Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Crustaceans (Crabs)

- Gubernatoriana thackerayi

- Forest Reserves

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Deforestation

- Coastal Erosion

- Water Scarcity

- Climate Change Vulnerability

- Mining

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Jaitapur Power Plant

- RRPCL Protests

- Bauxite Mining Project

- Turtle Conservation Efforts

- Environmental NGOs

- Apna Van Trust

- Konkan Nisarg Manch

- Mangrove Society of India (MSI)

- Nisarga Mitra Ratnagiri

- Ratnagiri Conservation Society

- Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra (SNM)

- Western Ghats Ecology Experts

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Soil Moisture (Yearly)

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- K. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- G. Relative Humidity

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

RATNAGIRI

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Ratnagiri district, located between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats, boasts a unique geography that results in a harmonious blend of lush forests, fertile agricultural land, and pristine beaches. Renowned for its iconic Alphonso mangoes, the region is rich in biodiversity and cultural heritage.

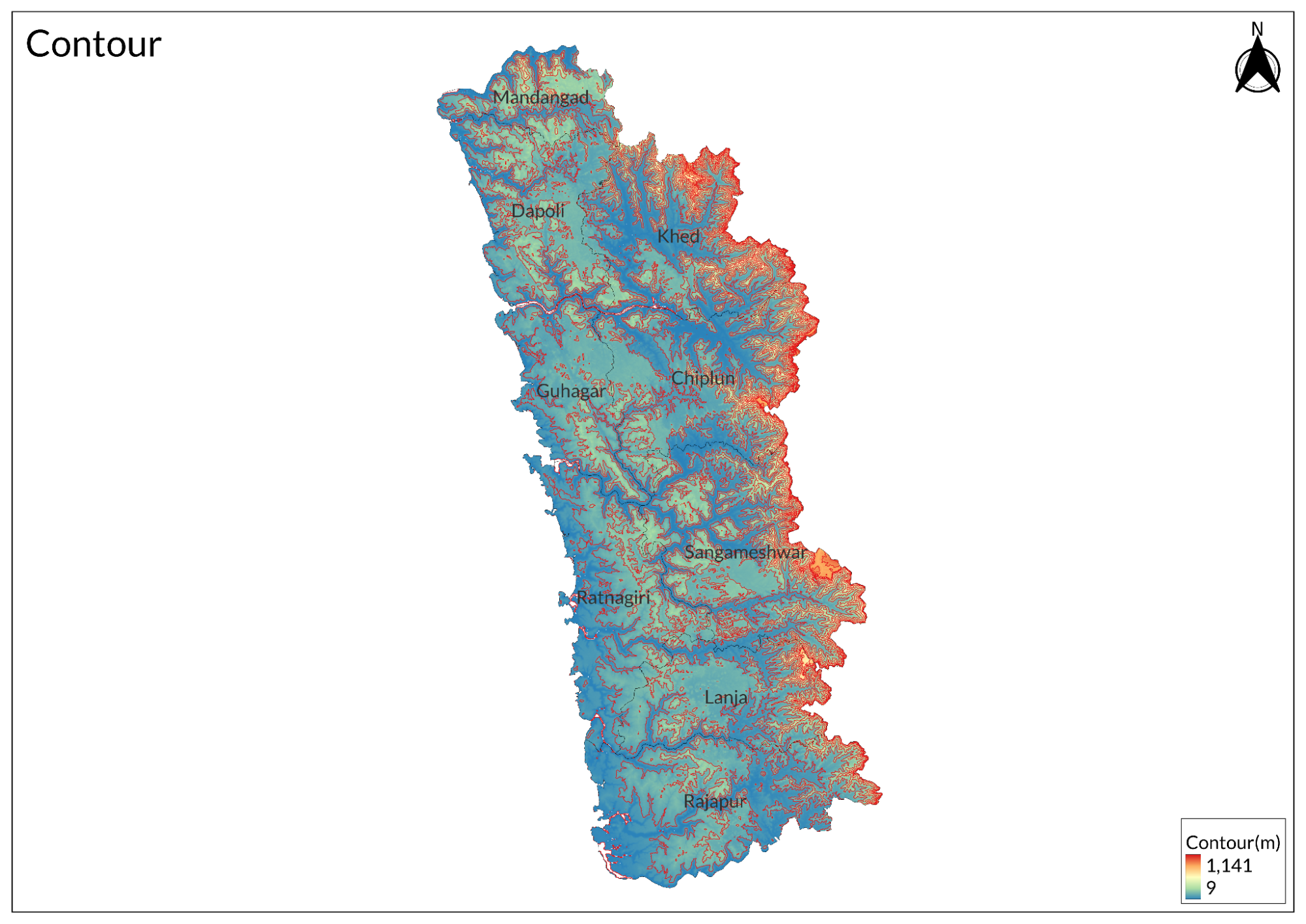

Physical Features

Ratnagiri district exhibits a distinctive three-tiered topographical layout that defines its landscape and influences its ecology. The easternmost section is dominated by the majestic Sahyadri Mountain range, which forms a natural boundary and plays a crucial role in the region's weather patterns. Moving westward, the terrain transitions into a zone of smaller hills, creating an undulating landscape that characterizes much of the district's interior. Finally, the westernmost section consists of coastal plains that gradually merge with the Arabian Sea, forming a diverse coastal ecosystem. However, the physical landscape of Ratnagiri has undergone significant changes due to human activities. Industrial development, particularly in areas like the Lote Parshuram Industrial area, Mirjole MIDC, and Kherdi MIDC, has modified the natural topography.

