Contents

- History

- The Bhor Ghat Route & the Mumbai–Pune Expressway

- CIDCO & Navi Mumbai

- Atal Setu

- Modes of Transport

- Railway Systems

- Ferries & Water Transport

- Overview of Bus Networks

- Metro Services

- Autos & Shared Vehicles

- Air Travel

- Traffic Map

- Communication Networks

- Newspapers & Magazines

- Cable News Channels

- Graphs

- Road Safety and Violationse

- A. Cases of Road Safety Violations

- B. Fines Collected from Road Safety Violations

- C. Vehicles involved in Road Accidents

- D. Age Groups of People Involved in Road Accidents

- E. Reported Road Accidents

- F. Type of Road Accidents

- G. Reported Injuries and Fatalities due to Road Accidents

- H. Injuries and Deaths by Type of Road

- I. Reported Road Accidents by Month

- J. Injuries and Deaths from Road Accidents (Time of Day)

- Transport Infrastructure

- A. Household Access to Transportation Assets

- B. Length of Roads

- C. Material of Roads

- Bus Transport

- A. Number of Buses

- B. Number of Bus Routes

- C. Length of Bus Routes

- D. Average Length of Bus Routes

- E. Daily Average Number of Passengers on Buses

- F. Revenue from Transportation

- G. Average Earnings per Passenger

- Communication and Media

- A. Household Access to Communication Assets

- B. Newspaper and Magazines Published

- C. Composition of Publication Frequencies

- Sources

RAIGAD

Transport & Communication

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

In Raigad district, its transport and communication links have long grown from old coastal ports and ancient inland routes that connected the Konkan coast with the Deccan. Historic centres such as Chaul and Panvel moved goods by sea, bullock cart, and early mountain passes through the Sahyadris, laying the groundwork for the region’s links long before modern rail, roads, and ferries tied it more closely to Mumbai and Pune. Over time, the district has witnessed significant infrastructure development to support both intra-city movement and regional connectivity. It is connected by rail, bus, ferries, auto-rickshaw, and air travel, with the availability and reach of these systems offering a glimpse into its evolving landscape.

History

Transportation networks have always been essential to human civilization, as they connect distant regions and support the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. They have shaped economies, and they have helped communities grow through trade and communication. For centuries, Raigad (formerly known as Kolaba) has owed much of its prosperity to its position along important trade routes connecting the coastal Konkan with the Deccan plateau. The district’s ancient ports: Chaul (refer to Political History for more), foremost among them, were once busy centres of maritime trade.

