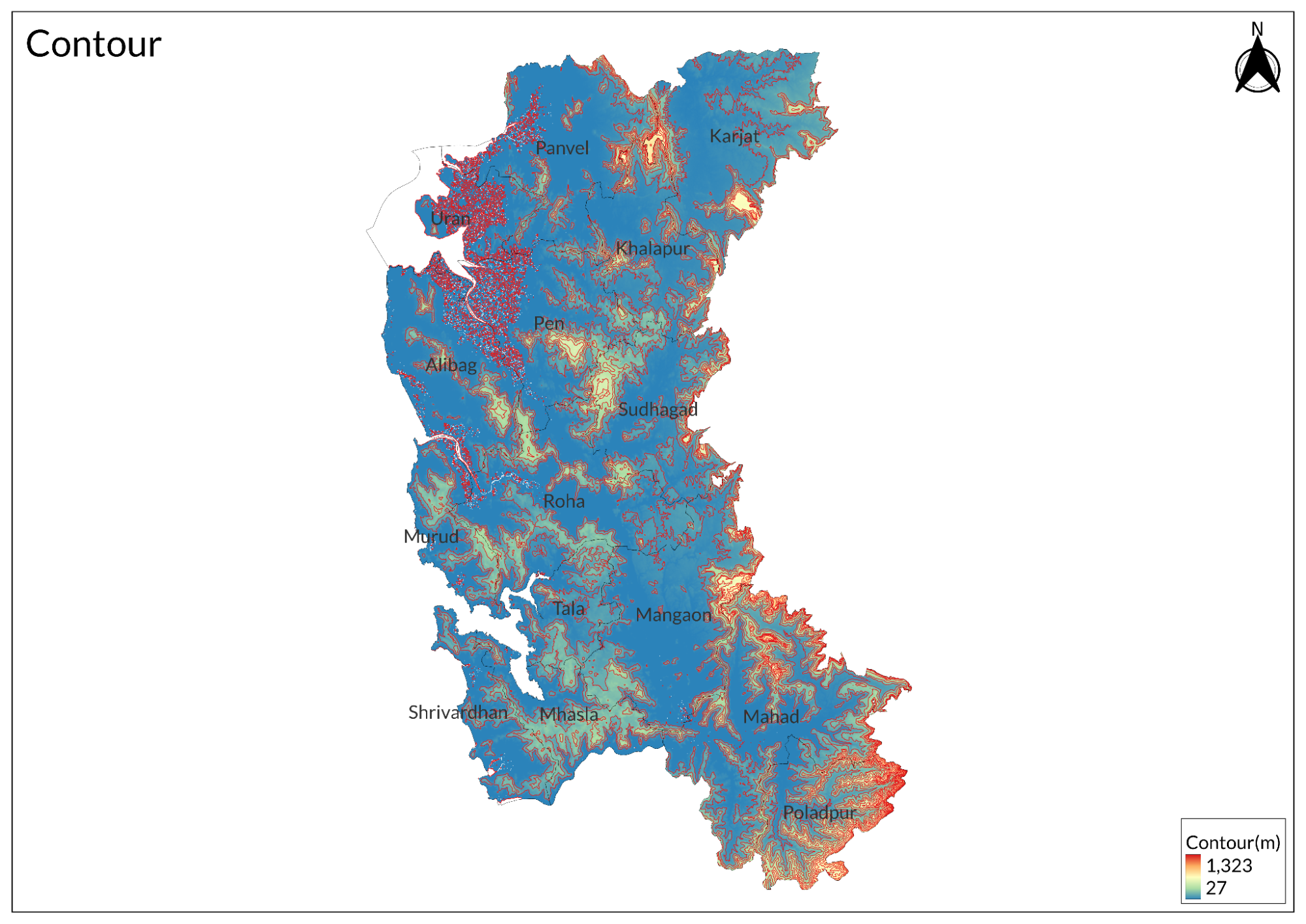

Raigad district stretches along Maharashtra's western coast, encompassing three distinct physiographic zones. The eastern boundary is formed by the Sahyadri ranges (Western Ghats) with elevations ranging from 600-800 meters, featuring the historic Raigad Fort at 820 meters. The ranges are characterized by flat-topped plateaus locally known as "sada," steep escarpments, and deep valleys. Notable peaks include Mahuli, while the Matheran plateau stands as a prominent geographical feature. The central region consists of undulating terrain between the mountains and sea, marked by multiple river valleys with elevations between 100-300 meters and alluvial plains along watercourses.

The western portion features a 122-kilometer coastline along the Arabian Sea, distinguished by numerous creeks, bays, and estuaries. Major creek systems include Dharamtar, Mandad, and Kundalika, which penetrate deep inland. The coast alternates between rocky headlands, sandy beaches, and mudflats, creating diverse coastal ecosystems. Natural harbors at Rewas, Dighi, and Mandwa punctuate the coastline. The district's drainage pattern varies from dendritic in the Ghats to parallel near the coast, with several hot springs and cave formations enriching its geographical diversity. This varied topography creates distinct microclimates that support diverse ecosystems while influencing settlement patterns and development across the region.