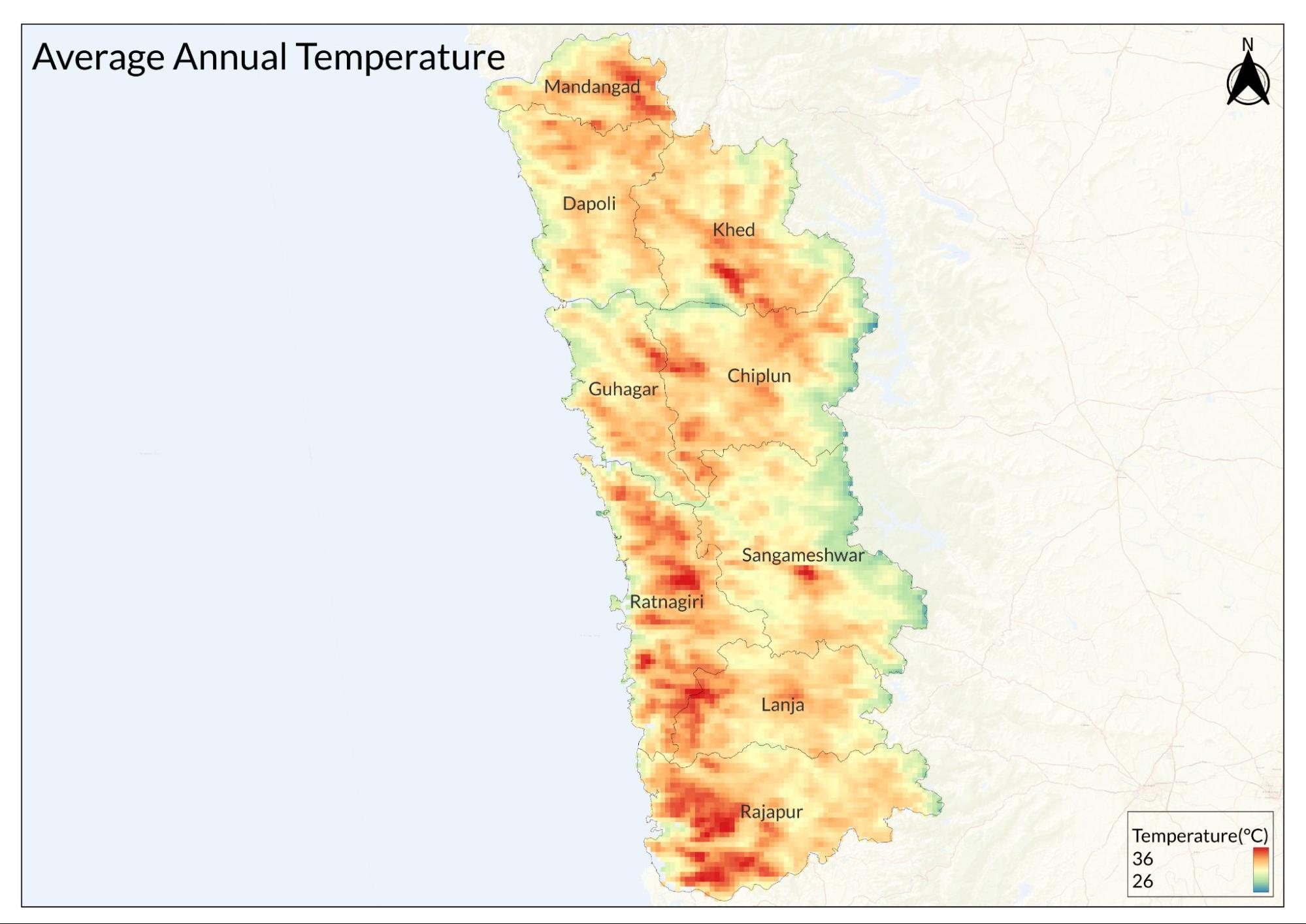

Climate

Ratnagiri experiences a distinct tropical monsoon climate characterized by two primary seasons: a wet season and a dry season. The climate is significantly influenced by its coastal location and topographical features, creating unique weather patterns throughout the year.

The temperature in Ratnagiri remains relatively moderate throughout the year, with a typical range between 72°F (22°C) and 91°F (33°C). This narrow temperature band makes it comfortable for habitation, though the high humidity levels can make it feel warmer than the actual temperature. Extreme temperatures are rare, with the mercury rarely dropping below 69°F (20.5°C) or rising above 95°F (35°C).

The wet season in Ratnagiri is characterized by warm temperatures, high humidity, and frequent rainfall. During this period, the weather becomes oppressive due to the combination of heat and humidity, while strong winds and overcast skies are common features. The monsoon brings significant precipitation, which is crucial for the region's agriculture and water resources.

In contrast, the dry season presents hot and muggy conditions but with predominantly clear skies. This period offers better visibility and more stable weather conditions, making it ideal for outdoor activities. The clearer skies during this season also result in higher daytime temperatures, though the coastal location helps moderate the heat. For tourists and visitors interested in beach activities or outdoor explorations, the period from late November to early April is considered optimal. During these months, the weather is more predictable, with lower humidity levels and minimal rainfall, making it perfect for various outdoor activities and sightseeing.