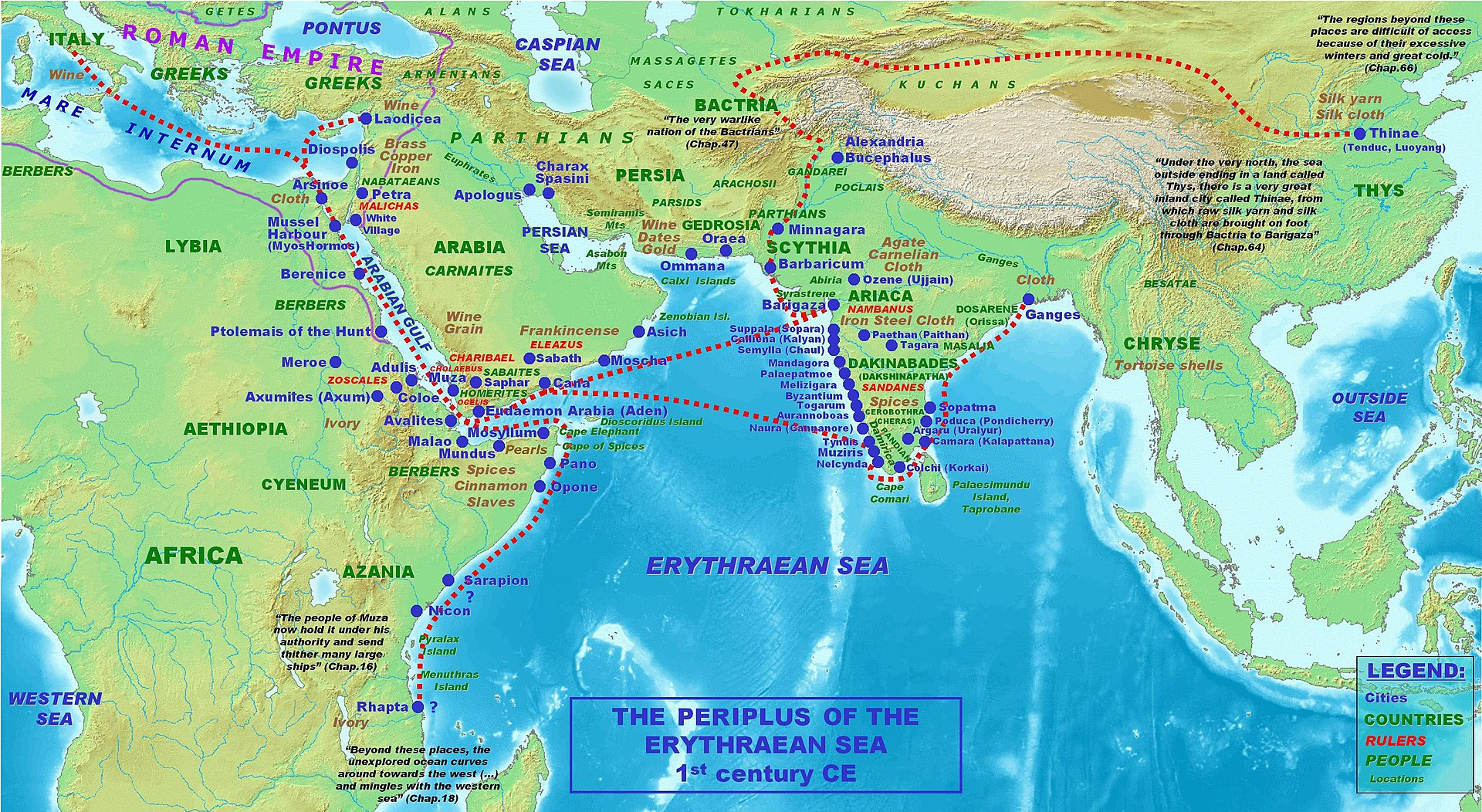

References to Chaul appear in some of the oldest geographical records: Ptolemy’s Geographia (2nd century CE) mentions it as Symulla, and the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (3rd century CE) describes it as a notable harbour. Inscriptions from the Kanheri Caves at Borivali (Mumbai Suburban district) reveal that local merchant communities and Buddhist monasteries helped maintain these trade routes.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a merchant, in the 6th century, knew it as Sibor; the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang), in the 7th century, called it Chimolo, remarking upon riches brought by the sea.

When Athanasius Nikitin, the Russian traveller, passed this way in 1470, he found the town, which he named Chivli, a curious mix of opulence and rustic simplicity. Duarte Barbosa, a Portuguese writer and officer, visiting in 1514, described it as a small place by the monsoon, but in winter transformed: traders flocked in, stalls lined the roads for miles, and goods arrived by endless trains of oxen, linking Chaul to Surat, Goa, the Persian Gulf, and Arabia.

It is mentioned in the Kolaba district Gazetteer (1883) that the trade here was ancient and far-reaching: pearls, rice, spices, silks, metals, ornaments, and drugs found passage through Chaul’s docks. In return came wines, fine textiles, coins of gold and silver, brass, copper, and luxuries of the age. Even slaves, sadly, were counted among its commodities. Trade ties reached west to the Red Sea and Egypt, and inland along the passes that pierced the Sahyadris.

The district’s importance rested not just on its coastline but also on its mountain passes. Bhor Ghat (near Khopoli), Shevate Ghat (in Mahad taluka), and Madhe Ghat (near Pune) were ancient links between the Konkan coast and the Deccan. They have been in use since at least the 3rd century BCE. These passes allowed goods, rice, oil, spices, metals, and textiles to move inland and outward to distant ports.