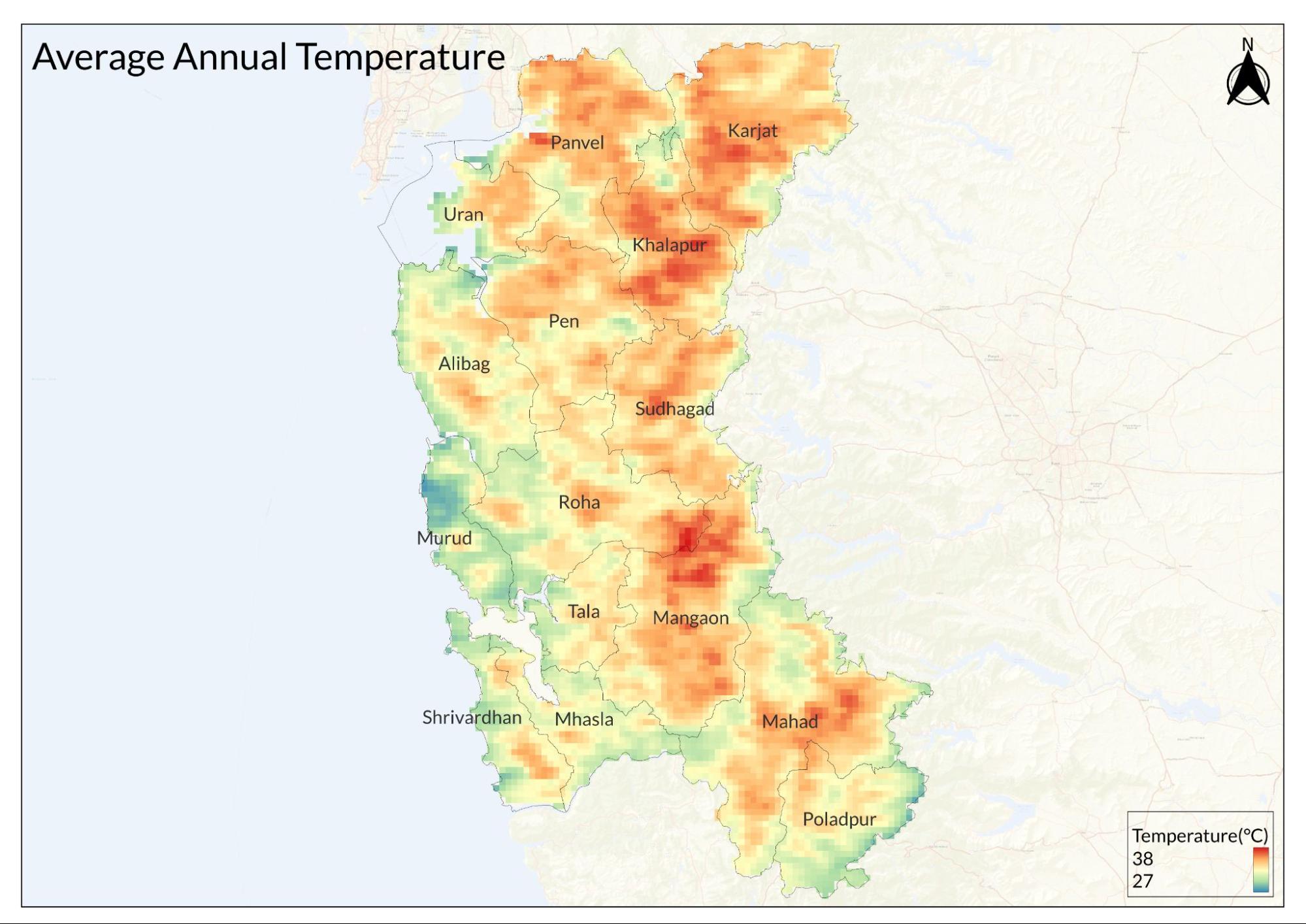

Climate

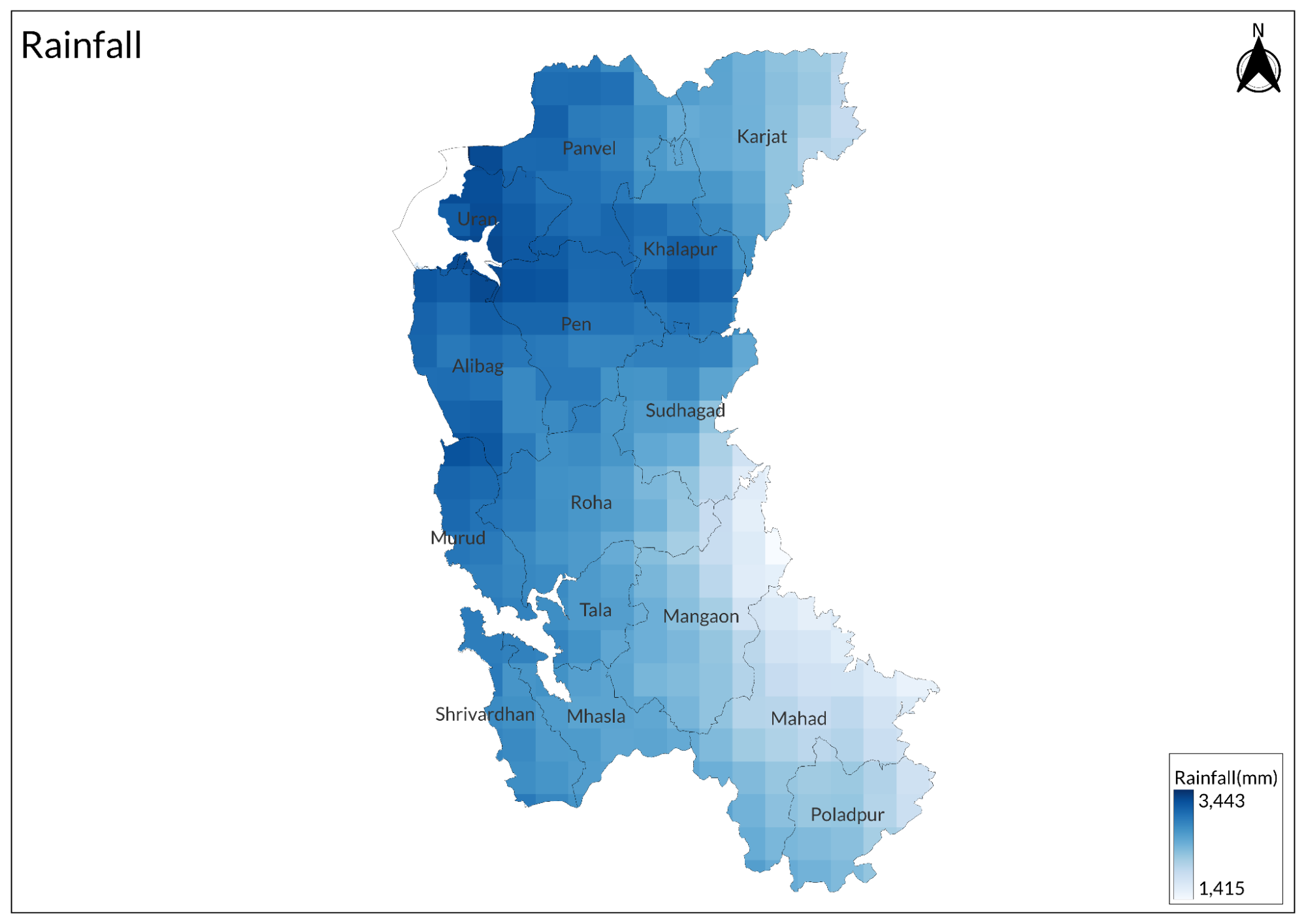

Raigad's climate is shaped by three dominant features: its coastal location, the Western Ghats, and the monsoon system. Temperatures range from a comfortable 16°C in winter to a hot 38°C in summer, with April being the hottest month (highs 38°C, lows 24°C) and January the coldest (highs 31°C, lows 16°C). The Arabian Sea moderates coastal temperatures, creating milder conditions along the shore compared to inland areas near the Sahyadri ranges.

The monsoon defines the district's rainfall pattern, with peak precipitation in July-August. July sees 97% probability of daily rain, averaging 0.79 inches (20.1mm), accompanied by peak humidity of 90%. Wind speeds reach their maximum in July (17.0 mph) and minimum in April (9.0 mph). The climate shows clear seasonal progression: hot dry summer (March-June), monsoon (June-October), humid post-monsoon (October-November), and mild winter (December-March). Notably, coastal areas receive less rainfall than the Sahyadri regions, while enjoying moderate sea breezes year-round.

Daylight varies from 13.3 hours in June to 11.0 hours in December. Cloud cover is heaviest during monsoons, with July having only 19% clear skies, while January enjoys the clearest conditions. This diverse climate pattern, along with the district's varied topography, creates distinct microclimates that influence local agriculture and living conditions across different regions of Raigad.

Geology

The geological foundation of the Raigad district is characterized by extensive basaltic lava flows, known as the Deccan Traps, dating from the Upper Cretaceous to Lower Eocene age. These formations emerged from long, narrow fissures in the Earth's crust, spreading horizontally in sheet formations. The lava flows exhibit remarkable thickness, reaching 762 meters around the Matheran plateau and 865 meters near Raigad fort. Individual flows vary in thickness, ranging from a few meters to over 25 meters. The basalt in the district manifests in two primary forms: aphinitic basalt, which is hard and compact, and vesicular amygdaloidal basalt, containing silicate minerals.

The district's geological structure is further enriched by numerous intrusive features, particularly in its northern regions, where multiple dykes are present. A notable geological formation includes a ring dyke at Mahad, adding to the complex geological landscape. The plateau tops in both the middle and coastal tracts showcase significant laterite and bauxite deposits, particularly in regions like Roha, Murud, Shriwardhan, Pen, and Matheran. These laterite formations vary in thickness from a few meters to 24 meters, contributing to the region's mineral wealth and influencing its topographical characteristics.