Geology

The district exhibits a clear three-zone geological structure that transitions from east to west. The eastern zone, dominated by the Sahyadri region, features massive basalt formations that create step-like terrain features. These formations, products of ancient volcanic activity, present exposed rock faces and steep cliffs that tell the story of the region's geological past. This zone contains significant deposits of black rock, which has become a valuable resource for modern construction activities.

Moving westward, the central hill region displays a different geological character, marked by weathered basalt formations that create an undulating landscape. This area has become particularly significant for human activity, housing numerous quarrying sites that provide essential construction materials. The rock here shows varying degrees of metamorphosis, creating diverse geological features that have both economic and environmental implications. The majority of the region's mining activities are concentrated in this central zone, highlighting its economic importance.

The coastal zone in the west presents yet another distinct geological profile, characterized by marine deposits and unique coastal formations. This area showcases the interesting interplay between marine geological processes and terrestrial rock formations. Notable features include wave-cut platforms and distinctive formations like Bamanghal near Guhahagar, where the interaction between sea and rock has created remarkable geological structures. The coastal zone also contains important alluvial deposits from river systems that have influenced local soil composition and fertility.

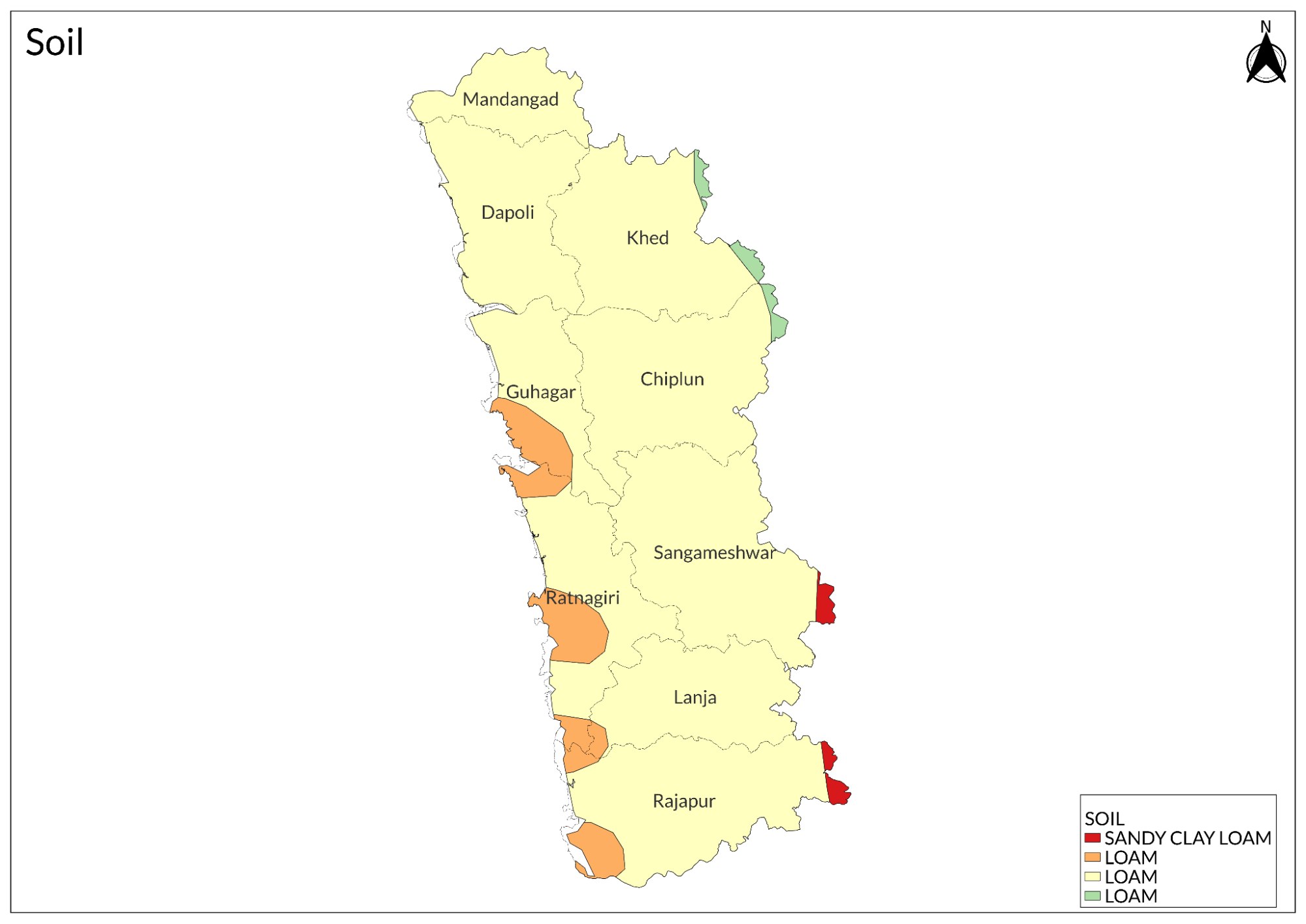

Soil

In the eastern Sahyadri region, lateritic soil predominates, characterized by its reddish color due to high iron oxide content. This soil type is typically well-drained and slightly acidic, making it particularly suitable for crops like cashew nuts and mangoes. The lateritic soils have developed through intensive weathering of the underlying basalt rock, resulting in a soil profile that's rich in iron and aluminum oxides but relatively poor in organic matter.

The central region features a transitional soil type that combines characteristics of both lateritic and coastal soils. These soils are generally moderately deep to deep and have better water retention capacity compared to the lateritic soils of the eastern zone. Their formation has been influenced by the weathering of basalt rocks and the accumulation of organic matter over time, creating fertile conditions for various agricultural activities.