Besides Chaul, Goregaon (historically called Ghodegaon) near the Kal River was also an important inland trade point. It is believed by some to be the Hippokura of Ptolemy’s map. Its riverine location supported commerce well into later centuries (refer to Political History for more).

Likewise, the town of Pen, with its port at Antora (refer to Political History for more), finds mention as early as the Silahara rule (9th–12th centuries) and later under the Yadavas. A place of easy passage between the coast and Bombay by the Bor Pass, Pen thrived on its salt pans and rice trade. In the early 19th century, boats of seven tons could dock at Antora’s tide, and larger craft at the spring tides, ferrying goods as far as Egypt and inland to the Deccan.

It is recorded in the Kolaba Gazetteer (1883) with precision the web of early roads and passes that sustained this trade. By 1826, three principal routes linked Poona to Kolaba: through Save Pass, Bor Pass, and Unhere; from Poona to Ratnagiri via Sevtya Pass and the Savitri River; and two roads to Ghodegaon by Devsthali Pass and Siroli. Dasgaon on the Savitri boasted further branches north to Nagothna and south to Khed, binding river and road alike into a system of ceaseless movement. Together, these coastal ports and mountain passes made Raigad a vital link between India’s interior and the wider trading world.

The Bhor Ghat Route & the Mumbai–Pune Expressway

For centuries, movement between Mumbai (then Bombay) and Pune (Poona) relied on a mix of sea routes and rugged inland paths crossing the Western Ghats. Before modern highways and railways, the coastal stretch from Mumbai to Panvel or Uran and the Bhor Ghat inland pass (which is briefly mentioned above) together formed the backbone of this route.

In the late 18th century, the strategic importance of this corridor became clear during the First Anglo-Maratha War. It is noted in historical records that to secure their stronghold in Mumbai and expand inland, the British needed a dependable connection to Pune, the seat of the Maratha Empire under the Peshwas. At that time, it is said that the Bhor Ghat was little more than a narrow forest track, suitable for lone horsemen or foot soldiers but impractical for moving large British columns and heavy artillery.

The Battle of Wadgaon in 1779 highlighted this weakness. Maratha forces under Nana Fadnavis blocked British advances by using the dense ghat terrain to their advantage, forcing the British to surrender large territories. This defeat demonstrated that any future military campaign would need a road capable of supporting troop movements and supply lines through the Ghats.

Following renewed conflict during the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1802–1803), Peshwa Bajirao II, seeking British support after his defeat by rival Maratha chiefs, signed the Treaty of Bassein. Under General Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington), the British defeated the Maratha confederacies and took control of Pune. With control secured, the British began improving the Bhor Ghat trail into a usable military road. By 1804, the first proper roadwork allowed horses and carts to pass with greater ease.

During this period, the sea route remained vital. Travelers, traders, and mail often sailed from Bombay to landing points such as Panvel, Uran, or Ulwa. From these coastal nodes, they continued inland on foot, horseback, or by bullock cart via the ghat passes. Small ferries and boats provided the link across creeks and shallow harbours, forming the maritime leg of the journey.

Improvements continued over the next decades. By 1830, under Governor Sir John Malcolm, the road was upgraded to handle horse-drawn carriages. The postal department introduced Dak Bungalows (rest houses and staging posts for palanquin bearers and mail runners), helping travelers complete the journey more comfortably. Travel time from Bombay to Poona, which once took about a week by foot and boat, was reduced to three or four days by carriage.

In 1863, the opening of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway’s line through the Bhor Ghat drastically shortened travel time further, but the road remained important for local transport, military logistics, and postal services. Ferries between points like Ulwa and Bhaucha Dhakka (Mazgaon Docks) continued to operate into the 20th century, supporting coastal trade and passenger movement alongside the inland road.

By the early 20th century, the original ghat road evolved into the old Bombay–Poona Highway (NH 4, now NH 48). This route closely followed the alignment laid down under Wellesley’s early plans. The path, once just a trekking track under dense forest cover, grew into one of India’s busiest intercity highways, forming a crucial corridor for people and goods moving between Mumbai, Pune, and the wider Deccan. Interestingly, today, the modern Mumbai–Pune Expressway, opened in the early 2000s, runs roughly parallel to this historic route.