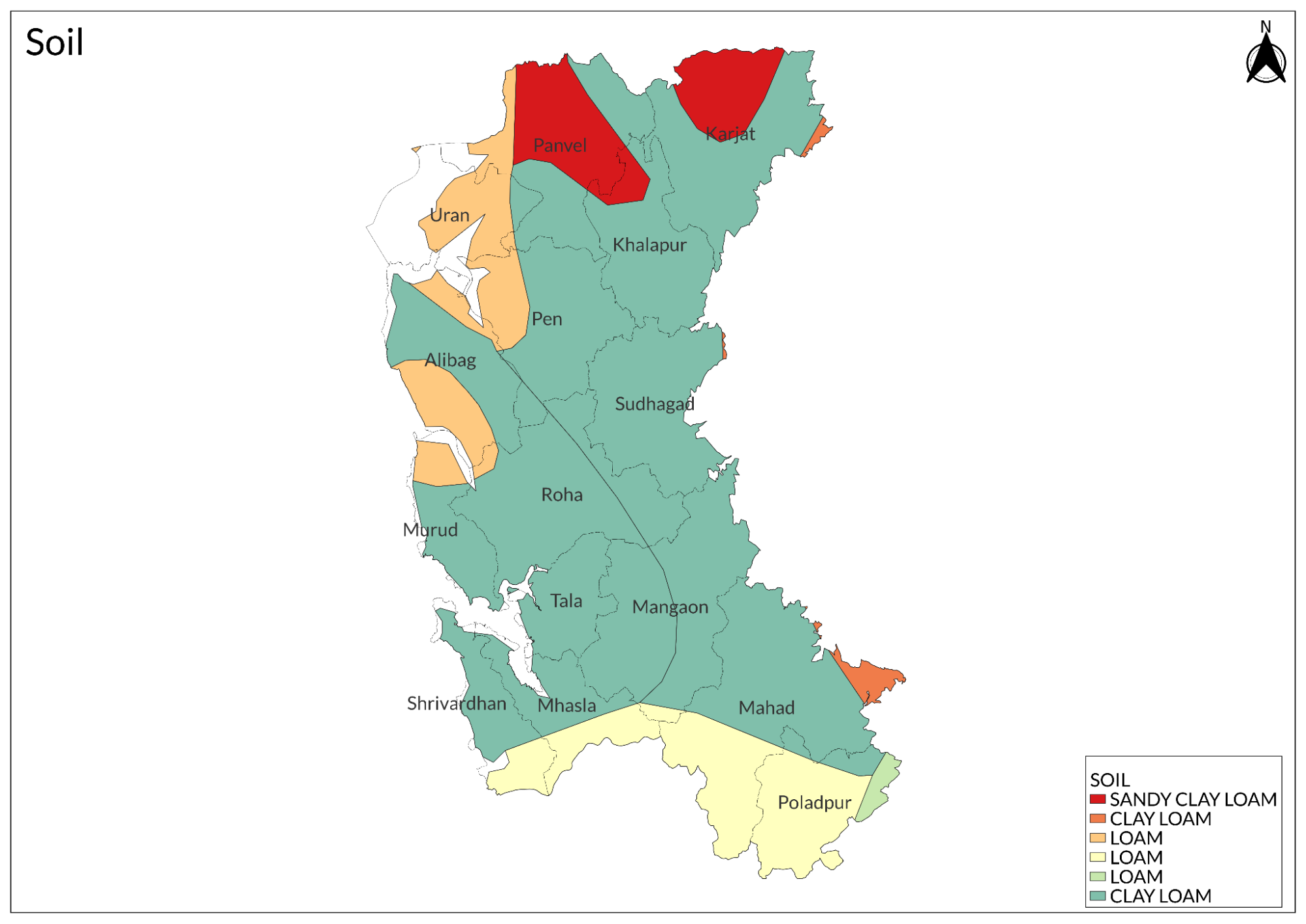

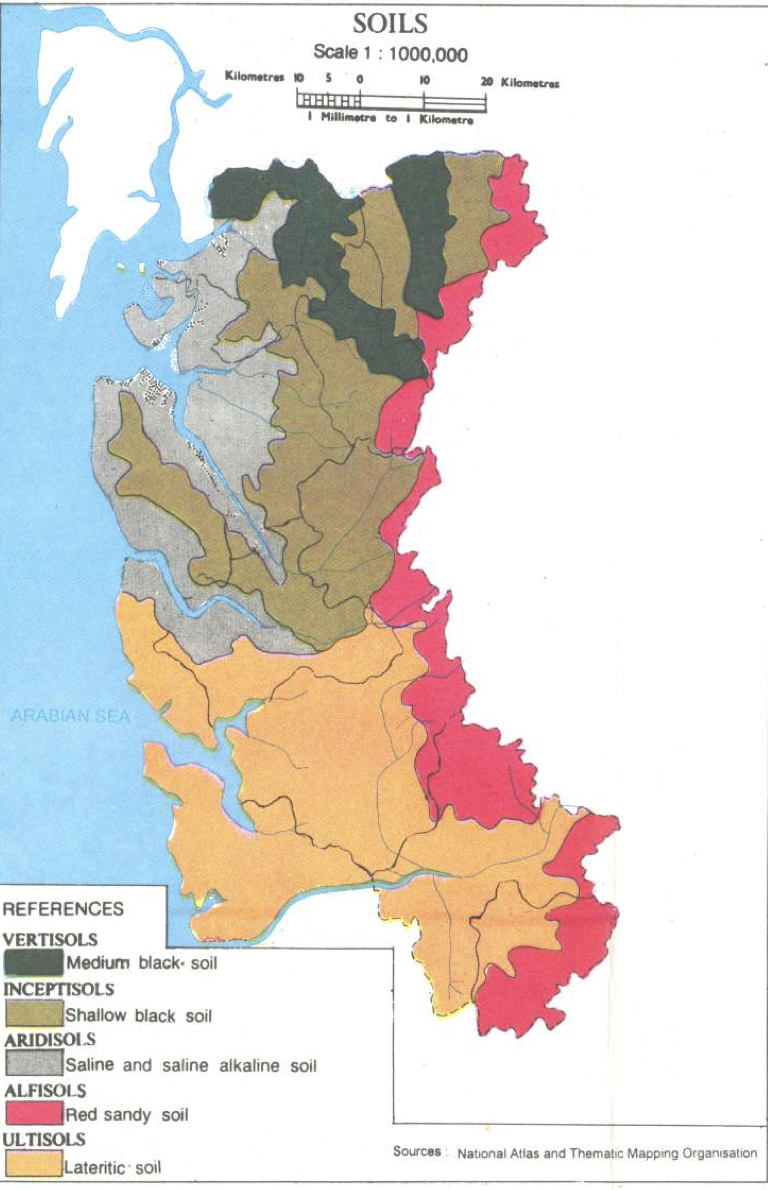

Soil

Coastal areas like Alibag, Murud, Mhasla, and Shriwardhan feature distinctive coastal alluvium containing sand, shale, and calcareous material. This soil type supports coastal vegetation, particularly coconut plantations. The marine influence creates unique conditions for specialized agricultural practices. The highland regions exhibit lateritic soils, notably in Shriwardhan, Murud, Mhasla, and Pen. These areas are marked by reddish, porous soil formations. Notable variations include yellowish-brown bauxitic soils in Shriwardhan and specific alluvial deposits in the Kalundri river basin near Panvel. These soil patterns determine local cultivation choices and agricultural productivity.

Minerals