Along the coastal plains, the soils are predominantly alluvial and sandy in nature. These soils have been formed through the deposition of materials by rivers and marine processes. While generally fertile, these coastal soils can have high salt content due to their proximity to the sea, requiring careful management for agricultural use. The texture varies from sandy to sandy loam, with good drainage but relatively poor water retention capacity.

The river valleys of Ratnagiri possess some of the most fertile soils in the district. These alluvial soils are enriched by regular deposits of sediments from the rivers and are characterized by high organic matter content. The Vashishti, Shastri, and other river valleys feature deep, well-structured soils that are ideal for intensive agriculture, particularly rice cultivation and horticultural crops.

Minerals

The mineral profile of Ratnagiri is primarily dominated by basalt, commonly known as black rock, which forms the fundamental geological structure of the region. This mineral resource has significant economic importance due to its extensive use in construction and infrastructure development.

Basalt mining in Ratnagiri has notably altered the landscape, particularly in the hilly regions. Local reports indicate that numerous smaller hills have been modified or partially excavated to facilitate mining operations. These quarrying activities have become an important part of the local economy while simultaneously raising environmental concerns.

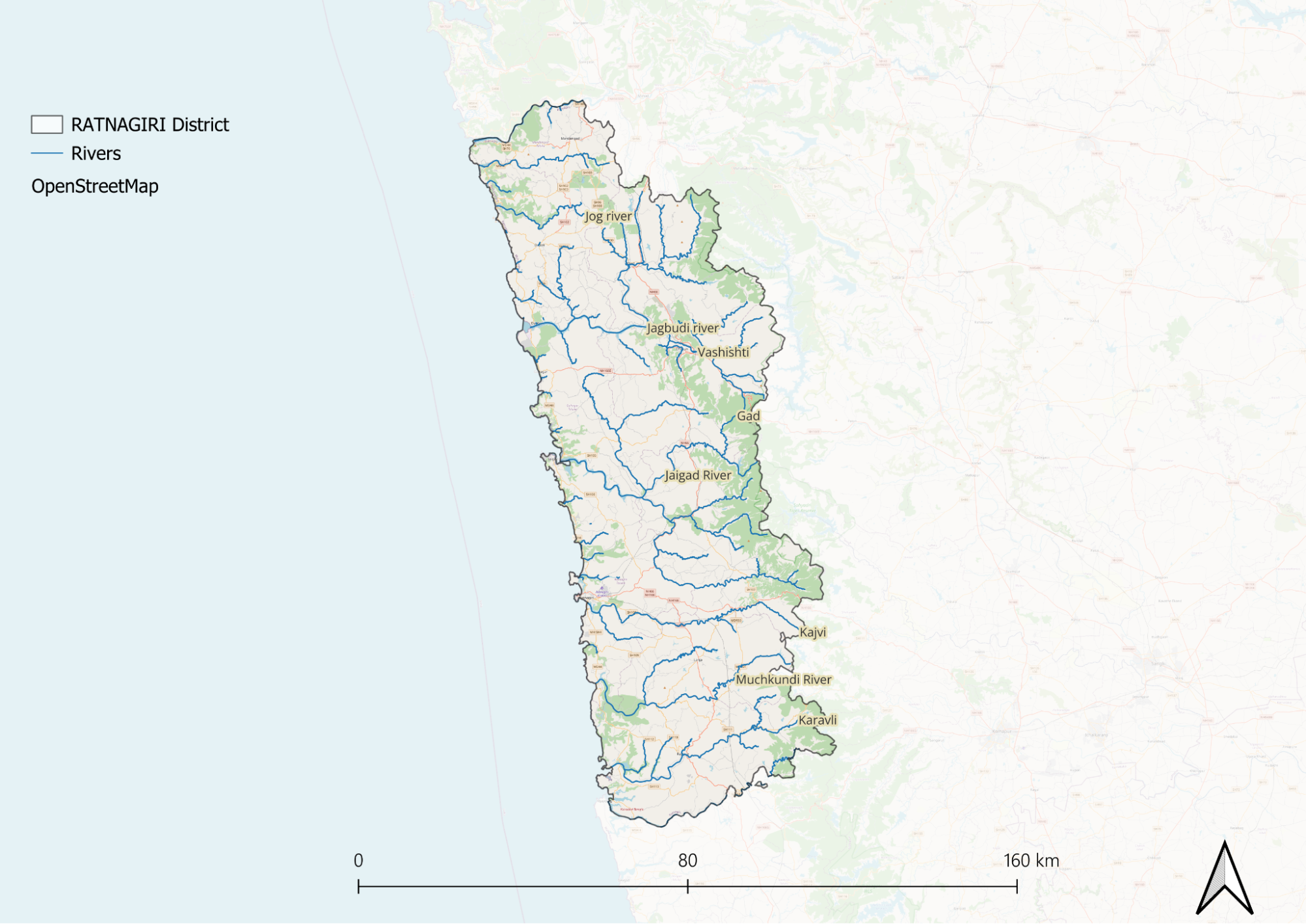

Rivers

Rivers flow from the Sahyadri Mountains to the Arabian Sea in Ratnagiri, forming a network that supports the region's ecology and economy. These rivers have shallow basins that widen near their confluences.