CIDCO & Navi Mumbai

The district saw another phase of major development with the rise of Navi Mumbai, planned by CIDCO in the 1970s. In 1975, plans were made to connect Navi Mumbai to Mumbai via a new over-bridge across the Vashi Creek, improving road access to the mainland. This made it easier for residents from Raigad’s coastal belt and new urban nodes to reach Mumbai or Thane directly via the Panvel Bus Depot, which became a regional hub.

Atal Setu

In January 2024, the Mumbai Trans Harbour Link, also called Atal Setu, was inaugurated. This bridge connects Chirle village in Uran taluka with Sewri in Mumbai and is the longest sea bridge in India. It is intended to reduce travel time between Mumbai and Pune by about 30 minutes.

Modes of Transport

Railway Systems

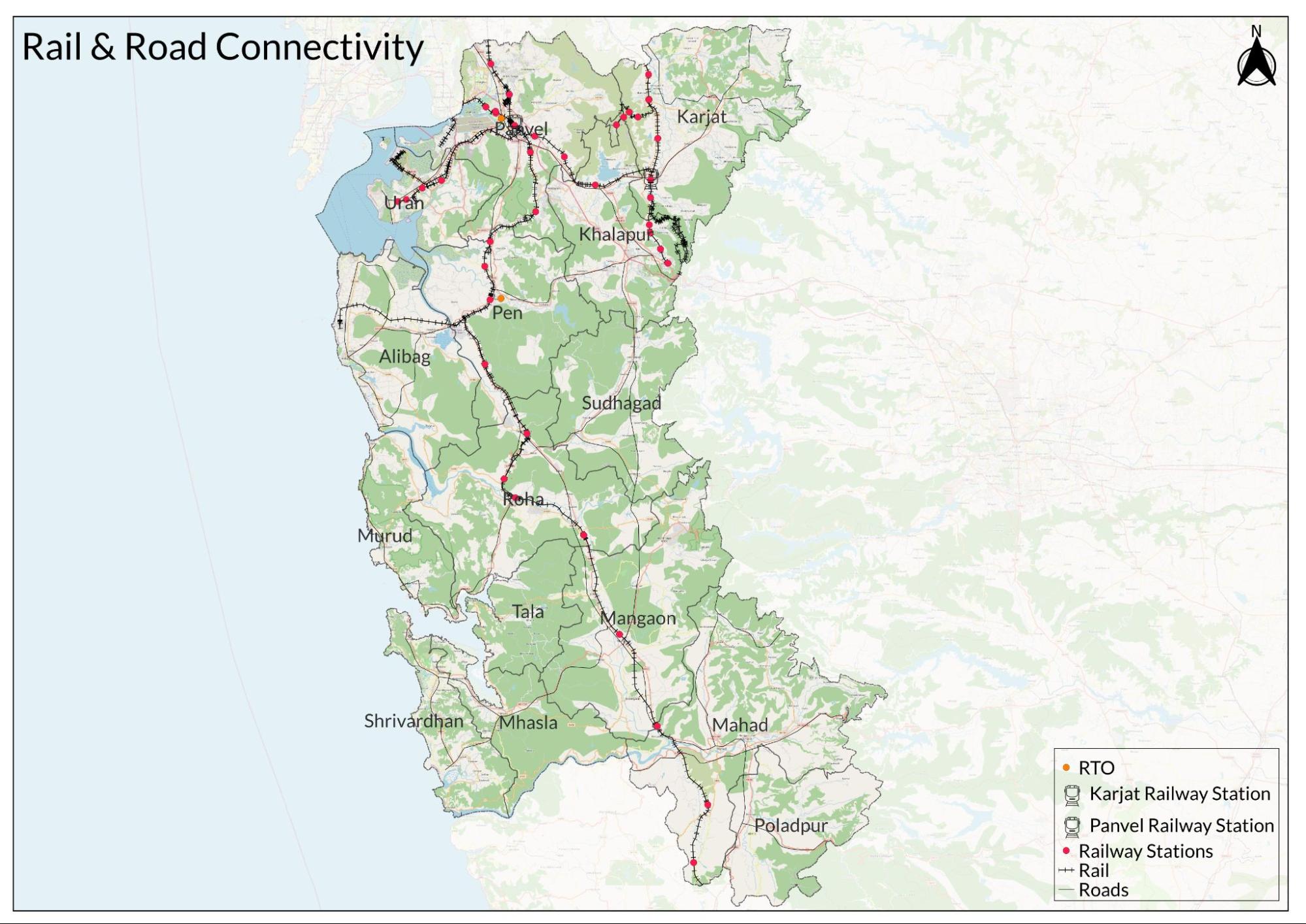

Raigad district’s railway network falls mainly under Central Railway, managed through its Mumbai Division, with part of its southern section connected by Konkan Railway Corporation Limited (KRCL). Major nodes include Panvel, Karjat, Khopoli, Roha, Pen, and the developing Uran corridor. Together, these routes handle suburban services, long-distance trains, freight for ports, and industrial movement.

Panvel is the district’s principal junction. It links the Harbour Line suburban network with the main line through Diva, the Panvel–Karjat corridor, and the Roha section that feeds into the Konkan Railway. Karjat is a junction at the base of the Bhor Ghat on the Mumbai–Pune main line, while Khopoli branches off from Karjat, serving industries that rely on hydroelectric power and local freight.

The first railway to reach the district came with the expansion of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which began operating in 1853 and soon pushed east through the Bhor Ghat to link Mumbai with Pune (see Transport & Communication of Pune for more). This steep stretch of track made Karjat an important stop at the base of the incline, where trains gathered momentum for the climb or prepared for the descent into the Konkan plains. A short branch line extended from Karjat to Khopoli, supporting new industrial sites that depended on steady freight links, including hydroelectric works and early mills.

Along this early rail corridor, smaller stations such as Palasdhari, Kelavli, Dolavli, and Lowjee handled both local passengers and outgoing loads of timber, rice, paper, or charcoal bound for the Bombay market. For nearby villages, these stops offered new access to the wider region.