The mineral resources in Raigad, while not extensive, play a significant role in local construction and industrial activities. The district's geological formation, dominated by Deccan Trap basalt, provides various building materials, while its coastal and riverine geography ensures a steady supply of sand for construction purposes.

Rivers

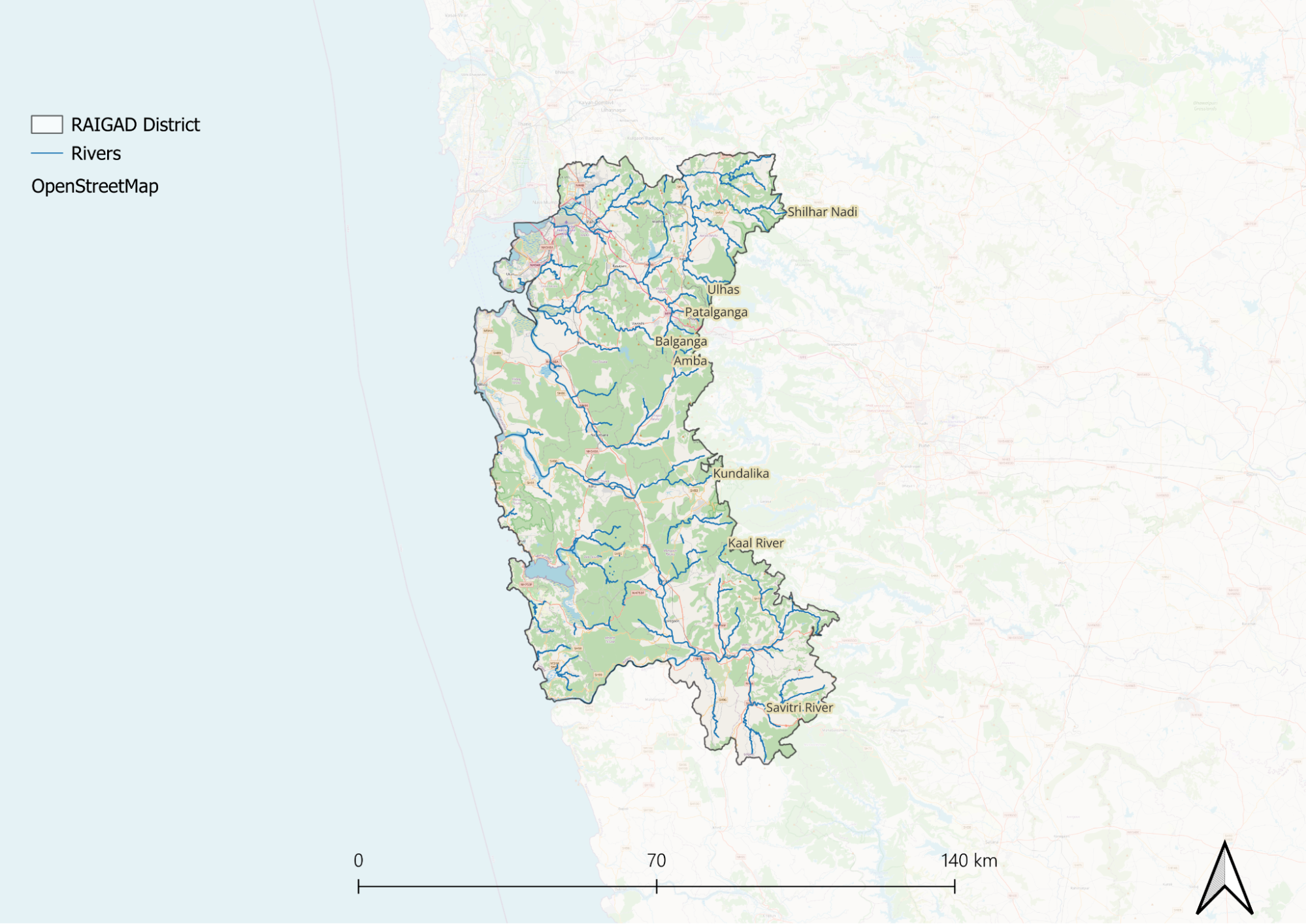

Raigad's river system is organized into three distinct geographical regions, each with its own network of waterways. The northern region is drained by four major rivers: the Ulhas, Patalganga, Amba, and Panvel Creek. These rivers form significant watersheds and are crucial for the region's agriculture and water supply. They originate in the Sahyadri ranges and flow westward, creating fertile valleys and supporting numerous settlements along their banks.