The Vashishti River stretches 68 kilometers within Ratnagiri's boundaries. Its tributaries include the Jagbudi, Baitarni, Tamdinadi, Dhavati Nadi, and Kaamaal Nala, along with smaller creeks like the Shiv. The Koyna Hydroelectric Project diverts additional water into the river, leading to floods in Chiplun City during monsoons. The Shashtri River extends 80 kilometers from the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve through Ratnagiri, Sangameshwar, and Guhagar. Unlike other rivers, it flows freely without dams. Major tributaries include the Asavi, Gadgadi, Bav, Gad, and Gandagi. The Sangameshwar-Shrigarpur communities depend on their waters, and their banks host 22 sacred groves.

The district includes other major rivers: the Jagbudi (meaning "river that can drown the world"), Jaigad, Muchkundi, and Jaitapur. Minor rivers and creeks include the Kajali, Ratnagiri, Bav, Gadnadi, Kelsi, Ada, Jog, Palshet, Borya, and Pavas. These waterways swell during monsoons and support local agriculture.

Industrial development threatens these river systems. The Lote Parshuram Industrial area has released effluents into the Vashishti River since the 1980s, affecting fishing near Dabhol. The Kherdi MIDC and Gane Khadpoli MIDC add to river pollution. The Jaigad Creek faces impacts from three projects: a thermal power plant, a port complex, and the SEZ development. Conservation efforts include the "Nadi Ki Pathshala" workshop by Jalbiradari Maharashtra and Chiplun Nagapalika, which studied the Vashishti, Jagbudi, Shiv, and Khore rivers. While most rivers maintain their flow, the challenge lies in balancing development with environmental protection.

Botany

The district hosts several common plants found throughout its territory, including Alphonso Mangoes, Phanas (Jackfruit), Kaju (Cashew Nut), Beetle Nut, Coconut, Bananas, Karvand (Forest Berries), Jambhol, Nilgiri, Teak, and Chinch. These plants form the backbone of local agriculture and forest ecosystems.

The region features several unique plant species, each with distinct characteristics and uses. The Kuda Flower, abundant in forested areas, is harvested and dried during the summer months. Once dried and brown, it's used to prepare bhaji, a dish eaten with rice flour Bhakri. The Tera plant's leaves are used in local cuisine, prepared as a soupy liquid with garlic and groundnuts, typically served with rice and rice flour Bhakri.