As rail services grew, they also changed older trade routes that had once depended on carts, pack animals, and small ports. Remarkably, it is noted in the Kolaba district Gazetteer (1883) that “Pen is said to have suffered by the opening of the railway between Poona and Bombay. Before the opening of the railway, many exports from the Deccan came to Pen as a port and trade centre; now all go straight to Bombay or Panvel.” For Pen, which had once thrived as a coastal trading point, the railway marked the beginning of decline as goods and merchants switched to faster inland lines.

While the GIPR trunk line and its early branches reached Karjat and Khopoli, large parts of the district further south and west remained unconnected. In the late 19th century, local authorities and planners began suggesting new inland links to revive trade between coastal and interior markets. One idea mentioned in the Gazetteer (1883) was a rail line from Kalyan to Mahad, with stops at Taloja, Panvel, Apta, Pen, Nagothane, Kolad, Mangaon, and other small marts. At the time, this plan promised to open rice-growing belts and salt pans deeper in the Konkan, but the idea remained on paper for decades and would not take shape until much later.

In 1907, Adamji Pirbhoy constructed the narrow-gauge track from Neral up to Matheran, a small hill station that drew visitors looking for cooler air above the Konkan’s humid coast. The tight curves and forested slopes of the Matheran Hill Light Railway made it a rare branch that served more leisure than freight, running seasonal rail motors through thick woods and scenic ridges. Operated under Central Railway today, the line remains one of the few hill railways still in use, mostly carrying tourists.

While the idea of new inland routes lay dormant for decades, it was only after Independence that plans to extend the railway deeper into Raigad began to take shape. By the early 1960s, the region’s ports, rice belts, and growing industrial areas needed better links to Mumbai’s market and harbour. This revived the old ambition of connecting the coastal belt to the main line.

A plan for a new broad-gauge track from Diva to Panvel was approved in 1961. Work started in 1962, and by the end of 1964, goods wagons were already moving along the line. This gave Panvel its first direct link back to the city, which it would soon outgrow to become a junction in its own right.