The central region of the district is primarily drained by the Kundalika and Mandad rivers. These waterways have carved deep valleys through the landscape and are characterized by their westward flow pattern. Along their course, they create rich alluvial deposits that support intensive agriculture. The river valleys also facilitate transportation routes and have historically influenced settlement patterns in the central district.

The southern portion of Raigad is dominated by the Savitri River and its tributaries. This river system creates an extensive network of waterways that shape the southern landscape. A distinctive feature of Raigad's river system is that all rivers flow westward, originating in the Sahyadris and emptying into the Arabian Sea. This creates a series of estuaries and creeks along the 160 km coastline, forming natural harbors and supporting diverse coastal ecosystems.

Botany

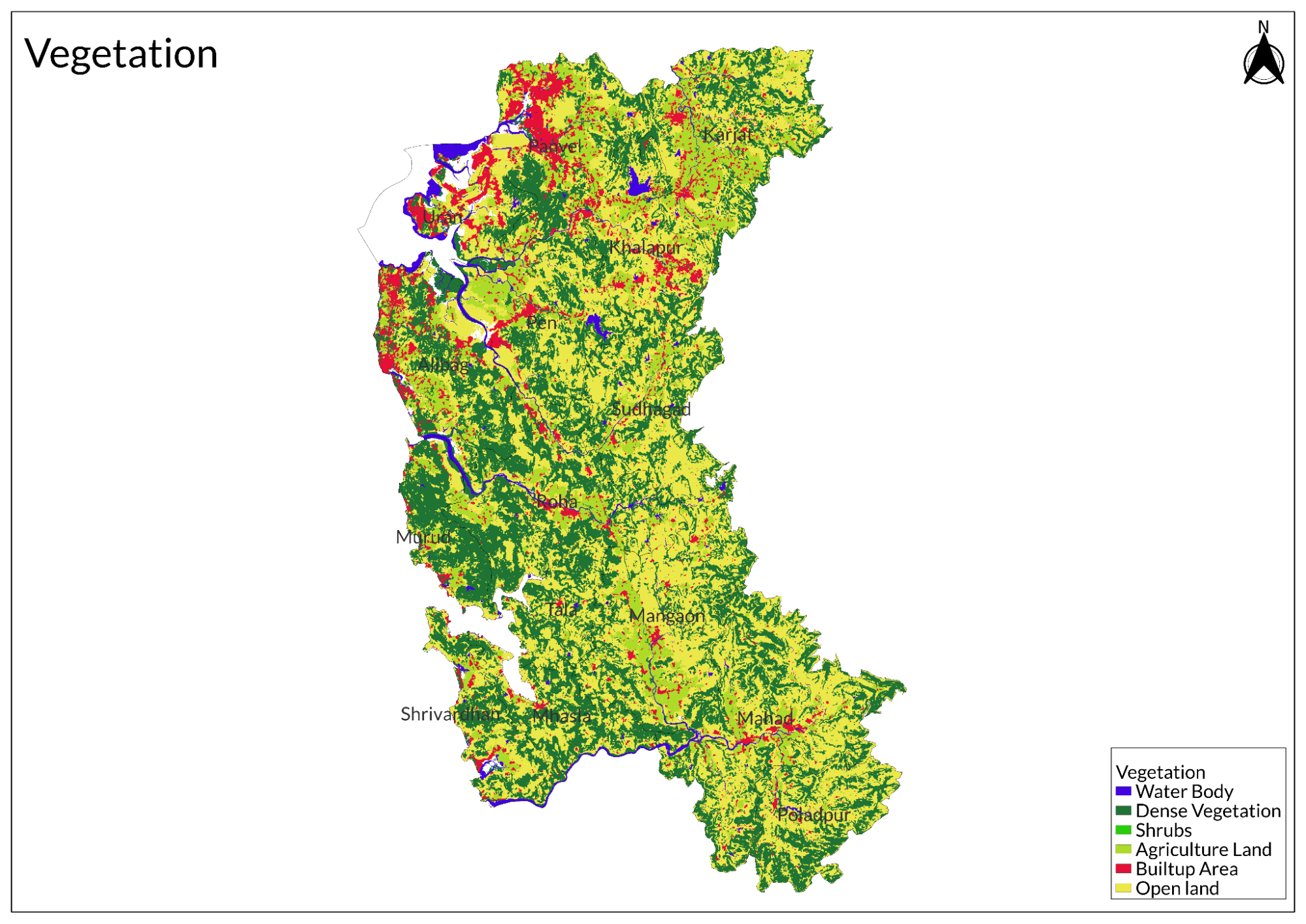

The Western Ghats section of Raigad features predominant tree species like Anjani, Jambul, and Ain. The semi-evergreen forests also contain Kinjal, Behda, and numerous medicinal plants.

The coastal belt is dominated by mangrove species, including Avicennia and Sonneratia, particularly in creek areas of Alibag, Murud, and Shrivardhan. Behind the mangrove zones, beach vegetation includes Ipomoea and Spinifex. The coastal plateaus support specialized flora adapted to lateritic conditions, including seasonal herbs and grasses. Agricultural landscapes feature traditional varieties of rice in the lowlands, while coconut, betel nut, and mango dominate the plantation sectors.

The central region's riparian zones house species like Umbar and Vad along river courses. The plateaus contain drought-resistant species such as Bibba and Palas. Economically important species like Ain and Kinjal are found in protected forest patches, while sacred groves preserve rare species, including some endemic orchids and medicinal plants.

Wild Animals

Other notable carnivores include the Indian Fox, Jungle Cat, and Golden Jackal. Among primates, the district hosts substantial populations of Hanuman Langur and Bonnet Macaque.