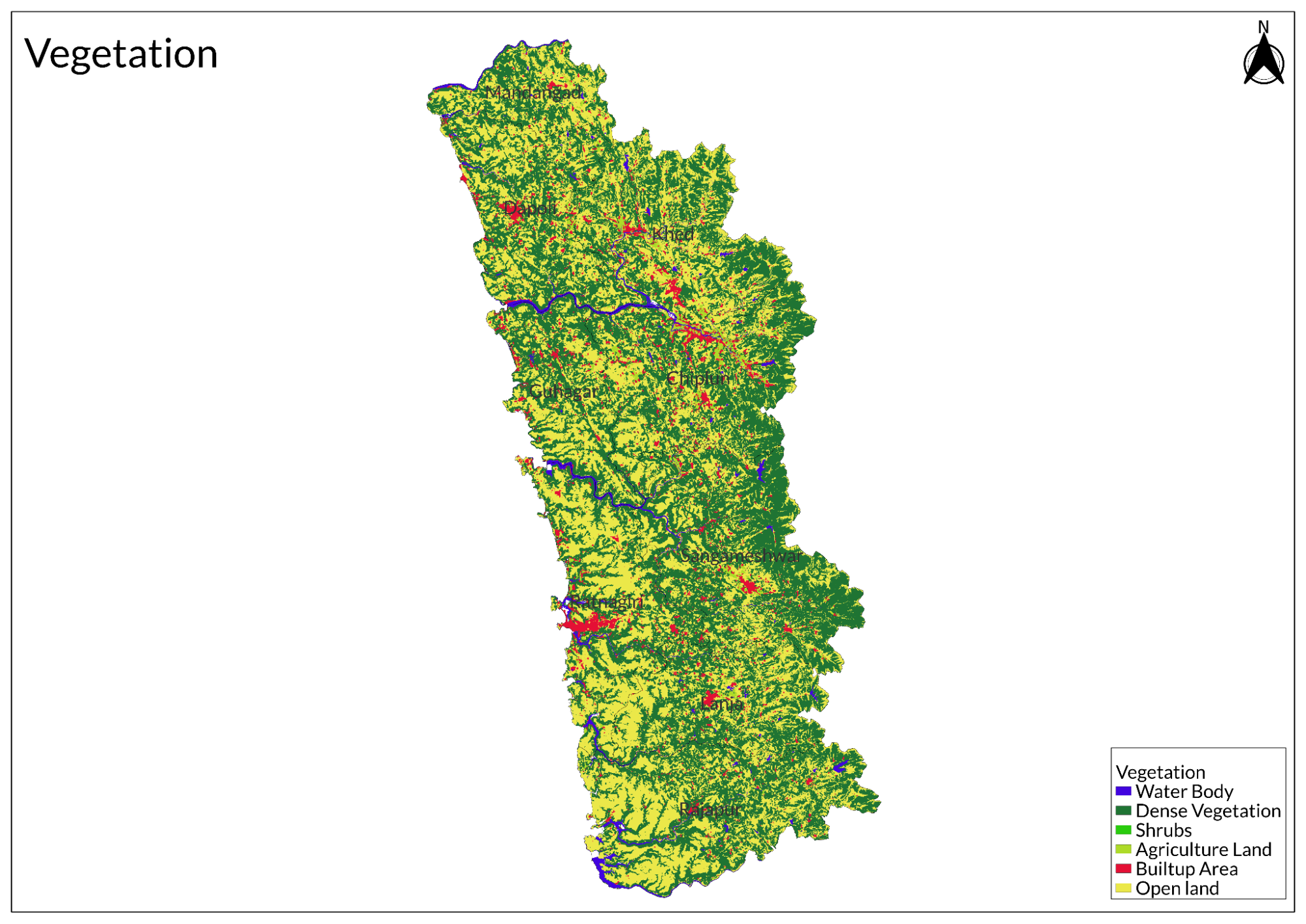

The district's forest cover remains relatively stable at 561 kha, though it faces certain challenges. Since 2001, the area has lost 25 ha of humid primary forests and 123 ha of overall tree cover. Environmental concerns include the introduction of non-native "show plants" that might affect endemic species, highlighting the need for balanced development and conservation approaches.

Medicinal plants form an important part of the local flora. Katar Ningdi's leaves are processed into an ointment for knee pain by crushing and roasting them. Ningdum, a spiky plant, provides natural burn relief through its white sap. These plants represent traditional medical knowledge that continues to serve local communities.

Wild Animals

The mammalian population includes macaques and langurs in forested areas, leopards in more remote regions, otters near water bodies, and squirrels throughout the district. These mammals have adapted to different ecological niches within the region's diverse terrain. The district's water bodies support unique aquatic life. Freshwater crocodiles inhabit the rivers, particularly the Vashishthi and Savitri. Crabs thrive in both saltwater and freshwater environments, contributing to local ecosystems and providing livelihood opportunities.

Crustaceans (Crabs)

Gubernatoriana thackerayi

Ghatiana thackerayi, named in honour of its discoverer, Tejas Thackeray, is a diurnal crab species known for its vibrant coloration and distinctive habitat preferences. It was discovered during the monsoon season among horizontal cracks in sloping rock formations in the Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra. Thackeray had originally proposed the name Gubernatoriana rubra (Latin for "red"), referencing the crab's vivid coloration, but the final naming choice was made by his collaborators.

This species is characterized by a striking red shell and walking legs, while its pincers (chelae) are a vivid orange-red, creating a visually arresting contrast. G. thackerayi is known to feed on worms, foraging actively during the day.

The pincers display notable sexual dimorphism. In males, the claws are slightly unequal in size, with the larger claw featuring spoon-shaped fingers that bear small, rounded teeth and a narrow gap between them. In females, both pincers are of equal size, lacking this asymmetry. Additionally, the long walking legs are lined with fine brown bristles, likely aiding in movement across the slippery, rain-soaked rocky terrain of its natural habitat.

G. thackerayi stands out for both its appearance and behavior, making it a remarkable addition to the freshwater crab diversity of the Western Ghats.

Forest Reserves

While Ratnagiri lacks government-declared wildlife sanctuaries, several private initiatives protect and showcase local wildlife. These include multiple bird-viewing sanctuaries and crocodile safaris. Notable locations include the Maldoli Crocodile Safari in Chiplun, Narvekar Bird Sanctuary, Moghe's Bird Sanctuary, and Nandu's Bird Sanctuary. These private sanctuaries play an important role in wildlife conservation and education. Conservation efforts are led by organizations like Sahyadri Nisarg Mitra, established in 1992. The organization focuses on protecting various species, including turtles, pangolins, and birds such as Indian swiftlets, Sea Eagles, and Vultures. A notable success story is the conservation of Olive Ridley turtles at Velas Beach, where protection efforts began in 2002. Similar conservation work continues at Anjarle, Dapoli, supported by local "Kasav Mitra Mandal" groups.

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Deforestation

Deforestation in Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra, has reached critical levels, with 526 hectares of natural forest lost in 2023 alone (generating 83.4 kilotons of CO₂ emissions) and 124 hectares of tree cover destroyed between 2001-2023 (adding 58.5 kilotons of CO₂); by 2010, tree cover represented a mere 2.9% of the district's land area with only 24.4 hectares remaining. The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel attributes this environmental crisis to mining operations, power projects, polluting industries, and illegal activities, all of which have caused significant ecological degradation and social consequences in the region.

Coastal Erosion

Coastal erosion in Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra, has become a critical environmental issue with 37% of the coastline designated as high-risk, particularly affecting villages like Velas and Bhankot, where shorelines are receding at an average rate of 1.27 meters annually and high tide levels have risen 5-6 centimeters since 1978. This erosion, intensified by rising sea levels, has caused saltwater intrusion into agricultural lands, converting farmlands into mangrove forests and devastating livelihoods of local farmers like Praful Manohar Mahadikar, who are forced to consider salt-tolerant crops as an adaptation strategy. Despite the construction of seawalls, erosion continues unabated, threatening local biodiversity including Olive Ridley turtle nesting sites, with experts cautioning that such physical barriers may simply relocate rather than solve the problem.

Water Scarcity

Water scarcity in Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra, is a growing concern influenced by various factors such as rainfall patterns, topography, industrial activities, and demographic changes. Although the region receives substantial rainfall during the monsoon season, this water is often not retained effectively. The hilly terrain and laterite rock formations facilitate rapid runoff, causing much of the rainwater to flow directly into the Arabian Sea. Consequently, the water table in certain areas declines at a rate of 0 to 0.20 meters per year. Industrial activities further complicate the water scarcity issue, as effluents from industries can contaminate groundwater sources. Additionally, the increasing population in Maharashtra heightens the demand for water resources, while rapid urbanization and industrialization contribute to this rising need.