In its early years, the new track mainly carried freight: rice, salt, timber, and port cargo. To meet local demand, mixed trains began running with a few passenger coaches added to goods wagons. Within a few seasons, a direct passenger link between Panvel and Mumbai was in place, a small but steady start to the daily traffic that now defines the route.

Following the main stretch, new branches were added to serve smaller ports and interior markets. The Panvel–Uran line, opened in 1966, aimed to handle coastal cargo and later supported the Jawaharlal Nehru Port’s early freight needs. Around the same time, the Panvel–Apta section was laid to open up paddy fields and rice mills further inland, connecting them to larger buyers by rail.

By the early 1980s, the track extended deeper. The stretch from Apta to Pen opened in 1983, reconnecting Pen to a new form of trade after its coastal route had declined a century earlier. The final link to Roha, completed in 1986, stitched together what earlier planners had only sketched as the Kalyan–Mahad corridor.

By the late 1980s, the railway through Panvel had grown from a single goods line into a vital link for both freight and daily travel. Industries around Panvel, Uran, and the expanding nodes of Navi Mumbai depended on steady rail movement for raw materials and finished goods. As towns grew, so did the number of daily passengers using local trains to reach Bombay’s markets, ports, and offices.

To keep up with this growth, new connections were added. The Panvel–Karjat line, planned in the early 1990s, was meant to ease east–west travel across the district and give Panvel a direct route into the Deccan without passing through the busy Bhor Ghat main line. Work on the line began in 1993 and continued into the early 2000s, opening a second corridor for goods wagons and local passengers moving between Raigad’s plains and Pune’s uplands.

At the same time, the suburban network tied Panvel more closely to Mumbai’s daily commuter belt. Local services on the Harbour Line connected Panvel with Mumbai and Thane, feeding thousands of passengers in and out each day. By the early 2000s, regular Harbour Line trains became the backbone of travel for workers and small traders moving between the district and the city. A direct train link between Panvel and Goregaon, added in 2020, gave commuters better access to the western suburbs as well.

Despite these upgrades, locals say that most local trains remain slow services, with stops at nearly every station along the way. Travel from Panvel to the city can still take up to two hours during peak times, but fares stay low enough to keep trains the main option for daily movement.

One place the railway has never reached is Alibag. Although it remains one of the district’s busiest coastal centres, its steep coastal terrain and well-used road network have kept rail expansion at bay. Instead, the old ferry crossing to Bombay has held its place as the main link across the water.

Ferries & Water Transport

Before the railway network was established, water routes were the main means of transport in Raigad. Common routes connected Mumbai with Revas (near Alibag), Dharamtar with Revas and Mumbai, Dharamtar with Nagothane, and Panvel with Ulwa and Mumbai harbour. Local vessels such as the Bambot, Padav, Machva, Dharan, Mhangiri, Phatemari, Kothiya, and Batelo carried grain, salt, timber, and passengers. In 1570, Panvel port was recorded as a point of export for food grains, salt, grass, and wood to European traders.

When rail and road connections expanded, smaller ports declined due to a lack of use and maintenance. In 1966, the Maharashtra Maritime Board was formed to revive neglected sites and listed 42 ports for improvement, including Panvel.

In many parts of the district, locals recall that small boats were used to cross creeks and rivers until the late 20th century. Bridges and roads have replaced most of these crossings. Ferries continue to operate on the Mandwa–Mumbai route and at Belapur Jetty. A one-way fare from Mandwa is about ₹300. From Belapur, boats run to Gharapuri Island (Elephanta Caves), with a return fare of about ₹700.

Overview of Bus Networks

Bus services in Raigad district connect towns, taluka centres, and villages with each other and with larger urban areas in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. The public network is strongest around Panvel and Khopoli, which serve as major road transport nodes for the northern part of the district. Within the Panvel Municipal Corporation area, services are operated by agencies such as Navi Mumbai Municipal Transport (NMMT), Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport (BEST), Thane Municipal Transport (TMT), Kalyan Dombivli Municipal Transport (KDMT), and Khopoli Municipal Transport (KMT). These buses link Panvel and Kharghar with parts of Navi Mumbai and neighbouring cities such as Thane and Kalyan, and act as feeders for railway stations like Panvel, Khopoli, and Karjat.