Wild Boar are common throughout the district, while Indian Muntjac or Barking Deer can be found in the denser forest patches. The forest floor supports various species of rodents including the Indian Porcupine and Indian Hare. The district also harbors several species of civets, including the Small Indian Civet and Common Palm Civet.

Birds

The coastal regions, particularly around Alibag and Murud, host numerous seabirds and waders. Common coastal species include Lesser Sand Plover, Little Egret, Grey Heron, and various species of gulls and terns. The mangrove ecosystems support specialized birds like the Striated Heron, Common Sandpiper, and Collared Kingfisher.

The Western Ghats section of the district harbors forest specialists, including the Malabar Grey Hornbill, Heart-spotted Woodpecker, and various flycatchers. The renowned Malabar Whistling Thrush is found in dense forest patches, while raptors like the Crested Serpent Eagle and Black Kite dominate the skies. The grasslands and agricultural areas support ground birds such as Red-wattled Lapwing, Yellow-wattled Lapwing, and various species of larks and pipits.

The district's wetlands and river systems attract numerous migratory birds during winter. Species like the Northern Pintail, Garganey, and Common Teal visit these water bodies seasonally. The Phansad Wildlife Sanctuary is particularly notable for birds like the Indian Pitta, Paradise Flycatcher, and various species of sunbirds and flowerpeckers. Urban and semi-urban areas support adaptable species like House Crow, Common Myna, Red-vented Bulbul, and various species of swifts and swallows.

Forest Reserves

Karnala Bird Sanctuary

Karnala Bird Sanctuary, established as Maharashtra's first bird sanctuary, occupies 12.11 square kilometers in Panvel Taluka of Raigad district. This sanctuary, centered around the historic Karnala Fort, is a vital conservation site hosting 222 bird species, including 161 resident species, 46 winter migrants, 3 breeding migrants, 7 passage migrants, and 5 vagrant species. The sanctuary's significance is highlighted by the presence of eight Western Ghats endemic species, including the Grey-fronted Green-pigeon, Nilgiri Woodpigeon, Malabar Parakeet, and Malabar Grey Hornbill. It's particularly notable for rare bird sightings such as the ashy minivet, three-toed kingfisher, Malabar trogon, Slaty-legged Crake, and Rufous-bellied Eagle. Beyond avian diversity, the sanctuary supports 114 butterfly species and occasional leopard sightings, making it an essential ecosystem within the North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests. Its strategic location near Mumbai and accessibility via the Mumbai-Pune highway have made it a popular destination for bird-watchers and conservationists, while its status as an Important Bird Area (IBA) underscores its role in biodiversity conservation.

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Illegal Mining and Deforestation

Mining activities in Raigad district, particularly illegal sand mining, have caused severe environmental degradation, including soil erosion, shoreline damage, and tree loss. These operations threaten beaches, water security, and climate stability, while the destruction of mangroves and mudflats for port terminals has further damaged local ecosystems. Construction-related dust emissions have worsened air pollution, posing health risks to residents.

The rise in landslides in the region stems from mining operations, deforestation, and extreme heat conditions, with open-pit mining particularly destructive to landscapes and water quality. Following a deadly landslide in Irshalwadi, environmentalists have demanded an immediate ban on all mining activities, arguing that high-intensity blasting loosens hillside soil and increases landslide risks. They've called for comprehensive assessments of soil conditions and mining's ecological impact to prevent further disasters.

Coastal Erosion

Coastal erosion in Raigad district, Maharashtra, has reached alarming levels according to a study by the Srushti Conservation Foundation that used satellite imagery to document approximately 55 hectares of coastal area near Devghar (equivalent to ten times the size of Mumbai's Wankhede Stadium) being submerged between 1990 and 2022. The research, focused on the Bankot Creek mouth area, revealed a shoreline retreat of nearly 300-500 meters inland, with significant loss of mangroves, mudflats, and sandy coasts, while climate change and rising sea levels continue to accelerate this erosion. SCF Managing Director Deepak Apte criticized current practices like kharland bunds as counterproductive, destroying natural barriers and facilitating further erosion rather than protecting the coastline.

The study documented struggling mangrove and Casuarina plantations that have been unable to withstand sediment loss, resulting in widespread uprooting and degradation, with satellite images showing uneven mangrove distribution and large patches of dead vegetation. Extreme weather events have compounded these problems, as evidenced by Cyclone Nisarga in 2020, which caused substantial damage to local vegetation and killed numerous mangrove species. While some areas show signs of recovery, large tracts remain vulnerable due to changing sediment composition from muddy to sandy, highlighting the urgent need for systematic assessment and development of long-term strategies to protect Maharashtra's coastline from further degradation.

Industrial Pollution

Pollution in Raigad district, Maharashtra, has become a critical environmental issue, with a recent report identifying 1,219 industrial units classified as "most polluting," primarily consisting of manufacturing plants, chemical facilities, and heavy industries that release harmful pollutants into the air, water, and soil. These industrial operations have significantly degraded air quality and posed serious health risks to nearby communities, while their effluents have contaminated local water bodies, threatening aquatic biodiversity, compromising the livelihoods of fishing and agricultural communities, and raising substantial concerns about the safety of drinking water supplies and overall public health in the region.