Climate Change Vulnerability

The Ratnagiri district in Maharashtra, India, faces mounting climate change threats, with coastal erosion accelerated by high tide levels that have risen 5-6 centimeters since 1978, causing aggressive wave action that damages beaches, estuaries, and flatlands while contributing to coastal flooding. Rising sea levels further exacerbate these challenges as the sea advances inland through estuaries and streams, submerging private lands through a northerly encroachment pattern that threatens both agricultural activities and local ecosystems. The district's climate vulnerability was dramatically exposed during the December 2004 tsunami, which revealed the region's susceptibility to flooding hazards, while the additional risk of earthquakes compounds concerns about Ratnagiri's environmental fragility and long-term sustainability.

Mining

Mining operations in Ratnagiri have triggered serious environmental degradation, with the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel reporting that both Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg districts suffer extensively from mining activities, power projects, and polluting industries that contaminate air and groundwater, deplete fisheries, accelerate deforestation, cause siltation of water bodies, and destroy unique biodiversity. Illegal mining operations further compound these environmental challenges, with the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board identifying mining waste from excavation as a significant contributor to ecological damage, while prevalent sand and stone mining continues without comprehensive monitoring data. Recent proposals like the Nanar Bauxite Block have met with strong resistance from local communities who fear additional environmental destruction and negative impacts on land use, water resources, and traditional agricultural practices.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Jaitapur Power Plant

Since 2005, Ratnagiri district residents have opposed the planned Jaitapur nuclear power plant, which would become the world's largest with six reactors generating 9,900 megawatts. The project, situated in Seismic Zone III, faces resistance due to environmental and safety concerns, requiring land acquisition from five fishing villages: Madban, Varliwada, Karel, Niveli, and Mithgavane. Local fishermen, farmers, environmentalists, and marine biologists have raised objections about irregular land acquisition procedures, inadequate public consultation on environmental impact assessments, and potential radiation leaks and ecological damage.

While official environmental impact assessments claim no adverse effects on local ecosystems, independent studies by the Bombay Natural History Society warn the project could harm biodiversity within a 10-kilometer radius. The controversy has sparked violent confrontations, including clashes between police and protesters in January 2006 following land acquisition notifications, with the Maharashtra government invoking emergency provisions to bypass standard landowner objection rights, further intensifying community resistance.

Legal challenges have mounted against the project through public interest litigation in the Bombay High Court, contesting environmental clearances granted without proper nuclear safety and pollution assessments. Despite French President Emmanuel Macron's 2018 reaffirmation of commitment to advance the project during his India visit, persistent local opposition has caused significant delays, with residents particularly concerned about increased sea temperatures affecting marine life and their livelihoods, effectively stalling the project's progress.

RRPCL Protests

Residents of Nanar and Barsu-Solgaon in Ratnagiri district have waged a persistent campaign against the Ratnagiri Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited (RRPCL), a joint venture with Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company that threatens to displace farmers and fisherfolk from seventeen villages across Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg. First proposed in 2017 at Babulwadi village and revived by the Maharashtra government in 2022 with a new site in Barsu, the massive oil refinery has sparked environmental concerns and warnings from archaeologists about potential damage to ancient rock carvings at the site, despite promises that the facility would process 60 million metric tonnes of crude oil annually and create significant employment.

Following a 2018 protest that drew 15,000 residents to Rajiv Gandhi Maidan and temporarily halted the project, opposition has intensified with community members refusing to surrender their land and demanding complete cancellation of the refinery. The conflict has escalated to police intervention, resulting in approximately 150 protesters being detained and later released on bail amid reports of procedural irregularities during arrest, highlighting the broader struggle between industrial development interests and communities fighting to protect their livelihoods, environment, and cultural heritage.

Bauxite Mining Project

Villagers in Nanar, Ratnagiri, have mobilized against a bauxite mining project targeting 358 acres containing 10 million tonnes of reserves, with protests occurring both locally and through a supportive group meeting in Mumbai's Parel area ahead of the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board's scheduled August 29 public hearing. This marks the community's second major environmental battle following their successful opposition to a refinery project in 2017-18, with residents now confronting a 50-year mining rights agreement granted to a Goa-based company in September 2020 that threatens their sea-facing village of 12 hamlets populated by farmers and fisherfolk.

Resident Satyavan Palekar emphasized the eco-sensitive nature of the area where villagers cultivate mangoes, cashews, and jackfruits, warning that mining operations would release harmful chemicals and dust while worsening the existing groundwater crisis. The opposition has gained formal support through two gram panchayat resolutions against the bauxite mine, with a third resolution anticipated soon, while the Konkan Refinery Virodhi Sanghatana coordinates local resistance efforts. Protesters plan to approach Chief Minister Eknath Shinde to request the postponement of the public hearing and are preparing a unified opposition letter, as local leader Ashok Valam firmly states they will not allow the project to advance despite the MPCB regional officer's request for written public feedback within 30 days before the hearing in Rajapur.

Turtle Conservation Efforts

The Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra (SNM) organization has led turtle conservation efforts in Ratnagiri district since 2002, beginning in Velas village with the protection of Olive Ridley turtles that resulted in 50 protected nests and 2,734 released hatchlings in its first year, and has since expanded to cover 720 kilometers of Maharashtra's coastline across 36 beaches and 12 villages. Conservation activities include monitoring nesting sites, relocating eggs to artificial nests for protection from predators, and engaging local "Kasav Mitra" volunteers who patrol beaches day and night to safeguard nests by carefully moving eggs to specially created protective sites on the same beaches. The initiative has fostered significant community involvement through the annual Turtle Festival, established in 2006, which promotes conservation awareness while providing local villagers with additional income through eco-tourism opportunities centered around turtle conservation.