Panvel’s main bus stand handles State Transport (ST) buses along with municipal buses. A separate NMMT depot supports daily city and intercity services. The Maharashtra State Road Transport Corporation (MSRTC) remains the main provider of bus connections for most villages and small towns, covering routes to Alibag, Pen, Roha, Mangaon, Mahad, and interior settlements. ST buses are the main form of public transport in areas outside the municipal limits, where rail links are limited or absent.

In recent years, AC electric buses have been introduced on routes connecting Panvel with Mumbai and Thane. Private shuttle services also operate from Panvel and Kharghar to city offices, used mainly by daily commuters. In Khopoli and Karjat, many residents rely on buses to reach workplaces in Mumbai or Navi Mumbai, especially where train services are less frequent. In 2011, NMMT added a bus route connecting Kopar Khairane to Khopoli to widen options for commuters in that part of the district.

In most other Raigad talukas, ST buses remain the primary means of public transport. Khopoli continues to be an important road transport hub for buses running southwards towards Pali and other interior points.

When it comes to its history, fascinatingly, locals recall that organised bus services in the district first began through private efforts in the early 1900s. In 1913, Vishnu Krushnashastri Puranik started a service between Panvel and Mumbra, and others soon followed. Operators such as Mohanshet, Sorabjishet, and Mamdumia Patel ran routes from Panvel to Mumbra and Mumbai. By the 1920s, new connections linked Panvel to Karjat, Khopoli, Pen, and Pune. Early routes were run by residents like Isakshet, Vishnu Khot, Bhau Natu, and Tatya Padhyay, with tickets sold from Kantishet Banthia’s shop in Panvel, which many older residents still mention as the starting point for early buses.

Before better roads and bridges, passengers combined these early bus trips with ferry crossings and horse carts to complete longer journeys within the district.

Metro Services

Metro services in Raigad district operate only in Panvel taluka as part of the Navi Mumbai Metro network. The main line starts at Taloja and passes through stations such as Panchnand, Pathpada, Central Park, Kharghar Gaon, Kharghar Vihar, Utsav Chowk, Belpada, and RBI Colony. Metro Line 2 connects MIDC Taloja to Khandeshwar over about 7 km, while Metro Line 3 links Pendhar to MIDC Taloja over nearly 4 km. A future Metro Line 4 has been planned to run from the Navi Mumbai International Airport to Panvel, covering about 4 km.

These metro routes supplement the suburban railway in the same area. Stations such as Khandeshwar, Mansarovar, and Kharghar on the Thane–Vashi–Panvel corridor provide daily local and regional connections through Panvel station.

Autos & Shared Vehicles

Short-distance travel in Raigad is mainly covered by auto rickshaws and six-seater vans known locally as Tum-Tums. These vehicles usually run on fixed local routes and are operated by local drivers, often small farmers who use the service as a second source of income. Tum-Tums typically carry 7 to 8 passengers and charge between ₹15 and ₹30 per person, depending on distance.

Traditional taxis (called Kaali-Peeli) and app-based ride services such as Ola, Uber, and Rapido also operate in parts of the district, especially in Panvel and Kharghar. These services are mainly used for longer trips to Mumbai, Thane, and Navi Mumbai. When booked from Mumbai or Thane to towns like Pen, Khopoli, or Karjat, these routes are generally treated as outstation trips in app-based systems.

Air Travel

Air travel in the district will be served by the D. B. Patil International Airport, currently under construction at Ulwe in Uran taluka. Once operational, it is expected to improve passenger and cargo connectivity for Raigad and surrounding areas.

Traffic Map

Communication Networks

Newspapers & Magazines

Raigad district has a long record of local newspaper and magazine publishing that reflects its active cultural and social life. By the late 19th century, Alibag was known for several Marathi weeklies and monthlies. Satya Sadan (Home of Truth) began in 1870 as a weekly release every Saturday for an annual fee of Rs. 1. Sharabh (Grasshopper) was launched in April 1882, published every Wednesday, also at Rs. 1 per year. Satdharma Dip (Light of True Religion) started in 1878 and appeared on the first day of each Hindu month at Rs. 1.25 annually. Abala Mitra (Woman’s Friend) was first issued in 1879 as a monthly at Rs. 1.50 per year. These titles indicate an early readership interested in social issues, religion, and women’s matters.