Waste Management

Waste management in Raigad district, Maharashtra, faces substantial challenges, with environmental activists disputing official claims of effective systems, particularly in rural areas and tourist hotspots like Kashid beach, where the presence of approximately 75 hotels and numerous shacks generates over 300 metric tonnes of waste that is often improperly disposed of through burning. Reports of illegal dumping and waste burning have emerged in locations such as Palaspe near the Mumbai-Goa highway, where garbage accumulation leads to problematic air pollution when set ablaze, while activist Prashant Vogety emphasizes that despite the existence of rural solid waste management policies on paper, implementation remains inadequate, with complaints about waste burning prompting some intervention from zilla parishad officials but failing to completely address the issue as smoke continues to be observed, especially during early morning hours, and similar disposal problems persist in other tourist destinations including Revdanda and Kurul.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Protests against industrial projects in Raigad district, Maharashtra, have gained significant momentum as local communities express their concerns over environmental and social impacts. One of the most notable projects inciting opposition is the Dighi Port Project, where farmers from 78 villages have voiced strong objections due to fears of forced land acquisition and the loss of agricultural land and resources.

Another contentious area is the Lote Parshuman industrial belt in Chiplun, which has been linked to chemical pollution affecting both air quality and local rivers. Residents are increasingly worried about the health implications and environmental degradation associated with industrial activities in this region.

The NAINA policy has also sparked considerable unrest, with around 4,000 villagers marching from Panvel to Mantralaya to protest against the policy. They argue that it threatens their livelihoods and access to land without adequate compensation or public consultation.

Mangrove Conservation

Mangrove conservation in Raigad district, Maharashtra, has become a priority with approximately 21,000 hectares of mangrove forests serving as natural barriers against climate change impacts like rising tides, cyclones, and erratic monsoons, while also functioning as carbon sinks. A key initiative in this effort is the partnership between Apple and the Applied Environmental Research Foundation (AERF), which focuses on creating sustainable economic opportunities for local communities through conservation agreements with villages affected by saltwater intrusion and agricultural land loss, helping residents like Namdev Waitaram More recognize how mangroves protect their paddy fields from saltwater damage.

The conservation program addresses challenges faced by communities whose traditional farming practices have been disrupted by seawater encroachment, with AERF providing education about mangrove importance and training for sustainable practices that develop alternative livelihoods without relying on cutting mangroves for firewood. These efforts have empowered community members to engage in sustainable fishing and crab hunting while promoting the collection of fallen branches rather than harvesting live trees, with recent extreme weather events like cyclones reinforcing local awareness about the crucial protective role mangroves play in safeguarding coastal communities from natural disasters.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Matheran: Asia’s Only Automobile-Free Hill Station

In Raigad district, Matheran, a hill station in Karjat taluka, bans automobiles, preserving its calm and clean environment. Past Dasturi Naka, where vehicles stop, only a municipal ambulance and 20 eco-friendly e-rickshaws, permitted by the Supreme Court in 2022 for trials, operate. Declared an eco-sensitive zone in 2003, Matheran protects its forests and red laterite hills from pollution and mining. Plastic bans and regular cleanups maintain its pristine state.

Travel within Matheran relies on over 90 hand-pulled rickshaws, about five hundred ponies, or walking. Porters, including women, navigate forest shortcuts to carry supplies. Packhorses deliver essentials like groceries and medicines. Unpaved red laterite paths evoke a rustic charm, like Bhilar’s literary village or Beed’s rugged terrain. E-rickshaws, restricted to current rickshaw pullers, aim to ease labor while safeguarding ecology. Locals hold mixed views on their impact.

The Matheran Hill Railway, a narrow-gauge toy train, seeks UNESCO World Heritage status. Spanning 21 km from Neral to Matheran, it winds through forests, offering views of waterfalls and valleys. Built between 1904 and 1907 CE, it stops at Jummapatti, Waterpipe, and Aman Lodge, partly using solar and wind power. The 2.5-hour journey pauses during monsoons due to landslides, as seen from 2016 to 2019. An hourly Aman Lodge-Matheran shuttle carries 85 passengers.

Sources

Bose, M. 2023, July 20. Irshalwadi wake up call; ban mining of Raigad, Thane hills: Environmentalists. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com//india/irshalwa…

Brief Industrial Profile of Raigad District. MSME-Development Institute, Ministry of MSME Govt. of India.https://dcmsme.gov.in/old/dips/raigad_final.…

Chatterjee, B. 2017, March 31. Illegal sand mining continues in Raigad district. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/i…

Conserving mangroves to protect local livelihoods and the planet. 2022, April 21. Apple Newsroom (India).https://www.apple.com/in/newsroom/2022/04/co…

District Planning Map Series, National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organisation. 1999. Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.https://surveyofindia.gov.in/files/RAIGARH_1…

Home—Raigarh District. 2025, March 6. Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency; Government of Maharashtra, Water Supply and Sanitation Department..https://gsda.maharashtra.gov.in/raigad-distr…

Kumar, S. 2023, December 19. 1,219 industrial units categorised as most polluting in Raigad. Outlook Business.https://www.outlookbusiness.com//news/1-219-…

Raigad, India weather in July. 2025. Wanderlog.https://wanderlog.com/weather/1183/7/raigad-…

Singh, V. 2024, January 28. Waste management in Raigad villages going up in smoke, say greens. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/waste-ma…

Team 30 Stades. 2022. “Matheran: Asia’s Only Automobile-Free Hill Station.” 30 Stades.https://30stades.com/2022/07/10/matheran-asi…

Tembhekar, C. 2022, September 16. Climate change: 55 ha coastal area in Raigad submerged, finds study. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mum…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.