Environmental NGOs

In Ratnagiri district, several environmental NGOs are actively engaged in conservation efforts aimed at protecting wildlife, promoting sustainable practices, and raising environmental awareness. Here’s an overview of some key organizations and their initiatives:

Apna Van Trust

Apna Van Trust leads afforestation efforts with a focus on native species and natural resource management. The organization educates farmers about agroforestry and sustainable agricultural practices while creating community-led conservation initiatives aimed at protecting local flora and fauna.

Konkan Nisarg Manch

This organization emphasizes forest conservation and environmental awareness. It organizes afforestation programs and advocates for the planting of native tree species. Konkan Nisarg Manch also works to raise awareness about the ecological impacts of deforestation and unplanned development while engaging communities in preserving biodiversity hotspots throughout the region.

Mangrove Society of India (MSI)

MSI is dedicated to the conservation and restoration of mangrove ecosystems in Ratnagiri's coastal areas. The organization focuses on restoring degraded mangrove forests and educating local communities about their ecological importance. MSI collaborates with government bodies to promote sustainable management practices for coastal ecosystems.

Nisarga Mitra Ratnagiri

This NGO is involved in biodiversity protection and sustainable tourism initiatives. It conducts bird-watching camps and biodiversity surveys while promoting eco-friendly tourism practices in both coastal and forested areas. Nisarga Mitra Ratnagiri also raises awareness about pollution's impact on local ecosystems.

Ratnagiri Conservation Society

This society focuses on protecting marine and coastal ecosystems, advocating against unregulated fishing practices, and addressing pollution in coastal waters. It organizes clean-up drives and workshops on marine conservation to engage the community in protecting their environment.

Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra (SNM)

Founded in 1992, SNM focuses on wildlife conservation and marine biodiversity. The organization is particularly known for its efforts in the conservation of endangered species such as Olive Ridley turtles and Indian pangolins. SNM monitors and protects turtle nesting sites along the Konkan coast, having expanded its marine turtle conservation program to cover 720 kilometers of coastline since its inception. Additionally, SNM conducts environmental education programs and promotes eco-tourism initiatives to engage local communities in conservation efforts.

Western Ghats Ecology Experts

Dedicated to preserving the ecosystems of the Western Ghats, this group conducts ecological studies and biodiversity mapping in Ratnagiri’s forests. They advocate for sustainable development practices in ecologically sensitive areas while working to mitigate the impacts of deforestation and industrialization.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Developmental activities have ‘seriously impacted’ districts of Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg, says expert panel. 2012, January 7. Conservation India; The Hindu.https://www.conservationindia.org/news/devel…

Dighe, S. 2021, August 1. Encroachment on slopes, deforestation to blame for landslides in Maharashtra: Experts. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Jal Swaraj in Ratnagiri: A Journey from Despair to Hope. 2024, April 26. Mukul Madhav Foundation.https://www.mmpc.in/jal-swaraj-in-ratnagiri-…

Lopes, F. 2023, June 7. Against the sea: Rising sea levels in Ratnagiri turn farm lands into mangrove forests.https://www.indiaspend.com/indias-climate-ch…

Marine Turtle Conservation in Maharashtra (2002 to 2006). Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra.https://www.snmcpn.org/turtles/conservation-…

Parida, U. K. 2024, August 5. After kicking out refinery plan, Nanar opposes bauxite mining. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nav…

Patil, Ajit. 2022, November 24. Ratnagiri Refinery: People’s Resistance to Defend Land, Livelihood and Environment. Liberation.https://www.liberation.org.in/detail/ratnagi…

Protests against Ratnagiri refinery: Skeletons in the development closet. 2023, May 19. Ecologise.https://ecologise.in/2023/05/19/protests-aga…

Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, India: Deforestation Rates & Statistics. Global Forest Watch.https://www.globalforestwatch.org/country/IN…

Ratnagiri, MH, IN. iNaturalist.https://www.inaturalist.org/places/ratnagiri…

Richa Malhotra. 2016. Meet the Western Ghats’ Wonderful New Freshwater Crabs. Science The Wire.https://science.thewire.in/science/meet-the-…

Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra.https://www.snmcpn.org/

Sonar, N., Gupta, A., & Kujur, A. 2019, May. Fisherfolk, Activists Oppose Jaitapur Nuclear Plant Proposed in Seismic Zone in Maharashtra. Land Watch Conflict.https://www.landconflictwatch.org/conflicts/…

Srivastava, S., Gupta, A., & Kujur, A. 2023, May 26. Communities revive campaign against oil refinery in Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra | Ratnagiri, Maharashtra. Land Watch Conflict.https://www.landconflictwatch.org/conflicts/…

Sudhi, K. S. 2011, December 30. ‘Ratnagiri, Sindhudurg regions seriously impacted by mining, power projects’. The Hindu.https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and…

Tehzeeb, F. 2023, May 17. Ratnagiri Refinery: State repression on a peaceful movement. Centre for Financial Accountability.http://www.cenfa.org/ratnagiri-refinery-stat…

Velas Turtle Festival. (2025). Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra.https://snmcpn.org/turtle-festival/velas-tur…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.