In Panvel, interestingly, when it comes to the media landscape, locals say that one early record dates to 10 November 1872, when Krushnashashtri Puranik placed an advertisement for his medicines in the magazine Arunoday. Later, locals say that in 1895–96, Prabodhankar Thakre, while at school in Panvel’s Bapat Wada, produced a weekly student paper distributed in limited copies.

Through the 20th century, new local newspapers were started across the district. Krushival, edited by S. S. Deshmukh in Veshavi, Alibag, is among the best-known titles. Colaba Darpan, edited by Satish Dharap, is also published by Veshavi. Colaba Shivtej, once edited by Adv. Vijaysinh Jadhav in Mahad, sold at 70 paise before closing. Kille Raigad, founded by L. P. Valekar on 19 February 1967 (Shivjayanti), maintains an online presence through a Facebook page.

Other papers include Kinarpatti (Sachin Pawar, Pen) and Vadalvara (Vijay Damodar Kadu, Uran), with Vadalvara expanding its reach through a YouTube channel. Further titles include Dainik Raigad Times (Subhash Pandit, Alibag), Sagar (Avishkar Desai, Alibag), Rasayni Times (Anil Ramesh Bhole, first published 5 May 1997), and Nirbhid Lekh (Kantilal Kadu, started 9 May 1997).

Cable News Channels

Cable television services began to expand in Panvel during the late 20th century, providing local access to news and community programming. Between 1981 and 1990, locals say Hemant Desai and R. K. Patil operated one of the first local cable channels, known as K.R.C. In 1992–93, Hemant Desai and Sashikala Desai launched Pan TV, which became known for covering local events and gained wider attention during the 2001 elections for its live updates and audience reach. The channel also started a dedicated news segment, Panvel Varta, which continued regular local news coverage.

In 2002, Abhay Vision began broadcasting and became locally known for its television serial Kadhi Kadhi Veglach Kahi Ghadta, which was described in local accounts as one of the few cable TV serials produced in India at the time that provided opportunities for local actors. Another channel, Karnal Aaj Tak, also operated in Panvel for some years before closing.

Graphs

Road Safety and Violationse

Transport Infrastructure

Bus Transport

Communication and Media

Sources

2011. NMMT connects city to Khopoli with new bus service. Mumbai Mirror. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/george-m…

Government of Maharashtra. 1964. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Kolaba District. Directorate of Printing and Stationery, Maharashtra State, Mumbai.

Heritage Directorate, Indian Railways. Making "Bombay–Poona" a Reality: Trains across Maharashtra's Bhor Ghat.Google Arts & Culture.https://artsandculture.google.com/story/maki…

James M. Campbell. 1883. Gazetteer Of The Bombay Presidency: Kolaba District. Vol 11. Government Central Press.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.201…

Kurush Dalal. 2019. Chaul: Maharashtra’s Medieval Port. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Panvel Municipal Corporation. 2024. Draft Revised & Comprehensive Development Plan for Panvel Municipal Corporation: 2024–2044. Panvel Municipal Corporation.https://panvelcorporation.com/public/map/PMC…

Sameera Kapoor Munshi. 2025. Panvel Station Redevelopment: Harbour Line Ticket Counter Relocated, New Facilities Unveiled. The Free Press Journal.https://www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai/panve…

Swachhandi. 2016. "भर पावसातला चांभारगड, शेवतचे घाट आणि उपांद्याचा घाट (Bhar Pavasatla Chambhar Gad, Shevatche Ghat ani Upandya Cha Ghat)." Maayboli.https://www.maayboli.com/node/59421

V. D. Veeragi. Glorious History of Pen. eChavdi.https://web.archive.org/web/20081227211902/h…

World Health Organization. Road Safety. WHO, Geneva.https://www.who.int/health-topics/road-safet…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.